Professional Documents

Culture Documents

He Philippine Anti

Uploaded by

Nikko Sterling0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views11 pagessdfd

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentsdfd

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views11 pagesHe Philippine Anti

Uploaded by

Nikko Sterlingsdfd

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 11

A.

The Philippine Anti-Plunder Law

Republic Act No. 7080 (July 12, 1991) otherwise known as An Act Defining and Penalizing the Crime of Plunder as

amended defines plunder as the amassing, accumulation or acquisition by any public officer by himself or in connivance

with members of his family, relatives by affinity or consanguinity, business associates, subordinates or other persons of

ill-gotten wealth through a combination of overt or criminal acts in the aggregate or total amount of at least seventy-

five million Philippine pesos. (Section 2, Republic Act No. 7080, as amended)

Ill-gotten wealth means any asset means any asset, property, business enterprise or material possession of any person

acquired by him directly or indirectly through dummies, nominees, agents, subordinates and/or business associates by

any combination or series of the following means or similar schemes:

(a) through misappropriation, conversion, misuse, or malversation of public funds or raids on the public treasury;

(b) by receiving, directly or indirectly, any commission, gift, share, percentage, kickbacks or any other form of

pecuniary benefit from any person and/or entity in connection with any government contract or project or by reason of

the office or position of the public officer concerned;

(c) By the illegal or fraudulent conveyance or disposition of assets belonging to the National Government or any of its

subdivisions, agencies or instrumentalities or government-owned or -controlled corporations and their subsidiaries;

(d) By obtaining, receiving or accepting directly or indirectly any shares of stock, equity or any other form of interest

or participation including promise of future employment in any business enterprise or undertaking;

(e) by establishing agricultural, industrial or commercial monopolies or other combinations and/or implementation of

decrees and orders intended to benefit particular persons or special interests; or

(f) by taking undue advantage of official position, authority, relationship, connection or influence to unjustly enrich

himself or themselves at the expense and to the damage and prejudice of the Filipino people and the Republic of the

Philippines. (Section 1, Republic Act No. 7080, as amended)

Those found guilty of the crime of plunder shall be punished by life imprisonment with perpetual absolute

disqualification from holding any public office. Any person who participated with said public officer in the commission

of plunder shall likewise be punished. In imposing penalties, the court shall consider the guilty parties degree of

participation as well as attendant mitigating and extenuating circumstances. (Section 2, Republic Act No. 7080, as

amended)

The court shall declare any and all ill-gotten wealth and their interests and other incomes and assets including the

properties and shares of stock derived from the deposit or investment thereof forfeited by the State. (Section 2,

Republic Act No. 7080, as amended)

B. Related Jurisprudence

1. Joseph E. Estrada v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 148560, November 19, 2001)

FACTS: On April 4, 2001, the Office of the Ombudsman filed before the Sandiganbayan eight separate Informations

against former President Joseph E. Estrada for violation of the Anti-Plunder Law, as amended, the Anti-Graft and

Corrupt Practices Act, the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees, for perjury under

the Revised Penal Code and for illegal use of an alias under Commonwealth Act No. 142 as amended by Republic Act

No. 6085.

On April 11, 2001, the petitioner filed an Omnibus Motion to remand the case to the Ombudsman for preliminary

investigation, reconsideration and/or reinvestigation of the respective offenses charged and to give the accused the

opportunity to file documents to prove lack of probable cause.

On June 14, 2001, the petitioner moved to quash the Information for the charge of violation of the Anti-Plunder Law on

the grounds that: (a) the facts alleged did not constitute an indictable offense and (b) the said amended Information

charged more than one offense.

ISSUES: (a) Whether the Anti-Plunder Law is unconstitutional for being vague; (b) whether the Anti-Plunder Law

violates the rights of an accused to due process by requiring less evidence to prove the predicate crimes of plunder;

and (c) whether plunder as defined in Republic Act No. 7080 is malum prohibitum and whether it is within the power of

Congress to classify it as such.

HELD: As it is written, the Plunder Law contains ascertainable standards and well-defined parameters which would

enable the accused to determine the nature of his violation. Section 2 is sufficiently explicit in its description of the

acts, conduct and conditions required or forbidden, and prescribes the elements of the crime with reasonable certainty

and particularity.

As long as the law affords some comprehensible guide or rule that would inform those who are subject to it what

conduct would render them liable to its penalties, its validity will be sustained. It must sufficiently guide the judge in

its application; the counsel, in defending one charged with its violation; and more importantly, the accused, in

identifying the realm of the proscribed conduct. Indeed, it can be understood with little difficulty that what the

assailed statute punishes is the act of a public officer in amassing or accumulating ill-gotten wealth of at least

P50,000,000.00 through a series or combination of acts enumerated in Section 1, paragraph (d) of the Anti-Plunder

Law.

Petitioner, however, bewails the failure of the law to provide for the statutory definition of the terms "combination"

and "series" in the key phrase "a combination or series of overt or criminal acts" found in Section 1, paragraph (d), and

Section 2, and the word "pattern" in Section 4.

A statute is not rendered uncertain and void merely because general terms are used therein, or because of the

employment of terms without defining them. Besides, there is no positive constitutional or statutory command

requiring the legislature to define each and every word in an enactment. Congress is not restricted in the form of

expression of its will, and its inability to so define the words employed in a statute will not necessarily result in the

vagueness or ambiguity of the law so long as the legislative will is clear, or at least, can be gathered from the whole

act, which is distinctly expressed in the Plunder Law.

Moreover, it is a well-settled principle of legal hermeneutics that words of a statute will be interpreted in their

natural, plain and ordinary acceptation and signification, unless it is evident that the legislature intended a technical

or special legal meaning to those words The intention of the lawmakers who are, ordinarily, untrained philologists

and lexicographers to use statutory phraseology in such a manner is always presumed. Thus, Webster's New

Collegiate Dictionary contains the following commonly accepted definition of the words "combination" and "series:"

Combination the result or product of combining; the act or process of combining. To combine is to bring into such

close relationship as to obscure individual characters.

