Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wilcock-Reflections On Doing, Being and Becoming - PR

Uploaded by

Isabel Pereira0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

495 views11 pagesA medical view of disorder has had a very constraining influence on the growth of our profession. A simple way to talk about occupation that appeals to a wide range of people is as a synthesis of doing, being and becoming. Occupational therapists need to be able to identify and address occupational dysfunction and occupational wellness.

Original Description:

Original Title

Wilcock-reflections on Doing, Being and Becoming -Pr

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentA medical view of disorder has had a very constraining influence on the growth of our profession. A simple way to talk about occupation that appeals to a wide range of people is as a synthesis of doing, being and becoming. Occupational therapists need to be able to identify and address occupational dysfunction and occupational wellness.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

495 views11 pagesWilcock-Reflections On Doing, Being and Becoming - PR

Uploaded by

Isabel PereiraA medical view of disorder has had a very constraining influence on the growth of our profession. A simple way to talk about occupation that appeals to a wide range of people is as a synthesis of doing, being and becoming. Occupational therapists need to be able to identify and address occupational dysfunction and occupational wellness.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 11

I NTRODUCTI ON

I describe myself as an occupational scientist as well as an

occupational therapist. Over the past decade I have devel-

oped a view of the occupational nature of humans as a

result of a historical inquiry into the relationship between

occupation and health. During the same time, I immersed

myself in notions of health from a public health perspec-

tive. The insights I gained of a very broad concept of

health and occupational needs has led to a perspective of

occupational dysfunction and occupational wellness that is

not constrained by a medical view of disorder.

A medical view of disorder has had a very constraining

influence on the growth of our profession. Like most other

health professions, and the public at large, we talk, write

and think about handicap, illness and dysfunction, as well

as health and wellness, using the concepts and words of

medical science. As a result of my research, I believe we

should no longer do this because a medical science view

masks the very strong relationship that exists between

Australian Occupational Therapy Journal (1999) 46, 111

F e a t u r e A r t i c l e O A 1 7 4 E N

Refl ecti ons on doi ng, bei ng and becomi ng*

Ann Al l art Wi l cock

School of Occupational Therapy, University of South Australia, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

Occupation, and its relationship with health and well-being, is very complex. It can be described in many

different ways by the profession within which it is so central that it provides its name. A simple way to talk about

occupation that appears to appeal to a wide range of people is as a synthesis of doing, being and becoming. In the

present paper I reflect on how a dynamic balance between doing and being is central to healthy living and

wellness, and how becoming whatever a person, or a community, is best fitted to become is dependent on both.

Doing is often used as a synonym for occupation within our profession and is so important that it is impossible to

envisage the world of humans without it. Being encapsulates such notions as nature and essence, about being true

to ourselves, to our individual capacities and in all that we do. Becoming adds to the idea of being a sense of

future and holds the notions of transformation and self actualization. It is a concept that sits well with enabling

occupation and with ideas about human development, growth and potential. Occupational therapists are in the

business of helping people to transform their lives through enabling them to do and to be and through the process

of becoming. In combination doing, being and becoming are integral to occupational therapy philosophy, process

and outcomes, and some attention is given as to how we may best utilize these in self growth, professional

practice, student teaching and learning, or towards social and global change for healthier lifestyles.

KEY WORDS balance, becoming, being, doing, occupation, potential.

A. Allart Wilcock DipCOT, BAppScOT, GradDipPublicHealth, PhD; Associate Professor of Occupational Therapy, School of Occupational Therapy,

University of South Australia, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia.

Correspondence: Box 128, Normanville, SA 5204, Australia.

*This paper is republished with kind permission from the Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. The paper was first published as: Allart

Wilcock, A. (1998). Doing, being, becoming. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65, 248257.

Accepted for publication October 1998.

occupation and health; that occupation is the natural bio-

logical mechanism for health. In this vein, I welcome the

opportunity to encourage you to break down the barriers

that have constrained our understanding of the potential

and importance of occupational therapy.

Occupational dysfunction can result from bodily dis-

order or mental disease, but as long as we are constrained

by these categories we fail to see and work towards allevi-

ating occupational dysfunction from social, political and

ecological causes that are reaching epidemic proportions

all over the world. These causes impact on our traditional

client group, but we feel powerless to act in the larger

struggle because we have not thought about ourselves as

the profession with expertise about the occupational

nature of people, but rather about serving the needs of a

small group of people with occupational dysfunction of a

medically determined nature. If we start to think and act

from the perspective of peoples occupational nature, we

will meet the needs of our traditional client group better

and begin to address the occupational health of popula-

tions at large. In order to do this, we have to appreciate

that our profession embraces a unique understanding of

occupation that includes all the things that people do, the

relationship of what they do with who they are as humans

and that through occupation they are in a constant state of

becoming different.

In the present paper I discuss doing, being and becom-

ing and reflect on how a dynamic balance between doing

and being is central to healthy living and how becoming

whatever a person is best fitted to become is dependent on

both. Becoming is a concept that sits well with enabling

occupation, which has been so well described in the recent

book of the same name, researched and written for the

Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists

(CAOT) and edited by Townsend (Canadian Association

of Occupational Therapists, 1997). In combination, doing,

being and becoming are integral to occupational therapy

philosophy, process and outcomes because, together, they

epitomise occupation.

In reflecting on what may appear to be very

metaphilosophical concepts, I intend to do so in a way that

attempts to satisfy the practical souls of most occupational

therapists by addressing them in the simple, straight-

forward way that I have come to understand them. But

first, I need to acknowledge a few of the many others who

have gone before, particularly with regard to the notion of

being. Philosophers, such as Aristotle, have pondered over

the notion at least since the earliest written records of

thought. Being is a fundamental notion in ontology,

metaphysics, idealism and existentialism (Norton, 1995).

Heidegger, an existentialist, is worthy of special note

because his ideas about being (Krell, 1993) are incor-

porated within ontological research approaches that are

beginning to appeal more and more to occupational

therapy researchers. Another of note, the psychologist

Maslow, wrote his view in Towards a Psychology of Being

(1968) and within this and subsequent texts introduced the

notion of self actualization and transcendence, which are a

part of the notion of becoming. Fidler recognized the rela-

tionship between self actualization and doing in a paper

entitled Doing and becoming: Purposeful action and self

actualisation (1978) and the geographer Rowles (1990)

presents a view that occupational therapists should con-

sider being as a central concept of the profession. My own

views have been greatly influenced by Whiteford in our

discussions over her research about being and becoming

culturally competent occupational therapists (G. White-

ford, pers. comm., 199598) and by a book called Medita-

tions for Women Who Do Too Much (Wilson Schaef,

1990), both of which provide some key thoughts in the

present paper.

As a result of my research, I believe that a very strong

relationship exists between occupation and health, to the

extent that occupation is the natural biological mechanism

for health. To provide a light-hearted look at my public

health view of the potential place of occupation in health

care, I will share with you a fairy story I devised for the

Hong Kong International Congress in 1997. I call it a piece

of occupational science fiction.

Once upon a time there was a group of friends, Creatus,

Dextrus, Mathus, Runna, Scolla and Singa. They all lived

in a small village and were very happy because the vil-

lagers knew them as individuals and made them feel that

each had something special to contribute to community

life.

One day they decided it was time to explore the world

and develop their special talents further. They set off with

high hopes for the Kingdom of Oz, which, they saw from

the news on their television sets, was very rich and very

go ahead. The ruler of Oz, King Oczomby, believed in

equality for the people. He decreed that, according to

age, virtually everyone should do the same things for the

same length of time for the same rewards according to

the economic growth of the country. In order to help him

A. A. Wilcock

2

achieve these goals he had three supervisors,

Ocalianashan, Ocdeprevashan and Ocimbalans. They

made sure that everyone obeyed and valued the rules.

