Professional Documents

Culture Documents

McKinsey Quarterly: New Tools For Negotiators

Uploaded by

Tera AllasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

McKinsey Quarterly: New Tools For Negotiators

Uploaded by

Tera AllasCopyright:

Available Formats

negotiators

egotiations are the stuff of business life, and volumes of advice

tell managers how to prepare for and conduct them. But most of the

advice applies to deals that are simpler than those pursued today. Negotia-

tions now typically involve many parties that have an interest in the out-

comethe stakeholdersand require decisions on many complex issues.

Immense sums of money may ride on the outcome.

86

Tera Allas and Nikos Georgiades

A few simple ideas make it possible to construct powerful strategies

for even the most complex deals.

N

New tools for

26934(086-097)Q2_Negotiationsv5 6/26/01 9:33 AM Page 86

87

Sophisticated support for negotiators is availablefor example, computer

simulation models based on dynamic game theory. These models can predict

the behavior of stakeholders in multiparty deals and guide negotiators to

winning strategies. As yet, however, few business leaders feel comfortable

surrendering their personal judgment on such crucial issues to a black box.

We have therefore been developing a middle way: a set of readily understood

tools to help decision makers in complex multiparty negotiations.

1

With

the help of these tools, negotiators can develop strategies that are not only

1

The methodology builds on the theoretical and empirical work carried out by Decision Insights Incorporated

(DII), a consulting company specializing in the computer-supported simulation of negotiations and political

decisions. In particular, DIIs dynamic-game-theory model for conducting multiparty negotiations gave us

the concepts of position, salience, and clout, which are fundamental to analyzing the behavior of

stakeholders in negotiations.

TODD DAVIDSON

26934(086-097)Q2_Negotiationsv5 6/26/01 9:33 AM Page 87

favorable to them but also palatable to the other parties. This method rests

on the same logic as sophisticated simulation tools but doesnt require an

elaborate computer model. It has been used so far to develop strategies for

several real-life negotiations and is appropriate whenever many stakeholders

have different goals on a number of issues and the final decision emerges

from bargaining among those stakeholders. The tools are therefore relevant

to mergers and acquisitions, partnerships and alliances, regulatory rulings,

litigation, and labor disputesin

short, to many of the items at the

top of a chief executive officers

agenda.

Applying the tools at the start of

a deal should answer many crucial

questions. Who are a deal makers true allies and enemies? What is the

chance that a particular outcome will stick? Who is worth lobbying for

support on particular issues? What bargaining chips can be traded for that

support? Used together, these fact-based tools suggest effective strategies

for arriving at decisions that all parties can accept, and they help negotiators

refine their plan of action as circumstances change. To see how the tools

operate, consider how they helped negotiators in two real situations.

Power play

A European government decided to liberalize its electricity generation and

supply industry. One major move in carrying out that plan was the privatiza-

tion of a near-monopoly utility, which we will call Power. Negotiations had

to be conducted on several issues, including the level of end-customer tariffs

that Power could charge, the wholesale-market structure most appropriate

for competition, and the possible forced sale of Powers generating plants.

Powers first task was to identify the key issues and the range of possible

outcomes for each. On the tariff issue, for example, the regulator proposed

a one-off cut of 15 percent in tariffs charged to end customers. Power, by

contrast, aimed to keep the existing tariff levels. In addition to such obvious

issues, Power considered several others, such as green subsidies: higher

tariffs for electricity produced at environmentally friendly plants. Some of

the additional issues at first seemed immaterial but later turned out to be

important.

Next, Power had to identify all of the stakeholders that might inuence the

decision on any issue and to understand the objectives of each. It identified

a total of 16 parties, including the regulator, the Ministry of Industry, the

88 THE McKI NSEY QUARTERLY 2001 NUMBER 2

Who are a deal makers allies and

enemies? What is the chance that

a particular outcome will stick?

26934(086-097)Q2_Negotiationsv5 6/26/01 9:33 AM Page 88

Treasury, labor unions, competitors, the free-market system operator, and

Power itself. Although the number of parties was large, a negotiator using

our tools requires only three pieces of information about stakeholders to

predict their behavior on any issue.

1. Position: What is the stakeholders preferred outcome on the issue? Is the

stakeholder arguing for one of the extremes on the range of possible

outcomes, for example? For a stakeholder who hasnt stated a position

on a particular issue, what would the rational position be?

2. Salience: How important is this issue to the stakeholder as compared with

all other issues? For example, would the stakeholder drop everything else

to attend a meeting on this issue? What do we know about this persons

past interest in the issuefor instance, his or her willingness to spend

resources on it?

