Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Caring For The Cancer Patient

Uploaded by

Agung HaryadiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Caring For The Cancer Patient

Uploaded by

Agung HaryadiCopyright:

Available Formats

Caring for the Cancer Patient

Key points

Net all patients with cancer will require specialist palliative care.

Care can be shared between an oncologist and a palliative medicine physician.

Patients may need intermittent palliative medicine input from diagnosis.

Much can be done by those trained in the principles of general palliative care.

Introduction

The growth of palliative medicine and palliative care services (PCS) has been rapid in the last IC years.

The expansion of these services has led to increased specialization of palliative care. Not all patients

with cancer will require specialist palliative care as their symptoms and problems can be dealt with by

staff. such as oncology ward nurses, who are able to give general supportive care. Hospices and

palliative care units are increasingly used as tertiary centers prioritizing those patients with complex

physical or psychological problems. Oncology patients may need interventions from palliative medicine

at any time during their illness, and in the United Kingdom they may be under the care of both the

oncologist and palliative medicine physician simultaneously.

In the United States, there is an artificial boundary driven by the reimbursement system of Medicare

and Medicare hospice benefit. This results in patients being transferred to the hospice system only when

life-prolonging treatments are ineffective and death is imminent. This is beginning to change with the

National Consen-sus Project Clinical Practice guidelines from the United States stating that 'the effort to

integrate palliative care into all health care for persons with debilitating and life-threatening illnesses

should help to ensure that pain and symptom control, psychological distress, spiritual issues and

practical needs are addressed with patient and family throughout the continuum of care."

Key concepts

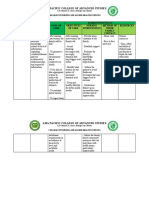

The model shown in Fig. 19.1 illustrates the continuum of pallia-tive care, which should be accessed in

acute hospitals, hospices, or the community, and differentiates between palliative care and what is

called "terminal care" in the United Kingdom and "hospice care" in the United States.

Communication with the cancer patient

Excellent care is difficult to achieve without good communica-tion. By finding out what your patients arc

thinking, and tailor-ing information to what they want to know, communication can be markedly

improved. Current training emphasizes key tasks in communication: Elicit the patient's main problems,

the patient's perceptions of these, and the physical, emotional, and social impact of these problems on

the patient and family; tailor information to what the patient wants to know, checking his or her

understanding; determine how much the patient wants to participate in deci-sion making (when

treatment options are available); discuss treatment options so that the patient understands the

implications;

Diagnosis of serious illness

Life-prolonging therapy

Palliative care

are, place in the course of illness (National Consensus guidelines).

pirnize the chance that the patient will follow agreed deci-sionn'sa-bout treatment and advice about

changes in lifestyle. In order to be able to do all these. Tasks, oncologists need to be r co wnicate

clearly and effectively. 3bile n-Ori,l,nwidely acknowledged that many doctors struggle with effective

communiotion. They feel pressure of time and that if they explore distress during a consultation, they

will be faced with a situation that they cannot handle. mangyConse-any doctors use "blocking

strategies" to prevent further quently, disclosure. Blocking strategies Offering .premature advice or

reassurance" Patient: "I am so worried... (unsaid: "about my 10-c-) Doctor (assuming she knows what

the patient is worried about) "The chemotherapy will work well and you'll be feeling better before you

know it.' Explaining distress as normal Patient: 'I'm so frightened" Doctor 'EverybodyI see feels

frightened at first but that soon goes." Attending to physical aspects only Patient: I'm very worried..."

Doctor 't see. How are your bowels?' Jollying patients along Patient: `Oh I am upset about my cancer.'

Doctor: 'But we should be able to cure it." Switching topic Patient: 'my wife is so upset at the

moment." Doctor `Now have you got your blood test forms for the next cycle of chemo?' Doctors use

strategies like these in the mistaken belief thatthey help, both the patient, by preventing them from

getting upset, and themselves by minimizing the distress that they are exposed to. In fact the opposite is

true: they prevent patients from disclos-ing their anxieties and problems and lead to increased distress

for the patient and the doctor. Exploring these concerns can lead to better joint management of

problems. It can also aid compliance with drugs and treatment programs.

When is palliative care appropriate for cancer patients?

Many oncologists will look after patients until their death. The increasing use of palliative chemotherapy

has prolonged the pal-liative phase in many patients. However, this has also raised new problems,

including when to stop palliative chemotherapy and how to ensure the patient's agreement with the

decision. Palliative care may be required at any time during the patient's treatment. Referral to the

palliative care team (PCT) should also be considered as chemotherapy treatment is discontinued.

Medicare hospice benefit

Caring for the Cancer Patient

Death

Palliative care assessment The assessment of patients needs to be specific, be detailed, and encompass

psychological, social, and existential issues as well as physical problems. Only by paying close attention

to detail will the physician be able to identify the cause of problems and treat them effectively. For

instance, a patient's pain may seem unre-sponsive to opioids not because the morphine is ineffective

but because the patient is fearful of addiction and has not been taking the tablets.

Symptom control

A retrospective case study of 400 patients referred to PCTs showed that 64% had pain, 34% anorexia,

32% constipation, 32% weak-ness, and 31% dyspnea. The most common symptoms are covered in this

chapter. For other problems, the reader may consult the reference list at the end of the chapter.

