Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Simmen

Uploaded by

Zee De Vera LaderasCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Simmen

Uploaded by

Zee De Vera LaderasCopyright:

Available Formats

Rhinology, 44, 98-101, 2006

*Received for publication: November 21, 2005; accepted: January 28, 2006

INTRODUCTION

Olfaction disorders are often not taken seriously because they

are viewed as affecting the lower senses those involved

with the emotional life instead of the higher senses that

serve the intellect

(1)

. Sense of smell? . I never gave it a

thought - you dont normally give it a thought but when you

loose it it is like being struck blind or deaf. Anosmia may not

be the disaster in humans that it would be for the majority of

the animals but we must realize that it can be a very traumatic

condition with a profound impact on our social life

(2)

. Smell is

a sense whose value seems to be only appreciated after it is

lost. The sense of smell also plays an important role in our

interaction with the environment and therefore it can have a

direct influence on human behaviour

(3)

and can lead to a sig-

nificant decrease in quality of life. In evaluating a patient who

may have a possible olfactory disorder - hyposmia, the clini-

cian has several tools at his disposal. The patients history,

physical exam and olfactory testing as well as testing the taste

are all relevant. With this, most of the information for the eti-

ology of the possible hyposmia can be obtained. Furthermore

blood tests and diagnostic radiology have an important role in

the diagnosis of a smell disorder.

Since the sense of olfaction can differentiate between thou-

sands of different odorants, it is impossible to assess the whole

sensory system with a few simple tests. Depending on the

information that is needed, specific tests can be used to mea-

sure certain facets of the olfactory system. In rhinology, the

quantitative assessment of smell is important because hypos-

mia or anosmia due to conductive olfactory loss is a frequent

symptom of rhinological diseases such as allergic rhinitis or

chronic rhinosinusitis

(4-8)

. Qualitative disorders, the so-called

dysosmias (for example cacosmia or parosmia), are much more

difficult to measure. Nevertheless, specific tests for the assess-

ment of qualitative disorders have also been developed.

As in audiology, most tests are dependent on patient compli-

ance (subjective methods). For the assessment of the non-

compliant patients and for scientific research, objective test

methods are needed. These commonly measure changes in the

central nervous system provoked by olfactory stimulants.

CLINICAL OLFACTORY TESTING

Taste and Smell

Taste and smell are independent but it is often difficult to split

between them with the patients history alone. Patients with

smell and/or taste deficits initially often complain of gustatory

problems. For example, after a head injury a patient might

report that a favorite tomato sauce no longer "tastes" right.

However, rather than experiencing a problem with taste per se,

this patient is more likely experiencing an alteration in flavor

perception.

Because pure taste disorders are very rare, a simple taste test

can be performed beforehand to rule out this specific diagno-

Olfactory disorders frequently occur in rhinological disease. Different subjective and objective

test methods are available to assess the sense of olfaction. Among the subjective methods,

screening tests and threshold measurements are commonly used to quantify hyposmia or

anosmia. Qualitative methods are available using discrimination and identification tests.

Objective methods are used in research and in some medicolegal situations. Objective tests

include olfactory evoked potentials, functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and functional

Positron Emission Tomography.

The measurement of the sense of smell helps to assess the whole spectrum of the effects of

nasal disease. This is especially important before rhinological surgery, because a non-detect-

ed smell disorder in patients with rhinological disease is common. The assessment of a pre-

existing hyposmia or anosmia helps to avoid a postoperative claim that this was caused by

surgery. A variety of validated screening tests for olfaction is available and they are a useful

tool to document whether a patient is able to smell.

Key words: anosmia, assessment of olfaction, hyposmia, sense of smell, sinus surgery,

threshold level

SUMMARY

Olfaction in rhinology methods of assessing the

sense of smell*

Daniel Simmen and Hans Rudolf Briner

ORL-Zentrum, The Hirslanden Clinic, Zurich, Switzerland

REVIEW

Methods of assessing olfaction 99

sis. By the use of liquids that stimulate the sense of taste for

salty, sweet, sour and bitter flavours a patients inability to

detect one or more flavours is identified. Loss or impairment

of taste can occur in various degrees (Table 1).

