Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Saer, With Breakfast

Uploaded by

Casey GoughCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Saer, With Breakfast

Uploaded by

Casey GoughCopyright:

Available Formats

1

With Breakfast

Goldstein was 21 in 1943, when he was deported to a

concentration camp for the triple motive of being Jewish,

Communist, and a member of the Resistance. He was not

killed, for it is common knowledge that the Nazi camps were, in

theory, labor camps, and the Germans hoped to win the war

thanks to the efforts of their more robust enemies. Useless

peoplechildren, the sick, the elderlywere murdered

immediately, but they put the young to work. In a way, thinks

Goldstein, given the manner in which they organized the

prisoners work, the Nazi camps represent an example avant la

lettre of what may well have been the final stage of the so-

called deregulation of the labor market. Consequently,

Goldstein is convinced that it was his status as cheap labor that

saved his life.

Just when the Nazis were about to have him shot for

attempting to escape, the allies arrived (they didnt find a

single German soldier in the entire camp), so that this morning,

while he eats breakfast in the Tobas caf, at the corner of

Crdoba and Pueyrredon, he is 76 years old and still goes to his

office supplies store every day, more to distract himself than

anything else, since five years ago he left the business to his

two employees, who pay him rent each month. His wife died

three years ago. His oldest daughter, who had to leave the

country after the military coup of 1976, married a Catalan and

moved to Barcelona. The younger daughter, a psychoanalyst,

has little free time during the week, and so only on occasional

nights, and occasional Sundays, do they manage to meet up for

dinner, but in any event, due to some political differences, his

relationship with her is a bit more difficult than with the older

one. Every Thursday night he has a meeting with the Human

Rights group, and every Friday, his weekly poker game.

Consequently, the daylight hours, from early morning when he

wakes up until dusk, are the most difficult to occupy.

Following the indecision of the early morning, and

preceding the interminable hours to come, the breakfast that,

as it includes the reading of the newspaper, lasts for some time,

is a moment of activity, primarily of the interior sort, since

2

now his memory and his intelligence, revived by the hours of

sleep and the lukewarm shower that relaxes his body and

tempers the little muscle and bone aches that will tug at him

for the rest of the day, can more easily concentrate and take in

images and thoughts with greater clarity. For the last twelve

years, more or less, his breakfast has been the same:

sweetened coffee with milk, orange juice, two croissants, and, a

bit later, after having read a good part of the newspaper, a shot

of espresso, dark and strong, and a glass of water. The table is

almost always the same; coming in and heading towards the

right, the last one next to the window looking out onto

Pueyrredon Avenue. Every morning, when he enters the caf,

he greets the owner, who is behind the cash register, and heads

for his spot, seating himself in the corner facing the door, right

beneath the unplugged television.

Grinning and bearing it as always this morning, don

Goldstein? says the waiter from Catamarca, depositing the

croissants and the yellow juice upon the table, without waiting

for the order, while the owner, behind the bar, has begun to

prepare the coffee. A half hour later, more or less, an almost

imperceptible gesture from Goldstein towards the register will

bring the carefully prepared espresso, accompanied by the

glass of water, to alight upon the table. For now, unfolding the

newspaper, he responds to the waiter with distracted joviality

and with the slight accent of an old Buenos Aires Jew from the

Once or Balvanera neighborhood.

What can you do, buddy? Its better than rotting away

in bed.

The fresh juice, just squeezed, sweet and tart at the same time,

gives him a little jolt of optimism when he takes the first sip,

which might just prove, since the vitamins would not yet have

had time to produce their energizing effects, that in life,

pleasure itself is a stimulant. Dipping his croissants in the

coffee, absorbing it little by little, makes it difficult to read the

newspaper, compelling him to quickly gulp down the pastries,

not out of greed, but rather because he wants to keep his hands

free in order to better handle the large sheets of printed paper

that, cumbersome and noisy, fold and unfold of their own

3

accord. At last he dominates the paper, and turns his attention

to Politics (national and international), Economy, and the Arts,

glances at the sports section and the weather report, and ends

with Entertainment. Then he goes back, and carefully reads

the letters from the readers, the editorials, and the regular

columnists, some of whom he knows personally because they

are clients of his store. From time to time he takes little sips of

juice or coffee, until hes finished, and finally, when only a few

minutes of reading remain, he signals for the espresso and the

glass of water.

