Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Legends Are Forever v. Nike PDF

Uploaded by

Mark Jaffe0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

219 views17 pagesU.s. District Court in new york grants Motion for summary judgment. Plaintiff is a baseball-themed souvenir shop in cooperstown, new york. Defendant's website was shut down in September 2012.

Original Description:

Original Title

Legends are Forever v. Nike.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentU.s. District Court in new york grants Motion for summary judgment. Plaintiff is a baseball-themed souvenir shop in cooperstown, new york. Defendant's website was shut down in September 2012.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

219 views17 pagesLegends Are Forever v. Nike PDF

Uploaded by

Mark JaffeU.s. District Court in new york grants Motion for summary judgment. Plaintiff is a baseball-themed souvenir shop in cooperstown, new york. Defendant's website was shut down in September 2012.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 17

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

LEGENDS ARE FOREVER, INC.,

Plaintiff,

-against- 3:12-CV-1495 (LEK/DEP)

NIKE, INC.,

Defendant.

MEMORANDUM-DECISION and ORDER

I. INTRODUCTION

Plaintiff Legends are Forever, Inc. (Plaintiff or LAF), commenced this trademark suit

against Defendant Nike, Inc. (Defendant or NIKE), on September 27, 2012. Dkt. No. 1

(Complaint). Presently before the Court is Defendants Motion for summary judgment. Dkt No.

30 (Motion). For the following reasons, the Motion is granted.

II. FACTS

1

A. Plaintiffs Business

Plaintiff is a baseball-themed souvenir shop located in Cooperstown, NY. Dkt. No. 32

(Statement of Material Facts or SMF) 1. Cooperstown is the home of the National Baseball

Hall of Fame, and is therefore a tourist destination. Id. 2. Plaintiffs storefront sign prominently

advertises Major League Baseball apparel, souvenirs related to Cooperstown, and autographed

baseball memorabilia. Id. 3.

LAFs owner and president is Jeffrey Foster (Jeff Foster), who founded the store in 2001

Plaintiff did not respond to Defendants Statement of Material Facts. See Docket.

1

Accordingly, pursuant to Local Rule 7.1(a)(3), the facts set forth in Defendants Statement of

Material Facts are deemed admitted and form the basis of this section.

after owning another baseball-related retail business in Cooperstown. Id. 4-6. Plaintiffs

business is roughly 95% baseball-related products and autographed memorabilia. Id. 11. Plaintiff

previously sold its products through a website, which it shut down in September 2012. Id. 12-13.

Jeff Foster came up with the phrase Legends Are Forever to evoke the feelings and

emotions surrounding baseball history. Id. 19-21. In 2007, Plaintiff applied to register the mark

LEGENDS ARE FOREVER. Id. 24. This application was abandoned and revived twicein

December 2008 and June 2009before registration number 3,731,889 was issued in December

2009 (the Asserted Mark). Id. Plaintiff has not used a registered trademark symbol on any of its

products bearing the Asserted Mark, and there is no set style used by Plaintiff for displaying the

Asserted Mark. Id. 25-26.

Plaintiffs typical customer is a visitor to Cooperstown who wants a souvenir or memento of

their trip. Id. 37. Most of these visitors also visit the Baseball Hall of Fame. Id. Plaintiff does

not currently do any advertising. Id. 39. Plaintiff previously had former baseball players visit the

store to sign autographs, but otherwise confined its marketing activities to local advertisements and

Facebook postings. Id. 39-40. Plaintiff also paid pay-per-click fees with various internet

search engines and shopping sites. Id. 41. Plaintiff would list its memorabilia and merchandise

on various shopping websites and pay a fee each time a prospective customer clicked on a product

listing. Id.

Plaintiffs business has been declining in recent years, and it recently downsized to a smaller

space. Id. 48. As a result, Plaintiff may attempt to sell more apparel in place of autographed

baseball memorabilia, but has not taken any active steps to do so. Id.

2

B. Defendants Business

Defendant is the largest seller of athletic footwear and apparel in the world. Id. 51. Its

principal business is the design, development, and worldwide marketing and sale of athletic

footwear, equipment, accessories, and services. Id. Defendants NIKE mark and NIKE swoosh

logo have been recognized as famous under the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. 1125(c). Id. 52 (citing

NIKE, Inc. v. Top Brand Co., No. 00-CV-8179, 2004 WL 165859, at *9 (S.D.N.Y. July 13, 2005)

and NIKE, Inc. v. Variety Wholesalers, Inc., 274 F. Supp. 2d 1352, 1372 (S.D. Ga. 2003)).

Defendant sells its products through its own retail stores and internet websites, and through a mix of

independent distributors and licensees.

C. Kobe Bryant: Black Mamba

In January 2011, Defendant aired a six-minute film titled The Black Mamba. SMF 54.

The film starred professional basketball player Kobe Bryant (Kobe), and was part of a

promotional campaign surrounding Defendants release of a Kobe-themed shoe. Id. 54, 56. The

film concludes with Kobe questioning the films directorRobert RodriguezSo how should it

end? Id. 58. Rodriguez responds, Black Mamba doesnt end. Heroes come and go . . . , and

Kobe interrupts and completes the sentence, but legends are forever. Id.

After seeing the film in November 2011, Jeff Foster approached Defendant on behalf of

Plaintiff to see if Defendant was interested in paying for use of the phrase legends are forever. Id.

59, 61. Matthew Foster (Matt Foster), Jeffs brother and an employee of Plaintiff from 2009

until 2013, also contacted Defendant regarding the possible lease or sale of the Asserted Mark. Id.

7, 62. Defendant did not pursue these offers. Id. 63.

3

D. The Shirt

In April 2011, Defendant designed apparel for its Kobe Bryant summer product line. Id.

65. The phrase legends are forever was initially propsed for a t-shirt in the line, and preliminary

designs, graphics, and ten salesman samples of a t-shirt with the phrase were created. Id. The ten

salesman samples were not intended for sale and were never sold or offered for sale by Defendant.

Id.

Defendant rejected the phrase legends are forever prior to production and sale of the t-

shrts in the Kobe Bryant line, and instead selected the phrase legends live forever for t-shirt style

No. 465630 (the Black Mamba Shirt). Id. 66. Although the phrase legends are forever was

never used on any product sold or offered for sale by Defendant, the proposed phrase was

inadvertently retained in Defendants internal database. Id. 68. The retention of this language

may account for any use of the phrase legends are forever in internet descriptions of the legends

live forever Black Mamba Shirt. Id.