Subjective test methods

Subjective test methods are frequently used to assess olfaction

because they can be done quickly and easily in a compliant

patient. Several simple chemosensory tests can be done in the

primary care office, but in a specialized ENT setup today a val-

idated screening test with a printed form for documentation

should be used at all cost. In the last decade a few validated

screening test for olfaction have been developed worldwide

and they can be used with the physician or self-administered

by the patient alone. To obtain an overview of the many differ-

ent tests available, three different categories can be defined

(Table 2).

Screening tests of olfaction are designed to detect whether a

patient has an impaired sense of smell or not. These tests

should be fast, reliable and cheap. A commonly known exam-

ple is a serie of bottles containing a certain odorant such as

coffee, chocolate or perfume to investigate a simple overview.

Also each nostril should be tested separately to ascertain

whether the problem is unilateral or bilateral lateralized

screening.

In recent years, more sophisticated tests have been developed

that are both reliable and convenient to use

(4)

. The University

of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) or Smell

Identification Test

TM

(Sensonics, Inc., P.O. Box 112, Haddon

Heights, NJ 08035-0112 USA) is a well-known example. It is a

scratch and sniff test with microencapsulated odorants, which

is frequently used in the United States

(9)

. Other examples are

the 12-item Brief Smell Identification Test

TM

(Sensonics,

Inc., P.O. Box 112, Haddon Heights, NJ 08035-0112 USA

(10)

,

the Japanese odor stick identification test (OSIT

(11)

), the

Scandinavian Odor Identification Test (SOIT,

(12)

), and the

Smell Diskettes for the screening of olfaction (Novimed,

Heimstrasse 46, CH-8953 Dietikon, Switzerland). This test pre-

sents 8 odorants in reusable diskettes to the patient (Figure 1)

and has also a pictorial representation in a forced multiple-

choice manner

(13)

. Another example is the SniffinSticks test

using a pen-like device for odor identification

(14)

and finally the

latest example a brief three-item smell identification test

(15)

that is validated and highly sensitive in identifying olfactory

loss in patients with chemosensory complaints.

All the listed test batteries are validated (some with cultural

bias) and well documented in the literature and therefore best

used today for the first investigation of an olfactory disorder or

to document the olfactory function before any kind of nasal

surgery. However, with the screening tests one can only distin-

guish between normal and abnormal smell function. For the

further evaluation of a smell dysfunction (Table 2) a quantita-

tive investigation is needed.

Quantitative olfaction tests measure the threshold levels of cer-

tain odorants in order to quantify an impaired sense of smell.

They are usually more time consuming to perform but are use-

ful to monitor the degree of hyposmia. However, they are

unable to determine the cause and provide prognostic informa-

tion or therapeutic guidance.

Table 1. Types of taste impairment.

Hypogeusia diminished taste

Dysgeusia distorted taste

Aligeusia alterered taste

Phantogeusia persistent abnormal taste

Ageusia total loss of taste

Table 2. Subjective test methods to assess the sense of smell.

Test method Definition

Screening tests of olfaction Fast evaluation whether or not there

is a smell disorder

Quantitative olfaction tests Tests to quantify an existing smell

disorder (Threshold measurement)

Qualitative olfaction tests Evaluation of qualitative smell

disorders

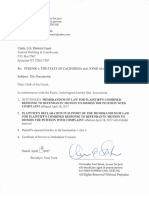

Figure 1. Screening test of olfaction: Smell Diskettes.

100 Simmen and Briner

There are many threshold tests available today, most of them

using n-butanol as the odorant. The object is to find the weak-

est concentration of n-butanol that the patient can detect, start-

ing with the weakest dilution. Examples of such extended test

kits are the Connecticut Test -CCCRC threshold test

(16)

, and

the Sniffin Sticks

threshold test (Burghart Medizintechnik,

Tinsdaler Weg 175, 22880 Wedel, Germany)

(14)

. The European

test of olfactory capabilities - ETOC, a well cross-culturally val-

idated test

(17)

and the Smell Threshold Test

TM

(Sensonics,

Inc., P.O. Box 112, Haddon Heights, NJ 08035-0112 USA)

measure the threshold of phenyl-ethyl-alcohol

(18)

.