Series a number of things or events of the same class coming one after another in spatial and temporal succession.

That Congress intended the words "combination" and "series" to be understood in their popular meanings is pristinely

evident from the legislative deliberations on the bill, which eventually became Republic Act No. 7080 or the Anti-

Plunder Law.

Thus, when the Anti-Plunder Law speaks of "combination," it is referring to at least two acts falling under different

categories of enumeration provided in Section 1, paragraph (d), e.g., raids on the public treasury in Section 1,

paragraph (d), subparagraph (1), and fraudulent conveyance of assets belonging to the National Government under

Section 1, paragraph (d), subparagraph (3).

On the other hand, to constitute a "series" there must be two or more overt or criminal acts falling under the same

category of enumeration found in Section 1, paragraph (d), say, misappropriation, malversation and raids on the public

treasury, all of which fall under Section 1, paragraph (d), subparagraph (1). Verily, had the legislature intended a

technical or distinctive meaning for "combination" and "series," it would have taken greater pains in specifically

providing for it in the law.

As for "pattern," that this term is sufficiently defined in Section 4, in relation to Section 1, paragraph (d), and Section

2. A 'pattern' consists of at least a combination or series of overt or criminal acts enumerated in subsections (1) to (6)

of Section 1 (d). Secondly, pursuant to Section 2 of the law, the pattern of overt or criminal acts is directed towards a

common purpose or goal that is to enable the public officer to amass, accumulate or acquire ill-gotten wealth. And

thirdly, there must either be an 'overall unlawful scheme' or 'conspiracy' to achieve said common goal. As commonly

understood, the term 'overall unlawful scheme' indicates a 'general plan of action or method' which the principal

accused and public officer and others conniving with him, follow to achieve the aforesaid common goal. In the

alternative, if there is no such overall scheme or where the schemes or methods used by multiple accused vary, the

overt or criminal acts must form part of a conspiracy to attain a common goal.

Hence, it cannot plausibly be contended that the law does not give a fair warning and sufficient notice of what it seeks

to penalize. Under the circumstances, petitioner's reliance on the "void-for-vagueness" doctrine is manifestly

misplaced. The doctrine has been formulated in various ways, but is most commonly stated to the effect that a statute

establishing a criminal offense must define the offense with sufficient definiteness that persons of ordinary intelligence

can understand what conduct is prohibited by the statute. It can only be invoked against that specie of legislation that

is utterly vague on its face, i.e., that which cannot be clarified either by a saving clause or by construction.

The second issue that petitioner advances is that Section 4 of the Plunder Law circumvents the immutable obligation of

the prosecution to prove beyond reasonable doubt the predicate acts constituting the crime of plunder when it

requires only proof of a pattern of overt or criminal acts showing unlawful scheme or conspiracy, thus:

SEC. 4. Rule of Evidence. For purposes of establishing the crime of plunder, it shall not be necessary to prove each

and every criminal act done by the accused in furtherance of the scheme or conspiracy to amass, accumulate or

acquire ill-gotten wealth, it being sufficient to establish beyond reasonable doubt a pattern of overt or criminal acts

indicative of the overall unlawful scheme or conspiracy. (Emphasis supplied.)

In a criminal prosecution for plunder, as in all other crimes, the accused always has in his favor the presumption of

innocence which is guaranteed by the Bill of Rights, and unless the State succeeds in demonstrating by proof beyond

reasonable doubt that culpability lies, the accused is entitled to an acquittal.

Thus, in addition to proving the commission of the separate acts constitutive of plunder, the prosecution needs to

prove beyond reasonable doubt a number of acts sufficient to form a combination or series which would constitute a

pattern and involving an amount of at least P50,000,000.00 (now P75,000,000.00 under RA 7080, as amended), viz.:

To illustrate, supposing that the accused is charged in an Information for plunder with having committed fifty (50)

raids on the public treasury. The prosecution need not prove all these fifty (50) raids, it being sufficient to prove by

pattern at least two (2) of the raids beyond reasonable doubt provided only that they amounted to at least

P50,000,000.00 (now P75,000,000.00 under RA 7080, as amended).

Thus, the court explained that Section 4 of the Anti-Plunder Law is intended to be purely a procedural measure and

does not define or establish any substantive right in favor of the accused and thus granting that it is flawed it may

simply be severed without necessarily affecting the validity of the remaining provisions of the Anti-Plunder Law, viz.:

It purports to do no more than prescribe a rule of procedure for the prosecution of a criminal case for plunder. Being

a purely procedural measure, Sec. 4 does not define or establish any substantive right in favor of the accused but only

operates in furtherance of a remedy. It is only a means to an end, an aid to substantive law. Indubitably, even without

invoking Sec. 4, a conviction for plunder may be had, for what is crucial for the prosecution is to present sufficient

evidence to engender that moral certitude exacted by the fundamental law to prove the guilt of the accused beyond

reasonable doubt. Thus, even granting for the sake of argument that Sec. 4 is flawed and vitiated for the reasons

advanced by petitioner, it may simply be severed from the rest of the provisions without necessarily resulting in the

demise of the law; after all, the existing rules on evidence can supplant Sec. 4 more than enough.

As regards the third issue, plunder is malum in se which requires proof of criminal intent. Thus, the ponente in Joseph

E. Estrada v. Sandiganbayan quoted the concurring opinion of Justice Mendoza, viz.:

Precisely because the constitutive crimes are mala in se the element of mens rea must be proven in a prosecution

for plunder. It is noteworthy that the amended information alleges that the crime of plunder was committed "willfully,

unlawfully and criminally." It thus alleges guilty knowledge on the part of petitioner. (Emphasis supplied.)