This ceremony, repeated every morning for years, is

actually the preamble to the minutes of meditation that will

follow. But perhaps calling this state a meditation is

something of a poetic license, since meditation presupposes a

certain conscious will to think about particular subjects, and in

his case, there are only autonomous, associative mechanisms,

almost mechanical, which install themselves in his interior

every morning, after breakfast, and completely occupy his

attention for some time. To all appearances he is a serene and

tidy old man who dresses with simplicity and who, like so

many other inhabitants of the city, eats breakfast in a Buenos

Aires caf. On the inside, however, every morning, for several

minutes, due to that unconscious association to whose

punctual repetition he has already, after many years, resigned

himself, in an empty corner of his mind there arrives, on cue,

every massacre of the century. He counts them, and whenever

new ones appear, he adds them to the list, so that when he

evokes and enumerates them, he cannot avoid recalling the

verses of Dante:

vena si lunga tratta

di gente, chi non averei credutto

que morte tanta n'avesse disfatta.

So many people, I would not have believed that death had

undone so many: and even this multitude of ghosts did not take

into account all those who had died on the field of battle, or by

accident, or because of sickness, or killed themselves, or even

those executed for committing crimes. No: he was only

4

counting people who had been exterminated, not because they

posed any threat, real or imaginary, but rather because, for

some reason that only their murderers considered legitimate,

it was decided that a specific group of people must not live, e.g.:

for the Turks, this group was the Armenians (1,300,000), for

the Hutus it was the Tutsis (800,000), for the Nazis it was the

Jews (6,000,000), the gypsies (600,000) and the mentally

handicapped (number unknown). For the Americans, this

group was the inhabitants of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

(300,000), those who opposed Suharto in Indonesia (500,000)

or the Iraqis during the Gulf War (170,000). For Stalin, who

saw the entire Exterior as a threat, this group encompassed the

several millions of specters that, he claimed, lay in wait for him

out there. And then there were those local massacres, in which,

in a single afternoon, in a single week, various dozens or

hundreds or thousands of people died at the hands of their

executioners, who, for inexplicable reasons in which no

rational interest came into play, could not tolerate their

existence in this world: Indians, Blacks, Bosnians, Serbians,

Christians, Muslims, the elderly, women (a serial killer had

murdered close to sixty in the U.S.; all of them blonde, of a

certain weight, a certain body type , certain haircut, between

twenty and thirty years old). Truth to be told, they were all

serial killings, since, for the murderers, the victims always had

something in common, and it was only because of this that they

killed them: for the Turks, the Armenians were all Armenians

and only Armenians, and only because they were Armenians

did they exterminate them, in the same manner in which the

American serial killer murdered blondes, and only blondes,

and only because they were blondes did he kill them.

Although he considered himself an atheist and a

materialist, and often took pride in being so, Goldstein also

thought that the gods did not escape unscathed from that

carnival that paraded across his mind every morning, with

breakfast, and most of the time, whether the worshippers were

on the side of the victims or the executioners, who changed

roles many times according to the circumstances, the gods

suffered the perverse effects of these butcheries. Many of them

disappeared or, as their followers changed, they changed their

5

sign, losing their identity or their most important attributes,

revealing hidden traits that no one had ever noticed before.

They had probably fled in terror many times, which would

almost have been preferable, since the indifference with which

they had abandoned their followers was, to tell the truth,

abominable. In other instances, when the murderers invoked

them as a pretext for their massacres, it was either to distort

them or unmask them altogether: no other explanation was

possible. On the other hand, with every series that vanished

such-and-such Amazonian tribe at the hands of the big

landowners, for example lots of gods, gods who had

conceived, begat and organized the universe in order to offer it

up as a gift to mankind, were forever wiped out, together with

the universe that they had created and all the creatures that

inhabited it. And if the survivors, after what had happened to

the overwhelming majority of the series to which they

belonged, continued worshipping the gods who had permitted

such things to happen, they not only profaned the memory of

those who had disappeared, but also made themselves

ridiculous and, for the same reason, appeared ridiculous before

their gods.