These tests measure the olfactory performance and separate

anosmics and normosmics and allow an assessment of hypos-

mia. For every test a different scoring system is used to deter-

mine the grade of hyposmia (mild, moderate and severe

hyposmia, anosmia).

Another very accurate way of measuring smell thresholds can

be done with olfactometers; these machines are designed to

present precise concentrations of odorants. An example of an

olfactometer that is used to measure the threshold level of

vanilla is shown in Figure 2. Just as an audiogram is used to

measure the hearing level, this computer-linked device is

designed to measure the olfactory threshold for both sides sep-

arately. Up till now threshold olfactometers are mainly used in

research projects and are not yet available for office use.

Nevertheless these tests all have their limitations, especially

when investigating children, people with cognitive impairment

or people from different cultural backgrounds. The complexity

of some tests, the price for extended smell-kits for threshold

measurement and the time-consuming factor deter many doc-

tors from starting to evaluate adequately this specific group of

patients and this is therefore still concentrated in specialized

centres.

Qualitative tests of olfaction are used to assess a wide range of

qualitative smell disorders. These so-called dysosmias are

difficult to measure because patients with dysosmias find it dif-

ficult to describe their altered sense of smell. Nevertheless,

specific tests have been designed to assess some of these quali-

tative disorders. The ability to recognize certain odorants can

be measured by identification tests, and discrimination tests

assess the ability to distinguish between different odors. An

example of such a test is the already above mentioned Sniffin

Sticks

extended test battery which combines quantitative

and qualitative measurement

(19,20)

.

Trigeminal nerve assessment

In addition to olfactory epithelium the nasal mucosa also con-

tains trigeminal nerve endings. They are important in detecting

tactile pressure, pain and temperature sensation. Using special

odorants with a trigeminal component such as mustard, men-

thol, capsaicin, vinegar and onion the function can be assessed.

Objective test methods

The objective measurement of the sense of smell is difficult

and relies on detecting changes in the central nervous system

provoked by olfactory stimulants. It is the only way to assess

olfaction in non-compliant patients or malingerers. A well-

established method is the olfactory evoked potentials

(14,21,22)

.

New techniques include functional imaging (functional

Magnetic Resonance Imaging, functional Positron Emission

Tomography) which allow the direct visualization of central

changes caused by olfactory stimulants. These methods are

currently used for scientific research but have the potential to

become tools also for clinical routine.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Based on current reports, 1 to 2 percent of the american popu-

lation below the age of 65 experience an impaired smell to a

Table 3. Types of smell impairment

(24)

.

A: Quantitative olfactory dysfunction.

Normosmia normal sense of smell

Hyposmia diminished sense of smell

Hyperosmia enhanced odor sensitivity

Anosmia total loss of smell

Specific Anosmia inability to perceive a certain odor

B: Qualitative olfactory dysfunction.

Dysasmia distorted detection of smell

Parosmia perversion of the sense of smell

Carosmia inappropriate detection as foul or unpleasant

Phantosmia hallucination of smell

Heterosmia inappropriate distinction between odours

Figure 2. Measurement of the threshold level of vanilla with an olfac-

tometer.

significant degree and out of this population more than 200.000

people visit a physician each year to help with smell disorder

and related problems (Statistics on Smell, National Institute of

Health, 2005). This illustrates the importance of the adequate

assessment of smell including the use of smell tests.

Smell disorders are a common finding in patients with rhino-

logical disease

(4)

. The measurement of the sense of smell

helps to assess the whole spectrum of the effects of nasal dis-

ease. This is especially important before rhinological surgery,

because a non-detected smell disorder may lead to the accusa-

tion that impaired olfaction may have been caused by surgery.

In a study of patients prior to nasal surgery, 10.3% of patients

had an altered sense of smell making it desirable that this is

documented in order to avoid postoperative claims that this

was caused by surgery

(23)

. Routine preoperative smell tests are

therefore an essential step to avoid a postoperative claim that

surgery has been responsible for a pre-existing olfactory disor-

der.

