Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Conceptual Framework For Understanding The Effects of CSR Marketing On Consumer

Uploaded by

alzghoul0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views13 pagesit is about CSR and its effects on consumers

Original Title

A Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Effects of CSR Marketing on Consumer

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentit is about CSR and its effects on consumers

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views13 pagesA Conceptual Framework For Understanding The Effects of CSR Marketing On Consumer

Uploaded by

alzghoulit is about CSR and its effects on consumers

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 13

A Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Effects

of Corporate Social Marketing on Consumer Behavior

Yuhei Inoue

Aubrey Kent

Received: 27 November 2012 / Accepted: 6 May 2013 / Published online: 16 May 2013

Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013

Abstract This theoretical paper develops a conceptual

framework that explains how companies can inuence

consumer behavior in terms of both social and business

benets through their corporate social marketing (CSM)

initiatives. Drawing from the source credibility literature,

the article asserts that the effectiveness of CSM depends

largely on the corporate credibility of a company in sup-

porting a social cause (CSM credibility). Based on this

assertion, the framework identies ten different anteced-

ents of CSM credibility, which are organized into (1)

attributes of the company, (2) attributes of the CSM ini-

tiative, and (3) attributes of the cause. Furthermore, this

framework shows that CSM credibility affects the two

examined consequences, intended prosocial behavior and

consumer loyalty. Several research and managerial impli-

cations are developed based on the propositions specied

in the framework.

Keywords Corporate social marketing Corporate social

responsibility Corporate credibility Value congruence

Customer loyalty Prosocial behavior

Introduction

In 1971, Kotler and Zaltman proposed the concept of social

marketing, referring to the design, implementation, and

control of programs calculated to inuence the accept-

ability of social ideas (p. 5). This concept has received

immense attention from researchers in marketing and other

disciplines and has been used to assess the effectiveness of

interventions designed to inuence ones voluntary

behavior related to areas such as health, community

involvement, injury prevention, and environmental pro-

tection (e.g., Andreasen 2004; Kotler et al. 2002;

McKenzie-Mohr and Smith 1999; Stead et al. 2007). Fur-

thermore, although the literature traditionally examined

social marketing programs implemented by government

agencies and nonprot organizations, this concept has been

relatively recently extended to a corporate context (Bloom

et al. 1997; Kotler and Lee 2005a, b). In short, the major

goal of corporate social marketing (CSM) initiatives is to

persuade consumers to perform desired prosocial behavior

(Bloom et al. 1997; Kotler and Lee 2005a, b). This inten-

ded inuence on behavior change distinguishes CSM from

other types of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activ-

ities implemented by rms, such as corporate philanthropy

and cause-related marketing, whose main aim is to raise

goodwill, money, and recognition of a cause, but not to

inuence or change ones behavior (Bloom et al. 1997;

Kotler and Lee 2005a). Examples of CSM efforts include

the Change Your Clock Change Your Battery Campaign

launched by the Energizer Battery Company, which

encourages individuals to make sure if their smoke alarms

are properly working and change alarm batteries on a

regular basis, to reduce the number of home re fatalities

(Energizer 2010). Coca-Cola established its subsidiary

Coca-Cola Recycling in 2007 to promote the recycling of

Y. Inoue (&)

Department of Health and Sport Sciences, The University

of Memphis, 208 Elma Roane Fieldhouse, Memphis,

TN 38152, USA

e-mail: yinoue@memphis.edu

A. Kent

School of Tourism & Hospitality Management, Temple

University, 349A Speakman Hall, 1810 N. 13th St., Philadelphia,

PA 19122, USA

e-mail: aubkent@temple.edu

1 3

J Bus Ethics (2014) 121:621633

DOI 10.1007/s10551-013-1742-y

beverage bottles and cans among consumers through the

installations of recycling bins and the communication of

recycling message (Coca-Cola Recycling, n.d.).

Given its intended inuence on consumer prosocial

behavior, CSM should create the greatest social benets

among other CSR activities (Kotler and Lee 2005a, b).

Furthermore, since CSM effects on voluntary behavior

should likely be translated into effects on customer

behavior, CSM is considered best of breedin terms of

support for marketing goals and objectives (Kotler and

Lee 2005b, p. 92). However, despite this acknowledged

effectiveness of CSM in generating social and business

returns, there has been limited research explicitly exam-

ining the process of how CSM inuences these outcomes

(Du et al. 2008; Peloza and Shang 2011). This is due to the

tendency of business scholars to focus mainly on limited

kinds of CSR activities, such as cause-related marketing

and philanthropy (Kotler and Lee 2005b; Maignan and

Ferrell 2004). Peloza and Shangs (2011) review of exist-

ing CSR studies, for example, showed that while over half

of the 163 reviewed articles investigated either cause-

related marketing (51 studies) or corporate donations (33

studies), none of them specically tested the effect of CSM

initiatives on consumer-related outcomes.

As an exception, although not identied in Peloza and

Shangs (2011) review, Du et al. (2008) investigated the

effectiveness of a companys CSM program that aimed to

promote oral care behavior on the intended health and

customer behaviors among program participants. While

the results showed that the program successfully promoted

oral health behavior and further beneted the company

through the participants increased reciprocal behavior, the

study focused solely on the moderating effects of a few

personal characteristics (e.g., level of acculturation among

the participants) to understand CSM effects. Drawing

from the social psychology literature (e.g., Petty and

Cacioppo 1981; Petty and Wegener 1998), however, the

effectiveness of CSM on ones behavior may be deter-

mined by not only the personal characteristics of partici-

pants but also the characteristics of: (1) the organization

implementing a CSM campaign (i.e., source characteris-

tics), (2) communication strategies used in the campaign

(i.e., message characteristics), and (3) the context where

the organization implements the campaign (i.e., context

characteristics).

Indeed, the characteristics noted above have been shown

to inuence the effectiveness of social marketing inter-

ventions implemented by nonprots and governmental

agencies (e.g., Bendapudi et al. 1996; Keller and Lehmann

2008; McKenzie-Mohr and Smith 1999). As CSM is an

extension of the general social marketing framework

(Bloom et al. 1997; Kotler and Lee 2005a, b), these nd-

ings identied in the context of nonprots and

governmental agencies should be largely applicable to the

CSM context. Nevertheless, Bloom et al. (1997) argue that

a signicant difference exists between general social mar-

keting initiatives and CSM initiatives in source character-

istics, especially in terms of the degree of credibility

perceived by audiences. That is, a corporation may have

less credibility with a target audience than the government

or a nonprot, hurting the persuasive ability of its mes-

sage (Bloom et al. 1997, p. 18). This notion that com-

panies may be seen as less credible sources of promoting

prosocial behavior is signicant because the credibility of

an organization is one of the most critical elements in

determining the effectiveness of its social marketing

campaign (Bendapudi et al. 1996; Craig and McCann 1978;

McKenzie-Mohr and Smith 1999).

Consequently, a clear need exists to understand what

factors may inuence the credibility of companies, or

corporate credibility, with respect to CSM involvement in

order for them to effectively promote desired prosocial

behavior. The purpose of this article, therefore, is to

develop a conceptual framework that explains how com-

panies might inuence consumer behavior in terms of both

social and business benets through CSM by focusing on

the role of corporate credibility.