The application of mitigating and extenuating circumstances in the Revised Penal Code to prosecutions under the Anti-

Plunder Law indicates clearly that mens rea is an element of plunder since the degree of responsibility of the offender

is determined by his criminal intent. Further, any doubt as to whether plunder is mala in se or merely mala in prohibita

may be considered as to have been resolved in the affirmative when Congress included it among the heinous crimes

punishable by reclusion perpetua to death in 1993.

Finally, any doubt as to whether the crime of plunder is a malum in se must be deemed to have been resolved in the

affirmative by the decision of Congress in 1993 to include it among the heinous crimes punishable by reclusion

perpetua to death. Other heinous crimes are punished with death as a straight penalty in R.A. No. 7659. Referring to

these groups of heinous crimes, this Court held in People v. Echegaray.

The evil of a crime may take various forms. There are crimes that are, by their very nature, despicable, either

because life was callously taken or the victim is treated like an animal and utterly dehumanized as to completely

disrupt the normal course of his or her growth as a human being Seen in this light, the capital crimes of kidnapping

and serious illegal detention for ransom resulting in the death of the victim or the victim is raped, tortured, or

subjected to dehumanizing acts; destructive arson resulting in death; and drug offenses involving minors or resulting in

the death of the victim in the case of other crimes; as well as murder, rape, parricide, infanticide, kidnapping and

serious illegal detention, where the victim is detained for more than three days or serious physical injuries were

inflicted on the victim or threats to kill him were made or the victim is a minor, robbery with homicide, rape or

intentional mutilation, destructive arson, and carnapping where the owner, driver or occupant of the carnapped

vehicle is killed or raped, which are penalized by reclusion perpetua to death, are clearly heinous by their very

nature.

There are crimes, however, in, which the abomination lies in the significance and implications of the subject

criminal acts in the scheme of the larger socio-political and economic context in which the state finds itself to be

struggling to develop and provide for its poor and underprivileged masses. Reeling from decades of corrupt tyrannical

rule that bankrupted the government and impoverished the population, the Philippine Government must muster the

political will to dismantle the culture of corruption, dishonesty, greed and syndicated criminality that so deeply

entrenched itself in the structures of society and the psyche of the populace. [With the government] terribly lacking

the money to provide even the most basic services to its people, any form of misappropriation or misapplication of

government funds translates to an actual threat to the very existence of government, and in turn, the very survival of

the people it governs over. Viewed in this context, no less heinous are the effect and repercussions of crimes like

qualified bribery, destructive arson resulting in death, and drug offenses involving government official, employees or

officers, that their perpetrators must not be allowed to cause further destruction and damage to society." (Emphasis

supplied.)

The legislative declaration in R.A. No. 7659 that plunder is a heinous offense implies that it is a malum in se. For

when the acts punished are inherently immoral or inherently wrong, they are mala in se and it does not matter that

such acts are punished in a special law, especially since in the case of plunder the predicate crimes are mainly mala in

se. Indeed, it would be absurd to treat prosecutions for plunder as though they are mere prosecutions for violations of

the Bouncing Check Law (B.P. Blg. 22) or of an ordinance against jaywalking, without regard to the inherent wrongness

of the acts.

Our nation has been racked by scandals of corruption and obscene profligacy of officials in high places which have

shaken its very foundation. The anatomy of graft and corruption has become more elaborate in the corridors of time as

unscrupulous people relentless]y contrive more and more ingenious ways to bilk the coffers of the government. Drastic

and radical measures are imperative to fight the increasingly sophisticated, extraordinarily methodical and

economically catastrophic looting of the national treasury. Such is the Plunder Law, especially designed to disentangle

those ghastly tissues of grand-scale corruption which, if left unchecked, will spread like a malignant tumor and

ultimately consume the moral and institutional fiber of our nation. The Plunder Law, indeed, is a living testament to

the will of the legislature to ultimately eradicate this scourge and thus secure society against the avarice and other

venalities in public office.

Thus, the Court clarified that plunder is inherently wrong and immoral. With the government in dire lack of money to

provide even the most basic services to the people, any form of misappropriation or misapplication of government

funds translates to an actual threat to the very existence of government and the survival of the people and thus is no

less heinous in effect than crimes such as destructive arson resulting in death. The Congress in enacting the Anti-

Plunder Law was simply mustering the political will to dismantle the culture of corruption, dishonesty, greed and

syndicated criminality that has deeply entrenched itself in the structures of society and the psyche of the populace.

2. Jose Jinggoy Estrada v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 148965, February 26, 2002)

FACTS: In November 2000, as an offshoot of the impeachment proceedings against the former President of the

Philippines Joseph Ejercito Estrada, five criminal complaints against the former President and members of his family,

his associates, friends and conspirators were filed with the respondent Office of the Ombudsman.

On April 4, 2001, the Ombudsman issued a Joint Resolution finding probable cause warranting the filing with the

Sandiganbayan of several criminal charges against the former President and the other respondents therein. One of the

charges was for the plunder under Republic Act No. 7080 and among the respondents was the formers presidents son

the petitioner in this case Jose "Jinggoy" Estrada, then mayor of San Juan, Metro Manila.

The charge was amended and filed on April 18, 2001. Docketed as Criminal Case No. 26558, the case was assigned to

the Third Division of the Sandiganbayan. The arraignment of the accused was set on July 10, 2001. No bail for

petitioner's provisional liberty was fixed. On April 24, 2001, petitioner filed a "Motion to Quash or Suspend" the

Amended Information on the ground that the Anti-Plunder Law, Republic Act No. 7080, is unconstitutional and that it

charged more than one offense. Respondent Ombudsman opposed the motion.

On April 25, 2001, the respondent court issued a warrant of arrest for petitioner and his co-accused. On its basis,

petitioner and his co-accused were placed in custody of the law. On April 30, 2001, petitioner filed a "Very Urgent

Omnibus Motion" alleging that: (1) no probable cause exists to put him on trial and hold him liable for plunder, it

appearing that he was only allegedly involved in illegal gambling and not in a "series or combination of overt or

criminal acts" as required in R.A. No. 7080; and (2) he is entitled to bail as a matter of right.

