Professional Documents

Culture Documents

TOPS Article

Uploaded by

syiiraOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

TOPS Article

Uploaded by

syiiraCopyright:

Available Formats

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

This article was downloaded by: [Auburn University]

On: 23 November 2010

Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 917345050]

Publisher Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-

41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Sports Sciences

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713721847

Test of performance strategies: Development and preliminary validation of

a comprehensive measure of athletes' psychological skills

Patrick R. Thomas; Shane M. Murphy; Lew Hardy

To cite this Article Thomas, Patrick R. , Murphy, Shane M. and Hardy, Lew(1999) 'Test of performance strategies:

Development and preliminary validation of a comprehensive measure of athletes' psychological skills', Journal of Sports

Sciences, 17: 9, 697 711

To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/026404199365560

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/026404199365560

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or

systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or

distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents

will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses

should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss,

actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly

or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Jour nal of Sports Sciences, 1999, 17, 697711

Jour nal of Sports Sciences ISSN 0264-0414 print/ISSN 1466-447 X online Taylor & Francis Ltd

Test of performance strategies: Development and

preliminary validation of a comprehensive measure

of athletes psychological skills

PATRICK R. THOMAS,

1

* SHANE M. MURPHY

2

and LEW HARDY

3

1

Centre for Movement Education and Research, GriYth University, Mt. Gravatt Campus, Queensl and 4111,

Australia,

2

Gold Medal Psychological Consultants, 500B Monroe Tur npike, Suite 106, Monroe, CT 06468, USA and

3

School of Sport, Health and Physical Education Sciences, University of Wales, Bangor, Gwynedd LL57 2DG, UK

Accepted 23 March 1999

We report the initial stages of validation of the 64-item Test of Performance Strategies, a self-report instrument

designed to measure the psychological skills and strategies used by athletes in competition and during practice.

Data were obtained from a sample of 472 athletes competing across a range of performance standards in a wide

variety of sports. Exploratory factor analyses of their responses produced eight competition strategy subscales

and eight practice strategy subscales, each consisting of four items. Internal consistencies of the subscales ranged

from 0.66 to 0.81 (x = 0.75). Correlations among strategies were examined within and between performance

contexts. Subgroups deW ned by age, sex and current standard of performance in sport diV ered signiWcantly in

their psychological skills and strategies.

Keywords: assessment, competition, instrument, practice.

Introduction

The assessment of athletes psychological skills is of

both theoretical and applied interest to sport psycholo-

gists; over the last 10 years or so, several psychological

skills inventories have been proposed. The Psycho-

logical Performance Inventory (PPI) was designed to

assess `mental strengths and weaknesses (Loehr, 1986,

p. 157) on a proW le that incorporated seven factors:

self-conW dence, negative energy, attention control,

visual and imagery control, motivational level, positive

energy and attitude control. The PPI was one of the

W rst instruments to include items describing athletes

speciW c psychological behaviours (e.g. `Before com-

petition, I picture myself performing perfectly; `My

muscles become overly tight during competition) and

their self-evaluations (e.g. `I see myself as more of a loser

than a winner in competition; `I am a mentally tough

competitor). The PPI was developed to improve

athletes awareness and understanding of their mental

skills. Although it has been used by consultants as an

* Author to whom all correspondence should be addressed. e-mail:

p.thomas@mailbox.gu.edu.au

assessment tool in applied settings, little research has

been conducted on the validity and reliability of the PPI,

and it has not been widely used as a research tool in

psychological interventions.

The Psychological Skills Inventory for Sport (PSIS;

Mahoney et al., 1987) has probably been the most

popular and useful instrument for the assessment of

psychological skills. In a study of 44 North American

applied sport psychology consultants, Gould et al.

(1989) found that the PSIS was the only psychological

skills assessment instrument mentioned by more than

one respondent, and that it was rated as the most use-

ful test then available to applied consultants (it scored

a mean of 8.8 on a 10-point scale). The PSIS was

developed by Mahoney and co-workers (Mahoney and

Avener, 1977; Shelton and Mahoney, 1978; Mahoney

et al., 1987) in an attempt to assess the psychological

skills relevant to exceptional athletic performance. The

original PSIS consisted of 51 true-or-false items

developed to identify diVerences in the use of psycho-

logical skills by elite, pre-elite and collegiate-standard

athletes. Based on item, discriminant, factor and cluster

analyses of 713 athletes responses, six subscales of

the PSIS were identiW ed. These subscales were: anxiety

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

A

u

b

u

r

n

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

A

t

:

1

8

:

2

6

2

3

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

0

698 Thomas et al.

control, concentration, conW dence, mental preparation,

motivation and team emphasis. Mahoney et al. (1987)

then used the results of these analyses to develop a

revised 45-item version of the PSIS, using a 5-point

Likert type response format. Subsequent research

showed that the PSIS could successfully discriminate

between athletes of varying ability and between the

sexes (Lesser and Murphy, 1988; Greenspan et al.,

1989; White, 1993). However, Mahoney (1989) found

that a sample of non-elite weightlifters scored higher than

a sample of elite weightlifters on W ve of the six subscales.

Other research with the revised PSIS has revealed

several problems, including: very poor internal consist-

ency statistics for W ve of the six subscales proposed

(Chartrand et al., 1992); unreliability of the proposed

factor structure (Tammen and Murphy, 1990); and un-

acceptable goodness-of-W t statistics in a conW rmatory

factor analysis (Chartrand et al., 1992). Further con-

sideration of the item content of the PSIS enables at least

some possible causes of these problems to be identiW ed.

For example, `I often dream about competition loads

negatively on mental preparation; `I try not to think

about my performance during the 24 hours before a

meet loads positively on mental preparation; and `When

I mentally practise my performance I see myself per-

forming just like I was watching a videotape loads

negatively on mental preparation. These W ndings clearly

reXect some considerable diYculties with the PSIS.

A review of more recent assessment instruments

identiW ed only one which appeared to have adequate

psychometric characteristics. The Athletic Coping

Skills Inventory-28 (ACSI-28; Smith et al., 1985) grew

out of the original Athletic Coping Skills Inventory,

which was designed to measure ways in which athletes

cope with the stress of competition (Smith et al., 1990).

The ACSI-28 was designed to assess the psychological

skills that athletes use to manage their sports perform-

ance. It yields a total Personal Coping Resources score,

which is assumed to reXect a multifaceted psychological

skills construct. A principal components analysis of

data from 637 high-school and college athletes on an

87-item instrument yielded eight factors (Smith et al.,

1990). Using 42 items from the original instrument,

Smith et al. (1995) evaluated this eight-factor solution

using conW rmatory factor analysis. The eight-factor

solution was not conW rmed, but when two factors were

combined and a number of items deleted, a revised

seven-factor solution produced a reasonable goodness-

of-W t to the data. The W nal seven factors, using 28

items (the ACSI-28), accounted for slightly more than

50% of the variance in the data. The subscales corres-

ponding to these factors were labelled: coping with

adversity, peaking under pressure, goal-setting/mental

preparation, concentration, freedom from worr y, con-

W dence and achievement motivation, and coachability.

Internal consistency statistics for the seven ACSI-28

subscales ranged from 0.62 (for concentration) to 0.78

(peaking). A sample of 94 intramural and club sport

athletes took the test 1 week apart, and yielded test

retest correlation coeYcients of 0.470.87, although

W ve of the seven subscales had coeYcients over 0.70.