There was one major problem in the Kingdom of Oz.

People were always getting sick. The hospitals had long

waiting lists and there were many fat file patients who

kept coming back. The doctors couldnt offer an explana-

tion. Creatus, Dextrus, Mathus, Runna, Scolla and Singa

all got sick too. Creatus became hypertensive, Dextrus

experienced stress-related allergies, Mathus suffered

from anxiety attacks, Runna had a problem with obesity,

Scolla became bored and depressed and Singa started to

smoke and drink too much.

It was during the time that they were in hospital that

King Oczomby decided he had to tackle this problem in a

new way. He had heard that a new science was emerging

called occupational science and that this was closely asso-

ciated with occupational therapy. He knew very little

about occupational therapists or scientists but decided to

invite one of each of Oscie and Ottie to consult and

advise at the hospital.

Oscie and Ottie talked to Creatus, Dextrus, Mathus,

Runna, Scolla and Singa. They listened to the tales of

their happy life in the village and of their dreams. They

also talked to the King and to Ocalianashan, Ocdepre-

vashan and Ocimbalans about the values, rules and struc-

tures they had established in Oz. They helped all of them

to understand that although people have many similar

needs, everybody has unique potential and that health

and well-being depend on all people having the chance to

develop their potential. The rules and structures of the

land have to encourage and enable occupation that has

meaning and value to individuals and communities and

health and well-being are more important than economic

growth, but economic growth depends on the health,

well-being and occupational satisfaction of the people.

Steps were taken to change existing values and structures

so that people were encouraged to aim towards their

occupational potential. Gradually, the sick lists became

smaller and the people were happier. The King was so

impressed that he decreed the land would henceforth be

known as the Kingdom of Op (the Land of Occupational

Potential) and he presented Oscie and Ottie with the

keys to the Kingdom.

At the end of this paper I will share an update of that

fairy story with another piece of occupational science fic-

tion that relates directly to a balance of doing, being and

becoming.

I believe the concept of occupation is very complex

and that it can and must be described in many different

ways by the profession within which it is so central that it

provides its name. A simple way to describe it that

appears to appeal to a wide range of people is to talk

about occupation as a synthesis of doing, being and

becoming. Additionally, consideration of this synthesis

points out some important issues for us to keep in mind

and some directions for future practice. I will start the

process by considering doing, being and becoming as indi-

vidual concepts so that it is possible to appreciate the syn-

thesis more clearly.

DOI NG

Doing is so important that it is impossible to envisage the

humans without it.

People spend their lives almost constantly engaged in

purposeful doing even when free of obligation or neces-

sity. They do daily tasks including things they feel they

must do, and others that they want to. Human evolution

has been filled with ongoing and progressive doings,

which, apart from enabling the species to survive, has

stimulated, entertained and excited some people and

bored, stressed, alienated or depressed others according

to what was done (Wilcock, 1998).

In a case study about occupational change in early

retirement by Kendall (1998), the subject was reported as

saying:

You do get satisfaction, peace of mind, happiness and all

those things from doing what you want to do or what you

enjoy doing.

and

I always wanted to do everything and get frustrated if I

cant.

Doing or not doing are powerful determinants of well

being or disease. Florence Nightingale provided an insight

of this when, at the age of 26, she observed that some

women have gone mad for lack of things to do (Wood-

ham-Smith, 1952). Wilson Schaef (1990) points us in a sim-

ilar direction. She says:

just as nature needs balance, people need balance. We

need time to be whole persons, and this means balance

Reflections on doing, being and becoming

3

A human being is multi dimensional. A human doing

may be more like a drawn line than a faceted gem.

Doing provides the mechanism for social inter-

action, and societal development and growth, forming the

foundation stone of community, local and national identity

to the extent of national government or to achieve

international goals (Wilcock, 1998). Anthropologists

describe this unique human trait as culture and suggest:

Humans are different, not so much for what we do

but rather the fact that we can do more or less what we

want. That is what having a highly developed culture

really means (Leakey & Lewin, 1978).

Doing is a word that appears to be gaining popularity

in our profession as one that is synonymous with occupa-

tion. Along with do, it appears in many definitions of

occupation (Nelson, 1988; Clark et al., 1991; Canadian

Association of Occupational Therapists, 1995; Christian-

sen et al., 1995; Kielhofner, 1995). As well as these defini-

tions, McLaughlin Grays (1997) definition of the essence

of occupation includes that it is perceived as doing by

those engaged in it. Despite thinking that it can give a less

than complete idea of the broad concepts that occupation

embraces, I too have used doing to define occupation

because it is a notion that is easy to assimilate. Under my

direction, the Journal of Occupational Science: Australia

marketed football guernseys with the slogan Occupa-

tional scientists study doing, Occupational therapists

enable doing, Together they help the world do better.

And, I recall in the 1970s, the profession marketed T-shirts

emblazoned with Occupational therapists help make

doing possible. Such slogans and the professions litera-

ture tend to suggest that doing per se is good for health

and, indeed, it is doing that exercises, maintains and

develops physical and mental capacities on which health is

dependent.

In addition, what people do creates and shapes the

societies in which we live, for good or bad. Our profession

though, optimists that we are, have scant research to date

about how doing may be injurious to health and well-

being, except with regard to work and employment haz-

ards. One can wonder whether this is akin to the medical

profession only researching and writing about what is

good about the medicine they prescribe and ignoring the

detrimental health effects. Surely we need to consider

both if occupational therapists accept that we are con-

cerned with enabling occupation wisely to promote health

and well being.

In the present day there is an imbalance in the experi-

ence of doing, between the haves and the have nots;

between the rich and the poor; between the informed and

the illiterate; and between the employed and the unem-

ployed (Wilcock, 1998). Within the employed population,

for example, time for leisure occupations has decreased

(Schor, 1991) and, in a 1995 article in The Weekend Aus-

tralian newspaper, Gare presented evidence from several

major postindustrial nations that suggests that many

people in paid employment are now expected to do too

much and that health breakdowns from this cause are

increasing. Counter to this present trend, Wilson Schaef

(1990) suggests that:

True passion and doing what is important to us does not

require us to destroy ourselves in the process.

However, people may be doing just that. Our occupa-

tional nature is not only driving us to do too much, it is

leading us to embrace technology with a gay abandon that

may destroy us and the planet unless we start to consider

the consequences of our occupational natures and begin to

recognize the need to be true to our nature as part of the

natural world. With this in mind, I concur with the sugges-

tion put forward by Christiansen and Baum (1997) that

there is something beyond the active or doing process that

defines occupation. I think what is beyond the process is,

at least partly, about self, which brings us to the notion of

being.

BEI NG

In dictionaries, being is described with words such as

existing, living, nature and essence. Maslow (1968)

describes it as the contemplation and enjoyment of the

inner life, which is a different kind of action, antithet-

ical to action in the world. It produces stillness and

cessation of muscular activity. Being in a state of being

needs no future because it is already there. Then, becom-

ing ceases for a moment as one is part of the peak

experiences in which time disappears and hopes are ful-

filled. This view has some similarity to what Hegel, in the

19th century, described when discussing Buddhism as

insichsein, of being-within-self, the essential character

of which is nothing but thought itself in which human

A. A. Wilcock

4

beings can allow themselves to be absorbed and can find

repose (Hodgeson, 1987).

Being is about being true to ourselves, to our nature,

to our essence and to what is distinctive about us to bring

to others as part of our relationships and to what we do.