On July 9, 2001, the Sandiganbayan issued a Resolution denying petitioner's "Motion to Quash and Suspend" and "Very

Urgent Omnibus Motion." Petitioner's alternative prayer to post bail was set for hearing after arraignment of all the

accused.

The Amended Information is divided into three parts: (1) the first paragraph charges former President Joseph E.

Estrada with the crime of plunder together with petitioner Jose "Jinggoy" Estrada, Charlie "Atong" Ang, Edward Serapio,

Yolanda Ricaforte and others; (2) the second paragraph spells out in general terms how the accused conspired in

committing the crime of plunder; and (3) the four sub-paragraphs (a) to (d) describe in detail the predicate acts

constitutive of the crime of plunder pursuant to items (1) to (6) of R.A. No. 7080, and state the names of the accused

who committed each act.

Pertinent to the case at bar is the predicate act alleged in subparagraph (a) of the Amended Information which is of

"receiving or collecting, directly or indirectly, on several instances, money in the aggregate amount of P545,000,000.00

for illegal gambling in the form of gift, share, percentage, kickback or any form of pecuniary benefit" In this

subparagraph (a), petitioner, in conspiracy with former President Estrada, is charged with the act of receiving or

collecting money from illegal gambling amounting to P545 million

ISSUES: (a) Whether the Anti-Plunder Law, Republic Act No. 7080, is unconstitutional; (b) whether petitioner Jose

Jinggoy Estrada may be tried for plunder, it appearing that he was only allegedly involved in one act or offense that

is illegal gambling and not in a "series or combination of overt or criminal acts" as required in R.A. No. 7080; and (c)

whether the petitioner is entitled to bail as a matter of right.

RULING: Regarding the first issue, the constitutionality of Republic Act No. 7080 has already been settled in the case of

Joseph Estrada v. Sandiganbayan.

With respect to the second issue, while it is clear that all the accused named in sub-paragraphs (a) to (d) thru their

individual acts conspired with the former President Estrada to enable the latter to amass, accumulate or acquire ill-

gotten wealth in the aggregate amount of P4,097,804,173.17, as the Amended Information is worded, however, it is

not certain whether the accused persons named in sub-paragraphs (a) to (d) conspired with each other to enable the

former President to amass the subject ill-gotten wealth.

In view of the lack of clarity in the Information, the Court held petitioner Jose Jinggoy Estrada cannot be penalized

for the conspiracy entered into by the other accused with the former President as related in the second paragraph of

the Amended Information in relation to its sub-paragraphs (b) to (d). Instead, the petitioner can be held accountable

only for the predicate acts that he allegedly committed as related in sub-paragraph (a) of the Amended Information

which were allegedly done in conspiracy with the former President whose design was to amass ill-gotten wealth

amounting to more than P4 billion.

However, if the allegation should be proven, the penalty of petitioner cannot be unclear. It. will be no different from

that of the former President for in conspiracy, the act of one is the act of the other. The imposable penalty is provided

in Section 2 of Republic Act No. 7080, viz.:

"Section 2. Any public officer who, by himself or in connivance with the members of his family, relatives by affinity or

consanguinity, business associates, subordinates or other persons, amasses, accumulates or acquires ill-gotten wealth

through a combination or series of overt or criminal acts as described in Section 1 (d) hereof in the aggregate amount

or total value of at least Fifty million pesos (P50,000,000.00) (now P75,000,000.00 under RA 7080, as amended) shall

be guilty of the crime of plunder and shall be punished by reclusion perpetua to death. Any person who participated

with the said public officer in the commission of an offense contributing to the crime of plunder shall likewise be

punished for such offense. In the imposition of penalties, the degree of participation and the attendance of mitigating

and extenuating circumstances, as provided by the Revised Penal Code, shall be considered by the court."

The Court added that it cannot fault the Ombudsman for including the predicate offenses alleged in sub-paragraphs (a)

to (d) of the Amended information in one and not four separate Informations. The court explained the history of the

Anti-Plunder Law, thus:

A study of the history of R.A. No. 7080 will show that the law was crafted to avoid the mischief and folly of filing

multiple informations. The Anti-Plunder Law was enacted in the aftermath of the Marcos regime where charges of ill-

gotten wealth were filed against former President Marcos and his alleged cronies. Government prosecutors found no

appropriate law to deal with the multitude and magnitude of the acts allegedly committed' by the former President to

acquire illegal wealth. They also found that under the then existing laws such as the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices

Act, the Revised Penal Code and other special laws, the acts involved different transactions, different time and

different personalities. Every transaction constituted a separate crime and required a separate case and the over-all

conspiracy had to be broken down into several criminal and graft charges. The preparation of multiple Informations

was a legal nightmare but eventually, thirty-nine (39) separate and independent cases were filed against practically

the same accused before the Sandiganbayan. R.A. No. 7080 or the Anti-Plunder Law was enacted precisely to address

this procedural problem. This is pellucid in the Explanatory Note to Senate Bill No. 733, viz.:

"Plunder, a term chosen from other equally apt terminologies like kleptocracy and economic treason, punishes the use

of high office for personal enrichment, committed thru a series of acts done not in the public eye but in stealth and

secrecy over a period of time, that may involve so many persons, here and abroad, and which touch so many states and

territorial units. The acts and/or omissions sought to be penalized do not involve simple cases of malversation of public

funds, bribery, extortion, theft and graft but constitute plunder of an entire nation resulting in material damage to the

national economy. The above-described crime does not yet exist in Philippine statute books. Thus, the need to come

up with a legislation as a safeguard against the possible recurrence of the depravities of the previous regime and as a

deterrent to those with similar inclination to succumb to the corrupting influence of power.

Anent the third issue, on December 21, 2001, the Sandiganbayan submitted its Resolution (dated December 20, 2001)

denying petitioner's motion for bail for "lack of factual basis." Basing its finding on the earlier testimony of Dr.

