Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kenny's Criminal Law

Uploaded by

inpbm06330Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kenny's Criminal Law

Uploaded by

inpbm06330Copyright:

Available Formats

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .

>>>>> P

a

g

e

1

KENNY'S

CRIMINAL LAW

. KENNY'S CRIMINAL LAW (CHAPTERS 1 TO 5)

[Refers to English criminal Law]

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

2

CHAPTER-1 CRIME AND

CRIMINAL LAW

1. The nature of a crime:

Difficulty of definition. Tort and crime. Crime in the primitive state.

Early Rome. Crimes as the creation of government policy.

2. The place of criminal law in criminal Science, Criminology, Criminal

policy, Criminal law.

CHAPTER-2

PRINCIPLES OF CRIMINAL LIABILITY

1. At common law :

A. Historical ; not embodied in a code. The period of strict liability.

Expiation of guilt by money payment. The most serious offences

recognized first. The need for a new test of criminal liability. The recognition

of a mental element in criminal liability.

B. actus reus (a) Deed of commission, a result of active conduct (b)

Result of omission.

Causation : (i) Where there is no physical participation (ii) Where the

participation is indirect (iii) Where any other person has intervened (iv)

Where the victim's own conduct has affected the result (v) contributory

negligence of the victim (vi) Where the participation is superfluous.

C. Mens rea (a) The objective standard of morality (b) The

emergence of a subjective standard Mala in se and Mala prohibita.

Voluntary conduct. Foresight of the consequences. Intention, reck-

lessness and negligence.

Where the consequences are different from those foreseen, Mens rea

alone not enough.

Vicarious liability at common law.

General principles of liability at common law, conclusions.

2. In Statutory Offences:

A. Actus reus in statutory offences:

B. Mens rea in statutory offences. Foresight of consequences

in statutory offences. Negligence in statutory offences. Vicarious liability in

statutory offences.

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

3

Mens rea as affecting the measure of punishment. Conclusions.

CHAPTER-3

VARIATION IN LIABILITY

1. Introduction

2. Mistake-Mistake as a defence at common law. Mistake as a defense

in statutory offences.

3. Intoxication

Intoxication relevant in establishing mistake, lack of intent, etc.

4. Compulsion - Obedience to order. Marital coercion. Duress per

minas. Necessity.

5'. Legally "abnormal persons, (a) The sovereign (b) Corporations (c)

Infants (d) Insane persons (e) Clerks in holy orders. Benefit of clergy.

CHA PTER-4 PRELIMARY CRIMES

1. introductory

2 Incitement

3 Criminal conspiracy

4 Attempt - History of the crime of attempt.

Elements of liability in attempt.

Actus reus in attempt. Attempts to do that which is

impossible. Merger of attempt when the crime intended is completed.

CHAPTER-5

THE POSSIBLE PARTIES TO A CRIME

1 Introductory

2 Principals in the first degree

3 Principals in the second degree : aiders

and abaters

4 Accessories before the fact

5 Accessories after the fact

6 Accomplices

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

4

*******************************************

Questions Bank

KENNY'S CRIMINAL LAW

1. Explain with what restraints Kenny attempt at defining

"Crime"'

2. Discuss the role of 'mens rea' in common law and in statutory

offences. Refer to leading cases. What is the position under I.P.C.?

3. Discuss how far

i) Mistake

ii) Intoxication and

iii) Insanity could be considered as defences

4. Explain how Kenny deals with "Attempt" in crimes. Refer to

Indian law.

5. Explain Kenny's concept of

1) Principals in the I & II degree

2) Accessories before the fact and accessories after the fact.

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

5

KENNY'S CRIMINAL LAW

CHAPTER 1

DEFINITION OF CRIMES

The definition of crime has always been regarded as a matter of

great difficulty. No satisfactory definition has been achieved as

yet in English law.

Tort and crime are a viscous inter-mixture. There is not much

difference between them. A crime is against the society and a

tort is against an individual. But, the society is composed of

individuals. The difference is one of degree.

'Felony' indicated something cruel, fierce or wicked The word

"Crime" was used in the 14th century. Any conduct which was

destructive according to a powerful section of any community

was a crime. The sovereign power of the state would command

to punish such crimes. The procedures taken by the courts, was

the "criminal proceeding".

In Rome, the sovereign power was with the senate. In the first

stage, there was no police organisation. It was left to the

individuals to punish: for example a traitor could be killed by

any person and there was no punishment to him.

Emperor Cladius, changed the marriage law as so to enable

him to marry his brother's daughter Agrippina. This is an

extreme case, but. a 'dictator could alter the law according to

his whimsies and fancies.

In later years, the law making, came under the influence of

public opinion.

Crime, is the creation of Govt. policy, according to Kenny.