CSM, CSR, and the Ethical Responsibility of Business

Before presenting our conceptual framework on CSM, we

provide a further understanding of this concept by clari-

fying its linkage with CSR and the ethical responsibility

of business. First, while CSM originates from social

marketing introduced by Kotler and Zaltman (1971), the

recent literature (e.g., Du et al. 2008; Kotler and Lee

2005a) has examined this concept in the framework of

CSR, or a companys commitment to improve commu-

nity well-being through discretionary business practices

and contributions of corporate resources (Kotler and Lee

2005a, p. 3). According to Kotler and Lee (2005a),

companies can assume their CSR by undertaking several

types of voluntary activities, collectively referred to as

corporate social initiatives, and CSM represents one type

of such initiatives.

It should be noted that although a companys engage-

ment in corporate social initiatives including CSM allows it

to demonstrate its CSR as dened above or its philan-

thropic responsibility, this does not necessarily mean that

the company assumes its ethical responsibility (Carroll

1979, 1991). Specically, the ethical responsibility of

business is based on the principle of business ethics, which

addresses fairness and morality in business-related prac-

tices and actions (Carroll and Buchholtz 2012), and refers

to meeting expectations that reect a concern for what

622 Y. Inoue, A. Kent

1 3

consumers, employees, shareholders, and the community

regard as fair, just, or in keeping with the respect or pro-

tection of stakeholders moral rights (Carroll 1991, p. 41).

This type of responsibility differs from the philanthropic

responsibility, which includes voluntary roles assumed by

corporations through the implantation of corporate social

initiatives, due to the fact that the latter exceeds the ethical

or moral expectations of the society (Carroll 1991). Nike is

a classic case of a corporation that shows its philanthropic

responsibility but fails to achieve its ethical responsibility

as it currently implements a number of corporate social

initiatives but has been accused of poor working conditions

in Asian countries.

However, as later discussed by Carroll who originally

made the distinction between the ethical and philanthropic

responsibilities, it is sometimes difcult to distinguish

between philanthropic and ethical activities on both a

theoretical and practical level (Schwartz and Carroll

2003, p. 506). For example, the implementation of corpo-

rate social initiatives, such as CSM, is thought to be con-

sistent with the ethical principle of utilitarianism, which

emphasizes the importance of maximizing the public

welfare (Schwartz and Carroll 2003). Despite this, we

acknowledge that the framework demonstrated below

focuses mainly on providing insight into the CSR or phil-

anthropic responsibility of business, and may have limited

implications for its ethical responsibility.

Conceptual Framework

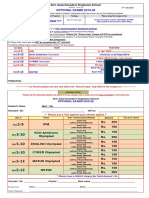

We propose a conceptual framework that explains how

companies might inuence consumer behavior through

their CSM initiatives (Fig. 1). Our central assertion is that

the effectiveness of CSM depends largely on the corporate

credibility of a company in supporting a social cause

(hereafter called CSM credibility). The current frame-

work thus intends to specify the antecedents and conse-

quences of CSM credibility in the following ways. First,

this framework proposes that antecedents of CSM credi-

bility can be organized into three categories: (1) attributes

of the company, (2) attributes of the CSM campaign, and

(3) attributes of the cause. Based on implications drawn

from the existing literature (e.g., Becker-Olsen et al. 2006;

Haley 1996; Rifon et al. 2004), the framework further

identies several attributes for each category. Moreover,

building on the source credibility literature (e.g., Hovland

et al. 1953; MacKenzie and Lutz 1989) and Kelmans

(1958, 1961, 2006) theory of internalization, CSM credi-

bility is proposed to have effects on the two types of

consumer behavior, desired prosocial behavior and cus-

tomer loyalty, both directly and through the mediation of

value congruence.

Corporate Credibility

In the early 1950s, Hovland proposed that the credibility of

message sources (e.g., individuals, groups, organizations)

play an important role in determining the persuasiveness of

a communication (Hovland et al. 1953; Hovland and Weiss

19511952; Kelman and Hovland 1953). Since then, a

substantial body of the literature has investigated whether a

high-credibility source produces more persuasion toward

an advocacy message than a low-credibility source (e.g.,

Kelman 1958; Maddux and Rogers 1980; Mills and Harvey

1972). When broadly dened, source credibility refers to

one aspect of a source that presents a persuasive message

(Petty and Wegener 1998). In a more specic manner,

Kelman (1961) dened source credibility as the state of

being perceived as expert and trustworthy, and thereby

being seen as worthy of serious consideration by others. As

this denition suggests, source credibility consists of two

dimensions: expertise and trustworthiness (Hovland et al.

1953; Kelman 1961; McCracken 1989; Petty and Wegener

1998; Pornpitakpan 2004). Expertise refers to the perceived

ability of a source to provide precise information (Petty and

Wegener 1998), while trustworthiness refers to its per-

ceived willingness to provide accurate information (McC-

racken 1989).

Despite the richness of the source credibility literature,

the early work mainly focused on the credibility of indi-

viduals, such as celebrities or spokespersons (e.g., Kelman

1958; McCracken 1989; Ohanian 1990), and the investi-

gation of the credibility of companies, or corporate credi-

bility, has lagged (Haley 1996; Lafferty and Goldsmith

1999; Newell and Goldsmith 2001; Pornpitakpan 2004). As

one of the rst studies examining corporate credibility,

MacKenzie and Lutz (1989) investigated how advertiser

credibility, dened as the perceived trustworthiness of the

sponsor of the advertisement, inuences consumer attitudes

toward the advertisement. Results indicated that advertiser

credibility had a signicant positive effect on both adver-

tisement credibility and attitude toward the advertiser.

These two variables, in turn, positively affected attitude

toward the advertisement (Mackenzie and Lutz 1989). In a

related study, Goldberg and Hartwick (1990) tested the

interaction effect between advertiser reputation, repre-

senting the perceived expertise and trustworthiness of the

sponsoring company, and the extremity of advertising

claims on product evaluation and advertisement credibility.

Moreover, Lafferty and Goldsmith (1999) investigated the

effects of corporate credibility on consumer attitudes

toward the advertisement, attitudes toward the brand, and

purchase intentions, and found that corporate credibility

had a signicant main effect on each of the three outcomes

without any interactions with endorser credibility (Lafferty

and Goldsmith 1999). More interestingly, their results

Effects of CSM on Consumer Behavior 623

1 3

highlighted the signicance of corporate credibility by

revealing that the effect of corporate credibility on attitude

toward the brand and purchase intention was greater than

the effect of endorser credibility (Lafferty and Goldsmith

1999).

Although the earlier studies on corporate credibility

showed consistent support for the signicant effect of the

construct on consumer attitudes and behavior, there was a

lack of consensus about what corporate credibility repre-

sents (Newell and Goldsmith 2001). Goldsmith and his

colleagues (Goldsmith et al. 2000; Newell and Goldsmith

2001), however, made a substantial contribution to the

conceptualization of the construct in the following two

aspects. First, the researchers claried the distinction

between corporate credibility and reputation by arguing

that reputationis much broader in scope and includes,

but is not limited to [credibility] (Goldsmith et al. 2000,

p. 44). That is, corporate credibility represents one com-

ponent of corporate reputation, but the latter construct

incorporates other corporate characteristics, such as

responsibility (Fombrun 1996; Goldsmith et al. 2000).

Second, in line with the implications of the source credi-

bility literature (Hovland et al. 1953; Kelman 1961;

McCracken 1989), they explicitly indicated that corporate

credibility consists of the expertise and trustworthiness

dimensions (Goldsmith et al. 2000; Newell and Goldsmith

2001). In particular, corporate expertise refers to the

extent to which consumers feel that the rm has the

knowledge or ability to fulll its claim (Newell and

Goldsmith 2001, p. 235), and corporate trustworthiness

refers whether the rm can be trusted to tell the truth or

not (Newell and Goldsmith 2001, p. 235).