Anastacio, the Sandiganbayan found that petitioner "failed to submit sufficient evidence to convince the court that the

medical condition of the accused requires that he be confined at home and for that purpose that he be allowed to post

bail."

The Court clarified that the crime of plunder is punished with the penalty of reclusion perpetua to death. Under the

Revised Rules of Court, offenses punishable by death, reclusion perpetua or life imprisonment are non-bailable when

the evidence of guilt is strong, to wit:

"Sec. 7. Capital offense or an offense punishable by reclusion perpetua or life imprisonment, not bailable. No person

charged with a capital offense, or an offense punishable by reclusion perpetua or life imprisonment, shall be admitted

to bail when evidence of guilt is strong, regardless of the stage of the criminal prosecution."

Section 7, Rule 114 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure is based on Section 13, Article III of the 1987

Constitution which reads:

"Sec. 13. All persons, except those charged with offenses punishable by reclusion perpetua when evidence of guilt is

strong, shall, before conviction be bailable by sufficient sureties, or be released on recognizance as may be provided

by law. The right to bail shall not be impaired even when the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus is suspended.

Excessive bail shall not be required."

Thus, the constitutional mandate makes the grant or denial of bail in capital offenses hinge on the issue of whether or

not the evidence of guilt of the accused is strong. The trial court is required to conduct bail hearings wherein both the

prosecution and the defense will be afforded sufficient opportunity to present their respective evidence. The burden of

proof lies with the prosecution to show that the evidence of guilt is strong.

The hearings on which respondent court based its Resolution of December 20, 2001 involved the reception of medical

evidence only and which evidence was given five months earlier in September 2001. The records do not show that

evidence on petitioner's guilt was presented before the lower court. Thus, the Sandiganbayan was ordered to conduct

hearings to ascertain whether evidence of petitioner's guilt is strong to determine whether to grant bail to the latter.

3. Serapio v. Sandiganbayan (G.R. No. 148468, January 28, 2003)

FACTS: The case of Serapio v. Sandiganbayan is an offshoot of the case filed against former president Joseph E. Estrada

as the petitioner is one of the accused charged with plunder together with the former president and Jose Jinggoy

Estrada. It is a consolidation of three cases filed by petitioner with the Supreme Court against the Sandiganbayan and

other respondents.

ISSUE: As mentioned in the earlier cited case of Jose Jinggoy Estrada v. Sandiganbayan, according to the accused

Estradas and Edward Serapio the information charges more than one offense, namely, bribery (Article 210 of the

Revised Penal Code), malversation of public funds or property (Article 217, Revised Penal Code) and violations of Sec.

3(e) of Republic Act (Republic Act No. 3019) and Section 7(d) of Republic Act No. 6713.

RULING: As likewise earlier mentioned, the court found the contention to be unmeritorious. The acts alleged in the

information are not charged as separate offenses but as predicate acts of the crime of plunder. Thus:

It should be stressed that the Anti-Plunder law specifically Section 1(d) thereof does not make any express reference

to any specific provision of laws, other than R.A. No. 7080, as amended, which coincidentally may penalize as a

separate crime any of the overt or criminal acts enumerated therein. The said acts which form part of the combination

or series of act are described in their generic sense. Thus, aside from 'malversation' of public funds, the law also uses

the generic terms 'misappropriation', 'conversion' or 'misuse' of said fund. The fact that the acts involved may likewise

be penalized under other laws is incidental. The said acts are mentioned only as predicate acts of the crime of plunder

and the allegations relative thereto are not to be taken or to be understood as allegations charging separate criminal

offenses punished under the Revised Penal Code, the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act and Code of Conduct and

Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees."

It is clear on the face of the amended Information that petitioner and his co-accused are charged only with one

crime of plunder and not with the predicate acts or crimes of plunder. It bears stressing that the predicate acts merely

constitute acts of plunder and are not crimes separate and independent of the crime of plunder

Further, petitioner argues that his motion for reinvestigation is premised on the absolute lack of evidence to support a

finding of probable cause for plunder as against him. Hence, he should be spared from the inconvenience, burden and

expense of a public trial.

The Court explained that the settled rule that the Court will not interfere with the Ombudsman's discretion in the

conduct of preliminary investigations. Thus, in Raro v. Sandiganbayan (cf. Serapio v. Sandiganbayan), the Court ruled:

" In the performance of his task to determine probable cause, the Ombudsman's discretion is paramount. Thus, in

Camanag vs. Guerrero, this Court said:

[S]uffice it to state that this Court has adopted a policy of non-interference in the conduct of preliminary

investigations, and leaves to the investigating prosecutor sufficient latitude of discretion in the exercise of

determination of what constitutes sufficient evidence as will establish 'probable cause' for filing of information against

the supposed offender."

Petitioner has the burden of establishing that the Sandiganbayan committed grave abuse of discretion in issuing its

resolution affirming the finding of probable cause against him by the Ombudsman. Petitioner failed to discharge his

burden and thus the Court found no grave abuse of discretion on the part of the Sandiganbayan.

The Court elucidated that preliminary investigation is conducted only for the purpose of determining whether a crime

has been committed and whether there is probable cause to believe that the person accused of the crime is guilty

thereof and should be held for trial. As the Court held in Webb v. De Leon (cf. Serapio v. Sandiganbayan):

"A finding of probable cause needs only to rest on evidence showing that more likely than not a crime has been

committed and was committed by the suspect. Probable cause need not be based on clear and convincing evidence of

guilt, neither on evidence establishing guilt beyond reasonable doubt and definitely, not on evidence establishing

absolute certainty of guilt.''