3. Clout: As compared with other players, how much power does the stake-

holder have to inuence the decision on this issue? In the case of Powers

future tariffs, for example, the regulator had the highest clout, followed

by Power and the Treasury.

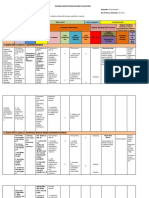

It is helpful to express

this information by

assigning a number

from 0 to 100 to repre-

sent each stakeholders

position. On tariffs,

Power chose 0 to repre-

sent its own position

and 100 for the regula-

tors. The other stake-

holders fell somewhere

between these two

extremes (Exhibit 1).

As for salience, a rating

of 100 means that this

is the most important

issue for the stake-

holder, a rating of 50

that it is one of several

important issues but

not the most important,

and a rating of 0 that it

89 NE W T OOL S F OR NE GOT I AT ORS

E X H I B I T 1

The stage is set

Summary of each stakeholders stance on the end-user tariffs issue based on a scale

of 0 to 100

1

1

For position, 0 = Powers position and 100 = regulators position; for salience, 0 = unimportant and

100 = most important; for clout, 0 = no power to influence and 100 = most powerful influencer.

2

Position is stakeholders preferred outcome on particular issue; salience is issues level of

importance to stakeholder; clout is extent of stakeholders power to influence decision on issue.

Issue: Green subsidies

Issue: Forced divestitures

Issue: Wholesale-market structure

Issue: End-user tariffs

Position

S

t

a

k

e

h

o

l

d

e

r

s

Salience Clout

Labor unions 0 20 20

Treasury 0 40 60

Ministry of Industry 30 35 50

Regulator 100 85 100

Power 0 90 70

System operator 0 30 50

Competitors 50 50 20

Key characteristics

2

26934(086-097)Q2_Negotiationsv5 6/26/01 9:33 AM Page 89

is unimportant. To express clout, the stakeholder with the greatest inuence

on an issuein the case of tariffs, the regulatorwould get a rating of 100;

the others would get fewer points.

The task of gathering all of this information may seem daunting. In our

experience, however, it is possible to find people who can provide answers

based on their dealings with the stakeholders and their knowledge of the

current negotiations.

If so, a day or two

will suffice to question

these people carefully,

preferably in a work-

shop setting; to cali-

brate their inputs; and

to arrive at consensus

estimates. Recording

the results in an elec-

tronic format will be

useful for later analysis.

The first cut

Having undertaken

this preparatory work,

Power was ready to see

how the negotiations

might pan out on each

issue. The first tool,

called an outcome

continuum, graphs each

stakeholders position

on a given issue relative

to the two extremes. By

weighting the players

positions according to

salience and clout and

then calculating the

average, you can foretell

the result of a pure compromise vote, with no bargaining among the

parties. This analysis quickly showed Power that it faced tough opposition

on the tariff issue, with a potential outcome far from its ideal (Exhibit 2,

part 1).

90 THE McKI NSEY QUARTERLY 2001 NUMBER 2

E X H I B I T 2

Tariff trouble

1

Product of salience and clout.

Tool 1: Outcome continuum for end-user tariffs issue

By graphing the expected weighted average outcome of a pure

compromise vote with no bargaining among the stakeholders . . .

1

. . . Power realized that a straightforward

compromise would prove impossible

Tool 2: Stability analysis for end-user tariffs issue

D

i

s

t

a

n

c

e

f

r

o

m

w

e

i

g

h

t

e

d

a

v

e

r

a

g

e

o

u

t

c

o

m

e

2

100

Maximum

reduction

Ministry of

Industry Competitors Regulator

0

No

reduction Weighted

average = 43

Unhappy

players with

limited power

to influence

the outcome

Players not

likely to care or

to have enough

power to

influence the

outcome

High

Near

Far

Ministry of

Industry

Competitors

Combined Salience and Clout

1

Power

Treasury

System

operator

Labor

unions

Low

Regulator

Players

likely to

challenge

the

outcome

Players

likely to

cement the

outcome

Treasury

System operator

Power

Labor unions

26934(086-097)Q2_Negotiationsv5 6/26/01 9:33 AM Page 90

However, the outcome predicted by a pure vote usually doesnt materialize

in reality. When negotiators dont like what they see coming, they bargain.

To estimate the probability that all of the negotiating parties would accept

the pure-voting outcome, Power applied the second tool, stability analysis,

which examines how far the outcome is from each partys preference, how

much each party cares about winning on the issue, and how important the

parties are in reaching an agreement on it. If too many important players are

dissatisfied with the outcome, it isnt likely to be stable.

In Powers case, stability analysis showed that a straightforward compromise

on the tariff issue would leave Power and the regulator very unhappy; both

were likely to fight on (Exhibit 2, part 2). Power therefore had to apply the

next three tools to find subtle ways of tipping the balance in its favor.