According to Matt Foster, in June 2012, a customer walked into Plaintiffs store wearing a

shirt that said either legends are forever or legends live forever. Id. 70. Matt Foster asked the

customer about the shirt, and the customer explained that it was a Black Mamba shirt and identified

it as a Kobe Bryant item. Id. 70-71.

At some point, Jeff Foster obtained a NIKE-produced t-shirt with the phrase legends are

forever printed on it (the Accused Shirt). Id. 73. He obtained the Accused Shirt from an

individual seller through ebay.com, an online auction site. Id. 73. The Accused Shirt lacked a

price tag and included a white tag stating: This is a sample. Id. The Fosters attempted to

purchase additional NIKE shirts with this phrase but were unable to find any. Id. 79.

4

The Fosters were able to buy Black Mamba Shirtsi.e., those with the phrase Legends

Live Forever. Id. 80. Plaintiff contends that online retailers selling these shirts described them

with the style name Legends Are Forever Kobe Bryant Shirt, and may have included graphics

from the allegedly infringing shirt. Id. 82.

E. Procedural History

Plaintiff commenced this action on September 27, 2012, asserting claims of: (1) federal

trademark infringement under 15 U.S.C. 1114; (2) common law trademark infringement and

unfair competition; (3) federal unfair competition and false designation of origin under 15 U.S.C.

1125; (4) federal trademark dilution under 15 U.S.C. 1125; and (5) violation of New York

General Business Law 349. Compl. 19-60. Plaintiff seeks declaratory and monetary relief. Id.

Discovery in this case progressed at a disturbingly slow pace, Dkt. No. 38 (Fees Order)

at 2, culminating in an Order by the Honorable David E. Peebles, U.S. Magistrate Judge, directing

Plaintiff to pay Defendant $12,332.82 in attorneys fees, id. at 16. Defendant filed its Motion for

summary judgment on November 1, 2013, Mot.; Dkt. No. 31 (Memorandum), but the disposition

of the Motion was delayed by Plaintiffs erroneous appeal of the Fees Order to the Second Circuit,

June 3, 2014 Text Order; Dkt. Nos. 41 (Appeal); 50. The Appeal was stricken and withdrawn in

June 2014. June 3, 2014 Text Order; Dkt. No. 50.

Plaintiff Responded to Defendants Motion, but, as noted supra, Plaintiff failed to respond to

Defendants Statement of Material Facts. Dkt. No. 37 (Response). Defendant filed a Reply. Dkt.

No. 39 (Reply).

III. LEGAL STANDARD

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56(a) instructs a court to grant summary judgment if there

5

is no genuine dispute as to any material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of

law. Although [f]actual disputes that are irrelevant or unnecessary will not preclude summary

judgment, summary judgment will not lie if . . . the evidence is such that a reasonable jury could

return a verdict for the nonmoving party. Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 248

(1986); see also Taggart v. Time, Inc., 924 F.2d 43, 46 (2d Cir. 1991).

The party seeking summary judgment bears the burden of informing the court of the basis

for the motion and of identifying those portions of the record that the moving party claims will

demonstrate the absence of a genuine issue of material fact. Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317,

323 (1986). If the non-moving party will bear the burden of proof on a specific issue at trial, the

moving party may satisfy its own initial burden by demonstrating the absence of evidence in support

of an essential element of the non-moving partys claim. Id. If the moving party carries its initial

burden, then the non-moving party bears the burden of demonstrating a genuine issue of material

fact. Id. This requires the nonmoving party to do more than simply show that there is some

metaphysical doubt as to the material facts. Matsushita Elec. Indus. Co. v. Zenith Corp., 475 U.S.

574, 586 (1986). At the same time, a court must resolve all ambiguities and draw all reasonable

inferences in favor of the nonmoving party. Reeves v. Sanderson Plumbing Prods., Inc., 530 U.S.

133, 150 (2000); Nora Beverages, Inc. v. Perrier Grp. of Am., Inc., 164 F.3d 736, 742 (2d Cir.

1998). A courts duty in reviewing a motion for summary judgment is carefully limited to finding

genuine disputes of fact, not to deciding them. Gallo v. Prudential Residential Servs., 22 F.3d

1219, 1224 (2d Cir. 1994).

6

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Federal Trademark Infringement and Unfair Competition Claims

Plaintiff asserts a claim of trademark infringement under 15 U.S.C. 1114, and a claim of

unfair competition under 15 U.S.C. 1125. Compl. 19-27, 35-42. Claims under both these

sections are analyzed under a familiar two-pronged test: (1) whether the mark is valid and entitled

to protection; and (2) whether there is a likelihood of consumer confusion as to origin or

sponsorship of the defendants services. See Virgin Enters. Ltd. v. Nawab, 335 F.3d 141, 146 (2d

Cir. 2003).

Defendant argues that even if the mark is protectable and therefore satisfies the first prong,

Plaintiff cannot prove a likelihood of confusion. Mem. at 7.

In analyzing the second prong of the test for trademark infringement, courts apply the non-

exclusive multi-factor test developed in Polaroid Corp. v. Polarad Elecs. Corp., 287 F.2d 492, 495

(2d Cir. 1961), and consider: (1) the strength of the mark, (2) the similarity of the two marks, (3) the

proximity of the products, (4) actual confusion, (5) the likelihood of plaintiffs bridging the gap, (6)

defendants good faith in adopting the mark, (7) the quality of defendants products, and (8) the

sophistication of the consumers. Louis Vuitton Malletier v. Dooney & Bourke, Inc., 454 F.3d 108,

116 (2d Cir. 2006).

2

1. Strength of the Mark

The first Polaroid factor measures a marks tendency to identify the goods [or services] sold

under the mark as emanating from a particular . . . source. The Sports Auth., Inc. v. Prime

Notably, despite Defendants analysis of each Polaroid factor in its Memorandum, Plaintiff

2

failed to discussor even citethe Polaroid factors in its Response. Mem. at 8-21; Resp.

7

Hospitality Corp., 89 F.3d 955, 960 (2d Cir. 1996). When determining a marks strength, courts

consider both the marks inherent distinctiveness, based on the characteristics of the mark itself, and

its acquired distinctiveness, based on associations the mark has gained through use in commerce.

