Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Synonym: Cocos Nucifera Linn

Uploaded by

Yovano TiwowOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Synonym: Cocos Nucifera Linn

Uploaded by

Yovano TiwowCopyright:

Available Formats

Cocos nucifera Linn.

SYNONYM

Palma cocos Mill. COMMON NAME

Coconut, nyog BOTANICAL DESCRIPTION

Persley (1992) reported that two main groups of coconut trees, the Tall (Typica) and the Dwarf (Nana) types, are

known. Early Spanish explorers called it coco, which means "monkey face" because of the 3 indentations (eyes)

on the hairy nut resemble the head and face of a monkey. Nucifera means "nut-bearing".

Ross (2005) described Cocos nucifera as an unbranched monoecious plant of the Arecaceae family. It grows to

30 m tall, with a crown of 25-35 paripinnate leaves, producing 12-16 new leaves per year. There is a central bud

which if cut off, leads to the death of the tree. The adventitious roots arise from the base of the trunk. The trunk is

straight or gently curved, with marked foliar scars, 3050 cm in diameter, rises from a thickened base and

increases in height at a decreasing rate with age. The leaves are hanging horizontally, 4-8 m in length and

divided. Segments of leaves are numerous, linear-lancelate, 0.5-1 m long and tapering. In the axil of each leaf is

a spathe enclosing a long, stout, straw or an orange-colored spadix. The spadix is composed of up to 40

branches, each bearing up to 300 small, male flowers and a few female, 2 cm long, globose flowers. The male

and female flowers are produced separately in the leaf axils, usually on a long stalk. Approximately one-third of

the female flowers develop into 4-8 ripe fruits in 12-13 months, per inflorescence. The fruit is ovoid, three-angled

drupe, up to 30 cm long, usually with thick, fibrous mesocarp (husk) and a hard, green-brown endocarp (shell)

enclosing one seed. The seeds consists of 10-20 mm-thick white, fleshy endosperm (meat), covered by thin

brown testa, surrounding a cavity party filled wiih a watery, sweet fluid (coconut water) that reduces as the fruit

ripens.

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION

Persley (1992) reported that coconut is the most widely naturally distributed palm tree. It is extensively cultivated

around the world and is considered to be one of the most important tropical species used by man. Southeastern

Asia is believed to be the center of origin of the species due to the great morphological variability, the large

number of popular/local names and plant uses, and the number of associated insects in that region. The major

coconut areas lie between 20N and 20S of the equator. It has been suggested that the spreading of the species

throughout diverse regions of the world occurred naturally, carried by oceanic currents from Southeast Asia to the

Pacific and Indian oceans and by human migration during the colonization of Asia and America. The introduction

of the species from the Atlantic coast of Africa to America occurred after the discovery of the Cape of Good Hope

Purseglove (1975) during the period of extensive mercantile navigation in the 16th century. Quisumbing (1978)

reported that coconut is very extensively cultivated in the Philippines and especially in those regions where the

dry season is not too prolonged, up to 800 m above sea level, on humus-rich and porous soil or pure sand in

coastal region, reported by Ross (2005). It was introduced in the Philippines during prehistoric times.

ETHNOPHARMACOLOGICAL USES

Uses in Philippine traditional medicine

Quintana and Saraos (1982) reported a myriad of uses of coconut based on a nationwide survey of traditional

healers. Parts of the coconut plant used include the roots, bark of tree, leaves, fruits, coconut water, coconut

meat and oil. The uses include itchiness, eczema, burns, wounds, dandruff and falling hair; as well as for urinary

problems, edema, diarrhea, ulcer, dysmenorrhea! and hemorrhoids. The oil is much used in the Philippines as a

vehicle for liniments in skin medicines and for other external applications. It is also used for strengthening the hair

hence used with gogo to make a shampoo.

The tuba, or toddy, when drawn early in the morning and drunk immediately is stimulating and acts as a mild

laxative but excessive use is harmful to the health. A toddy-poultice (fresh toddy and rice flour) is a valuable

application on gangrenous ulcerations, indolent ulcers, and carbuncles.

Uses in other traditional medical systems

The decoction of Cocos nucifera L. husk fiber has been used in northeastern Brazil traditional medicine for

treatment of diarrhea and arthritis.

Quisumbing (1978) mentions different medicinal uses of roots. They are astringent and are used in Java for

dysentery and other intestinal complaints while they are used for cough in Amboina. Malays use a poultice of the

roots in syphilis and gonorrhea and in rheumatism. They are also used for strengthening the gum and a

decoction of ground roots is drunk in cases of smallpox. There are also reports that the roots are antiscorbutic

and diuretic. In India the young roots are employed as an astringent gargle for sore throat and when boiled with

ginger and salt, they are efficacious in fevers. The ash of the bark is used as a dentrifice and an antiseptic and is

also prescribed in scabies. The soft, downy, light brown colored substance found on the lower surface of the

leaves is considered a good styptic. The oil is used as a local application in alopecia. The use of the bark in the

Gold Coast for curing toothache and earache. The flowers are reported as astringent and are chewed in the

immature state for gonorrhea and in Sanskrit are recommended for diabetes, dysentery, leprosy, and urinary

discharges. The cocomilk, which is the product of the expressed juice of the grated endosperm is prescribed in

debility, incipient pthisis and cachetic affections. In large doses it proves aperients and actively purgative. In India

it is useful in allying urinary irritation and in Brazil is applied as a lotion to ulcers of the penis.

