Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Teaching of Thinking Using Philosophical Inquiry: Connie Chuen Ying YU

Uploaded by

dodoltala2003Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Teaching of Thinking Using Philosophical Inquiry: Connie Chuen Ying YU

Uploaded by

dodoltala2003Copyright:

Available Formats

The Teaching Of Thinking Using Philosophical Inquiry

Connie Chuen Ying YU

University of Melbourne

Teaching students thinking may bring improvement to school curricula, and enable

students to succeed in their studies and function as competent citizens in future. Researchers

highly recommend thinking skills instruction, using in-content or out-of-content programs.

Thinking skills are abilities of individuals to performmental actions and work on ideas externally

perceived or internally constructed in order to satisfy a goal. One in-content thinking skills

program- Philosophical Inquiry - is described in this paper and suggestions for implementation

are provided. This approach requires the building of a community of inquiry in the classroomand

skilful questioning. Despite the lack of teacher training and assessment tools, the teaching of

thinking may still be implemented successfully with the commitment of teachers, support from

school authorities, and participation in action research.

,

,

1. Introduction

Researchers recommend teaching of thinking in the school curricula, so that students

develop thinking skills - abilities of individuals to perform mental actions and work on

ideas externally perceived or internally constructed in order to satisfy a goal. These

mental actions include visualizing, modelling, idea organizing, categorizing, inferring,

transferring and problem solving (Bowden, 1986; Biggs & Telfer, 1987; Sternberg,

1987:252).

There are basically two different approaches in teaching thinking: in-content

(integrated into school subjects) and out-of-content (taught separately) approaches.

Teaching is focused on students thinking processes and learning how to learn is highly

valued. Students have been traditionally assessed by how much information or facts they

can reproduce in tests and examinations, but now there is a wide awareness that students

should be assessed by how well they perform.

In this paper, the background of the teaching of thinking is outlined from the

literature in only two aspects: pioneers works, and a thinking curriculum. Among

desirable programs studied, the author presents only one promising program -

Philosophical Inquiry within limited scope. This is an in-content approach of teaching

thinking skills through dialogues centred on philosophical issues which emerge from

texts or stories. It requires teachers to build a community of inquiry in the classroom

through skilful questioning, clear logical thinking and ideally training in teaching

children philosophy. Next the author states the problems that concern teaching of

thinking and finally gives suggestions for implementation.

2. Background To The Teaching Of Thinking

2A. Pioneers Works

Teaching students thinking has become a strong movement towards the end of the

twentieth century, as noted by Nisbet (1993) and Mulcahy et al. (1993). Previous

influential psychologists formulated theories and models of human nature based on their

research. Biggs and Telfer (1987) group these psychologists as (1) Behaviourists, who

concentrate on people as reacting to a highly structured environment; (2) Cognitivists,

who concentrate on people as thinkers and problem-solvers in an environment that

signals information to them; and (3) Humanists, who concentrate on how people feel

about themselves and their relationships with others. Educators may prefer one model or

another and they will implement their beliefs in educational practices. There is increasing

awareness of the need to teach students thinking in contemporary literature, showing

wide acceptance of the Cognitivists view.

The theories of constructivism and information processing have contributed to the

teaching of thinking. They reveal how our minds work, help teachers understand how

students learn and how they can plan more effective instruction. Piaget and Bruner were

major theorists in constructivism. Piaget studied the origins of cognition and explained

how children interact with the environment at different stages of cognitive development:

pre-operational, concrete operational, and formal operational. Bruner also described

stages of development and language being a tool of thought which is necessary for the

construction of meaning. Both theorists suggest that teachers should understand students

developmental stages and provide students opportunities to evaluate and give reasons for

what they say (OTuel & Bullard, 1995:9-12). Information processing theorists have

various ways of interpreting the learning sequence, but all their models consist of three

aspects: input, process and output. Both constructivism and information processing point

out learners needs of active participation in the teaching process in order to construct

knowledge for themselves, whereas telling students answers limit their understanding and

opportunities to find out for themselves. Process and not product is emphasised in

instruction and academic time should be spent more on higher levels of thinking (OTuel

& Bullard, 1995:17).

Among the pioneers, Nisbet (1993) reveals that Edward de Bono, being the most

well-known, founded the Cognitive Research Trust (CoRT) in 1969 and published

Teaching Thinking in 1976 which was later translated into 26 languages. The school

curriculum is overcrowded, according to de Bono (1991), and thinking skills taught are

confined to limited skills such as sorting, analysing and some debating skills. More

important higher order thinking skills like decision making, setting priorities, and

choosing alternatives are lacking. He stresses the great need to teach thinking skills in

schools, because thinking skills are life skills much needed by individuals in order to

operate effectively in an increasingly complex world. He advocates deliberate and direct

teaching of thinking skills, rather than infusing it into subjects.

Lipman (1985) points out that the traditional curriculum is fragmented, caused by

isolated subjects, and he argues for the inclusion of philosophy as a subject in the K-12

curricula. He believes that that the central objective of education is to create

communities of inquiry, through which children learn to value independent and

autonomous thinking rather than just helping children to acquire the knowledge that

adults possess (Lipman, 1985:106). He sees that the Philosophy for Children Program can

sharpen thinking skills and produce educationally significant results, and teaching

students philosophy can reduce their sense of fragmentation in the school curricula. His

view of teaching children philosophy as a way of teaching thinking is supported by Beyer

(1991:72-6) who believes that philosophy offers valuable perspective and adds unique

insights into cognitive processes. He argues that a thinking curriculum should attend to

the methods philosophers used to stimulate thinking, and the dispositions that motivate

thinking, and it will be worthwhile and effective in producing skilful thinkers. Schools

did not have formal instruction in thinking because educators wrongly believe that

students would acquire thinking skills automatically through subjects, and that average

students could not learn philosophy because it is regarded as an area taught in universities

only (Ruggiero, 1995:5-6).

Criticised by Kauchak and Eggen (1989:347), most classroom instruction is geared

to the teaching and learning of information and facts, much memorization in tests and

examinations, and low level of thinking. Students have been taught what to think, but

rarely on how to think. Paul (1994) criticised the present education for wrongly assuming

that students after learning information, concepts, and skills, will automatically replace

ignorance with knowledge, misconception with truth. Paul believes that students learn

through practice and not by teachers telling them what to believe and think about a

subject. Very often values and principles are often learned and memorized without real

understanding. He thinks what students really need is to learn by practice, think and try

out ideas learnt; and to see for themselves when they have succeeded, when they have

failed, and the differences between the successes and failures. Paul, Binker and Weil

(1993), and Paul et al. (1993) have developed handbooks for teachers to teach critical

thinking in order to equip students for the real world. They have developed thirty-five

strategies and instructional procedures to teach thinking through remodelling lesson plans,

and help teachers to develop for themselves thinking skills and ways of teaching their

students.