Allies and enemies, influencers and bargaining chips

First, Power used a stakeholder classification, which identifies each stake-

holder as an ally, an enemy, or in-between on every issue (Exhibit 3). This

exercise provides a

useful overview of the

main challenges and

opportunities in the

negotiations as a whole;

it showed, for example,

that Power and the

regulator were enemies

pretty much across the

board. Power also

found that on the issue

of the wholesale-market

structure, it could hope

to get its way fairly

easily, since none of

the stakeholders were

outright enemies.

To see which of the potential allies would make the most useful friends,

Power placed the stakeholders on a negotiation landscape for each issue.

Players with a lot at stake but little inuence are followersgood to have

on your side but not, given their lack of clout, worth much effort to win.

The shapers, by contrast, both care about the issue and can inuence the

outcome, so they are natural partnersor very strong enemies. Just as

91 NE W T OOL S F OR NE GOT I AT ORS

E X H I B I T 3

Friend or foe?

End-user

tariffs

Wholesale-

market

structure

Forced

divestitures

Green

subsidies

S

t

a

k

e

h

o

l

d

e

r

s

Issues

Ally In-between Enemy

Tool 3: Stakeholder classification (from Powers perspective)

System operator

Competitors

Labor unions

Treasury

Ministry of Industry

Regulator

26934(086-097)Q2_Negotiationsv5 6/26/01 9:33 AM Page 91

important are the

inuencers, who are

not greatly concerned

with the issue but have

a good deal of inuence

over it. If you can

persuade them to

support your position,

you are much more

likely to win.

In Powers case, the

shapers on the tariff

issue were Power itself

and the regulator, an

enemy. But there were

several inuencers

including the Treasury,

the Ministry of

Industry, and the

system operatorthat

Power could court

(Exhibit 4). It now

realized that it had to

convince them that the

tariff issue was salient

for them as well.

In some cases, lobbying

alone can work, but

certain stakeholders

want something

in return for their

support. Moreover,

Power still needed to

get additional leverage

with the most problematic stakeholder, the regulator. Power discovered its

best bargaining chips by identifying the issues for which it was itself an

inuencer. To find them, Power plotted the salience of every issue for itself

and for each other stakeholder on separate relationship analysis matrices.

The upper-left-hand quadrant contains the negotiators bargaining chips:

issues that he or she is willing to compromise on but that are important to

92 THE McKI NSEY QUARTERLY 2001 NUMBER 2

E X H I B I T 4

Friends in unlikely places: Influencers can tip the balance

Ally In-between Enemy

S

a

l

i

e

n

c

e

Low High

Low

High

Clout

Treasury

Regulator

Shapers:

Craft joint

strategy with

strong allies

Influencers:

Lobby to

increase

salience and

gain support

Followers:

Bring into

coalition if

little effort

required

Bystanders:

Ignore

Tool 4: Negotiation landscape for end-user tariffs issue

Labor

unions

Power

System operator

Ministry of Industry

Competitors

E X H I B I T 5

Green subsidies: Powers leverage

R

e

g

u

l

a

t

o

r

s

s

a

l

i

e

n

c

e

Low High

Low

High

Deal breakers:

Negotiate

through

bargaining,

lobbying, and

disaggregating

1

Easy wins:

Capture

immediately

or delay for

tactical

reasons

Bargaining

chips:

Exchange for

concessions on

other issues

Uninteresting:

Ignore

Powers salience

End-user tariffs

Green subsidies

Wholesale-market

structure

Forced divestitures

Tool 5: Relationship analysis (Power versus regulator)

1

Solutions for deal-breaking issues can often be found by dividing issues into subcomponentsfor

instance, end-user tariffs issue could be viewed as 3 subissues: initial tariff reduction, target levels

in 5 years, and rate of ongoing reductions.

Regulators position relative to Power

Ally In-between Enemy

26934(086-097)Q2_Negotiationsv5 6/26/01 9:33 AM Page 92

the other party.

2

It turned out that on the issue of green subsidies, which

Power had initially regarded as insignificant, it could give a good deal of

ground to the regulator in return for a more favorable outcome on tariffs

(Exhibit 5).

By working through these five analyses, Power discovered early on that it

had little chance of winning on the tariff issue without hard bargaining.

But it also found strong bargaining

tactics. To build an alliance against

the regulators tough stand, Power

could try to increase the salience of

the tariff issue for the Treasury and

other stakeholders, which already

favored Powers position but would

have to be persuaded to support it

more actively. Power could also bargain away green subsidies in return for

higher tariffs. Although these strategies were counterintuitive, they were

practical and in marked contrast to Powers initial confusion in the face of

so many issues and stakeholders.