Smell tests also help to provide comparable data in studies to

audit the outcome of the treatment of nasal disease. Smell

tests also help to focus both the patients and the surgeons

attention to this aspect of their disease so that it has not been

forgotten until it is too late! As we still dont know exactly

where we have olfactory epithelium in the nasal mucosa and

which areas are therefore at most risk during sinus surgery, the

pre- and postoperative workup of the sense of smell is essential

to find out how to tailor the surgery to preserve the sense of

smell at all cost. The documentation of the smell function over

time is also an essential point in the management of the med-

ical treatment as the impairment of smell might be the first

sign of a recurrence of the nasal disease and helps to motivate

the patient to accept medical treatment in long term.

REFERENCES

1. Schiffman SS. Tate and smell disorders in disease. N Engl J Med

1983; 308, 1275-1280.

2. Van Toller S. Assessing the Impact of Anosmia: Review of a

Questionnaires Finding. Chem. Senses 1999; 24: 705-712.

3. Estrem SA, Renner G. Disorders of Smell and Taste. Otolaryngol

Clin North Am 1987; 20: 133-147.

4. Fokkens W, Lund V, et al. European Position Paper on

Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyposis, Rhinology 2005; Suppl 18.

5. Golding-Wood DG, Holmstrom M, Scadding GK, Lund VJ. The

treatment of hyposmia with intranasal steroids. J Laryngol Otol

1996; 110: 132-135.

6. Ikeda K, Sakurada T, Suzaki Y, Takasaka T. Efficacy of systemic

corticosteroid treatment for anosmia with nasal and paranasal

sinus disease. Rhinology 1995; 33: 162-165.

7. Jankowski R, Bodino C. Evolution of symptoms associated to

nasal polyposis following oral steroids treatment and nasalisation

of the ethmoid. Rhinology 2003; 41: 211-219.

8. Seiden AM, Duncan J. The Diagnosis of a Conductive Olfactory

Loss. Laryngoscope 2001; 111: 9-14.

9. Doty RL, Shaman P, Kimmelman CP, Dann MS. University of

Pennsylvania smell identification test: A rapid quantitative olfacto-

ry function test for the clinic. Laryngoscope 1984; 94: 176-178.

10. Doty RL, Marcus A, Lee WW. Development of the 12-item Cross-

Cultural Smell Identification Test (CC-SIT). Laryngoscope 1996;

106: 353-356.

11. Hashimoto Y, Fukazawa K. et al. Usefulness of the odor stick

identification test for Japanese patients with olfactory dysfunction.

Chem Senses 2004; 29: 565-571.

12. Nordin S, Nyroos M. et al. Applicability of the Scandinavian Odor

Identification Test: a Finnish-Swedish comparison. Acta

Otolaryngol 2002; 122: 294-297.

13. Briner HR, Simmen D. Smell Diskettes as Screening Test of

Olfaction. Rhinology 1999; 37: 145-148.

14. Kobal G, Hummel T. Olfactory evoked potentials in humans. In:

Getchell TV, 1991.

15. Jackman A, Doty R. Utility of a Three-item Smell identification

Test in Detecting Olfactory Dysfunction. Laryngoscope 2005; 115:

2209-2212.

16. Cain WS, Goodspeed RB, Gent JF, Leonard G. Evaluation of

olfactory dysfunction in the Connecticut Chemosensory Clinical

Research Center. Laryngoscope 1998; 98: 83-88.

17. Thomas-Danguin T, Rouby C, et al. Development of the ETOC: a

European test of olfactory capabilities. Rhinology 2003; 41: 142-

151.

18. Pierce JD, Doty RL, Amore JE. Analysis of position of trial

sequence and type of diluent on the detection threshold for

phenyl ethyl alcohol using a single staircase method. Percept

Motor Skills 1996; 82: 451-458.

19. Hummel T, Sekinger B, Wolf SR, Pauli E, Kobal G. Sniffin

Sticks: olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of

odor identification, odor discrimination and olfactory threshold.

Chem Senses 1997; 22: 39-52.

20. Wolfensberger M, Schnieper I, Welge-Lssen A. SniffinSticks:

a New Olfactory Test Battery. Acta Otolaryngol 2000; 120: 303-306.