2B. A Thinking Curriculum

The inclusion of thinking skills instruction in the school curriculum has now gained

wide support, and the teaching of thinking is happening in several countries (De Bono,

1991). The positive effect of teaching thinking/learning strategies in research has led to

the development of its inclusion in content instruction (e.g. Husen & Postlethwaite, 1992;

Mulcahy et al., 1993; Gredler, 1992:137-8). Some facts that call for thinking skills

instruction are pointed out by Resnick and Resnick:

Today society requires individuals to be not only literate, but also able to analyse

information, draw conclusions, generate hypotheses, and find solutions.

Students are now facing the challenges of information explosion, obsolescence of

much past information, and multiple changes at present and in the future.

Advocates regard the process of learning as being just as important as the product

(cited in OTuel & Bullard, 1995:2).

To find out the effectiveness of thinking skills programs and their suitability for

different age groups, Mulcahy et al. (1993) experimented with both approaches.

Feuerstein Instrumental Enrichment (IE) was taught outside curricular content (out-of-

content), and the Strategies Program for Effective Learning/Thinking (SPELT) was

taught with curricular content (in-content). The teachers assigned to teach the two

programs were given intensive in-service training beforehand. It was ensured that they

acquired the necessary teaching skills and strategies. The training of teachers was

extended through continued coaching by consultants and peers both in and out of the

classroom situation. Research findings indicated that cognitive education was effective in

improving student thinking. The SPELT program tended to produce more positive

changes in students overall performance. Even after two years of instruction in the two

cognitive education programs, the students comprehensive monitoring skills were

observed to be generally better than their control counterparts. Therefore Mulcahy et al.

(1993), urged that teaching learning/thinking skills should be incorporated in the school

curriculum, using either out-of-content or in-content approach. Parents, teachers and

administrators involved with their studies were also in favour of thinking skills

instruction.

School administrators and policy makers are urged by researchers to include thinking

skills instruction in the school curriculum and to legitimize the time for teaching thinking

skills (e.g. De Bono, 1991). Though they may not be able to schedule time for an out-of-

content program, they may use in-content programs. Meanwhile teachers may still build

up their repertoire and use various techniques to help students develop higher order

thinking skills (e.g. Kauchak & Eggen, 1989; Gredler, 1992; Mulcahy et al., 1993):

In the classroom, teachers use thinking aloud, which is describing thoughts

verbally so that their thoughts and thinking skills can be made known to the

students.

Include reflection in teachers professional development programs.

Provide regular time for students to reflect and teach them to value ways of

thinking used by the others.

Help students to generalize and transfer by relating the thinking skills already

learnt to the new context or situation.

Encourage students to think of possible applications of a learned skill.

Show support and encouragement to a child or the class in thinking exploration.

Teachers act as coaches or facilitators in helping students to think.

Provide language form for young students to express their thoughts or help them

to express their thoughts through drawings or role-playing.

Provide opportunities for students to work together and discuss, share, trial and

evaluate their skills.

Group work and discussion are effective means to develop students thinking

skills.

Parents are recommended to help their children by demonstrating their models of

thinking skills to their children and encouraging them in the development of this

aspect.

Teachers or instructors may develop their own thinking abilities and be able to teach

thinking through reading references such as Ruggieros (1995) popular book, The Art of

Thinking. Paul et al. (1993:37-9) suggest teachers to think beyond the limit of subject

matter, and create an environment which values truth, openmindedness, empathy,

autonomy, rationality and self-criticism. They state that students need to ask questions to

probe meanings, request reasons and evidence, facilitate elaboration, keep discussions

from becoming confusing, highlight contradictions and inconsistencies, and elicit

implications and consequences. Eventually students can learn to believe in the power of

their own minds, to identify and solve problems.

The commitment to improve thinking skills brings the needs to evaluate those skills,

according to Baron (1987:221-44). Administrators want to see whether the effect of

thinking skills programs and professional development activities justify the efforts.

Program developers and researchers want to find out the validity and impact of thinking

skills instruction on students. Through evaluation, we can become more sophisticated

about defining what constitutes good thinking, and we can gain understanding of the

dispositions and attitudes that good thinkers display. Biggs (1995:15) points out that

assessment occupies a key place in determining quality learning outcomes. Because it has

often been determined by traditional procedures and existing standards, it is beyond an

individual teachers control. He contends for changes in the traditional outdated methods

of assessing students learning outcomes. A universal call for educational reform in

student assessment is noted by others as well (e.g. OTuel & Bullard, 1995:2; Acheson &

Gall, 1992:28).

Research findings have enlightened a new direction of helping the students to

manage their studies, i.e. provide students thinking skills instruction, which may remedy

the shortcomings of the current curriculum and enable students to manage their studies

and later their lives successfully. Over the decades, as revealed by OTuel and Bullard

(1995:233-5), hundreds of thinking skills programs have been designed, however

teachers need to search for desirable programs and effective procedures for

implementation. After search of desirable programs, the author identifies some and

presents Philosophical Inquiry as the most promising approach.

3. Philosophical Inquiry

An instructional design may prescribe an optimal method of instruction and bring

about desired changes in student knowledge and skills (Reigeluth, 1983). OTuel and

Bullard (1995:233-5) note that there are hundreds of higher order thinking (HOT)

programs, which however lack of adequate research on their effectiveness owing to

disagreement on what constitutes higher order thinking and how to measure it. After

searching desirable programs for teaching thinking, the author finds that Philosophical

Inquiry is a promising approach. Using this approach, a teacher attempts to teach thinking

skills through dialogues centred on philosophical issues that emerge from texts or stories.

It requires teachers to build a community of inquiry in the classroom through skilful

questioning, clear logical thinking and ideally training in teaching children philosophy. It

is considered desirable because it can be used by teachers in any subjects within a normal

time-table; no extra time is required as it is not a separate subject; and teachers of the

same year level or department may develop their abilities in teaching thinking skills

either on their own or in a group.