OTHER ISSUES: In one of the petitions the issues for resolution were: (a) Whether or not the petitioner should first be

arraigned before hearings of his petition for bail may be conducted; (b) whether the petitioner may file a motion to

quash the amended Information during the pendency of his petition for bail; (c) whether a joint hearing of the petition

for bail of petitioner and those of the other accused is mandatory; (d) whether the People waived their right to adduce

evidence in opposition to the petition for bail of petitioner and failed to adduce strong evidence of guilt of petitioner

for the crime charged; and (e) whether the petitioner was deprived of his right to due process and should thus be

released from detention via a writ of habeas corpus.

RULING: Regarding the issue in (a) above, the arraignment of an accused is not a prerequisite to the conduct of

hearings on his petition for bail. A person is allowed to petition for bail as soon as he is deprived of his liberty by virtue

of his arrest or voluntary surrender. An accused need not wait for his arraignment before filing a petition for bail.

In Lavides vs. Court of Appeals (cf. Serapio v. Sandiganbayan) the Court held that "in cases where it is authorized, bail

should be granted before arraignment, otherwise the accused may be precluded from filing a motion to quash."

However, the foregoing pronouncement by the Court should not be taken to mean that the hearing on a petition for

bail should at all times precede arraignment. The ruling in Lavides v. Court of Appealsshould be understood in light of

the fact that the accused in said case filed a petition for bail as well as a motion to quash the informations filed

against him. The Court elucidated thus:

[T]o condition the grant of bail to an accused on his arraignment would be to place him in a position where he has to

choose between (1) filing a motion to quash and thus delay his release on bail because until his motion to quash can be

resolved, his arraignment cannot be held, and (2) foregoing the filing of a motion to quash so that he can be arraigned

at once and thereafter be released on bail. This would undermine his constitutional right not to be put on trial except

upon a valid complaint or Information sufficient to charge him with a crime and his right to bail.

In fine, the Court found the Sandiganbayan to have committed grave abuse of discretion amounting to excess of

jurisdiction in ordering the petitioners arraignment before proceeding with the hearing of his petition for bail.

With regard to the issue in (b) above, filing a motion to quash is the mode by which an accused assails the validity of a

criminal complaint or Information filed against him for insufficiency on its face in point of law, or for defects which are

apparent in the face of the Information. Generally, an accused may file a motion to quash the Information against him

before arraignment.

A motion to quash and a petition for bail do not preclude each other. Certainly, if a petition for bail is granted to an

accused charged with an offense punishable by death, reclusion perpetua or life imprisonment on the ground that the

evidence of his guilt is not strong, the accused may still file a motion to quash to question the validity of the

Information charging him with an offense. However, if a motion to quash a criminal complaint is granted on the ground

that the same does not charge an offense the petition for bail will become moot and academic.

Concerning the issue in (c) above, the Court noted that there is no provision in the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure

or the Rules of Procedure of the Sandiganbayan governing the hearings of two or more petitions for bail filed by

different accused or requiring that a petition for bail of an accused be heard simultaneously with the trial of the case

against the other accused. Thus, the matter is addressed to the sound discretion of the trial court. The Court will not

interfere with the exercise of discretion by the Sandiganbayan except in case proof of grave abuse of discretion

amounting to excess or lack of jurisdiction of the latter can be shown.

The Court pointed out that in Ocampo vs. Bernabe (cf. Serapio v. Sandiganbayan) it held that the court is to conduct

only a summary hearing in a petition for bail hearing. Summary means a brief and speedy method of receiving and

considering the evidence of guilt as is practicable and consistent with the purpose of the hearing which is merely to

determine the weight of evidence for purposes of bail. Thus, in a petition for bail hearing:

The court does not try the merits or enter into any inquiry as to the weight that ought to be given to the evidence

against the accused, nor will it speculate on the outcome of the trial or on what further evidence may be offered

therein. It may confine itself to receiving such evidence as has reference to substantial matters, avoiding unnecessary

thoroughness in the examination and cross-examination of witnesses, and reducing to a reasonable minimum the

amount of corroboration particularly on details that are not essential to the purpose of the hearing.

A joint hearing of separate petitions for bail by several accused may be a way to avoid duplication of time and effort of

the courts and the prosecution and minimize prejudice to accused persons, especially in cases where the petitioners

for bail are charged of having conspired in the commission of the same crime and the prosecution will present

essentially the same evidence against them.

However, the Court explained that due to the complexity of the case involving former president Estrada to which the

Sandiganbayan sought to join the petitioners petition for bail, the bail proceedings will no longer be summary. As

regards former president Estrada, the proceedings will involve a full-blown trial.

Further, in accordance the Courts ruling in the case of Jose Jinggoy Estrada v. Sandiganbayan where it stated that

Jose "Jinggoy" Estrada can only be charged with conspiracy to commit the acts alleged in sub-paragraph (a) of the

amended Information since it is not clear the accused persons conspired with each other to assist Joseph Estrada to

amass ill-gotten wealth in committing all the acts alleged in in sub-paragraphs (a) to (d) thereof, the Court held that

Serapio may only be charged with having conspired with the other co-accused named in sub-paragraph (a) by "receiving

or collecting, directly or indirectly, on several instances, money from illegal gambling, in consideration of

toleration or protection of illegal gambling.

Thus, the Court found the Sandiganbayan to have gravely abused its discretion in ordering that the petition for bail of

petitioner and the trial of former President Joseph E. Estrada be held jointly. Thus:

In ordering that petitioner's petition for bail to be heard jointly with the trial of the case against his co-accused

former President Joseph E. Estrada, the Sandiganbayan in effect allowed further and unnecessary delay in the

resolution thereof to the prejudice of petitioner. In fine then, the Sandiganbayan committed a grave abuse of its

discretion in ordering a simultaneous hearing of petitioner's petition for bail with the trial of the case against former

President Joseph E. Estrada on its merits.

Cooley in his treatise Constitutional Limitations (cf. Serapio v. Sandiganbayan) explained the rationale for the speedy

resolution of an application for bail, thus:

"For, if there were any mode short of confinement which would with reasonable certainty insure the attendance of the

accused to answer the accusation, it would not be justifiable to inflict upon him that indignity, when the effect is to

subject him in a greater or lesser degree, to the punishment of a guilty person, while as yet it is not determined that

he has not committed any crime."

