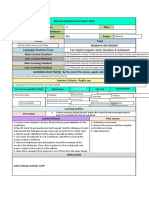

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Country Houses of Tasmania

Uploaded by

Cristian MuşatCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Country Houses of Tasmania

Uploaded by

Cristian MuşatCopyright:

Available Formats

COUNTRY HOUSES

of TASMANIA

COUNTRY HOUSES

of TASMANIA

Behind the closed doors of our nest private colonial estates

Photographs by Alice Bennett

Text by Georgia Warner

First published in 2009

Copyright Alice Bennett and Georgia Warner 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior

permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever

is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational

purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has

given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Bennett, Alice.

Country houses of Tasmania : behind the closed doors of our nest

private colonial estates / Alice Bennett, Georgia Warner.

ISBN: 9781741756524 (hbk.)

Bibliography.

Country homes--Tasmania.

Historic buildings--Tasmania.

Tasmania--History.

Other Authors/Contributors: Warner, Georgia.

728.3709946

Designed and typeset by Stephen Smedley, Tonto Design

Printed in Singapore by Imago

Colour reproduction by Splitting Image, Clayton, Victoria

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Thank you to every one of the amazing home owners who have helped

make this book possible, and who made it so enjoyable along the way.

Thanks especially to Michael and Susie Warner, Sandy Gray and Richard

and Sue Bennett.

vi | vi

Contents

1 Introduction

2 Beaufront

10 Belgrove

18 Belmont

26 Bentley

34 Peppers Calstock

44 Cambria

52 Cheshunt

60 Dalness

68 Douglas Park

76 Dunedin

84 Egleston

92 Ellenthorpe Hall

100 Exton House

108 Forcett House

114 High Peak

124 Higheld

132 Hollow Tree

142 Lake House

148 Mona Vale

160 Old WesleyDale

168 Quorn Hall

174 Summerhome

182 Valleyeld, Epping Forest

190 Valleyeld, New Norfolk

198 Vaucluse

208 View Point

216 Further reading

You are usually getting warm when you spot the cluster of exotic treesthe towering oaks, liquidambars,

chestnuts, elms, poplars and pines. Look closely and you might spy chimneys soaring within.

Or, if youre lucky, you might nd yourself driving along a deserted back road of rural Tasmania, only for an

imposing Georgian mansion to appear from almost nowhere and take your breath away.

Tasmania is blessed with a rich cultural heritage. Lesser known than some of the states famous convict-built icons

are the colonial mansions that were constructed by the early settlers who braved this wild and untamed land.

As these adventurers laid the foundations of Tasmanias ourishing agricultural industry, they also created an

antipodean England in the lavish homes they built. Some of these homes are still in the same families today.

This book not only showcases some of those amazing houses but also the incredible people who have passed

through them over the years, and through those people gives a glimpse into the colonial history of Tasmania itself.

With only a couple of exceptions, the properties you will be granted entrance to on the following pages are

private family homes. Please respect the privacy of these homeowners and the generosity they have shown in

opening their doors to you via the pages of this book.

Alice Bennett and Georgia Warner

Introduction

2 | 3

Cashed-up and in the market for land, young English

solicitor Philip Smith could hardly have timed his

arrival in Van Diemens Land better.

It was April 1832, and ten days before a proclamation

had been issued to announce the sale of 32,000 acres

of government reserve at Ross, in the Tasmanian

Central Midlands. The grazing land was to be sold in

eight blocks of 4000 acres in order to fund a

government home for orphans in Hobart.

Philip bought seven of the blocks on behalf of

family and friends and these combined to become the

Syndal and Beaufront estates, later known just as

Beaufront. And it is still some of the best ne-wool

producing country in the world.

Beaufront is believed to be named after the Duke

of Northumberlands Beaufront Castle, not because

of its distinctive Regency bow front, created from

carefully rounded, dressed sandstone.

The homestead was built for Philips brother Arthur

and his wife, and a stone in the cellar carries the

inscription Dennis and John Bacon, stonemasons,

1837. The elaborate fanlight and half side-lights in the

portico were later but still classical additions, as was

the two-storey, pre-1900 stone extension at the rear.

Within are a very ne hall and impressive formal

rooms, and a new kitchen and conservatory area

have sympathetically adapted the home for modern

family life.

It is not only the Beaufront home and its impressive

stone outbuildings, including stables likened to a

Palladian mansion, that are important historically.

The magnicent Beaufront gardens are also on the

Register of the National Estate. They are described by

the Australian Heritage Database as follows:

[A] rare Australian example of the transition from

the Arcadian to the picturesque landscape styles

demonstrates features such as spaces articulated

by stone and brickwalling, garden ornaments with

classical detailing used for focii, and the utilisation of

Beaufront

4 | 5

distant views as enframed visual features. The garden

has historical value for demonstrating the separation

of the private pleasure garden from the utilitarian

vegetable and picking garden. Aesthetically, the

garden provides a high quality visual experience, with

enclosed spaces, mature plants, structured views and

a rich variety of colour and form.

Beyond the formal garden area is a stunning

sandstone sundial that it is thought may have been

originally carved for the Ross Bridge. This stone

bridge, opened in 1836 and still taking trafc today, is

not just a local thoroughfare but an astounding work

of art. Former highway robber and convict Daniel

Herbert is believed responsible for the 186 elaborate

stone carvings on the side of the bridge, depicting

animals, Celtic symbols and people involved in the

construction.

The carving at Beaufront portrays an eagle

clutching a lamb. How it arrived in the paddock

below the stables remains a mystery, but it has been

speculated that some of the overseers at work on the

bridge may have sold government time and materials

to construct local buildings. Though the practice was

forbidden, it was nonetheless fairly common.

When Arthur Smith and his wife returned to

England in the 1850s, Beaufront was sold to Thomas

Parramore of nearby Wetmore, and in 1916 Beaufront

and Syndal were acquired by William von Bibra, who

farmed them with his brother Charles. The von Bibras

acquired adjoining land over time.

Williams son Donald von Bibra was a luminary in

the wool industry and a founding member of the

Australian Wool Board. He took on the management

of the property at the tender age of twenty and

involved Beaufront in many cutting-edge agricultural

research projects.

Donalds son Kenneth and his wife, Berta, took

Beaufront in some new directions, including the

creation of Tasmanias rst wildlife park and one of

the states rst deer farms. They were among the

earliest to capitalise on the tourism potential of the

tiny historic town of Ross, population 400the

wildlife park attracted 25,000 visitors a year.

Both Kenneth and Berta were, and remain, leading

members of the local community; between them they

have been involved in everything from municipal

government to party politics, the National Trust and

a variety of other community organisations.

The couple rst met in Tasmania and were

reacquainted in England, where Kenneth was studying

at the Royal Agricultural College in Cirencester. Berta,

meanwhile, had an intriguing role in one of the

greatest political scandals of the twentieth century:

the Western Australia-raised and Oxford-educated

lawyer had a watching brief for a person entwined in

the Profumo affair, to ensure they were not defamed

at the later trial of Dr Stephen Ward (who infamously

introduced the cabinet minister John Profumo to

showgirl Christine Keeler).

The tranquil countryside at Ross was a far cry from

all that, but Berta threw herself into sheep and cattle

breeding, raising children, and community life. She

and Kenneth have now retired to another historic

home at Longford, but their son, Julian von Bibra, and

his wife, Annabel, continue the family tradition today.

Julian and Annabel are deeply respectful of the

natural and cultural values of Beaufront and are

delighted with the opportunities their children have

growing up here.

Julian was encouraged to seek an education beyond

agriculture and studied economics at the University

of Melbourne, where he met Annabel who also

studied there. But, like his father, he went on to study

at the Royal Agricultural College in Cirencester, and

then returned to Beaufront.