Wilks (1995:vi) states that Matthew Lipman was the first to conceive the idea of

using philosophical issues and approaches with children in the 1960s and wrote a series

of texts from classrooms over two decades. He was influenced by Deweys pedagogy of

coverting classrooms into communities of inquiry and insistence on the importance of

experience in learning. During 1970s and 80s Lipman wrote stories containing

philosophical issues appropriate for discussion in classrooms, such as truth fairness and

equality. Lipman (1985:106-8) believes that creating communities of inquiry for children

may enable them to develop independent and autonomous thinking, therefore he has

created the Philosophy For Children Program in which he wrote stories with

philosophical issues for children of different year levels to explore in the classroom. He

claims that teachers using philosophical inquiry in teaching stories may sharpen 30

thinking skills and produce educationally significant results among students. Lipman

(1993:383) is convinced that philosophy can and should be a part of the entire length of

a childs education.

Splitter and Sharp (1995:8) explain the teaching for better thinking means to

cultivate the forms of behaviour which are linked to better thinking. They state that what

is important is to equip students to make good judgements about the quality of the

thinking which they produce and with which they are confronted (p.12). They state that

the crucial ingredient in the teaching of thinking is the establishment and nurturing of a

classroom environment in which the skills, dispositions and overarching sense of care

constitutive of good thinking, are modelled, cultivated and practised. The classroom

community of inquiry is just such an environment (p.17).

Influenced by Lipman, programs similar to his have been created, e.g. Cams

(1993) Thinking Stories 1 & 2, and Wilks (1995) Creative and Critical Thinking,

providing rich resources for teachers to use philosophical inquiry approach in classroom.

Both Cam and Wilks believe that childrens literature provides a rich source of

philosophical themes which may form an effective stimulus for inquiry in the classroom.

Besides, many different topics over a wide variety of subject areas can also be used.

Philosophical inquiry is a powerful teaching approach in developing students thinking

skills, through establishing a community for inquiry in the classroom. A teacher uses

questioning and group discussion techniques on issues raised from novels or subject

materials. Wilks (1995) has trialed Lipmans program in many schools in Australia, and

has found new and practical approaches as she worked with teachers. She identifies the

thinking skills that can be transferred across the curriculum: reasoning, ability to make

assumptions and inferences, correct and improved thinking, and problem solving.

Philosophical inquiry does not require adding a new subject to the curriculum, or

excluding another, and it can enhance the learning of other subjects. Students learn to

respect others experiences and points of view in the approach. Teachers do not

undermine beliefs or erode values, but help children build foundations and frameworks

for their existing beliefs. There is more student talk, extended student answers, more

interaction between students, less of teacher manipulation, and more thoughtful and open

questions asked by students. In case studies, she found that teachers and students enjoyed

the philosophical inquiry approach, with its challenging and encouraging mode. Many

positive changes in students followed the development of a community of inquiry in the

classroom. Students became eager to participate, prepared to listen to each other and

valued each others comments. De Hann, McCutcheon and MacColl (1995:4) also note

that teaching philosophy at school has immense value because it builds self-esteem and

contributes to the development of independent thinking, good judgement and

reasonableness and stress its benefits for children in their school education. Sharp

(1993:337) states that community of inquiry is an educational means of furthering the

sense of community that is a precondition for actively participating in a democratic

society, and it cultivates skills of dialogue, questioning, reflective inquiry and good

judgment.

3A. Teaching Strategies in Philosophical Inquiry

Teachers may use philosophical inquiry in any subjects, particularly in language and

literature. Wilks (1995) reveals the following teaching strategies for philosophical inquiry:

1. Build up a supportive and nurturing environment in the classrooms that fosters

reasoning, critical and creative thinking. Discuss with students and find the

elements of good discussions, e.g. one person speaking at a time, hands up to

indicate wish to speak, ask for clarification if necessary. Rules may be suggested

by students.

2. Having questions prepared, teachers need to keep the overall aims in mind and take

responsibility for the standard of discussions. Be aware of teaching thinking skills

as aims and desired outcomes.

3. Thinking and dialogue skills are not given by the teachers, but learnt by students

through discussion, giving reasons when statements are made, and correcting

mistakes in students reasoning. Reading and writing are natural outgrowths of

conversation which is the childs natural mode of communication.

4. Be prepared to divide a large class into groups. Try having discussions with a

smaller group; meanwhile set the other group to work on some written work

relevant to the issue.

5. Provide activities involving students in analysis, clarification of values, and

appropriate social action. Questions about ones thinking or thoughts may help

students to become accustomed to discussing abstract concepts.

6. Do not inject the teachers own point of view or judgment into class discussion.

Change the habit of saying after students responses Good, Yes, Well done to

What do you think about what Alex said? Who disagrees? Does anyone have

another example?

7. Do not prompt students for neither answers nor steer a discussion towards the

teachers own view points. Students are asked to elaborate instead of the teacher

doing it for them. Students are encouraged to ask questions to clarify meaning,

which is a vital step towards good communication.

8. Include fast talkers as equal participants, not dominators. One way is to distribute

five matches or buttons to each member who places one into the centre of the

discussion circle after speaking.

9. Reluctant participants may need to be allowed a little longer time, or given cards

with a question written on it.

10. Teachers do not praise too much nor show favour for particular answers, and do

not interrupt student talk nor hinder the flow of conversation.

11. Teachers become the facilitators, rather than the sources of information or

affirmation to student action. Teachers and students become cooperative and

caring co-inquirers.

12. The teacher and students share the solution of a problem as co-inquirers.

Encourage active verbal interactions between students rather than between teacher

and students.

13. During the learning process, which is as important as the subject matter, students

learn to be tolerant, recognize and assess value judgments, and become critical

thinkers.

14. Teachers may evaluate philosophical inquiry sessions with their class using

questions such as: Were the participants listening to one another? Were they

responding directly to one another? Were people encouraged to participate? Was

the topic interesting? Did I challenge my own thinking?

3B. Strategies to Encourage Participation of ESL Students in Discussion

In case studies, Wilks (1995) notes that ESL (English as a Second Language)

teachers found the philosophical inquiry approach very beneficial to their students. Being

engaged in philosophical discussions, students experience a natural way of learning a

language in class through immersion in the spoken language. Students express opinions:

agree or disagree with the opinions of others, clarify meaning, and give examples.

Students learn the sorts of skills and vocabulary that they need to cope with their studies

in schools. ESL teachers may encourage student participation by using the following

strategies:

1. Pre-teach new vocabulary or expressions for ones opinions.

2. Use culturally specific resources. Topics such as truth, goodness, childrens rights,

freedom, duty, may have different meanings among cultures.

3. Teachers need to anticipate cultural and individual differences in discussions.

Cultural differences and similarities, which arise, are rich potential resources for

philosophical discussions.

4. The main idea can be highlighted on the board or repeated to help some students

who have difficulty in understanding the flow of the discussion.

5. Encourage clear expression by asking native speakers to repeat or another student

to express an idea in another way, so that communication is clearer.