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

6

Crimes, originate in the Govt. policy of the moment. The

governing power in society, forbids a man from doing certain

acts, called crimes. Of course, subsequent governments may

change them. As long as this changing pattern continues, the

nature of crime, eludes a true definition. However, according to

Kenny, there are three characteristics in a crime.

i) It is a harm caused by human conduct, which the sovereign

desires to prevent.

ii) The preventive measure is threat of punishment.

iii) Legal procedures are employed to prove the guilt

according to law.

CHAPTER -2

PRINCIPLES OF CRIMINAL LIABILITY

Much of English criminal law is not contained in any code (in

India there is the l.P.C.) hut it is a conglomerate mass of

rules based on common law, and in addition there are a few

enactments made by Parliament from time to time.

It was Chief J ustice Coke who stated the rule "Actus non

facit reum nisi mens sit rea" (the act and the intent must

both concur to constitute crime). This famous maxim refers

to man's deed (actus) and his mental processes (mens) at the

time of the commission of the offense. This means the

conduct of the person must have been inspired and actuated

by his mens rea.

In Meli and others V.R.. the facts were, that M and others

took D to a hut at night, gave him beer, and, beat him on his

head with intent to kill him. Thinking him to be dead, they

carried the body out and rolled it down a hill. Medical

evidence showed, that death was due to exposure to the cold

as he was lying unconscious, and not due to the beating.

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

7

Defense was as follows : The first part was the beating with

intent to kill M ; but, this beating did not cause the death,

hence, there was no actus reus of murder. Once, they

believed that he was dead, their intention to kill had ceased ;

but, they desired to evade detection (malice afore thought)

and hence, put him down the hill. Here, death was due to

freezing, but, the Privy Council rejected this and held that it

was one transaction and therefore, it was murder.

Actus reus :

This is the deed or the commission. It is the material result of

the conduct of the accused, which the law wants to prevent. In

case of murder, it is the victim's -death by any means that is the

actus reus, but mens rea is the intention of the accused.

The actus reus must have been prohibited to create criminal

liability e.g.. harmto the person, destruction of property etc. It

is therefore, clear that if killing is authorised e.g. death

sentence, there is no murder.

Causation : A man is said to have caused, the actus reus of

killing a person, if death would not have occurred without the

participation of the accused.

(i) This participation may be direct i.e., when the accused A

kills B

(ii) It is indirect when he instigates another to kill. A secretly

puts poison into a drink which A knows that B will offer to C.

(iii) A crime may be committed without physical participation

e.g. conspiracy, abetement etc.

(iv) Mens rea in one and actus reus in another is possible. A

keeps a goldsmith G, at the point of gun, takes him to a house

where G is forced to open the lock which he does. A thereupon

takes away the goods, here, G is kept in such a threat to his life

that there is no 'mens rea' and hence not guilty.

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

8

v) By intervention of a third person, a crime may be committed.

!n R.C. Higgins, the warden of a jail was held not guilty for the

death of the prisoner. The prisoner had been confined for 44

days in a dangerous room. The warden neither intended nor did

he know about the confinement. But. such cases are to be

decided with caution, according to Kenny.

E, an engineer, had left his place, by leaving an ignorant boy in

charge of an 'engine. The boy failed to stop the engine properly,

and. as a result of that, 'A' a worker died, held, E was liable, the

engineer-should have contemplated such a possibility.

vi) There are also cases where the victim's own conduct or

contributory negligence would result in a crime. These are to be

decided with sound reasons. This establishes the rule that both

mens rea and actus reus must concur to constitute a crime.

Objective and subjective standards :

Mens rea as one of the elements to constitute crime, was recog-

nised by the English courts by a slow process. In the beginning

the courts applied as objective standard. The courts applied its

own standard of what was right or wrong and tested whether

the prisoner had acted obedient to it or not. The view of the

prisoner was of no consequence.

This theory was replaced by subjective standard doctrine.

The court took into consideration the personality-mental and

physical- of the prisoner. This led to the examination of his

actual intention. This is the subjective test. For example, in

cases of self-defence or misadventure, where the prisoner kills

'A' according to the objective standard the court would award

him conviction, but would then be pardoned by the Crown.

However with the subjective standard of looking to the 'mental

element" the courts may acquit the prisoner on grounds of

private defence etc.

Conclusions : For application of the concept of actus non tacit

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

9

reum, nisi mens sit rea, at common law in England the

conditions are summarised, by Kenny, as follows :

1. The person (prisoner) must be of full age, of male sex, of

sound mind and living within the jurisdiction of the English

courts.

2. he must have committed the offence within the courts juris-

diction. Further, there must be "actus reus", that his conduct

must be voluntary and that he foresaw some consequences, the

nature of these is fixed by law.

Ch. .2. Mens Rea in statutory offences :

The old view was that the legislature should not override

common law. This has long been abandoned. In modern law the

statute made by the Parliament is paramount. Hence, in

interpreting the statute there is a presumption that mens rea is

part of the offence. This is a weak presumption and may be

rebutted by the statute itself.