Antecedents of CSM Credibility

Researchers have identied several factors that may inu-

ence consumer perceptions of corporate credibility (e.g., de

Ruyter and Wetzels 2000; Haley 1996; Keller and Aaker

1998; Newell and Goldsmith 1998). For instance, Keller

and Aaker (1998) proposed that corporate credibility would

be affected by a companys innovativeness, support for the

environment, and community involvement. Results indi-

cated that all three factors had a positive effect on each of

the trustworthiness and expertise dimensions of corporate

credibility (Keller and Aaker 1998). de Ruyter and Wetzels

(2000) also found that consumer evaluation of a rms

corporate credibility varied depending on the nature of its

brand extension; a rm described as extending its brand to

a related market was perceived as more credible than

another rm described as expanding into an unrelated

market. Newell and Goldsmith (1998) further examined

how the characteristics of advertising messages would

affect the perceived credibility of a company. Their nd-

ings showed that consumers tended to rate the company

low in credibility when its advertisement contained a

deceptive claim on its environmental efforts.

While the above studies investigated determinants of

corporate credibility in general, Haley (1996) conducted

semi-structured interviews with 97 consumers to identify

factors that may inuence the credibility of organizations

(both companies and nonprot organizations) with respect

to their advocacy advertising campaigns (e.g., campaigns

that promote the importance of safe driving). Haley iden-

tied that the antecedents of organizational credibility in

this regard can be classied into three categories: (1)

characteristics of the organization, (2) characteristics of the

campaign, and (3) characteristics of the issue. The rst

category entails general characteristics of the organization

perceived by consumers (e.g., liking, familiarity), regard-

less of its involvement in advocacy advertising. The second

category involves attributes of the campaign, such as the

congruence between the organizations image and that of

the sponsored issue, the extent of expertise that the orga-

nization has in supporting the issue, and the perceived

P8-P10

P1-P2

P3-P7 P13

P14

P15

Corporate Attributes

- CSR associations

- CA associations

CSM credibility

CSM Attributes

- Company-cause fit

- Effort

- Personal investment

- Value-driven motives

- Impact

Cause Attributes

- Personal importance

- Cause proximity

- Familiarity

Value congruence

Intended

prosocial

behavior

Customer loyalty

P11

P12

Fig. 1 A conceptual framework for understanding the effects of corporate social marketing on consumer behavior

624 Y. Inoue, A. Kent

1 3

motive behind the organizations sponsorship of the cam-

paign. The third category encompasses consumers per-

ception of the cause, such as its importance to them and to

society (Haley 1996). Similar to Haleys ndings, Speed

and Thompson (2000) empirically demonstrated that con-

sumers evaluations of a companys sponsorship of a sport

event were determined by their perceptions of the company

(e.g., attitude toward the company), sponsorship (e.g.,

company-event t), and the event (e.g., status of the event).

A conceptual framework developed by Du et al. (2010)

also used these three categories to identify factors that

determine the effect of a companys CSR activities on

internal and external outcomes.

Drawing from the studies (Du et al. 2010; Haley 1996;

Speed and Thompson 2000), we propose that the factors

that inuence the CSM credibility of the company can be

classied into (1) attributes of the company, (2) attributes

of the CSM initiative, and (3) attributes of the cause. The

following sections identify specic attributes included in

each of the three categories and offer propositions

regarding how these attributes inuence CSM credibility.

Corporate Attributes Inuencing CSM Credibility

CSR associations refer to how well a company meets its

societal obligations through charitable and other corporate

social initiatives (Brown and Dacin 1997; Lichtenstein

et al. 2004; Sen et al. 2006). This construct captures a

rms overall social activities more than its involvement in

a specic CSM initiative (Kotler and Lee 2005a), and there

is some evidence that CSR associations inuence corporate

credibility (Keller and Aaker 1998; Walker and Kent

2012). Keller and Aaker (1998) found that a companys

involvement in environmental and community issues sig-

nicantly increased two dimensions of corporate credibility

including perceived trustworthiness and expertise. This

nding is replicated by Walker and Kent (2012), who

identied that consumers tended to perceive the PGA

TOUR as a credible organization if they were aware of its

CSR activities. Keller and Aaker (1998) suggest that this is

due to the ability of a company, through CSR, to demon-

strate its understanding of customer needs, which leads to

high trustworthiness. In addition, given that active social

involvement tends to require the adoption of advanced

technologies, rms with high social involvement may be

perceived as having expertise (Keller and Aaker 1998),

especially in addressing social causes. Based on these

arguments, we propose that a rms CSR associations have

a positive effect on its credibility in CSM involvement.

P1 Companies with more positively rated CSR associa-

tions gain higher CSM credibility than companies with

more negatively rated CSR associations.

Along with CSR associations, Brown and Dacin (1997)

identied the other type of corporate associations, namely

corporate ability (CA). The construct represents a com-

panys capability to produce quality services and products,

and has been found to have effects on consumer evaluations

of the company and its products (Brown 1998; Brown and

Dacin 1997; Sen et al. 2006). According to Brown and Dacin

(1997), CA associations inuence consumers perceptions

by providing cues about certain attributes of the company

especially when knowledge of these attributes is lacking. In

line with this, social psychology research has suggested that

ones general perception of an object may serve as a direct

predictor of perception of specic aspects of that same object

(Eagly and Chaiken 1998). Corporate credibility researchers

have also argued that individuals develop the perceived

credibility of a specic aspect of a company based on its

overall perceptions and images (Haley 1996; MacKenzie and

Lutz 1989). MacKenzie and Lutz (1989), for example,

demonstrated that consumers perceived credibility of a

claim about an advertisers brand in an ad was affected by

their perceived credibility of the advertiser in general. Haley

(1996) also documented that consumers tended to evaluate a

company as a credible source of an advocacy message if the

company offers a quality product and/or service. Consistent

with this line of research, this study proposes that a com-

panys CA association serves as an antecedent of its credi-

bility in CSM involvement.

P2 Companies with more positively rated CA associa-

tions in terms of their products and/or services gain higher

CSM credibility than companies with more negatively

rated CA associations.

CSM Attributes Inuencing CSM Credibility

Bloom et al. (1997) discussed that CSM programs can be

differentiated by the extent to which the supported cause is

tied with the companys operations and products. For

example, while consumers may perceive a high t between

Energizers operations (i.e., manufacturing of batteries)

and its promotion of changing smoke alarm batteries

through the Change Your Clock Change Your Battery

campaign, they may not see a strong connection between

Avons operations (i.e., selling of cosmetic products) and

its Breast Cancer Crusade that aims to educate cus-

tomers about the importance of early detection efforts for

breast cancer. Subsequent empirical studies suggest that the

extent of company-cause t has a signicant effect on

consumer perceptions of companies (e.g., Basil and Herr

2003, 2006; Lafferty et al. 2004; Lichtenstein et al. 2004;

Simmons and Becker-Olsen 2006). For example, Basil and

Herr (2006) demonstrated that the t between a companys

business and its sponsored nonprots led to a more positive

Effects of CSM on Consumer Behavior 625

1 3

attitude toward the company. Rifon et al. (2004) and

Becker-Olsen et al. (2006) provided direct evidence that

consumers evaluated a company as more credible when it

supported a cause congruent with its operations than an

incongruent cause. A high t between the rm and the

cause is thought to affect a companys credibility by

increasing its perceived expertise in addressing a given

social cause (Haley 1996). In addition, consumers tend to

associate rms with altruistic motives in high t conditions,

leading to increased trustworthiness (Rifon et al. 2004).

