Professional Documents

Culture Documents

HLI v. PARC

Uploaded by

RaffyLaguesma0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

52 views8 pagesconsolidated digest and issues on HLI v. PARC on all three cases decided by the Supreme Court

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentconsolidated digest and issues on HLI v. PARC on all three cases decided by the Supreme Court

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

52 views8 pagesHLI v. PARC

Uploaded by

RaffyLaguesmaconsolidated digest and issues on HLI v. PARC on all three cases decided by the Supreme Court

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

HACIENDA LUISITA V.

PRESIDENTIAL AGRARIAN REFORM COUNCIL

July 5, 2011

FACTS:

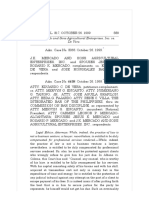

In 1958, the Spanish owners of Compaia General de Tabacos de Filipinas (Tabacalera)

sold Hacienda Luisita and the Central Azucarera de Tarlac, the sugar mill of the hacienda, to the

Tarlac Development Corporation (Tadeco), then owned and controlled by the Jose Cojuangco Sr.

Group. The Central Bank of the Philippines assisted Tadeco in obtaining a dollar loan from

a US bank. Also, the GSIS extended a PhP5.911 million loan in favor of Tadeco to pay the peso

price component of the sale, with the condition that the lots comprising the Hacienda Luisita be

subdivided by the applicant-corporation and sold at cost to the tenants, should there be any, and

whenever conditions should exist warranting such action under the provisions of the Land

Tenure Act. Tadeco however did not comply with this condition.

On May 7, 1980, the martial law administration filed a suit before the Manila RTC

against Tadeco, et al., for them to surrender Hacienda Luisita to the then Ministry of Agrarian

Reform (MAR) so that the land can be distributed to farmers at cost. Responding, Tadeco alleged

that Hacienda Luisita does not have tenants, besides which sugar lands of which the hacienda

consisted are not covered by existing agrarian reform legislations. The Manila RTC rendered

judgment ordering Tadeco to surrender Hacienda Luisita to the MAR. Therefrom, Tadeco

appealed to the CA.

On March 17, 1988, during the administration of President Corazon Cojuangco Aquino,

the Office of the Solicitor General moved to withdraw the governments case against Tadeco, et

al. The CA dismissed the case, subject to the PARCs approval of Tadecos proposed stock

distribution plan (SDP) in favor of its farmworkers. [Under EO 229 and later RA 6657, Tadeco

had the option of availing stock distribution as an alternative modality to actual land transfer to

the farmworkers.] On August 23, 1988, Tadeco organized a spin-off corporation, herein

petitioner HLI, as vehicle to facilitate stock acquisition by the farmworkers. For this purpose,

Tadeco conveyed to HLI the agricultural land portion (4,915.75 hectares) and other farm-related

properties of Hacienda Luisita in exchange for HLI shares of stock.

On May 9, 1989, some 93% of the then farmworker-beneficiaries (FWBs) complement of

Hacienda Luisita signified in a referendum their acceptance of the proposed HLIs Stock

Distribution Option Plan (SODP). On May 11, 1989, the SDOA was formally entered into by

Tadeco, HLI, and the 5,848 qualified FWBs. This attested to by then DAR Secretary Philip

Juico. The SDOA embodied the basis and mechanics of HLIs SDP, which was eventually

approved by the PARC after a follow-up referendum conducted by the DAR on October 14,

1989, in which 5,117 FWBs, out of 5,315 who participated, opted to receive shares in HLI.

On August 15, 1995, HLI applied for the conversion of 500 hectares of land of the

hacienda from agricultural to industrial use, pursuant to Sec. 65 of RA 6657. The DAR approved

the application on August 14, 1996, subject to payment of three percent (3%) of the gross selling

price to the FWBs and to HLIs continued compliance with its undertakings under the SDP,

among other conditions.

On December 13, 1996, HLI, in exchange for subscription of 12,000,000 shares of stocks

of Centennary Holdings, Inc, ceded 300 hectares of the converted area to the latter.