After the 19th century, there was a marked move by the Parlia-

ment in regulating social life by creating offenses with light

punishment. The courts became inclined to solely interpret the

words of the statute, than imposing 'mens rea.

The leading case is R.V. Prince : P had taken a girl, out of the

possession and against the will of the parents. The girl was in

fact below 16, but P contended that she looked to be above 16

and hence, there was no offence. The courts held him guilty.

No reference was made to mens rea.

Though this was the trend set by the courts, still there are in-

stances where courts have in suitable cases insisted on proving

mens rea, on the basis of tr^e protection of the liberty of the

individual. In recent years, in respect of many of the offences

created by legislation, the courts have considered them as

exceptions to the rule of mens rea. In some, mens rea is held as

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

1

0

part of the offence.

In Kat V Diment, the prisoner was convicted for having used

false trade description, of "non-brewed vinegar'. It was held that

when a statute forbids the doing of an act, doing of it, itself

supplies mens rea.

Conclusions : Kenny concludes that it was not possible to for-

mulate any principle in statutory offences to say to what extent

mens rea is a constituent. The statute itself is the guiding star.

The ordinary rules of interpretation should be used. A statute

may directly exclude mens rea. R.V. Tolson : W, married H,

with the reasonable belief that her first husband was dead, as

he was not heard of for 7 years. There was no reference to

mens rea in the statute. Held, that mens rea is excluded in the

statute. W was held not liable as she had a reasonable belief

that her first husband was dead. The modern trend is to

exclude mens rea from statutory offences.

Ch. .3 . Mala in se and Mala prohibita :

The subjective standard doctrine of mens rea led to a

fallacious classification of crimes in England. Some were

serious and gave rise to deep moral reprobation. Such

offences were mala in se (bad in themselves) e.g. Homicide,

adultery, bigamy, slave trading, offences against God and

nature etc. (Blackstone).

Other offences "mala prohibita" (prohibited acts) were

breaches of laws which imposed duties without involving

moral guilt. Eg. : Not performing work on public roads. This

classification has no relevance today.

Mens rea and I. P. C.

In India, the concept is not applicable. The difficulty felt in

England, in interpreting mens rea, is obviated by the I.P.C.

and by Indian statutes. This is done by defining exactly, the

nature of the mental element of the accused.

The various offences in the I.P.C., require that the act (actus

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

1

1

reus) must have been done with the mental element:

"dishonestly", fraudulently", "knowingly", "intentionally",

"with intent to" etc. With this description the concept of mens

rea has been excluded from the definitions of offences.

Hence, it has no relevance to Indian Criminal Law.

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

1

2

CHAPTER 3

VARIATIONS IN LIABILITY

Ch. 3.1. Mistake as a defence at common law :

Kenny puts three special circumstances in which the criminal

guilt is lessened or entirely excluded. These are "mistake",

"intoxication" and "compulsion"'.

If mistake is to be considered as a good defense, three conditions

are to be fulfilled.

a) The mistake must be of such a nature that, if the supposed

circumstances were real, there would not have been any

criminal liability attached to the accused.

Mistake negatives mens rea and hence, the accused is not guilty.

It does not negative actus reus.

Accordingly to Foster, in a case, 'A' before going to the church,

fired off his gun and left it empty. In his absence, some person

took the gun, went out for shooting and on returning left it loaded,

later A returned, took up the gun and touched the trigger, which

went off and killed his wife. A had reasonable grounds to believe

that the gun was not loaded. Hence, he would not be guilty of

murder.

b) The mistake must be reasonable. This is a matter of

evidence. But, this is to be established to the satisfaction of the

Court ,A, in order to free his wife from a demon which had

possessed her, held her over fire and with a red hot poker, which

scared her. The wife died in consequence. A had reasonably

believed that he would free her from the devil, with his actus

reus. Held, A was guilty of murder.

c) Mistake however reasonable must relate to matters of fact.

The rule is

ignorantia facti excusat : Ignorance of fact excuses

ignorantia juris non excusat. Ignorance of law is no excuse.

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

1

3

An Italian who kept a lottery house in England was held guilty.

His plea that in Italy the act was legal and that he had mistaken

notion of English law, was rejected by the court.

In India, Sns. 76 and 79 deal with mistake of fact and mistake

of law (Refer Chapter 2,).

Ch. 3.2. Intoxication :

The old law in England, dealt with intoxication as one which

aggravated the crime and hence, punishable. But, in the present

day, the effect of intoxication is considered as similar to illness

produced by poison etc. Hence, actual insanity, produced by

drinking as in "delirium tremens", is a defence. This should be

established as a fact.