Farming wont be foisted on the next generation of

von Bibras either, but there can be little doubt that

they will share their familys strong sense of pride in

being custodians of this precious part of the world.

6 | 6

8 | 9

10 | 11

As Peter Bignell tootles around in the tractor on his

historic sheep, beef and strawberry farm, youd swear

you could smell hot chips or dim sims.

You wouldnt be far wrong.

The owner of Belgrove, in Tasmanias Southern

Midlands, near Kempton, makes a habit of visiting

fried food establishments in the area to collect their

used cooking oil, which he converts to biodiesel to

power his tractor, ute and even his homes central

heating. The original Aga stove in the kitchen is next

in line for biodiesel conversion, which is just one of

Peters many ingenious little modications to this

grand old sandstone home.

Belgrove was built circa 1888 for Arthur Newell

Corney and his family, who came to this property from

Lake House at Cressy, near Launceston in the Northern

Midlands, which was constructed for Robert Corney.

It was the third house at Belgrove, the rst being a very

early cottage of which only sandstone foundations

remain, and the second dating back to the 1840s, parts

of which (such as the meat-house, bake oven and

dairy) stand in what is now the back garden.

In about 1903, the Corneys sold Belgrove to Arthur

Drysdale, known as the man with the Midas touch,

who at times also owned several other pastoral

properties, including neighbouring Mt Vernon and

Kelvin Grove.

In 1938, Drysdale sold Belgrove for 22,000 pounds

to concentrate on building his lavishly appointed

Wrest Point Hotel in Hobart. He later owned Hobarts

historic Hadleys Hotel and became the sole licensee

and proprietor of Tasmanian Lotteries after George

Adams Tattersalls empire transferred from Tasmania

to Victoria in the 1950s.

The farm passed into the ownership of the Headlam

and then the Hawker families before it was put on the

market again in 1999.

Sally Bignell didnt even know Belgrove existed

before she noticed the for sale sign on the Midland

Highway property as she drove past one day, even

Belgrove

12 | 13

though shed passed it countless times before. She

went to the open house and instantly fell in love.

Coming from a sprawling old cottage in the nearby

Central Highlands town of Bothwell, it was the perfect

upgrade: sandstone, stately, open and light.

But there were concerns about capitalising so much

on a house, and when Belgrove and its 130 hectares

were sold to the owners of a shorthorn cattle stud,

Sally resigned herself to the fact that it just wasnt

meant to be.

Eighteen months of drought followed and, on

another trip down the highway, Sally once again saw

a for sale sign on the white picket Belgrove fence. She

wasnt going to let it slip through her hands twice and

the transaction was completed in 2001.

Having been well looked after throughout the years,

there were no structural problems with Belgrove, but

it was dated. The bathroom was turquoise, the carpet

brown shagpile, there were multiple layers of wallpaper

on some walls, a washing machine was in the kitchen

because a laundry didnt exist, and the only downstairs

toilet was outside.

Sally engaged Hobart designer Mirella Bywaters to

assist with a full makeover of the interior of Belgrove,

with instructions that it combine the old with the

new and, most importantly, be practical and liveable.

And how much fun both Mirella and Sally must

have had scouring Tasmania, the mainland and

overseas for the perfect furnishings to set off each

room, such as the copper bath in his section of the

bathroom, the Italian ceramic toilet and red chandeliers

in her part, ttings to match the gleaming green Aga

stove in the kitchen, and stunning antiques, ornaments

and artwork for every corner.

Where appropriate, new built-ins were added, such

as the jarrah bookcase in Peters hunting-themed

ofce, which is adorned with a zebra skin and dark,

masculine furniture. The ofce also has a secret

lift-up door in the oorboards, under which Peter

has installed a row of containers holding beer and

wine supplies which run on mini train tracks for

easiest possible extraction.

Arthur Drysdale added the sunroom at the back of

the home, where nine servant bells line the wall. In

their rst week of living at Belgrove, Sally tried the bell

for the master bedroom in the middle of the night. Her

husband woke with such a jolt that he went downstairs

and opened the front door. But, Sally laments, thats as

much of a response as the ringing of servants bells

generates at Belgrove these days.

Unlike many Georgian sandstone mansions,

Belgrove is light and airy, both in its outlook and its

Baltic pine joinery and kauri pine oorboards. The

home is surrounded on two sides by a wide, two-

storey sandstone verandah featuring intricate iron

lace work. On the second storey, French doors open

onto a hall-sized balcony area, providing expansive

views across the entire Southern Midlands farming

district and up to the Central Highlands lakes district.

Positioned on the verandah below are a number of

sandstone urn owerpots carved by Peter Bignells

own hand, a skill he discovered when they were still

living at Bothwell. Sally had mentioned to her hus-

band one day how much shed like a sandstone

birdbath for the garden. Having never seen one in a

shop before, Peter decided to try making one with

sandstone from the quarry on the family farm.

Using his cars front axle like a pottery wheel, Peter

kicked the sandstone block around with his foot

while wielding an angle grinder. Friends who saw

Peters rst effort started placing orders. Then more

orders began arriving from Sydney, and not just for

birdbaths: sandstone Pooh Bears, big and small, were

a favourite for Peter (some he would swap for paint-

ings in the local art gallery). Decorative sandstone

balls were also in hot demandthe biggest weighed

two tonnes and had to be lifted with a front-end

loader onto a truck-axle lathe for carving.

Before long, Peters acclaim grew and he was asked

to restore the sandstone sundial in the Sydney Botanic

Gardens and undertake sandstone restoration work on

several public buildings in Hobart. His biggest job

involved carving the three-tiered fountain that is a

centrepiece of the conservatory at the Royal Tasmanian

Botanical Gardens.

When a commercial radio station ran an ad about

a sand-sculpting competition on Hobarts Kingston

Beach, Peters interest was piqued. From there began

a long reign as the Tasmanian king of sandcastles.

The Bignell family would head to the beach for the

annual competition, and they regularly left with rst

prize for sculptures that included a two-metre high

church and a similarly sized lighthouse. The principle

behind sand sculpting and sandstone sculpting is the

same, Peter condes: start with a big block, and then

carve the shape out.

It was only a matter of time before he set his sights

on a new challenge, winning a snow-sculpting com-

petition at Hobarts Antarctic Midwinter Festival

with a sculpture of a seal.

From there followed an invitation to compete in the

Russian Cup in November 2007, a prestigious inter-

national ice-sculpting competition held in the depths

of Siberia. Peter had never carved ice before but

modied some old shearing combs into chisels and

practised at Belgrove for months, carving the ABC

logo out of bricks of ice hed made in the deep freezer.

In Siberia, his team of two turned four tonnes of ice

into a whale-shaped helicopter during ve and a half

days of work in minus-twenty-ve-degree-Celsius

temperatures and sixty-kilometre-per-hour winds. It

was Peters carved ice gearbox cogs that actually turned

which won over the judges and secured the mayors

sculpture prize and an ugly, but unique, trophy.

These days, Peter is working on a new invention for

permanently xing cracks in walls. Hes been experi-

menting on Belgrove; it works, and he hopes to patent

Wisecrack soon.

14 | 15

16 | 17

18 | 19

For years, Belmont stared down on John Pooley twice

a day, as he drove between his Coal River Valley farm

and Hobart business.

By chance one evening he and his wife, Libby,

enjoyed a glass of wine in the stone-walled courtyard

by Belmonts blue-tiled pool. They fell in love with

the house. When friends who were renting it

mentioned the house might soon be sold, the Pooleys

snapped it up before it went on the market.