Using the ACSI-28, Smith and Christensen (1995)

examined the relationship between psychological skills,

physical skills and long-term survival in professional

baseball. The results showed that the ACSI-28 was a

useful predictor of which athletes remained active in

professional baseball over a 3-year period. The ACSI-28

was a much better predictor of athletic success for

pitchers than an assessment of physical skill.

The psychometric background of the ACSI-28 seems

stronger than that of previous assessment instruments,

but some cautions apply. The conW rmatory factor

analysis appears to have been conducted on the same

data as the original exploratory principal components

analysis. This violates normal conW rmatory factor

analysis procedures (Schutz and Gessaroli, 1993), so

the proposed factor structure of the ACSI-28 may need

to be interpreted with caution. Moreover, the ACSI-28

does not appear to provide a comprehensive assessment

of psychological skills. The authors acknowledge that

the scale measures `individual diVerences in general

psychological coping resources [as well as] speciW c

psychological skills such as stress management (Smith

et al., 1995, p. 381). Some skills and techniques (e.g.

concentration and goal-setting) are measured, whereas

others (e.g. visualization, self-talk and relaxation) are

not. We would contend that these areas should be

included in a comprehensive measure of sport psycho-

logical skills.

The research reviewed above suggests that a need

remains for a psychometrically sound general measure

of psychological skills that could be used for both

individual assessment purposes and to monitor the

eVects of psychological skills training programmes upon

skill development. In the remainder of this paper, we

describe the development and initial validation of such

an instrument. In developing this instrument, however,

we also wished to address one other issue that appears

largely to have been neglected in the previous literature

on psychological skills assessment; namely, the use of

psychological skills in practice. The psychological skills

training literature invariably emphasizes the importance

of practising psychological skills to gain proW ciency in

their use (see, for example, Vealey, 1988; Hardy et al.,

1996a). Consequently, it is surprising that the research

reviewed has focused exclusively upon the use of

psychological skills in competition, neglecting the use of

psychological skills during training. This is particularly

puzzling because committed athletes spend up to 99%

of their time in training (McCann, 1995). Thus, in

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

A

u

b

u

r

n

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

A

t

:

1

8

:

2

6

2

3

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

0

Test of performance strategies 699

developing a new measure, a decision was made to focus

upon the assessment of psychological skill usage both

during practice and in competition.

Methods

Instr ument development

The development of the Test of Performance Strategies

(TOPS) was based upon the psychological processes

thought to underlie successful athletic performance as

delineated by contemporary theory. To select these

psychological skills, the three instruments described

earlier were reviewed, together with Vealey (1988),

Thomas and Over (1994) and Hardy et al. (1996a).

Vealey (1988) made the distinction between psycho-

logical skills and the methods or techniques used to

develop those skills. Sometimes, however, it is diYcult

to determine whether a construct should be regarded as

a skill or a method. For example, Vealey (1988)

described imagery as a method or technique, whereas

Hardy et al. (1996a) contended that imagery is a basic

psychological skill. Furthermore, Vealey (1988) listed

arousal control and attentional control as skills but

thought control as a method. It might be argued that

thought control ought to be considered as a skill that is

often developed through the use of more basic psycho-

logical skills such as self-talk. It seemed appropriate,

therefore, that the TOPS should target the most salient

psychological skills and techniques together with their

strategic use by athletes.

Although motivation has frequently been identiW ed as

a basic psychological skill, it is viewed by some as a trait

and by others as a transient, state-like characteristic that

is likely to change very easily. Similarly, the construct

`conW dence is frequently identiW ed as an important

skill in psychological skills training (Vealey, 1988). How-

ever, while it undoubtedly makes perfect sense to try to

measure an athletes conW dence before competition, it

is not clear what it would mean to say that an athlete

`used the skill of conW dence. Bandura (1977) proposed

that self-conW dence (or, more precisely, self-eYcacy)

is an aggregate expectation based upon an individuals

experience with similar situations, images of those

situations and feelings about them. Consequently, as

with motivation, the construct of conW dence was not

included in the TOPS, but the primar y skills that are

used to develop self-conW dence and motivation were.

In line with Banduras (1977) theory, these strategies

were: goal-setting, imagery, relaxation and self-talk.

Interactive or social variables such as teamwork, coach-

ability and interpersonal skills were excluded so as to

focus on the more generic intra-psychic factors under-

lying sports performance. A brief discussion of each of

the targeted constructs follows.

Attentional control. This factor was identiW ed in all the

research examined and is a central factor in cognitive

sport psychology (see, for example, Jones, 1990;

Boutcher, 1992; Hardy et al., 1996a; NideVer and Sagal ,

1998). Furthermore, Gould et al. (1989) reported that

80% of the sport psychology consultants they surveyed

conducted attention training with their clients.

Goal-setting. The use of goal-setting techniques is

regarded as one of the keys to motivation for better

athletic achievement (Burton, 1992; Hardy et al.,

1996a). Not surprisingly, therefore, sport psychology

consultants have reported using goal-setting more than

any other psychological intervention in their work with

athletes and coaches (Gould et al., 1989).

Imager y. This construct is widely agreed upon by

researchers as an important psychological skill in sport

(Vealey, 1988; Murphy and Jowdy, 1992; Hardy et al.,

1996a). Research also suggests that imagery is a skill that

can be practised and improved (George, 1986; Thomas

and Fogarty, 1997).

Relaxation and activation. Arousal control was identi-

W ed as an important psychological skill in most of the

sources that were reviewed. But research based upon

catastrophe theory (Hardy, 1990; Hardy and ParW tt,

1991) suggests that there is no reason to assume that the

skill of lowering high physiological arousal is the same

as the skill of raising it. Consequently, relaxation (or

the lowering of somatic anxiety) and activation (or the

raising of psychological and physiological energy) were

viewed as separate skills. By constructing separate

measures of these concepts, it was possible to examine

their relationship empirically.

Self-talk. The use of self-talk techniques was not

assessed in the instruments reviewed in the Intro-

duction, although self-talk appears to be closely related

to such constructs as attitude control (Loehr, 1986) and

thought control (Vealey, 1988). Whereas constructs

such as `attitude and `thought must be inferred

by participants, research shows that the amount and

quality of self-talk can be readily assessed by self and

by others (Van Raalte et al., 1994). Hardy et al. (1996a)

provide a review of the literature, which indicates that

the nature of ones self-talk is an important determinant

of athletic behaviour.

Emotional control. This construct has not been identi-

W ed directly in previous assessment instruments.

However, there is evidence that an ability to deal with

frustration and negative emotions is important for

competitive athletes. For example, Smith et al. (1995)

identiW ed `coping with adversity as an important factor

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

A

u

b

u

r

n

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

A

t

:

1

8

:

2

6

2

3

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

0

700 Thomas et al.

in successful athletic performance. Items loading on this

factor included `I maintain emotional control no matter

how things are going for me. Similarly, Thomas and

Over (1994) found that handling `negative emotions

and cognitions was an integral aspect of golf perfor-

mance. Their factor included items such as `I get angr y

and frustrated by a poor shot. Furthermore, the eVects

of a lack of control over certain speciW c emotions (e.g.

anxiety) upon performance are well-documented in the

sport psychology literature (Jones and Hardy, 1990;

Martens et al., 1990). Consequently, this construct was

included in the TOPS.