If the intoxication, is caused by a companion and not voluntarily

by the accused himself, then the accused is exempted. However,

it is to be established before the court that the accused was

incapable of knowing the nature of his act.

Relevance : Drunkenness may be relevant : i) to establish a

mistake ii) to show the absence of intention or specific

intention

iii) to show this as part of an offence e.g. drunken person in

charge of child of seven years, or drunken driver causing an

accident etc.

iv) to show that it has happened in provocation.

A in a fit of passion, is provoked and kills B, who was respon-

sible for the provocation. In some circumstances, this is

culpable homicide and not murder.

The general rule is that intoxication is not a defence but may be

relevant as stated above. The position in India is stated in Sn.

85. I.P.C. (See ch. 2.2.)

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

1

4

Ch. 3.3. Insanity

Insanity of a particular and appropriate kind is regarded as a

good defense in English law. Medical profession has classified

these mental variations.

The leading case is R.V. Mcnaghten. One M had killed Mr.

Drummond the private secretary of Sir Robert Peel. But, in

reality by mistake, he had killed not the real Mr. Drummond.

Insanity was the ground of defence. He was acquitted on this

ground. This caused great resentment and the House of

Lords stated certain principles as guidelines.

i) Every person is sane, until proved otherwise.

ii) At the time of committing the offence, the accused must be -

labouring from a disease of mind to lose his reason and to

know whether what he was doing was wrong or not.

iii) If he was conscious that the act was one which he ought

not to do, he is punishable.

iv) the nature of the delusion decides the question. The actus

reus must have been actuated by delusion directly.

The burden of proof is on the accused to prove his insanity

India : Sn. 84,1.P.C. insanity as a defence.

If the offence is done by a person, who at the time of doing it,

by reason of unsoundness of mind, is incapable of knowing the

nature of the act, or knowing the nature of what he was doing

was wrong or illegal, he is not guilty of the offence.

In Sakaram Ramji's case, the accused was a habitual ganja

smoker. He quarreled with his wife and killed her and the

children. The plea that he had a diseased state of mind due to

Ganja, and that he was incapable of knowing what he was

doing, was rejected by the court .Held Guilty of murder.

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

1

5

CHAPTER -4

PRELIMINARY CRIMES Attempt :

This is the most common of the preliminary crimes. It

consists of the steps taken by the accused in furtherance of

doing an offence, i.e.. The long chain of steps taken to reach a

stage to constitute the crime of attempt. This chain is the

actus reus".

To constitute attempt, there must be mens rea and actus reus

at common law, The actus reus consists of the deed done in

actual furtherance of the crime intended. This must show that

the accused was aiming at a crime. This means, he must have

taken some steps to do the crime or to attain his ultimate

objective.

The leading case is R.V. Robinson.

Robinson, a jeweler, had insured his stocks. One day he

bound himself up with a cord and called out for help. The

police came on the scene. R told the police, that a stranger

had come and tied him up and emptied the jewels. The cash-

box was open and empty. Later the police suspected the

story, and made a search and found the jewels under a safe.

He was charged for attempt to obtain money from the

insurance company, by false pretenses.

Held, not guilty. Kenny makes a clear analysis of this case. R is

not guilty because, the attempt had not yet reached that stage to

charge him. The actus reus was not there. If he had made

attempts to claim from insurance company, then of course there

would have been an attempt. However, in this case there was

no attempt, and hence, not guilty.

Completed act: When the attempt is completed it results in an

offense and the attempt -disappears. The accused becomes

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

1

6

liable for the completed offence.

India : Sn. 511 of the I.P.C. deals with "attempt" as a stage in

an offence.

CHAPTER - 5

PARTIES TO A CRIME

Crimes, in England, are grouped into 3 classes.

Treasons, felonies, and misdemeanor. The gravest is

treason, and the least of this crime is misdemeanours. Any

participation of the accused makes him guilty as a principal in

both these offences.

But the rules of common law relating to felonies are compli-

cated and the gradation of participation is to be decided to

award punishment. For this purpose, Kenny has divided the

parties into two groups : principles of the I degree and of the II

degree and Accessories before and Accessories after the fact.

i) Principals in the first degree :

He is the actual offender and the man with the guilty mind. The

actus reus is done by him generally. In some cases, the deed

may be done through an innocent person. The man who

instigates is the real offender. Thus, if a doctor tells the nurse to

administer a dose of medicine made by him, and if the patient

dies in consequence of the dose, the doctor is the principal of

the first degree.