To be in this sense requires that people have time to dis-

cover themselves, to think, to reflect and to simply exist.

As Kendalls (1998) subject said about occupational

change in early retirement:

you might never get a completely happy balance, but

now I have the time and can think as well as do, Im get-

ting where I want to be.

My thoughts about being have also grown from

hypotheses that exist about the health experiences of

people engaging in occupations based more on natural

biological needs than those that are socioculturally

derived. There is a large body of opinion throughout

recorded history that asserts that, apart from the correc-

tive benefits of recent medical science, people living in a

state of nature were able to enjoy a greater sense of health

and well being than at present and probably had more

time to themselves than we do. One could ask whether

people have changed so much that natural needs are no

longer relevant, but this does not seem to be the case and

many of todays stress-related and degenerative diseases

can be traced to a lack of understanding of our being as

well as our doing needs.

Maslow (1968) prescribed a need to discover our

essential biologically based inner nature, which is easily

overcome by habit, cultural pressure and wrong atti-

tudes. Along the same lines Wilson Schaef (1990) asks:

Do we recognize that time for solitude is just as impor-

tant to our work as keeping informed, preparing reports,

or planning? We have to give ourselves time. We have

to give our ideas time. If we dont neither we nor they can

gently shine (Brenda Uleland), and we cannot hear the

voice of our inner process speaking to us.

She suggests:

Unfortunately, even when others do not demand perfec-

tion of us, we who do too much demand it of ourselves. We

forget that when push comes to shove the only standard of

perfection we have to meet is to be perfectly ourselves.

Whenever we set up abstract, external standards and try

to force ourselves to meet them, we destroy ourselves.

Indeed, we tend to imbue the state of being with the

notions of doing particularly when we use it to describe

occupational roles as in being a parent, being a student,

being a sportsperson or being an occupational therapist.

While the notion of being is important to us in this way,

the cultural drives to do better and better alters ways of

being in particular roles and overwhelms with a huge

range of beings in each of which we are expected to

become perfect.

BECOMI NG

A dictionary meaning of becoming as a noun is as a

coming to be (Landau, 1984). This adds to the notion of

being a sense of future, even though in many ways becom-

ing is dependent on what people do and are in the present

and on our history, in terms of cultural development.

Life is a process. We are a process. Everything that has

happened in our lives is an integral part of our becom-

ing (Wilson Schaef, 1990).

In Kielhofners Health Through Occupation, Fidler

(1983) discusses three aspects of becoming: (i) becoming I;

(ii) becoming competent; and (iii) becoming a social

being. In all these scenarios, becoming holds the notions

of potential and growth, of transformation and self actual-

ization. Indeed, one dictionary defines potential as

capable of being or becoming; ability or talent not yet in

full use (Makins, 1996). Occupational therapists are in the

business of helping people transform their lives by facili-

tating talents and abilities not yet in full use through

enabling them to do and to be. We are part of their

process of becoming and I believe that we should con-

stantly bear in mind the importance of this task. To

achieve well being, individual people or communities need

to be enabled towards what they are best fitted and want

to become.

This puts an onus on our profession not to accept,

without thought, the imperatives put upon us by current

economic-driven health care rationales. For occupational

therapy to become what it has the potential to become,

what it is best fitted to become, means that it has to be

true to itself, to its essence, to its own nature, to the beliefs

that it rests upon. As Wilson Schaef (1990) says:

Trying to be what others want us to be is a form of slow

Reflections on doing, being and becoming

5

torture and certain spiritual death. It is not possible to get

all our definitions from outside and maintain our spiritual

integrity. We cannot look to others to tell us who we are,

give us our validity, give us our meaning, and still have

any idea of who we are. When we look to others for our

identity, we spend most of our time and energy trying to

be who they want us to be.

There is so much substance in the relationship

between occupation and health that has not been consid-

ered or acted upon that there is no need for occupational

therapists to look for our identity outside the very wide

boundaries of our profession or the emerging science that

can inform it. That is, we should not be restricted in our

thinking by medical science, psychology, sociology or

economists views of the world, nor by previous occupa-

tional therapy practice. We should be true to our beliefs,

be prepared to test them, expand them and to articulate a

distinctive view of any issue or situation, because becom-

ing through doing and being is part of daily life for all peo-

ple on earth not just those in hospital or health centre.

No one else has the capacity to know us as well as we can

know ourselves. It is in the awareness of ourselves that

our strengths lie. And awareness of every aspect of our-

selves allows us to become who we are Owning

ourselves is probably the richest goldmine any of us will

ever possess (Wilson Schaef, 1990).

DOI NG, BEI NG AND BECOMI NG

I suggest, then, that a synthesis of doing, being and becom-

ing can help us to clarify important issues, both personally

and as a profession.

At this point I would like to share with you a simple

story that expresses the transformative nature of doing,

being and becoming and that was probably very influential

in my becoming an occupational therapist, although it

started long before I knew of the existence of such a

profession.

My fathers sister, my Aunt Maggie, was born with a

disability. The cause is shrouded in history, but the story

goes that, as an infant, she walked on her toes as a result

of a congenital disorder, had surgery to correct the defect

and became a cripple. That was the term used in those

days. I grew up with it and did not associate it with any-

thing discriminatory or stigmatizing, but for those around

her and, indeed, for Maggie herself, her being was that of

a cripple. Maggie, whose eyesight was also poor, had spent

much of her childhood in and out of hospitals and had

little chance to make friends, develop skills or for formal

education. She was poor at reading and writing and spent

most of her early to middle adult life with her mother, my

grandmother.

Maggie walked with crutches or manipulated a self-

propelled wheelchair, which I recall had a great bar on the

back and on which two or three children (like me) could

stand as Maggie sped down hills after Sunday school. We

had many spills, but it was such fun for all of us. I think

that was the time that she had fun in her life.

During the 1930s my parents married and, I am told,

that my mother recognized that Maggie, her new sister-in-

law, needed an interest outside preparing the vegetables,

washing up or gossiping with Grandmas friends. She

taught her to knit. If my mother had known how, it could

have been clog making for profit or book-keeping or any

other occupation. By chance and the right intent, my

mother enabled Maggie to engage in an occupation that

provided meaning and purpose. When I knew her, Maggie

knitted all the time. Mainly, she knitted for other people:

for me or my brother, for my dolls, for other children, for

relatives or socks for soldiers (her war effort). In doing

this occupation, in which she developed great skill, her

crippled being was subtly altered. She did for others. She

became an occupational being, rather than an occupation-

ally deprived being. She became a person in her own right.

The imbalance between her doing and being had inhibited

her becoming a contributing social being. Maggie had had

too much time for being, being a cripple, and not enough

for doing, especially for doing for others.

To provide some recent professional and personal

reflections on doing, being and becoming, I asked a group

of research Masters students at the University of South

Australia for their views. One, who works as a senior occu-

pational therapist in aged care, said:

my life is full of doing, days filled with purpose and

meaning In part it is due to the circumstances of my

life, family, work, friends and community involvements. It

is also an attitude, integral to my being, which has

allowed me to embrace many experiences and opportuni-

ties which have taken me beyond where I have felt com-

fortable and secure. In so doing I have learnt so much

more about what I can be and who I can become. Yet I

often feel that I am not in control of my life as the doing

A. A. Wilcock

6

becomes all consuming of my time and energies

Being makes me think of the present For me it is a

mental and spiritual experience of allowing myself to

withdraw from engagement in activity, to mentally step

back and allow myself to experience in a much fuller way,

the present moment Maybe I need to be more aware

of the being so that I can become more reflective of the

doing and its impact on the becoming (V. Pols, pers.

comm., 1998).