PHARMACOGNOSY

The refractive and the FTIR spectra of virgin coconut oil and virgin olive oil were successfully measured at room

temperature. The refractive index was measured in the spectral range of 400-700 nm while the FTIR measurement

was covered in the range of 600-4000 cm?l. All the experimental data were fitted to the Cauchy formula to obtain the

Cauchy constantsand it was found that the refractive index and the Cauchy constants, A, B and C of virgin olive oil are

higher then the one obtained for virgin coconut oil, except for the sample density. The FTIR spectra shows that the

five important peaks explaining the stretchingabsorption due to aldehyde (C = O) and esters (C-O), bending

absorption (methylene (CH2) and methyl (CH3) groups) and double bond absorptions (C = O) are strong in virgin

olive oil than in the virgin coconut oil samples. (Yunus, 2009)

The oxidative stability of virgin coconut oil in deep fat frying at 185+5C for a total of 30 hours was evaluated and

compared with that of similarly-treated palm olein based on changes in the peroxide value, p-anisidine value, total

oxidation value, total polar compound content and color. Results show that there was a significant increase (pms. Acid

and rancid aromas were likewise highly correlated (R2=0.90) as the acidic notes perceived may contribute to the

overall rancid characteristics of the coconut oil samples. (Villarino, 2007)

PHYTOCHEMISTRY

TOXICOLOGY

Coconut oil is listed as Generally Recognized as Safe by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, is listed on the

Everything Added to Food in the United States list, and has received a Select Committee on Generally

Recognized as Safe Substances Type 1 rating, meaning that there is no evidence in the available information on

coconut oil that demonstrates or suggests reasonable grounds to suspect, a hazard to the public when used at

levels that are now current or might reasonably be expected in the future. Doses are based on those most

commonly used in available trials or in historical practice. However, with natural products it is often not clear what

the optimal doses are to balance efficacy and safety. Preparation of products may vary from manufacturer to

manufacturer, and from batch to batch within one manufacturer. Because it is often not clear what the active

component of a product is, standardization may not be possible, and the clinical effects of different brands may

not be comparable.

Acute toxicity

In an acute toxicity study by Pekson (2007), VCO at a dose of 5000 mg/kg caused neither visible signs of toxicity

nor mortality. All five rats were healthy throughout the experiment and survived until the end of observation

period. The LD50 of virgin coconut oil was determined to be greater than 36.7 g/kg in mice, with no adverse

effect level (NOAEL) at 2.3 g/kg. Reversible acute toxidrome consisted of oily stool and blood-streaked feces.

Sub-acute administration of virgin coconut oil was associated with dose-dependent elevation of serum

triglycerides, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, AST and ALT. Fasting blood sugar was reduced at low to medium

doses of virgin coconut oil, while an increase in fasting blood sugar was observed at high dose (6.3 g/kg). Virgin

coconut oil was potentially hepatotoxic and nephrotoxic at medium (4.14 g/kg) and high doses (6.3 g/kg) in rats.

Sub-chronic toxicity

Pekson (2007) reported in sub-chronic toxicity study, that administration of the virgin coconut oil at 175, 550 and

2000 mg/kg for 28 days did not produce any mortality and there were no significant differences in the general

condition, growth, organ weights, hematological parameters, clinical chemistry values, or gross and microscopic

appearance of the organs from the treatment groups as compared to the control group. The LD50 for the virgin

coconut oil is found to be more than 5000 mg/kg body weight whereas, the observed adverse effect level was

found to be 2000 mg/kg per day for 28 days.

Developmental and reproductive toxicity

Francois (1998) reported that lauric acid from coconut oil has been shown to be excreted in breast milk 6 hours

after consumption of a diet containing the fatty acid and remained elevated in milk for 10-24 hours.

BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITY

Analgesic

The use of virgin coconut oil is relatively safe and well tolerated coupling medium in therapeutic ultrasound. Virgin

coconut oil was shown to be seemingly more effective as mineral oil in terms of the reduction of pain and more

effective in improvement of flexion and extension range of motion of affected joint.

Endocrine/Metabolic

Coconut has been shown to provide adequate nutrition to infants; however, since coconut was not administered

alone in any trial, the effects of coconut cannot be fully elucidated. Therefore, until trials employing coconut oil

alone are conducted, there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the use of coconut oil for infant

nutrition.

Coconut flour has been shown to decrease the glycemic index of various baked goods and may be helpful in

controlling diabetes. However, until trials with large sample sizes are conducted, there is insufficient evidence to

recommend for or against the use of coconut in treating diabetes mellitus.

Virgin coconut oil significantly increases fasting blood sugar and decreases high density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Virgin coconut oil also increases creatinine and platelet count and decreases white blood cell count. Mild

gastrointestinal complaints were the most commonly reported adverse events. Further studies may be needed in

order to validate the results of this exploratory study and elucidate the metabolic effects of virgin coconut oil.

Virgin coconut oil is a cheap oil source containing high concentration of medium chain fatty acids which had

shown beneficial effect in waist circumference reduction especially in males without any deleterious effect to the

lipid profile.

Gastrointestinal/ Digestive

A milk-free formulation containing coconut has been shown to shorten the average duration of diarrhea in

children with mild symptoms in one randomized study. However, although these results seem promising, until

trials with large sample sizes are conducted, there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the use of

coconut in treating diarrhea. Adams et al. conducted a clinical trial to determine the effectiveness of coconut

water in children with mild diarrhea. Young coconut water can be used, together with early refeeding, as a home

glucose electrolyte oral rehydration solution in the early stages of mild diarrhea, despite not having a balanced

electrolyte

composition. However, young coconut water should not be used in patients with severe cholera, or in patients

who are dehydrated or in whom renal function is impaired.

Cardiovascular/Circulatory

Coconut has been shown to decrease cholesterol levels in clinical trials. In one randomized, double-blinded

crossover trial, consumption of coconut flakes reduced serum total and LDL cholesterol and serum triglycerides

in subjects with moderately high cholesterol levels. However, since coconut was administered alone in very few

trials, the effects of coconut cannot be fully elucidated. Therefore, until trials employing coconut oil alone are

conducted, there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the use of coconut for

hypercholesterolemia.

Coconut has been shown to decrease both systolic and diastolic blood pressure in a controlled comparative trial.

However, although these results are promising, until randomized trials with large sample sizes are conducted,

there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the use of coconut in treating hypertension.

Dermatologic

Coconut oil was shown to be a comparable moisturizer to mineral oil in individuals with dry skin in a randomized,

controlled, double-blinded trial. However, until trials with large sample sizes are conducted, there is insufficient

evidence to recommend for or against the use of coconut in treating dry skin.

Coconut oil showed no significant effects as a potential emollient prior to photochemotherapy or narrow band

UVB (311-313 nm) phototherapy for psoriasis. However until more trials with large sample sizes are conducted,

there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the use of coconut in treating psoriasis.

Topical application of virgin coconut oil had a protective effect on the development of striae gravidarum although

it did not significantly decrease the incidence of development of striae gravidarum.