Five years later, the Pooleys still cannot believe their

luck as their stunning renovation job takes shape.

And theres a sense of serendipity in that, from the

converted stone stables, they are now running a cellar

door for their award-winning cool climate wines at

the property that was rst built for Hobart wine and

spirit merchant Benjamin Guy.

Belmont is set on a sandstone hillside that is itself

heritage listed, because it is from here that all the

sandstone that built Richmond village and its famous

bridge was quarried.

Guy bought the land in about 1833, and around

four years later the handsome home was built for

his family, which included at least eight children.

Only three years later the home and its forty acres

were advertised for lease, as the family left to visit

Europe.

Belmont has since had several owners; strangers

frequently make contact with the current landholders

to recount their own tales of growing up in this ne

Georgian home, while many more nd a visit to the

cellar door a very pleasant excuse for a closer

inspection of the property.

What so appealed to the Pooleys that evening by

the pool was just how light, bright, liveable and

positively Tuscan this place felt, a sense that was only

enhanced by its glorious outlook over the productive

Coal River Valley.

The homes spectacular outdoor areas include the

walled courtyard that spans the width of the home to

the old stables, the centrepiece of which is a stunning

Belmont

20 | 21

solar-heated pool surrounded by sandstone pavers,

olive trees and lavender bushes.

Plans are afoot to create a large formal garden

around the front terrace of the home, which commands

views over Pages Creek and then to the township of

Richmond. Meanwhile, at the back entrance, a new

sandstone patio has been positioned to catch the

evening sun.

The house has always been in good structural

condition, but it had a distinctly seventies feel to it

when the Pooleys moved in. The kitchen is now the

latest in design and three elegant casement windows

face onto the delightful courtyard and pool area. It

also leads into a dining room that features immaculate

cedar joinery and built-in cupboards, and which

looks out onto Richmond through French doors.

Unlike a great many houses of the era, this one was

built to capture both the views and the sun; so much

so that when former owner Eric Gray lived here, a

crystal bowl apparently burned a hole in his dining-

room table, so intense was the sun shining through.

The sitting room, with its marble replace, is yet to

be redecoratedLibby is leaning towards bright

yellow and white stripes to enhance the lightness of

the room. Also on the lower oor is a small study, and

an old kitchen that has been converted to another

cosy sitting room. Its massive replace incorporates

an intact bakers oven that will be used to learn the art

of wood-red pizzas with the help of a local chef.

Upstairs there are four bedrooms and two ultra-

modern bathrooms, his and hers.

Outbuildings include an old laundry, stables and

blacksmith shop, now converted to toilets for the cellar

door which are, according to most visitors, the only

ones theyve ever used with a replace and lounge.

The Coal River Valley produces some of Australias

nest wines and the Pooleys are one of its longest-

established winegrowers. When Johns father, Denis,

retired in 1984 from the car business they had

established together, he felt lost. Action had to be

taken, and so Denis and his wife, Margaret, bought

land next to John and Libbys Coal River Valley farm.

A founding member of Hobarts Beefsteak and

Burgundy Club, Denis Pooley wasnt up for farming

beef but decided to give the wine a go. Half an acre of

vines were planted at the Cooinda Vale Estate vineyard

and they couldnt have grown better.

John says it added ten years to his fathers life

because every year there was another vintage to look

forward to. Margaret still runs the Cooinda Vale cellar

door and, aged ninety-three, is the oldest female

vigneron in Australia.

After he moved to Belmont, John also planted vines

on nearby Butchers Hill, and 2007 saw the rst vintage

of pinot produced. Pooley Wines consistently wins

awards; its rieslings and pinot noirs took home no

fewer than twenty-two medals and trophies at the

2007 Tasmanian Wine Show.

These days, as they enjoy an evening glass of wine

from their own cellar door in the beautifully designed

courtyard, John and Libby marvel at their good

fortune in living here. They also feel strongly that

they are simply caretakers of this magnicent property

for the next generation, in this case their son, Matthew,

who is now running Pooley Wines, and his wife and

children.

22 | 23

24 | 25

26 | 27

It was by chance that John and Robyn Hawkins

found themselves in the Chudleigh Valley, touring

on a back road between Deloraine and Cradle

Mountain. On passing through the narrow eye of the

needle entrance to the Chudleigh Valley they found

a stunning landscape laid out before them. So when

Bentley, one of the districts original land grants, came

onto the market, the memory of this beautiful vista

eventually lured the Hawkins from Moss Vale, in the

New South Wales Southern Highlands, to Tasmania.

They have dedicated the last ve years to the

creation of a splendid country house through

signicant additions to the original homestead, laying

hedges, building dry-stone walls, creating lakes and

restoring outbuildings. And apart from Government

House in Hobart, Bentley is also Tasmanias rst and

only heritage-listed landscape.

But this is of little consequence to John Hawkins

when what he considers the greatest threat to the

surrounding mountain landscape, the clear-felling of

native forest, is exempt from all heritage legislation.

John believes no other state or country would permit

such sacrilege, and he despairs at the visible scars on

the surrounding Tiers and the loss in the Chudleigh

Valley of some of Tasmanias nest agricultural land

to tree plantations.

Life has certainly become a little livelier in the sleepy

village of Chudleigh since the Hawkins arrival. But

more than anything, locals credit John with completely

recharging the valley and giving them a great sense of

pride and appreciation of its visual signicance as a

unique, re-farmed Aboriginal landscape overlaid by

European settlement.

Bentley was a land grant in 1829 to John Badcock

Gardiner who, it is assumed, named Chudleigh after

his local village in Devon. Along with a couple of

other early landholders in the district, Gardiner

struck paydirt by burning lime and sending it to

Launceston for building work. The whole valley is

home to the most important limestone karst in the

Bentley

southern hemisphere, which is listed as the Mole

Creek Karst on the Register of the National Estate.

More land was added to the Bentley estate by its

next owner, entrepreneur Phillip Oakden, who, among

other things, introduced blackberries to Tasmania and

brought Lincoln sheep to graze his land. A founding

member of the Launceston Horticultural Society and

the Union Bank in Launceston, Oakden was

responsible for planting more than six miles of

hawthorn hedge that is such a feature of the property

today. The hedges were admired as early as 1870 by a

passing traveller:

The road for a mile before reaching Chudleigh

passes through what is called the Bentley Estate and

is bordered on each side with the nest hawthorn

hedges that I have ever seen out of England, planted

28 years ago, standing from 15 to 20 feet high; the

smell of English grass hay which was then on the

ground lent a great charm to this part of the journey.

I could not help envying the lot of the residents of

such a delightful spot.

The property underwent further ownership changes

before it was sold to Donald Cameron of Nile, in the

Northern Midlands, to be farmed by his son, Donald

Norman Cameron, who represented Tasmania in the

rst federal House of Representatives. The Cameron

family built the Bentley homestead in 1879, an elegant

single-storey house based on a Melbourne town villa.

According to John Hawkins, the most famous

episode in his career in the federal parliament was

when it was being debated whether the federal capital

should be built at Canberra or some other site. The

decision lay with him. He kept silent for two weeks,

tantalising the people of Australia by refusing to say

which way he was going to vote; in the end he voted

for Canberra.

After Donald Norman Camerons death in 1931,

Bentley changed hands a few more times and was

subdivided along the way. When it was bought by John

and Robyn Hawkins, the acreage stood at 560 but this

has since been more than doubled, as has the size of

the villa to create one of the rst important Tasmanian

country homesteads of the twenty-rst century.

The original house is now one wing and its replica

another. Connecting the two is a conservatory which

is crowned with an elaborate cupola inspired by the

dome on the Royal Pavilion at Brighton. With its

eleven north-facing windows, the conservatory

captures the sun to warm the buildings core. And

with restoration of the old stables in progress and a

clock now installed in the clock tower, the property is

once again a large working estate.