21. Auffermann H, Mathe F, Gerull G, Mrowinski D. Olfactory

evoked potentials and contingent negative variation simultaneous-

ly recorded for diagnosis of smell disorders. Ann Otol Rhinol

Laryngol 1993; 102: 6-10.

22. Kobal G, Hummel T, Sekinger B, Barz S, Roscher S, Wolf S.

Sniffin Sticks: screening of olfactory performance. Rhinology

1996; 34: 222-226.

23. Briner HR, Simmen D, Jones N. Impaired sense of smell in

patients with nasal surgery. Clin Otolaryngol 2003; 28: 417-419.

24. Jones NS, Rog D. Olfaction: a review. JLO 1998; 112: 11-24.

Daniel B. Simmen, MD

ORL-Zentrum

Klinik Hirslanden

Witellikerstrasse 40

8032 Zrich

Switzerland

Tel: +41-1-387-2800

Fax: +41-1-387-2802

E-mail: simmen@orl-zentrum.com

Methods of assessing olfaction 101

You might also like

- SampleDocument2 pagesSampleZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- Skype 4085153108 250 SQM Citiland Langkaan2, Dasma, Cavite For A Small Backyard Pool Sir Design and MaterialsDocument1 pageSkype 4085153108 250 SQM Citiland Langkaan2, Dasma, Cavite For A Small Backyard Pool Sir Design and MaterialsZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- Company Profile EditedDocument17 pagesCompany Profile EditedZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- October 25, 2017 - : Pool QuotationDocument2 pagesOctober 25, 2017 - : Pool QuotationZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- ValDocument1 pageValZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- January 20, 2018 Mr. Edgar Espiritu Ilocos Sur: Pool ContractDocument2 pagesJanuary 20, 2018 Mr. Edgar Espiritu Ilocos Sur: Pool ContractZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- Backwash Valve - These Come in Two Types:: When Ordering Your Warranty, How Do You Ensure Pool Coverage?Document2 pagesBackwash Valve - These Come in Two Types:: When Ordering Your Warranty, How Do You Ensure Pool Coverage?Zee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- 4X8 @17K PSQM Quotation, Inclusions and Designs Mode of PaymentDocument1 page4X8 @17K PSQM Quotation, Inclusions and Designs Mode of PaymentZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- All ExistenceDocument23 pagesAll ExistenceAshwin PanditNo ratings yet

- Proposal AlfonsoDocument2 pagesProposal AlfonsoZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- Dspcs Company ProfileDocument16 pagesDspcs Company ProfileZee De Vera Laderas100% (1)

- Swimming Pool Construction Services: Project Client Location SubjectDocument2 pagesSwimming Pool Construction Services: Project Client Location SubjectZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- Sewerage and Drainage Layout: Ground Floor Second Floor Roof DeckDocument1 pageSewerage and Drainage Layout: Ground Floor Second Floor Roof DeckZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- Quotation 40sqm W JacuzziDocument3 pagesQuotation 40sqm W JacuzziZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- Asean IntegrationDocument27 pagesAsean IntegrationZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- Finals Exam Part 1 (Theories)Document7 pagesFinals Exam Part 1 (Theories)Zee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- 3rd EyeDocument1 page3rd EyeZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- Quotation 40sqm W JacuzziDocument3 pagesQuotation 40sqm W JacuzziZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- Infinity Pool DetailsDocument1 pageInfinity Pool DetailsZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- Request Letter Conduct SurveyDocument2 pagesRequest Letter Conduct SurveyZee De Vera Laderas83% (12)

- 33 Odor BasicsDocument16 pages33 Odor BasicsjaviercdeaeNo ratings yet

- Activities: Manila Central University College of Computer StudiesDocument1 pageActivities: Manila Central University College of Computer StudiesZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- Guide DocumentationDocument13 pagesGuide DocumentationZee De Vera LaderasNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Robbie Hemingway - Text God VIP EbookDocument56 pagesRobbie Hemingway - Text God VIP EbookKylee0% (1)

- Saes T 883Document13 pagesSaes T 883luke luckyNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Write-UpDocument4 pagesPortfolio Write-UpJonFromingsNo ratings yet