Theyre better not be any eternity, and if there is, at the

very least it better not have any associations!, repeated

Goldstein to himself, during the first months in which this

unconscious and autonomous association, whose precise cause

(the first term of the association) he could not discover,

overpowered him every morning, with breakfast, and did not

abandon him until he went out into the street where, merging

with the tumult of the present, he let himself be enveloped by

the bustle of the street. Mental Association as Hell: for

Goldstein, during those first months, this expression ought to

have been the title of a major treatise. His thoughts were

agitated by the most absurd calculations, and he considered all

of those crimes not from a compassionate or ethical point of

view, but rather in terms of the quantity of victims in relation

to the extension of time of the massacres, as if it were an

algebraic formula. But this stubborn obsession, this odious

early morning theater, had endured for so many months, so

many years, that he had become accustomed to its presence, to

6

the point that the anxiety that accompanied it was exhausted,

and, resigned, one fine morning he finally understood: the

first term of the association is my life. His initial anxiety was

replaced by a strange impression that still persists, and

terminates the episode every morning: the incredible

sensation of being alive in the face of that interminable parade

of ghosts. The fact seemed improbable, fictitious, extremely

fragile, and for a fraction of a second, its very precariousness

sets the universe dancing on the edge of an abyss.

The two years he spent in the concentration camp were,

at the time, an unbearable nightmare, but soon after leaving,

Goldstein, incredible as it may seem, began thinking of them as

a positive experience in his life. His argument is the following:

at the age of 21, his vision of the world was too optimistic. If

the war had ended without him having that experience, his

optimistic prejudices would have continued to distort his

perception of reality. Crime, torture, and massacres define the

human species far more accurately than art, science, or

institutions. Before his perplexed interlocutors, Goldstein

(whom some considered rather eccentric in his opinions, if not

a little senile) affirmed that, as a man, his body and his mind

had suffered in the concentration camp, but that, as a thinker,

for him those two years represented his diploma with highest

honors in anthropology.

When he finishes the coffee and folds up the paper,

Goldstein leaves enough money on the table for the breakfast

plus tip, and, calling out a sweeping and affable See you

tomorrow!, he ventures out into the sunny street and the

rumbling intersection of the two avenues: for the passers-by,

who observe him with fleeting curiosity, he is a tidy and jovial

old man, well-preserved despite the years, probably older than

he appears, and who, judging by his energetic and satisfied air,

doesnt seem to have had it so bad in life.

Juan Jos Saer

You might also like

- Pages from an Old Volume of Life; A Collection of Essays, 1857-1881From EverandPages from an Old Volume of Life; A Collection of Essays, 1857-1881No ratings yet

- This Has Happened: An Italian Family in AuschwitzFrom EverandThis Has Happened: An Italian Family in AuschwitzRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (26)

- What They Didn't Burn: Uncovering My Father's Holocaust SecretsFrom EverandWhat They Didn't Burn: Uncovering My Father's Holocaust SecretsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Charles Dickens - Thoughts About People: "Credit is a system whereby a person who can not pay gets another person who can not pay to guarantee that he can pay."From EverandCharles Dickens - Thoughts About People: "Credit is a system whereby a person who can not pay gets another person who can not pay to guarantee that he can pay."No ratings yet

- City of Discontent: An Interpretive Biography of Rachel LindsayFrom EverandCity of Discontent: An Interpretive Biography of Rachel LindsayRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- CRIME AND PUNISHMENT: The Unabridged Garnett TranslationFrom EverandCRIME AND PUNISHMENT: The Unabridged Garnett TranslationNo ratings yet

- Rabbi Hitler,Jesus Remembers an Unauthorized and Unorthodox Life of Jesus Christ, the Secret Life of Monsignor Justin Blayne, the Girl of the ForestFrom EverandRabbi Hitler,Jesus Remembers an Unauthorized and Unorthodox Life of Jesus Christ, the Secret Life of Monsignor Justin Blayne, the Girl of the ForestNo ratings yet

- The Pleasure of Thinking: A Journey through the Sideways Leaps of IdeasFrom EverandThe Pleasure of Thinking: A Journey through the Sideways Leaps of IdeasNo ratings yet

- The Collected Essays Volume One: Occasional Prose, The Writing on the Wall, and Ideas and the NovelFrom EverandThe Collected Essays Volume One: Occasional Prose, The Writing on the Wall, and Ideas and the NovelNo ratings yet

- The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (Historical Novel)From EverandThe Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (Historical Novel)No ratings yet

- Down and Out in Paradise: The Life of Anthony BourdainFrom EverandDown and Out in Paradise: The Life of Anthony BourdainRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Notes On Chilean Literature (Or Those Queer Birds Disturbing The Necrophilic Silence of The Barrio Alto) - First of The MonthDocument16 pagesNotes On Chilean Literature (Or Those Queer Birds Disturbing The Necrophilic Silence of The Barrio Alto) - First of The MonthPaulo José CoutinhoNo ratings yet