Collectively, evidence suggests that the perceived t

between the company and the cause for which it advocates

positively inuences its corporate credibility in supporting

the cause, leading to the following proposition:

P3 Companies gain higher CSM credibility when they

support social causes that are congruent with their opera-

tions and products than when they support social causes

that are incongruent.

Effort refers to the amount of energy companies put into

their CSM programs to promote desired prosocial behavior

(Ellen et al. 2000). Du et al. (2010) discussed that the effect

of corporate social initiatives on consumer evaluations of a

rm may depend in part on the amount of input invested by

the rm. Experimental research has shown that the per-

ceived level of corporate effort can, in fact, signicantly

inuence consumer perceptions of the company and its

social initiatives (Ellen et al. 2000; Reed et al. 2007). In

Reed et al.s (2007) study, consumers with high moral

identity evaluated a company adopting an employee vol-

unteer program (i.e., high effort) as more socially respon-

sible than a company merely engaging in giving cash (i.e.,

low effort). Ellen et al. (2000) also demonstrated that

product donations (i.e., high effort) led to a more positive

consumer evaluation than cash donations (i.e., low effort).

Although CSM generally requires more inputs than other

CSR activities (Kotler and Lee 2005a, b), some CSM ini-

tiatives (e.g., Coca-Colas recycling program through the

establishment of its subsidiary, Coca-Cola Recycling) may

be considered more effortful than others (e.g., Staples in-

store recycling program as part of the companys envi-

ronmental efforts).Thus, if consumers perceive that the

company has made a large effort in its CSM initiative, they

are more likely to perceive it as credible in supporting the

cause. This leads us to the following proposition:

P4 Companies gain higher CSM credibility when they

put a large amount of effort in their CSM initiatives than

when they put a low amount of effort.

Personal investment refers to the degree to which the

members of the organization are personally involved in the

cause (Haley 1996). Although the literature has not

extensively examined the effect of this attribute, Haleys

qualitative study provided a consumer view that they ten-

ded to perceive an organizations advocacy advertising as

more trustworthy when its members were greatly involved

in the cause. For example, a participant noted: the thing

that makes MADD [Mothers Against Drunk Driving] such

a good sponsor is that those mother have experienced

personally the pain of drinking and driving (Haley 1996,

p. 29). Given this, the company will likely increase its

credibility as to addressing a social cause if consumers

perceive that its management and/or employees have high

personal investment in the cause. Therefore, our next

proposition is:

P5 Companies gain higher CSM credibility when their

employees and/or management show personal investment

in the supported social causes than when they do not.

Rifon et al. (2004) identied the signicant effect of

perceived intent on corporate credibility in that a rm

implementing an initiative based on altruistic motives

tended to receive higher corporate credibility ratings. This

nding that a rms intent behind social involvement

affects consumer evaluations of the company, including

corporate credibility, was further supported by Barone

et al. (2000), Menon and Kahn (2003), Yoon et al. (2006),

and Speed and Thompson (2000). In addition, in Haleys

(1996) study, consumers indicated that they were less

likely to trust a company if its initiative was clearly used

for generating mere publicity.

While the above studies divided corporate motives into

either economic or altruistic motives, Ellen et al. (2006)

found that each of the two motives can be further classied

into two different kinds of motives, resulting in the fol-

lowing four types of motives: (1) egoistic-driven, (2)

strategic-driven, (3) stakeholder-driven, and (4) value-dri-

ven motives. The rst two motives constitute economic

motives but differ in terms of whether the company sup-

ports the cause to simply exploit it for publicity and tax

exemptions (egoistic-driven) or to achieve its business

goals, such as increasing sales and customers (strategic-

driven). The last two motives represent altruistic motives

but can be distinguished by whether the company engages

in social activities due to pressure from stakeholders

(stakeholder-driven) or due to its sincere motivation to

society (value-driven). Using this typology, a latter study

by Vlachos et al. (2009) identied that the four types of

motives had differential effects on consumer perception of

trust in the company, such that only CSR activities asso-

ciated with value-driven motives had a positive effect on

the outcome.

Relating to the different effects of the two altruistic

motives, Becker-Olsen et al. (2006) further proposed that a

corporate social initiative implemented as a reaction to

some negative actions and external pressures, such as

626 Y. Inoue, A. Kent

1 3

consumer boycott, would likely decrease the perceived

trust and honesty of the rm among consumers. The results

support this proposition by showing that a company

described as implementing a reactive initiative is perceived

as less credible than a company described as implementing

a proactive initiative (Becker-Olsen et al. 2006). These

ndings thus suggest that companies can gain high CSM

credibility only when their CSM involvement is viewed as

proactive and being motivated by sincere intentions (i.e.,

value-driven), leading to the following proposition:

P6 Companies gain higher CSM credibility when their

CSM involvement is associated with value-driven motives

than when it is associated with egoistic-, strategic-, or

stakeholder-motives.

CSM initiatives may further vary according to the amount

of benets accrued to an individual through the performance

of the intended prosocial behavior (Bloom et al. 1997),

something which Du and her colleagues (Du et al. 2008, 2009,

2010) explicitly examined with regard to consumer-related

outcomes. Specically, Du et al. (2008) found that the per-

ceived impact of Crests Healthy Smiles 2010 campaign

positively inuenced reciprocal intentions of participant par-

ents, such as buying products of the brand. In their 2009 study,

the researchers provided similar results, suggesting that con-

sumers were more likely to engage in advocacy behavior

toward a company if they perceived that its initiative made a

signicant impact on society. Their latest work further noted

that the perceived impact of CSRactivities would likely affect

consumer perceptions of the company, such as trust. Based on

the implications of these studies, it is likely that consumers see

the company as more credible in supporting a social cause if

they think that its CSM initiative have provided (or will pro-

vide) benets to them and society. Hence we propose:

P7 Companies gain higher CSM credibility when they

demonstrate the impacts of their CSM initiatives than when

they do not.

Cause Attributes Inuencing Corporate Credibility

Previous research has identied that the personal impor-

tance of the cause, or the degree to which consumers

personally support the companys sponsoring cause, has a

signicant effect on their perceptions of the company

(Marin and Ruiz 2007; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001). For

example, Sen and Bhattacharya (2001) found that con-

sumers were more likely to identify with a company when

they perceived the social issue supported by the rm as

important for themselves. Marin and Ruiz (2007) also

showed that consumers who were highly supportive of

corporate involvement in social issues tended to perceive

higher congruence between them and a socially responsible

rm. The expected effect of cause importance on corporate

credibility can be explained by the notion that consumers

consider a company similar to them if it addresses a cause

that is important for them (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003).

Hovland et al. (1953) propose that individuals tend to see a

source as credible when they perceive a high similarity

with it. Thus, the personal importance of the cause may

affect the CSM credibility of the company due to the

consumer perceived similarity with the company, leading

us to the following proposition:

P8 Consumers are more likely to perceive the company

as having high CSM credibility when it supports a social

cause that is personally important to them than when it

supports a social cause that is not personally important.