There may be two or more persons in the first degree. If a night

watchman opens the main entrance of his masters house and

allows the accused to enter and steal the goods thereof, both are

principals of the first degree. Similarly, when A holds the tongue

of C and B cuts it off resulting in the death of C, both A and B

are principals in the first degree,

ii) Principal in the second degree:

These are the persons who aid and abet another in the commis-

sion of the crime. At common law, these were punishable

equally with the principal in the first degree, but, this was later

changed by the Accessories and Abettors Act 1861.

msrlawbooks Kenny Cr.Law .>>>>> P

a

g

e

1

7

The second degree man, is one who aids and abets at the

very time when the offence is committed, e.g. A person

who, aids in possessing explosives, a receiver of stolen

property from the thief; person keeping watch and ward

when the crime is going on inside the house, etc. Mere

presence, will not make a person, an abettor. There must be

evidence to show his participation.

iii) Accessories before the fact :

An accessory is a person who is absent at the time of the com-

mission of the felony, buy commends, procures, or abets a

felony. R. V. Saunders : in this case, S desired to kill his wife

so that he could marry M. He consulted Archer, who advised

him to put poison to apple. S did so. the wife after eating a

bit of the apple, gave to her female child which ate and died

in consequence.

Held, Saundes was guilty of murder. The court held that

Archer could not be held to be guilty as accessory to kill the

child since his aid and advice was to kill the wife and not the

child.

The principal, in criminal law is different from the principal

in tort or contract A, lodge owner, directs M, a maid servant

to steal jewels from the inmate of his lodge and M steals

them, the maid is the principal and the owner is the

accessory before the fact.

iv) Accessories after the fact:

An accessory in this case is a person who gives shelter or

relief in such a fashion as to avoid justice. He may conceal a

murderer in his house- mens rea is to assist him. Hence, a

person who harbours an offender is an accessory after the

fact. But, a wife is exempted and incurs no criminal liability

for giving shelter to her felonious husband.

THE END

But can we put an End to Crimes ?

You might also like

- Judges Make Laws or They Merely Declare ItDocument7 pagesJudges Make Laws or They Merely Declare ItasthaNo ratings yet

- Wills, Succession, Contracts, and Marriage LawsDocument2 pagesWills, Succession, Contracts, and Marriage LawsfcnrrsNo ratings yet

- The Haya de La Torre Case Between Colombia and Peru With Cuba As Intervening PartyDocument4 pagesThe Haya de La Torre Case Between Colombia and Peru With Cuba As Intervening PartyRobert ZrubanNo ratings yet

- 69 Bharat LLB 2nd Sem, HibaDocument9 pages69 Bharat LLB 2nd Sem, Hiba78 Harpreet SinghNo ratings yet

- Woman Law FDDocument16 pagesWoman Law FDShubham RawatNo ratings yet

- Final Draft Submitted in The Complete Fulfilment For The Course Civil Procedure Code For The Attaining Degree of B.B.A., LL.B (Hons.)Document24 pagesFinal Draft Submitted in The Complete Fulfilment For The Course Civil Procedure Code For The Attaining Degree of B.B.A., LL.B (Hons.)Aditi ChandraNo ratings yet

- VICARIOUS LIABILITY OF STATEDocument30 pagesVICARIOUS LIABILITY OF STATEMrinal MishraNo ratings yet

- Inchoate CrimesDocument156 pagesInchoate CrimesMandira PrakashNo ratings yet

- Povert and HungerDocument31 pagesPovert and HungerNida YounisNo ratings yet

- (Polity) Role of Civil Services in A Democracy PDFDocument9 pages(Polity) Role of Civil Services in A Democracy PDFPaladugu CharantejNo ratings yet

- Dr. Shakuntala Misra National Rehabilitation UniversityDocument11 pagesDr. Shakuntala Misra National Rehabilitation UniversityUtkarrsh MishraNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Sociology for Civil Services ExamDocument55 pagesIntroduction to Sociology for Civil Services Examvensri999100% (1)

- NJEP TDV Information & Resources Sheets Collected DocumentDocument77 pagesNJEP TDV Information & Resources Sheets Collected DocumentLegal MomentumNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts - KLE Law Academy NotesDocument133 pagesLaw of Torts - KLE Law Academy NotesSupriya UpadhyayulaNo ratings yet

- Community Service As PunishmentDocument20 pagesCommunity Service As PunishmentLelouchNo ratings yet

- Amity UniversityDocument10 pagesAmity Universityvipin jaiswalNo ratings yet

- No Fault Theory of DivorceDocument13 pagesNo Fault Theory of DivorceMayank KumarNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document17 pagesAssignment 2Riya SinghNo ratings yet

- Federalism Final Intro and ContentsDocument4 pagesFederalism Final Intro and ContentsShilpa DalmiaNo ratings yet

- Death Penalty: Abolition or Retention DebateDocument9 pagesDeath Penalty: Abolition or Retention DebatePrashantNo ratings yet

- The General Principles of Criminal Liability PPNTDocument24 pagesThe General Principles of Criminal Liability PPNTRups YerzNo ratings yet

- Res GestaeDocument4 pagesRes GestaeANSHU PRIYANo ratings yet

- The Indian Partnership Act 1932 Clearly Defines A PartnershipDocument8 pagesThe Indian Partnership Act 1932 Clearly Defines A PartnershipAman JangidNo ratings yet