See Streetwise Maps, Inc. v. VanDam, Inc., 159 F.3d 739, 743-44 (2d Cir. 1998). Inherent

distinctiveness examines a marks theoretical potential to identify plaintiffs goods or services

without regard to whether it has actually done so. Brennans, Inc. v. Brennans Rest., L.L.C., 360

F.3d 125, 131 (2d Cir. 2004). Acquired distinctiveness measures the recognition plaintiffs mark

has earned in the marketplace as a designator of plaintiffs goods or services. Id.

Courts classify a mark in one of four categories in increasing order of inherent

distinctiveness: generic, descriptive, suggestive, and arbitrary. Streetwise Maps, 159 F.3d at 744

(citing Abercrombie & Fitch Co. v. Hunting World, Inc., 537 F.2d 4, 9 (2d Cir. 1976)). A generic

term is a common name, like automobile or aspirin, that describes a kind of product. Gruner Jahr

USA Pub. v. Meredith Corp., 991 F.2d 1072, 1075 (2d Cir. 1993). Such terms are not entitled to

trademark protection. Id. Arbitrary marks, such as Ivory for soap, lie at the opposite end of the

spectrum. Id. at 1075-76. They are not common names for a product, and are always entitled to

trademark protection. Id.

A suggestive mark . . . suggests the product, though it may take imagination to grasp the

nature of the product. Id. at 1076. For example, the name Orange Crush suggests an orange-

flavored beverage. Id. A descriptive mark tells something about a product, its qualities,

ingredients or characteristics. Id.

The Asserted Mark is, at most, a suggestive mark, as it evokes the nostalgia for baseball

history, and Plaintiff sells baseball memorabilia. In the absence of any showing of secondary

8

meaning, suggestive marks are at best moderately strong. Star Indus., Inc. v. Bacardi & Co., 412

F.3d 373, 385 (2d Cir. 2005). Secondary meaning attaches when the name and the business have

become synonymous in the mind of the public, submerging the primary meaning of the term in favor

of its meaning as a word identifying that business. Time, Inc. v. Petersen Publg Co. L.L.C., 173

F.3d 113, 117 (2d Cir. 1999) (internal quotation marks omitted).

Courts within the Second Circuit look at six factors to establish whether a mark has acquired

secondary meaning: (1) advertising expenditures, (2) consumer studies linking the mark to a

source, (3) unsolicited media coverage of the product, (4) sales success, (5) attempts to plagiarize

the mark, and (6) length and exclusivity of the marks use. Marshall v. Marshall, No. 08-CV-1420,

2012 WL 1079550, at *16 (E.D.N.Y. Mar. 30, 2012). However, [n]o precise guidelines are

applicable and no single factor is determinative, Murphy v. Provident Mut. Life Ins. Co. of

Philadelphia, 923 F.2d 923, 928 (2d Cir. 1990) (internal quotation marks omitted), and the Second

Circuit has emphasized that the fundamental question . . . is whether the primary significance of

the term in the minds of the consuming public is not the product but the producer, Bristol-Myers

Squibb Co. v. McNeil-P.P.C., Inc., 973 F.2d 1033, 1041 (2d Cir. 1992) (quoting Centaur

Commcns, Ltd. v. A/S/M/ Commcn, Inc., 830 F.2d 1217, 1221 (2d Cir. 1987)). Whether a mark

has acquired secondary meaning is a factual determination, proof of which entails vigorous

evidentiary requirements, Marshall, 2012 WL 1079550, at *16 (internal quotation marks omitted),

and the burden of proof rests on the party asserting rights in the mark, Hi-Tech Pharmacal Co. v.

Hi-Tech Pharms., Inc., No. 05-CV-2674, 2007 WL 1988737, at *10 (E.D.N.Y. July 5, 2007).

Here, Plaintiff has produced no evidence, or even argument, to show that its Asserted Mark

has acquired secondary meaning. Accordingly, Plaintiffs Asserted Mark lacks secondary meaning

9

and is a relatively weak suggestive mark.

2. Similarity

The similarity of the marks is a key factor in determining likelihood of confusion. Louis

Vuitton Malletier, 454 F.3d at 117. To apply this factor, courts must analyze the marks overall

impression on a consumer, considering the context in which the marks are displayed and the

totality of factors that could cause confusion among prospective purchasers. Malletier v.

Burlington Coat Factory Warehouse Corp., 426 F.3d 532, 537 (2d Cir. 2005) (quoting Meredith

Corp., 991 F.2d at 1078). [T]he Lanham Act requires a court to analyze the similarity of the

products in light of the way in which the marks are actually displayed in their purchasing context.

Malletier, 426 F.3d at 538. Courts should keep in mind that in this context the law requires only

confusing similarity, not identity. Louis Vuitton, 454 F.3d at 117.

Here, the only similarities between Plaintiffs baseball shirts and the sample shirt produced

by Defendant are: (1) they are both t-shirts, and (2) they both incorporate the phrase legends are

forever. The style of the graphics on the shirts are entirely different in terms of design, color,

typeface, and theme. See SMF. Additionally, the NIKE swoosh is prominently displayed on the

allegedly infringing shirt, clearly identifying it with Defendants business, not Plaintiffs. Id. The

Accused Shirt is therefore only similar to Plaintiffs products in a superficial sense.

3. Proximity Between the Parties Goods

The proximity factor considers whether the two goods compete with each other. The Sports

Auth., 89 F.3d at 963. When the two users of a mark are operating in completely different areas of

commerce, consumers are less likely to assume that their similarly branded products come from the

same source. Virgin Enters. Ltd., 335 F.3d at 150. In contrast, the closer the secondary users

10

goods are to those the consumer has seen marketed under the prior users brand, the more likely that

the consumer will mistakenly assume a common source. Id. [D]irect competition between the

products is not a prerequisite to relief. Arrow Fastener Co. v. Stanley Works, 59 F.3d 384, 396 (2d

Cir. 1995).

The competitive proximity factor has two elements, market proximity and geographic

proximity. Brennans, 360 F.3d at 134. Market proximity asks whether the two products are in

related areas of commerce and geographic proximity looks to the geographic separation of the

products. Id. Both elements seek to determine whether the two products have an overlapping

client base that creates a potential for confusion. Id.

Here, the parties both sell sports-themed t-shirts, but Defendant is a multi-national company

that sells a range of products worldwide, while Plaintiff is a baseball memorabilia shop that sells its

goods out of a storefront in Cooperstown, NY. To the extent there is any overlap in their client

bases such that confusion might arise, it appears to be marginal. Accordingly, this factor weighs in

favor of Defendant.