Pediculicide

A remedy consisting of coconut oil, anise oil and ylang ylang oil was as effective in controlling louse infestation as

a traditional lice treatment. However since coconut oil was used in combination with ether oils, its effects on louse

infestation cannot be fully elucidated. Therefore, until more trials with large sample sizes are conducted, there is

insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the use of coconut in treating louse infestation.

Antifungal

In vitro research of Ogbolu (2007), shows that virgin coconut oil was effective as an antifungal agent against

some species of Candida, particularly Candida albicans, which had the highest susceptibility to coconut oil

(100%), with a minimum inhibitory concentration of 25% (1:4 dilution).

Virgin coconut oil can be used as beneficial alternative treatment for diaper dermatitis among pediatric patients

as it is efficacious, safe and less expensive.

PHARMACOPHYSIOLOGIC EFFECTS

PHARMACOKINETICS

CLINICAL STUDIES

Phase 1

Sankaranarayanan (2005) conducted a randomized controlled trial to examine the effects of massage with

coconut oil on growth velocity and neurobehavioral development in full-term and preterm neonates. Preterm

neonates weighing 1,500-2,000 g full-term births weighing more than 2,500 g were randomized to receive

massage with coconut oil, mineral oil or placebo 4 times daily. Outcome measures included weight gain velocity

and neurobehavioral development, as measured by the Brazelton Score. Massage with coconut oil resulted in

significantly greater weight gain velocity when compared to mineral oil and placebo in preterm neonates and

compared to placebo in full-term babies. No statistically significant difference in neurobehavioral development

was observed between any of the groups.

Rey Matias (2011) conducted a randomized controlled double blinded study in an industrial out-patient clinic in Pasig

City. The outcome measures were change in pain scores using the numerical rating scale and change in flexion and

extension range of motion of involved joints using goniometric measurement from baseline to second follow-up and

third follow-up. Repeated measures ANOVA showed that there were reductions in the pain scores by visits. There

were no reported adverse effects from the use of virgin coconut oil and mineral oil, physical therapy program and pain

medications in both groups.

Trinidad (2003) conducted a randomized controlled trial to determine the glycemic index of commonly consumed

bakery products supplemented with increasing levels of coconut flour for proper control and management of diabetes

mellitus (32The authors concluded that the fat content of coconut flour-supplemented food should be considered to

optimize the functionality of coconut fiber in the proper control and management of diabetes mellitus.

Nelson (1998) conducted a randomized crossover trial to compare the absorption of fat and calcium by infants fed a

formula containing a blend of palm olein (53%) and soy oil (47%) with that by infants fed a formula containing a

blend of soy oil (60%) and coconut oil (40%). The authors concluded that fat is less well absorbed from a mixture of

53% palm olein and 47% soy oil than from a mixture of 60% soy oil and 40% coconut oil, and that absorption of

calcium is less from a formula containing palm olein, presumably because of the formation of insoluble calcium soaps

of unabsorbed palmitic acid.

Hayes (1992) conducted a clinical trial to examine the effect of breastfeeding compared with two fat-modified milk

formulas, one of which was a saturated fat formula with coconut oil and soybean oil (8). The presence of cholesterol

in human milk appeared to expand the low density lipoprotein ratio. Thus modulation of infant liporpoteins by

changing dietary fat and cholesterol is feasible and in keeping with the known response in adults.

Antebi (2004) conducted a randomized, double-blinded study to determine the efficacy and safety of an alpha-

tocopherol-enriched emulsion incorporating soybean, coconut, olive and fish oils on measures of liver function. There

was a significant improvement in plasma lipophilic antioxidant vitamins and low density lipoprotein alpha-tocopherol

levels only in the soybean, coconut, olive and fish oil group. The lower increase of plasma liver enzymes and the

phospholipids:apolipoprotein Al ratio in the soybean, coconut, olive and fish oil group suggest a better liver function

than in the soy bean oil based emulsion group.

Sabitha (2009) compared the lipid profile and antioxidant enzymes of normal and diabetic subjects consuming two

different types of oil as cooking medium. Total glutathione and glutathione peroxidase values showed significant

decrease in diabetic subjects as compared to the controls, while superoxide dismutase values showed significant

difference between coconut oil consuming groups. Though lipid profile parameters and oxidative stress were high in

Type 2 diabetic subjects compared to controls, no pronounced changes for these parameters were observed between

the subgroups (coconut oil versus sunflower oil).

Liau (2011) conducted an open-label pilot study on four weeks of virgin coconut oil to investigate its efficacy in weight

reduction and its safety of use in 20 obese but healthy Malay volunteers. There was no change in the lipid profile.

There was a small reduction in creatinine and alanine transferase levels. Virgin coconut oil is efficacious for waist

circumference reduction especially in males and it is safe for use in humans. There were some limitations to this

study. There was no long term follow up on the weight, anthropometric and lipid profile in the subjects and the

duration of the virgin coconut oil intake consumption was too short.

Assuncao (2009) investigated the effects of dietary supplementation with coconut oil on the biochemical and

anthropometric profiles of women presenting waist circumferences >88 cm (abdominal obesity). The randomized,

double-blinded, clinical trial involved 40 women aged 20-40 years. Groups received daily dietary supplements

comprising 30 mL of either soy bean oil (N=20) or coconut oil (N=20) over a 12-week period, during which all

subjects were instructed to follow a balanced hypocaloric diet and to walk for 50 minutes per day. The supplements

group presented an increase (puded evidence of psoriasis clearance. No significant acceleration of psoriasis clearance

was seen in either group.

Cuya conducted a randomized controlled trial to determine the efficacy of topically applied virgin coconut oil in the

prevention of striae gravidarum. Primigravidas with singletons, seen from their first trimester to 16 weeks age

of gestation, with no medical conditions and have not applied any agents over the abdomen, were included in the

study. Subjects were randomized into treatment and non-treatment group. Those in the treatment group were

supplied with virgin coconut oil for application to the whole abdomen at bedtime daily from the start of the study to

time of delivery. Seventy-five primigravidas (41 in control and 40 in the treatment group) were evaluated striae

gravidarum developed earlier in the control group and in the younger age group.