Some of the students found this process fascinating. I

hope you, too, will reflect on doing, being and becoming in

your own lives, as I have found this to be useful for myself

and for considering the potential of the profession.

Indeed, in this way, I have reflected on the professions

doing, being and becoming from its 20th century genesis

and through my personal experience of it in the 40 years

since I commenced as a student. My reflections led to the

belief that we are in a rut, a valuable rut, but a rut for all

that. We are not alone. Every other profession is in a rut

too. The ruts are made of professional habits. They are

well worn and comfortable. They do not necessarily follow

beliefs, for if ruts are followed long enough, beliefs

become hidden in the dust and are eventually lost, except

to rhetoric. Professions are kept in their ruts by social

expectations, by the media and, today especially, by the

dominance of managerial and fiscal policies. For long-

established professions this is, perhaps, acceptable but, for

one as young as ours, still trying to explore its potential,

the rut is inhibiting our becoming what we have the poten-

tial to become. In limiting our doing to what is expected

and deemed as necessary by resource managers who have

not undertaken a course of study towards the set of beliefs

that we hold is to accept that their beliefs are more impor-

tant than ours or that ours are not worth fighting for.

Many papers from around the world presented at the

Montreal Congress of the World Federation of Occupa-

tional Therapists belie such a proposition. They are,

instead, testament to the dedication of our profession to a

set of beliefs that are distinctive to us. The papers also

demonstrate that, in order to work according to our

beliefs, persistence, ingenuity and adaptation is often

required because the way we want to progress is blocked

by policy, resources or the ideas of others.

So, let us consider our comfortable rut. Just as for

other professions, our track gets worn and rutted along the

lines that we take most often. Early in the piece we took a

remedial and craft-orientated rut, then about half-way

through our journey we made the transition to another rut

on the track called activities of daily living (ADL). There

are a few smaller ruts in which others travel. They are

good ruts: all of them, even the crafty one, because they

are all about one aspect or other of this very important

concept of humans as occupational beings, which is so lit-

tle understood in the modern world; what I believe to be

our main track; our different and distinctive track; the

track along which we can offer something of immense

value to the world at large.

Imagine a track, the track to becoming what we have

the potential to become. I suspect that no one reading

this paper believes we have got there or even remotely

near there. Too often the cry is heard people dont

know what we do or we must market the profession

better. To establish a notion of what the track looks like, I

go back to the visions of the founders. I would like you to

recall the objectives of the first National Society for the

Promotion of Occupational Therapy in the USA drawn up

in 1917. They were:

the advancement of occupation as a therapeutic

measure;

the study of the effect of occupation upon the human

being;

and the scientific dispensation of this knowledge

(AOTA, 1967).

We got in a rut almost immediately, the rut called the

advancement of occupation as a therapeutic measure, and

I think that, over time, we have largely lost sight of the

broad track. Many, such as Reilly and Yerxa, have called

us back to it, and I know of therapists who are desperate

to tread it, especially in recent years, but the rut is so deep

now that its hard to get out of it. We know the way of our

rut and others expect us to be in it. They dont expect us to

talk about what the track is about or where it is going.

And we dont. We talk about that part within our rut. I

hear many more people talking about personal indepen-

dence as our central belief (the deepest rut) than about

occupation as an agent of health and well being (the main

track). We will never reach our potential while we travel

only in familiar time- and work-worn, albeit important,

ruts. Without knowing where the track could lead we are

doing without becoming what we have the potential to

become. We are not being ourselves.

The objectives suggest that our founders saw the pro-

fession developing a unique or distinctive occupational

Reflections on doing, being and becoming

7

perspective that would follow a track that could be useful

to all people, not just those in medical care. With this in

mind, I would like to consider a broad track of health and

occupation that incorporates the notions of doing well,

well-being and becoming healthy through satisfying partic-

ipation in occupation.

DOI NG, BEI NG AND BECOMI NG I N

TERMS OF ECOLOGI CAL AND GLOBAL

CONCERNS AND TOWARDS SOCI AL

CHANGE FOR HEALTHI ER LI FESTYLES

An occupational view of health can encompass the rela-

tionship between doing well, well-being and becoming

healthy at cellular to global, biological to socio-cultural

and microscopic to macroscopic levels. This is so because

doing, being and becoming affects health on an individual

basis through the integrative systems of the organism, on a

social level through shared activity, the continuous growth

of occupational technology and socio-political activity and

on a global level through occupational development

affecting the natural resources and ecosystems. Any or all

of these can have negative or positive effects on health

and all are inextricably linked. This fits well with World

Health Organization (WHO) views about health.

Many occupational therapists consider that their role

extends to the promotion of optimal states of health in

line with WHO philosophies, such as that of the 1986

Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO et al., 1986).

This primary source of contemporary health directions

argues for us to take care of each other, our communi-

ties and our natural environment. It also recognizes the

benefits of occupation. Health, it states, is created and

lived by people within the settings of their everyday life;

where they learn, work, play and love and that:

to reach a state of complete physical, mental and

social well-being, an individual or group must be able to

identify and to realize aspirations, to satisfy needs, and to

change or cope with the environment (WHO et al.,

1986).

Now is an opportunity for our profession to reassert its

primary values loudly and widely. We are in tune with the

espoused philosophies of the WHO, but I suspect they

dont know that because we havent told them or anyone

else for that matter, at least not in those particular terms,

and because we are in that RUT.

But what about the ecology? It seems a long way from

our personal independence rut, but not, I think, from con-

sidering health from an occupational point of view.

Indeed, Meyer (1922) talked about humans as active

beings who maintain and balance themselves by living in

harmony with their own nature and the nature about

them. An ecological model of health, the promotion of

healthy relationships between humans, other living organ-

isms, their environments, habits, and modes of life, is per-

haps, the least understood and the most vital in terms of

the long-term health of all. And consider, human occupa-

tion has been the primary force in ecological degradation.

Experts in understanding the occupational nature of

humans need, as soon as possible, to focus on how people

can meet their creative potentials, their need to do, to be

and to become without damaging the environment. Gov-

ernments will require help to understand the importance

of the human need for occupation in such a way that will

maintain natural environments yet will provide sufficient

challenge to peoples capacities and potential so that indi-

viduals and communities can flourish as an integrated part

of the ecology. We dont want people to say of us that:

We have reneged on our responsibility to this society and

this planet. It is time that we courageously put our

thoughts, ideas, and values out there and let them stand

for themselves (Wilson Schaef, 1990).

Let us now consider in terms of current practice doing,

being and becoming in occupational therapy philosophy,

process and outcomes and education.

Despite much current rhetoric, I believe that many

occupational therapists are still not acting on the concept

of enabling occupation (doing, being and becoming)

favouring, instead, techniques, splints and aids to daily liv-

ing. While these can be valuable adjuncts to what we offer,

by focusing on these we have failed to include in, or dis-

card from, our professional repertoire much that is power-

ful in terms of peoples real lives, their health, their

well-being and in terms of them becoming. That may seem

somewhat harsh, but I have another tale.