Almost as breathtaking as the house is the new dry-

stone wall that surrounds itat 700 metres, it took

three years and 2500 tonnes of rock to build, with two

men from Deloraine receiving training from an

English dry-stone walling and hedge-laying expert,

here on a teaching holiday in 2003. The hawthorn

hedges have been correctly laid, pleached and staked

at blood horse height, and John Hawkins has found

that a tea-cutting machine from his Japanese antique

business doubles nicely as a hedge-trimmer, producing

the perfect curve.

Everything at Bentley has been done with the

landscape in mind. Robyn Hawkins, who created the

famous garden at Whitley in the New South Wales

Southern Highlands, is responsible for the design of

the grounds, the planting of 50,000 native trees and

the creation of the grass garden along the creek.

The history of the estate was in part described by

John Hawkins in the Australian Garden History

Society newsletter, Blue Gum:

The whole valley is presided over by the Gog range,

this features a natural rock formation that, in the

morning light, produces a perfectly formed human

face some 200 feet high. It was from this ridge that

the Aboriginals gathered their ochre; OConnor,

the Land Commissioner, called this area the City

of Ochre in his survey of 1828. Europeans, under

Captain John Rolland, of the Third Regiment, spent

nine days mapping the course of the Mersey River in

1823. On climbing the top, he named the ridges Gog

30 | 31

and Magog, the classical names for a King and his

supposed Kingdom Rolland must have been of a

literary and artistic bent for apart from the highest

peak, which he named after himself, the two peaks

to the west he named Vandyke and Claude, after the

great European landscape painter

The rural landscape is largely as created by

Aboriginal re farming and European settlement in the

nineteenth century. The land grants were taken up

over re farmed cleared oodplains created by Native

Hut Corner Aboriginals over thousands of years.

Not having to clear the trees made this land instantly

valuable and protable to European settlers. Their

landscape was to be contained by hawthorn hedges, the

native trees cut to copse, thereby protecting the ridge

lines so as to create a large, still-existing parkland, later

planted with European trees, all much in evidence.

On learning that the listing of Bentley and its land-

scape with the Tasmanian Heritage Register provided

no protection from the clear-felling of forests on

surrounding hills and mountains, John has lobbied for

changeso far without success. He believes the Tas-

manian government is too closely aligned to the

forestry industry, particularly in the matter of exemp-

tion of forestry from all heritage legislation.

In an exhaustive review of this legislation for the

Labor state government, it was recommended by

consultants that such statutory exemptions should be

removed and canvassed options for how to better

protect historic cultural heritage landscapes, which are

also exempt from protection under the legislation.

When pursued on the issue of exemptions, the

governments response was: These provisions will

remain at this time.

John Hawkins, a Sandhurst-trained former British

army ofcer, is determined to reverse this scenario

and is leading the charge in the valley for the

preservation of this historic and beautiful Arcadian

landscape into the twenty-rst century.

32 | 33

34 | 35

Few get the opportunity to laze about a stately

Georgian mansion and absorb all the grandeur it

evokes. The homes you enter in this book are private.

Unless you are part of their inner circle, you might

not have even known they existed. As for those who

live in themwell, theyre usually too busy running

farms, raising families and keeping on top of never-

ending maintenance to ever really get the chance to

sit back self-indulgently.

So thats where Peppers Calstock comes in, an

impressive home steeped in Tasmanian history

offering luxury accommodation and ne dining.

And yet its the placement of this magnicent

building in the landscape that is possibly its greatest

appeal. Deloraine, in Tasmanias Central North, is

picture-postcard stuff. Its a historic town on the

Meander River, where you can try your luck for trout,

surrounded by lush green farmland complete with

hedgerows. The rugged Great Western Tiers are on its

doorstep, and behind them the Tasmanian Wilderness

World Heritage Area. Black trufes, cheese and honey

are just some of the produce for which this area is

renowned.

Framed by giant oak trees, Calstock sits at the bot-

tom of the 1228-metre Quamby Bluff on the Western

Tiers. The mountain forms the spectacular backdrop

while the home gazes down over the farmland, river

and town.

Calstock was designed to take full advantage of

these views. For example, the original windows in the

main living areas sit atop panels that can be opened

like little doors; when the windows are right up and

the panels open, it is possible to walk straight out

from the lounge or dining room onto the wide

agstone-paved verandah, creating an indoor

outdoor entertaining area.

The rst owner of Calstock was Lieutenant Pearson

Foote. He received the land grant in about 1830 after

starting out as a settler in Western Australia but

nding the going too tough. Foote was forced to sell

Peppers Calstock

36 | 37

Calstock in the depression of the 1840s, and it

subsequently became a property of the Field family.

The family patriarch, William Field, had been

transported to Australia for receiving nine stolen

sheep as a butcher and made a fortune out of cattle

farming in Tasmania after he was freed. When he died

in 1837, Fields wealth was estimated at 1.238 per cent

of the countrys GDPbillions of dollars, in todays

termsand he owned one-third of all the land and

buildings in Launceston.

Westeld, Eneld, Easteld and Woodeld were

among the Tasmanian properties William Field

acquired. He built impressive homes on the land and

left them to his four sons. His third son, Thomas,

inherited Westeld and in the 1850s purchased

nearby Calstock. Thomas added the main part of the

present house complete with its wide verandah on

three sides and distinctive open balcony on top.

The Fields were keen on racehorses, and Thomas

turned Calstock into Tasmanias top racing stud from

where two Melbourne Cup winners were bred,

including the mighty Malua. Malua and his brother,

Stockwell, were bought by former premier of

Tasmania Thomas Reiby at one of Calstocks two-day

yearling sales. Reiby was determined that a Tasmanian

horse would win the Melbourne Cup, and Stockwell

did indeed lead all the way down the nal straight in

1882only to be pipped at the post. It is said the

dramatic second-place nish so frustrated Reiby that

he got out of racing then and there, selling Malua to

J. Inglis of Victoria.

The Australian Racing Museum describes Malua as

the most versatile of all Australian champion

gallopers; from sprints to staying events, and even the

steeplechase, he left them all in his wake. His many

wins in 1884 included the 1000-metre Oakleigh Plate,

then Australias richest race, the 2600-metre Adelaide

Cup, and the 3200-metre Melbourne Cupwon by

half a head in front of 90,000 people.

Maluas brother Street Anchor, also bred at Calstock,

won the Melbourne Cup the following year, while his

son Malvolio won the 1891 Cup and another son,

Ingliston, won the Cauleld Cup in 1900.

And Maluas racing career didnt nish when

he was put out to stud. At the age of nine he

was entered in his rst steeplechase, reportedly after

Inglis watched him clear a high fence in the yards.

Carrying Inglis himself, who weighed in at seventy-

three kilograms, Malua romped home in the

three-mile VRC Grand National Hurdle. His last

hurrah was taking out the 2800-metre Geelong Cup

as a ten-year-old.

In his home town of Deloraine, a committee is now

raising money to build a monument to the mighty

Malua, and as a guest at Calstock you are free to walk

through the legendary stables where he was reared.

Calstock remained in the Field family until 1971,

then was the focus of a couple of separate efforts to

redevelop it into a thoroughbred stud. It was pur-

chased by the current owners just before 2000, restored

and turned into a guesthouse.

In 2005 it became part of the Peppers chain, and in

September 2006 Linda and Daniel Tourancheau

moved in as managers, viewing Calstock as the per-

fect place to combine their skills and full their

long-held desire to move to Tasmania. Linda is the

highly trained hotel manager half of the equation,

Daniel the French chef classically trained in Michelin-

star restaurants.