Mumcuoglu (2002) conducted an open trial to examine the pediculicidal efficacy and safety of a natural remedy

containing coconut oil, anise oil, and ylang ylang oil. One hundred nineteen children were treated with the natural

remedy, which contained coconut oil, anise oil and ylang ylang oil, for 15 minutes, three times at five-day intervals or

a spray formulation containing permethrin, malathion, piperonyl butoxide, isododecane and propellant gas, twice for

10 minutes with a 10-day interval between applications. Outcome measures included control of louse infestation.

Louse infestation was controlled in 60 children that received the natural remedy (92.3%) and 59 that received the

control pediculicide (92.2%). There were no significant side effects associated with either formulation.

Svahn (2003) conducted a randomized controlled trial to examine differences in fatty acid content of plasma lipid

fractions and serum lipid concentrations among young children fed different milk diets. Outcome measures included

plasma fatty acids, blood lipids and apolipoproteins at 15 months of age, and dietary intakes at 12, 15 and 18 months.

The authors concluded that children fed milk with 50% or 100% vegetable fat, together with high-vegetable fat and

low-milk fat dairy products have lower percentages of plasma saturated fatty acids and higher percentages of

polyunsaturated fatty acids than children fed standard- or low-fat milk and dairy products.

Fuchs (1994) conducted a randomized trial to determine the effects of feeding regimens of varying fat composition on

dietary intake and serum lipid and lipoprotein concentrations in older infants. Mean serum total cholesterol was

significantly higher in the infants fed cow milk at age 12 months, whereas mean low density lipoprotein and

apolipoprotein B were lower in the infants fed the follow-up formulas. Infants consuming the infant formula or whole

cow milk demonstrated greater increases in mean serum total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein, and apolipoprotein

B by 12 months of age compared with infants ingesting follow up formula. Growth measurements were equivalent

among all groups.

Alleyne (2005) conducted a controlled comparative trial to examine the effects of regular consumption of two tropical

food drinks, coconut water and mauby (Colubrina arborescens), on the control of hypertension. Significant decreases

in the mean systolic blood pressure were observed for 71%, 40% and 43% for patients receiving the coconut water,

mauby and the combination of coconut and mauby, respectively, (p

RECOMMENDED USES

Adult (age > 18) Oral Dehydration

Coconut water has been used for exercise-induced dehydration.

Diabetes mellitus

Bakery products supplemented with 50-250 g of coconut flour have been studied for the management of diabetes

mellitus.

High cholesterol

Fat supplements with coconut oil delivered in oatmeal-raisin cookies have been used in combination with

lovastatin for six-week periods. Lunches and dinners with 35% fat calories, 60% of which is coconut oil (saturated

fat), were consumed for five weeks (39). Coconut oil with or without psyllium fiber have been used as part of a

controlled diet for seven-day experimental periods.

Hypertension

Coconut water has been studied for its effects controlling hypertension.

Topical Dry skin

Virgin coconut oil has been applied to the legs twice daily for two weeks.

Psoriasis

Pre-irradiation application of coconut oil on half of the body has been studied in patients with chronic plaque

psoriasis.

Children (ageuncontrolled studies have found that coconut can increase cholesterol levels, and that populations

that consume large amounts of coconut fat have higher cholesterol levels than those who do not. However, the

research is not conclusive, as coconut has also been shown to decrease serum cholesterol and low density

lipoprotein cholesterol levels in controlled human trials. Use cautiously in patients using antihypertensives, as

coconut has been shown to decrease mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure in humans and theoretically

may increase the risk of hypotension. Avoid in patients with severe cholera, according to clinical research. Avoid

in patients who are dehydrated or have impaired renal function, according to clinical research.

The set of data presented on RECOMMENDED USES is adapted from the patient monograph of the Natural

Standard.

AGRICULTURAL STUDIES

ECONOMIC STUDIES

Nour (2009) investigated the potential of centrifugation method in demulsification (emulsion breaking) of coconut milk

emulsion. The conventional methods to produce virgin coconut oil by using fermentation and cold pressing need

longer time to break these emulsions. Coconut milk from the local market was used as samples for the study. The

centrifuge speed was varied from 6000 to 12000 rpm and the centrifugation time was varied from 30 to 105 min. The

present research found that, centrifugation method can enhance the demulsification of oil-in-water coconut milk

emulsions in a very short time compared to the conventional methods. Due to its fast and higher quality of virgin

coconut oil, centrifuge can be used as an alternative demulsification method for oil-in-water coconut milk emulsions.

This method provides higher yields, quicker and less expensive.

Hamid (2011) describes the process for virgin coconut oil production through integrated wet process. The novel

features of this process is the production of virgin coconut oil itself which can minimize the time, cost, energy and

man power as well as can minimize the yield and improve the quality of coconut oil. The virgin coconut oil obtained by

this process contributes about 30-40% wt/wt of yield which is 10-20% higher than conventional method. The physical

characteristics of virgin coconut oil along this process shows that the virgin coconut oil is colorless, retain fresh

coconut aroma and sweet coconut taste with the highest content of lauric acid (49.85%). The results also indicates

the presence of vitamin E.

SOCIO-CULTURAL STUDIES

REFERENCES

Adams W and Bratt DE. Young coconut water for home rehydration in children with mild gastroenteritis. Trop

GeogrMed. 1992;44(l-2): 149-153.

Agero AL and Verallo-Rowell VM. A randomized double-blind controlled trial comparing extra virgin coconut oil

with mineral oil as a moisturizer for mild to moderate xerosis. Dermatitis. 2004;15(3):109-116.

Alleyne T, Roache S, Thomas C and Shirley A. The control of hypertension by use of coconut water and

mauby:two tropical food drinks. West Indian Med J. 2005;54(1):3-8.

Anderson JT, Grande F and Keys A. Independence of the effects of cholesterol and degree of saturation of the

fat in the diet on serum cholesterol in man. Am J Clin Nutr. 1976;29(11): 1184-1189.

Antebi H, Mansoor 0, Ferrier C, Tetegan M, Morvan C, Rangaraj J and Alcindor LG. Liver function and plasma

antioxidant status in intensive care unit patients requiring total parenteral nutrition: comparison of 2 fat emulsions.

J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2004;28(3): 142-148.

Assuncao ML, Ferreira HS, dos Santos AF, Cabral CRJr and Florencio TMMT. Effects of dietary coconut oil on

the biochemical and anthropometric profiles of women presenting abdominal obesity. Lipids. 2009;44:593-601.