Some CSM initiatives are designed to support causes

that are relevant to local communities. For example, in

response to growing concern about water conservation in

Arizona, all of the Home Depots Arizona stores joined a

water conservation campaign in 2003 to teach consumers

about effective ways of saving water (Kotler and Lee

2005b). Relating to this, Grau and Folse (2007) examined

the effect of cause proximity by testing whether corporate

involvement in a local cause would generate more positive

reactions than involvement in a national cause based on the

assumption that consumers are likely to place a greater

importance on the former than the latter. Results were

supportive of this proposition; consumers indicated a more

positive perception when a ctitious rm was described as

supporting local skin cancer research than when described

as supporting national skin cancer research (Grau and Folse

2007). Based on this nding, we propose that CSM ini-

tiatives that support locally positioned causes are likely to

enhance the CSM credibility of companies.

P9 Consumers are more likely to perceive the company

as having high CSM credibility when it supports a locally

positioned cause than when it supports a cause that is not

locally positioned.

Furthermore, Lafferty et al. (2004) demonstrated that

consumers tended to formulate positive perceptions of a

company if the cause supported by the rm is familiar to

them. This effect of familiarity can be explained by the

attitude accessibility theory, which suggests that accessible

memory plays an important role in evaluating an attitude

object (Petty and Wegener 1998). From this theory, a

highly familiar cause is thought to enable consumers to

easily retrieve memory about the cause and the CSM ini-

tiative, leading them to perceive high credibility about the

sponsor company (Lafferty et al. 2004). This leads us to

propose:

Effects of CSM on Consumer Behavior 627

1 3

P10 Consumers are more likely to perceive the company

as having high CSM credibility when it supports a social

cause that is familiar to them than when it supports a social

cause that is unfamiliar.

Consequences of CSM Credibility

Direct Effect of CSM Credibility on Intended Prosocial

Behavior

The role that the credibility of message sources plays in

determining the persuasiveness of a communication has been

examined since the early 1950s (e.g., Hovland et al. 1953;

Hovland and Weiss 19511952; Kelman and Hovland 1953).

This line of research has consistently shown that a high-

credibility source generally produces a more persuasive

advocacy message than a low-credibility source (e.g., Kel-

man 1958; Maddux and Rogers 1980; Mills and Harvey

1972; Pornpitakpan 2004). This notion can also be applied to

the promotion of prosocial behavior (Bendapudi et al. 1996;

Craig and McCann 1978; McKenzie-Mohr and Smith 1999).

For example, Bendapudi et al. (1996) indicated that organi-

zational credibility was the single most critical element in

determining the effectiveness of interventions by nonprot

organizations that are designed to promote donation activi-

ties. Craig and McCann (1978) found that local residents

were more likely to engage in energy conservation activities

when they received a pamphlet froma highly credible source

(the State Regulatory Agency) than a low credible source (a

local utility rm). Consequently, it can be proposed that a

companys CSM credibility positively affects consumer

decisions to perform prosocial behavior promoted by the

company through its CSM initiative.

P11 CSM credibility positively affects consumers deci-

sions to engage in the intended prosocial behavior.

Direct Effect of CSM Credibility on Customer Loyalty

Customer loyalty is dened as ones behavioral intentions

to buy the companys brand in the future, accompanied by

a high level of commitment (Evanschitzky and Wunderlich

2006; Homburg et al. 2010; Zang and Bloemer 2008).

Empirical evidence suggests that corporate credibility

signicantly affects ones attitudes and behavioral inten-

tions that are related to customer loyalty (e.g., Goldberg

and Hartwick 1990; Goldsmith et al. 2000; MacKenzie and

Lutz 1989; Lafferty and Goldsmith 1999). For example,

MacKenzie and Lutz (1989) showed that advertiser credi-

bility had direct effects on advertisement credibility and

attitudes toward the advertiser, and indirect effects on

attitude toward the advertisement through the mediation of

the two variables (Mackenzie and Lutz 1989). Goldsmith

and his colleagues conducted a series of experimental

studies examining the effects of corporate credibility on

consumers attitudes toward the advertisement and the

brand and their purchase intentions, and found that the

construct had a signicant main effect on each outcome

(Goldsmith et al. 2000; Lafferty and Goldsmith 1999). In a

more relevant study, Walker and Kent (2012) revealed that

corporate credibility enhanced by consumers awareness of

the PGA TOURs social initiatives had a signicant effect

on consumers loyalty to the organization operationalized

as advocacy and nancial sacrice. Based on these nd-

ings, we posit that CSM credibility is likely to have a direct

positive effect on customer loyalty to the company

implementing CSM.

P12 CSM credibility positively affects customer loyalty

to the company.

Mediating Effects of Value Congruence

While the aforementioned arguments suggest that CSM

credibility would have a direct effect on the two behavioral

consequences, Kelmans (1958, 1961, 2006) theory of

internalization explains that source credibility may inu-

ence individuals attitudes and behavior through the

mediation of value congruence. Value congruence refers to

the perceived similarity between an individuals values and

those of others (Chatman 1989; Edwards and Cable 2009;

Fombelle et al. 2011; Kristof 1996). Although some

overlap may exist between value congruence and cause

attributes discussed above, specically personal impor-

tance, they essentially differ in the following ways. First,

value congruence is concerned with values, which refer

to an individuals general beliefs on the signicance of a

certain end state or normatively desirable behavior (e.g.,

altruism, universalism, benevolence; Edwards and Cable

2009; Schwartz 1992); whereas personal importance

addresses the extent to which a given cause (e.g., breast

cancer, youth education, environmental protection) is per-

sonally important to that individual. Second, while per-

sonal importance rests on a persons perception of a cause,

value congruence is based on his or her perception of a

company in terms of how well pairs of components (i.e.,

values) t together (Nadler and Tushman 1980, p. 45)

between the person and the company.

Using value congruence, Kelman (1958, 1961, 2006), in

the context of persuasion, proposed that individuals tend to

perceive that actions and underlying values promoted by a

message source are congruent with their own values (i.e.,

value congruence) if they see the source as credible. Once

value congruence is activated, the individuals are likely to

incorporate the actions and values induced by the source

into their existing value systems (i.e., internalization). The

628 Y. Inoue, A. Kent

1 3

reorganized value systems, in turn, provide the individuals

with intrinsic needs that will be satised by performing

behavior consistent with the induced values and actions

(Kelman 1958, 1961, 2006). This perspective thus high-

lights the mediating effect of value congruence in the

relationship between CSM credibility and the two conse-

quences included in the framework. To demonstrate this

role of value congruence, we rst propose:

P13 CSM credibility increases perceived value congru-

ence with the company among consumers.

Indirect Effect of CSM Credibility on Intended Prosocial

Behavior through Value Congruence

Given the implications of value congruence explained

above, we propose that this construct at least partially

mediates the relationship between CSM credibility and

prosocial behavior. This is because CSM activities can be

seen as a communicator of the companys values; the

company communicates what it considers socially respon-

sible to consumers by promoting desired prosocial behavior

(Bhattacharya and Sen 2003). Therefore, if consumers

evaluate the company as credible and increase value con-

gruence, they are likely to restructure their value systems in

accordance with the behavior and values communicated by

the company through its CSM initiative. In turn, to fulll

resultant needs, consumers perform the intended prosocial

behavior whenever they encounter related issues (Kelman

1958, 1961, 2006). This leads us to propose:

P14 Value congruence enhanced by CSM credibility

positively affects consumers decisions to engage in the

intended prosocial behavior.

Indirect Effect of CSM Credibility on Customer Loyalty

through Value Congruence

Furthermore, while no research has explicitly examined the

link among corporate credibility, value congruence, and

behavioral loyalty, the literature collectively indicates that

value congruence activated by CSM credibility can have a

positive effect on customer loyalty (e.g., Sen and Bhattach-

arya 2001; Walker and Kent 2012; Zang and Bloemer 2008).