Adding dynamics

These analyses can give you an exact snapshot of your own and your oppo-

nents negotiating strengths, along with insights into ways of changing the

dynamics of the game. Negotiators will have more confidence in their

chosen strategy if they can see what happens when they apply it to the next

round of negotiationssomething they can do by rerunning the first two

analyses with updated information and then tracking the results on a

spreadsheet.

A conglomerate we will call Alpha used this technique in negotiations

concerning Coolstuff, a high-technology company in which Alpha and

another conglomerate, Beta, each had a 50 percent stake (Exhibit 6, on the

next page). The two conglomerates had set up Coolstuff to share R&D costs

and expertise, and the venture had successfully commercialized many of its

inventions. In contrast, Gamma, an independent start-up in the same field,

was brilliant at developing technology but less successful in the marketplace.

The management teams of Gamma and Coolstuff wanted the two companies

to join forces so that they could apply Coolstuffs marketing know-how to

93 NE W T OOL S F OR NE GOT I AT ORS

2

To find bargaining chips even more precisely, a negotiator could also take into account its relative clout

on each issue. The greater its clout, the more valuable the bargaining chip.

To build an alliance against the

regulators tough stand, Power

could try to increase the salience

of the tariff issue for the Treasury

26934(086-097)Q2_Negotiationsv5 6/26/01 9:33 AM Page 93

Gammas unique technologies. For Coolstuff, the price of the deal would

depend on the relative valuation of the two companies and whether the

deal was structured as an acquisition of Gammawith a corresponding

premiumor as a merger. An acquisition would also raise the issue of

whether Coolstuff would pay in cash or in shares.

Irreconcilable differences?

Despite the commercial logic of a deal, differences in the expectations of

the companies owners seemed likely to make it impossible to consummate.

Alpha hoped that Beta would in due course buy out its Coolstuff stake.

Since Alphas share of the combined Coolstuff-Gamma entity would be

more valuable than the companys share of Coolstuff alone, Alpha naturally

wanted a highly valued Coolstuff to merge with a relatively low-valued

Gamma for the lowest possible outlay of cash.

94 THE McKI NSEY QUARTERLY 2001 NUMBER 2

P

o

s

i

t

i

o

n

o

n

i

s

s

u

e

s

r

e

g

a

r

d

i

n

g

C

o

o

l

s

t

u

f

f

E X H I B I T 6

The players

Acquisition Merger Merger

Payment to

Gamma in

cash or shares?

Cash Shares Shares

Brand name? Coolstuff Coolstuff

Coolstuff-

Gamma

Merger or

acquisition

(with premium)?

High High Low

Valuation of

Coolstuff relative

to Gamma?

S

a

l

i

e

n

c

e

o

n

i

s

s

u

e

s

r

e

g

a

r

d

i

n

g

C

o

o

l

s

t

u

f

f

High-tech company with successful track record

of commercializing new inventions

Wants to merge with Gamma to benefit from its

R&D leadership

Coolstuff

Gamma Beta Alpha

N

e

g

o

t

i

a

t

o

r

s

Conglomerate;

50% owner of

Coolstuff

Wants to reshape

corporate portfolio

and sell stake in

Coolstuff to Beta

for good price

Conglomerate;

50% owner of

Coolstuff

Wants long-term

control over

Coolstuff and

Gamma

Wants to retain

Coolstuff brand

Independent start-up

with strong R&D track

record

Wants to merge with

Coolstuff to benefit

from its marketing

leadership

Wants to retain some

management control

and to share in

potential economic

benefits of the merged

company

Very

low

Very

high

Very

low

Very

high

Very

low

Very

high

Very

low

Very

high

26934(086-097)Q2_Negotiationsv5 6/26/01 9:33 AM Page 94

Beta was in the business for the long haul, so it sought full management

control of Gamma, with or without Alpha. Beta therefore wanted Coolstuff

to hold all of the equity in the new company, leaving Gammas original

owners with none. Rather than merge, Beta wanted Coolstuff to acquire

Gammaa course that would make it easier to replace Gammas manage-

ment. Although the price might include an acquisition premium, Beta cared

more about control and the long-term potential of the business. Beta was

also determined to preserve the Coolstuff brand as the public face of the

new company.

The owner-managers of Gamma wanted it to be valued

as highly as possible. They also wanted shares in the new

venture as payment so they could benefit from the future

commercial success of the technologies they had so passion-

ately developed. They envisioned the new company as a

merger of equals, branded Coolstuff-Gamma.