Automaticity. This factor emerged in only two of

the sources reviewed (Thomas and Over, 1994; Hardy

et al., 1996a). However, this construct is basic to

nearly all descriptions of expert performance, with

most cognitive theories of skill acquisition positing an

expert stage of development in which performance is

smooth and conscious cognitive control is minimal.

This stage has been called `autonomous (Fitts and

Posner, 1967), `procedural (Anderson, 1982) or

`automatic (Schneider and ShiVrin, 1977). Further-

more, the ability to perform at a high standard without

thinking about what one is doing is also central to

Csikszentmihalyis (1990) theory of `Xow, which has

been inXuential in recent sport psychology research

(Jackson, 1995).

Item pool development. An initial pool of 112 items was

developed by the authors to measure, in competition

and practice, athletes skills and strategies in each of the

eight areas outlined above. Items were written not only

to evaluate the athletes psychological skills in speciW ed

contexts (e.g. `I manage my self-talk eVectively during

competition), but also to measure their strategic use

of those skills (e.g. `I motivate myself to train through

positive self-talk; `I talk positively to myself to get the

most out of practice; `I say things to myself to help my

competitive performance). Feedback on the clarity of

the items obtained from athletes and sport psychologists

resulted in some modiW cations, additions and deletions.

The resulting pool of items was then given to a group of

10 applied sport psychology consultants, together with

the names and descriptions of the eight constructs that

the items were intended to represent. The consultants

were asked to conW rm the relevance of each item and

place it in one of the eight categories. Items that were

not considered relevant by all the consultants, and not

`correctly assigned by at least six of them, were deleted

from the pool. Slight modiW cations were also made to

some retained items based on feedback obtained from

the consultants.

The instrument used for the preliminar y investiga-

tions reported here consisted of 111 randomly ordered

items. In rating how frequently the item contents

applied in their own case, athletes used a 5-point scale

(1 = never; 2 = rarely; 3 = sometimes; 4 = often; 5 =

always). Participants were encouraged to be open and

honest in their responses, with the instructions stating

that `there are no right or wrong answers and that the

researchers expected variations in responses. Because of

the diversity of sports represented in the sample, the

instructions provided athletes with a glossary of eight

terms used in the items (competition, skill, perfor-

mance, routine, workout, and visualization/imagery/

rehearsal).

Participants

In generating the sample for this study, we sought to

include male and female athletes who were training and

competing in a wide variety of sports across a broad

range of performance standards. The W nal sample con-

sisted of 472 athletes (mean s: age 19.25 6.87 years)

drawn from three diVerent locations. Data were

obtained from 110 males (17.47 3.30 years) and 89

females (18.97 4.22 years) training at the Australian

Institute of Sport in Canberra. Data were also obtained

from 117 boys (16.10 1.38 years) active in sport who

attended a private high school in Sydney. Finally, data

were collected from 100 male athletes (24.23 9.85

years) and 56 female athletes (23.20 9.68 years) in the

Brisbane region.

At the time of the study, athletes in the sample had

been participating in 28 diVerent sports for 8.30 5.51

years. Responses provided by 461 of the 472 parti-

cipants indicated that 14.1% were competing inter-

nationally, 13.7% nationally, 8.7% at intercollegiate

or regional standard, 24.9% at junior national standard

and 11.5% at club or recreational standard. The other

27.1% of respondents included the sample of 117

boys in their W nal 2 years of high school and comprised

athletes who competed in inter-school sport.

Procedure

All athletes participated voluntarily in the study, the

instrument typically taking between 20 and 30 min to

complete. Athletes were made aware of the purpose of

administering the inventory and no W nancial induce-

ments were oVered for participation. Once the data

were collected and preliminary analyses conducted,

respondents received a summar y sheet describing

the eight constructs being targeted in the instrument,

together with their own proW le and group scores across

the intended subscales. Care was taken to emphasize

the tentative nature of this feedback, pending the results

of the thorough analyses of the data that are now

presented.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

A

u

b

u

r

n

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

A

t

:

1

8

:

2

6

2

3

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

0

Test of performance strategies 701

Results

Preliminar y analyses

Preliminary analysis of item responses revealed very few

missing data and no item was omitted by 10 or more of

the 472 participants. The entire response scale (`never

to `always) was used for each of the 111 items,

suggesting that the items were sensitive to individual

diVerences. For 107 of the 111 items, the absolute

values of skewness and kurtosis were within 1.0,

supporting the use of factor analysis using common

estimation procedures (Schutz and Gessaroli, 1993).

Furthermore, none of the remaining four items had an

absolute value of skewness greater than 1.3 and so all

items were retained in subsequent analyses.

Inventory items were divided into two scales, one con-

taining the 56 items referring to competition, and the

other containing the remaining 55 items referring to

practice. Exploratory factor analysis was used to assess

the dimensionality of each of these scales as recom-

mended for inventory development by Schutz and

Gessaroli (1993). Principal axis factoring was used

to extract factors based on the correlations among

variables, followed by oblique rotations with a delta

value of zero to allow for correlations among the factors.

Alternative rotated solutions were assessed on the basis

of the discontinuity (scree) principle for eigenvalues, as

well as the interpretability of factors.

Principal axis factor analysis of the competition

items produced 12 factors with eigenvalues greater

than 1.0, but three of these obliquely rotated factors

consisted of just one or two items with loadings of

0.30 or more. Consideration of the scree plot suggested

alternative solutions, with the number of factors varying

between 8 and 12. From these solutions we selected

the four items with the highest rotated loadings on

each of seven factors. We also selected the four items

that loaded highest on two other factors deW ning

energizing and psyching-up components of activation.

Thus, the 32 highest loading items of the original

56 competition-related items were retained for further

analysis.

The same procedures were adopted in analysing the

data from the 55 practice-related items. Principal axis

factor analysis again produced 12 factors with eigen-

values greater than 1.0, but one of these obliquely

rotated factors contained only two items with loadings

of 0.30 or more, and several other factors were not

readily interpretable. As the scree plot supported the

extraction of eight factors, we obtained alternative

solutions for 812 factors. By using the highest rotated

factor loadings in these solutions, we were able to select

four items for each of eight factors, retaining 32

practice-related items for further analysis.

Competition strategies

Factor analysis of the 32 retained items referring to

competition yielded eight factors with eigenvalues

greater than 1.0 and which accounted for 62.5% of

the variance. Table 1 lists the four items deW ning each

factor, all having obliquely rotated factor loadings

and itemtotal correlations of 0.30 or more. Mean

ratings on the 5-point scale, together with standard

deviations, are also shown for each item and the factor

as a whole.

Factor 1 (alpha coeYcient of 0.80) was labelled self-

talk, factor 2 (alpha of 0.79) emotional control, factor

3 (alpha of 0.74) automaticity, factor 4 (alpha of 0.78)

goal-setting, factor 5 (alpha of 0.79) imagery, factor

6 (alpha of 0.76) activation, factor 7 (alpha of 0.74)

negative thinking and factor 8 (alpha of 0.80) relaxation.