- The OutcastDocument69 pagesThe OutcastMatthew FarrugiaNo ratings yet

- What A Long, Strange Trip It's BeenDocument5 pagesWhat A Long, Strange Trip It's BeenJustin QuinnNo ratings yet

- Book by Fyodor DostoyevskyDocument381 pagesBook by Fyodor DostoyevskyGilbert100% (1)

- What White Publishers Wont PrintDocument5 pagesWhat White Publishers Wont PrintMarcio GoldmanNo ratings yet

- Quincey, Thomas de - On Murder Considered As One of The Fine ArtsDocument9 pagesQuincey, Thomas de - On Murder Considered As One of The Fine ArtsFernando RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Nationalism in The NovelsDocument37 pagesNationalism in The NovelsSharon Servidad-MonsaleNo ratings yet

- The Summoning Smith Ebook Full ChapterDocument51 pagesThe Summoning Smith Ebook Full Chaptermay.hernandez362100% (7)

- A SKETCH OF THE NATIVE OF NORTH AMERICA by James K. Paulding (Continental Army Series)Document2 pagesA SKETCH OF THE NATIVE OF NORTH AMERICA by James K. Paulding (Continental Army Series)Wm. Thomas ShermanNo ratings yet

- "The Perils of Indifference" by Elie WieselDocument4 pages"The Perils of Indifference" by Elie Wieselapi-385441151No ratings yet

- "It's Not A Dead Language," Really, What Was The Point? There Was No UndoingDocument2 pages"It's Not A Dead Language," Really, What Was The Point? There Was No Undoingwamu885No ratings yet

- Memento MoriDocument6 pagesMemento MoriHans Lawrence MalgapuNo ratings yet

- Set Things Free: By: Jullie Ann B. AcuninDocument5 pagesSet Things Free: By: Jullie Ann B. AcuninRobert MaganaNo ratings yet

- Rigadoon - Celine, Louis-Ferdinand - 2011 - Dell Publishing - 9780440073642 - Anna's ArchiveDocument219 pagesRigadoon - Celine, Louis-Ferdinand - 2011 - Dell Publishing - 9780440073642 - Anna's ArchiveAndrei GabrielNo ratings yet

- On Self - SontagDocument23 pagesOn Self - SontagCaleb DaliNo ratings yet

- EarlDocument18 pagesEarlEarl Russell S PaulicanNo ratings yet

- The Summoning J P Smith 2 Ebook Full ChapterDocument51 pagesThe Summoning J P Smith 2 Ebook Full Chapterrobert.liu806100% (7)

- As It WasDocument228 pagesAs It WasSebastian MendozaNo ratings yet

- Victor Hugo-The Last Day of A Condemned ManDocument29 pagesVictor Hugo-The Last Day of A Condemned ManIshan Marvel50% (2)

- The Perils of Indifference by Elie Wiesel 1Document3 pagesThe Perils of Indifference by Elie Wiesel 1api-707490871No ratings yet

- Malick e HeideggerDocument30 pagesMalick e HeideggerWilliam Joseph CarringtonNo ratings yet

- Theory of The Avante-Garde (Excerpts)Document21 pagesTheory of The Avante-Garde (Excerpts)Casey GoughNo ratings yet

- Diderot's HospitalityDocument27 pagesDiderot's HospitalityCasey GoughNo ratings yet

- Female Power in Family TiesDocument36 pagesFemale Power in Family TiesCasey GoughNo ratings yet

- 00 Huidobro Weintraub IntroDocument13 pages00 Huidobro Weintraub IntroCasey GoughNo ratings yet

- Shklovsky ArendtDocument31 pagesShklovsky ArendtCasey GoughNo ratings yet

- O'Gormanpart 1Document28 pagesO'Gormanpart 1Casey GoughNo ratings yet

- Notes On Popular CultureDocument46 pagesNotes On Popular CultureCasey GoughNo ratings yet

- Family PlanningDocument13 pagesFamily PlanningYana PotNo ratings yet

- Metamorphoses of Antoninus LiberalisDocument127 pagesMetamorphoses of Antoninus Liberalisamu_reza6821100% (1)

- Mco BookDocument985 pagesMco BookMuurish DawnNo ratings yet

- Isabelo V. Velasquez For Appellant. Assistant Solicitor General Jose G. Bautista and Solicitor Jorge R. Coquia For AppelleeDocument3 pagesIsabelo V. Velasquez For Appellant. Assistant Solicitor General Jose G. Bautista and Solicitor Jorge R. Coquia For AppelleejojoNo ratings yet