The search for common ground

Alpha ran the outcome continuum analysis, with dispiriting results. Beta,

as the negotiator with the most clout and salience, would probably wish

to acquire Gamma for cash and to keep the Coolstuff brand name. Stability

analysis suggested that although Alpha might accept this arrangement,

Gamma would be so dissatisfied that the deal would never be consum-

mated, and Alpha would have no chance to get out of its unwanted invest-

ment in Coolstuff. Still, the game wasnt lost: every stakeholder attached a

different degree of importance to each issue, so there might be room for

bargaining.

The stakeholder classification reminded Alpha that Beta and Gamma might

collaborate with Alpha on some issues even if those companies were enemies

on others. Gamma was Alphas natural ally on the merger-versus-acquisition

issue, for example, while Beta would support Alphas preference for a high

relative valuation of Coolstuff. The negotiation landscape analysis on each

of the issues showed Alpha which party it should lobby for support on the

questions it cared about most. Alpha had a better chance of getting its way

on the valuation, for instance, if it could increase the issues salience to Beta.

It could also try to get Gamma to push harder for a merger rather than an

acquisition. Both companies were predisposed to support Alpha on these

issues, but it had to persuade them to use their clout.

A relationship analysis showed Alpha what it might offer in exchange. The

terms of payment and the name of the future brand emerged as powerful

95 NE W T OOL S F OR NE GOT I AT ORS

26934(086-097)Q2_Negotiationsv5 6/26/01 9:33 AM Page 95

bargaining chips for dealings with Gamma. Alpha could promise to wield

more of its own clout to support the desire of Gammas owners to retain

stock in the new company if Gamma in return accepted a relatively high

valuation for Coolstuff. Alpha could also agree to rebrand the new

companyan issue much more

important to Gammas management

than to Alphas.

But the same analysis vis--vis Beta

produced rather problematic results.

Apparently, one of the most effective

ways of persuading it to accept a

merger would be for Alpha to grant the company a cash-based deal. Alpha

could also help Beta get its way on the brand issue. Which party should

Alpha support on which of these issues? What would be the most effective

use of Alphas bargaining chips?

And the winner is . . . everyone

To find out, Alpha ran the stability analysis again, testing which of two

strategies was more likely to yield a deal among the parties. Should Alpha

back Gammas desire for a combined brand name but persuade Gamma to

accept a cash deal? Or should it support Beta on maintaining the current

brand but push for a share-based deal more acceptable to Gamma? Rerun-

ning the analysis showed that the latter strategy was the only way to make

everyone happy enough to agree to a deal; the other route would still leave

Gamma highly dissatisfied. In contrast, securing payment in shares would

be just enough to persuade Gamma to go ahead with the deal and pave the

way for Alphas exit from the Coolstuff venture.

Alpha needed only two days to gather and structure the information for

these analyses and about half a day to apply them, with iterations. The effort

yielded a practical strategy for resolving what had seemed to be a total

impasse. The deal went ahead.

More advanced game theory modeling can includeat a fairly low cost an

almost infinite number of dynamic simulations, which allow a negotiator to

identify and test strategies with greater precision. So far, few businesses use

this approach. Managers seem reluctant to apply mathematics to a process

inherently concerned with human judgment.

96 THE McKI NSEY QUARTERLY 2001 NUMBER 2

Alpha needed only two days to

gather and structure the data

needed for these analyses and

only half a day to apply them

26934(086-097)Q2_Negotiationsv5 6/26/01 9:33 AM Page 96

But past negotiations reveal that stakeholders behave predictably given their

position, salience, and clout on each issue. Negotiations are therefore suscep-

tible to more rigorous analysis than traditional approaches allow. Five simple

toolsthe outcome continuum, the stability analysis, the stakeholder classi-

fication, the negotiation landscape, and the relationship analysiscan give

negotiators the best of both worlds.

Tera Allas is an associate principal and Nikos Georgiades is a consultant in McKinseys London

office. Copyright 2001 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved.

97 NE W T OOL S F OR NE GOT I AT ORS

26934(086-097)Q2_Negotiationsv5 6/26/01 9:33 AM Page 97

You might also like

- PWC Wealth Management Firm Emerging Market GrowthDocument31 pagesPWC Wealth Management Firm Emerging Market GrowthMartin JpNo ratings yet

- Roland Berger European Private Equity Outlook 2013 20130421Document30 pagesRoland Berger European Private Equity Outlook 2013 20130421Katrina HamptonNo ratings yet

- Deloitte & DNV GL Seafood TradeDocument24 pagesDeloitte & DNV GL Seafood TradeweNo ratings yet

- BPV Organisational EnablersDocument10 pagesBPV Organisational EnablersfwfsdNo ratings yet

- AT Kearney Energy Transition Institute Media Presentation180606aDocument9 pagesAT Kearney Energy Transition Institute Media Presentation180606aAyesha Khan JamilNo ratings yet