There was only one instance of an item loading

0.30 or more on two factors. Item 109 (`I keep my

thoughts positive during competitions) loaded -0.45

on negative thinking and 0.31 on self-talk. As the

internal reliability of the four-item self-talk subscale

was high (0.80) and not improved signiW cantly by the

addition of a W fth item (0.82), there appeared to be no

need to include responses to item 109 when calculating

self-talk scores.

Practice strategies

Factor analysis of ratings of the 32 items referring to

practice also yielded eight factors with eigenvalues

greater than 1.0, and these accounted for 60.4% of

the variance. Table 2 lists the four items deW ning each

factor, all with obliquely rotated factor loadings and

itemtotal correlations of 0.30 or more. Mean

ratings on the 5-point scale, together with standard

deviations, are again shown for each item and the factor

as a whole.

Factor 1 (alpha coeYcient of 0.78) was labelled

goal-setting, factor 2 (alpha of 0.72) emotional control,

factor 3 (alpha of 0.67) automaticity, factor 4 (alpha

of 0.78) relaxation, factor 5 (alpha of 0.81) self-talk,

factor 6 (alpha of 0.72) imagery, factor 7 (alpha of

0.73) attentional control and factor 8 (alpha of 0.66)

activation. Again, one item showed a cross-loading of

0.30 or more. Item 104 (`I practise a way to energize

myself ) loaded -0.34 on relaxation and 0.30 on acti-

vation. Inclusion of this item had very little eVect on

the internal reliability of the relaxation subscale (alpha

of 0.785 as compared to 0.781). On the other hand,

the internal reliability of the activation subscale in-

creased from 0.59 to 0.66 when item 104 was included.

Accordingly, item 104 was included on the activation

subscale, as had been intended when the item was

written.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

A

u

b

u

r

n

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

A

t

:

1

8

:

2

6

2

3

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

0

702 Thomas et al.

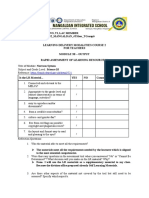

Table 1 Item loadings, itemtotal subscale correlations, mean ratings and standard deviations for competition strategies

Competition strategy Factor loading Itemtotal correlation Mean s

Factor 1: Self-talk

Talk positively to get the most out of competitions

Say things to help competitive performance

Manage self-talk eV ectively

Say speciWc cue words or phrases to help performance

Self-talk subscale

0.89

0.74

0.53

0.50

0.72

0.67

0.62

0.53

3.75 0.95

3.90 0.99

3.63 0.88

3.22 1.34

3.62 0.84

Factor 2: Emotional control

Emotions keep me from performing my best

Emotions get out of control under pressure

When something upsets me, my performance suV ers

Make a mistake, trouble getting concentration back on track

Emotional control subscale

-0.76

-0.57

-0.48

-0.43

0.59

0.60

0.60

0.59

2.35 0.97

2.14 0.85

2.70 0.96

2.49 0.87

3.58 0.72

Factor 3: Automaticity

Perform without consciously thinking about it

Dont think about performing much just let it happen

Perform on `automatic pilot

Play/perform instinctively with little conscious eVort

Automaticity subscale

0.73

0.63

0.62

0.55

0.59

0.54

0.52

0.47

3.03 1.05

2.99 1.05

2.91 1.06

3.32 0.99

3.06 0.77

Factor 4: Goal-setting

Set personal performance goals

Set very speciW c goals

Set speciWc result goals

Evaluate whether I achieve competition goals

Goal-setting subscale

0.83

0.66

0.66

0.46

0.69

0.63

0.53

0.50

3.97 0.95

3.81 0.98

3.91 0.96

3.66 1.04

3.84 0.77

Factor 5: Imagery

Imagine competitive routine before I do it

Rehearse the feel of performance in my imagination

Rehearse performance in my mind

Visualize competition going exactly the way I want it

Imagery subscale

0.70

0.68

0.65

0.41

0.67

0.59

0.61

0.54

3.60 1.03

3.40 1.08

3.73 1.01

3.71 0.99

3.61 0.82

Factor 6: Activation

Increase energy to just the right level

Do what needs to be done to get psyched up

Psych myself up to get ready to perform

Raise my energy level when necessary

Activation subscale

0.60

0.55

0.54

0.53

0.60

0.60

0.55

0.53

3.79 0.82

3.76 0.94

3.93 1.02

3.92 0.81

3.85 0.68

Factor 7: Negative thinking

Imagine screwing up

Self-talk is negative

Thoughts of failure

Keep my thoughts positive

Negative thinking subscale

0.59

0.52

0.49

-0.45

0.54

0.52

0.50

0.57

2.08 0.99

1.96 0.94

2.44 0.93

4.02 0.81

2.12 0.68

Factor 8: Relaxation

Able to relax if I get too nervous

Find it diYcult to relax when I am too tense

When the pressure is on, know how to relax

When I need to, I can relax to get ready to perform

Relaxation subscale

0.63

-0.55

0.53

0.46

0.65

0.59

0.64

0.56

3.52 0.86

2.79 0.93

3.56 0.87

3.63 0.85

3.48 0.69

Note: Item responses were reXected before calculation of emotional control subscale scores.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

A

u

b

u

r

n

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

A

t

:

1

8

:

2

6

2

3

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

0

Test of performance strategies 703

Table 2 Item loadings, itemtotal subscale correlations, mean ratings and standard deviations for practice strategies

Practice strategy Factor loading Itemtotal correlation Mean s

Factor 1: Goal-setting

Set realistic but challenging goals

Very speciW c goals

Set goals to help me use practice time eVectively

Dont set goals for practices, just go out and do it

Goal-setting subscale

0.75

0.61

0.60

-0.52

0.66

0.55

0.57

0.55

3.55 0.98

3.64 0.91

3.21 0.97

2.92 1.12

3.37 0.78

Factor 2: Emotional control

Trouble controlling emotions when things are not going well

Frustrated and emotionally upset when practice does not go well

When things are going poorly, stay in control of myself

emotionally

When I perform poorly I lose my focus

Emotional control subscale

-0.73

-0.66

0.53

-0.50

0.60

0.46

0.50

0.50

2.56 0.90

2.97 1.03

3.50 0.87

2.58 0.84

3.34 0.68

Factor 3: Automaticity

During practice sessions, seem to be in a Xow

Movements and skills seem to Xow naturally

Allow whole skill or movement to happen naturally without

concentrating on each part of the skill

Dont think about performing much just let it happen

Automaticity subscale

0.67

0.66

0.55

0.52

0.52

0.48

0.45

0.37

3.29 0.80

3.58 0.81

3.42 0.84

2.93 0.97

3.30 0.61

Factor 4: Relaxation

Use practice time to work on relaxation technique

Practise using relaxation techniques at workouts

Relax myself at practice to get ready

Practise a way to relax

Relaxation subscale

0.74

0.70

0.64

0.46

0.62

0.66

0.57

0.51

2.44 0.91

2.44 0.97

3.00 0.86

2.80 1.07

2.67 0.74

Factor 5: Self-talk

Talk positively to get the most out of practice

Motivate myself to train through positive self-talk

Say things to myself to help my practice performance

Manage self-talk eVectively

Self-talk subscale

0.68

0.62

0.60

0.60

0.68

0.61

0.59

0.61

3.55 0.93

3.61 1.03

3.41 1.00

3.29 0.98

3.47 0.79

Factor 6: Imagery

When I visualize my performance, I imagine watching myself as if

on a video replay

Visualize successful past performances

Rehearse my performance in my mind

When I visualize my performance, I imagine what it will feel like

Imagery subscale

0.61

0.55

0.55

0.52

0.52

0.50

0.55

0.49

3.10 1.17

3.40 1.01

3.08 1.00

3.42 1.08

3.25 0.79

Factor 7: Attentional control

Attention wanders while training

Trouble maintaining concentration during long practices

Focus attention eV ectively

Able to control distracting thoughts when training

Attentional control subscale

-0.71

-0.67

0.45

0.36

0.65

0.53

0.50

0.42

2.59 0.88

2.70 0.91

3.55 0.78

3.69 0.81

3.49 0.63

Factor 8: Activation

Trouble energizing if I feel sluggish

Practise energizing during training sessions

DiYculty increasing energy level during workouts

Practise a way to energize myself

Activation subscale

-0.54

0.49

-0.42

0.30

0.45

0.52

0.35

0.43

2.98 0.84

3.16 0.95

2.57 0.88

2.89 0.98

3.13 0.65

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

A

u

b

u

r

n

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

A

t

:

1

8

:

2

6

2

3

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

0

704 Thomas et al.

Correlations among strategies

Inspection of the coeYcients in Table 3 reveals

moderately strong correlations among many of the

strategies. Thus, for example, the skilful use of self-talk

in competition was positively associated with activation

(0.53, P < 0.001), imagery (0.51, P < 0.001), goal-

setting (0.43, P < 0.001), relaxation (0.39, P < 0.001)

and emotional control (0.28, P < 0.001) strategies.

Furthermore, strategic self-talk was inversely related to

negative thinking (-0.42, P < 0.001) and automaticity

(-0.13, P < 0.01).

A similar pattern of relationships is evident for these

strategies during practice. Self-talk correlated positively

with relaxation (0.52, P < 0.001), imagery (0.48,

P < 0.001), goal-setting (0.46, P < 0.001), activation

(0.45, P < 0.001), attentional control (0.38, P < 0.001)

and emotional control (0.13, P < 0.01). Self-talk was

unrelated to automaticity during practice, as indeed

were most other strategies.

The skilful use of self-talk techniques in competition

correlated strongly with the use of these techniques in

practice (0.69, P < 0.001). SigniW cant correlations

between the competition and practice contexts were

also noted for imagery (0.65, P < 0.001), emotional

control (0.56, P < 0.001), goal-setting (0.50, P <

0.001), activation (0.47, P < 0.001), automaticity

(0.44, P < 0.001) and relaxation (0.25, P < 0.001).

Negative thinking in competition was inversely re-

lated to both attentional control (-0.39, P < 0.001)

and emotional control (-0.44, P < 0.001) during

practice.

In summar y, athletes who use particular strategies in

competition, such as self-talk, imagery, goal-setting,

activation and relaxation, also tend to make use of the

other strategies measured. The same applies during

practice. Finally, there is considerable overlap in the use

of particular mental strategies across the two perform-

ance contexts.

Discriminant validity: Competition inventor y

DiVerences between the subgroups in the use of

psychological skills and strategies were analysed to

examine the validity of the subscales. Tables 4 and 5

show the competition subscale means and standard

deviations for males and females in each of the six

Table 3 Correlations between scores on the competition and practice strategies subscales

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1. Self-talk

2. Emotional control

3. Automaticity

4. Goal-setting

5. Imagery

6. Activation

7. Relaxation

8. Negative thinking

9. Attentional control

(0.69)

0.28

-0.13

0.43

0.51

0.53

0.39

-0.42

0.13

(0.56)

0.03

0.18

0.22

0.33

0.59

-0.52

0.00

0.11

(0.44)

-0.12

-0.10

-0.01

0.06

-0.03

0.46

0.13

-0.12

(0.50)

0.53

0.42

0.29

-0.26

0.48

0.10

0.00

0.47

(0.65)

0.50

0.30

-0.29

0.45

0.31

-0.02

0.45

0.45

(0.47)

0.44

-0.40

0.52

0.16

-0.02

0.46

0.46

0.45

(0.25)

-0.52

0.38

0.41

0.04

0.37

0.30

0.46

0.27

Note: Correlations among competition strategies are in the lower left diagonal; those for practice strategies are in the upper right diagonal; and

those for corresponding subscales are shown in parentheses. Correlations greater than 0.09 are statistically signiW cant (P < 0.05, two-tailed).

Table 4 Means and standard deviations for the competition strategies subscales for male athletes grouped by performance

standard

Competition

strategies

International

(n = 41)

National

(n = 31)

College and

regional

(n = 31)

Junior

national

(n = 71)

Recreational

(n = 30)

Other (e.g.

high school)

(n = 118)

Self-talk

Emotional control

Automaticity

Goal-setting

Imagery

Activation

Relaxation

Negative thinking

3.84 0.77

3.72 0.57

3.06 0.74

4.10 0.62

4.01 0.71

4.12 0.52

3.75 0.57

1.99 0.70

3.59 0.94

3.43 0.86

3.19 0.67

4.03 0.68

3.75 0.79

3.78 0.61

3.38 0.76

2.27 0.69

3.32 0.87

3.54 0.71

3.45 0.68

3.49 0.82

3.26 0.92

3.47 0.66

3.42 0.71

2.29 0.89

3.58 0.83

3.66 0.67

3.00 0.79

3.74 0.66

3.51 0.67

3.81 0.64

3.56 0.72

2.06 0.65

3.39 0.70

3.53 0.59

3.43 0.79

3.43 0.74

3.12 0.69

3.58 0.66

3.38 0.58

2.07 0.50

3.79 0.78

3.56 0.80

2.99 0.77

3.89 0.81

3.64 0.81

3.93 0.73

3.48 0.67

2.09 0.63

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

A

u

b

u

r

n

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

A

t

:

1

8

:

2

6

2

3

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

0

Test of performance strategies 705

Table 5 Means and standard deviations for the competition strategies subscales for female athletes grouped by performance

standard

Competition strategies

International

(n = 24)

National

(n = 32)

Junior national

(n = 44)

Recreational

(n = 23)

Self-talk

Emotional control

Automaticity

Goal-setting

Imagery

Activation

Relaxation

Negative thinking

3.48 1.05

3.85 0.63

3.18 0.80

4.14 0.73

3.93 0.78

4.09 0.64

3.95 0.70

1.83 0.56

3.34 0.82

3.53 0.71

2.94 0.71

3.89 0.76

3.65 0.82

3.77 0.56

3.39 0.54

2.10 0.73

3.94 0.69

3.73 0.64

2.70 0.66

4.09 0.66

3.90 0.72

4.14 0.57

3.59 0.62

2.17 0.70

3.48 0.93

3.24 0.52

3.05 0.82

3.54 0.90

3.29 0.88

3.52 0.63

3.02 0.54

2.46 0.68

subgroups deW ned by current performance standard.

Preliminary age sex multivariate analyses of variance

(MANOVA) were performed on both the competition

and practice data to determine if it was necessary

to control for their eVects in the main performance

standard analyses. For these age sex analyses, the

sample was divided into three age groups in such a way

that each contained suYcient participants for the results

to be meaningful. Group 1 comprised those athletes

younger than 17 years of age (n = 134), Group 2 those

athletes aged 1719 years (n = 215) and Group 3 those

athletes aged 20 years and older (n = 119).

