Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Accounting Basics

Uploaded by

Wiraswasta Mandiri0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views9 pagesLuca Pacioli was the first to describe the system of debits and credits in journals and ledgers. The industrial revolution spurred the need for more advanced cost accounting systems. The first standardized test for accountants was given in 1896, and the first CPAs were licensed in 1896.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentLuca Pacioli was the first to describe the system of debits and credits in journals and ledgers. The industrial revolution spurred the need for more advanced cost accounting systems. The first standardized test for accountants was given in 1896, and the first CPAs were licensed in 1896.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views9 pagesAccounting Basics

Uploaded by

Wiraswasta MandiriLuca Pacioli was the first to describe the system of debits and credits in journals and ledgers. The industrial revolution spurred the need for more advanced cost accounting systems. The first standardized test for accountants was given in 1896, and the first CPAs were licensed in 1896.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

Accounting Basics: History Of Accounting

Filed Under Accounting Financial Theory, Financial Theory, Accounting

By Bob Schneider

The name that looms largest in early accounting

history is Luca Pacioli

1

, who in 1494 first

described the system of double-entry

bookkeeping used by Venetian merchants in his

Summa de Arithmetica, Geometria, Proportioni

et Proportionalita

2

. Of course, businesses and

governments had been recording business

information long before the Venetians. But it was

Pacioli who was the first to describe the system

of debits and credits in journals and ledgers that

is still the basis of today's accounting systems.

The industrial revolution spurred the need for

more advanced cost accounting systems, and the development of corporations created much larger

classes of external capital providers - shareowners and bondholders - who were not part of the firm's

management but had a vital interest in its results. The rising public status of accountants helped to

transform accounting into a profession, first in the United Kingdom and then in the United States. In

1887, thirty-one accountants joined together to create the American Association of Public Accountants.

The first standardized test for accountants was given a decade later, and the first CPAs were licensed in

1896.

The Great Depression led to the creation of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 1934.

Henceforth all publicly-traded companies had to file periodic reports with the Commission to be

certified by members of the accounting profession. The American Institute of Certified Public

Accountants (AICPA) and its predecessors had responsibility for setting accounting standards until 1973,

when the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) was established. The industry thrived in the late

1

Fra Luca Bartolomeo de Pacioli (sometimes Paccioli or Paciolo; 14451517) was an Italian mathematician,

Franciscan friar (biarawan ordo Fransiskan), collaborator with Leonardo da Vinci, and seminal contributor to the

field now known as accounting. He was also called Luca di Borgo after his birthplace, Borgo Sansepolcro, Tuscany.

2

Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalit (Venice 1494), a textbook for use in the schools

of Northern Italy. It was a synthesis of the mathematical knowledge of his time and contained the first printed

work on algebra written in the vernacular (i.e. the spoken language of the day). It is also notable for including the

first published description of the method of bookkeeping that Venetian merchants used during the Italian

Renaissance, known as the double-entry accounting system.The system he published included most of the

accounting cycle as we know it today. He described the use of journals and ledgers, and warned that a person

should not go to sleep at night until the debits equaled the credits. His ledger had accounts for assets (including

receivables and inventories), liabilities, capital, income, and expenses the account categories that are reported

on an organization's balance sheet and income statement, respectively. He demonstrated year-end closing entries

and proposed that a trial balance be used to prove a balanced ledger. He is widely considered the "Father of

Accounting". Also, his treatise touches on a wide range of related topics from accounting ethics to cost accounting.

He introduced the Rule of 72, using an approximation of 100*log 2 more than 100 years before Napier and Briggs :

<St-and.ac.uk A Napierian logarithm before Napier, John J O'Connor and Edmund F Robertson>

20th century, as the large accounting firms expanded their services beyond the traditional auditing

function to many forms of consulting.

The Enron scandals in 2001, however, had broad repercussions for the accounting industry. One of the

top firms, Arthur Andersen, went out of business and, under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, accountants faced

tougher restrictions on their consulting engagements. One of the paradoxes of the profession, however,

is that accounting scandals generate more work for accountants, and demand for their services

continued to boom throughout the early part of the 21st century. (For details on this and other scandals

see, The Biggest Stock Scams Of All Time.)