- WEF Alternative Investments 2020 FutureDocument59 pagesWEF Alternative Investments 2020 FutureOwenNo ratings yet

- Climate Change and The Role of The Chemical IndustryDocument23 pagesClimate Change and The Role of The Chemical IndustryfwfsdNo ratings yet

- McKinsey InovaçãoDocument28 pagesMcKinsey InovaçãoVasco Duarte BarbosaNo ratings yet

- BPV ApproachDocument13 pagesBPV ApproachfwfsdNo ratings yet

- CGD Is Opportunity Real Anshuman Maheshwary AtkearneyDocument12 pagesCGD Is Opportunity Real Anshuman Maheshwary AtkearneyayushiNo ratings yet

- ZF Telco Conference v1Document30 pagesZF Telco Conference v1imatacheNo ratings yet

- Shaping The Future of Production: A.T. Kearney Collaboration With The World Economic Forum (WEF)Document35 pagesShaping The Future of Production: A.T. Kearney Collaboration With The World Economic Forum (WEF)karol torres100% (1)

- Product Refresher Training For Mass Market RM: Online Training Document February 2017Document36 pagesProduct Refresher Training For Mass Market RM: Online Training Document February 2017AsadNo ratings yet

- Wenban MonitorDocument21 pagesWenban Monitoralex.nogueira396No ratings yet

- Library of Common SlidesDocument197 pagesLibrary of Common SlidesJoseph MoutranNo ratings yet

- EY Parthenon Pharma Industry Changes Survey Final Web 052017 PDFDocument16 pagesEY Parthenon Pharma Industry Changes Survey Final Web 052017 PDFMuhammad HassanNo ratings yet

- PWC Outlook2017 ReportDocument44 pagesPWC Outlook2017 ReportAshishKumarMishraNo ratings yet

- Accountability ManagementDocument18 pagesAccountability ManagementFery Permadi100% (1)

- BCG ConsumatoreDocument37 pagesBCG ConsumatoreAdriano ManiscalcoNo ratings yet

- Quantum Technology MonitorDocument53 pagesQuantum Technology MonitorLuciana ZolaNo ratings yet

- ECO222 Lect Week9 2020 UDocument39 pagesECO222 Lect Week9 2020 UKarina SNo ratings yet

- Charla12AGO2022 TelcoTRENDS Mckinsey 2023-2026CEDocument29 pagesCharla12AGO2022 TelcoTRENDS Mckinsey 2023-2026CEalejandro claroNo ratings yet

- Slido OPDocument6 pagesSlido OPshivangi guptaNo ratings yet

- BCG Perspectives - Mobile Payments in Africa: Graphics For ArticleDocument13 pagesBCG Perspectives - Mobile Payments in Africa: Graphics For ArticleJean ClavelNo ratings yet

- Changing Landscape in Container Shipping and The Implications To ShippersDocument51 pagesChanging Landscape in Container Shipping and The Implications To ShipperseyaoNo ratings yet

- MBI Presentation - Chandershekher JoshiDocument8 pagesMBI Presentation - Chandershekher JoshiChander ShekherNo ratings yet

- Deloitte ES Financial Advisory The Logistic HandbookDocument16 pagesDeloitte ES Financial Advisory The Logistic HandbookNavin JollyNo ratings yet

- Roland Berger Li Ion Batteries Bubble Bursts 20121019Document16 pagesRoland Berger Li Ion Batteries Bubble Bursts 20121019ashoho1No ratings yet

- Innovation MckinseyDocument23 pagesInnovation MckinseyVasco Duarte BarbosaNo ratings yet

- 1415 1 RolandBerger ApresentacaoDocument40 pages1415 1 RolandBerger ApresentacaovishansNo ratings yet

- British Tourist Authority Price Sensitivity of Tourism To BritainDocument132 pagesBritish Tourist Authority Price Sensitivity of Tourism To BritainLaura AndreeaNo ratings yet

- AtKearney - A Viable Future Model For The InternetDocument57 pagesAtKearney - A Viable Future Model For The InternetGiovanni GangemiNo ratings yet

- Indonesia e Conomy Sea 2021 ReportDocument17 pagesIndonesia e Conomy Sea 2021 ReportEep Saefulloh FatahNo ratings yet

- India's Automotive Industry: Necessary Steps On Our Way To Global ExcellenceDocument53 pagesIndia's Automotive Industry: Necessary Steps On Our Way To Global Excellencevaragg24No ratings yet

- 2017-11 AID Milan Fintech, How Financial Institutions McKinsey PDFDocument21 pages2017-11 AID Milan Fintech, How Financial Institutions McKinsey PDFHieu Nguyen MinhNo ratings yet