4. Bridging the Gap

When two retailers do not directly compete in the same market, the bridge the gap factor

considers the likelihood that the plaintiff would enter the defendants market. See Sports Auth., 89

F.3d at 963. Here, there is no evidence that Plaintiff will expand its business to include celebrity-

themed basketball shoes and apparel like the Kobe Bryant line at issue, nor is there evidence that

Plaintiff is seeking to grow its business to compete for Defendants large consumer base. This

factor therefore weighs in favor of Defendant.

11

5. Actual Confusion

For purposes of the Lanham Act, actual confusion means consumer confusion that enables

a seller to pass off his goods as the goods of another. Sports Auth., 89 F.3d at 963 (internal

quotation marks omitted). Evidence of actual confusion is a strong indication that a likelihood of

confusion exists. However, since actual confusion is difficult to prove, it is well-established that

actual confusion need not be shown to prove likelihood of confusion under the Lanham Act. Coach

Leatherware Co. v. AnnTaylor, Inc., 933 F.2d 162, 170-71 (2d Cir. 1991) Courts can properly take

into account evidence of either a diversion of sales, damage to goodwill, or loss of control over

reputation. Morningside Grp. Ltd. v. Morningside Capital Grp., L.L.C., 182 F.3d 133, 141 (2d

Cir. 1999) (quoting Sports Auth., 89 F.3d at 963).

Typically, an infringement plaintiff undertakes to prove actual confusion between its

products and the defendants in two ways: anecdotal evidence of particular incidents and market

research surveys. Home Shopping Club, Inc. v. Charles of the Ritz Grp., Inc., 820 F. Supp. 763,

774 (S.D.N.Y. 1993). Here, Plaintiff offers neither. Instead, Plaintiff offers only the anecdote that

one customer entered its store wearing a shirt that said either legends are forever or legends live

forvever, and informed Matt Foster that it was a Kobe Bryant shirt. SMF 70. If anything, the

exchange demonstrates the customers lack of confusion. See Nora Beverages, Inc. v. Perrier Grp.

of Am., Inc., 269 F.3d 114, 124 (2d Cir. 2001) (stating that inquiries about the relationship between

an owner of a mark and an alleged infringer are arguably premised upon a lack of confusion

between the products such as to inspire the inquiry itself). This factor therefore weighs in favor of

Defendant.

12

6. Defendants Good Faith

This factor concerns whether the defendant adopted its mark with the intention of

capitalizing on plaintiffs reputation and goodwill, and any confusion between his and the senior

users product. Lang v. Ret. Living Pub. Co., 949 F.2d 576, 583 (2d Cir. 1991). Here, Plaintiff has

produced no evidence that Defendant intended to capitalize off Plaintiffs reputation. Indeed, it is

inconceivable that a rational factfinder could conclude that NIKE designed a Kobe Bryant-

sponsored t-shirt in order to sow confusion between its product and that of a baseball memorabilia

store in Cooperstown, NY. Accordingly, this factor weighs in favor of Defendant.

7. Quality of Services

This factor is primarily concerned with whether the senior users reputation could be

jeopardized by virtue of the fact that the junior users product is of inferior quality. Arrow Fastener

Co., 59 F.3d at 398. The concern is not so much with the likelihood of confusion as with the

likelihood of harm resulting from any such confusion. MGM-Pathe Commcns Co. v. Pink

Panther Patrol, 774 F. Supp. 869, 876 (S.D.N.Y. 1991); see also Virgin Enters. Ltd., 335 F.3d at

152.

Defendants products are famous and sold worldwide. SMF 51-53. Plaintiff has

presented no evidence to show that its own t-shirts are of higher quality than those sold by

Defendant. Accordingly, this factor weighs in favor of Defendant.

8. Sophistication of Customers

A high degree of consumer sophistication decreases the risk of consumer confusion.

Morningside Grp. Ltd., 182 F.3d at 142. [The] analysis of consumer sophistication consider[s] the

general impression of the ordinary purchaser, buying under the normally prevalent conditions of the

13

market and giving the attention such purchasers usually give in buying that class of goods. Star

Indus., 412 F.3d at 390 (quoting Sports Auth., 89 F.3d at 965). The level of sophistication, or lack

thereof, can be proven either by direct evidence, such as with a survey or expert opinion, or the

Court may rely on indirect indications of sophistication established by the nature of the product or

its price. 24 Hour Fitness USA, Inc. v. 24/7 Tribeca Fitness, LLC, 447 F. Supp. 2d 266, 286

(S.D.N.Y. 2006) (internal quotation marks and citations omitted).

Plaintiff has not presented any evidence to show that its customers are so unsophisticated

that they would confuse one of Defendants shirts with one of Plaintiffs. On the contrary, Plaintiff

indicates that its customers are primarily baseball fans, and in the one anecdotal case of a customer

wearing one of Defendants t-shirts in Plaintiffs store, the customer appeared well aware of the

distinction between the two. This factor therefore weighs in favor of Defendant.

9. Totality of the Polaroid Factors

Nearly all of the factors weigh heavily in favor of Defendant, and none weigh heavily in

favor of Plaintiff. Accordingly, no likelihood of confusion exists, and Defendant is entitled to

summary judgment on Plaintiffs federal trademark infringement and unfair competition claims.

B. State Common Law Claims

The elements necessary to prevail on causes of action for trademark infringement and

unfair competition under New York common law mirror analogous federal claims. ESPN, Inc. v.

Quiksilver, Inc., 586 F. Supp. 2d 219, 230 (S.D.N.Y. 2008). Accordingly, because Plaintiffs

federal trademark infringement and unfair competition claims fail as a matter of law, Defendant is

entitled to summary judgment on the analogous state law claims, as well.

14

C. Trademark Dilution Claim

A threshold question in a federal dilution claim is whether the mark at issue is famous.

Coach Servs., Inc. v. Triumph Learning LLC, 668 F.3d 1356, 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2012). A mark is

famous if it is widely recognized by the general consuming public of the United States as a

designation of source of the goods or services of the marks owner. 15 U.S.C. 1125(c)(2)(A).

Nothing in the record suggests that Plaintiffs Asserted Mark meets this exceedingly high standard.

Accordingly, Defendant is entitled to summary judgment on Plaintiffs federal trademark dilution

claim.