Next: Accounting Basics: Branches Of Accounting

http://www.investopedia.com/university/accounting/accounting1.asp

Accounting Basics: Branches Of Accounting

Filed Under Accounting Financial Theory, Financial Theory, Accounting

By Bob Schneider

Accounting can be divided into several areas of activity. These can certainly overlap and they are often

closely intertwined. But it's still useful to distinguish them, not least because accounting professionals

tend to organize themselves around these various specialties.

Financial Accounting

Financial accounting is the periodic reporting of a company's financial position and the results of

operations to external parties through financial statements, which ordinarily include the balance sheet

(statement of financial condition), income statement (the profit and loss statement, or P&L), and

statement of cash flows. A statement of changes in owners' equity is also often prepared. Financial

statements are relied upon by suppliers of capital - e.g., shareholders, bondholders and banks - as well

as customers, suppliers, government agencies and policymakers. (To learn more on this read, What You

Need To Know About Financial Statements.)

There's little use in issuing financial statements if each company makes up its own rules about what and

how to report. When preparing statements, American companies use U.S. Generally Accepted

Accounting Principles, or U.S. GAAP. The primary source of GAAP is the rules published by the FASB and

its predecessors; but GAAP also derives from the work done by the SEC and the AICPA, as well standard

industry practices. (For more on this see, What is the difference between the IAS and GAAP?)

Management Accounting

Where financial accounting focuses on external users, management accounting emphasizes the

preparation and analysis of accounting information within the organization. According to the Institute of

Management Accountants, it includes "designing and evaluating business processes, budgeting and

forecasting, implementing and monitoring internal controls, and analyzing, synthesizing and aggregating

informationto help drive economic value."

A primary concern of management accounting is the allocation of costs; indeed, much of what now is

considered management accounting used to be called cost accounting. Although a seemingly mundane

pursuit, how to measure cost is critical, difficult and controversial. In recent years, management

accountants have developed new approaches like activity-based costing (ABC) and target costing, but

they continue to debate how best to provide and use cost information for management decision-making.

Auditing

Auditing is the examination and verification of company accounts and the firm's system of internal

control. There is both external and internal auditing. External auditors are independent firms that

inspect the accounts of an entity and render an opinion on whether its statements conform to GAAP

and present fairly the financial position of the company and the results of operations. In the U.S., four

huge firms known as the Big Four - PricewaterhouseCoopers, Deloitte Touche Tomatsu, Ernst & Young,

and KPMG - dominate the auditing of large corporations and institutions. The group was traditionally

known as the Big Eight, contracted to a Big Five through mergers and was reduced to its present number

in 2002 with the meltdown of Arthur Andersen in the wake of the Enron scandals. (For further

information see, An Inside Look At Internal Auditors.)

The external auditor's primary obligation is to users of financial statements outside the organization.

The internal auditor's primary responsibility is to company management. According to the Institute of

Internal Auditors (IIA), the internal auditor evaluates the risks the organization faces with respect to

governance, operations and information systems. Its mandate is to ensure (a) effective and efficient

operations; (b) the reliability and integrity of financial and operational information; (c) safeguarding of

assets; and (d) compliance with laws, regulations and contracts.

Tax Accounting

Financial accounting is determined by rules that seek to best portray the financial position and results of

an entity. Tax accounting, in contrast, is based on laws enacted through a highly political legislative

process. In the U.S., tax accounting involves the application of Internal Revenue Service rules at the

Federal level and state and city law for the payment of taxes at the local level. Tax accountants help

entities minimize their tax payments. Within the corporation, they will also assist financial accountants

with determining the accounting for income taxes for financial reporting purposes.

Fund Accounting

Fund accountingis used for nonprofit entities, including governments and not-for-profit corporations.

Rather than seek to make a profit, governments and nonprofits deploy resources to achieve objectives.

It is standard practice to distinguish between a general fund and special purpose funds. The general

fund is used for day-to-day operations, like paying employees or buying supplies. Special funds are

established for specific activities, like building a new wing of a hospital.

Segregating resources this way helps the nonprofit maintain control of its resources and measure its

success in achieving its various missions.

The accounting rules for federal agencies are determined by the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory

Board, while at the state and local level the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) has

authority.