- Task 9 Agency Status and Plans: Analysis DocumentDocument31 pagesTask 9 Agency Status and Plans: Analysis DocumentManendra Singh KushwahaNo ratings yet

- Mobile Device Market Trends and VendorsDocument49 pagesMobile Device Market Trends and Vendorsasthapriyamvada100% (1)

- Do M&a Create ValueDocument12 pagesDo M&a Create ValueMilagrosNo ratings yet

- Could E-Commerce Disintermediate Supermarkets?: Winning Strategies For CPG CompaniesDocument41 pagesCould E-Commerce Disintermediate Supermarkets?: Winning Strategies For CPG CompanieskrrajanNo ratings yet

- Ism 23Document11 pagesIsm 23ukalNo ratings yet

- 01 - Top 15 PPT Ninja TricksDocument24 pages01 - Top 15 PPT Ninja TricksSANJITNo ratings yet

- Slide Templates: CEO-level Presentation Skills Course: Illustrative Slide Template CollectionDocument22 pagesSlide Templates: CEO-level Presentation Skills Course: Illustrative Slide Template CollectionVenketeshNo ratings yet

- MA Transaction Services TombstonesDocument101 pagesMA Transaction Services TombstonesvramalhoNo ratings yet

- 04 - Convert Symbols To Editable ShapesDocument6 pages04 - Convert Symbols To Editable ShapesSANJITNo ratings yet

- Tdb65pt2 Item5 Presentation LKrstic enDocument23 pagesTdb65pt2 Item5 Presentation LKrstic enBagus EfendiNo ratings yet

- MTA Transformation Plan - Preliminary ReportDocument19 pagesMTA Transformation Plan - Preliminary ReportNewsday100% (1)

- Armenia 2020Document104 pagesArmenia 2020GUINo ratings yet

- BPO in Chile - 2007Document29 pagesBPO in Chile - 2007bgngggggNo ratings yet

- Session 3 - Jan Mischke PDFDocument18 pagesSession 3 - Jan Mischke PDFViet Linh VuNo ratings yet

- Capabilities-Driven Strategy: IMI Kolkata 22nd February 2012 Rudra ChatterjeeDocument25 pagesCapabilities-Driven Strategy: IMI Kolkata 22nd February 2012 Rudra ChatterjeetoabhishekpalNo ratings yet

- Deliverable Completion ReportDocument4 pagesDeliverable Completion ReportJasim's BhaignaNo ratings yet

- M&a Masterclass Presentation SlidesDocument52 pagesM&a Masterclass Presentation SlidesnebonlineNo ratings yet

- Bain CapitalDocument11 pagesBain CapitalRaf SanchezNo ratings yet

- Roland Berger TAB The Winners 20140709Document24 pagesRoland Berger TAB The Winners 20140709Anuj PandeyNo ratings yet

- Go To Asia Strategy: CAGR of 9% 2007-2011 Expected To Reach CAGR of 6.6% Over The 2013-18 PeriodDocument3 pagesGo To Asia Strategy: CAGR of 9% 2007-2011 Expected To Reach CAGR of 6.6% Over The 2013-18 PeriodVignesh GowrishankarNo ratings yet

- Everyday Life and Activities Are Resuming in China: Confirmed New Cases Per Day (Thousands)Document10 pagesEveryday Life and Activities Are Resuming in China: Confirmed New Cases Per Day (Thousands)Pankaj MehraNo ratings yet

- BCG Reigniting Radical Growth June 2019 Tcm9 222638Document33 pagesBCG Reigniting Radical Growth June 2019 Tcm9 222638sdadaaNo ratings yet

- Roland Berger The Second National Tourism Development Plan 2017 2021Document112 pagesRoland Berger The Second National Tourism Development Plan 2017 2021suzNo ratings yet

- Operations Due Diligence: An M&A Guide for Investors and BusinessFrom EverandOperations Due Diligence: An M&A Guide for Investors and BusinessNo ratings yet

- UK University Graduate Earnings Outcomes by Subject Provider Gender 5 Years After GraduationDocument2 pagesUK University Graduate Earnings Outcomes by Subject Provider Gender 5 Years After GraduationTera Allas100% (1)

- Delivering Productivity and Good Jobs: Why Industrial Strategy Must Focus On Fuman CapitalDocument14 pagesDelivering Productivity and Good Jobs: Why Industrial Strategy Must Focus On Fuman CapitalTera Allas100% (1)

- Public Sector As A Driver of Innovation: Practitioner Insights On Getting It RightDocument10 pagesPublic Sector As A Driver of Innovation: Practitioner Insights On Getting It RightTera AllasNo ratings yet