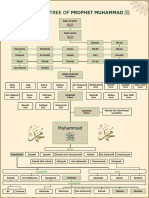

- Family Tree of Prophet MuhammadDocument1 pageFamily Tree of Prophet Muhammadgoogle pro100% (6)

- Political Law Syllabus-Based CodalDocument19 pagesPolitical Law Syllabus-Based CodalAlthea Angela GarciaNo ratings yet

- Moot Court Memorials Part FinalDocument4 pagesMoot Court Memorials Part FinalJoey AustriaNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Principles and State PoliciesDocument2 pagesFundamental Principles and State PoliciesRoselle LagamayoNo ratings yet

- 3 Circular NR 17, DND, Afp DTD 02 October 1987, Subject Administrative Discharge Prior To Expiration of Term of EnlistmentDocument12 pages3 Circular NR 17, DND, Afp DTD 02 October 1987, Subject Administrative Discharge Prior To Expiration of Term of EnlistmentCHRIS ALAMATNo ratings yet

- Multiculturalism in Dominican RepublicDocument1 pageMulticulturalism in Dominican RepublicLeo 6 God blessNo ratings yet

- Buet Torture AccountDocument28 pagesBuet Torture AccountNakibur Rahman100% (1)

- People V Mandorio (From Scribd)Document1 pagePeople V Mandorio (From Scribd)LawstudentArellanoNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals: PublishedDocument15 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals: PublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 1 JurisprudenceDocument19 pages1 JurisprudenceCindy Bacsal TrajeraNo ratings yet

- Marian Apparitions in Cultural Contexts Applying Jungian Concepts To Mass Visions of The Virgin MaryDocument246 pagesMarian Apparitions in Cultural Contexts Applying Jungian Concepts To Mass Visions of The Virgin MaryAlguém100% (1)

- De Thi Noi Mon Tieng Anh Lop 6 Hoc Ki 1Document6 pagesDe Thi Noi Mon Tieng Anh Lop 6 Hoc Ki 1Tan Tai NguyenNo ratings yet

- LawDocument12 pagesLawUdit SabooNo ratings yet

- Trim - General StabilityDocument7 pagesTrim - General StabilityNeeraj RahiNo ratings yet

- Law of Meditaion in JordanDocument3 pagesLaw of Meditaion in JordanmerahoraniNo ratings yet

- Doctor de Soto: Pinch of Salt." How Did The Fox Feel? He FeltDocument3 pagesDoctor de Soto: Pinch of Salt." How Did The Fox Feel? He FeltRenz Daniel Demathink100% (1)

- Affidavit of ExplanationDocument4 pagesAffidavit of ExplanationLorie Boy EndicoNo ratings yet

- White ChristmasDocument7 pagesWhite ChristmasSara RaesNo ratings yet

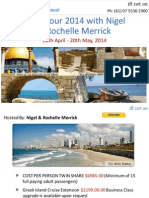

- Israel Tour 2014 With Nigel & Rochelle MerrickDocument20 pagesIsrael Tour 2014 With Nigel & Rochelle MerrickInnerFaithTravelNo ratings yet

- Land Sale Agreement Between Chief Kayode and Miss GegelesoDocument3 pagesLand Sale Agreement Between Chief Kayode and Miss GegelesoDolapo AmobonyeNo ratings yet

- LEGAL NOTICE NAME DECLARATION AND PROCLAMATION Temple #6Document2 pagesLEGAL NOTICE NAME DECLARATION AND PROCLAMATION Temple #6akenaten7ra7amen0% (1)

- How To Get Bail and Avoid Police Custody in A Dowry Case Under Section 498ADocument2 pagesHow To Get Bail and Avoid Police Custody in A Dowry Case Under Section 498Athakur999No ratings yet

- Compassionate Act of MercyDocument3 pagesCompassionate Act of MercyMhel Andrew Valbuena Melitante100% (1)

- Statement by President Uhuru Kenyatta On The Terrorist Attack at Garissa University College, Garissa CountyDocument5 pagesStatement by President Uhuru Kenyatta On The Terrorist Attack at Garissa University College, Garissa CountyState House KenyaNo ratings yet

- 9 11 12 0204 63341 Shoeless Jim Leslie Email To WCPD LeslieDocument10 pages9 11 12 0204 63341 Shoeless Jim Leslie Email To WCPD LeslieDoTheMacaRenoNo ratings yet

- Heraldic Code of The PhilippinesDocument59 pagesHeraldic Code of The PhilippinesJohana MiraflorNo ratings yet