With their sixteen-foot high ceilings, the rooms are

massive in proportion, each ornately decorated in a

different style. Read about William Field in the library,

take an aperitif in the lounge and then proceed to the

dining room for a three-course set-menu dinner that

is a drawcard in its own right.

The menu is dictated by what is fresh, local and in

season, from locally harvested black trufes to

venison, and zucchini owers from the garden. Even

if there are only two guests staying, Daniel is up at the

crack of dawn making the croissants for breakfast

and, later, the bread for the evening meal. Theres a

wine for every occasion on the list.

Peppers Calstock showcases the best of Tasmania

from one of its beautiful Georgian mansions, and

allows anyone the chance to experience one of these

properties in truly decadent style.

38 | 39

40 | 41

42 | 43

44 | 45

Early settler Louisa Anne Meredith was a prolic

illustrator and writer, and when she came to Tasmania

in 1839 with her husband, Charles, and their baby

son, they stayed at Cambria, regarded then as the

government house of the states east coast. Louisa

described it in her book, My Home in Tasmania:

The House at Cambria commands an extensive view

of large tracts of bush and cultivated land; and across

the Head of Oyster Bay, of the Schoutens, whose

lofty picturesque outline and the changing hues they

assume in different periods of the day or states of the

atmosphere, are noble adjuncts to the landscape.

Below a deep precipitous bank on the south side of the

house ows a winding creek, the outlet of the Meredith

River, gleaming and shining along its stony bed

A large, well-built cheerful-looking house, with

its accompanying signs of substantial comfort in the

shape of barns, stackyard, stabling, extensive gardens,

and all other requisite appliances on a large scale, is

most pleasant to look upon at all times and in all

places, even when tens or twenties of such may be seen

in a days journey; but when our glimpses of country

comfort are so few and far between as must be the case

in a new country, and when ones very belief in civil-

isation begins to be shaken by weary travelling day after

day through such dreary tracts as we had traversed, it

is most delightful to come once more among sights

and sounds that tell of the Old World and its good old

ways, and right heartily did I enjoy them.

The noble verandah into which the French windows

of the front rooms open, with its pillars wreathed about

with roses and jasmine, and its lower trellises hidden

in luxuriant geraniums, became the especial abiding

place of my idleness; as I felt listless and inactive after

my years broiling in New South Wales, and delighted

in the pleasant breezy climate of our new home

A large garden and orchard, well stored with the

owers and fruits cultivated in England, were not

amongst the least of the charms Cambria possessed

Cambria

46 | 47

in my eyes; and the growth of fruit trees is so much

more rapid and precocious here than at home, that

those only ten or twelve years old appear sometimes

aged trees

The orchard, with its ne trees and shady garden

walks, some broad and straight, and long, others

turning off into sly, quiet little nooks, was of great

delight to me the cultivated owers here are

chiey those familiar to us in English gardens, with

some brilliant natives of the Cape, and many pretty

indigenous owering shrubs interspersed.

Cambria, a twenty-seven-roomed Georgian man-

sion, was designed by Lieutenant George Meredith,

one of the east coasts rst settlers and Louisas father-

in-law. The building work commenced in 1830 and

Cambria took six years to complete, though Meredith

had been developing the gardens for the best part of a

decade, hence their well-established state when

described by Louisa in the early 1840s.

Cambria has an unusual colonial bungalow style at

the front with four sets of glazed French doors

opening onto the noble and wide verandah, which

has a colonnade and balustrade of wood and is paved

with square sandstone set on a diagonal.

From the front, Cambria appears to be only one-

storey high, plus a great deal of roof, but the back of

the house, which is cut into a hill, reveals its true scale.

Here three storeys are evident, the top an attic with

quaint dormer windows that face away from the

homes glorious views over Great Oyster Bay across to

the Freycinet Peninsula.

Marble replaces downstairs are complemented

upstairs by what is thought to be a rare example of

marbling wallpaper, or simulated marbling.

The front hall is unusual in that it has two cedar

fanlit doors concealing the stairs: behind one door

the stairs go up, behind the other, down.

The large drawing room was once the scene of

dances that George hosted for visiting naval ofcers,

their ships anchored just a short distance away.

Among the extensive outbuildings were a kitchen,

brick stables and timber barn, along with a toilet

building that boasted a three-seater loo, each one a

different size.

In 1841, Louisa and Charles set about building their

own place at Spring Vale, just north of Swansea, but

they then resettled at Port Sorell in the north-west, and

later lived in various other parts of the state.

George Meredith died in 1856 and Cambria stayed

in the Meredith family until it was leased, and later

purchased, by the Bayles family. Basil Bayles, a local

identity, lived in the homestead with his sister until

1949, although the upstairs section was never really

used in this time and started to show its years. A short

ownership by the Brettingham-Moores followed before

Cambria was sold to the Burbury family in the 1970s.

Nick and Mandy Burbury have now called Cambria

home for thirty years, longer than George Meredith

did, and theirs were the rst babies to be raised here.

The home wasnt exactly designed with a young family

in mind, but recent additions, such as a new kitchen/

conservatory area have made it an easier place to live.

Cambria has also been recently re-roofed, and other

restoration jobs are on the agenda.

The gardens at Cambria have, like the adjoining

5000-hectare farm, suffered from prolonged drought,

but still resemble some of Louisas elaborate

descriptions, notwithstanding the fact that she may

have been prone to a little poetic licence.

Louisa Merediths other writings include Some of

My Bush Friends in Tasmania, Tasmanian Friends and

Foes, Feathered, Furred and Finned, Bush Friends in

Tasmania, and two novels. She took a great interest in

politics, was an early member of the Society for the

Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and inuenced her

husband to legislate to protect native wildlife during

his many years as a member of the Tasmanian

Legislative Council.

Flora and fauna also feature heavily in My Home in

Tasmania, including the trials and tribulations of

trying to tame a possum, and her description of the

capture of a Tasmanian tiger:

I pitied the unhappy beast most heartily, and would

fain have begged more gentle usage for him, but I was

compelled to acknowledge some coercion necessary,

as, when I softly stroked his back (after taking the

precaution of engaging his great teeth in the discussion

of a piece of meat), I was in danger of having my hand

snapped off.

Her ora and fauna drawings also won many

awards, and in 1884, after her husbands death, the

Tasmanian government awarded Louisa a pension of

one hundred pounds a year for distinguished literary

and artistic services to the colony. She died in Victoria

in 1895, survived by two sons.

48 | 49

50 | 51

52 | 53

Of all the members of Tasmanias Archer dynasty,

William Archer has been described as the most

brilliant. The rst Tasmanian-born architect is

credited with designing some of the states most

magnicent buildings, from the elaborate Italianate

villa that was added to his fathers home, Woolmers,

to his pice de rsistance, Mona Vale at Ross.

Archer was also an acclaimed botanist who studied

at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, and he contributed

in such a way to Sir Joseph Hookers authoritative work

on Tasmanian botany, Flora Tasmaniae, that it was

jointly dedicated to him.

He was also noted for his engineering, mainly in

regard to surveying and designing irrigation channels

to provide water for domestic animals and for ood

irrigation.

It was at Cheshunt, in Meander Valley in Tasmanias

Central North, that he combined his passions. The

mansion is the home that William Archer designed

for himself; in its gardens he planted exotic trees, and

in the surrounding forest, wilderness areas and on

river banks he collected many native plant species,

some of which, such as the conifer Diselma archeri,

bear his name.