Bhan MK, Arora NK, Khoshoo V, Raj P, Bhatnager S, Sazawal S and Sharma K. Comparison of a lactose-free

cereal-based formula and cow's milk in infants and children with acute gastroenteritis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol

Nutr. 1988;7(2):208-213.

Candelaria LV, Magsadia CR, Velasco RE, Pedro MR, Barbara CV and Tanchoco CC. The effect of vitamin A-

fortified coconut cooking oil on the serum retinol concentration of Filipino children 4-7 years old. Asia Pac J Clin

Nutr. 2005;14(l):43-53.

Cheah FC and Boo NY. Risk factors associated with neonatal hypothermia during cleaning of newborn infants in

labour rooms. J Trop Pediatr. 2000;461(l):46-50.

Couturier P, Basset-Stheme D, Navette N and Sainte-Laudy J.[Acase of coconut oil allergy in an

infant:responsibility of "maternalized" infant formulas]. Allerg Immunol (Paris). 1994;26(10):386-387.

Das NG, Nath DR, Baruah I, Talukdar PK, Das SC. Field evaluation of herbal mosquito repellents. J Commun

Dis. 1999;31(4):241-245.

Francois CA, Connor SL, Wander RC and Connor WE.Acute effects of dietary fatty acids on the fatty acids of

human milk. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67(2):301-308.

Fuchs GJ, Farris RP, DeWier M, Hutchinson S, Strada R and Suskind RM. Effect of dietary fat on cardiovascular

risk factor in infancy. Pediatrics. 1994;93(5):756-763.

Kamakar PR, Das A and Chatterjee BP.PIacebo-controlled immunotherapy with Cocos nucifera pollen extract. Int

Arch Allergy Immunol. 1994;103(2): 194-201.

Kumar PD. The role of coconut and coconut oil in coronary heart disease in Kerala, South India. Trop Doct.

1997;27(4):215-217.

Ganji V and Kies CV. Psyllium husk fibre supplementation to soybean and coconut oil diets of humans: effect on

fat digestibility and faecal fatty acid excretion. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994;48(8):595-597.

Ganji V and Kies CV. Psyllium husk fiber supplementation to the diets rich in soybean or coconut oil:

hypocholesterolemic effect in healthy humans. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 1996;47(2): 103-110.

George SA, Bilsland DJ, Wainwright NJ and Ferguson J. Failure of coconut oil to accelerate psoriasis clearance

in narrow-band UVB phototherapy or photochemotherapy. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128(3):301-305.

Ghazali HM, Tan A, Abdulkarim SM, Dzulkifly MH. Oxidative stability of virgin coconut oil compared with RBD

palm olein in deep-fat frying offish crackers. J Food Agriculture and Environment. 2009; 7(3-4): 23-27.

Govere J, Durrheim DN, Baker L, Hunt R and Coetzee M. Efficacy of three insect repellents against the malaria

vector Anopheles arabiensis. Med Vet Entomol. 2000; 14(4):441-444.

Hadis M, Lulu M, Mekonnen Y and Asfaw T.Field trials on the repellent activity of four plant products against

mainly Mansonia population in western Ethiopia. Phytother Res. 2003;17(3):202-205.

Hamid MA, Sarmidi MR, Mokhtar TH, Sulaiman WRW, Aziz RA. Innovative integrated wet process for virgin

coconut oil production. J App Sci. 2011;ll(13):2467-2469.

Hayes KC, Pronczuk A, Wood RA and Guy DG. Modulation of infant formula fat profile alters the low-density

lipoprotein ratio and plasma fatty acid distribution relative to those with breast-feeding. J Pediatr. 1992; 120(4 Pt

2):S109-S116).

Liau KM, Lee YY, Chen CK and Rasool AHG. An open-label pilot study to assess the efficacy and safety of virgin

coconut oil in reducing visceral adiposity. ISRN Pharmacology. 2011;EPUB AHEAD OF PRINT.

Macfarlane BJ, Bezwoda WR, Bothwell TH, Baynes RD, Bothwell JE, MacPhail AP, Lamparelli RD and Mayet F.

Inhibitory effect of nuts on iron absorption. Am J CLin Nutr. 1988;47(2):270-274.

McKenney JM, Proctor JD, Wright JTJr, Kolinski RJ, Elswick RKJr and Coaker JS. The effect of supplemental

dietary fat on plasma cholesterol levels in lovastatin-treated hypercholesterolemic patients. Pharmacotherapy.

1995; 15(5): 565-572.

Mendis S and Kumarasunderam R. The effect of daily consumption of coconut fat and soya bean fat on plasma

lipids and lipoproteins of young normolipedaemic men. Br J Nutr. 1990;63(3): 547-552.

Mumcuoglu KY, Miller J, Zamir C, Zentner G, Helbin V and Ingber A. The in vivo pediculicidal efficacy of a natural

remedy. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4(10):790-793.

Nelson SE, Frantz JA and Ziegler EE. Absorption of fat and calcium by infants fed a milk-based formula

containing palm olein. J Am Cool Nutr. 1998;17(4):327-332.

Nour AH, Mohammed FS, Yunus RM, Arman A. Demulsification of virgin coconut oil by centrifugation method: a

feasibility study. Int J Chem Tech. 2009; 1(2): 59-64.

Ogbolu DO, Oni AA, Daini OA and Oloko AP. In vitro antimicrobial properties of coconut oil on Candida species

in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Med Food. 2007; 10(2):384-387.

Pekson RC. Acute and subacute toxicity of virgin coconut oil in rodents[Thesis].Manila: University of the

Philippines;2007.

Persley G.J. Replanting the Tree of Life: Toward an International Agenda for Coconut Palm Research.

Wallingford: CAB/ACIAR; 1992.

Prior IA, Davidson F, Salmond CE and Czochanska Z. Cholesterol, coconuts and diet on Polynesian atolls:a

natural experiment: the Pukapuka and Tokelau island studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34(8): 1552-1561.

Quisumbing E. Medicinal Plants of the Philippines. Quezon City, Philippines: JMC Press; 1978.

Reiser R, Probstfield JL, Silvers A, Scott LW, Shorney ML, Wood RD, O'Brien BC, Gotto AMJr and Insull WJr.

Plasma lipid and lipoprotein response of humans to beef fat, coconut oil and safflower oil. Am J Clin Nutr.