- Mind The Gap: Theory and Practice of Economic Policy MakingDocument4 pagesMind The Gap: Theory and Practice of Economic Policy MakingTera AllasNo ratings yet

- HealthInsuranceCertificate-Group CPGDHAB303500662021Document2 pagesHealthInsuranceCertificate-Group CPGDHAB303500662021Ruban JebaduraiNo ratings yet

- Dialog Suntel MergerDocument8 pagesDialog Suntel MergerPrasad DilrukshanaNo ratings yet

- Wind Energy in MalaysiaDocument17 pagesWind Energy in MalaysiaJia Le ChowNo ratings yet

- Hotel ManagementDocument34 pagesHotel ManagementGurlagan Sher GillNo ratings yet

- How To Create A Powerful Brand Identity (A Step-by-Step Guide) PDFDocument35 pagesHow To Create A Powerful Brand Identity (A Step-by-Step Guide) PDFCaroline NobreNo ratings yet

- MRT Mrte MRTFDocument24 pagesMRT Mrte MRTFJonathan MoraNo ratings yet

- Computer First Term Q1 Fill in The Blanks by Choosing The Correct Options (10x1 10)Document5 pagesComputer First Term Q1 Fill in The Blanks by Choosing The Correct Options (10x1 10)Tanya HemnaniNo ratings yet

- Ces Presentation 08 23 23Document13 pagesCes Presentation 08 23 23api-317062486No ratings yet

- Polytropic Process1Document4 pagesPolytropic Process1Manash SinghaNo ratings yet

- SM Land Vs BCDADocument68 pagesSM Land Vs BCDAelobeniaNo ratings yet

- DesalinationDocument4 pagesDesalinationsivasu1980aNo ratings yet

- Course Specifications: Fire Investigation and Failure Analysis (E901313)Document2 pagesCourse Specifications: Fire Investigation and Failure Analysis (E901313)danateoNo ratings yet

- Ludwig Van Beethoven: Für EliseDocument4 pagesLudwig Van Beethoven: Für Eliseelio torrezNo ratings yet

- Production - The Heart of Organization - TBDDocument14 pagesProduction - The Heart of Organization - TBDSakshi G AwasthiNo ratings yet

- Agfa CR 85-X: Specification Fuji FCR Xg5000 Kodak CR 975Document3 pagesAgfa CR 85-X: Specification Fuji FCR Xg5000 Kodak CR 975Youness Ben TibariNo ratings yet

- 18 - PPAG-100-HD-C-001 - s018 (VBA03C013) - 0 PDFDocument1 page18 - PPAG-100-HD-C-001 - s018 (VBA03C013) - 0 PDFSantiago GarciaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Auditing For Building Construction: Energy and Air Pollution Indices For Building MaterialsDocument8 pagesEnvironmental Auditing For Building Construction: Energy and Air Pollution Indices For Building MaterialsAhmad Zubair Hj YahayaNo ratings yet

- Arduino Based Voice Controlled Robot: Aditya Chaudhry, Manas Batra, Prakhar Gupta, Sahil Lamba, Suyash GuptaDocument3 pagesArduino Based Voice Controlled Robot: Aditya Chaudhry, Manas Batra, Prakhar Gupta, Sahil Lamba, Suyash Guptaabhishek kumarNo ratings yet

- Basics: Define The Task of Having Braking System in A VehicleDocument27 pagesBasics: Define The Task of Having Braking System in A VehiclearupNo ratings yet

- Topic 4: Mental AccountingDocument13 pagesTopic 4: Mental AccountingHimanshi AryaNo ratings yet

- SCDT0315 PDFDocument80 pagesSCDT0315 PDFGCMediaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Motor DrivesDocument24 pagesIntroduction To Motor Drivessukhbat sodnomdorjNo ratings yet

- Tinplate CompanyDocument32 pagesTinplate CompanysnbtccaNo ratings yet

- Final ExamSOMFinal 2016 FinalDocument11 pagesFinal ExamSOMFinal 2016 Finalkhalil alhatabNo ratings yet

- Loading N Unloading of Tanker PDFDocument36 pagesLoading N Unloading of Tanker PDFKirtishbose ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Fidp ResearchDocument3 pagesFidp ResearchIn SanityNo ratings yet

- Discover Mecosta 2011Document40 pagesDiscover Mecosta 2011Pioneer GroupNo ratings yet

- SILABO 29-MT247-Sensors-and-Signal-ConditioningDocument2 pagesSILABO 29-MT247-Sensors-and-Signal-ConditioningDiego CastilloNo ratings yet

- Pindyck TestBank 7eDocument17 pagesPindyck TestBank 7eVictor Firmana100% (5)

- American AccentDocument40 pagesAmerican AccentTimir Naha67% (3)