Forensic Accounting

Finally, forensic accounting is the use of accounting in legal matters, including litigation support,

investigation and dispute resolution. There are many kinds of forensic accounting engagements:

bankruptcy, matrimonial divorce, falsifications and manipulations of accounts or inventories, and so

forth. Forensic accountants give investigate and analyze financial evidence, give expert testimony in

court and quantify damages.

Next: Accounting Basics: The Basics

The Difference Between Accounting and Bookkeeping

Bookkeeping is an unglamorous but essential part of accounting. It is the recording of all the economic

activity of an organization - sales made, bills paid, capital received - as individual transactions and

summarizing them periodically (annually, quarterly, even daily). Except in the smallest organizations,

these transactions are now recorded electronically; but before computers they were recorded in actual

books, thus bookkeeping.

The accountants design the accounting systems the bookkeepers use. They establish the internal

controls to protect resources, apply the principles of standards-setting organizations to the accounting

records and prepare the financial statements, management reports and tax returns based on that data.

The auditors that verify the accounting records and express an opinion on financial statements are also

accountants, as are management, tax and forensic accounting specialists. (To learn more see,

Accounting Not Just For Nerds Anymore.)

Double-Entry Bookkeeping

The economic events of a business are recorded as transactions and applied to the accounts (hence

accounting). For example, the cash account tracks the amount of cash on hand; the sales account

records sales made. The chart of accounts of even small companies has hundreds of accounts; large

companies have thousands.

The transactions are posted in journals, which were (and for some small organizations, still are) actual

books; nowadays, of course, the journals are typically part of the accounting software. Each transaction

includes the date, the amount and a description.

For example, suppose you have a stationery store. On April 19, a saleswoman for an antiques company

visits you, and you buy a lamp for your office for $250. A journal entry to record the transaction as a

debit to the Office Furniture account and a $250 credit to Accounts Payable could be written as follows

(Dr. is the abbreviation for debit, while Cr. is for credit):

Date

Account

Dr.

Cr.

April 19

Office Furniture

250

Accounts Payable

250

(Bought antique lamp; voucher #0016)

Each accounting transaction affects a minimum of two accounts, and there must be at least one debit

and one credit.

Keeping Good Accounting Records

Even a seemingly simple transaction like this one raises a host of accounting issues.

Date:Suppose you had already agreed by phone to buy the lamp on April 15, but the paperwork wasn't

done until April 19. And the lamp wasn't delivered on the 19th, but the 23rd. Or even as you bought it,

you were thinking that you didn't like it that much, and there's a strong chance you'll return it by the

30th, when the sale becomes final. On which date - 15th, 19th, 23rd, or 30th - did an economic event

occur for which a transaction should be recorded?

Amount:The sales price is $250, but you get a 10% discount (to $225) if you pay in 30 days; business is

bad, though, so you may need the full 90 days to pay. Similarly, however, you know the antique business

is also lousy; even though you agreed to pay $250, you can probably chisel another $50 off the price if

you threaten to return it. On the other hand, being in the stationery business, you know one of your

customers has been looking for a lamp like that for a long time; he told you in February he'd pay $300

for one.

So what amounts should you record on April 19 (if indeed you record a transaction on that date)? $250

or $225 or $200 or $300?

Accounts:You've debited the Office Furniture account. But actually you buy and sell antiques frequently

to your customers, and you're always ready to sell the lamp if you get a good offer. Instead of an Office

Furniture account used for fixed assets, should the lamp be recorded in a Purchases account you use for

inventory? And if this was a big company, there might be dozens of office furniture sub-accounts to

choose from.

Accountants rely on various resources to answer such questions. There are basic, time-honored

accounting conventions: standards set forth by various rules-making bodies, long-standing industry

practices and, most important, their own judgment honed through years of experience.

But the important point is that even the most basic accounting questions - when did an economic event

take place? What is the value of the transaction? Which accounts are affected by the transaction? - can

get very complex and the right answers prove very elusive. There's no excuse for out-and-out

misrepresentation of company results and sloppy auditing that certainly occurs. But the seeming

precision of financial statements, no matter how conscientiously prepared, is belied by the uncertainty

and ambiguity of the business activities they seek to represent.

Debits and Credits

We're accustomed to thinking of a "credit" as something "good" - our account is credited when we get a

refund; you get "extra credit" for being polite. Meanwhile, a "debit" is something negative - a debit

reduces our bank balance; it's used to mean shortcoming or disadvantage.