With respect to the issue in (d) above on whether the People waived their right to adduce evidence in opposition to the

petition for bail of petitioner and failed to adduce strong evidence of guilt of petitioner for the crime charged, the

Court found the petitioners claim to be unsupported by the cases records. The Sandiganbayan had already scheduled

the hearing dates for the petitioners application for bail but the same had to be reset due to incidents raised in

several other motions filed by the parties.

Thus, the Court ruled that the petitioner cannot be released from detention until the Sandiganbayan has conducted a

hearing of his application for bail and resolved the same in his favor. Prior thereto, there must first be a finding that

the evidence against petitioner is not strong before he may be granted bail.

Anent the last issue raised in (e) above as to whether the petitioner was deprived of his right to due process and should

thus be released from detention via a writ of habeas corpus, the Court found no basis for the issuance of a writ of

habeas corpus in favor of the petitioner.

The Court explained that, as a general rule, the writ of habeas corpus will not issue where the person alleged to be

restrained of his liberty in custody of an officer under a process issued by the court which jurisdiction to do so.

However, in exceptional circumstances, the courts may grant a writ of habeas corpus even when the person concerned

is detained pursuant to a valid arrest or his voluntary surrender.

The writ of liberty is recognized as "the fundamental instrument for safeguarding individual freedom against arbitrary

and lawless state action" due to "its ability to cut through barriers of form and procedural mazes." Thus, in previous

cases, the Court issued the writ where the deprivation of liberty, while initially valid under the law, had later become

invalid, and even though the persons praying for its issuance were not completely deprived of their liberty.

The general rule that habeas corpus does not lie where the person alleged to be restrained of his liberty is in the

custody of an officer under process issued by a court which had jurisdiction to issue the same applies to the petitioner

because he is under detention pursuant to the order of arrest issued by the Sandiganbayan on April 25, 2001 after the

filing by the Ombudsman of the amended information for plunder against petitioner and his co-accused. In fact, the

petitioner voluntarily surrendered himself to the authorities on April 25, 2001 upon learning that a warrant for his

arrest had been issued.

Moreover, the court stated that a petition for habeas corpus is not the appropriate remedy for asserting one's right to

bail. It cannot be availed of where accused is entitled to bail not as a matter of right but on the discretion of the court

and the latter has not abused such discretion in refusing to grant bail, or has not even exercised said discretion. The

proper recourse is to file an application for bail with the court where the criminal case is pending and to allow hearings

thereon to proceed.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- DEED of Abs Sale UcangDocument2 pagesDEED of Abs Sale UcangNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Additional Tax Cases IIDocument21 pagesAdditional Tax Cases IINikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- DEED of Abs Sale UcangDocument2 pagesDEED of Abs Sale UcangNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Ack Bir Ampara de Leon GozonDocument2 pagesAck Bir Ampara de Leon GozonNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Special Proceedings: 1. Explain The Difference Between Action and Special ProceedingDocument2 pagesSpecial Proceedings: 1. Explain The Difference Between Action and Special ProceedingNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- DebateDocument14 pagesDebateNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- BP 22 HandluDocument8 pagesBP 22 HandluNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- PALE - FinalsDocument13 pagesPALE - FinalsNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Income PDFDocument99 pagesIncome PDFNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- China Banking Corp V CADocument7 pagesChina Banking Corp V CANikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Arsenio T. Cornites, CESO VDocument1 pageArsenio T. Cornites, CESO VNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- 3 RR 6-2001 PDFDocument17 pages3 RR 6-2001 PDFJoyceNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- White Gold Marine Services VDocument4 pagesWhite Gold Marine Services VNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- To Balance Its National Drug Control Program: RegulationDocument8 pagesTo Balance Its National Drug Control Program: RegulationNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Bona Fide Relationship Refers To 1 A Physician and Patient Relationship Wherein A Licensed Physician Has Made A Complete Assessment of The PatientDocument4 pagesBona Fide Relationship Refers To 1 A Physician and Patient Relationship Wherein A Licensed Physician Has Made A Complete Assessment of The PatientNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Republic Act No. 4712Document1 pageRepublic Act No. 4712Nikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- The Convention On The Rights of The ChildDocument16 pagesThe Convention On The Rights of The ChildNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- 2005 Conflict CasesDocument7 pages2005 Conflict CasesNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Republic Act No. 4712Document1 pageRepublic Act No. 4712Nikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Batas Pambansa BLG 22Document3 pagesBatas Pambansa BLG 22Nikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Tax Digest 1Document2 pagesTax Digest 1Nikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- We Are Not Against Any OFW Whom We Believe and See As ModernDocument5 pagesWe Are Not Against Any OFW Whom We Believe and See As ModernNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Marubeni V CIR DigestDocument5 pagesMarubeni V CIR DigestNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Marine Insurance CasesDocument5 pagesMarine Insurance CasesNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Mendoza v. Municipality, 94 Phil. 1047 (1954) ), A Tax Levied For A Private PurposeDocument1 pageMendoza v. Municipality, 94 Phil. 1047 (1954) ), A Tax Levied For A Private PurposeNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- RR 16-2008Document8 pagesRR 16-2008Peggy SalazarNo ratings yet

- TaxDocument35 pagesTaxNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Tax Digest 1Document2 pagesTax Digest 1Nikko Sterling100% (2)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Conflict DigestDocument31 pagesConflict DigestNikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Character 66Document1 pageCharacter 66Nikko SterlingNo ratings yet

- Zulm Hindi MovieDocument21 pagesZulm Hindi MovieJagadish PrasadNo ratings yet

- Index From Military Manpower, Armies and Warfare in South AsiaDocument22 pagesIndex From Military Manpower, Armies and Warfare in South AsiaPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- SSS R3 Contribution Collection List in Excel FormatDocument2 pagesSSS R3 Contribution Collection List in Excel FormatJohn Cando57% (14)