- IBS and SIBO Differential Diagnosis, SiebeckerDocument1 pageIBS and SIBO Differential Diagnosis, SiebeckerKrishna DasNo ratings yet

- PBPO008E FrontmatterDocument13 pagesPBPO008E FrontmatterParameswararao Billa67% (3)

- Npad PGP2017-19Document3 pagesNpad PGP2017-19Nikhil BhattNo ratings yet

- Model Contract FreelanceDocument3 pagesModel Contract FreelancemarcosfreyervinnorskNo ratings yet

- CCNP SWITCH 300-115 - Outline of The Official Study GuideDocument31 pagesCCNP SWITCH 300-115 - Outline of The Official Study GuidehammiesinkNo ratings yet

- STRUNK V THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA Etal. NYND 16-cv-1496 (BKS / DJS) OSC WITH TRO Filed 12-15-2016 For 3 Judge Court Electoral College ChallengeDocument1,683 pagesSTRUNK V THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA Etal. NYND 16-cv-1496 (BKS / DJS) OSC WITH TRO Filed 12-15-2016 For 3 Judge Court Electoral College ChallengeChristopher Earl Strunk100% (1)

- AT10 Meat Tech 1Document20 pagesAT10 Meat Tech 1Reubal Jr Orquin Reynaldo100% (1)

- CBSE Class 10 Science Sample Paper SA 2 Set 1Document5 pagesCBSE Class 10 Science Sample Paper SA 2 Set 1Sidharth SabharwalNo ratings yet

- Financial Statement AnalysisDocument18 pagesFinancial Statement AnalysisAbdul MajeedNo ratings yet

- Ajsl DecisionMakingModel4RoRoDocument11 pagesAjsl DecisionMakingModel4RoRolesta putriNo ratings yet

- ERP22006Document1 pageERP22006Ady Surya LesmanaNo ratings yet

- Case Study Analysis - WeWorkDocument8 pagesCase Study Analysis - WeWorkHervé Kubwimana50% (2)

- Resolution: Owner/Operator, DocketedDocument4 pagesResolution: Owner/Operator, DocketedDonna Grace Guyo100% (1)

- Crown BeverageDocument13 pagesCrown BeverageMoniruzzaman JurorNo ratings yet

- Technical and Business WritingDocument3 pagesTechnical and Business WritingMuhammad FaisalNo ratings yet

- Intertext: HypertextDocument8 pagesIntertext: HypertextRaihana MacabandingNo ratings yet

- Capital Structure and Leverage: Multiple Choice: ConceptualDocument53 pagesCapital Structure and Leverage: Multiple Choice: ConceptualArya StarkNo ratings yet

- Exploded Views and Parts List: 6-1 Indoor UnitDocument11 pagesExploded Views and Parts List: 6-1 Indoor UnitandreiionNo ratings yet

- Bloomsbury Fashion Central - Designing Children's WearDocument16 pagesBloomsbury Fashion Central - Designing Children's WearANURAG JOSEPHNo ratings yet

- 2011 - Papanikolaou E. - Markatos N. - Int J Hydrogen EnergyDocument9 pages2011 - Papanikolaou E. - Markatos N. - Int J Hydrogen EnergyNMarkatosNo ratings yet

- BBO2020Document41 pagesBBO2020qiuNo ratings yet

- T Rex PumpDocument4 pagesT Rex PumpWong DaNo ratings yet

- Multi Core Architectures and ProgrammingDocument10 pagesMulti Core Architectures and ProgrammingRIYA GUPTANo ratings yet

- Knitting in Satellite AntennaDocument4 pagesKnitting in Satellite AntennaBhaswati PandaNo ratings yet

- Mehdi Semati - Media, Culture and Society in Iran - Living With Globalization and The Islamic State (Iranian Studies)Document294 pagesMehdi Semati - Media, Culture and Society in Iran - Living With Globalization and The Islamic State (Iranian Studies)Alexandra KoehlerNo ratings yet

- SLTMobitel AssignmentDocument3 pagesSLTMobitel AssignmentSupun ChandrakanthaNo ratings yet

- Onco Case StudyDocument2 pagesOnco Case StudyAllenNo ratings yet