Subsequently, Centennary sold the entire 300 hectares for PhP750 million to Luisita Industrial

Park Corporation (LIPCO), which used it in developing an industrial complex. From this area

was carved out 2 parcels, for which 2 separate titles were issued in the name of LIPCO. Later,

LIPCO transferred these 2 parcels to the Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation (RCBC) in

payment of LIPCOs PhP431,695,732.10 loan obligations to RCBC. LIPCOs titles were

cancelled and new ones were issued to RCBC. Apart from the 500 hectares, another 80.51

hectares were later detached from Hacienda Luisita and acquired by the government as part of

the Subic-Clark-Tarlac Expressway (SCTEX) complex. Thus, 4,335.75 hectares remained of the

original 4,915 hectares Tadeco ceded to HLI.

Such, was the state of things when two separate petitions reached the DAR in the latter

part of 2003. The first was filed by the Supervisory Group of HLI (Supervisory Group), praying

for a renegotiation of the SDOA, or, in the alternative, its revocation. The second petition,

praying for the revocation and nullification of the SDOA and the distribution of the lands in the

hacienda, was filed by AMBALA. The DAR then constituted a Special Task Force (STF) to

attend to issues relating to the SDP of HLI. After investigation and evaluation, the STF found

that HLI has not complied with its obligations under RA 6657 despite the implementation of the

SDP. On December 22, 2005, the PARC issued the assailed Resolution No. 2005-32-01,

recalling/revoking the SDO plan of Tadeco/HLI. It further resolved that the subject lands be

forthwith placed under the compulsory coverage or mandated land acquisition scheme of the

CARP.

From the foregoing resolution, HLI sought reconsideration. HLI also filed a petition

before the Supreme Court in light of what it considers as the DARs hasty placing of Hacienda

Luisita under CARP even before PARC could rule or even read the motion for reconsideration.

PARC eventually denied HLIs motion for reconsideration via Resolution No. 2006-34-01 dated

May 3, 2006.

ISSUES:

1. Whether PARC can revoke or recall HLIs SDP? Is it Valid?

2. Whether Sec. 31 of R.A. 6657 is unconstitutional?

3. Whether the Lands acquired by RCBC and LIPCO are covered by the revocation order of

PARC?

HELD:

1. Yes, PARC has jurisdiction to revoke HLIs SDP under the doctrine of necessary implication.

Under Sec. 31 of RA 6657, as implemented by DAO 10, the authority to approve the plan

for stock distribution of the corporate landowner belongs to PARC. Contrary to petitioner HLIs

posture, PARC also has the power to revoke the SDP which it previously approved. It may be, as

urged, that RA 6657 or other executive issuances on agrarian reform do not explicitly vest the

PARC with the power to revoke/recall an approved SDP. Such power or authority, however, is

deemed possessed by PARC under the principle of necessary implication, a basic postulate that

what is implied in a statute is as much a part of it as that which is expressed.

Following the doctrine of necessary implication, it may be stated that the conferment of

express power to approve a plan for stock distribution of the agricultural land of corporate

owners necessarily includes the power to revoke or recall the approval of the plan. To deny

PARC such revocatory power would reduce it into a toothless agency of CARP, because the very

same agency tasked to ensure compliance by the corporate landowner with the approved SDP

would be without authority to impose sanctions for non-compliance with it.

The revocation of the approval of the SDP is valid: (1) the mechanics and timelines of

HLIs stock distribution violate DAO 10 because the minimum individual allocation of each

original FWB of 18,804.32 shares was diluted as a result of the use of man days and the hiring

of additional farmworkers; (2) the 30-year timeframe for HLI-to-FWBs stock transfer is contrary

to what Sec. 11 of DAO 10 prescribes.

Taking into account the above discussion, the revocation of the SDP by PARC should be

upheld [because of violations of] DAO 10. It bears stressing that under Sec. 49 of RA 6657, the

PARC and the DAR have the power to issue rules and regulations, substantive or

procedural. Being a product of such rule-making power, DAO 10 has the force and effect of law

and must be duly complied with. The PARC is, therefore, correct in revoking the

SDP. Consequently, the PARC Resolution No. 89-12-2 dated November 21, l989 approving the

HLIs SDP is nullified and voided.

2. No, Sec. 31 of RA 6657 is not unconstitutional. The Court actually refused to pass upon the

constitutional question because it was not raised at the earliest opportunity and because the

resolution thereof is not the lis mota of the case. Moreover, the issue has been rendered moot and

academic since SDO is no longer one of the modes of acquisition under RA 9700.