Pain This may result from the tumor itself, indirectly from tissues related to the cancer, or from other

unrelated causes. In a retro-spective study in 1995, 2074 carers were asked about the patient's

experiences in the last year of life. They reported that 88% of patients were in pain at some time, 47% of

patients' pai.9 was either only partially controlled or not controlled at all by general practioners (GPs),

and 35% had pain partially or not at all con-trolled by hospital doctors. A study of 200 cancer patients

referred to a pain clinic showed that 158 had pain caused by tumor growth; visceral involvement was

the cause in 74 cases, bone secondaries in 68 cases, soft tissue invasion in 56 cases, and nerve

compression or infiltration in 39 cases. Many patients had more than one type of pain. Principles of pain

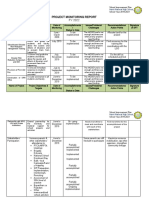

control The analgesic ladder (Fig. 19.2) is a simple scheme which empha-sizes the stepwise approach to

pain due to cancer and the need to take regular analgesics. Step 1 simple nonopioids, for example

paracetamol/ acetaminophen, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSA1Ds) Step 2 opioids for

mild to moderate pain such as co-codamol, codeine, and dihydrocodeine rate to severe pain, for

example Step 3 opioids for mode morphine Move up the ladder if the current step is ineffective. All

Use medication has to be given regularly and orally unless unable to do so.

You might also like

- Congenital Talipes EquinovarusDocument3 pagesCongenital Talipes EquinovarusAgung HaryadiNo ratings yet

- J .'It Nsra"tr Kyytt: LLLSL (UslDocument1 pageJ .'It Nsra"tr Kyytt: LLLSL (UslAgung HaryadiNo ratings yet

- Who Can Provide Effective and Safe Termination of Pregnancy Care? A Systematic ReviewDocument9 pagesWho Can Provide Effective and Safe Termination of Pregnancy Care? A Systematic ReviewAgung HaryadiNo ratings yet

- Validity of Utility Measures For Women With Urge, Stress, and Mixed Urinary IncontinenceDocument6 pagesValidity of Utility Measures For Women With Urge, Stress, and Mixed Urinary IncontinenceAgung HaryadiNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Perspective: New England Journal MedicineDocument3 pagesPerspective: New England Journal MedicinePatrick CommettantNo ratings yet

- Silica Awareness Toolbox TalkDocument2 pagesSilica Awareness Toolbox TalkSamar Husain0% (1)

- Josseicka Reynoso ResumeDocument1 pageJosseicka Reynoso ResumeLouis MarchiNo ratings yet

- Antifungal Catheter Lock Therapy 1Document8 pagesAntifungal Catheter Lock Therapy 1Dakota YamashitaNo ratings yet

- Treating Adult Survivors of Childhood Emotional Abuse and Neglect PDFDocument328 pagesTreating Adult Survivors of Childhood Emotional Abuse and Neglect PDFNegura Giulia100% (19)

- Du ProfessorsDocument28 pagesDu Professorsalka sharmaNo ratings yet

- Sri Mulyani PDFDocument7 pagesSri Mulyani PDFHasna RofifahNo ratings yet

- Training Impulsive Children To Talk To Themselves:: University of WaterlooDocument12 pagesTraining Impulsive Children To Talk To Themselves:: University of WaterlooSalma MedinaNo ratings yet

- His Tory of ODDocument13 pagesHis Tory of ODAmar NathNo ratings yet

- FNCP HyperacidityDocument2 pagesFNCP HyperacidityJeriel DelavinNo ratings yet

- THBHDK 15Document1 pageTHBHDK 15RGNitinDevaNo ratings yet

- Competency-Based Learning Material (Common Competency)Document45 pagesCompetency-Based Learning Material (Common Competency)ZOOMTECHVOC TRAINING&ASSESSMENT100% (1)

- Theories and Principle of Health Care EthicsDocument6 pagesTheories and Principle of Health Care EthicspeachyskizNo ratings yet

- 2022 Annual ReportDocument76 pages2022 Annual ReportLive 5 NewsNo ratings yet

- Church Reoperation Request LetterDocument2 pagesChurch Reoperation Request LetterSir Rannie EspantoNo ratings yet

- COMMENTARYDocument4 pagesCOMMENTARYAdrian CadaNo ratings yet

- First Periodical TestDocument4 pagesFirst Periodical TestSarah mae EmbalsadoNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Ideas DrugsDocument6 pagesDissertation Ideas DrugsBuyPapersOnlineForCollegeUK100% (1)

- Article HealthDocument3 pagesArticle Healthkaii cutieNo ratings yet

- Rubber Band Ligation: of HaemorrhoidsDocument1 pageRubber Band Ligation: of HaemorrhoidsdbedadaNo ratings yet

- The Different Types of InsomniaDocument5 pagesThe Different Types of InsomniaDavid WillNo ratings yet

- Managerial Skill Development Unit-3Document44 pagesManagerial Skill Development Unit-3Arif QuadriNo ratings yet

- CNS Stimulants: College of Pharmacy Department of PharmacologyDocument20 pagesCNS Stimulants: College of Pharmacy Department of PharmacologyDrDeepak PrasharNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Treatment of Spasticity: Cori Ponter, PT, MPT, NCS Barrow Neurological Institute 3/23/19Document76 pagesAssessment and Treatment of Spasticity: Cori Ponter, PT, MPT, NCS Barrow Neurological Institute 3/23/19Praneetha100% (2)

- Count To Ten Allowing YourselfDocument1 pageCount To Ten Allowing YourselfwisgeorgekwokNo ratings yet

- Anila 8611Document18 pagesAnila 8611Anila zafarNo ratings yet

- Rchl1pdf PDF CompressDocument111 pagesRchl1pdf PDF CompressCristian CiocoiuNo ratings yet

- School Based Immunization Form Grade 1Document1 pageSchool Based Immunization Form Grade 1maristellaNo ratings yet

- Professional SummaryDocument3 pagesProfessional SummaryVijay LS SolutionsNo ratings yet

- Project Monitoring Report. GovernanceDocument6 pagesProject Monitoring Report. GovernanceJASMIN FAMANo ratings yet