Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rakhine Rohingya Conflict Analysis

Uploaded by

Nyein ChanyamyayOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rakhine Rohingya Conflict Analysis

Uploaded by

Nyein ChanyamyayCopyright:

Available Formats

Conflict Mapping: Rakhine-Rohingya

Conflict in Myanmar

LB 5525: Conflict Analysis

Min Zaw

Student ID: 12725517

Subject: Conflict Analysis

Subject code: LB5525

Subject Coordinator: Judith Herrmann

Word count: 3617 (excluding cover page, Table of content, References & Annex)

1

Table of Contents

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2

Conflict Parties ...................................................................................................................................... 2

The parties ................................................................................................................................. 2

Relationship among various types of parties.. 3

Power and resources.. 3

Conflict History ...5

Continuum of relationship ......................................................................................................... 5

Past relationship between two parties .6

Conflict Context .7

Level of conflict 7

Multiple levels ..7

Cultural aspects ..8

Behavioral determinants .9

Party orientation .10

Determining issues and objectives .10

Conflict dynamics .12

Behavioral styles .12

Conflict events .12

Action-Reaction process 13

Conflict intervention 15

Conclusion.16

References 17

Annex

Annex 1 ..20

Annex 2 ..21

2

Introduction

Violence occurred in the western part of Myanmar in 2012 between Rakhine and Rohingya

(Annex 1). It resulted in 192 dead and 265 injured, 8614 houses demolished, 32 mosques

and 22 monasteries burned (Inquiry Commission, 2013) with displacement of 100,000

people (Human Rights Watch, 2013). The president of Myanmar appointed an investigation

commission in August, 2012.

This paper will analyze Rakhine-Rohingya conflict using the Shay Bright conflict mapping

chart. This paper will present a balanced view based upon Government and Non-

government (NGO) sources.

Conflict parties

The parties include those who directly or indirectly involve (Bright, n.d.)

Primary parties are those who directly participate and whose goals are incompatible

(Bright, n.d.).

Primary parties in the violence are Rakhine and Rohingya. Rakhine make up 63% of total

population (Inquiry Commission, 2013) in the western costal state of Myanmar. Rakhine are

Buddhists who primarily dwell in central and southern parts of Rakhine state. Rohingya

predominantly reside in north-western Rakhine state and are Muslims (Annex 2).

Rakhine do not accept Rohingya as being ethnic and assert they are economic immigrants

from Bangladesh so they insist upon using the term Bangali rather than Rohingya (Inquiry

Commission, 2013). By contrast, Rohngya regard themselves as an ethnic group of

Myanmar and want their citizenship reinstated which they lost in the 1982 citizenship law

(Inquiry Commission, 2013).

Secondary parties are those who have indirect involvement in the violence (Bright, n.d.)

Buddhist monks and Rakhine political parties initially supported and later organized the

Rakhine population to fight the Rohingya. Simultaneously Rohingya organizations sponsored

the Rohingya. According to Inquiry Commission (2013), these organizations in Yangon, New

York and Landon were calling Rohingya communities in Rakhine state on mobile phones

and urging them to declare themselves Rohingya. Following the initial waves of violence,

local Buddhist monks association and political parties organized Rakhine citizens to drive

Rohingya from the state (Fortify Rights, 2014).

3

Intervening parties are those would have considerable effect on a conflict if they involve

(Bright, n.d.).

Myanmar security forces intervened, however they did not control the violence at the outset,

instead they indirectly supported the Rakhine. Human Rights Watch reported that security

forces did not intervene despite them witnessing the attack of a Rakhine mob in the initial

violence (Human Rights Watch, 2012, p. 20).

Other interested parties are those who have strong interest in the conflict and opinion how

to resolve (Wilmot & Hocker, 177 as cited in Bright, n.d.).

Other interested parties include NGOs, United Nations (UNs) Organizations, international

and local media. Initially Rakhine believed that these organizations would help to address

the challenges equitably but later they perceived that these organizations validated the aid

maldistribution in favor of the Rohingya (Inquiry Commission, 2013). State-controlled and

domestic media outlets claimed that Rohingya instigated the violence whereas international

media focused upon violence committed against Rohingya (Human Rights Watch, 2012).

Relationship among various types of parties (Figure 1)

Buddhist monks association and political parties support Rakhines immaterially. Similarly,

armed forces indirectly aided Rakhine by avoiding lawful actions and repressing Rohingya.

On the other, Rohingya Organizations internationally advocated for Rohingya. Domestic

media agencies focused on violence against Rakhines whereas International media

emphasized violence against Rohingya. Finally the majority of aid from non-governmental

organizations went to Rohingya despite providing humanitarian assistance to both sides and

claiming impartiality.

Power and resources

In a conflict both parties exercise power to win, how much power each is able to muster and

effectively use determines the victor. There are four types of power currencies (Bright, n.d.).

Resource control: The population of Rakhine and Rohingya are 2.2 million and 1.3 million

respectively (Fortify Rights, 2013). Rakhine state is rich in aquatic resources and agriculture

land. Rakhine people hold the rights to cultivate the land, fish and freely trade products while

Rohingya cannot. Furthermore almost all the members of local administrative authorities are

Rakhine.

4

Interpersonal linkage: Rakhine receive support and sympathy from the Buddhist majority of

Myanmar, local media agencies and armed forces whereas Rohingya people receive aid

from NGOs, moral legitimacy from international news media and tactical advice from

Rohingya organizations.