For the competition data, the age sex MANOVA

revealed a main eVect for age (approx. F

16,910

= 2.88,

P < 0.001), which subsequent univariate analyses of

variance (ANOVA) suggested was due to signiW cant

diVerences in automaticity (F

2,462

= 3.50, P < 0.05),

imagery (F

2,462

= 3.91, P < 0.05) and activation (F

2,462

=

12.37, P < 0.001). Follow-up Tukey tests showed that,

in general, older performers used imagery and acti-

vation strategies less in competition than younger

performers, and reported more automaticity. The

age sex MANOVA also revealed a main eVect for sex

in the competition data (exact F

8,455

= 2.31, P < 0.05).

Subsequent univariate analyses of variance suggested

that this was due to signiW cant diVerences in auto-

maticity (F

1,462

= 4.71, P < 0.05) and imagery (F

1,462

=

3.78, P = 0.05). Examination of the cell means showed

that males scored higher on automaticity, but lower

on imagery, than females. The age sex MANOVA

did not reveal a signiW cant interaction eVect (approx.

F

16,910

= 0.98, P > 0.05).

In light of the above W ndings, the eVects of current

performance standard on the strategic use of psycho-

logical skills in competition were examined using

separate single-factor multivariate analyses of co-

variance (MANCOVA) for the male and female data

with age as a covariate in each case. Sex was not

included as a second independent variable in the

MANCOVA because there were not enough females in

the college/regional and other/high school categories.

For the males, the overall MANCOVA was signiW cant

(approx. F

40,1345

= 1.58, P < 0.02), with univariate

analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) suggesting that this

was due to signiW cant diVerences in automaticity

(F

5,315

= 2.40, P < 0.05), goal-setting (F

5,315

= 4.24,

P < 0.01), imagery (F

5,315

= 5.34, P < 0.001) and acti-

vation (F

5,315

= 2.64, P < 0.05). Boneferroni follow-up

tests indicated that other/high school athletes scored

signiW cantly lower than college/regional athletes on

automaticity. The diVerence between other/high school

athletes and club/recreational athletes was also very

close to signiW cant. International athletes, national

athletes and other/high school athletes all scored sig-

niW cantly higher than club/recreational athletes on

goal-setting, with international athletes also scoring

signiW cantly higher than college/regional athletes.

International athletes scored signiW cantly higher than

junior national, college/regional and club/recreational

athletes on imagery, with national athletes and other/

high school athletes also scoring signiW cantly higher

than club/recreational athletes. Finally, international

athletes scored higher than college/regional athletes

and club/recreational athletes on activation, with other/

high school athletes also scoring signiW cantly higher

than college/regional athletes. Male international and

national standard athletes, together with the other

(largely high school) athletes, tended to score higher

than the college/regional and club/recreational athletes

on most subscales. The exception was on automaticity,

where the reverse occurred (see Table 4).

For female athletes, only four standards of com-

petitive performance were examined: international,

national, junior national and club/recreational. The

overall MANCOVA was signiW cant (approx. F

24,322

=

3.27, P < 0.001) with univariate analyses of covariance

suggesting that this was due to signiW cant diVerences

in self-talk (F

3,118

= 4.16, P < 0.01), emotional control

(F

3,118

= 3.98, P < 0.05), automaticity (F

3,118

= 3.83,

P < 0.05), goal-setting (F

3,118

= 4.07, P < 0.01), imagery

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

A

u

b

u

r

n

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

A

t

:

1

8

:

2

6

2

3

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

0

706 Thomas et al.

(F

3,118

= 3.14, P < 0.05), activation (F

3,118

= 5.47, P <

0.01), negative thinking (F

3,118

= 3.45, P < 0.05) and

relaxation (F

3,118

= 9.65, P < 0.001). Bonferroni follow-

up tests indicated that junior national athletes scored

signiW cantly higher than national athletes on self-talk.

International athletes and junior national athletes

scored signiW cantly higher than club/recreational

athletes on emotional control. There were no signiW cant

diVerences between any of the groups for automaticity.

International and junior national athletes scored sig-

niW cantly higher than club/recreational athletes on

goal-setting, imagery, activation and relaxation. Inter-

national athletes also scored signiW cantly higher than

national athletes on relaxation. Finally, international

athletes scored signiW cantly lower than club/recreational

athletes on negative thinking. The female international

and junior national athletes tended to score higher than

the club/recreational athletes on all subscales except

negative thinking, where they scored lower, and

automaticity, where there was no clear pattern (see

Table 5).

Discriminant validity: Practice inventory

Tables 6 and 7 show the practice subscale means and

standard deviations for males and females in each of

the six subgroups deW ned by current performance

standard. The preliminary age sex MANOVA on the

practice data revealed a main eVect for age (approx.

F

16,910

= 2.72, P < 0.001), which subsequent univariate

analyses of variance suggested was due to signiW cant

diVerences in emotional control (F

2,462

= 4.41, P <

0.05), imagery (F

2,462

= 2.89, P < 0.06) and activation

(F

2,462

= 4.40, P < 0.05). Follow-up Tukey tests showed

that, in general, older performers used emotional

control strategies more, but imagery and activation

strategies less, than younger performers during practice.

The age sex MANOVA also revealed a main eVect for

sex in the practice data (exact F

8,455

= 2.33, P < 0.05).

Subsequent univariate analyses of variance suggested

that this was due to a marginally signiW cant diVerence

in goal-setting (F

1,462

= 3.71, P < 0.06), a signiW cant

diVerence in activation (F

1,462

= 4.26, P < 0.05) and a

marginally signiW cant diV erence in attentional control

(F

1,462

= 3.67, P < 0.06). Examination of the cell means

showed that males scored lower than females on all

three subscales. The age sex MANOVA did not reveal

a signiW cant interaction eVect (approx. F

16,910

= 0.77,

P > 0.05).

In light of these W ndings, the eVects of current per-

formance standard on the strategic use of psychological

skills in practice were agai n examined using separate

Table 6 Means and standard deviations for the practice strategies subscales for male athletes grouped by performance standard

Practice

strategies

International

(n = 41)

National

(n = 31)

College and

regional

(n = 31)

Junior

national

(n = 71)

Recreational

(n = 30)

Other (e.g.

high school)

(n = 118)

Self-talk

Emotional control

Automaticity

Goal-setting

Imagery

Activation

Relaxation

Attentional control

3.67 0.72

3.44 0.69

3.34 0.52

3.51 0.76

3.58 0.68

3.06 0.69

3.11 0.69

3.65 0.52

3.57 0.64

3.38 0.76

3.48 0.70

3.41 0.68

3.37 0.77

2.94 0.54

2.79 0.76

3.41 0.76

3.19 0.71

3.52 0.62

3.52 0.58

2.99 0.80

2.94 0.92

2.84 0.54

2.45 0.73

3.25 0.69

3.42 0.77

3.41 0.68

3.26 0.62

3.35 0.71

3.32 0.55

3.14 0.58

2.52 0.68

3.40 0.61

3.35 0.81

3.54 0.55

3.33 0.73

3.08 0.80

2.86 0.84

2.98 0.60

2.63 0.78

3.42 0.53

3.57 0.84

3.18 0.73

3.26 0.70

3.35 0.87

3.22 0.77

3.20 0.79

2.57 0.76

3.47 0.67

Table 7 Means and standard deviations for the practice strategies subscales for female athletes grouped by performance

standard

Practice strategies

International

(n = 24)