6. A teacher may like to recap a discussion to help students consolidate what they

have heard: main ideas discussed, how idea was discussed and new vocabulary

used.

7. Five to ten minutes could be assigned at the end of a session for journal entries.

For example, students may write down a question they find interesting and

mention the various ways it has been considered.

8. Such written work reveals whether students understand the philosophical concepts

and helps students to internalize the vocabulary used.

3C. Establishing Philosophical Inquiry in Schools

To use the philosophical inquiry approach in schools, Wilks (1995) proposes setting

up professional development workshops for teachers who need to discuss and understand

the nature of this approach. In workshop sessions, teachers will learn this approach and

practise how to lead discussions. After a workshop, teachers may explore and choose

texts for inquiry in the classroom. A teacher may prepare a session and run a class with

the trainer, or work in pairs in the early stages of using the philosophical inquiry

approach. Teachers may share their experiences about student participation and the

different kinds of thinking demonstrated during formal or informal meetings. They must

note that sound preparation and evaluation are important in the early sessions, so that

teachers become familiar with the philosophical issues and thinking skills used.

To monitor progress in the classroom, different methods can be used; e.g. checklists

with key elements of a philosophical discussion, a report system listing appropriate skills

and attitudes, or Matthew Lipmans suggested evaluation of student progress. Non-

classroom conversations of children may be recorded to ascertain whether there was a

carry-over of skills from classroom philosophy sessions. Units of work can be designed

with philosophical issues and questions developed for inquiry from everyday literature,

e.g. Famous Fables, and Fairytales.

Teachers need to be familiar with the issues in the stimulus material and any

accompanying exercises. A wide variety of issues can be chosen from materials such as

films, newspaper articles and extracts from movies and literature. Relevant philosophical

questions should be prepared for classroom discussion, probing deeper into issues with

students. A philosophical discussion is characterized by: students thinking being

noticeably challenged, reactive and critical approaches, issues that are often abstract, and

questions having no straight forward answers.

Parents may be informed of the schools educational reasons for introducing

philosophical inquiry in sessions for them. Activities and approaches may be

demonstrated or shown in videotapes to the parents who will understand this approach,

and may get some ideas to develop their childrens minds at home.

A coordinator in a school committed to introducing philosophical inquiry can support

the teachers involved and maintain contact with teacher educators or trainers. Progress

and strategies for future classes can be discussed. Keeping a journal will help in

tracking progress, guiding future practice in discussions and for future planning.

Teachers observing others, sharing ideas and experiences will be enriching themselves.

Spreading ideas from school to school may result in a more effective curriculum change

than a Top-down initiative.

3D. A Teachers Application of Philosophical Inquiry

A teacher who has previous training in philosophy may feel competent to try using

philosophical inquiry as a teaching approach in the classroom. An in-service teacher may

study references, explore resources, and join relevant conferences, seminars or

workshops. Workshops may enable the teacher to be better equipped to implement such

approach through learning the expertise and experiences of educators and other teachers.

Lipman Sharp and Oscanyan (1984) provide a series of dos and dont to go together with

their instructional manuals in using philosophical inquiry, and give practical suggestions

for carrying out discussions effectively (pp. i-ii). Teachers are free to develop their own

style after they become familiar with their manuals. Wilks (1995:34-54) has provided

case studies which reveal valuable experiences and ideas of choosing resources, session

planning, developing issues, good questioning and implementation of this approach in

schools. She notes that teachers usually used materials which were specially designed for

introducing philosophical issues at first, but later they included other resources as they

accumulated confidence. Examples of designed units of work are also provided to

demonstrate the philosophical issues present in literature. A unit may consist of a story,

objectives of the session, a discussion planned with philosophical questions, and activity.

For upper classes, a unit may consist of a longer story, more objectives, questions and

appropriate activities.

4. Problems Associated With The Teaching Of Thinking

4A. Lack of Teacher Training

Without training, teachers lack the skills to teach students thinking. Teachers have

been students previously and they are likely to teach in the way that they were taught -

traditional didactic style. Some teachers probably have their own firm beliefs and

consider themselves authoritative with long experiences. They may insist on upholding

tradition and refuse to change. Therefore, it is proposed that teacher education should

include how to give thinking skills instruction to students. When more and more teachers

know how to teach thinking, they may be able to initiate and support curriculum change.

Presently school administrators and staff may join workshops, conferences, or seminars

to learn new ideas, be acquainted with new research findings and learn new methods to

teach students thinking. The principals may encourage department heads and senior

teachers to be trained to supervise other teachers in giving effective thinking skills

instruction. Teachers need to be supported to develop their thinking skills through

providing them professional development opportunities and resources, and chances to

reflect and share ideas in formal or informal meetings. Teachers may develop their

repertoire in teaching thinking through supervision by competent instruction leaders, peer

class observation and regular reflection.

4B. Assessment of Learning Outcomes

Another major problem is the lack of well designed tools in assessing thinking skills

as learning outcomes. Traditionally the assessment of student learning outcomes has been

focused on the content learnt, and students have been required to retrieve facts or

information memorized in standardized tests. However, this kind of assessment does not

reflect students thinking skills which are important skills needed not only in their studies,

but as citizens in future. Biggs (1995) points out that assessment occupies a key place in

determining quality learning outcomes. The traditional assessment practices of students

learning outcomes are outdated and they need to be changed. However, the change will

be beyond an individual teachers control because the assessment practices have often

been determined by traditional procedures and existing standards. The change will also

be complicated and it will affect all levels in the existing system of the institution. In

future the assessment of the acquisition and application of thinking skills will hopefully

be well constructed, if the teaching of thinking is to be regarded as an integral and

focused part of the school curriculum teaching. Meanwhile teachers may design their

own assessment tools or make use of the tools available (e.g. Costa, 1991).

4C. Problems with Philosophical Inquiry

Wilks (1992) reveals some problems related to using philosophical inquiry as a

teaching approach in schools. Some teachers did not value activities and discussions,

which do not appear to have a specific end, and this attitude affects their students. They

often believe that they have most of the answers, and they are used to giving answers to

students questions. Teachers may fear that philosophical discussions will lead to no

definite answers, causing their authoritative image to be undermined. This fear can be

overcome by teachers knowing the nature of philosophical discussions, which normally

have no right answers. Workshops and help by trainers in philosophical inquiry may

equip teachers with skills for leading such discussions. Marks or results are seen to be

important, particularly for the final years of secondary schooling. Traditionally,

established assessment tools for the final year of secondary schooling cannot be

changed easily without very strong evidence of faults. At present, one cannot remove

the emphasis on test scores. If the philosophical inquiry approach can be used in the

earlier years, students may acquire the desired thinking skills to manage their studies. If

teachers can experiment with the powerful approach in higher forms, they may be able

to see for themselves how students can be helped by this approach.