This is about my mother. On top of two knee replace-

ments, at 85, some 4

1

2 years ago, she had a stroke. Because

the damage was primarily in the left posterior occipital

region, her major presenting feature was right homony-

mous hemianopia, with some visuospatial disorder and

A. A. Wilcock

8

dysphasia. She did not have hemiplegia and looked physi-

cally capable. During her rehabilitation, the occupational

therapists assessed that she could take a shower indepen-

dently. She refused to make a cup of tea if they were not

going to share it with her and they did not pursue that

assessment. This assessment did not uncover what was

probably, in my evaluation, a gross ideational apraxia that,

when coupled with her visual and dysphasic problems,

resulted in her being a-occupational for approximately 2

years. She could not read nor make sense of television,

could not put together an edible meal by herself, although

she did try (her chocolate and mintie-flavoured casseroles

were quite sensational), and she did not make a cup of tea

by herself for years. My mother, quite simply, could not

do without someone doing with her, guiding and select-

ing according to what had meaning for her, except for

sweeping and what I called tissue tying. This entailed

tearing tissues into strips, tying them together into long

bandages and binding up whatever part of her was feeling

pain. It was an intricate and very time-consuming occupa-

tion that was very inward looking that was trying to stop

the pain of not being what she had been. She had ceased

to be her. With her doing gone, so had her being. She

became depressed.

After falling, she was hospitalized, thought she had

been put in a home, gave up and came very close to

death. The gerontologist thought she should not return to

her home, but finally agreed to let us try with some help

from a carer: 5 h/week to help her shower, get up and go

back to bed. In line with the health care system in South

Australia, the occupational therapist assessed her home

and recommended rails in the bathroomand a raised toilet

seat. Hygiene is more valued by the system than enabling

occupation with meaning, other than personal indepen-

dence. I visit every day and my mother spends each week-

end with us but, as I have a pretty busy life, I decided we

should pay her carer to come more often to help her do.

The carer is a registered nurse. She spends an extra couple

of hours each weekday working in the house or the garden

with my mother, helping with her meals and sometimes

taking her out. The carer does this so well that my mother

thinks she is responsible for the immaculate garden, the

clean and shining house, that she is totally independent

and that the carer comes simply to spend time with her

because she likes her and is her friend.

My mothers repertoire of independent occupations

has increased, including showing off her home to all and

sundry with great pride. She no longer ties tissues. Her

health and well being have improved to such an extent

that, at 89, she is now once more a being at peace with her

nature, she does and she is still becoming.

There is a moral to this story that is illustrative of the

rut I talked about earlier. I think that great skill is

required to do the job the carer does with my mother. She

enables my mother to be an occupational being in a way

that no amount of being able to sit on the toilet indepen-

dently will do. I am not implying that independent self

care is not also important, but that we have not put up a

good enough fight for the basic business of our profession,

which surely is about that meaningful occupation: doing

well, well being and becoming what people are best fitted

to become is essential to health.

We can get so involved in a new technique that the tech-

nique itself becomes another monster in our lives and we

become slaves to it (Wilson Schaef, 1990).

There is, however, renewed interest in occupation as

the basis of our profession and this has led some occupa-

tional therapists to engage in research from an occupa-

tional perspective. Cherie Archer, another Masters

student at the University of South Australia, who practises

in neurological rehabilitation, is a case in point. She has

just completed a study using focused ethnography to

explore the occupational sequelae of apraxia. She took as

one aspect of the conceptual framework of her study that

it is through doing that humans become what they

have the capacity to be (Archer, 1998). Both her prac-

tice and assessment methods have changed as a result of

her study.

From this and other studies along similar lines, I am

left with the impression that evaluation of a clients per-

ceptions of their doing, being and becoming should

become part of standard practice. Indeed, Kendalls sub-

ject said of the in-depth interview process:

It has helped me to be able to express how I feel and

what I am doing better I think. In actual fact, having

these sorts of deep conversations I find really fascinating.

I get quite a buzz out of it. I can think deep down and it

all comes out (Kendall, 1998).

These reflections on graduate student research led to a

brief mention of doing, being and becoming for student

teaching and learning. During the past year I have found

that students respond well to the concept of doing, being

Reflections on doing, being and becoming

9

and becoming as ingredients of occupation. The concept

of occupation is complex, and these three words have

helped first year students come to grips with many of the

complexities in a deeper way than discussing work, rest or

play has done in the past. Fourth year students embraced

the notion so strongly that a group of them had T-shirts

made emblazoned with doing, being and becoming that

they wore at the final year conference that marks their

transition from student to professional. I, too, have such a

T-shirt.

CONCLUSI ONS

I love being an occupational therapist, but I would like

our profession to not only work with people with stroke,

hand injury, schizophrenia, developmental delay or cere-

bral palsy, for example, but also with those suffering from

disorders of our time, such as occupational deprivation,

occupational alienation, occupational imbalance and occu-

pational injustice. I believe that such a profession would

enable occupation for personal well being, for community

development, to prevent illness and towards social justice

and a sustainable ecology. In order for us to achieve this,

we have to appreciate that our profession embraces a

unique understanding of occupation that includes all the

things that people do, the relationship of what they do

with who they are as human beings and that through occu-

pation they are in a constant state of becoming different.

To assist this process, in the present paper I have dis-

cussed doing, being and becoming and reflected on the

need for a dynamic balance between them from an indi-

vidual wellness to a professional growth perspective. I

have suggested that, in combination, doing, being and

becoming are integral to health and well being for every-

one and to occupational therapy philosophy, process and

outcomes, because together they epitomise occupation.

With this trilogy in mind, I believe our profession could

reach its potential to enable people in all walks of life,

across the globe, to achieve health through occupation.

I will finish, as I promised, with a second piece of occu-

pational science fiction, the central character being based

on a graduate student.

Once upon a time, in the land of OP, there lived an occu-

pational therapist called Ocimbalans. You will recall that

he had once been a supervisor for King Oczomby, helping

to make sure that all the people obeyed and valued the

rules of the land according to the economic growth of the

country. Ocimbalans had been so impressed by the health

benefits facilitated by Oscie, an occupational scientist,

and Ottie, an occupational therapist, that he determined

to become an occupational therapist himself. So enam-

oured was he of his new calling that, apart from helping

others to reach their occupational potential, he couldnt

stop trying to reach his own.

He was on the go, busily doing all hours of the day and

night. Ocimbalans sought personal meaning in his work

for a pharmaceutical company, putting in many extra

hours as he went from community to community demon-

strating the value of the companys products for people

with occupational dysfunction. He took up graduate stud-

ies on top of his heavy work commitments, as well as

office in the local occupational therapy association, to

which he was very committed. He also tried to ensure

that his social responsibilities were carried out with flair,

so that any anniversary or special occasion was marked

with a function, which of course he arranged bigger,

brighter and different from any other. In his personal life,

too, he had many interests, such as keeping up his health

and fitness regimens and playing sport. This summer, on

top of everything else, he and his wife built their own

swimming pool.

Because he was so busy doing, Ocimbalans was always

late for appointments, he missed some classes altogether

and his assignments were submitted later and later. He

always apologised though, on his mobile phone, as he

raced from venue to venue, enthusiasm high, never saying

no, always doing and always out of breath, but unable to

stop. He never questioned his state of occupational well

being, for hadnt he learned that if his occupations had

meaning his health and well-being would flourish?

As part of his graduate studies with Oscie, the occupa-

tional scientist, he began to be challenged about the place

of being in his life and in the lives of those he advised.

Being he learnt was about being true to himself, about

having time to reflect, to simply exist as part of the nat-

ural world. He was asked how he tempered doing with

time for being. He began to understand that simply

striving for a balance of doing between work, leisure and

social occupations was not conducive to him becoming

what he was best fitted to become. He needed to balance

time for doing with time for being.

Ocimbalans, as you expect, adopted these new-found

ideas with enthusiasm. Always one to do things bigger

A. A. Wilcock

10

and better than others, he set up a DBB Wellness Centre

for the community and sought and obtained help from

the King for resources. The results of the centre, and the

research it carried out, was featured as stories and docu-

mentaries on all television stations in Op and Ocimbalans

became a star. His stardom influenced the young people

of Op, who strove to change their own lives to his cool

concept of doing, being and becoming. Its popular image

ensured that it became part of Ops occupational policy

towards health and wellness for all.