- Cognizable OffensesDocument4 pagesCognizable OffensesAditya DayalNo ratings yet

- Death Penalty in IndiaDocument190 pagesDeath Penalty in Indiaabhinav_says0% (1)

- National Law Institute University: Law of Torts - I Trimester-IDocument19 pagesNational Law Institute University: Law of Torts - I Trimester-Ivatsla shrivastavaNo ratings yet

- The National Law Institute University Bhopal-1Document21 pagesThe National Law Institute University Bhopal-1Vikas Jadhav100% (1)

- MENS REA DOCTRINE EXPLAINEDDocument12 pagesMENS REA DOCTRINE EXPLAINEDMehwishNo ratings yet

- Mayank - Criinalogy 5th SemDocument9 pagesMayank - Criinalogy 5th SemMayank YadavNo ratings yet

- Everything You Need to Know About Summary TrialsDocument14 pagesEverything You Need to Know About Summary TrialsKritika KapoorNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Partial Restraint On Transfer of PropertyDocument14 pagesAnalysis of Partial Restraint On Transfer of PropertyPayoja GandhiNo ratings yet

- Gmail - Jurisprudence Notes - Concept of LawDocument7 pagesGmail - Jurisprudence Notes - Concept of LawShivam MishraNo ratings yet

- Comparative Legal System and Legal Pluralism - Chapter 1 by Joumana Ben YounesDocument14 pagesComparative Legal System and Legal Pluralism - Chapter 1 by Joumana Ben YounesJoumana Ben YounesNo ratings yet

- Medical Evidence: Dr. Himanshi PGT Student Department of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology AIIMS PatnaDocument36 pagesMedical Evidence: Dr. Himanshi PGT Student Department of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology AIIMS PatnahimanshiNo ratings yet

- HINDU LAW 5TH SEMESTER FinalDocument23 pagesHINDU LAW 5TH SEMESTER Finalvinay sharmaNo ratings yet

- Family Law ProjectDocument15 pagesFamily Law ProjectSakshi Singh BarfalNo ratings yet

- The Ethics of Advocacy in International ArbitrationDocument14 pagesThe Ethics of Advocacy in International ArbitrationSantiago CuetoNo ratings yet

- Right of Private DefenceDocument3 pagesRight of Private DefenceEnkayNo ratings yet

- Criminalization of Marital RapeDocument6 pagesCriminalization of Marital RapeAnuj Singh RaghuvanshiNo ratings yet

- Wrongful Restraint and Wrongful ConfinementDocument19 pagesWrongful Restraint and Wrongful ConfinementMir Ishrat NabiNo ratings yet

- Speedy Justice in India in View of Delay: A Project OnDocument18 pagesSpeedy Justice in India in View of Delay: A Project Onsorti nortiNo ratings yet

- MARITAL RAPE – Recognizing it as a crime under Indian lawDocument14 pagesMARITAL RAPE – Recognizing it as a crime under Indian lawSaurabh KumarNo ratings yet

- IPC - 5th - SemDocument60 pagesIPC - 5th - SemPràmòd BàßávâräjNo ratings yet

- Legal Theory - Critical ThinkingDocument4 pagesLegal Theory - Critical ThinkingJeffrey MendozaNo ratings yet

- Parenting Styles Research Paper English 1Document14 pagesParenting Styles Research Paper English 1Sarah PinkNo ratings yet

- Problemsstn of A Trade UnionDocument10 pagesProblemsstn of A Trade UnionAmit TiwariNo ratings yet

- Transfer of Property to Unborn PersonDocument60 pagesTransfer of Property to Unborn PersonjinNo ratings yet

- Dr. RAM MANOHAR LOHIYA NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY LUCKNOW Forest Conservation LawsDocument14 pagesDr. RAM MANOHAR LOHIYA NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY LUCKNOW Forest Conservation Lawslokesh4nigamNo ratings yet

- TOPIC 4 (Subject of International Law)Document9 pagesTOPIC 4 (Subject of International Law)Putry Sara RamliNo ratings yet

- CorporateCrimes AnIntroductionDocument11 pagesCorporateCrimes AnIntroductionKunwar SinghNo ratings yet

- Humanitarian LawDocument29 pagesHumanitarian LawAryanNo ratings yet

- Law of TortDocument28 pagesLaw of Tort19140 VATSAL DHARNo ratings yet

- Jury Trial DraftDocument14 pagesJury Trial Drafts. k. Vyas100% (1)

- International and Municipal LawDocument18 pagesInternational and Municipal LawAman RajNo ratings yet

- Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi Faculty of Law: Subject: Indian Penal Code IiDocument13 pagesJamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi Faculty of Law: Subject: Indian Penal Code IiShayan ZafarNo ratings yet