Students who have been successful in the traditional teaching mode may be annoyed

to see the less involved students becoming involved. These students can feel threatened

because they have been trained in the traditional mode which values only what can be

examined and tested. To solve this problem, teachers need to find ways of encouraging

all students to contribute, and to respect others opinions and styles. Skilful teachers may

use strategies to encourage active participation by all students, e.g. treat the fast talkers

equally with the others, allow a greater waiting period for a slower participant and value

the input of each group member. Mix good contributors and non-contributors together, or

group students who do not normally contribute, or group the fast thinkers (Wilks,

1992:48-75).

5. Suggestions For Implementation

On the verge of the new millennium, school leaders are pressured, from outside and

within schools, to cope with numerous changes relating to different issues. One possible

change may be towards a thinking curriculum advocated by many educators. In this

section, suggestions are given for implementation of the teaching of thinking in general

which applies to using the Philosophical Inquiry approach as well.

5A. School Administration and Leadership

Nisbet (1993) states that the changing social and economic demands of the

modern societies have obliged the school leaders to change the traditional educational

systems. The curricula are to be restructured and methods redesigned to promote and

practise thinking and reasoning within the traditional curriculum subjects. School leaders

must now aim at broader competencies than the traditional basic skills. Sternberg

(1987:255) points out the need of a comprehensive formal evaluation to show the worth

of a thinking skills program, and it may include standardised thinking skills and

intelligence tests, measures of achievement, measures of attitudes towards thinking and

learning, or measures of study habits. He believes that thinking skills instruction should

continue throughout schooling as it is for subjects like mathematics or social studies.

Psychological research reveals that the transfer of training cannot occur easily but

students need to be taught for transfer. In order to maximize transfer in a thinking skills

training program, students must learn to think flexibly, look for opportunities to transfer

their skills, and seek analogies between past and future situations. Principles and rules of

thinking must be presented in varied academic subjects. Students can be helped to see the

relevance of these principles across subjects through varied examples chosen from

different subjects, and be expected to apply these skills if they are given examples of

transfer in everyday situations. Instruction is ideally given through multiple media. Then

students may internalize what they are taught and transfer it to real life situations.

For any program to be successful, it is important to win the support of administrators

and teachers who should have a vision for what the school and its students can become.

Researchers find that effective principals target career development for some or all staff,

largely based on frequent in-class observations. Teachers are encouraged to visit each

others classes and learn from each other. A systematic development of an instructional

leadership team may carry out the functions of curriculum, instructional coordination and

supervision. This system includes the rationale, a framework, a process, a method for

assessment, and an approach to develop skills of team members. The principal is the

initiator and leader of the team and remains responsible for its performance (e.g.

Hallinger, 1989:319-29).

Paul (1994) suggests that administrators need to support teachers in the process of

teaching students critical thinking, through on-going structures and activities such as:

making and sharing video tapes, sending key personnel to conferences, establishing

working committees, informal discussion groups, and opportunities for peer review. They

need to show appreciation of teachers effort, provide time and handbooks for

professional development; and actively participate in in-service development. An

educational approach to morality is to be adopted, rather than a doctrinaire one.

Administrators and school leaders should be ready, willing, and be able to explain why

and how critical thinking and ethics are integrated throughout the curriculum. The School

Board, the community or the district should have the enthusiasm to preserve or even fight

for the ideal. Close-minded people may see morality personified in their particular moral

perspectives and beliefs, and hold on to the traditional way of teaching. Make a critical

and moral commitment to a moral and critical education for all students and do this in a

way that demonstrates to teachers and parents alike moral courage, moral perseverance,

and moral integrity (Paul, 1994:374).

5B. Curriculum Change and Action Research

Hill (1995), after wide studies in school effectiveness, reveals that school

improvement is a process and there are no simple blue-prints or recipes. The power of

information about school effectiveness acts as a catalyst for improvement and reform,

and it is increasingly recognized as a means of motivating and shaping improvement

efforts. A similar view is held by Deal (1988:202), Hopkins (1994:1-14) and Grundy

(1995:5) who state that research findings are powerful and may pave the way to reshape

the character of schools, map the process of change and improve schools. Lewis

(1985:139) reveals that in using action research, one schools attempt was highly

successful in strengthening the schools capacity in problem solving and training the staff.

There was a measurable reduction of frustration and confusion amongst colleagues,

improved communication among all parts of the school community and an increase in

innovation within the classrooms. Whether using an in-content or out-of-content program

for teaching thinking, action research may be employed to guide the process of

implementation. The research group aims at improving practical judgment in concrete

situations during the whole process. Its main usefulness is in helping the people involved

to function more intelligently and skilfully (Kemmis, 1988; Burns, 1994; and Grundy,

1995:9).

The research participants can be the Principal, the Deputy Principal, an assistant

master/mistress and any elected or voluntary teachers. A member of a school board, a

school counsellor or a district educational department official may also be involved with

the research process. The research will be designed, implemented, evaluated and finally

reported to the staff, the school board or anybody concerned. For the research group,

many questions can be asked: How resources can teachers use to help each other and the

students to be excellent thinkers? What professional development programs or workshops

are to be designed to equip teachers with skills to teach thinking? How do teachers design

instruction for different subjects and for different year levels? Any problem situations

will be diagnosed, then remedial action will be planned and implemented, and its effects

monitored. Action research procedures for the implemention of a thinking skills program

are outlined in the following. Ideas may be drawn from Burn (1994) and Kemmis (1988).

6. Conclusions And Recommendations

School leaders are challenged to lead with strong commitment, particularly in the

present turbulent educational environment, and bring successful experiences to students

in future. Many researchers and educators have worked hard to find what the most

important knowledge is for the learners, and the new ways to teach that knowledge. That

results in their advocacy for teaching students thinking skills which are assumed to

transform students to be strong thinkers, enable them to manage their studies and later

their lives in the society. The author has outlined one in-content thinking skills programs

- Philosophical Inquiry - which requires teachers to possess clear logical thinking, build a

community of inquiry in the classroom through skilful questioning, and preferably have

training in teaching children philosophy. However, teachers may feel competent and

knowledgeable enough to try out this program. The progress of implementing the

program will best be monitored by the instructional leadership team or the action research

group whose research findings will enable the teachers to see the effectiveness of the

program. Their applications will not require extra time to be scheduled in the school

time-table, nor extra textbooks for students. However, they require school administrators

and leaders to support the teachers by providing them resources, professional

development opportunities or in-service training to develop their thinking skills and

teaching strategies.