Ref erences

American Occupational Therapy Association. (1967).

Certificate of Incorporation of the National Society for

the Promotion of Occupational Therapy, Inc. Then and

now: 191767. American Occupational Therapy Associ-

ation.

Archer, C. (1998). Towards an occupational understanding

of apraxia. Unpublished Masters thesis. University of

South Australia, Adelaide, South Australia.

Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. (1995).

Guidelines for the client centred practice of occupational

therapy. Toronto, ON: CAOT Publications ACE.

Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. (1997).

Enabling Occupation: An occupational Therapy Per-

spective. Toronto, ON: CAOT Publications ACE.

Christiansen, C. & Baum, C. (1997). Occupational Ther-

apy: Enabling Function and well-being. Thorofare, NJ:

Slack Inc.

Christiansen, C., Clark, F., Kielhofner, G. & Rogers, J.

(1995). Position paper: Occupation. American Journal

of Occupational Therapy, 49, 10151018.

Clark, F., Parham, D., Carlson, M. et al. (1991). Occupa-

tional science: Academic innovation in the service of

occupational therapys future. American Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 45, 300310.

Fidler, G. (1978). Doing and becoming: Purposeful action

and self actualisation. American Journal of Occupa-

tional Therapy, 32, 305310.

Fidler, G. (1983). Doing and becoming: The occupational

therapy experience. In: Kielhofner G. (Ed.). Health

Through Occupation: Theory and Practice in Occupa-

tional Therapy. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Co.

Gare, S. (1995, 8 April). The age of overwork. The Week-

end Australian Review, pp. 23.

Hodgeson, P. C. (Ed.). (1987). Hegel Lectures on the

Philosophy of Religion: Vol. II. Determinate Religion.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kendall, A. (1998). An exploration of change in occupa-

tion following early retirement: Janes early retirement,

a case study. Unpublished Masters thesis. University of

South Australia, Adelaide, South Australia.

Kielhofner, G. (1995). A Model of Human Occupation:

Theory and Application (2nd edn). Baltimore: Williams

and Wilkins.

Krell, D. F. (Ed.). (1993). Basic Writings: Martin Heideg-

ger. London: Routledge.

Landau, S. I. (Ed.). (1984). Funk and Wagnalls Standard

Desk Dictionary. USA: Harper & Row Publishers Inc.

Leakey, R. & Lewin, R. (1978). People of the Lake. Man:

His Origins, Nature, and Future. New York: Penguin

Books.

McLaughlin Gray, J. (1997). Application of the phenom-

enological method to the concept of occupation. Jour-

nal of Occupational Science: Australia, 4, 517.

Makins, M. (Ed.). (1996). Collins Paperback English Dic-

tionary. UK: Collins Publishers.

Maslow, A. (1968). Towards a Psychology of Being (2nd

edn). New York: D. Van Nostrand Co.

Meyer, A. (1922). The philosophy of occupational therapy.

Archives of Occupational Therapy, 1, 110.

Nelson, D. (1988). Occupation: Form and performance.

American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 42,

633641.

Norton, A. (Ed.). (1995). The Hutchinson Dictionary of

Ideas. Oxford: Helicon.

Rowles, G. (1991). Beyond performance: Being in place as

a component of occupational therapy. American Jour-

nal of Occupational Therapy, 45 (3), 265271.

Schor, J. (1991). The Overworked American: The Unex-

pected Decline of Leisure. New York: Basic Books.

Wilcock, A. A. (1998). An Occupational Perspective of

Health. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Inc.

Wilson Schaef, A. (1990). Meditations for Women Who Do

Too Much. New York: Harper Collins.

Woodham-Smith, C. (1952). Florence Nightingale. Lon-

don: The Reprint Society.

World Health Organization, Health and Welfare Canada,

Canadian Public Health Association. (1986). The

Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Ottawa, Canada.

Reflections on doing, being and becoming

11

You might also like

- Rheumatology Practice in Occupational Therapy: Promoting Lifestyle ManagementFrom EverandRheumatology Practice in Occupational Therapy: Promoting Lifestyle ManagementLynne GoodacreNo ratings yet

- Aus Occup Therapy J - 2002 - Wilcock - Reflections On Doing Being and BecomingDocument11 pagesAus Occup Therapy J - 2002 - Wilcock - Reflections On Doing Being and BecomingMelissa CroukampNo ratings yet

- Occupation in Occupational Therapy PDFDocument26 pagesOccupation in Occupational Therapy PDFa_tobarNo ratings yet

- The Occupational Brain A Theory of Human NatureDocument6 pagesThe Occupational Brain A Theory of Human NatureJoaquin OlivaresNo ratings yet

- Fisher (2013) Occupation-Centred Occupation-Based Occupation-FocusedDocument12 pagesFisher (2013) Occupation-Centred Occupation-Based Occupation-FocusedElianaMicaela100% (1)

- Occupational Therapy in Pain ManagementDocument26 pagesOccupational Therapy in Pain ManagementNoor Emellia JamaludinNo ratings yet

- A Review of Oppositional Defiant and Conduct DisordersDocument9 pagesA Review of Oppositional Defiant and Conduct DisordersStiven GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Occupational Therapy As A Major Activity of Human Being: by Rafia KhalidDocument20 pagesOccupational Therapy As A Major Activity of Human Being: by Rafia Khalidnomi9818No ratings yet

- PANat - Thetrical - Air Splints - Talas Pneumaticas Margaret JohnstoneDocument44 pagesPANat - Thetrical - Air Splints - Talas Pneumaticas Margaret JohnstonePedro GouveiaNo ratings yet

- Opening A Private Practice in Occupational Therapy: Earn .1 Aota CeuDocument9 pagesOpening A Private Practice in Occupational Therapy: Earn .1 Aota CeuRey John MonjeNo ratings yet

- Occupational Identity Disruption After Traumatic Brain Injury - An Approach To Occupational Therapy Evaluation and TreatmentDocument13 pagesOccupational Identity Disruption After Traumatic Brain Injury - An Approach To Occupational Therapy Evaluation and Treatmentapi-234120429No ratings yet

- StrokeDocument5 pagesStrokeapi-261670650No ratings yet

- Working As An Occupational Therapist in Another Country 2015Document101 pagesWorking As An Occupational Therapist in Another Country 2015RLedgerdNo ratings yet

- OT and Eating DysfunctionDocument1 pageOT and Eating DysfunctionMCris EsSemNo ratings yet

- 2 Introduction To TheoryDocument14 pages2 Introduction To TheoryNurul Izzah Wahidul AzamNo ratings yet

- History of OT Infographic TimelineDocument1 pageHistory of OT Infographic TimelineAddissa MarieNo ratings yet

- Group Dynamics NotesDocument25 pagesGroup Dynamics NotesVIJAYA DHARSHINI M Bachelor in Occupational Therapy (BOT)No ratings yet

- MOHOST InformationDocument1 pageMOHOST InformationRichard FullertonNo ratings yet

- Strategies Used by Occupational Therapy To Maximize ADL IndependenceDocument53 pagesStrategies Used by Occupational Therapy To Maximize ADL IndependenceNizam lotfiNo ratings yet

- Instrumental Activities Daily Living: Try ThisDocument11 pagesInstrumental Activities Daily Living: Try ThisbalryoNo ratings yet

- Occupational Therapy and Mental Health 1Document18 pagesOccupational Therapy and Mental Health 1Roman -No ratings yet