1985;42(2): 190-197.

Rey-Matias RR. Comparative effectiveness in pain alleviation, range of motion, safety and tolerability between

virgin coconut oil and minral oil as therapeutic ultrasound coupling medium among patients with

musculotendinous injuries. Act Med Phil. 2011;45(2):50-57.

Romer H, Guerra M, Pina JM, Urrestarazu MI, Garcia D and Blanco ME. Realimentation of dehydrated children

with acute diarrhea: comparison of cow's milk to a chicken-based formula. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

1991;13(1):46-51.

Rosado A, Fernandez-Rivas M, Gonzalez-Mancebo E, Leon F, Campos C and Tejedor MA. Anaphylaxis to

coconut. Allergy. 2002;57(2): 182-183.

Saat M, Singh R, Sirisinghe RG and Nawawi M. Rehydration after exercise with fresh young coconut water,

carbohydrate-electrolyte beverage and plain water. J Physiol Anthropol Appl Human Sci. 2002;21(2):93-104.

Sabitha P, Vaidyanathan K, Vasudevan DM and Kamath P. Comparison of lipid profile and antioxidant enzymes

among South Indian men consuming coconut oil and sunflower oil. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry.

2009;24(1):76-81.

Sankaranarayanan K, Mondkar JA, Chauhan MM, Mascarenhas BM, Mainkar AR and Salvi RY. Oil massage in

neonates: an open randomized controlled study of coconut versus mineral oil. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42(9):877-

884.

Sharma SK, Dua VK and Sharma VP. Field studies on the mosquito repellent action of neem oil. Southeast Asian

J Trop Med Public Health. 1995;26(1): 180-182.

Solanki K, Matnani M, Kale M, Joshi K, Bavdekar A, Bhave S and Pandit A. Transcutaneous absorption of

topically massaged oil in neonates. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42(10):998-1005.

Svahn JC, Feldl F, Raiha NC, Koletzko B and Axelsson IE. Fatty acid content of plasma lipid fractions, blood

lipids and apolipoproteins in children fed milk products containing different quantity and quality of fat. J Pediatr

Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;31(2): 152-161.

Teuber SS and Peterson WR. Systemic allergic reaction to coconut (Cocos nucifera) in 2 subjects with

hypersensitivity to tree nut and demonstration of cross-reactivity to legumin-like seed storage proteins: new

coconut and walnut food allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999; 103(6): 1180-1185.

Trinidad TP, Loyola AS, Mallillin AC, Valdez DH, Askali FC, Castillo JC, Resaba RL and Masa DB. The

cholesterol-lowering effect of coconut flakes in humans with moderately raised serum cholesterol. J Med Food.

2004; 7(2): 136-140.

Trinidad TP, Valdez DH, Loyola AS, Mallillin AC, Askali FC, Castillo JC and Masa DB. Glycemic index of different

coconut (Cocos nucifera)-flour products in normal and diabetic subjects. Br J Nutr. 2003;90(3):551-556.

Villarino BJ, Dy LM, Lizada CC. Descriptive sensory evaluation of virgin coconut oil and refined, bleached and

deodorized coconut oil. LTW-Food Sci Tech. 2007 March;40(2): 193-199.

Yunus WMM, Fen YW, Yee LM. Refractive index and fourier transform infrared spectra of virgin coconut oil and

virgin olive oil. Am J Applied Sci. 2009;6(2):328-331.

You might also like

- 101 Amazing Uses for Coconut Oil: Decrease Wrinkles, Balance Hormones, Clean a Hairbrush, and 98 More!From Everand101 Amazing Uses for Coconut Oil: Decrease Wrinkles, Balance Hormones, Clean a Hairbrush, and 98 More!No ratings yet

- Analgesic Property of Corchorus Olitorius LDocument52 pagesAnalgesic Property of Corchorus Olitorius LabdallahlotfylNo ratings yet

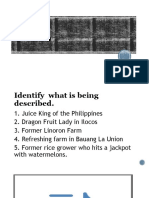

- SEMANGKADocument8 pagesSEMANGKAbayuwinotoNo ratings yet

- A Review of PiliDocument10 pagesA Review of PiliFrancine Robles100% (2)

- Coconut (Cocos Nucifera L. Arecaceae) in Health Promotion and Disease PDFDocument7 pagesCoconut (Cocos Nucifera L. Arecaceae) in Health Promotion and Disease PDFOctavio Niño OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Onuekwusi Et Al., 2014-1Document10 pagesOnuekwusi Et Al., 2014-1Cho ChoNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Benefits of Tiger Nut OilDocument85 pagesNutritional Benefits of Tiger Nut Oilshadrach bartholomewNo ratings yet

- Anacardium Occidentale 4Document11 pagesAnacardium Occidentale 4Jesus Llorente MendozaNo ratings yet

- TubangDocument9 pagesTubangRubie Carla GuimbalNo ratings yet

- Coconut's Health Benefits: Medicinal Uses Promote WellnessDocument9 pagesCoconut's Health Benefits: Medicinal Uses Promote WellnessAdit TaufikNo ratings yet

- Food Chemistry: Ibironke A. Ajayi, Rotimi A. Oderinde, Victor O. Taiwo, Emmanuel O. AgbedanaDocument8 pagesFood Chemistry: Ibironke A. Ajayi, Rotimi A. Oderinde, Victor O. Taiwo, Emmanuel O. AgbedanaIngrid DantasNo ratings yet

- Cocos Nucifera (L.) Is An Important Member of The Family Arecaceae (Palm Family) PopularlyDocument30 pagesCocos Nucifera (L.) Is An Important Member of The Family Arecaceae (Palm Family) PopularlyYiv IvesNo ratings yet

- Ijifnsa D 2 2018Document9 pagesIjifnsa D 2 2018diddyjamesNo ratings yet

- Grapefruit Peel Oil's Antimicrobial Effects Against E. coliDocument11 pagesGrapefruit Peel Oil's Antimicrobial Effects Against E. coliDiana Churata OroyaNo ratings yet

- Coconut's Health Benefits and Disease Prevention RoleDocument7 pagesCoconut's Health Benefits and Disease Prevention Rolecarla soaresNo ratings yet

- Related LiteratureDocument5 pagesRelated LiteratureJozel Anne DoñasalesNo ratings yet