William Archer was the third son of Thomas

Archer, the founder of this great Van Diemens Land

dynasty, who arrived in Tasmania about 1813. Before

long, Thomas had established the vast estate of

Woolmers near Longford, south of Launceston, and

his success inspired his father and three of his brothers

to also make the move to Van Diemens Land. The

Archers soon owned tens of thousands of acres of

prime farming land throughout the district, Cheshunt

representing some 7000 acres on the western fringe.

At the age of sixteen, William went to London to

study architecture and engineering, and his rst job

upon returning home was aggrandising Woolmers.

The palatial Mona Vale, which he designed later for

his brother-in-law, Robert Kermode, has been

described as the largest private home in Australia.

Cheshunt

54 | 55

Mona Vale is also known as the calendar house for its

365 windows, fty-two rooms, twelve chimneys and

seven entrances.

Other building designs credited to Archer include

the old Hutchins School building in Hobart, the main

building of the former Horton College at Ross, and

the two-storey addition to his brothers home, Faireld

at Cressy.

Archers work is mostly Victorian in manner and

Italianate in style, although Cheshunt is considered

quite unusual. It has been described as an example of

architectural eclecticism, with its large Georgian

mansion, Victorian verandah and Italianate tower.

On the rst level of the exterior brickwork quoins

feature, while on the second level double pilasters

grace the corners. The chimneys are ornate, the

windows double-paned, and at the back a square

tower has narrow Italianate windows. Connecting the

two wings at the front is a two-storey verandah, with

the iron frieze, brackets and balustrade all boasting

different designs.

Inside are twenty-three rooms, including nine

bedrooms and an entry hall with a replace, which

was said to be a mark of distinction. Cheshunt also

has several brick-nogged, timber-clad outbuildings,

including stables, a carpentry shop, a butchery and

a blacksmith shop.

The foundation stone for the home was laid in

1850, and the centre and eastern wings completed

about 1852. A few years later, Archer set off to study

botany at Kew, where he also contributed to Hookers

Flora Tasmaniae. A stint in Melbourne followed where

he tried, unsuccessfully, to earn money as an architect

before he sold Cheshunt in 1873, the house still not

complete. William Archer died a year later at his

brothers farm, Faireld, broken and impoverished,

leaving an annuity of just one hundred pounds for

his wife and twelve surviving children.

The new owners were William and John Bowman,

themselves part of a pioneering farming dynasty from

South Australia. Williams son Frederick took owner-

ship of Cheshunt in 1879, and a few years later

married Gertrude Field from the nearby Calstock

estate. Also connecting the two colonial properties

was an early, direct phone line.

In about 1885, the Bowmans started work on

completing Archers design, employing a live-in

brickmaker who churned out 100,000 bricks in the

space of a couple of months.

Look closely at the faade and youll notice that the

northern and southern wings are different sizes. The

verandah posts in between have been placed off-

centre to balance the appearance.

Before Frederick died in 1929 he left Cheshunt to

his grandson Ronald so as to avoid paying death

duties. It would be another forty years before Ronald

moved in but for much of this time Cheshunt was

occupied by Ronalds grandmother and aunt,

Stephanie, a period in which they endured the Great

Depression and World War II.

Though Stephanie spent nine years in hospital

before her death in 1969, no one had the heart to

displace her from her long-time home, so it wasnt

until the early seventies that Ronald and his wife,

Leila, braved the move to Cheshunt.

The house was by now in a sad state, and rats, mice

and silversh had well and truly moved in. The roof

was leaking, plaster had fallen from the ceiling and

many of the wooden oors were rotten. The interior

was dirty, dusty and dampthree wheelbarrow-loads

of soot were carted away from the old slow-

combustion stove in the kitchen.

After completing the most urgent structural jobs

and cleaning the grime, the Bowmans restored a

room every couple of years and repolished the

antiques. This bit-by-bit interior renovation has

continued since the latest generation, Paul and Cate

Bowman, arrived in 1985. The bottom oor is now

basically complete; work on the upper level with its

six bedrooms continues, but it is only ever used when

guests come to stay.

In 1998 the Cheshunt exterior got a major new

lease of life. The roof and rotten verandah were

replaced, and the chimneys repaired with the help of

a crane. The exterior walls were pressure-cleaned and

then given three coats of paint, a process that took a

team of ve painters ve weeks to complete.

At one stage Cheshunt was painted in blood and

bandages stylered walls with contrasting sandstone

quoins. The Bowmans considered returning it to this

colour but ultimately opted for more muted tones,

although one outbuilding remains in blood and

bandages style.

Considerable preservation has also been undertaken

on the other outbuildings.

The renovation efforts at Cheshunt are limited by

time and funds. Its an exhausting and never-ending

task to look after a home such as thisit was built to

be staffed, for one thingand matters have not been

helped by adverse seasons.

It seems that life has always been a little bit harder

at Cheshunt than at the foundation Archer farm,

56 | 57

Woolmers. When William Archers oldest brother,

Thomas (II), died suddenly at the age of twenty-six,

followed a few years later by his father, Thomas (I),

Woolmers was left to his ten-year-old nephew,

Thomas Archer (III).

In his will, the elder Thomas bequeathed various

annuities that were to become millstones around the

necks of William and his other brother, Joseph, of

Panshanger at Longford. The collapse of a family

bank and the agricultural depression compounded

matters, and William was increasingly struggling at

Cheshunt. It appears that he was never paid a cent for

his architectural work, which he limited to doing for

the church, family and friends.

Back at Woolmers, the subsequent generations of

Thomas Archers (III, IV, V and VI) lived the life of

landed gentry, pursuing interests such as travelling,

golf and entertaining, before the last male heir died in

1994, having been a virtual recluse in the magnicent

homestead all his life.

Woolmers is open to the public and is also home to

the National Rose Garden.

Cheshunt is not quite the perfectly manicured

horticultural showpiece that its grander relation is,

but the old exotic trees that surround the homestead

are a reminder of William Archers important botanical

work. They include giant oaks, elms, chestnuts,

Japanese cedars, laurels and American cottonwood

trees. Botanists still call by Cheshunt today looking

for examples of Archers work.

58 | 59

60 | 61

Clan Mackinnon was descended from royal Scottish

blood, and in its heyday controlled vast areas of land

on the Isle of Skye, in the northern Scottish highlands.

The clan was turfed off these lands for supporting

Bonnie Prince Charlie in the Jacobite uprising, which

had hoped to restore the House of Stuart to the throne.

During the clearances that ensued, tens of thousands

of highlanders were rounded up and forced to settle

on poor land by the sea, to make way for large-scale

sheep farming and to ensure the collapse of the old

clan system.

It was in this context that a young Allan MacKinnon

determined he had no future on Skye anymore, and

set off alone for Van Diemens Land, arriving in 1822.

With great difculty, Allan obtained a land grant

near Evandale in the Northern Midlands of Tasmania,

but he ultimately had to vacate it because of the

constant trouble he encountered with the original

Aboriginal occupants. Instead he ran the Launceston

prison until he had the means to buy Dalness, located

about one mile from his original land grant. Dalness

has been the home of members of the prominent

MacKinnon family ever since.

The 500-acre property was originally granted to a

Captain Donald MacDonald, who presumably had

connections to Clan MacDonald in Dalness, Scotland.

After he died in 1835, his widow sold the property to

Allan MacKinnon, although there would later be a

dispute over whether or not he had title.

In about 1839 MacKinnon built himself an ultra-

fashionable home for the era, Georgian Regency in

style with unusual red-face brick; the bricks were

made on the property in a paddock that has ever since

been called brickeld.

The home looks down over undulating elds and

across to Ben Lomond. Around it were planted at

least a hundred oak trees, an orchard and superb

gardens, in which a small summerhouse was built.