In accounting, debit means one thing: left-hand side. Credit means one thing: right-hand side. When you

receive cash - a "good" thing - you increase the Cash account by debiting it. When you use cash - a "bad"

thing - you decrease Cash by crediting it. On the other hand, when you make a sale, which is nice, you

credit the Sales account; when someone returns what you sold, which is not nice, you debit sales.

"Good" and "bad" have nothing to do with debit and credit.

Debit = Left; Credit = Right. That's it. Period.

Accrual vs. Cash Basis Accounting

As we've seen, deciding when an economic event occurs and an accounting transaction should be

recorded is a matter of judgment. Accrual accounting looks to the economic reality of the business,

rather than the actual inflows and outflows of cash. (For more on this see, The Essentials of Cash Flow.)

Although cash basis statements are simpler and make good sense for many individual taxpayers and

small businesses, it results in misleading financial statements. Consider a Halloween costume maker: it

conceives, produces and sells costumes throughout the year, but gets paid for its costumes mostly in

October. If sales were recognized only when cash was received, October would show an enormous

profit while all other months would show losses. Accrual accounting seeks to match the revenues

earned during a period with the expenses incurred to generate them, regardless of when cash comes in

or goes out. (For details see, When should a company recognize revenues?)

Next: Accounting Basics: The Accounting Process

The Difference Between Accounting and Bookkeeping

Bookkeeping is an unglamorous but essential part of accounting. It is the recording of all

the economic activity of an organization - sales made, bills paid, capital received - as

individual transactions and summarizing them periodically (annually, quarterly, even daily).

Except in the smallest organizations, these transactions are now recorded electronically; but

before computers they were recorded in actual books, thus bookkeeping.

The accountants design the accounting systems the bookkeepers use. They establish

the internal controls to protect resources, apply the principles of standards-setting

organizations to the accounting records and prepare the financial statements, management

reports and tax returns based on that data. The auditors that verify the accounting records

and express an opinion on financial statements are also accountants, as are management,

tax and forensic accounting specialists. (To learn more see, Accounting Not Just For Nerds

Anymore.)

Double-Entry Bookkeeping

The economic events of a business are recorded as transactions and applied to the accounts

(henceaccounting). For example, the cash account tracks the amount of cash on hand; the

sales account records sales made. The chart of accounts of even small companies has

hundreds of accounts; large companies have thousands.

The transactions are posted in journals, which were (and for some small organizations, still

are) actual books; nowadays, of course, the journals are typically part of the accounting

software. Each transaction includes the date, the amount and a description.

For example, suppose you have a stationery store. On April 19, a saleswoman for an

antiques company visits you, and you buy a lamp for your office for $250. A journal entry to

record the transaction as a debit to the Office Furniture account and a

$250 credit to Accounts Payable could be written as follows (Dr. is the abbreviation for debit,

while Cr. is for credit):

Date

Account

Dr.

Cr.

April 19

Office

Furniture

250

Accounts

Payable

250

(Bought antique lamp; voucher #0016)

Each accounting transaction affects a minimum of two accounts, and there must be at least

one debit and one credit.

Keeping Good Accounting Records

Even a seemingly simple transaction like this one raises a host of accounting issues.

Date:Suppose you had already agreed by phone to buy the lamp on April 15, but the

paperwork wasn't done until April 19. And the lamp wasn't delivered on the 19th, but the

23rd. Or even as you bought it, you were thinking that you didn't like it that much, and

there's a strong chance you'll return it by the 30th, when the sale becomes final. On which

date - 15th, 19th, 23rd, or 30th - did an economic event occur for which a transaction

should be recorded?

Amount:The sales price is $250, but you get a 10% discount (to $225) if you pay in 30 days;

business is bad, though, so you may need the full 90 days to pay. Similarly, however, you

know the antique business is also lousy; even though you agreed to pay $250, you can

probably chisel another $50 off the price if you threaten to return it. On the other hand,

being in the stationery business, you know one of your customers has been looking for a

lamp like that for a long time; he told you in February he'd pay $300 for one.

So what amounts should you record on April 19 (if indeed you record a transaction on that

date)? $250 or $225 or $200 or $300?