- Right To Life and Personal Liberty: - Includes Important CasesDocument51 pagesRight To Life and Personal Liberty: - Includes Important Caseschoudhary7132No ratings yet

- South Korea Defense White Paper 2012Document418 pagesSouth Korea Defense White Paper 2012ericngwNo ratings yet

- Salazar vs. Philippines - GuiltyDocument6 pagesSalazar vs. Philippines - Guiltyalwayskeepthefaith8No ratings yet

- Pagsasalin Sa Kontekstong Filipino (GEED 10113) : Pinal Na Kahingian Sa Ikalawang Semestre NG Taong Panuruan 2020 - 2021Document4 pagesPagsasalin Sa Kontekstong Filipino (GEED 10113) : Pinal Na Kahingian Sa Ikalawang Semestre NG Taong Panuruan 2020 - 2021Hans ManaliliNo ratings yet

- Today's Fallen Heroes Wednesday 6 November 1918 (1523)Document31 pagesToday's Fallen Heroes Wednesday 6 November 1918 (1523)MickTierneyNo ratings yet

- B.A. Prog. Political ScienceDocument44 pagesB.A. Prog. Political ScienceKishoreNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Child Abuse - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFDocument26 pagesChild Abuse - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFBrar BrarNo ratings yet

- Mco BookDocument985 pagesMco BookMuurish DawnNo ratings yet

- Truth Matters Bin LadenDocument1 pageTruth Matters Bin LadenDean HartwellNo ratings yet

- Social Reform Movements of IndiaDocument5 pagesSocial Reform Movements of IndiaMURALIHARAN KNo ratings yet

- 3 - Manuscript Sut Raati 2015Document9 pages3 - Manuscript Sut Raati 2015Ramon MuscatNo ratings yet

- Genesis 39 - Joseph and Potiphar's WifeDocument16 pagesGenesis 39 - Joseph and Potiphar's WifeMarc GajetonNo ratings yet

- Caterisirea Lui Ciprian de Oropos - 1986 PDFDocument11 pagesCaterisirea Lui Ciprian de Oropos - 1986 PDFVio VioletNo ratings yet

- The Three Essentials Preparing For The Perfect DateDocument4 pagesThe Three Essentials Preparing For The Perfect DateJames ZacharyNo ratings yet

- Ylith B. Fausto, Jonathan Fausto, Rico Alvia, Arsenia Tocloy, Lourdes Adolfo and Anecita Mancita, Petitioners, vs. Multi Agri-ForestDocument1 pageYlith B. Fausto, Jonathan Fausto, Rico Alvia, Arsenia Tocloy, Lourdes Adolfo and Anecita Mancita, Petitioners, vs. Multi Agri-ForestAbby EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- 2020 KUSA Product Catalog - FinalDocument7 pages2020 KUSA Product Catalog - FinalTapes AndreiNo ratings yet

- Case Digests Ipl 2Document3 pagesCase Digests Ipl 2Hazel Joy Galamay - GarduqueNo ratings yet

- Apresentation Conseg Diplomatico Abril 2015Document17 pagesApresentation Conseg Diplomatico Abril 2015Mazen Al-RefaeiNo ratings yet

- 4.2 DSC DISTRESS COMMUNICATION Reading Comprehension Book 4.2Document2 pages4.2 DSC DISTRESS COMMUNICATION Reading Comprehension Book 4.2AdiNo ratings yet

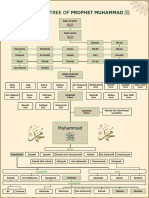

- Family Tree of Prophet MuhammadDocument1 pageFamily Tree of Prophet Muhammadgoogle pro100% (6)

- Wanted Person of The Week-GanglDocument1 pageWanted Person of The Week-GanglHibbing Police DepartmentNo ratings yet

- 11 Lingan Vs Cal UbaquibDocument13 pages11 Lingan Vs Cal UbaquibmilotNo ratings yet

- Announcement of No Information - Brad King - 42-2020-Cf-000516-CFAxxx Felony Drug CaseDocument3 pagesAnnouncement of No Information - Brad King - 42-2020-Cf-000516-CFAxxx Felony Drug CaseNeil GillespieNo ratings yet

- Lay Judge JanuaryDocument331 pagesLay Judge Januaryjmanu9997No ratings yet

- Subject: Guidelines-Review of Size of Zone of ConsiderationDocument8 pagesSubject: Guidelines-Review of Size of Zone of ConsiderationDevulapally SatyanarayanaNo ratings yet

- Paul Writing NotesDocument18 pagesPaul Writing NotesPaulIsaac 0518No ratings yet

- E Commerce Laws in IndiaDocument19 pagesE Commerce Laws in IndiaPriya ZutshiNo ratings yet

- Selling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansFrom EverandSelling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Broken: The most shocking childhood story ever told. An inspirational author who survived it.From EverandBroken: The most shocking childhood story ever told. An inspirational author who survived it.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (45)

- The Bigamist: The True Story of a Husband's Ultimate BetrayalFrom EverandThe Bigamist: The True Story of a Husband's Ultimate BetrayalRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (104)

- Hell Put to Shame: The 1921 Murder Farm Massacre and the Horror of America's Second SlaveryFrom EverandHell Put to Shame: The 1921 Murder Farm Massacre and the Horror of America's Second SlaveryRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (3)

- If You Tell: A True Story of Murder, Family Secrets, and the Unbreakable Bond of SisterhoodFrom EverandIf You Tell: A True Story of Murder, Family Secrets, and the Unbreakable Bond of SisterhoodRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1800)

- Tinseltown: Murder, Morphine, and Madness at the Dawn of HollywoodFrom EverandTinseltown: Murder, Morphine, and Madness at the Dawn of HollywoodNo ratings yet