In contrast to the symmetry associated with Geor-

gian homes of this time, Dalness has an irregular

Dalness

62 | 63

interior plan; this style, in which rooms of different sizes

feature in a home with a traditionally composed faade,

would become more common in the Victorian era.

The main entrance to the home is framed by an

imposing Doric doorcasea design replicated over

one of the replacesand an intricate rectangular

fanlight. Internally, the outstanding cedar ttings

bear a remarkable resemblance to those at Woolmers

and Exton House.

The home is three bays wide, and the cedar staircase

in the hall is highly unusual as it appears to have

originally turned upwards to the left, but was at some

point switched to turn to the right.

The main homestead block was balanced by wings

at each side, however only one remains, and this was

rebuilt in the 1920s.

Allan MacKinnon married a Maclean girl from down

the road who had also emigrated from Scotland with

her family, and they had six children. Their male

descendants ended up farming signicant properties

throughout the district, including Vaucluse, neigh-

bouring Glen Esk, and Mountford and Wickford at

Longford. Their daughters married into other prom-

inent local families. With the exception of Vaucluse,

MacKinnons still run all these properties today. After

Allans success in Australia, his brothers followed him

out, as did many other related MacKinnons whose

descendants can still be found in all corners of the

country.

Every generation of MacKinnon has done its own

bit of tinkering with Dalness. In the 1960s the entire

southern wall of the main block had to be rebuilt

from the cellar up; the builder said he believed its

foundation was no more than a piece of two-by-four.

The house also sits on clay and every now and again

there is major movement and a crack, enough to jolt

current owner, Neil MacKinnon, wide awake at night.

But these are never worth xing, according to Neil,

because eventually they always shift back.

There are now four bathroomsfor a long time there

was only oneand the kitchen has been modernised.

In one room, pictures of the MacKinnon forebears

hang. None of the heirs has ever moved out of the

home unless they died, although Neil made a brief

exception to this when he leased Dalness for three

years to pursue business interests in the Bahamas.

These days he works in Sydney and commutes home

to Dalness on weekends, the 2000-hectare farm run

by a manager in his absence.

With its spectacular views across undulating hills,

its a piece of heaven to come home to after the hustle

and bustle of Sydney, and that sense is enhanced by

the fact that Dalness has always been considered a

comfortable home rather than a stately treasure.

64 | 65

66 | 67

68 | 69

Barbara Fields mother couldnt believe it when she

found out Barbara was moving straight into the big

house at Douglas Park upon her marriage to Robert

Jones.

You cant even keep your bedroom tidy, Mrs Field

said to the twenty-three-year-old who was about to

become the lady of a manor with seven bedrooms on

its second oor. And, said her mother, it was high

time she learned how to cook. If I can read, I can

cook, cant I? was this tomboys response.

Barbara was not the slightest bit overawed by her

impending move from a small family home, built

after World War I when materials were in extremely

short supply, to a mansion that at one time was

pictured on Tattersalls lottery tickets.

Douglas Park was built for retired army doctor

Temple Pearson, who arrived in Hobart from Douglas,

Scotland, in 1822 with 1300 pounds in goods and

cash and his second wife, who some have claimed was

the half-sister of navigator Matthew Flinders. They

lived in a weatherboard cottage on the property while

he practised medicine locally, completing construc-

tion of the main residence in the mid 1830s, just a few

years before his death.

Douglas Park is a two-storey home with a faade

and stately portico made of sandstone from nearby

Ross in the Central Midlands. The porticos entab-

lature details the Pearson family coat of arms and

motto, Dum spiro, spero, or While I breathe, I hope.

It is believed that master Irish stonemason Hugh

Kean designed and built Douglas Park. His Ionic

columns were complete with entasis, a slight curvature

at the base of columns to prevent the optical illusion

of concavity, used in ancient times by the Greeks.

Extravagant cedar replicas of the front portico and

columns frame every door to the rooms off the front

entry foyer.

It is thought that Kean also designed two hotels

in Campbell Town, as all three buildings feature

handcarved sandstone staircases that are something

Douglas Park

70 | 71

of an engineering and architectural feat. At Douglas

Park a single piece of cantilevered sandstone connects

the landing on the staircase to the second oor. With

no supports, it is interlocked into the wall to stay put,

and boasts cast-iron balusters.

The stairswhich over the years have been painted

lettuce green and brown, and have now been taken

back to their original sandstone colourlead to the

bedrooms (one of which was being used to store chaff

before Robert Jones grandfather bought the house).

Young boys have been known to slide down the

handrail after rst learning to walk up the steps, while

girls have loved gliding down the stairs in all fashion

of gowns. Friends and family members also remember

gathering on the stairs to watch movies.

When Barbara moved in, the entire stone wall on

the right side of the house was sinking badly and had

a number of gaping holes. Campbell Town man Jack

Lockett and his team of skilled tradesmen found the

burst pipe to blame and repaired the house perfectly;

they also replaced the mortar in the chimneys and

repaired the stone wall enclosing the courtyard. The

Jones family credits Jack and his team with the

maintenance of Douglas Park and numerous iconic

Campbell Town buildings.

Temple Pearson didnt have any children, and when

he died in 1839, aged forty-nine, the place was left to

his brother, John, of Bathgate, Scotland. In 1846 John

Pearson put Douglas Park on the market and it was

leased by various people until purchased by A.E.

Jones, grandfather of Robert, in 1912.

At the moment, Barbara is busy restoring a room at

the front of the house. Knowing how to read was suf-

cient for learning to cook, and she still plays tennis

with her grandson (in her gumboots) on the court

that was once a hub of Campbell Town social life.

72 | 73

74 | 75

76 | 77

The country at Dunedin, near Launceston, isnt

arable. Its so rough that mustering of cattle and sheep

still takes place on horseback, and the back run of the

farm is so rocky that its known as the goat hills.

Which only makes the hectare of gardens this

property is renowned for all the more remarkable.

For Annabel Scott, who moved to Dunedin as a

young married woman in the 1970s, gardening has

become an addiction. With every year her garden

beds have become bigger and better, more diverse, a

different colour or style. Gardening gets her up at

5.30 am every day to start the watering, and she is still

toiling away in the evening.

The Scotts Gothic revival home is always adorned

with freshly picked posies (visitors clamour for the

rare breeds raised in her potting shed) and there is

homemade, garden-grown elderberry Sambucus wine

or syrup on stand-by, should guests pop in.

International and national garden tours often

include Dunedin in their itineraries, if they are lucky

enough to be allowed in. A proper tour of the

botanical extravaganza that wraps right around the

nineteenth-century homestead takes a good two

hours.

From the main driveway entrance stretches a bog

garden. Here, among the rst spectacles are the

dramatic Gunnera tinctoria and Gunnera manicata.

These giant herbaceous owering plants, native to

South America, have leaves that grow up to two

metres long, resemble giant rhubarb and produce

large owering seed heads that resemble corncobs

and can weigh up to ve kilograms.

Below them purple irises bloom, as do Peltiphyllum

peltatum, also known as Darmera peltata or umbrella

plants. These too thrive in a bog garden environment,

growing up to two metres tall and producing bold

rugose, or rounded, foliage. The dense, rounded ower

heads of white to pink appear in spring.

The cool and wet climate theme continues past

Dicksonia antarctica, a handsome Australian native

Dunedin

78 | 79

tree fern that can reach heights of six metres, and

which here towers over roses and the dainty green

bells of Nicotiana langsdori (owering tobacco),

contrasted with blazing blue delphiniums.

Saunter on past striking Papaver somniferum, or

opium poppy. Their fragile pink petals last just a few

days, but the glaucous blue pods persist. Providing

shade and perfume to the garden tapestry from above

is a Catalpa bignonioides, or the Indian bean tree.