Accounts:You've debited the Office Furniture account. But actually you buy and sell antiques

frequently to your customers, and you're always ready to sell the lamp if you get a good

offer. Instead of an Office Furniture account used for fixed assets, should the lamp be

recorded in a Purchases account you use for inventory? And if this was a big company,

there might be dozens of office furniture sub-accounts to choose from.

Accountants rely on various resources to answer such questions. There are basic, time-

honored accounting conventions: standards set forth by various rules-making bodies, long-

standing industry practices and, most important, their own judgment honed through years

of experience.

But the important point is that even the most basic accounting questions - when did an

economic event take place? What is the value of the transaction? Which accounts are

affected by the transaction? - can get very complex and the right answers prove very

elusive. There's no excuse for out-and-out misrepresentation of company results and

sloppy auditing that certainly occurs. But the seeming precision of financial statements, no

matter how conscientiously prepared, is belied by the uncertainty and ambiguity of the

business activities they seek to represent.

Debits and Credits

We're accustomed to thinking of a "credit" as something "good" - our account is credited

when we get a refund; you get "extra credit" for being polite. Meanwhile, a "debit" is

something negative - a debit reduces our bank balance; it's used to mean shortcoming or

disadvantage.

In accounting, debit means one thing: left-hand side. Credit means one thing: right-hand

side. When you receive cash - a "good" thing - you increase the Cash account by debiting it.

When you use cash - a "bad" thing - you decrease Cash by crediting it. On the other hand,

when you make a sale, which is nice, you credit the Sales account; when someone returns

what you sold, which is not nice, you debit sales.

"Good" and "bad" have nothing to do with debit and credit.

Debit = Left; Credit = Right. That's it. Period.

Accrual vs. Cash Basis Accounting

As we've seen, deciding when an economic event occurs and an accounting transaction

should be recorded is a matter of judgment. Accrual accounting looks to the economic

reality of the business, rather than the actual inflows and outflows of cash. (For more on

this see, The Essentials of Cash Flow.)

Although cash basis statements are simpler and make good sense for many individual

taxpayers and small businesses, it results in misleading financial statements. Consider a

Halloween costume maker: it conceives, produces and sells costumes throughout the year,

but gets paid for its costumes mostly in October. If sales were recognized only when cash

was received, October would show an enormous profit while all other months would show

losses. Accrual accounting seeks to match the revenuesearned during a period with

the expenses incurred to generate them, regardless of when cash comes in or goes out.

(For details see, When should a company recognize revenues?)

Next: Accounting Basics: The Accounting Process

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- FS For Independent MovieDocument59 pagesFS For Independent MovieWiraswasta Mandiri100% (2)

- Cebu Branch Submitted The Following Data To Its Home Office in Manila For 2016, Its First Year of OperationDocument31 pagesCebu Branch Submitted The Following Data To Its Home Office in Manila For 2016, Its First Year of OperationPappy Tres100% (1)

- 1 - Cost Accounting As A Base-1 PDFDocument7 pages1 - Cost Accounting As A Base-1 PDFWiraswasta MandiriNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Financial EvaluationDocument16 pagesChapter 7 Financial EvaluationMersha KassayeNo ratings yet

- Optimize Your Sales Approach with Jill Konrath's SNAP Selling SummaryDocument16 pagesOptimize Your Sales Approach with Jill Konrath's SNAP Selling SummaryrraiprraiNo ratings yet

- Hospital Supply Inc Cost AnalysisDocument5 pagesHospital Supply Inc Cost AnalysisMEERA JOSHY 192743633% (3)

- Supply Chain Finance Jul17Document4 pagesSupply Chain Finance Jul17Satrio YuliawanNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Shoe IndustryDocument14 pagesPakistan Shoe IndustryShaheen_8392% (13)

- Cost Accounting 14th Ed - CARTER - 11 - 50Document58 pagesCost Accounting 14th Ed - CARTER - 11 - 50Wiraswasta MandiriNo ratings yet

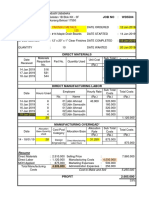

- COST SHEET Atau JOB COSTDocument1 pageCOST SHEET Atau JOB COSTWiraswasta MandiriNo ratings yet