Before teachers start any thinking skills program, they may start at once individually

using techniques to develop students thinking through using simple strategies such as

thinking aloud, brainstorming, students sharing ideas and learning strategies. Teachers

may find useful references and resources for thinking skills instruction available in book

stores. They will be much supported if publishers produce materials for giving thinking

skills instruction in schools. For example, Hawker Brownlow Education in Australia, is a

well-known publisher in producing excellent resources for the teaching of thinking.

Approaching the new millennium, the school curriculum for a democratic society should

encourage individuals to develop their mind fully.

References

Acheson, K. A. & Gall, M. D. (1992). Techniques in the clinical supervision of teachers. 3rd. ed. New

York & London: Longman.

Baron, J . B. & Sternberg, R. J. (Eds). (1987). Teaching thinking skills: theory and practice. New York:

W.H. Freeman.

Beyer, B. K. (1991). What philosophy offers to the teaching of thinking. In Costa, A, (Ed.). Thinking, Vol.2.

Rev. ed. Virginia: Association for Supervision and Teaching.

Biggs, J . B. & Telfer, R. (1987). The process of learning. 2nd ed. Prentice-Hall of Australia.

Biggs, J . (1995). Assessing for learning, some dimensions underlying new approaches to educational

assessment. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research, Vol. XLI, (1), 1-17.

Bowden, J . A. (Ed.). (1986). Student learning: research into practice. The University of Melbourne.

Burns, R. B. (1994). Introduction to research methods. 2nd ed. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire.

Cam, P. (1993). Thinking Stories 1 & 2. Sydney: Hale & Ironmonger.

Costa, A. L. (Ed.). (1991). Developing minds: a resource book for teaching thinking. Rev. ed. Vol. 1.

Alexandria, Virginia: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

De Bono, E. (1991). The direct teaching of thinking in education and the CoRT method. In, Maclure, S.

(Ed.), Learning to think: thinking to learn. Pergamon Press.

De Hann, C. , McCutcheon, L. & MacColl, S. (1995). Philosophy with kids, Book 1. Melbourne: Longman.

Deal, T. E. (1988). The symbolism of effective schools. In Westoby, A. (Ed.), Culture and power in

educational organizations. Milton Keynes, Philadelphia: The Open University Press.

Gredler, M. E. (1992). Learning and instruction: theory into practice. 2nd ed. Macmillan Publishing Co.

Grundy, S. (1995). Action research as professional development. Innovative Links project.

Hallinger, P. (1989). Developing instructional leadership teams in high schools. In, Reynolds, D., Creemers,

D. & Peters, T. (Eds.), School effectiveness and school improvement. Amsterdam: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Hill, P. (1995). School effectiveness and improvement. Deans lecture series. The University of Melbourne.

Hopkins, D. (1994). Towards effective school improvement. Keynote address to the international congress

for school effectiveness and school improvement. Leeuwarden Netherlands. 6 J an. 1995.

Husen, T. & Postlethwaite, T. N. (1992). International encyclopaedia of education. 2nd ed. Oxford:

Pergamon Press.

Kauchak, D. & Eggen, P. D. (1989). Learning and teaching: research based methods. Boston: Allyn &

Bacon.

Kemmis, S. (1988). Action research. In, Keeves, J . (Ed.), Educational research methodology, and

measurement.

Lewis, J . (1985). The theoretical underpinnings of school change strategies. In, Reynolds, D. (Ed.).

Studying school effectiveness (pp. 137-154). London: The Falmer Press.

Lipman, M. (Ed.). (1993) Thinking children and education. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing.

Lipman, M., Sharp, A. M. & Oscanyan, F. S. (Eds.). (1984). Philosphical inquiry: an instructional manual

to accompany Harry Stottlemeiers discovery. 2

nd

ed. Lanham, MD: University of America.

Lipman, M. (1985). Thinking skills fostered by philosophy for children. In, Segal, J . W., Chipman, S. F. &

Glaser, R. (Eds.). Thinking and learning skills: Volume 1: relating instruction to research. London;

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mulcahy, R. et al. (1993). Cognitive education project (summary project). Alberta Department of

Education. ED367682.

Nisbet, J . (1993). The thinking curriculum. Educational psychology, 13(3), 280-290.

OTuel, F. S. & Bullard, R. K. (1995). Developing higher order thinking in the content areas: K-12.

Victoria: Hawker Brownlow Education.

Paul, R. (1994). Critical thinking: what every person needs to survive in a rapidly changing world. Victoria,

Hawker Brownlow Education.

Paul, R., Binker, A.J.A. & Weil, D. (1993). Critical thinking handbook: a guide for remodelling lesson

plans in language arts, social studies & science, up to year 3. Victoria: Hawker Brownlow Education.

Paul, R. et al. (1993). Critical thinking handbook: a guide for redesigning instruction, year 11-12. Victoria:

Hawker Brownlow Education.Prawat.

Reigeluth, C. M. (Ed.). (1983). Instructional-design theories and models: an overview of their current

status. New J ersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ruggiero, V. R. (1995). The art of thinking: a guide to critical and creative thought. 4th ed. New York:

Harper Collins College Publishers.

Sharp, A. M. (1993). The community of inquiry: education for democracy. In, Lipman, M. (Ed.), Thinking

children and education, pp. 337- 345. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing.

Splitter, L. J . & Sharp, A. M. (1995). Teaching for better thinking: the classroom community of inquiry.

Melbourne: The Australian Council for Educational Research Ltd.

Sternberg, R. J . (1987). In, Boykoff, B. J . & Sternberg, R. J . Teaching thinking skills: theory and practice.

New York: W.H. Freeman.

Wilks, S. (1992). An evaluation of Lipmans Philosophy for Children Program. Master of Education Thesis,

University of Melbourne.

Wilks, S. (1995). Critical & creative thinking. Australia, Armadale: Eleanor Curtain.