In order for the Court to exercise its power of judicial review over, and pass upon the

constitutionality of, acts of the executive or legislative departments, it does so only when the

following essential requirements are first met, to wit: (1) there is an actual case or controversy;

(2) that the constitutional question is raised at the earliest possible opportunity by a proper party

or one with locus standi; and (3) the issue of constitutionality must be the very lis mota of the

case.

Not all the foregoing requirements are satisfied in the case at bar.

While there is indeed an actual case or controversy, intervenor FARM, composed of a

small minority of 27 farmers, has yet to explain its failure to challenge the constitutionality of

Sec. 31 of RA 6657 as early as November 21, 1989 when PARC approved the SDP of Hacienda

Luisita or at least within a reasonable time thereafter, and why its members received benefits

from the SDP without so much of a protest. It was only on December 4, 2003 or 14 years after

approval of the SDP that said plan and approving resolution were sought to be revoked, but not,

to stress, by FARM or any of its members, but by petitioner AMBALA. Furthermore, the

AMBALA petition did NOT question the constitutionality of Sec. 31 of RA 6657, but

concentrated on the purported flaws and gaps in the subsequent implementation of the SDP.

Even the public respondents, as represented by the Solicitor General, did not question the

constitutionality of the provision. On the other hand, FARM, whose 27 members formerly

belonged to AMBALA, raised the constitutionality of Sec. 31 only on May 3, 2007 when it filed

its Supplemental Comment with the Court. Thus, it took FARM some eighteen (18) years from

November 21, 1989 before it challenged the constitutionality of Sec. 31 of RA 6657 which is

quite too late in the day. The FARM members slept on their rights and even accepted benefits

from the SDP with nary a complaint on the alleged unconstitutionality of Sec. 31 upon which the

benefits were derived. The Court cannot now be goaded into resolving a constitutional issue that

FARM failed to assail after the lapse of a long period of time and the occurrence of numerous

events and activities which resulted from the application of an alleged unconstitutional legal

provision.

It may be well to note at this juncture that Sec. 5 of RA 9700, amending Sec. 7 of RA

6657, has all but superseded Sec. 31 of RA 6657 vis--vis the stock distribution component of

said Sec. 31. In its pertinent part, Sec. 5 of RA 9700 provides: That after June 30, 2009, the

modes of acquisition shall be limited to voluntary offer to sell and compulsory acquisition.

Thus, for all intents and purposes, the stock distribution scheme under Sec. 31 of RA 6657 is no

longer an available option under existing law. The question of whether or not it is

unconstitutional should be a moot issue.

3. Yes, those portions of the converted land within Hacienda Luisita that RCBC and LIPCO

acquired by purchase should be excluded from the coverage of the assailed PARC resolution.

[T]here are two (2) requirements before one may be considered a purchaser in good faith,

namely: (1) that the purchaser buys the property of another without notice that some other person

has a right to or interest in such property; and (2) that the purchaser pays a full and fair price for

the property at the time of such purchase or before he or she has notice of the claim of another.

It can rightfully be said that both LIPCO and RCBC arebased on the above

requirements and with respect to the adverted transactions of the converted land in question

purchasers in good faith for value entitled to the benefits arising from such status.

First, at the time LIPCO purchased the entire three hundred (300) hectares of industrial

land, there was no notice of any supposed defect in the title of its transferor, Centennary, or that

any other person has a right to or interest in such property. In fact, at the time LIPCO acquired

said parcels of land, only the following annotations appeared on the TCT in the name of

Centennary: the Secretarys Certificate in favor of Teresita Lopa, the Secretarys Certificate in

favor of Shintaro Murai, and the conversion of the property from agricultural to industrial and

residential use.

The same is true with respect to RCBC. At the time it acquired portions of Hacienda

Luisita, only the following general annotations appeared on the TCTs of LIPCO: the Deed of

Restrictions, limiting its use solely as an industrial estate; the Secretarys Certificate in favor of

Koji Komai and Kyosuke Hori; and the Real Estate Mortgage in favor of RCBC to guarantee the

payment of PhP 300 million.