- Cognition, Cognitive Rehabilitation, and Occupational PerformanceDocument23 pagesCognition, Cognitive Rehabilitation, and Occupational PerformanceMaria AiramNo ratings yet

- Occupational AdaptationDocument5 pagesOccupational AdaptationVASH12345100% (1)

- Guidelines For Documentation of Occupational Therapy PDFDocument7 pagesGuidelines For Documentation of Occupational Therapy PDFMaria AiramNo ratings yet

- Ot Mental Health NutritionDocument11 pagesOt Mental Health Nutritionapi-340399319No ratings yet

- Functional AssesmentDocument22 pagesFunctional AssesmentHeri WibisonoNo ratings yet

- Eval Soap Note 2Document9 pagesEval Soap Note 2api-435763096No ratings yet

- Program ProposalDocument17 pagesProgram Proposalapi-582621575No ratings yet

- The Application of Assessment and Evaluation Procedure in Using Occupation Centered PracticeDocument55 pagesThe Application of Assessment and Evaluation Procedure in Using Occupation Centered PracticeAswathi100% (2)

- Role Checklist With InstructionsDocument8 pagesRole Checklist With InstructionsSze Wing LeeNo ratings yet

- Occupational TherapyDocument13 pagesOccupational TherapyRiris NariswariNo ratings yet

- B. Occupational Therapy (Hons.) : Faculty of Health Sciences Universiti Teknologi MaraDocument3 pagesB. Occupational Therapy (Hons.) : Faculty of Health Sciences Universiti Teknologi MaraSiti Nur Hafidzoh OmarNo ratings yet

- Home Base Intervention OtDocument9 pagesHome Base Intervention OtPaulinaNo ratings yet

- Occt630 Occupational Profile InterventionDocument19 pagesOcct630 Occupational Profile Interventionapi-290880850No ratings yet

- Rehab of Patients With HemiplegiaDocument2 pagesRehab of Patients With HemiplegiaMilijana D. DelevićNo ratings yet

- Occupational TherapyDocument5 pagesOccupational TherapyZahra IffahNo ratings yet

- Clients Goals To Address in SessionDocument8 pagesClients Goals To Address in Sessionapi-436429414No ratings yet

- Model of Human Occupation Parts 1-4Document36 pagesModel of Human Occupation Parts 1-4Alice GiffordNo ratings yet

- Cimt and NDT Proposal-2 AltDocument10 pagesCimt and NDT Proposal-2 Altapi-487111274No ratings yet

- Client-Centered AssessmentDocument4 pagesClient-Centered AssessmentHon “Issac” KinHoNo ratings yet

- Meaningful OccupationDocument13 pagesMeaningful OccupationSyafiq Azzmi100% (1)

- WKST 5 Learning PlanDocument2 pagesWKST 5 Learning Planapi-380681224No ratings yet

- Occupational Justice A Conceptual ReviewDocument14 pagesOccupational Justice A Conceptual ReviewMelissa CroukampNo ratings yet

- Gilfoyle 1984 Slagle LectureDocument14 pagesGilfoyle 1984 Slagle LectureDebbieNo ratings yet

- Model of Human OccupationDocument5 pagesModel of Human OccupationPatrick IlaoNo ratings yet

- Fall Prevention For Older AdultsDocument2 pagesFall Prevention For Older AdultsThe American Occupational Therapy AssociationNo ratings yet

- Vergara, J. - T.O. in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitDocument11 pagesVergara, J. - T.O. in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitFedora Margarita Santander CeronNo ratings yet

- Horak 2006 Postural Orientation and EquilDocument5 pagesHorak 2006 Postural Orientation and EquilthisisanubisNo ratings yet

- Occupational Therapy Practice FrameworkDocument31 pagesOccupational Therapy Practice FrameworkLian Michael0% (1)

- Kristen Kincaid Occupational Analysis & Intervention PlanDocument23 pagesKristen Kincaid Occupational Analysis & Intervention Planapi-282525755100% (1)

- Body Awareness FactsheetDocument2 pagesBody Awareness FactsheetDr.GladsonNo ratings yet

- Artifact 5 Soap NoteDocument3 pagesArtifact 5 Soap Noteapi-517998988No ratings yet

- Soap 11Document4 pagesSoap 11api-436429414No ratings yet

- Position Paper OT For People With LDDocument10 pagesPosition Paper OT For People With LDLytiana WilliamsNo ratings yet

- CC StrokeDocument13 pagesCC Strokeapi-436090845100% (1)

- Aota PDFDocument2 pagesAota PDFJuliana MassariolliNo ratings yet

- Work and Occupational TherapyDocument31 pagesWork and Occupational Therapysmith197077No ratings yet

- Rol Del To en Disfagia OrofaringeaDocument24 pagesRol Del To en Disfagia OrofaringeaMCris EsSemNo ratings yet

- World's Largest Science, Technology & Medicine Open Access Book PublisherDocument17 pagesWorld's Largest Science, Technology & Medicine Open Access Book PublisherValeria Sousa de AndradeNo ratings yet

- Adl & Iadl PresentationDocument52 pagesAdl & Iadl PresentationHemanth S100% (1)

- Brainstem Gliomas in Adults: Prognostic Factors and ClassificationDocument12 pagesBrainstem Gliomas in Adults: Prognostic Factors and ClassificationIsabel PereiraNo ratings yet

- Trail Making TestDocument5 pagesTrail Making TestRahmah Fitri Utami71% (7)

- Specific Language Impairment: A Deficit in Grammar or Processing?Document8 pagesSpecific Language Impairment: A Deficit in Grammar or Processing?Isabel PereiraNo ratings yet

- Ficha de Trabalho - Personal PronounsDocument1 pageFicha de Trabalho - Personal PronounsCarla Vaz LinoNo ratings yet

- 37140999Document6 pages37140999Isabel PereiraNo ratings yet

- 37140999Document6 pages37140999Isabel PereiraNo ratings yet

- Daily RoutineDocument1 pageDaily RoutineIsabel PereiraNo ratings yet

- Scanned ImageDocument56 pagesScanned ImageIsabel PereiraNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson LogDocument4 pagesDaily Lesson LogPhebe Zhie Zhia CampeñaNo ratings yet

- Understanding and Predicting Electronic Commerce Adoption An Extension of The Theory of Planned BehaviorDocument30 pagesUnderstanding and Predicting Electronic Commerce Adoption An Extension of The Theory of Planned BehaviorJingga NovebrezaNo ratings yet

- FLP10037 Japan SakuraaDocument3 pagesFLP10037 Japan SakuraatazzorroNo ratings yet

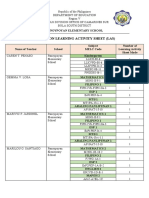

- PANOYPOYAN ES Report On LASDocument4 pagesPANOYPOYAN ES Report On LASEric D. ValleNo ratings yet

- Suckling, ChristopherDocument325 pagesSuckling, ChristopherPatrizia Mandolino100% (1)

- Discussion QuestionsDocument4 pagesDiscussion QuestionsDavid MoonNo ratings yet

- Managing Conflict in WorkplaceDocument5 pagesManaging Conflict in WorkplaceMohd Safayat AlamNo ratings yet

- Varun Sodhi Resume PDFDocument1 pageVarun Sodhi Resume PDFVarun SodhiNo ratings yet

- Natural and Inverted Order of SentencesDocument27 pagesNatural and Inverted Order of SentencesMaribie SA Metre33% (3)

- Coordinate Geometry 2: Additional MathematicsDocument23 pagesCoordinate Geometry 2: Additional MathematicsJoel PrabaharNo ratings yet