____________________

Author

Connie Chuen Ying YU, EdD candidate, Department of Education Policy and Management,

Faculty of Education, University of Melbourne

(Received 31.5.99, accepted 5.7.99, revised 15.8.99)

You might also like

- Process-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning: Pogil and The Pogil ProjectDocument12 pagesProcess-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning: Pogil and The Pogil ProjectainuzzahrsNo ratings yet

- IJRPR2036Document4 pagesIJRPR2036xtinelorraine111499No ratings yet

- Worksheet in Foundation of Special and Inclusive EducationDocument3 pagesWorksheet in Foundation of Special and Inclusive EducationANGELO ORIBIANo ratings yet

- Report - Curriculum Design and OrganizationDocument43 pagesReport - Curriculum Design and OrganizationJanet Bela - Lapiz100% (6)

- Concept Based Learning - Final Essay-1Document45 pagesConcept Based Learning - Final Essay-1RP17 CE21No ratings yet

- ConstructivismDocument6 pagesConstructivismZarah HonradeNo ratings yet

- Article On Critical Thinking SkillDocument23 pagesArticle On Critical Thinking SkilltisuchiNo ratings yet

- ICT in Constructivist Teaching of Thinking Skills PDFDocument24 pagesICT in Constructivist Teaching of Thinking Skills PDFFiorE' BellE'No ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning ProcessDocument5 pagesTeaching and Learning ProcessQurban NazariNo ratings yet

- Teaching PlanDocument6 pagesTeaching PlanMAE ERNACIONo ratings yet

- From Thinking Skills To Thinking Classrooms: Key ConclusionsDocument7 pagesFrom Thinking Skills To Thinking Classrooms: Key ConclusionsGhazally FaridahNo ratings yet

- Upgrading Critical Thinking SkillsDocument9 pagesUpgrading Critical Thinking SkillsEgoku SarkodesNo ratings yet

- Developing Critical Thinking Through Cooperative LearningDocument9 pagesDeveloping Critical Thinking Through Cooperative LearningriddockNo ratings yet

- Constructivism Paradigm of TheoriesDocument32 pagesConstructivism Paradigm of Theoriesman_dainese100% (1)

- From Thinking Skills To Thinking Classrooms Carol MguinnesDocument6 pagesFrom Thinking Skills To Thinking Classrooms Carol MguinnesMaria Del Carmen PinedaNo ratings yet

- Mascolo Beyond Teacher Centered and Student Centered LearningDocument25 pagesMascolo Beyond Teacher Centered and Student Centered LearningVioleta HanganNo ratings yet

- Constructivist Teaching MethodsDocument7 pagesConstructivist Teaching Methodsamit12raj100% (1)

- Pedagogical Innovations in School Educat PDFDocument18 pagesPedagogical Innovations in School Educat PDFTaniyaNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Considerations Guide Curriculum Theories and ApproachesDocument4 pagesPhilosophical Considerations Guide Curriculum Theories and ApproachesWhy D. Hell-NotNo ratings yet

- How Student Learn 4Document8 pagesHow Student Learn 4Ainun BadriahNo ratings yet

- Objectives: Republic Act No. 10533Document5 pagesObjectives: Republic Act No. 10533JERIC A. REBULLOSNo ratings yet

- 378 - Ok EDUC 30073 - Facilitating Learner Centered-Teaching - Manolito San Jose (Edited)Document56 pages378 - Ok EDUC 30073 - Facilitating Learner Centered-Teaching - Manolito San Jose (Edited)Denise CopeNo ratings yet

- 7 Principles Constructivist EducationDocument2 pages7 Principles Constructivist EducationSalNua Salsabila100% (13)

- Metacognition.: Activity 1: Explain The Meaning of MetacognitionDocument26 pagesMetacognition.: Activity 1: Explain The Meaning of MetacognitionMarjon LapitanNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Activity 7Document1 pageCurriculum Activity 7Ronnel ManilingNo ratings yet

- Behaviorist Theories: Learning Theories Are An Organized Set of Principles Explaining How Individuals AcquireDocument14 pagesBehaviorist Theories: Learning Theories Are An Organized Set of Principles Explaining How Individuals AcquirePrakruthiSatish100% (2)

- Theories in Learning ScienceDocument4 pagesTheories in Learning ScienceRogie P. BacosaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper GriswoldDocument27 pagesResearch Paper Griswoldapi-291877516No ratings yet

- Activity Based Approach For JBT StudentsDocument11 pagesActivity Based Approach For JBT StudentsVIJAY KUMAR HEERNo ratings yet

- Constructivist Teaching Methods - WikipediaDocument54 pagesConstructivist Teaching Methods - Wikipediatajum pullomNo ratings yet

- Delm112-Social, Psychological, and Philosophical Issues in EducationDocument10 pagesDelm112-Social, Psychological, and Philosophical Issues in EducationSonny Matias100% (3)

- Report - Unit 1 Topic 2Document6 pagesReport - Unit 1 Topic 2LanieNo ratings yet

- Ajmcsr11 161Document5 pagesAjmcsr11 161MarkusNo ratings yet

- Classroom Debate To Enhance Critical Thinking SkillsDocument17 pagesClassroom Debate To Enhance Critical Thinking SkillsShajjia ZainabNo ratings yet

- Embedding Learning Technologies: Productive Pedagogies ModelDocument30 pagesEmbedding Learning Technologies: Productive Pedagogies Modelevon1100% (3)

- 5804-Article Text-11317-1-10-20210121Document15 pages5804-Article Text-11317-1-10-20210121Karolina DudekNo ratings yet

- ISC3701 Assessment 2 - Learning Theories, Instructional Models, African-Based TeachingDocument11 pagesISC3701 Assessment 2 - Learning Theories, Instructional Models, African-Based TeachingAngelo du ToitNo ratings yet

- 5e Lesson CycleDocument11 pages5e Lesson Cycleapi-275511416No ratings yet

- Various Philosophies of Education Nilda O. Babaran - PHDDocument13 pagesVarious Philosophies of Education Nilda O. Babaran - PHDCONSTANTINO, JELAY P.No ratings yet

- Pedagogies in Teaching EsPDocument42 pagesPedagogies in Teaching EsPluzviminda loreno100% (1)

- Project Based ApproachDocument27 pagesProject Based ApproachLaura100% (3)

- Pme 810 Connecting With My Professional CommunityDocument21 pagesPme 810 Connecting With My Professional Communityapi-334266202No ratings yet

- Philosophical Foundations: A. PerennialismDocument7 pagesPhilosophical Foundations: A. PerennialismXerxex CelistinoNo ratings yet

- 1bruners Spiral Curriculum For Teaching & LearningDocument7 pages1bruners Spiral Curriculum For Teaching & LearningNohaNo ratings yet

- Constructivism and Socio-Constructivism TEACHING 1: Fall 2022 3 WeekDocument25 pagesConstructivism and Socio-Constructivism TEACHING 1: Fall 2022 3 WeekhibaNo ratings yet

- Facilitating Leaner Centered TeachingDocument27 pagesFacilitating Leaner Centered TeachingBann Ayot100% (1)

- IMD - Wk1 - Theories and Foundations of Instructional DesignDocument8 pagesIMD - Wk1 - Theories and Foundations of Instructional DesignRICHARD ALFEO ORIGINALNo ratings yet