To be sure, intervenor RCBC and LIPCO knew that the lots they bought were subjected

to CARP coverage by means of a stock distribution plan, as the DAR conversion order was

annotated at the back of the titles of the lots they acquired. However, they are of the honest

belief that the subject lots were validly converted to commercial or industrial purposes and for

which said lots were taken out of the CARP coverage subject of PARC Resolution No. 89-12-2

and, hence, can be legally and validly acquired by them. After all, Sec. 65 of RA 6657 explicitly

allows conversion and disposition of agricultural lands previously covered by CARP land

acquisition after the lapse of five (5) years from its award when the land ceases to be

economically feasible and sound for agricultural purposes or the locality has become urbanized

and the land will have a greater economic value for residential, commercial or industrial

purposes. Moreover, DAR notified all the affected parties, more particularly the FWBs, and

gave them the opportunity to comment or oppose the proposed conversion. DAR, after going

through the necessary processes, granted the conversion of 500 hectares of Hacienda Luisita

pursuant to its primary jurisdiction under Sec. 50 of RA 6657 to determine and adjudicate

agrarian reform matters and its original exclusive jurisdiction over all matters involving the

implementation of agrarian reform. The DAR conversion order became final and executory after

none of the FWBs interposed an appeal to the CA. In this factual setting, RCBC and LIPCO

purchased the lots in question on their honest and well-founded belief that the previous registered

owners could legally sell and convey the lots though these were previously subject of CARP

coverage. Ergo, RCBC and LIPCO acted in good faith in acquiring the subject lots.

And second, both LIPCO and RCBC purchased portions of Hacienda Luisita for value.

Undeniably, LIPCO acquired 300 hectares of land from Centennary for the amount of PhP750

million pursuant to a Deed of Sale dated July 30, 1998. On the other hand, in a Deed of Absolute

Assignment dated November 25, 2004, LIPCO conveyed portions of Hacienda Luisita in favor

of RCBC by way of dacion en pago to pay for a loan of PhP431,695,732.10.

In relying upon the above-mentioned approvals, proclamation and conversion order, both

RCBC and LIPCO cannot be considered at fault for believing that certain portions of Hacienda

Luisita are industrial/commercial lands and are, thus, outside the ambit of CARP. The PARC,

and consequently DAR, gravely abused its discretion when it placed LIPCOs and RCBCs

property which once formed part of Hacienda Luisita under the CARP compulsory acquisition

scheme via the assailed Notice of Coverage.

While the Court affirms the revocation of the SDP on Hacienda Luisita subject of PARC

Resolution Nos. 2005-32-01 and 2006-34-01, the Court cannot close its eyes to certain

operative facts that had occurred in the interim. Pertinently, the operative fact doctrine

realizes that, in declaring a law or executive action null and void, or, by extension, no longer

without force and effect, undue harshness and resulting unfairness must be avoided. This is as it

should realistically be, since rights might have accrued in favor of natural or juridical persons

and obligations justly incurred in the meantime. The actual existence of a statute or executive act

is, prior to such a determination, an operative fact and may have consequences which cannot

justly be ignored; the past cannot always be erased by a new judicial declaration.

November 22, 2011

ISSUES:

1. Is the date of the taking (for purposes of determining the just compensation payable to

HLI) November 21, 1989, when PARC approved HLIs SDP?

2. Has the 10-year period prohibition on the transfer of awarded lands under RA 6657

lapsed on May 10, 1999?

3. Whether the ruling in the July 5, 2011 Decision that the qualified FWBs be given an

option to remain as stockholders of HLI be reconsidered?

HELD:

1. Yes, the date of taking is November 21, 1989, when PARC approved HLIs SDP.

For the purpose of determining just compensation, the date of taking is November 21,

1989 (the date when PARC approved HLIs SDP) since this is the time that the FWBs were

considered to own and possess the agricultural lands in Hacienda Luisita. To be precise, these

lands became subject of the agrarian reform coverage through the stock distribution scheme only

upon the approval of the SDP, that is, on November 21, 1989. Such approval is akin to a notice

of coverage ordinarily issued under compulsory acquisition. On the contention of the minority

(Justice Sereno) that the date of the notice of coverage [after PARCs revocation of the SDP],

that is, January 2, 2006, is determinative of the just compensation that HLI is entitled to receive,

the Court majority noted that none of the cases cited to justify this position involved the stock

distribution scheme. Thus, said cases do not squarely apply to the instant case. The foregoing

notwithstanding, it bears stressing that the DAR's land valuation is only preliminary and is not,

by any means, final and conclusive upon the landowner. The landowner can file an original

action with the RTC acting as a special agrarian court to determine just compensation. The court

has the right to review with finality the determination in the exercise of what is admittedly a

judicial function.