National

(n = 32)

Junior national

(n = 44)

Recreational

(n = 23)

Self-talk

Emotional control

Automaticity

Goal-setting

Imagery

Activation

Relaxation

Attentional control

3.43 0.90

3.54 0.66

3.36 0.52

3.72 0.79

3.43 0.76

3.30 0.61

2.60 0.62

3.60 0.71

3.34 0.74

3.27 0.67

3.27 0.50

3.59 0.74

3.13 0.80

3.16 0.54

2.83 0.58

3.63 0.60

3.62 0.70

3.30 0.63

3.08 0.50

3.53 0.63

3.55 0.83

3.37 0.52

2.92 0.75

3.72 0.38

3.22 0.86

3.24 0.58

3.34 0.42

3.33 0.65

2.89 0.81

3.11 0.63

2.58 0.65

3.25 0.57

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

A

u

b

u

r

n

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

A

t

:

1

8

:

2

6

2

3

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

0

Test of performance strategies 707

single-factor multivariate analyses of covariance for

the male and female data with age as a covariate in

each case. For the males, the overall MANCOVA was

signiW cant (approx. F

40,1345

= 2.33, P < 0.001), with

univariate analyses of covariance suggesting that this was

due to signiW cant diVerences in automaticity (F

5,315

=

2.73, P < 0.05), goal-setting (F

5,315

= 2.25, P < 0.05),

imagery (F

5,315

= 3.47, P < 0.01) and relaxation (F

5,315

=

4.71, P < 0.001). Bonferroni follow-up tests showed no

signiW cant diVerences in automaticity or goal-setting.

However, the international, national, junior national

and other/high school athletes scored somewhat higher

than the club/recreational and college/regional athletes

on goal-setting. International athletes also scored

signiW cantly higher than club/recreational athletes and

college/regional athletes on imagery, and signiW cantly

higher than junior national, other/high school, and

college/regional athletes on relaxation. Male inter-

national and national standard athletes, and to a lesser

extent the other (largely high school) athletes, tended

to score higher than the college/regional and club/

recreational athletes on most subscales. The exception

was on automaticity, where no clear pattern emerged

(see Table 6).

For the female athletes, the same four standards of

competitive performance were examined as previously:

international, national, junior national and club/

recreational. The overall MANCOVA was again signiW -

cant (approx. F

24,322

= 1.65, P < 0.05), with univariate

analyses of covariance suggesting that this was due to

signiW cant diVerences in automaticity (F

3,118

= 2.82, P <

0.05), imagery (F

3,118

= 3.20, P < 0.05) and attentional

control (F

3,118

= 2.97, P < 0.05). However, the only sig-

niW cant diVerences identiW ed by Bonferroni follow-up

tests were that junior national athletes scored higher

than club/recreational athletes on imagery and atten-

tional control. No signiW cant diVerences were identiW ed

for automaticity. Female international and junior

national standard athletes tended to score higher than

the club/recreational athletes on all subscales except

automaticity and relaxation. On automaticity the junior

nationals scored lowest, while on relaxation the inter-

national athletes had almost the same mean as the

club/recreational athletes (see Table 7).

Discussion

Exploratory factor analyses of the Test of Performance

Strategies yielded very clear factor structures for

both the competition and the practice items. The eight

factors hypothesized to underlie the items were: goal-

setting, relaxation, activation, imagery, self-talk,

attentional control, emotional control and automaticity.

In the practice data, all eight of these factors were

obtained. In the competition data, seven of the eight

hypothesized factors were identiW ed, with negative

thinking replacing attentional control for the eighth

factor. The substitution of attentional control by nega-

tive thinking in competition is not unreasonable given

that negative thinking may well be the metacognitive

manifestation of a lack of attentional control. However,

an interesting feature of the exploratory factor analyses

of the competition data was that, despite using several

diVerent extraction and rotation procedures, the atten-

tional and emotional control items refused to separate

into two factors. Indeed, even in the W nal solution of

the factor analyses, the fourth item selected for the

emotional control subscale reXects diYculties in re-

instating concentration after a mistake. Furthermore, as

might be expected under such circumstances, emotional

control was quite strongly (negatively) correlated with

negative thinking in the competition data and quite

strongly (positively) correlated with attentional control

in the practice data. The data seem to be oVering a fairly

clear message that good attentional control and con-

centration is diYcult without good emotional control.

The W ndings of the factor analyses, together with the

descriptive statistics presented for each subscale, clearly

support previous literature (Loehr, 1986; Mahoney

et al., 1987; Vealey, 1988; Nelson and Hardy, 1990;

Thomas and Over, 1994; Smith et al., 1995; Hardy

et al., 1996a) in identifying the use of motivational

(e.g. self-talk and goal-setting), imaginal, relaxation,

attentional control and emotional control strategies as

an important feature of athletes psychological prepar-

ation for competition. However, the present data show

that athletes also make use of such strategies in training.

Furthermore, as one might expect, the use of certain

strategies in training was generally associated with their

use in competition.

One question remaining was whether activation (the

raising of psychological and physiological energy)

was the opposite of relaxation (the lowering of somatic

anxiety) or orthogonal to it. The items generated for

the TOPS also included the somewhat broader concept

of emotional control rather than just anxiety control.

Activation emerged as an independent factor, but

correlated with relaxation and emotional control in both

factor analyses. This suggests that there is some overlap

in athletes use of these three diVerent types of strategy,

but that high ability in the use of one type of strategy

does not necessarily imply high ability in the other two

areas. The W ndings in relation to diVerences in these

strategies between subgroups provide further support

for such a view. Although an extensive literature exists

on relaxation and emotional control (see, for example,

Greenspan and Feltz, 1989; Gould and Udry, 1994),

much less is known about appropriate strategies for

enhancing activation (Hardy et al., 1996a).

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

A

u

b

u

r

n

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

A

t

:

1

8

:

2

6

2

3

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

0

708 Thomas et al.

Another interesting feature of the correlations among

the subscales of the TOPS was the strength of the rela-

tionships obtained. There were similar patterns in the

use of the basic psychological skills of goal-setting,

imagery and relaxation (see Vealey, 1988; Hardy et al.,

1996a), plus the possibly more advanced psychological

skill of activation, in both practice and competition. The

fact that self-talk was quite strongly correlated with all

the other subscales except automaticity during both

practice and competition is particularly interesting.

Self-talk appears to be a relatively under-researched

area in sport psychology, and few controlled studies

have been performed on how athletes self-talk might be

improved (see Hardy et al., 1996a). Although causality

clearly cannot be inferred from these correlations,

they provide some support for cognitive-behavioural

interventions which use self-talk techniques to change

athletes feelings and improve performance (Zinsser

et al., 1998). Recent evidence of the beneW ts of work

in this area was provided by Thomas and Fogarty

(1997), who reported a signiW cant reduction in

golfers negative emotions and cognitions, and improve-

ment in their performance, after imagery and self-talk

training.