As noted, Walker and Kent (2012) showed the positive direct

effect of corporate credibility on customer loyalty. Sen and

Bhattacharya (2001) identied the mediating role of com-

panycustomer congruence in the relationship between CSR

and consumers evaluation of the company. In addition, in a

different research context, Zang and Bloemer (2008) showed

the signicant effect of value congruence between con-

sumers and a brand on their loyalty to the brand, operation-

alized as willingness to pay more, repurchase intention, and

positive word of mouth communication. Drawing fromthese

ndings, we posit that CSM credibility inuences customer

loyalty through the partial mediation of value congruence.

P15 Value congruence enhanced by CSM credibility

increases customer loyalty to the company.

Discussion and Implications

Despite the potential of CSM to create the greatest social

and business returns among other CSR activities (Kotler

and Lee 2005a, b), the business literature has provided little

insight into how CSM leads to these benets (Du et al.

2008). The current theoretical paper, therefore, addresses

this lack of knowledge by developing the conceptual

framework that species the antecedents and consequences

of corporate credibility regarding CSM involvement,

namely CSM credibility. The theoretical, research, and

managerial implications of this paper are as follows.

Theoretical Implications

First, the framework developed here shows that consumers

formulate their perceptions of CSM credibility based on

corporate, CSM, and cause attributes. While several studies

attempted to identify the antecedents of corporate credi-

bility (Becker-Olsen et al. 2006; Keller and Aaker 1998;

Walker and Kent 2012), this study is distinguishable from

them in terms of the identication of multiple antecedents,

systematic classication of the antecedents, and focus on

corporate credibility specic to CSM involvement. Fur-

thermore, our framework advances the frameworks pro-

posed by the previous studies (Du et al. 2010; Haley 1996;

Speed and Thompson 2000) by incorporating empirical

evidence and theoretical implications drawn from the

existing literature and by identifying a more comprehen-

sive set of the antecedents of CSM credibility.

Second, this framework demonstrates that CSM credi-

bility increases the companys ability to persuade consumers

to perform the prosocial behavior promoted in its CSM ini-

tiative. To the best of our knowledge, although the literature

exists to support the persuasiveness of individual credible

sources (e.g., Kelman 1958; Maddux and Rogers 1980; Mills

and Harvey 1972) and the effect of corporate credibility on

business outcomes (Goldberg and Hartwick 1990; Gold-

smith et al. 2000; MacKenzie and Lutz 1989), this article is

the rst to propose the linkage between corporate credibility

and consumer voluntary behavior. Moreover, building upon

Kelmans (1958, 1961, 2006) theory of internalization, we

explain that value congruence plays a key role in establishing

the relationship between CSM credibility and prosocial

behavior. While previous studies on corporate credibility

(e.g., Goldsmith et al. 2000) mainly examined the effects of

Effects of CSM on Consumer Behavior 629

1 3

attitudinal variables (e.g., attitude toward the ad) on the

credibilitybehavior relationship, our focus on value con-

gruence allows scholars to understand this relationship from

a novel and theoretically sound perspective.

Third, this framework provides an insight into how CSR

activities can simultaneously generate social and corporate

benets, an emerging research question in the business lit-

erature (Du et al. 2008; Lichtenstein et al. 2004; Porter and

Kramer 2006). As one of the rst studies addressing this

question, Lichtenstein et al. (2004) investigated whether

customer-corporate identication would mediate the effect

of CSR on both corporate benets (e.g., store loyalty) and

social benets (i.e., consumer donations to company-sup-

ported nonprot organizations). While the researchers

found a clear linkage among CSR, identication, and cor-

porate benets, their ndings about the mediation of iden-

tication in the relationship between CSR and social

benets were inconclusive, in that CSR increased customer

donations through the mediation of identication but also

had a direct negative effect on the behavior (Lichtenstein

et al. 2004). Given this mixed support for the role of iden-

tication, our framework, which is closely aligned with

Kelmans (1958, 1961, 2006) internalization perspective,

provides an alternative view by proposing the linkage

among CSM credibility, value congruence, and consumer

behavior with respect to both social and business returns.

Overall, this article contributes to the business literature

by identifying the role of corporate credibility in deter-

mining the effectiveness of CSM initiatives. Moreover, this

study, as well as future endeavors, helps companies

achieve their social and corporate goals in a simultaneous

manner, which ideally can lead to positive social change.

Research Implications

Our conceptual framework provides a number of important

propositions that require further empirical scrutiny. First,

future research should test whether each identied ante-

cedent has an effect on CSM credibility using some type of

experimental design. Previous studies examining the

antecedents of corporate credibility and other related con-

structs commonly adopted scenario-based manipulations

(e.g., Becker-Olsen et al. 2006; Keller and Aaker 1998). In

addition, although it may require more efforts, eld

experiments that compare different CSM programs char-

acterized with different levels of a given attribute (e.g.,

high effort initiative vs. low effort initiative) should

increase the external validity of the results. However, one

issue in using experimental design is that as the design

involves the manipulation of each antecedent, multiple

independent studies will be required to test the effects of all

antecedents identied. Given this, an alternative research

design is to conduct a eld survey of an actual CSM

program designed to assess consumer evaluations of the

program in terms of several attributes and CSM credibility,

as conducted by Du et al. (2008). Along with the ability to

assess multiple antecedents at the same time, this design

allows for the comparison of effect sizes across anteced-

ents, leading to the identication of more inuential ante-

cedents among others. However, as with any type of survey

research, this design has a major limitation in terms of its

inability to infer causality from the obtained results.

Future studies can also investigate the mediating effects

of value congruence on the relationship between CSM

credibility and the intended prosocial behavior as well as

customer loyalty. In line with previous research on corpo-

rate credibility (Goldberg and Hartwick 1990; Lafferty and

Goldsmith 1999), one way to undertake this investigation is

to conduct an experimental study that manipulates a com-

panys CSM credibility into different levels in ctitious

scenarios (e.g., high vs. low credibility). Alternatively, a

eld survey can be conducted to measure consumers per-

ception of a companys CSM credibility and examine its

relationships with value congruence and the two conse-

quences. However, both designs may face a common

challenge in the measurement of value congruence. In

particular, while social psychology researchers have

developed different measures of value congruence, no

optimal measurement has yet to be available (Cable and

Edwards 2004; Kristof 1996; Kristof-Brown et al. 2005).

Researchers will therefore need to carefully decide on how

to measure this construct before implementing their studies.

Furthermore, while our framework posits that all attri-

butes directly inuence CSM credibility, structural rela-

tionships may exist among attributes within the same

categories as well as across the categories. For the former

case, Rifon et al. (2004) showed that company-cause t

could indirectly inuence corporate credibility through the

mediation of corporate motives. For the latter, some

empirical evidence exists to suggest that CSM and cause

attributes signicantly affect the two types of corporate

associations (Becker-Olsen et al. 2006; Grau and Folse

2007). Given this, it may be that the two corporate attri-

butes function as mediators that transmit the effects of

some attributes in the other two categories to CSM credi-

bility. While the specication of these relationships

exceeds the scope of this article, it can provide promising

research opportunities for future work.