2. No, the 10-year period prohibition on the transfer of awarded lands under RA 6657 has NOT

lapsed on May 10, 1999; thus, the qualified FWBs should NOT yet be allowed to sell their land

interests in Hacienda Luisita to third parties.

Under RA 6657 and DAO 1, the awarded lands may only be transferred or conveyed after

10 years from the issuance and registration of the emancipation patent (EP) or certificate of land

ownership award (CLOA). Considering that the EPs or CLOAs have not yet been issued to the

qualified FWBs in the instant case, the 10-year prohibitive period has not even started.

Significantly, the reckoning point is the issuance of the EP or CLOA, and not the placing of the

agricultural lands under CARP coverage. Moreover, should the FWBs be immediately allowed

the option to sell or convey their interest in the subject lands, then all efforts at agrarian reform

would be rendered nugatory, since, at the end of the day, these lands will just be transferred to

persons not entitled to land distribution under CARP.

3. Yes, the ruling in the July 5, 2011 Decision that the qualified FWBs be given an option to

remain as stockholders of HLI should be reconsidered.

The Court reconsidered its earlier decision that the qualified FWBs should be given an

option to remain as stockholders of HLI, inasmuch as these qualified FWBs will never gain

control [over the subject lands] given the present proportion of shareholdings in HLI. The Court

noted that the share of the FWBs in the HLI capital stock is [just] 33.296%. Thus, even if all the

holders of this 33.296% unanimously vote to remain as HLI stockholders, which is unlikely,

control will never be in the hands of the FWBs. Control means the majority of [sic] 50% plus at

least one share of the common shares and other voting shares. Applying the formula to the HLI

stockholdings, the number of shares that will constitute the majority is 295,112,101 shares

(590,554,220 total HLI capital shares divided by 2 plus one [1] HLI share). The 118,391,976.85

shares subject to the SDP approved by PARC substantially fall short of the 295,112,101 shares

needed by the FWBs to acquire control over HLI.

April 24, 2012

ISSUES:

1. Whether the homelots distributed to the FWBs require payment to HLI as the landowner?

2. Whether the payment of just compensation of DAR to HLI hinders the distribution of the

lands to the FWBs?

HELD:

1. The home lots already received by the FWBs shall be respected with no obligation to

refund or to return them. However, since the SDOA is revoked, the Court ordered DAR

to pay HLI just compensation as per the Constitution, that the taking of lands for agrarian

reform must be made through payment of just compensation.

2. With the nullification of the SDOA, lands should be immediately and without delay be

distributed to the farmworker beneficiaries. Hence, the remand of the determination of

the just compensation due to petitioner HLI should not in any way hinder the immediate

distribution of the farmlands in Hacienda Luisita. Legal processes regarding the

determination of the amount to be awarded to the corporate landowner in case of non-

acceptance, must not be used to deny the farmworker beneficiaries the legal victory they

have long fought for and successfully obtained.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Motion To Lift Bench WarrantDocument3 pagesMotion To Lift Bench WarrantRaffyLaguesma67% (3)

- Motion To Lift Bench WarrantDocument3 pagesMotion To Lift Bench WarrantRaffyLaguesma67% (3)

- Motion To Lift Bench WarrantDocument3 pagesMotion To Lift Bench WarrantRaffyLaguesma67% (3)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Post Judgment RemediesDocument9 pagesPost Judgment RemediesRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Circular No. 371 - Revised Guidelines On The Pag-IBIG Group Housing Loan ProgramDocument15 pagesCircular No. 371 - Revised Guidelines On The Pag-IBIG Group Housing Loan ProgramRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Code of Professional ResponsibilityDocument9 pagesCode of Professional ResponsibilitybbysheNo ratings yet