D. New York General Business Law 349 Claim

New York General Business Law 349(a) bars [d]eceptive acts or practices in the conduct

of any business, trade or commerce or in the furnishing of any service in New York. While

competing businesses have standing to sue under this provision, it is, at its core, a consumer

protection device, and thus the gravamen of the complaint must be consumer injury or harm to the

public interest, not mere competitive disadvantage. Mobileye, Inc. v. Picitup Corp., 928 F. Supp.

2d 759, 783 (S.D.N.Y. 2013) (quoting Securitron Magnalock Corp. v. Schnabolk, 65 F.3d 256, 264

(2d Cir. 1995)). Accordingly, it is well-established that trademark infringement actions alleging

only general consumer confusion do not threaten direct harm to consumers for purposes of stating a

claim under section 349. Luv N Care, Ltd. v. Walgreen, Co., 695 F. Supp. 2d 125, 136 (S.D.N.Y.

2010) (alteration and internal quotation marks omitted). Rather, for the statute to apply, a plaintiff

must establish a direct harm to consumers that is greater than the general consumer confusion

commonly found in trademark actions, such as potential danger to the public health or safety.

Eliya, Inc. v. Kohls Dept. Stores, 82 U.S.P.Q.2d 1088, 1096 (S.D.N.Y. 2006) (alteration and

15

internal quotations omitted).

Here, Plaintiffs claim fails as a matter of law both because of the lack of evidence to

support its infringement claims, and because of Plaintiffs failure to even allege an additional direct

harm to the public interest. See Compl. Accordingly, Defendant is entitled to summary judgment

on this claim, as well.

E. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56(d)

In its Response to Defendants Motion, Plaintiff cites Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56(d)

and requests that the Court allow additional time for Plaintiff to obtain discovery. Resp.

Under Rule 56(d), [i]f a nonmovant shows by affidavit or declaration that, for specified

reasons, it cannot present facts essential to justify its opposition, the court may: (1) defer

considering the motion or deny it; (2) allow time to obtain affidavits or declarations or to take

discovery; or (3) issue any other appropriate order. FED. R. CIV. P. 56(d). The Second Circuit has

held that a party invoking Rule 56(d) must file an affidavit that demonstrates:

(1) the nature of the uncompleted discovery, i.e., what facts are sought and how they are

to be obtained; and

(2) how those facts are reasonably expected to create a genuine issue of material fact;

and

(3) what efforts the affiant has made to obtain those facts; and

(4) why those efforts were unsuccessful.

Burlington Coat Factory Warehouse Corp. v. Esprit de Corp., 769 F.2d 919, 926 (2d Cir. 1985).

Even when a Rule 56(d) motion satisfies these requirements, a district court may refuse a partys

request for additional discovery if the party has had ample time in which to pursue the discovery

that it now claims is essential. Id. at 927; see also Trebor Sportswear Co. v. The Limited Stores,

16

Inc., 865 F.2d 506, 511 (2d Cir. 1989) (denying request for additional discovery when the party

opposing summary judgment had a fully adequate opportunity for discovery).

Here, Plaintiff states that it failed to obtain an expert report due to financial difficulties

imposed by other litigation. Resp. at 1; Dkt. No. 36-1. However, Plaintiffs lack of diligence in

conducting discovery in this case is well documented in the record. See, e.g., Fees Order; Dkt. Nos.

15; 45. Furthermore, the litigation that allegedly prevented Plaintiff from hiring an expert arose in

2012, meaning that Plaintiff could have requested an extension of the discovery deadline in this

case. See Dkt. No. 36-1 23-26. Plaintiff did not do so. See Docket. Accordingly, because

Plaintiff failed to take advantage of the ample opportunity afforded it to obtain an expert report, the

Court rejects its Rule 56(d) request.

V. CONCLUSION

Accordingly, it is hereby:

ORDERED, that Defendants Motion (Dkt. No. 30) for summary judgment is GRANTED;

and it is further

ORDERED, that the Clerk of the Court enter judgment for Defendant and close this case;

and it is further

ORDERED, that the Clerk of the Court serve a copy of this Memorandum-Decision and

Order on all parties in accordance with the Local Rules.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

DATED: September 30, 2014

Albany, NY

17

You might also like

- 7 - Lakhs Bank EstimateDocument8 pages7 - Lakhs Bank Estimatevikram Bargur67% (3)

- Cape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyFrom EverandCape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyNo ratings yet

- PopSockets v. DozTrading - ComplaintDocument106 pagesPopSockets v. DozTrading - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- HobbitsDocument32 pagesHobbitseriqgardnerNo ratings yet

- Olaes Enters. v. Walking T Bear - ComplaintDocument9 pagesOlaes Enters. v. Walking T Bear - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Atari v. NestleDocument39 pagesAtari v. NestleTHROnlineNo ratings yet

- Nevada Reply BriefDocument36 pagesNevada Reply BriefBasseemNo ratings yet

- Zaranda Finlay 684 Manual Parts CatalogDocument405 pagesZaranda Finlay 684 Manual Parts CatalogRicky Vil100% (2)

- PS Prods. v. Activision - MTD OppositionDocument20 pagesPS Prods. v. Activision - MTD OppositionSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- P.S. Prods. v. Activision Blizzard - MTD ResponseDocument13 pagesP.S. Prods. v. Activision Blizzard - MTD ResponseSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Fun World V Terry RozierDocument12 pagesFun World V Terry RozierDarren Adam HeitnerNo ratings yet

- Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, Inc. v. Pussycat Cinema, Ltd. and Michael Zaffarano, 604 F.2d 200, 2d Cir. (1979)Document9 pagesDallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, Inc. v. Pussycat Cinema, Ltd. and Michael Zaffarano, 604 F.2d 200, 2d Cir. (1979)Scribd Government Docs0% (1)

- Scott Paper Company, A Corporation v. Scott's Liquid Gold, Inc., A Corporation, 589 F.2d 1225, 3rd Cir. (1978)Document9 pagesScott Paper Company, A Corporation v. Scott's Liquid Gold, Inc., A Corporation, 589 F.2d 1225, 3rd Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Hunter Moore Brandi Passante JudgmentDocument8 pagesHunter Moore Brandi Passante JudgmentAdam SteinbaughNo ratings yet

- Crorey Creations v. Hobby Lobby StoresDocument6 pagesCrorey Creations v. Hobby Lobby StoresPatent LitigationNo ratings yet