- Tribunalisation of Justice: Application of Droit Administratif in IndiaDocument9 pagesTribunalisation of Justice: Application of Droit Administratif in IndiaAkash AgarwalNo ratings yet

- New England Law Review: Volume 48, Number 1 - Fall 2013From EverandNew England Law Review: Volume 48, Number 1 - Fall 2013No ratings yet

- Kenny's Criminal Law PDFDocument18 pagesKenny's Criminal Law PDFsarthakNo ratings yet

- Kenny's Criminal Law: M. S. RAMA RAO B.SC., M.A., M.LDocument19 pagesKenny's Criminal Law: M. S. RAMA RAO B.SC., M.A., M.LShashank DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Workshop Summary 8-11-2014 Criminal Side-GadchiroliDocument19 pagesWorkshop Summary 8-11-2014 Criminal Side-GadchiroliAbhijit TripathiNo ratings yet

- Adverse Possession Law ExplainedDocument30 pagesAdverse Possession Law ExplainedRishabh ChorariaNo ratings yet

- Workshop Summary 8-11-2014 Criminal Side-GadchiroliDocument19 pagesWorkshop Summary 8-11-2014 Criminal Side-GadchiroliAbhijit TripathiNo ratings yet

- Safmarine Container Lines NV vs. Amita EnterprisesDocument13 pagesSafmarine Container Lines NV vs. Amita Enterprisesinpbm06330No ratings yet

- Res Judicata CitationDocument30 pagesRes Judicata Citationinpbm06330No ratings yet

- Workshop Summary 8-11-2014 Criminal Side-GadchiroliDocument19 pagesWorkshop Summary 8-11-2014 Criminal Side-GadchiroliAbhijit TripathiNo ratings yet

- Workshop 211214 Group ADocument26 pagesWorkshop 211214 Group AhimanshuNo ratings yet

- The Protection of Women From Domestic Violence Act 2005Document15 pagesThe Protection of Women From Domestic Violence Act 2005Bhagwandas GaikwadNo ratings yet

- Harinder Singh vs. Kuldeep SinghDocument9 pagesHarinder Singh vs. Kuldeep Singhinpbm06330No ratings yet

- Workshop Summary 8-11-2014 Criminal Side-GadchiroliDocument19 pagesWorkshop Summary 8-11-2014 Criminal Side-GadchiroliAbhijit TripathiNo ratings yet

- Consumer Forum CitationDocument10 pagesConsumer Forum Citationinpbm06330No ratings yet

- BDA CitationsDocument16 pagesBDA Citationsinpbm06330No ratings yet

- QM EnhancementsDocument2 pagesQM Enhancementsinpbm06330No ratings yet

- III Semester 3 Year LL.B./VII Semester 5 Year B.A. LL.B./B.B.A. LL.B. Examination, December 2014 JurisprudenceDocument2 pagesIII Semester 3 Year LL.B./VII Semester 5 Year B.A. LL.B./B.B.A. LL.B. Examination, December 2014 Jurisprudenceinpbm06330No ratings yet

- Sources of International Law LectureDocument79 pagesSources of International Law Lectureinpbm06330No ratings yet

- Notes Hindu Law I.Document17 pagesNotes Hindu Law I.inpbm06330No ratings yet

- Jurisprudence Jun 2011Document3 pagesJurisprudence Jun 2011inpbm06330No ratings yet

- Third Semester of (3 Yrs.) /seventh Semester of (5 Years) B.A. LL.B. and B.B.A. LL.B. Examination, December 2013 JurisprudenceDocument3 pagesThird Semester of (3 Yrs.) /seventh Semester of (5 Years) B.A. LL.B. and B.B.A. LL.B. Examination, December 2013 Jurisprudenceinpbm06330No ratings yet

- Criminal Law II PDFDocument20 pagesCriminal Law II PDFinpbm06330No ratings yet

- III Semester of 3 Years LL.B. Examination, January 2012 JurisprudenceDocument3 pagesIII Semester of 3 Years LL.B. Examination, January 2012 Jurisprudenceinpbm06330No ratings yet

- QM Enhancemenet PDFDocument5 pagesQM Enhancemenet PDFinpbm06330No ratings yet

- Jurisprudence - Dec 2012 PDFDocument3 pagesJurisprudence - Dec 2012 PDFinpbm06330No ratings yet

- Criminal Law II PDFDocument20 pagesCriminal Law II PDFinpbm06330No ratings yet

- UNIT I BasicsDocument31 pagesUNIT I Basicsinpbm06330No ratings yet

- LLB 2nd Semester Case List for Law of Torts and Consumer Protection LawsDocument20 pagesLLB 2nd Semester Case List for Law of Torts and Consumer Protection LawsRonak JainNo ratings yet