- Binet and Assessments of Intelligence. About The Time That Thorndike Was Developing Measures ofDocument4 pagesBinet and Assessments of Intelligence. About The Time That Thorndike Was Developing Measures ofSofíaNo ratings yet

- Encouraging Higher Level ThinkingDocument9 pagesEncouraging Higher Level ThinkingArwina Syazwani Binti GhazaliNo ratings yet

- Getting The Students To LearnDocument2 pagesGetting The Students To Learns_ghufronNo ratings yet

- Learning Theories (On How People Learn) Dr. Azidah Abu ZidenDocument36 pagesLearning Theories (On How People Learn) Dr. Azidah Abu ZidenFarrah HussinNo ratings yet

- Supplementary Workbook - 3S, Inquiry in The PYP - Babin & RhoadsDocument57 pagesSupplementary Workbook - 3S, Inquiry in The PYP - Babin & RhoadsAnsari Nuzhat100% (1)

- Habits of Mind in The CurriculumDocument10 pagesHabits of Mind in The CurriculumPrakash NargattiNo ratings yet

- Motivating Project Based Learning Sustaining The Doing Supporting The LearningDocument31 pagesMotivating Project Based Learning Sustaining The Doing Supporting The LearningCristina100% (1)

- Philosophy Refllection 4Document3 pagesPhilosophy Refllection 4kimbeerlyn doromasNo ratings yet

- How to Teach Kids Anything: Create Hungry Learners Who Can Remember, Synthesize, and Apply KnowledgeFrom EverandHow to Teach Kids Anything: Create Hungry Learners Who Can Remember, Synthesize, and Apply KnowledgeNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of Teachers’ Questions and Tasks to Develop Reading Comprehension: The Application of the Cogaff Taxonomy in Developing Critical Thinking Skills in MalaysiaFrom EverandAn Investigation of Teachers’ Questions and Tasks to Develop Reading Comprehension: The Application of the Cogaff Taxonomy in Developing Critical Thinking Skills in MalaysiaNo ratings yet

- A Team-Based Learning Guide for Students in Health Professional SchoolsFrom EverandA Team-Based Learning Guide for Students in Health Professional SchoolsNo ratings yet

- Summary of Ron Ritchhart, Mark Church & Karin Morrison's Making Thinking VisibleFrom EverandSummary of Ron Ritchhart, Mark Church & Karin Morrison's Making Thinking VisibleNo ratings yet

- Bhavartha Ratnakara: ReferencesDocument2 pagesBhavartha Ratnakara: ReferencescrppypolNo ratings yet

- Sample File: Official Game AccessoryDocument6 pagesSample File: Official Game AccessoryJose L GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Duah'sDocument3 pagesDuah'sZareefNo ratings yet

- One Shot To The HeadDocument157 pagesOne Shot To The HeadEdison ChingNo ratings yet

- Reviews: Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery: A Shift in Eligibility and Success CriteriaDocument13 pagesReviews: Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery: A Shift in Eligibility and Success CriteriaJulia SCNo ratings yet

- Metabical Positioning and CommunicationDocument15 pagesMetabical Positioning and CommunicationJSheikh100% (2)

- The Way To Sell: Powered byDocument25 pagesThe Way To Sell: Powered bysagarsononiNo ratings yet

- Development of Branchial ArchesDocument4 pagesDevelopment of Branchial ArchesFidz LiankoNo ratings yet

- Signal WordsDocument2 pagesSignal WordsJaol1976No ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantages of A MonopolyDocument7 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of A MonopolyRosalyn RayosNo ratings yet

- As 3778.6.3-1992 Measurement of Water Flow in Open Channels Measuring Devices Instruments and Equipment - CalDocument7 pagesAs 3778.6.3-1992 Measurement of Water Flow in Open Channels Measuring Devices Instruments and Equipment - CalSAI Global - APACNo ratings yet

- Masala Kitchen Menus: Chowpatty ChatDocument6 pagesMasala Kitchen Menus: Chowpatty ChatAlex ShparberNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice Test - 66253Document2 pagesMultiple Choice Test - 66253mvjNo ratings yet

- Proposal For Funding of Computer Programme (NASS)Document6 pagesProposal For Funding of Computer Programme (NASS)Foster Boateng67% (3)

- Analyzing Evidence of College Readiness: A Tri-Level Empirical & Conceptual FrameworkDocument66 pagesAnalyzing Evidence of College Readiness: A Tri-Level Empirical & Conceptual FrameworkJinky RegonayNo ratings yet

- Group 1 RDL2Document101 pagesGroup 1 RDL2ChristelNo ratings yet

- Basic Statistical Tools for Data Analysis and Quality EvaluationDocument45 pagesBasic Statistical Tools for Data Analysis and Quality EvaluationfarjanaNo ratings yet

- Configure Windows 10 for Aloha POSDocument7 pagesConfigure Windows 10 for Aloha POSBobbyMocorroNo ratings yet

- People v. De Joya dying declaration incompleteDocument1 pagePeople v. De Joya dying declaration incompletelividNo ratings yet

- Edu 510 Final ProjectDocument13 pagesEdu 510 Final Projectapi-324235159No ratings yet

- Q-Win S Se QuickguideDocument22 pagesQ-Win S Se QuickguideAndres DennisNo ratings yet

- Digoxin FABDocument6 pagesDigoxin FABqwer22No ratings yet

- 1st PU Chemistry Test Sep 2014 PDFDocument1 page1st PU Chemistry Test Sep 2014 PDFPrasad C M86% (7)

- Planning Levels and Types for Organizational SuccessDocument20 pagesPlanning Levels and Types for Organizational SuccessLala Ckee100% (1)

- Class 11 English Snapshots Chapter 1Document2 pagesClass 11 English Snapshots Chapter 1Harsh彡Eagle彡No ratings yet

- Ductile Brittle TransitionDocument7 pagesDuctile Brittle TransitionAndrea CalderaNo ratings yet

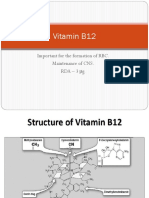

- Vitamin B12: Essential for RBC Formation and CNS MaintenanceDocument19 pagesVitamin B12: Essential for RBC Formation and CNS MaintenanceHari PrasathNo ratings yet

- 317 Midterm QuizDocument5 pages317 Midterm QuizNikoruNo ratings yet

- Second Periodic Test - 2018-2019Document21 pagesSecond Periodic Test - 2018-2019JUVELYN BELLITANo ratings yet

- Ice Task 2Document2 pagesIce Task 2nenelindelwa274No ratings yet