- Jane Envy v. Infinite Classic - Jewelry Copyright Summary Judgment PDFDocument45 pagesJane Envy v. Infinite Classic - Jewelry Copyright Summary Judgment PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Complaint PhilbrickDocument66 pagesComplaint Philbrickmschwimmer100% (1)

- Polo Fashions, Inc. v. Craftex, Inc., and Bobby O'Neal and Keith O'neal, Polo Fashions, Inc. v. Craftex, Inc. Bobby O'Neal and Keith O'Neal, 816 F.2d 145, 4th Cir. (1987)Document6 pagesPolo Fashions, Inc. v. Craftex, Inc., and Bobby O'Neal and Keith O'neal, Polo Fashions, Inc. v. Craftex, Inc. Bobby O'Neal and Keith O'Neal, 816 F.2d 145, 4th Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., LTD., Nintendo of America, Inc., 746 F.2d 112, 2d Cir. (1984)Document11 pagesUniversal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., LTD., Nintendo of America, Inc., 746 F.2d 112, 2d Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Hyde Park Clothes, Inc. v. Hyde Park Fashions, Inc, 204 F.2d 223, 2d Cir. (1953)Document10 pagesHyde Park Clothes, Inc. v. Hyde Park Fashions, Inc, 204 F.2d 223, 2d Cir. (1953)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Report and RecomendationsDocument31 pagesReport and RecomendationsMMA PayoutNo ratings yet

- K&M v. NDY Toy - Attorney Eyes Only Opinion PDFDocument11 pagesK&M v. NDY Toy - Attorney Eyes Only Opinion PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- L.A. Triumph v. Madonna (C.D. Cal. 2011) (Order Denying Motion For Summary Judgment)Document7 pagesL.A. Triumph v. Madonna (C.D. Cal. 2011) (Order Denying Motion For Summary Judgment)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Schmidt v. SGBX Global - ComplaintDocument17 pagesSchmidt v. SGBX Global - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Kiki Undies Corporation v. Alexander's Department Stores, Inc., 390 F.2d 604, 2d Cir. (1968)Document3 pagesKiki Undies Corporation v. Alexander's Department Stores, Inc., 390 F.2d 604, 2d Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cram v. The Fanatic Group - ComplaintDocument44 pagesCram v. The Fanatic Group - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Sidney J. Friedman, D.B.A. Wyandotte Mattress Company v. Sealy, Incorporated, 274 F.2d 255, 10th Cir. (1960)Document11 pagesSidney J. Friedman, D.B.A. Wyandotte Mattress Company v. Sealy, Incorporated, 274 F.2d 255, 10th Cir. (1960)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- LIP DigestDocument46 pagesLIP DigestLottyiggyNo ratings yet

- High 5 Games v. Gimme Games - Video Game Trade Secrets PDFDocument18 pagesHigh 5 Games v. Gimme Games - Video Game Trade Secrets PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Kuper v. Reid - PANCAKE MAN Trademark Opinion PDFDocument11 pagesKuper v. Reid - PANCAKE MAN Trademark Opinion PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Fisher Stoves, Inc. v. All Nighter Stove Works, Inc., 626 F.2d 193, 1st Cir. (1980)Document5 pagesFisher Stoves, Inc. v. All Nighter Stove Works, Inc., 626 F.2d 193, 1st Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pro-Troll v. KDMA - Order Granting SJDocument20 pagesPro-Troll v. KDMA - Order Granting SJSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Crorey Creations v. TargetDocument5 pagesCrorey Creations v. TargetPriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Interpace Corporation v. Lapp, Inc., 721 F.2d 460, 3rd Cir. (1983)Document6 pagesInterpace Corporation v. Lapp, Inc., 721 F.2d 460, 3rd Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals For The Federal CircuitDocument15 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals For The Federal CircuitpauloverhauserNo ratings yet

- Celebrity, Inc., A Corporation v. A & B Instrument Company, Inc., A Corporation, and Mid-America Sales and Marketing, Inc., A Corporation, 573 F.2d 11, 10th Cir. (1978)Document6 pagesCelebrity, Inc., A Corporation v. A & B Instrument Company, Inc., A Corporation, and Mid-America Sales and Marketing, Inc., A Corporation, 573 F.2d 11, 10th Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Hayden V 2K Games MTD OrderDocument12 pagesHayden V 2K Games MTD OrderTHROnlineNo ratings yet

- Skell v. Dillards - ComplaintDocument99 pagesSkell v. Dillards - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Mushroom Makers, Incorporated v. R. G. Barry Corporation, 580 F.2d 44, 2d Cir. (1978)Document7 pagesMushroom Makers, Incorporated v. R. G. Barry Corporation, 580 F.2d 44, 2d Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pride Mfg. v. Evolve Golf - ComplaintDocument20 pagesPride Mfg. v. Evolve Golf - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Thomas Wilson & Company, Inc. v. Irving J. Dorfman Company, Inc., 433 F.2d 409, 2d Cir. (1970)Document8 pagesThomas Wilson & Company, Inc. v. Irving J. Dorfman Company, Inc., 433 F.2d 409, 2d Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 605 F.2d 110 56 A.L.R.Fed. 649, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. P 97,110: United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument9 pages605 F.2d 110 56 A.L.R.Fed. 649, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. P 97,110: United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Deckers v. Does, 11-Cv-7970 (N.D. Ill. Dec. 14, 2011) (R& R)Document61 pagesDeckers v. Does, 11-Cv-7970 (N.D. Ill. Dec. 14, 2011) (R& R)Venkat BalasubramaniNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Injunction Order - Lego v. Zuru (D. Conn. 2018)Document46 pagesPreliminary Injunction Order - Lego v. Zuru (D. Conn. 2018)Darius C. GambinoNo ratings yet

- Wal-Mart v. Samara Brothers DecisionDocument10 pagesWal-Mart v. Samara Brothers DecisionThe Fashion LawNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Sixth CircuitDocument10 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Sixth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- BogartDocument43 pagesBogarteriqgardnerNo ratings yet