- SAP Order SplitDocument16 pagesSAP Order SplitabhijitknNo ratings yet

- Case Law Digest On Land Acquisition ActDocument107 pagesCase Law Digest On Land Acquisition ActSridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್100% (7)

- Injunction-Suit - HTML: Al-Ameen College of Law Civil Procedure Code Model Answer PaperDocument11 pagesInjunction-Suit - HTML: Al-Ameen College of Law Civil Procedure Code Model Answer Paperinpbm06330No ratings yet

- Contempt of Courts Act1971Document13 pagesContempt of Courts Act1971manvi11No ratings yet

- LatestEffective Specs HIIDocument390 pagesLatestEffective Specs HIIGeorge0% (1)

- Chapter 3 Introduction To Taxation: Chapter Overview and ObjectivesDocument34 pagesChapter 3 Introduction To Taxation: Chapter Overview and ObjectivesNoeme Lansang100% (1)

- Chem Office Enterprise 2006Document402 pagesChem Office Enterprise 2006HalimatulJulkapliNo ratings yet

- Au Dit TinhDocument75 pagesAu Dit TinhTRINH DUC DIEPNo ratings yet

- Cambridge IGCSE: 0450/22 Business StudiesDocument12 pagesCambridge IGCSE: 0450/22 Business StudiesTshegofatso SaliNo ratings yet

- Common SealDocument3 pagesCommon SealPrav SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- 69-343-093 NFP2000 ManualDocument56 pages69-343-093 NFP2000 ManualYoga Darmansyah100% (1)

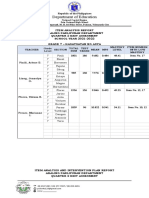

- Item Analysis Repost Sy2022Document4 pagesItem Analysis Repost Sy2022mjeduriaNo ratings yet

- 9 History NcertSolutions Chapter 1 PDFDocument3 pages9 History NcertSolutions Chapter 1 PDFRaj AnandNo ratings yet

- 1.18 Research Ethics GlossaryDocument8 pages1.18 Research Ethics GlossaryF-z ImaneNo ratings yet

- NLIU 9th International Mediation Tournament RulesDocument9 pagesNLIU 9th International Mediation Tournament RulesVipul ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Explore the philosophical and political views on philanthropyDocument15 pagesExplore the philosophical and political views on philanthropykristokunsNo ratings yet

- ISLAWDocument18 pagesISLAWengg100% (6)

- CVE A Peacebuilding InitiativeDocument8 pagesCVE A Peacebuilding InitiativeMulidsahayaNo ratings yet

- Tonog Vs CADocument2 pagesTonog Vs CAAllen So100% (1)

- Construction Agreement 2Document2 pagesConstruction Agreement 2Aeron Dave LopezNo ratings yet

- Catalogueofsanfr00sanfrich PDFDocument310 pagesCatalogueofsanfr00sanfrich PDFMonserrat Benítez CastilloNo ratings yet

- Classic Player '60s Stratocaster - FUZZFACEDDocument2 pagesClassic Player '60s Stratocaster - FUZZFACEDmellacrousnofNo ratings yet

- Faith Leaders Call For Quinlan's FiringDocument7 pagesFaith Leaders Call For Quinlan's FiringThe Columbus DispatchNo ratings yet

- Oblicon SampleDocument1 pageOblicon SamplelazylawatudentNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Modern Advanced Accounting in Canada 9th Edition Darrell Herauf Murray HiltonDocument35 pagesSolution Manual For Modern Advanced Accounting in Canada 9th Edition Darrell Herauf Murray Hiltoncravingcoarctdbw6wNo ratings yet

- Print: A4 Size Paper & Set The Page Orientation To PortraitDocument1 pagePrint: A4 Size Paper & Set The Page Orientation To Portraitnitik baisoya100% (2)

- Final Sociology Project - Dowry SystemDocument18 pagesFinal Sociology Project - Dowry Systemrajpurohit_dhruv1142% (12)

- Create PHP CRUD App DatabaseDocument6 pagesCreate PHP CRUD App DatabasearyaNo ratings yet

- Civics Unit 3 Study Guide: Executive, Legislative, and Judicial BranchesDocument5 pagesCivics Unit 3 Study Guide: Executive, Legislative, and Judicial BranchesEmaya GillispieNo ratings yet

- Foundations of Education Case StudiesDocument2 pagesFoundations of Education Case Studiesapi-316041090No ratings yet

- Cod 2023Document1 pageCod 2023honhon maeNo ratings yet

- Lc-2-5-Term ResultDocument44 pagesLc-2-5-Term Resultnaveen balwanNo ratings yet

- Assignment No 1. Pak 301Document3 pagesAssignment No 1. Pak 301Muhammad KashifNo ratings yet

- C - Indemnity BondDocument1 pageC - Indemnity BondAmit KumarNo ratings yet