- 1 variant. 1. Вставити потрібну форму допоміжного дієслова TO BE в реченняDocument3 pages1 variant. 1. Вставити потрібну форму допоміжного дієслова TO BE в реченняАнастасія КостюкNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive ExaminationDocument4 pagesComprehensive ExaminationAllan WadiongNo ratings yet

- Wheeler'S Cyclic ModelDocument3 pagesWheeler'S Cyclic Modelaly XumairNo ratings yet

- Comm2 Palazzi Et Al TCH Guide To Patient CommunicationDocument269 pagesComm2 Palazzi Et Al TCH Guide To Patient Communicationromeoenny4154No ratings yet

- Table of Specification in Tle 7Document1 pageTable of Specification in Tle 7JhEng Cao ManansalaNo ratings yet

- What Are The Advantages and Disadvantages of Computers?Document4 pagesWhat Are The Advantages and Disadvantages of Computers?Muhammad SajidNo ratings yet

- Grade 10-AGUINALDO: Number of Students by Sitio/PurokDocument3 pagesGrade 10-AGUINALDO: Number of Students by Sitio/PurokKaren May UrlandaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Childhood Cancer On Family FunctioningDocument13 pagesThe Impact of Childhood Cancer On Family Functioningapi-585969205No ratings yet

- Catrina Villalpando ResumeDocument1 pageCatrina Villalpando Resumeapi-490106460No ratings yet

- The Promise of Open EducationDocument37 pagesThe Promise of Open Educationjeremy_rielNo ratings yet

- Activity 4 Written Assessment - BambaDocument3 pagesActivity 4 Written Assessment - BambaMatsuoka LykaNo ratings yet

- 05basics of Veda Swaras and Recital - ChandasDocument18 pages05basics of Veda Swaras and Recital - ChandasFghNo ratings yet

- Becoming Self-Regulated LearnersDocument30 pagesBecoming Self-Regulated LearnersJaqueline Benj OftanaNo ratings yet

- Compatibility SIMOTION V4211Document58 pagesCompatibility SIMOTION V4211Ephraem KalisNo ratings yet

- Nrityagram DocsDocument2 pagesNrityagram DocsSajalSaket100% (1)

- NetflixDocument18 pagesNetflixLei Yunice NorberteNo ratings yet

- CAPE Caribbean Studies Definitions of Important TermsDocument2 pagesCAPE Caribbean Studies Definitions of Important Termssmartkid167No ratings yet

- F240 Early Childhood Education Inners FINAL Web PDFDocument319 pagesF240 Early Childhood Education Inners FINAL Web PDFSandra ClNo ratings yet

- Hanns Seidel Foundation Myanmar Shades of Federalism Vol 1Document84 pagesHanns Seidel Foundation Myanmar Shades of Federalism Vol 1mercurio324326100% (1)

- Learning Experience Plan SummarizingDocument3 pagesLearning Experience Plan Summarizingapi-341062759No ratings yet

- An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyFrom EverandAn Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- The Complex PTSD Workbook: A Mind-Body Approach to Regaining Emotional Control & Becoming WholeFrom EverandThe Complex PTSD Workbook: A Mind-Body Approach to Regaining Emotional Control & Becoming WholeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (49)

- My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesFrom EverandMy Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (70)

- Rewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and WorryFrom EverandRewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and WorryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (157)

- The Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a TimeFrom EverandThe Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a TimeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (140)

- Summary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDFrom EverandSummary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (167)

- Vagus Nerve: A Complete Self Help Guide to Stimulate and Activate Vagal Tone — A Self Healing Exercises to Reduce Chronic Illness, PTSD, Anxiety, Inflammation, Depression, Trauma, and AngerFrom EverandVagus Nerve: A Complete Self Help Guide to Stimulate and Activate Vagal Tone — A Self Healing Exercises to Reduce Chronic Illness, PTSD, Anxiety, Inflammation, Depression, Trauma, and AngerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (16)

- Rapid Weight Loss Hypnosis: How to Lose Weight with Self-Hypnosis, Positive Affirmations, Guided Meditations, and Hypnotherapy to Stop Emotional Eating, Food Addiction, Binge Eating and MoreFrom EverandRapid Weight Loss Hypnosis: How to Lose Weight with Self-Hypnosis, Positive Affirmations, Guided Meditations, and Hypnotherapy to Stop Emotional Eating, Food Addiction, Binge Eating and MoreRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (17)

- The Worry Trick: How Your Brain Tricks You into Expecting the Worst and What You Can Do About ItFrom EverandThe Worry Trick: How Your Brain Tricks You into Expecting the Worst and What You Can Do About ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (107)

- Somatic Therapy Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Experiencing Greater Mind-Body ConnectionFrom EverandSomatic Therapy Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Experiencing Greater Mind-Body ConnectionNo ratings yet

- Don't Panic: Taking Control of Anxiety AttacksFrom EverandDon't Panic: Taking Control of Anxiety AttacksRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER: Help Yourself and Help Others. Articulate Guide to BPD. Tools and Techniques to Control Emotions, Anger, and Mood Swings. Save All Your Relationships and Yourself. NEW VERSIONFrom EverandBORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER: Help Yourself and Help Others. Articulate Guide to BPD. Tools and Techniques to Control Emotions, Anger, and Mood Swings. Save All Your Relationships and Yourself. NEW VERSIONRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (24)

- Brain Inflamed: Uncovering the Hidden Causes of Anxiety, Depression, and Other Mood Disorders in Adolescents and TeensFrom EverandBrain Inflamed: Uncovering the Hidden Causes of Anxiety, Depression, and Other Mood Disorders in Adolescents and TeensRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Summary: No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model by Richard C. Schwartz PhD & Alanis Morissette: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model by Richard C. Schwartz PhD & Alanis Morissette: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- Binaural Beats: Activation of pineal gland – Stress reduction – Meditation – Brainwave entrainment – Deep relaxationFrom EverandBinaural Beats: Activation of pineal gland – Stress reduction – Meditation – Brainwave entrainment – Deep relaxationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (9)

- A Profession Without Reason: The Crisis of Contemporary Psychiatry—Untangled and Solved by Spinoza, Freethinking, and Radical EnlightenmentFrom EverandA Profession Without Reason: The Crisis of Contemporary Psychiatry—Untangled and Solved by Spinoza, Freethinking, and Radical EnlightenmentNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsFrom EverandCritical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (39)

- Heal the Body, Heal the Mind: A Somatic Approach to Moving Beyond TraumaFrom EverandHeal the Body, Heal the Mind: A Somatic Approach to Moving Beyond TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (56)

- Winning the War in Your Mind: Change Your Thinking, Change Your LifeFrom EverandWinning the War in Your Mind: Change Your Thinking, Change Your LifeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (558)

- Redefining Anxiety: What It Is, What It Isn't, and How to Get Your Life BackFrom EverandRedefining Anxiety: What It Is, What It Isn't, and How to Get Your Life BackRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (152)

- When Religion Hurts You: Healing from Religious Trauma and the Impact of High-Control ReligionFrom EverandWhen Religion Hurts You: Healing from Religious Trauma and the Impact of High-Control ReligionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- I Don't Want to Talk About It: Overcoming the Secret Legacy of Male DepressionFrom EverandI Don't Want to Talk About It: Overcoming the Secret Legacy of Male DepressionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (106)

- Feel the Fear… and Do It Anyway: Dynamic Techniques for Turning Fear, Indecision, and Anger into Power, Action, and LoveFrom EverandFeel the Fear… and Do It Anyway: Dynamic Techniques for Turning Fear, Indecision, and Anger into Power, Action, and LoveRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (250)