- International Silver Co. v. Julie Pomerantz, 271 F.2d 69, 2d Cir. (1959)Document5 pagesInternational Silver Co. v. Julie Pomerantz, 271 F.2d 69, 2d Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Blisscraft of Hollywood v. United Plastics Company, Marmax Products Corp., and Morris Shapiro, Doing Business As Great Eastern Housewares Company, 294 F.2d 694, 2d Cir. (1961)Document12 pagesBlisscraft of Hollywood v. United Plastics Company, Marmax Products Corp., and Morris Shapiro, Doing Business As Great Eastern Housewares Company, 294 F.2d 694, 2d Cir. (1961)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Alper Automotive v. Day To Day Imports - Order Granting Summary JudgmentDocument10 pagesAlper Automotive v. Day To Day Imports - Order Granting Summary JudgmentSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Riback Enterprises, Inc. v. George Denham, 452 F.2d 845, 2d Cir. (1971)Document5 pagesRiback Enterprises, Inc. v. George Denham, 452 F.2d 845, 2d Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Smash v. LB InternationalDocument5 pagesSmash v. LB InternationalPriorSmartNo ratings yet

- CAESARS WORLD, INC. and Desert Palace, Inc., Appellants in No. 74-1725, v. VENUS LOUNGE, INC., D/b/a Caesar's Palace, Appellant in No. 74-1724Document8 pagesCAESARS WORLD, INC. and Desert Palace, Inc., Appellants in No. 74-1725, v. VENUS LOUNGE, INC., D/b/a Caesar's Palace, Appellant in No. 74-1724Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Handy Twine Knife v. Continental Western - ComplaintDocument168 pagesHandy Twine Knife v. Continental Western - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Black & Decker v. Positec - ComplaintDocument11 pagesBlack & Decker v. Positec - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Malibu Media v. Waller - Vacate Default PDFDocument9 pagesMalibu Media v. Waller - Vacate Default PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- G.I. Sportz Direct v. Virtue Paintball - ComplaintDocument203 pagesG.I. Sportz Direct v. Virtue Paintball - ComplaintSarah Burstein0% (1)

- Knickerbocker Plastic Co., Inc. v. Allied Molding Corp. Knickerbocker Plastic Co., Inc. v. B. Shackman & Co., Inc, 184 F.2d 652, 2d Cir. (1950)Document4 pagesKnickerbocker Plastic Co., Inc. v. Allied Molding Corp. Knickerbocker Plastic Co., Inc. v. B. Shackman & Co., Inc, 184 F.2d 652, 2d Cir. (1950)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Under The Weather v. Christmas Tree Shops - ComplaintDocument75 pagesUnder The Weather v. Christmas Tree Shops - ComplaintSarah Burstein100% (1)

- Decision Famous Horse V 5thDocument36 pagesDecision Famous Horse V 5thmschwimmerNo ratings yet

- Virtual Reality Feedback Et. Al. v. Target Brands Et. Al.Document9 pagesVirtual Reality Feedback Et. Al. v. Target Brands Et. Al.PriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Samtech v. Brooklyn Armed Forces - ComplaintDocument32 pagesSamtech v. Brooklyn Armed Forces - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Petition for Certiorari: Denied Without Opinion Patent Case 93-1413From EverandPetition for Certiorari: Denied Without Opinion Patent Case 93-1413No ratings yet

- Soundgarden v. UMG - UMG Motion To DismissDocument34 pagesSoundgarden v. UMG - UMG Motion To DismissMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Bobby Coldwell/Lil Nas X Complaint - Music Force v. Sony Music, Lil Nas X, WynterbeatsDocument7 pagesBobby Coldwell/Lil Nas X Complaint - Music Force v. Sony Music, Lil Nas X, WynterbeatsMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Capital Records Letter Response To Termination Notice - Waite v. UMGDocument7 pagesCapital Records Letter Response To Termination Notice - Waite v. UMGMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Lil Nas X Complaint - Exhibit ADocument5 pagesLil Nas X Complaint - Exhibit AMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Crowdfunding Final Rules Issued 10-30-2015Document686 pagesCrowdfunding Final Rules Issued 10-30-2015Divina WesterfieldNo ratings yet

- Hiq v. LinkedInDocument25 pagesHiq v. LinkedInBennet KelleyNo ratings yet

- Us V Trump Case Via National Archives FoiaDocument1,019 pagesUs V Trump Case Via National Archives FoiaMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Trump Management Company Part 01 of 01Document389 pagesTrump Management Company Part 01 of 01Mark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Subway Footlong 7th Circuit Class ActionDocument11 pagesSubway Footlong 7th Circuit Class ActionMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- SEC Crowdfunding Rules Nov. 16, 2015Document229 pagesSEC Crowdfunding Rules Nov. 16, 2015Mark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Moonin v. Tice 15-16571 First Amendment K9Document38 pagesMoonin v. Tice 15-16571 First Amendment K9Mark JaffeNo ratings yet

- O Connor v. Uber Order Denying Plaintiffs Mot For Preliminary ADocument35 pagesO Connor v. Uber Order Denying Plaintiffs Mot For Preliminary AMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Ernst Young v. Murphy - Susan Fowler Amicus BriefDocument18 pagesErnst Young v. Murphy - Susan Fowler Amicus BriefMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Block v. Tanenhaus - Slavery Wasnt So Bad DefamationDocument11 pagesBlock v. Tanenhaus - Slavery Wasnt So Bad DefamationMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Centro de La Comunidad v. Oyster Bay - 2nd Circuit First Amendment OpinionDocument42 pagesCentro de La Comunidad v. Oyster Bay - 2nd Circuit First Amendment OpinionMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Mackenzie Architects v. VLG Real Estate, Et Al. - Order On Motion On The PleadingsDocument30 pagesMackenzie Architects v. VLG Real Estate, Et Al. - Order On Motion On The PleadingsMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Bowman v. Indiana - Dog SearchDocument8 pagesBowman v. Indiana - Dog SearchMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Tierney Pka Rime v. Camuto ComplaintDocument11 pagesTierney Pka Rime v. Camuto ComplaintMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- SEC V Drake - ComplaintDocument15 pagesSEC V Drake - ComplaintMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- ARPAIO Lawyers MOTION For A NEW TRIAL Arpaio Adv. USA MTN For A New Trial or To Vacate The VerdictDocument17 pagesARPAIO Lawyers MOTION For A NEW TRIAL Arpaio Adv. USA MTN For A New Trial or To Vacate The VerdictJerome CorsiNo ratings yet

- US v. Lostutter - Mark Jaffe Admission Pro Hac ViceDocument1 pageUS v. Lostutter - Mark Jaffe Admission Pro Hac ViceMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- CFPB Enforcement Action (Wells Fargo)Document26 pagesCFPB Enforcement Action (Wells Fargo)United Press International100% (1)