- WatermelonDocument8 pagesWatermelonDania KumalasariNo ratings yet

- Metho Revised KindaDocument10 pagesMetho Revised KindaRonaldo OsumoNo ratings yet

- Antibacterial Activity of Adansonia Digitata Stem Bark Extracts On Some Clinical Bacterial IsolatesDocument7 pagesAntibacterial Activity of Adansonia Digitata Stem Bark Extracts On Some Clinical Bacterial IsolatesSami AbdelmagidNo ratings yet

- Jatropha Curcas: A Seminar PresentedDocument16 pagesJatropha Curcas: A Seminar PresentedMarshal GrahamNo ratings yet

- KanujaDocument5 pagesKanujaPradeepkumar BandaruNo ratings yet

- CHAP2Document8 pagesCHAP2Marlhen Euge SanicoNo ratings yet

- Terminalia Bellerica StudyDocument6 pagesTerminalia Bellerica StudyVaibhav KakdeNo ratings yet

- Piper Betle Linn IkmoDocument3 pagesPiper Betle Linn IkmoHandris SupriadiNo ratings yet

- Effect of 2, 4-d Herbicide on the Stomatal Characteristics of Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.)Document5 pagesEffect of 2, 4-d Herbicide on the Stomatal Characteristics of Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.)Ashique RajputNo ratings yet

- Multiple Medicinal Uses: Moringa Oleifera: A Food Plant WithDocument9 pagesMultiple Medicinal Uses: Moringa Oleifera: A Food Plant WithSilfia LayliyahNo ratings yet

- 718 - 723 PDFDocument6 pages718 - 723 PDFPaola RubioNo ratings yet

- FlaxDocument9 pagesFlaxXeeshan Rafique MirzaNo ratings yet

- Keyterms: Diabetic, Ethanolic Extract, Terminalia Catappa, Winstar Rat, HyperglycemicDocument20 pagesKeyterms: Diabetic, Ethanolic Extract, Terminalia Catappa, Winstar Rat, HyperglycemicJulie Jr GulleNo ratings yet

- Breadfruit: Antioxidant and Health BenefitDocument12 pagesBreadfruit: Antioxidant and Health Benefitfatin ahzaNo ratings yet

- NutmegDocument10 pagesNutmegapi-287730830No ratings yet

- Nutritional Quality and Health Benefits of Okra (AbelmoschusDocument11 pagesNutritional Quality and Health Benefits of Okra (AbelmoschusDarryl Faith RuinaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacological Activities of Baheda (Terminalia: Bellerica) : A ReviewDocument4 pagesPharmacological Activities of Baheda (Terminalia: Bellerica) : A ReviewDavid BriggsNo ratings yet

- Project On GroundnutDocument29 pagesProject On GroundnutjeremiahNo ratings yet

- Bio Term PaperDocument8 pagesBio Term PaperJelord Rey GulleNo ratings yet

- Study report on the medicinal plant Ephedra foliataDocument16 pagesStudy report on the medicinal plant Ephedra foliatavishwanathz47No ratings yet

- Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Medicinal Properties of Carthamus Tinctorius LDocument8 pagesPhytochemistry, Pharmacology and Medicinal Properties of Carthamus Tinctorius LAlexandra GalanNo ratings yet

- Omar M Moma Thesis Outline 2Document20 pagesOmar M Moma Thesis Outline 2Nor-Ton NB BatingkayNo ratings yet

- Ruchels Final Critic Kundol PrunesDocument34 pagesRuchels Final Critic Kundol PrunesJocel BorceloNo ratings yet

- Randia SpinosaDocument5 pagesRandia SpinosaamritaryaaligarghNo ratings yet

- Guava Leaves Preserve BananasDocument13 pagesGuava Leaves Preserve BananasJaica Mangurali TumulakNo ratings yet

- Anti-Hyperlipidemic Effect of Aqueous Leaf Extract of Emilia Praetermissa Milne-Redh (Asteraceae) in RatsDocument10 pagesAnti-Hyperlipidemic Effect of Aqueous Leaf Extract of Emilia Praetermissa Milne-Redh (Asteraceae) in RatsInternational Network For Natural Sciences100% (1)

- Anti-microbial and antioxidant properties of Amlok (Diospyros lotus Linn.) fruit extractsDocument4 pagesAnti-microbial and antioxidant properties of Amlok (Diospyros lotus Linn.) fruit extractstayyaba mehmoodNo ratings yet

- Abubakar and Naomi's Project 2022Document4 pagesAbubakar and Naomi's Project 2022Ahmad OlaiyaNo ratings yet

- Tylophora IndicaDocument18 pagesTylophora IndicaRatan Deep ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Screening of The Antioxidant Properties of The Leaf Extracts of Philippine Medicinal Plants Ficus Nota (Blanco) Merr.Document7 pagesScreening of The Antioxidant Properties of The Leaf Extracts of Philippine Medicinal Plants Ficus Nota (Blanco) Merr.almairahNo ratings yet

- RLDocument16 pagesRLFrancheska Pave CabundocNo ratings yet

- Peteros and UyDocument8 pagesPeteros and UyChérie XuanzaNo ratings yet

- Rio Fatty Acids in BorageDocument8 pagesRio Fatty Acids in BorageAntonio Deharo BailonNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology - 2010 - Maurya - Chemistry and Pharmacology of Withania Coagulans An AyurvedicDocument8 pagesJournal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology - 2010 - Maurya - Chemistry and Pharmacology of Withania Coagulans An AyurvedicfabiNo ratings yet

- Acute Toxicity of Opuntia Ficus Indica and Pistacia Lentiscus Seed Oils in Miceafrican Journal of Traditional Complementary and Alternative MedicinesDocument5 pagesAcute Toxicity of Opuntia Ficus Indica and Pistacia Lentiscus Seed Oils in Miceafrican Journal of Traditional Complementary and Alternative MedicinesRihabNo ratings yet

- ) Seed: Extraction and Characterization of Oil From Daucus Carota (CarrotDocument23 pages) Seed: Extraction and Characterization of Oil From Daucus Carota (CarrotPeter DindahNo ratings yet

- Averrhoa Carambola, L. Leaf Extract: Raju V.K., 2003Document51 pagesAverrhoa Carambola, L. Leaf Extract: Raju V.K., 2003REJILALNo ratings yet