- 209 - Suggested Answers in Civil Law Bar Exams (1990-2006)Document124 pages209 - Suggested Answers in Civil Law Bar Exams (1990-2006)ben_ten_1389% (19)

- Cadastral Proceedings Require Proper NoticeDocument1 pageCadastral Proceedings Require Proper NoticeRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- DANON v. BRIMODocument1 pageDANON v. BRIMOk santos50% (2)

- Solving Construction Problems Step-by-StepDocument6 pagesSolving Construction Problems Step-by-StepAlexNo ratings yet

- Goodland Company vs. Asia United Bank REM DisputeDocument2 pagesGoodland Company vs. Asia United Bank REM DisputeRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Managerial EconomicsDocument6 pagesManagerial EconomicsAhmad Hirzi Azni100% (1)

- Hilton Pharma Report on Pharmaceutical IndustryDocument8 pagesHilton Pharma Report on Pharmaceutical IndustryFakhrunnisa khanNo ratings yet

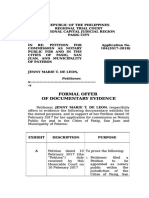

- Formal Offer of Evidence Notarial Commission JTDDocument7 pagesFormal Offer of Evidence Notarial Commission JTDRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Celtic Pattern Brushes by JerrydmillsDocument1 pageCeltic Pattern Brushes by JerrydmillsRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- (ENBANC) POLITICAL - Cagas Vs COMELEC - No Certiorari For Interlocutory Order But Petition For ReviewDocument16 pages(ENBANC) POLITICAL - Cagas Vs COMELEC - No Certiorari For Interlocutory Order But Petition For Reviewjstin_jstinNo ratings yet

- Freedom of Information (E.O. No. 2, S.2016)Document5 pagesFreedom of Information (E.O. No. 2, S.2016)RaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Whaley Chap 3 HIDC PDFDocument76 pagesWhaley Chap 3 HIDC PDFRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Written Communication SkillsDocument1 pageWritten Communication SkillsRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Atty Manalang-Demigillo Vs TIDCORP - Reorganization of GOCC Is ValidDocument19 pagesAtty Manalang-Demigillo Vs TIDCORP - Reorganization of GOCC Is ValidRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- SC's Significant Decisions 2013-2015Document54 pagesSC's Significant Decisions 2013-2015Fritz MaandigNo ratings yet

- Canlas vs. Chan Lin Po, 2 SCRA 973, July 31, 1961Document8 pagesCanlas vs. Chan Lin Po, 2 SCRA 973, July 31, 1961RaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- J.K. Mercado & Sons vs. Atty. de VeraDocument13 pagesJ.K. Mercado & Sons vs. Atty. de VeraRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Gross IncomeDocument4 pagesGross IncomeRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- In Re Plagiarism Case Against Justice Del CastilloDocument112 pagesIn Re Plagiarism Case Against Justice Del CastilloRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Castilex Industrial Corporation vs. Vasquez, JR., 321 SCRA 393, December 21, 1999Document17 pagesCastilex Industrial Corporation vs. Vasquez, JR., 321 SCRA 393, December 21, 1999RaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Divorce Case Remanded for Hearing on Petitioner's CitizenshipDocument61 pagesDivorce Case Remanded for Hearing on Petitioner's CitizenshipRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Calalas vs. Court of Appeals, 332 SCRA 356, May 31, 2000Document6 pagesCalalas vs. Court of Appeals, 332 SCRA 356, May 31, 2000RaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Batangas Laguna Tayabas Bus Co. vs. IAC, 167 SCRA 379, November 14, 1988Document8 pagesBatangas Laguna Tayabas Bus Co. vs. IAC, 167 SCRA 379, November 14, 1988RaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- II. Public Documents As Evidence and Proof of Notarial Documents Section 23Document2 pagesII. Public Documents As Evidence and Proof of Notarial Documents Section 23RaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Fabre, Jr. vs. Court of Appeals, 259 SCRA 426, July 26, 1996Document8 pagesFabre, Jr. vs. Court of Appeals, 259 SCRA 426, July 26, 1996RaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Andamo vs. Intermediate Appellate Court, 191 SCRA 195, November 06, 1990Document6 pagesAndamo vs. Intermediate Appellate Court, 191 SCRA 195, November 06, 1990RaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- CASES 1 To 5 Conflic of LawsDocument8 pagesCASES 1 To 5 Conflic of LawsEstudyante SalesNo ratings yet