- Arpaio Criminal Contempt VerdictDocument14 pagesArpaio Criminal Contempt Verdictpaul weichNo ratings yet

- Paisley Park v. Boxill - Motion To Seal DocumentDocument3 pagesPaisley Park v. Boxill - Motion To Seal DocumentMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Horror Inc. v. Miller - Friday The 13th Complaint PDFDocument17 pagesHorror Inc. v. Miller - Friday The 13th Complaint PDFMark Jaffe100% (1)

- Paisley Park v. Boxill - Notice of RemovalDocument4 pagesPaisley Park v. Boxill - Notice of RemovalMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Slated IP v. Independent Film Dev Group - Sup CT NY Opinion PDFDocument34 pagesSlated IP v. Independent Film Dev Group - Sup CT NY Opinion PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Griffin v. Ed Sheeran - Lets Get It On Copyright Complaint PDFDocument19 pagesGriffin v. Ed Sheeran - Lets Get It On Copyright Complaint PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Indictment USA V Lostutter Aka KYAnonymous PDFDocument9 pagesIndictment USA V Lostutter Aka KYAnonymous PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Aggregate Demand and Supply: A ReviewDocument36 pagesAggregate Demand and Supply: A ReviewYovan DharmawanNo ratings yet

- MongoDB vs RDBMS - A ComparisonDocument20 pagesMongoDB vs RDBMS - A ComparisonShashank GuptaNo ratings yet

- InfosysDocument22 pagesInfosysTarun Singhal50% (2)

- LogDocument85 pagesLogJo NasNo ratings yet

- JAM 2020 Information Brochure: Admission to M.Sc., Joint M.Sc.-Ph.D., M.Sc.-Ph.D. Dual Degree and Integrated Ph.D. ProgrammesDocument51 pagesJAM 2020 Information Brochure: Admission to M.Sc., Joint M.Sc.-Ph.D., M.Sc.-Ph.D. Dual Degree and Integrated Ph.D. ProgrammesVaibhav PachauleeNo ratings yet

- Private Car Package Policy - Zone B Motor Insurance Certificate Cum Policy ScheduleDocument3 pagesPrivate Car Package Policy - Zone B Motor Insurance Certificate Cum Policy ScheduleijustyadavNo ratings yet

- 028 Ptrs Modul Matematik t4 Sel-96-99Document4 pages028 Ptrs Modul Matematik t4 Sel-96-99mardhiah88No ratings yet

- DMT80600L104 21WTR Datasheet DATASHEETDocument3 pagesDMT80600L104 21WTR Datasheet DATASHEETtnenNo ratings yet

- Kj1010-6804-Man604-Man205 - Chapter 7Document16 pagesKj1010-6804-Man604-Man205 - Chapter 7ghalibNo ratings yet

- MTD Microwave Techniques and Devices TEXTDocument551 pagesMTD Microwave Techniques and Devices TEXTARAVINDNo ratings yet

- Common Size Statement: A Technique of Financial Analysis: June 2019Document8 pagesCommon Size Statement: A Technique of Financial Analysis: June 2019safa haddadNo ratings yet

- TN1Ue Reference Manual Issue 9.0Document144 pagesTN1Ue Reference Manual Issue 9.0Reinaldo Sciliano juniorNo ratings yet

- Timesheet 2021Document1 pageTimesheet 20212ys2njx57vNo ratings yet

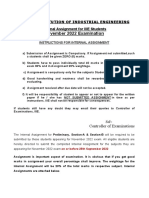

- November 2022 Examination: Indian Institution of Industrial Engineering Internal Assignment For IIIE StudentsDocument19 pagesNovember 2022 Examination: Indian Institution of Industrial Engineering Internal Assignment For IIIE Studentssatish gordeNo ratings yet

- Computer Application in Business NOTES PDFDocument78 pagesComputer Application in Business NOTES PDFGhulam Sarwar SoomroNo ratings yet

- Depressurization LED Solar Charge Controller with Constant Current Source SR-DL100/SR-DL50Document4 pagesDepressurization LED Solar Charge Controller with Constant Current Source SR-DL100/SR-DL50Ria IndahNo ratings yet

- Social Vulnerability Index Helps Emergency ManagementDocument24 pagesSocial Vulnerability Index Helps Emergency ManagementDeden IstiawanNo ratings yet

- Cache Memory in Computer Architecture - Gate VidyalayDocument6 pagesCache Memory in Computer Architecture - Gate VidyalayPAINNo ratings yet

- Duplex Color Image Reader Unit C1 SMDocument152 pagesDuplex Color Image Reader Unit C1 SMWatcharapon WiwutNo ratings yet

- How To Google Like A Pro-10 Tips For More Effective GooglingDocument10 pagesHow To Google Like A Pro-10 Tips For More Effective GooglingMinh Dang HoangNo ratings yet

- Basic Concept of EntrepreneurshipDocument12 pagesBasic Concept of EntrepreneurshipMaria January B. FedericoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 122039 May 31, 2000 VICENTE CALALAS, Petitioner, Court of Appeals, Eliza Jujeurche Sunga and Francisco Salva, RespondentsDocument56 pagesG.R. No. 122039 May 31, 2000 VICENTE CALALAS, Petitioner, Court of Appeals, Eliza Jujeurche Sunga and Francisco Salva, RespondentsJayson AbabaNo ratings yet

- ID Analisis Persetujuan Tindakan Kedokteran Informed Consent Dalam Rangka Persiapan PDFDocument11 pagesID Analisis Persetujuan Tindakan Kedokteran Informed Consent Dalam Rangka Persiapan PDFAmelia AmelNo ratings yet

- Design of A Double Corbel Using CAST Per ACI 318-02 Appendix A, SI UnitDocument41 pagesDesign of A Double Corbel Using CAST Per ACI 318-02 Appendix A, SI Unityoga arkanNo ratings yet

- Naoh Storage Tank Design Description:: Calculations For Tank VolumeDocument6 pagesNaoh Storage Tank Design Description:: Calculations For Tank VolumeMaria Eloisa Angelie ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Investigations in Environmental Science: A Case-Based Approach To The Study of Environmental Systems (Cases)Document16 pagesInvestigations in Environmental Science: A Case-Based Approach To The Study of Environmental Systems (Cases)geodeNo ratings yet

- Baylan: VK-6 Volumetric Water MeterDocument1 pageBaylan: VK-6 Volumetric Water MeterSanjeewa ChathurangaNo ratings yet