Managerial Implications

The framework informs managers how a company can gain

high credibility in CSM involvement. In particular, man-

agers need to ensure that the company maintains positive

image in its products and/or services, and further inform

consumers that it engages in various social activities along

630 Y. Inoue, A. Kent

1 3

with the CSM initiative. In addition, in launching a new

CSM program, it is critical for managers to proactively

initiate the program rather than in response to pressures

from the companys stakeholders. Moreover, managers

need to design CSM communication by featuring such

areas as the amount of efforts the company puts into the

program, potential, and actual benets accrued from the

performance of promoted prosocial behavior, altruistic

motives behind CSM involvement, and management and/or

employees that are personally involved in or affected by

the supported cause. In addition, when selecting which

causes the company supports in CSM, managers must

consider whether (1) the cause is important and familiar to

the consumers targeted at the initiative, (2) the cause is

relevant for local communities in which the company

operates, and (3) the support of the cause is congruent with

the companys operations and products.

Furthermore, this framework tells managers that main-

taining high credibility in CSM involvement helps the

company achieve both social and business goals. Speci-

cally, while a more prevalent view is that the creation of

social benets often conicts with the creation of corporate

benets (Porter and Kramer 2006), this framework demon-

strates that high CSMcredibility results in the adoption of the

intended prosocial behavior and enhanced customer loyalty,

generating both benets. In addition, given that the two

outcomes are closely connected with the antecedents of CSM

credibility, there may be positive feedback loops, such that

the creation of both outcomes increases positive consumer

perceptions about the company and its CSM initiative (i.e.,

customer loyalty may inuence consumer perceptions of

corporate attributes; the adoption of prosocial behavior may

affect consumer perceptions of CSM attributes). In turn, the

enhanced evaluation of the antecedents among consumers

eventually reinforces the two consequences.

In short, the current framework provides managers with

further insight into how and why the company can generate

social and corporate benets through CSM. Moreover,

given that CSM is clearly linked to the concept of CSR

(Carroll 1979, 1991) and has some connection to the eth-

ical responsibility of business based on the principle of

utilitarianism (Schwartz and Carroll 2003), the successful

implementation of CSM initiatives guided by our frame-

work would help managers fulll these two responsibilities

of their corporations.

References

Andreasen, A. R. (2004). A social marketing approach to changing

mental health practices directed at youth and adolescents. Health

Marketing Quarterly, 21(4), 5175.

Barone, M. J., Miyazaki, A. D., & Taylor, K. A. (2000). The inuence

of cause-related marketing on consumer choice: Does one good

turn deserve another? Journal of the Academy of Marketing

Science, 28, 248262.

Basil, D. Z., & Herr, P. M. (2003). Dangerous donations? The effects

of cause-related marketing on charity attitude. Journal of

Nonprot & Public Sector Marketing, 11(1), 5976.

Basil, D. Z., & Herr, P. M. (2006). Attitudinal balance and cause-

related marketing: An empirical application of balance theory.

Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 391493.

Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, A., & Hill, R. P. (2006). The impact

of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behav-

ior. Journal of Business Research, 59, 4653.

Bendapudi, N., Singh, S., & Bendapudi, V. (1996). Enhancing helping

behavior: An integrative framework for promotion planning.

Journal of Marketing, 60(3), 3349.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2003). Consumercompany identi-

cation: A framework for understating consumers relationships

with companies. Journal of Marketing, 67, 7688.

Bloom, P. N., Hussein, P. Y., & Szykman, L. R. (1997). The benets

of corporate social marketing initiatives. In M. E. Goldberg, M.

Fishbein, & S. E. Middlestadt (Eds.), Social marketing: Theo-

retical and practical perspectives (pp. 313331). Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Brown, T. J. (1998). Corporate associations in marketing: Antecedents

and consequences. Corporate Reputation Review, 1, 215233.

Brown, T., & Dacin, P. (1997). The company and the product:

Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal

of Marketing, 61(1), 6884.

Cable, D., & Edwards, J. (2004). Complementary and supplementary

t: A theoretical and empirical integration. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 89(5), 822834.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional model of corporate social

performance. Academy of Management Review, 4, 497505.

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility:

Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders.

Business Horizons, 34, 3948.

Carroll, A. B., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2012). Business and society:

Ethics, sustainability, and stakeholder management (8th ed.).

Independence, KY: Cengage Learning.

Chatman, J. (1989). Improving interactional organizational research:

A model of person-organization t. Academy of Management

Review, 14(3), 333349.

Craig, S. C., &McCann, J. M. (1978). Assessing communication effects

on energy conservation. Journal of Consumer Research, 5, 8288.

de Ruyter, K., & Wetzels, M. (2000). The role of corporate image and

extension similarity in service brand extensions. Journal of

Economic Psychology, 21, 639659.

Du, S., Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2008). Exploring the social

and business returns of a corporate oral health initiative aimed at

disadvantaged Hispanic families. Journal of Consumer

Research, 35, 483494.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2009). Strengthening

consumer relationships through corporate social responsibility.

Working paper, Simmons College School of Management.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C., & Sen, S. (2010). Maximizing business

returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR

communication. International Journal of Management Reviews,

12(1), 819.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1998). Attitude structure and function.

In D. T. Gillbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook

of social psychology (4th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 269322). New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Edwards, J. R., & Cable, D. M. (2009). The value of value

congruence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 654677.

Ellen, P. S., Mohr, L. A., & Webb, D. J. (2000). Charitable programs

and the retailer: Do they mix? Journal of Retailing, 76(3),

393406.

Effects of CSM on Consumer Behavior 631

1 3

Ellen, P. S., Webb, D. J., & Mor, L. A. (2006). Building corporate

associations: Corporate attributions for corporate socially

responsible programs. Journal of the Academy of Marketing

Science, 34, 147157.

Evanschitzky, H., & Wunderlich, M. (2006). An examination of

moderator effects in the four-stage loyalty model. Journal of

Service Research, 8(4), 330345.

Fombelle, P. W., Jarvis, C. B., Ward, J., & Ostrom, L. (2012).

Leveraging customers multiple identities: Identity synergy as a

driver of organizational identication. Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science, 40, 587604.

Fombrun, C. J. (1996). Reputation: Realizing value from the

corporate image. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Goldberg, M., & Hartwick, J. (1990). The effects of advertiser

reputation and extremity of advertising claim on advertising

effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Research, 17(2), 172179.

Goldsmith, R. E., Lafferty, B., & Newell, S. (2000). The impact of

corporate credibility and celebrity credibility on consumer

reaction to advertisements and brands. Journal of Advertising,

29(3), 4354.

Grau, S. L., & Folse, J. A. (2007). Cause-related marketing (CRM):

The inuence of donation proximity and message-framing cues

on the less-involved consumer. Journal of Adverting, 36, 1933.

Haley, E. (1996). Exploring the construct of organization as source:

Consumers understanding of organizational sponsorship of

advocacy advertising. Journal of Advertising, 25(2), 1935.

Homburg, C., Muller, M., & Klarmann, M. (2011). When does

salespeoples customer orientation lead to customer loyalty? The

differential effects of relational and functional customer orien-

tation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39,

795812.

Hovland C., & Weiss, W. (19511952). The inuence of source

credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opinion

Quarterly, 15:635650.

Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H. (1953). Communications

and persuasion: Psychological studies in opinion change. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Keller, K. L., & Aaker, D. A. (1998). The impact of corporate

marketing on a companys brand extensions. Corporate Repu-

tation Review, 1, 356378.

Keller, P., & Lehmann, D. (2008). Designing effective health

communications: A meta-analysis. Journal of Public Policy

and Marketing, 27(2), 117130.

Kelman, H. C. (1958). Compliance, identication, and internalization:

Three processes of attitude change. The Journal of Conict

Resolution, 2(1), 5160.