- Airline Financial Statements - Chapter 2Document1 pageAirline Financial Statements - Chapter 2Wiraswasta MandiriNo ratings yet

- Catalytic Chlorine Dioxide - How It Is WorkDocument2 pagesCatalytic Chlorine Dioxide - How It Is WorkWiraswasta MandiriNo ratings yet

- Ne-AkdDocument193 pagesNe-AkdWiraswasta Mandiri100% (1)

- Modul SIMRS Versi Tally ERPDocument1 pageModul SIMRS Versi Tally ERPWiraswasta MandiriNo ratings yet

- Shreya Sarwade - 23-1632Document23 pagesShreya Sarwade - 23-1632beharenbNo ratings yet

- Slca Questions PDFDocument3 pagesSlca Questions PDFamna zamanNo ratings yet

- Revlon 1Document13 pagesRevlon 1rofiatusNo ratings yet

- IJCRT2207378Document7 pagesIJCRT2207378Khushi PatelNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Agreement and ContractDocument4 pagesDifference Between Agreement and ContracthkaqlqNo ratings yet

- ENVIRONMENTAL ANALYSIS: OPPORTUNITIES & THREATSDocument31 pagesENVIRONMENTAL ANALYSIS: OPPORTUNITIES & THREATSSparsh SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Transfer PricingDocument6 pagesTransfer Pricingrpulgam09No ratings yet

- Malaysia RD020 Requirement GST 20150112 V1 0Document20 pagesMalaysia RD020 Requirement GST 20150112 V1 0Venkata RamanaNo ratings yet

- Market Plan and Control: Submitted To: Prof. Ajay BansalDocument28 pagesMarket Plan and Control: Submitted To: Prof. Ajay BansalAkhil ThakurNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 SDocument24 pagesLecture 1 SMarie SarangayaNo ratings yet

- Laundry Business Plan for North Campus, New DelhiDocument42 pagesLaundry Business Plan for North Campus, New DelhiAkshat MehrotraNo ratings yet

- Profit Prior To IncorporationDocument4 pagesProfit Prior To Incorporationgourav mishraNo ratings yet

- Tax Invoice TitleDocument1 pageTax Invoice TitleVamshi KrishnaNo ratings yet

- CVP Analysis Helps Rongdhonu Company Estimate Profit Impact of Sales IncreaseDocument1 pageCVP Analysis Helps Rongdhonu Company Estimate Profit Impact of Sales IncreaseA.K.M. Rubyat Hasan ApuNo ratings yet

- Pricing Methods ExplainedDocument12 pagesPricing Methods ExplainedSonali KapoorNo ratings yet

- Acc 101 Final Exam PrintDocument11 pagesAcc 101 Final Exam Printchristian garciaNo ratings yet

- Retail Franchising: The Word "Franchise" Is of Anglo-French Derivation - From Franc, Meaning FreeDocument17 pagesRetail Franchising: The Word "Franchise" Is of Anglo-French Derivation - From Franc, Meaning Freeprabhatrc4235No ratings yet

- L&T Infotech: Strong Operational PerformanceDocument12 pagesL&T Infotech: Strong Operational Performanceashok yadavNo ratings yet

- Case General Dollar Solution Abdul Majeed MBA-CS 3Document5 pagesCase General Dollar Solution Abdul Majeed MBA-CS 3Sufi MajeedNo ratings yet

- Strategies in Action: 13 Options for Growth and StabilityDocument66 pagesStrategies in Action: 13 Options for Growth and StabilitySemira muradNo ratings yet

- 8 VatDocument11 pages8 VatRiyo Mae MagnoNo ratings yet

- Centor Escolar University Financial Accounting and Reporting Quiz 2Document6 pagesCentor Escolar University Financial Accounting and Reporting Quiz 2Beverly Velasco0% (1)

- 4.2 Costs-Scale-of-Production-and-Break-Even-Analysis - HandoutDocument16 pages4.2 Costs-Scale-of-Production-and-Break-Even-Analysis - Handoutdenny_sitorusNo ratings yet

- Gujarat Value Added Tax ActDocument7 pagesGujarat Value Added Tax ActvikrantkapadiaNo ratings yet

- Financial Report on Project C During COVID-19Document8 pagesFinancial Report on Project C During COVID-19YENG KABIGTINGNo ratings yet