- Kadapa BananaDocument21 pagesKadapa BananaChandrasekhar ReddypemmakaNo ratings yet

- 91858Document52 pages91858Raju KommiriNo ratings yet

- Sacha InchiDocument8 pagesSacha InchiIngeniero Alfonzo Díaz GuzmánNo ratings yet

- Liquorice Root: A Monograph On World Wide Trade ofDocument12 pagesLiquorice Root: A Monograph On World Wide Trade ofVinay MishraNo ratings yet

- Aegyptiaca Del: An Important Ethnomedicinal Plant BalaniteDocument7 pagesAegyptiaca Del: An Important Ethnomedicinal Plant BalanitePharmacy Admission ExpertNo ratings yet

- Curry Leaf Plant: Growing Practices and Nutritional InformationFrom EverandCurry Leaf Plant: Growing Practices and Nutritional InformationNo ratings yet

- Indian Drug LawsDocument4 pagesIndian Drug LawsbilalmasNo ratings yet

- Agents Affecting PigmentationDocument2 pagesAgents Affecting PigmentationYovano TiwowNo ratings yet

- Formulas FarmaceuticasDocument544 pagesFormulas FarmaceuticasUrsula Hille75% (4)

- VHRM 10 523Document18 pagesVHRM 10 523Yovano TiwowNo ratings yet

- Modern Dispensing Pharmacy COVERDocument7 pagesModern Dispensing Pharmacy COVERYovano Tiwow0% (1)

- McDonalds and KFC RecipesDocument2 pagesMcDonalds and KFC RecipesSir Hacks alot100% (1)

- SulfurDocument6 pagesSulfurYovano TiwowNo ratings yet

- Svematiccc PDFDocument1 pageSvematiccc PDFYovano TiwowNo ratings yet

- Native Plant Species of India: Banyan, Peepal, Teak and MoreDocument12 pagesNative Plant Species of India: Banyan, Peepal, Teak and MoreRam Gokhul RNo ratings yet

- Eejay Arms: Coconut Cultivator'S GuideDocument22 pagesEejay Arms: Coconut Cultivator'S Guide1979mi100% (1)

- PAM Principles of Natural Farming Ver 3Document88 pagesPAM Principles of Natural Farming Ver 3Gold FarmNo ratings yet

- How To Use Aloe Vera Gel For Hair GrowthDocument27 pagesHow To Use Aloe Vera Gel For Hair Growthkishan2016No ratings yet

- Living Physical Geography 1st Edition Gervais Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument38 pagesLiving Physical Geography 1st Edition Gervais Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFestelleflowerssgsop100% (13)

- The Coconut Tree restaurant expansion case studyDocument4 pagesThe Coconut Tree restaurant expansion case studyAminath Noor ibrahimNo ratings yet

- Guerrero V CA (GR L-44570)Document5 pagesGuerrero V CA (GR L-44570)Rogie ToriagaNo ratings yet

- 2Q 2010 QresDocument45 pages2Q 2010 QresLiza AmargaNo ratings yet

- Ba132: International Business and Trade (Final Requirements)Document9 pagesBa132: International Business and Trade (Final Requirements)MarjonNo ratings yet

- Andhra Pradesh Horticultural University: Coastal ZoneDocument52 pagesAndhra Pradesh Horticultural University: Coastal ZonessvrNo ratings yet

- Effect of Foliar Liquid Organic Fertilizer On Neera ProductionDocument4 pagesEffect of Foliar Liquid Organic Fertilizer On Neera ProductionMuhammad Maulana SidikNo ratings yet

- Rizal in Dapitan - Being A FarmerDocument2 pagesRizal in Dapitan - Being A FarmerCHERYL TENCHAVEZ DEANONo ratings yet

- Coco Flour Flow ChartDocument3 pagesCoco Flour Flow ChartWilliam PulupaNo ratings yet

- PLANT ResearchDocument6 pagesPLANT ResearchArpita BandekarNo ratings yet

- Mushroom Growers Handbook 1 Mushworld Com Chapter 5 2Document4 pagesMushroom Growers Handbook 1 Mushworld Com Chapter 5 2Jeanelle DenostaNo ratings yet

- How To Make Sandwich INGREDIENTS (Measuring Cup Used, 1 Cup 250 ML)Document2 pagesHow To Make Sandwich INGREDIENTS (Measuring Cup Used, 1 Cup 250 ML)rilaNo ratings yet

- AttachmentDocument4 pagesAttachmentAnna GomezNo ratings yet

- Design Refresher FInalDocument458 pagesDesign Refresher FInalShine BravoNo ratings yet

- Coconut Article Highlights Tree's Many Uses & ChallengesDocument2 pagesCoconut Article Highlights Tree's Many Uses & ChallengesRadia Khandaker ProvaNo ratings yet

- Achm PDFDocument61 pagesAchm PDFAnnNo ratings yet

- Development of Multipurpose Coconut Cutting Machine: International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET)Document6 pagesDevelopment of Multipurpose Coconut Cutting Machine: International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET)Sibakanta SahuNo ratings yet

- Suroy Ta Sa KapalongDocument5 pagesSuroy Ta Sa KapalongLittle MixerNo ratings yet

- CAK Publications 2010Document3 pagesCAK Publications 2010zakuan79No ratings yet

- Factsheet LCF Sustainable Coconut Project Solomon Islands Final PDFDocument2 pagesFactsheet LCF Sustainable Coconut Project Solomon Islands Final PDFKristine M. BarcenillaNo ratings yet

- The Innovation of Coconut Processing To Virgin Coconut Oil (VCO) Using of The Centrifugal MethodDocument6 pagesThe Innovation of Coconut Processing To Virgin Coconut Oil (VCO) Using of The Centrifugal MethodDave MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Exfoliating Soap Bars: InstructablesDocument9 pagesExfoliating Soap Bars: InstructablesIrma SánchezNo ratings yet

- Types of OrchardDocument21 pagesTypes of OrchardJENNEFER ESCALANo ratings yet

- What Is CocolisapDocument7 pagesWhat Is Cocolisapbaymax100% (4)

- Coir PitDocument110 pagesCoir Pittest1100% (2)

- Automated Cocos Nucifera Testa Peeling MachineDocument12 pagesAutomated Cocos Nucifera Testa Peeling Machinelance galorportNo ratings yet