- Case TaxDocument2 pagesCase TaxJhailey Delima VillacuraNo ratings yet

- WSK M2P152 A1a2a3a4Document4 pagesWSK M2P152 A1a2a3a4aldairlopesNo ratings yet

- Purchase Order: Your Company PO#Document4 pagesPurchase Order: Your Company PO#Mera Bharath MahanNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Sales Promotion PDFDocument6 pagesThesis On Sales Promotion PDFchristinajohnsonanchorage100% (2)

- Chicago Meeting Planner PDFDocument216 pagesChicago Meeting Planner PDFphamianickNo ratings yet

- Ihrm 3Document22 pagesIhrm 3Ramish TanvirNo ratings yet

- Labour Management Resource Management DSDocument1 pageLabour Management Resource Management DSHamsa BNo ratings yet

- The Use of Cost Information in Pricing Decisions: Empirical Evidence on How Capacity Utilization and Demand Stochasticity Affect Cost-Price AssociationDocument55 pagesThe Use of Cost Information in Pricing Decisions: Empirical Evidence on How Capacity Utilization and Demand Stochasticity Affect Cost-Price AssociationMULU TEMESGENNo ratings yet

- Understanding the Cradle-to-Grave Carbon Footprint of Structural Precast ConcreteDocument4 pagesUnderstanding the Cradle-to-Grave Carbon Footprint of Structural Precast ConcretetdrnkNo ratings yet

- Shubhashree BansodeDocument68 pagesShubhashree BansodeTasmay EnterprisesNo ratings yet

- SEEMSAN Product RangeDocument12 pagesSEEMSAN Product RangeSPE PROCESS PUMPSNo ratings yet

- 5 Undiscovered Equity Funds With High Growth Potential June 2020 PDFDocument34 pages5 Undiscovered Equity Funds With High Growth Potential June 2020 PDFKOUSHIKNo ratings yet

- Orchid ExportDocument24 pagesOrchid ExportShaz AfwanNo ratings yet

- BB BoxesDocument4 pagesBB BoxesleilycarreyNo ratings yet

- Acctg Lab 5.Document4 pagesAcctg Lab 5.AngieNo ratings yet

- A Study of Customer Relationship Management Practices in Hoteling SectorDocument9 pagesA Study of Customer Relationship Management Practices in Hoteling SectorkumardattNo ratings yet

- The Analysis of Financial Reports Automobile Assembler Industry in PakistanDocument55 pagesThe Analysis of Financial Reports Automobile Assembler Industry in PakistanMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Tariff Commission FunctionsDocument12 pagesTariff Commission FunctionsShane EstNo ratings yet

- ElementsBookKeepingAccountancy SQPDocument6 pagesElementsBookKeepingAccountancy SQPMohd JamaluddinNo ratings yet

- VIT - Total Quality Management - 6Document16 pagesVIT - Total Quality Management - 6Manasi PatilNo ratings yet

- S14 Hydraulic TankDocument16 pagesS14 Hydraulic TankFRANCO RODRIGO MAMANI FLORESNo ratings yet

- Reservation Confirmed: Tel: +971 6 558 0000, Fax: +971 6 558 0008Document4 pagesReservation Confirmed: Tel: +971 6 558 0000, Fax: +971 6 558 0008S DevaNo ratings yet

- Cash and Cash Equivalents FundamentalsDocument10 pagesCash and Cash Equivalents FundamentalsGRACE ANN BERGONIONo ratings yet

- RUS Pace and New ERA Program Webinar Details 5-17-2023Document7 pagesRUS Pace and New ERA Program Webinar Details 5-17-2023Linda ReevesNo ratings yet

- Vendors From The SPD e CatalogDocument112 pagesVendors From The SPD e CatalogLuis FelipeNo ratings yet

- Special Power of Attorney GeneralDocument2 pagesSpecial Power of Attorney GeneralOlivia CruzNo ratings yet

- Economics of Managerial Decisions 1st Edition Blair Test BankDocument36 pagesEconomics of Managerial Decisions 1st Edition Blair Test BankCynthiaJordanMDkqyfj100% (19)