Kelman, H. C. (1961). Process of opinion change. Public Opinion

Quarterly, 25, 5778.

Kelman, H. C. (2006). Interests, relationships, identities: Three

central issues for individuals and groups in negotiating their

social environment. Annual Review of Psychology, 57(1), 126.

Kelman, H. C., & Hovland, C. (1953). Reinstatement of the

communicator in delayed measurement of opinion change. The

Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 48(3), 327335.

Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (2005a). Corporate social responsibility: Doing

the most good for your company and your cause. Hoboken, NJ:

Wiley.

Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (2005b). Best of breed: When it comes to

gaining a market edge while supporting a social cause,

corporate social marketing leads the pack. Social Marketing

Quarterly, 11(3), 91103.

Kotler, P., & Zaltman, G. (1971). Social marketing: An approach to

planned social change. Journal of Marketing, 35, 312.

Kotler, P., Roberto, N., & Lee, N. (2002). Social marketing:

Improving the quality of life (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA:

SAGE.

Kristof, A. (1996). Person-organization t: An integrative review of

its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Person-

nel Psychology, 49(1), 149.

Kristof-Brown, A., Zimmerman, R., & Johnson, E. (2005). Conse-

quences of individuals t at work: A meta-analysis of person-

job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor

t. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281342.

Lafferty, B., & Goldsmith, R. E. (1999). Corporate credibilitys role

in consumers attitudes and purchase intentions when a high

versus a low credibility endorser is used in the ad. Journal of

Business Research, 44(2), 109116.

Lafferty, B., Goldsmith, R. E., & Hult, G. T. M. (2004). The impact of

the alliance on the partners: A look at cause-brand alliance.

Psychology and Marketing, 21(7), 509531.

Lichtenstein, D. R., Drumwright, M. E., & Braig, B. M. (2004). The

effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to

corporate-supported nonprots. Journal of Marketing, 68, 1632.

MacKenzie, S. B., & Lutz, R. J. (1989). An empirical examination of

the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an

advertising pretesting context. Journal of Marketing, 53, 4865.

Maddux, J., & Rogers, R. (1980). Effects of source expertness,

physical attractiveness, and supporting arguments on persuasion:

A case of brains over beauty. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 39(2), 235244.

Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O. C. (2004). Corporate social responsibility

and marketing: An integrative framework. Journal of the

Academy of Marketing Science, 32, 319.

Marin, L., & Ruiz, S. (2007). I need you too! Corporate identity

attractiveness for consumers and the role of social responsibility.

Journal of Business Ethics, 71, 245260.

McCracken, G. (1989). Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural

foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of Consumer

Research, 16, 310321.

McKenzie-Mohr, D., & Smith, W. (1999). Fostering sustainable

behavior: An introduction to community-based social marketing.

Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

Menon, S., & Kahn, B. E. (2003). Corporate sponsorships of

philanthropic activities: When do they impact perception of

sponsor brand? Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(3),

316327.

Mills, J., & Harvey, J. (1972). Opinion change as a function of when

information about the communicator is received and whether he

is attractive or expert. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 21(1), 5255.

Nadler, D., & Tushman, M. (1980). A model for diagnosing

organizational behavior. Organizational Dynamics, 9(2), 3551.

Newell, S., & Goldsmith, R. E. (1998). The effect of misleading

environmental claims on consumer perceptions of advertise-

ments. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 6(2), 48.

Newell, S. J., & Goldsmith, R. E. (2001). The development of a scale

to measure perceived corporate credibility. Journal of Business

Research, 52, 235247.

Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure

celebrity endorsers perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and

attractiveness. Journal of Advertising, 19(3), 3952.

Peloza, J., & Shang, J. (2011). How can corporate social responsi-

bility activities create value for stakeholders? A systematic

review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39,

117135.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1981). Attitudes and persuasion:

Classic and contemporary approaches. Dubuque, IA: Wm.

C. Brown.

Petty, R. E., & Wegener, D. (1998). Attitude change: Multiple roles

for persuasion variables. In D. T. Gillbert, S. T. Fiske, & G.

Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., Vol.

1, pp. 323389). New York: McGraw-Hill.

632 Y. Inoue, A. Kent

1 3

Pornpitakpan, C. (2004). The persuasiveness of source credibility: A

critical review of ve decades evidence. Journal of Applied

Social Psychology, 34(2), 243281.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). Strategy and society: The link

between competitive advantage and corporate social responsi-

bility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 7892.

Reed, A., I. I., Aquino, K., & Levy, E. (2007). Moral identity and

judgments of charitable behaviors. Journal of Marketing, 71,

178193.

Rifon, N. J., Choi, S. M., Trimble, C. S., &Hairong, L. (2004). Congruence

effects in sponsorship. Journal of Advertising, 33, 2942.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of

values: Theory and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna

(Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25,

pp. 165). New York: Academic Press.

Schwartz, M. S., & Carroll, A. B. (2003). Corporate social

responsibility: A three-domain approach. Business Ethics Quar-

terly, 13, 503530.

Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to

doing better? Consumer relations to corporate social responsi-

bility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 225243.

Sen, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Korschun, D. (2006). The role of

corporate social responsibility in strengthening multiple stake-

holder relationships: A eld experiment. Journal of the Academy

of Marketing Science, 34, 158166.

Simmons, C., & Becker-Olsen, K. (2006). Achieving marketing

objectives through social sponsorships. Journal of Marketing,

70(4), 154169.

Speed, R., & Thompson, P. (2000). Determinants of sports sponsor-

ship response. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,

28(2), 227238.

Stead, M., Gordon, R., Angus, K., & McDermott, L. (2007). A

systematic review of social marketing effectiveness. Health

Education, 107, 126191.

Vlachos, P. A., Tsamakos, A., Vrecopoulos, A. P., & Avramidis, P. A.

(2009). Corporate social responsibility: Attributions, loyalty and

the mediating role of trust. Journal of the Academy of Marketing

Science, 37, 170180.

Walker, M., & Kent, A. (2012). The roles of credibility and social

consciousness in the corporate philanthropyconsumer behavior

relationship. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-

1472-6.

Yoon, Y., Gurhan-Canli, Z., & Bozok, B. (2006). Drawing inferences

about others on the basis of corporate association. Journal of the

Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 167173.

Zang, J., & Bloemer, J. M. M. (2008). The impact of value

congruence on consumer-service brand relationships. Journal of

Service Research, 11, 161179.

Effects of CSM on Consumer Behavior 633

1 3

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Environmental Values of Potential Ectourist Segmentation ProcessDocument24 pagesThe Environmental Values of Potential Ectourist Segmentation ProcessalzghoulNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- At The Nexus of Leisure and Event StudiesDocument14 pagesAt The Nexus of Leisure and Event StudiesalzghoulNo ratings yet

- Green Events Value PerceptionsDocument23 pagesGreen Events Value PerceptionsalzghoulNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Network Analysis of Tourism Events An Approach To Improve Marketing Practices For Sustainable TourismDocument15 pagesNetwork Analysis of Tourism Events An Approach To Improve Marketing Practices For Sustainable TourismalzghoulNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Tourism Value Chain Governance Review and ProspectsDocument15 pagesTourism Value Chain Governance Review and ProspectsalzghoulNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Sustainable Tourism Marketing at ADocument13 pagesSustainable Tourism Marketing at AalzghoulNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Traditions of Sustainability in Tourism StudiesDocument20 pagesTraditions of Sustainability in Tourism Studiesalzghoul0% (1)