The analyses of variance of the competition data

indicated that older performers reported less use of

imagery and activation strategies, but more auto-

maticity than their younger counterpar ts; males

reported less imagery but more automaticity than

females. They also showed that both male and female

international athletes generally used a wider range of

psychological strategies than those of a lower standard,

in particular college, regional and recreational perfor-

mers. When the eVects of age were removed from the

data, these diVerences were signiW cant for goal-setting,

imagery and activation in the males, and for self-talk,

emotional control, goal-setting, imagery, activation,

negative thinking and relaxation in the females. Fur-

thermore, although there were signiW cant diVerences

between ability groups in automaticity, neither male nor

female international performers reported more auto-

maticity than other performers.

These W ndings are broadly in line with the previous

literature (Mahoney et al., 1987; Thomas and Over,

1994; Smith et al., 1995; Hardy et al., 1996a), except

that one might reasonably have expected international

performers to have greater automaticity than the other

athletes. One possible explanation for this counter-

intuitive W nding for automaticity is that the subscale

automaticity is in fact mislabelled. It is possible that

some athletes (possibly from certain sports) confuse the

genuine automaticity that is supposed to be tapped by

the automaticity items with a generally disorganized

or laissez-faire approach to competition. This inter-

pretation is supported by the very weak or non-existent

correlations that automaticity had with the other

subscales.

On the other hand, the pattern of correlations pro-

vides support for the view that genuine automaticity is

independent of athletes use of psychological skills and

strategies measured on other subscales. Automaticity

is associated with peak performance, `playing in the

zone and the experience of Xow (Cohn, 1991; Moore

and Stevenson, 1991; Jackson, 1995). Psychological

skills training is often conducted to help athletes attain

automaticity and perform at their peak. On many

occasions, however, they do not experience such a state

in competition or in practice, and rely instead on con-

scious eVort and strategic use of psychological skills to

perform well.

Automaticity correlated strongly with mental prepar-

ation, concentration and a lack of negative thoughts in

Thomas and Overs (1994) study of golfers. It may

be that automaticity is more important for some sports

(e.g. golf) than others, and that most of the present

sample participated in sports in which performers have

to make use of both implicit and explicit knowledge to

perform optimally (Hardy et al., 1996a,b). All of these

explanations of the automaticity W nding are worthy of

further research.

Two other W ndings from the analyses of variance

deserve further comment. First, the smaller number

of signiW cant diVerences between male international

performers and other male performers is counter-

intuitive, particularly their use of self-talk and their

ability to control negative thinking, and runs counter

to some previous W ndings (e.g. Mahoney et al., 1987;

Thomas and Over, 1994). However, it does not run

counter to all other W ndings (e.g. Smith et al., 1995;

Smith and Christensen, 1995). Perhaps elite male

performers have lower levels of trait anxiety than their

non-elite counterparts (Krohne and Hindel, 1988), or

naturally interpret their anxiety symptoms positively

(Mahoney and Avener, 1977; Jones et al., 1994; Jones

and Swain, 1995); therefore, they do not need to

consciously use strategies to enhance positive self-talk.

However, such an explanation does not account for the

lack of signiW cant diVerences in negative thinking.

An alternative explanation is that elite Australian male

performers are more reluctant than elite Australian

female performers to admit that they experience any

psychological diYculties in competition or use psycho-

logical strategies to counter such diYculties. This

explanation is consistent with previous W ndings that

males often report lower state and trait competitive

anxiety than females (Martens et al., 1990; Jones et al.,

1991).

Second, in the male data, the high school/other

groups appeared to align much more closely with the

national and international athletes than with the club/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

A

u

b

u

r

n

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

A

t

:

1

8

:

2

6

2

3

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

0

Test of performance strategies 709

recreational and college/regional athletes. This some-

what counterintuitive eVect could be a result of selec-

tion bias. The high school/other sample was largely

made up of boys from a single private high school

in Sydney. The simplest explanation of the test per-

formance of these boys is that they may have received

some psychological skills training, either formally or

informally, as a result of the school that they attended,

and that such training was not available to other

males in the club/recreational and college/regional

samples.

The analyses of variance of the practice data indicated

that older performers used emotional control strategies

more, but imagery and activation strategies less, than

younger performers, and that males used goal-setting,

activation and attentional control strategies less than

females. They also showed that, as with the competition

data, international performers generally practised

using their psychological skills more in training than

their non-elite counterparts. When the eVects of age

were removed from the data, these diV erences were

signiW cant for goal-setting, imagery and relaxation in

the males, and for imagery and attentional control in the

females. Again, as with the competition data, although

there were signiW cant diVerences in automaticity be-

tween ability groups, neither male nor female inter-

national performers reported more automaticity than

other performers. The W ndings that male international

performers practised the basic psychological skills of

goal-setting, imagery and relaxation more in training

than college, regional and recreational performers is

interesting, because it suggests that performers of a high

standard may generally have better developed psycho-

logical skills and strategies for competition because

they practise their basic psychological skills in training.

This possibility is important because it parallels the

received view from coaches with respect to physical

skills; that is, performers of a high standard need to have

good `basics. Again this W nding is worthy of further

investigation using a stronger design.

Other issues involving the relationship between

practice and competition also warrant further con-

sideration. The TOPS subscales measure a relatively

common set of skills or strategies in the two contexts.

There may be other psychological skills that are

exclusive to practice or competition, or the same skill

may be used in diVerent ways or to diVerent extents in

the two contexts. The signiW cant correlations between

competition and practice subscales do not imply that

the skills or strategies were used to the same extent in

those contexts. The subscale means suggest greater

use of skills in competition than during practice, but

caution is required, as the items comprising the respec-

tive subscales are not identical. The subscale means may

also have been inXuenced by other factors, including

whether the participants completed the inventory in or

out of season. Further research needs to explore both

the similarities and diVerences between these contexts.

In conclusion, we have presented preliminary data on

the development of an instrument to measure athletes

use of psychological skills and strategies both in training

and in competition. These initial data are encouraging

and suggest that the Test of Performance Strategies

is well-suited to assessing the eVectiveness of psycho-

logical skills training interventions. Further work is

needed to examine the reliability of the factor structure

of the TOPS using conW rmatory factor analysis, to

test its concurrent and discriminant validity, to explore

possible sport-speciW c diVerences in the subscales,

particularly those where the W ndings were counter-

intuitive (negative thinking and automaticity), and to

examine the link between the practice of basic psycho-

logical skills in training and the eVectiveness of

advanced psychological strategies in competition.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by GriYth University and the

United States Olympic Training Center, Colorado Springs.

We would like to thank Suzie TuV ey, Dorsey Edmonson,

Sean McCann and JeV Bond for their contributions to this

project.

References

Anderson, J.A. (1982). Acquisition of cognitive skill. Psycho-

logical Review, 89, 369406.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-eYcacy: Toward a unifying theory

of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191215.

Boutcher, S.H. (1992). Attention and athletic performance:

An integrated approach. In Advances in Sport Psychology

(edited by T.S. Horn), pp. 251266. Champaign, IL:

Human Kinetics.

Burton, D. (1992). The Jekyll/Hyde nature of goals: Recon-

ceptualizing goal setting in sport. In Advances in Sport

Psychology (edited by T.S. Horn), pp. 267297.

Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Chartrand, J.M., Jowdy, D.P. and Danish, S.J. (1992). The

Psychological Skills Inventory for Sports: Psychometric

characteristics and applied implications. Jour nal of Sport

and Exercise Psychology, 14, 405413.