This may reach heights of up to 25 metres and can be

recognised by its large, heart-shaped leaves, white

owers and the (inedible) fruit it produces that

resembles slender bean pods.

Other trees throughout the garden, all planted by

Annabel, include the smaller Styrax japonica, or

Japanese snowbell, which produces pendulous white

owers in summer. Then there is a Manglietia insignis,

or red lotus, an evergreen tree from China aligned to

the magnolia. It produces glossy twenty-centimetre

long leaves and fragrant, white magnolia-like owers

in spring. Maple crimson kings line the western side

of the Dunedin homestead, their dark crimson leaves

deepening to blood-red in summer. There are smaller

Eucryphia or leatherwood trees, a Liriodendron or

tulip tree, a white owering chestnut Aesculus, a forest

pansy Cercis canadensis, and ve different types of

elderberry Sambucus.

It was with a few trees that this novice gardener

started out in the 1970s. At the time, the garden at

Dunedin was nothing but a bare paddock surrounded

by an old lambertiana hedge, a pin oak and a few elm

trees, and twenty-eight depressing macrocarpa pines

that were pulled down.

The soil was abysmal and, before anything could be

planted, the ground had to be poisoned to eliminate

all the twitch and grass. So Annabel mapped out her

proposed beds with garden hoses, and sprayed the

ground within.

Next came mulch. The rst layer of this was the old

navy carpet that Annabel ripped out of the homestead,

the second was old jumpers and other clothes. Manure

from the shearing shed was piled on top, then

newspapers, and lots of pea straw.

Mulch and water, says Annabel, are critical to any

gardens success.

As she started to ll in the garden beds she had

created, Annabel joined all manner of gardening

groups such as the Heritage Rose Society, the Royal

Horticultural Society of England and the US Rock

Garden Society, through which seeds and plants were

bought by subscription. The Heritage Rose Society

alone was the source of 150 different roses.

From there developed an interest in perennials,

such as Eremurus, or foxtail lily. Their tall spikes add

height and colour, and many different varieties are

grown in this garden.

As the trees grew over the years, more woodland

plants were added to take advantage of the shade.

Annabel grows many different type of Hostas, plants

native to the Far East, most species occurring in the

damp woodland areas of Japan, and propagates any

number of Trillium.

She loves the diversity provided by magnicent

foliage, particularly variegated leaves that can lift any

dark spot. Some favourites are the rare variegated

Canna, the Bengal tiger, and the Armoracia rusticana

variegata, or variegated horseradish, both imported

from America.

Twenty varieties of ornamental grasses can be

found in the Dunedin gardens, including: Miscanthus

sacchariorus, which can grow two to three metres in

a year and forms a wonderful windbreak or screen;

Miscanthus variegatus, a variegated grass; and Stipa

gigantea, a glorious semi-evergreen grass that can

grow to about two metres in height and is adorned

with oat-like inorescences above graceful fountains

of foliage.

Other not-your-average-garden plants include: Sym-

phytum uplandicum, or Russian comfrey; Watsonia

ardernei, or bugle lily, a native of South Africa;

80 | 81

Brugmansia, or angels trumpet, with small trumpet-

shaped owers, native to South America; and the

spectacular golden owers of Ranunculus cortusiora.

The picking beds boast peonies and climbing sweet

peas, to name just a few. Adorning other areas are

dahlias, pink lilium, salvias, many different varieties

of foxgloves, climbing clematis and a rare Clematis

Florida Sieboldii from Japan, owering Heucheras,

and wispy blue Nepeta subsessilis.

Sisyrinchium striatum, or satin ower, is old-

fashioned but handy, as it will seed itself, and then

there are Philadelphus, or mock orange, hybrid

Moyesii Geranium roses, bred at the Royal Horti-

cultural Societys home of Wisley, Surrey, in 1938,

and hydrangeas from the famous US plant hunter

Dan Hinkley.

A beautiful paved part of the garden features a

sandstone statue carved by Daniel Herbert, of Ross

Bridge fame, and there are two other statues, Poppy,

who stands ensconced in variegated deutzia, and Pan.

Annabels advice is to go with one or two beautiful

statuesthats all you need.

Theres also a tranquil sh pond, lined with lilies

and boasting a small frog water fountain.

While most of the time shes slaving away keeping

the gardens weed-free, dynamic and recharged, the

garden has relaxation areas for all occasions, and

thats a favoured pastime too.

Annabel had never gardened before she moved to

Dunedin as a young married woman from Hobart

the blind date with Angus Scott arranged by her

friends had gone exceptionally well.

They moved into the old homestead, but it was in

poor shape, having been deserted for twelve years. Its

aesthetics also were not enhanced by the two-storey

enclosed verandah that had been tacked onto the

front of the home some decades earlier. Annabel and

Angus pulled it down and, to their delight, discovered

it had been built entirely of top-quality Huon pine.

This they used to furnish a new sunroom, and create

benchtops and cupboards for the renovated kitchen.

There were six layers of wallpaper that had to be

removed from the living areas and the woodwork was

stained. The place was so lled with silversh that one

night, not long after she moved in, Annabel had a

dream they had eaten the entire staircase.

But the homestead was gradually restored, as were

outbuildings: a beautiful old dairy was turned into an

ofce, and the stables still come in handy for the

horses needed to muster sheep and cattle on this

8000-hectare property.

Dunedin homestead was built in about 1858 to

replace an original home on the property that burned

down. Its owner was Captain Samuel Tulloch, originally

from the Shetland Islands. He ran away to sea at the

age of twelve, and eventually captained several ships,

including the Halcyon, which was a regular packet

between Launceston and Adelaide. His daughter Alice

married Robert Steele Scott, and one of their eight

children, Samuel Tulloch Scott, established himself as

a leading breeder of Aberdeen Angus cattle and Merino

sheep at Dunedin. Angus is Samuel Scotts grandson.

After Annabels day begins at 5.30 am with the

hoses being turned on, theres any number of tasks to

attend to, depending on the season, from policing the

weeds to pruning, mulching and fertilising. Its a

never-ending battle against thistle, oxalis, and native

animals, but Annabel has the upper hand.

In her potting houses, Annabel propagates rare and

unusual plants, transplanting them into the garden

when theyre established enough, or giving them away.

She describes herself as something of a frustrated

artist; the owers are her palette, and the garden her

continually evolving canvas.

Her three top tips for a successful garden are: doing

it for the love of it; focusing on health (of self and

plants); and ample quantities of water and mulch.

Annabels recipe for elderfower syrup

2 large lemons

30 elderower heads

2 ounces citric or tartaric acid

3 pounds sugar

3 pints boiling water

Slice lemons thinly. Place in a jug or large bowl with

the ower heads (including as little stalk as possible).

Sprinkle with citric acid and sugar and pour boiling

water over.

Cover with a lid and leave for three days in a cool place,

skimming daily. Then bottle ityou can freeze it too.

82 | 83

84 | 85

The decision to sell their famous family estate,

Kameruka, was gut-wrenching for Frank Foster and

his wife, Odile. It meant severing ties with more than

150 years of a Tooth dynasty tradition, about 4000

hectares of prized beef and dairy country on the New

South Wales south coast, an 1834 verandah-lined

homestead and gardens that were a six-time winner

of the Sydney Morning Herald garden competition.

But it also led the couple to Egleston, near Campbell

Town in the Central Midlands, and they still cant

believe their luck.

They are now the proud custodians of a stunningly

restored Georgian mansion that is steeped in history,

with gently sloping gardens above river ats that

would bring a tear to any former dairy farmers eye,

and it is all just one hours drive away from the trout-

shing heaven of the Central Highlands.