Communication skills: Myanmar language is the main and official dialect but majority of

Rohingya speak Bangalis dialect. Rakhine use both Myanmar and their ethnic languages.

State and domestic media as well as social networks advocate Rakhine position. Meanwhile,

Rohingya receives international media patronage which translates into third party

intermediaries including foreign countries and United Nations validating their position.

Expertise: Skills and education in Rakhine state are generally low especially in rural areas

resulting in only basic labor-intensive industries (Inquiry Commission, 2013). For Rohingya it

is further compounded by the absence of citizenship and lack of access to education.

5

Conflict History

Continuum of relationships

Prior to British colonization, Rohingya and Rakhine lived peacefully together. Rakhine were

the ruling class who owned land and controlled the regions economy whilst Rohingya were

domestic workers serving the Rakhine and their businesses (Inquiry Commission, 2013).

During British rule significant migration of Muslims from Bangladesh to Rakhine occurred

which resulted in ethnic, religious, and socio-economic problems that fostered resentment

from Rakhine community (International Crisis Group, 2013). The resentment erupted into

violence during the Second World War as the Rakhine supported Japanese and Rohingya

remained loyal to British (Internal Crisis Group, 2013).

After the Second World War, the relationship between the two parties further deteriorated

owing to Rohingya mujahidin forces attacking Rakhine Buddhist interests (International

Crisis Group, 2013). Following the 1962 military coup, the military regime employed a

hardline stance on minorities including the Rohingya and a nationwide operation to end

illegal immigration caused 200,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh. (International Crisis

Group, 2013).

During the nationwide surge of unrest in 1988, about 50,000 Rohingya tried to take over

towns in north-western Rakhine state but security personnel resisted the attempt (Inquiry

Commission, 2013). In 1994 a riot occurred due to a dispute between a Buddhist monk and

Rhingya medicine shop owner (Inquiry Commission, 2013). In 1998 a 5000-strong Rohingya

force headed by the Rohngya Liberation Organization destroyed Buddhist monasteries and

killed several Rakhine (Inquiry Commission, 2013). In 2001, riots between Rakhine and

Rohingya transpired in the state capital following an argument between a group of young

monks and a Rohingya stall-owner, which escalated into violence during which twenty

people died, many homes and business torched (International Crisis Group, 2013).

The past history shows tension, conflict and episodes of violence based upon political,

religious and socio-economic factors (Figure 2).

6

Past relationship between two parties

The tension between the two societies began during British colonial rule resulting in frequent

violent encounters. Strong nationalistic attitudes, different social class, and resentment are

the driver of conflict. Armed forces played an important role in de-escalation of past conflicts.

Whenever the country encounters critical situations significant communal crises coincide.

These incidents have built up mistrust and animosity between two parties. Inquiry

Commission (2013) noted that the hatred between parties would not dissipate easily

because such sentiments are rooted in a bitter history.

7

Conflict context

Conflicts do not occur in vacuums: they have personal, interpersonal, social, industrial,

commercial, legal, political, and doubtless many other contexts (Tillett & French, 2006, p.88).

Level of conflict

The most recent conflict in 2012 started at an interpersonal level with a criminal homicidal

rape case committed by three Rohingya which flamed barbaric stereotypes of Rohingya

amongst Rakhine. Afterwards a Rakhine mob killed ten Muslims travelers in a reprisal

attack, this ignited violence between the two parties. Later, Buddhist monks and Rakhine

political parties mobilized and were deeply engaged in the conflict. In 2013 the 969-

movement led by extremist Buddhists nationalists enabled the conflict to move beyond

Rakhine state into cities across the country where anti-Muslims violence ensued. The

negative stereotyping boosted polarization and collective identities of both groups, thus

elevating the conflict to societal level.

According to Hill (2013), there is significant displacement and asylum flow into neighboring

countries including; Bangladesh, Thailand, and Malaysia. This outflow of refugees spread

awareness of the situation in Myanmar, stirred up local Muslim populations in countries

where they landed and resulted in a wave of international media reporting their stories. By

2013, United Nations General Assemblys human rights committee urged Myanmar

government to grant Rohingya citizenship rights (Kyaw Hsu Mon, 2013). The organization of

Islamic countries (OIC) called for opening its offices for humanitarian aids (Myanmar Peace

Monitor, n.d.). So, the conflict evolved from a societal to an international level.

Multiple levels

Indeed, the rape and the initial reprisal attack are not the real source of the conflict. The

issues specific emerges from the preexisting negative relationship between the two parties

as discussed in conflict history. The root cause of the bad relationship comes from the

environment the parties find themselves subject to. Their immediate environment is filled

with mistrust, hatred, discrimination, religious intolerance, social exclusion and human rights

violations. These structural factors of the subsystem derive from broader scope of system

level dimension.

System level structure conflict appears from inequities that are built into the social system

(Dugan, 1996). According to citizenship law 1982, Rohingya cannot move out of their

residential areas without permission which limits their employment opportunities, access to

health facilities and higher education (UNHCR, 2014). They are also made to perform forced

8

labor in state-run industries and construction of model villages for non-Muslim migrants

(Simbulan, n.d.). Discrimination and submission have been deeply rooted in the

administrative, social and economic system under previous Myanmar dictators. Cultural

differences, religious differences and a weak governance system also enable acts of

discrimination (Figure 3). Thus, Dugans model reveals that structural and cultural violence

had permeated the atmosphere in the region before direct violence occurred.

Cultural aspects

The interaction between two parties of different cultures can result in miscommunication and

prolong a conflict (Bright, n.d.). An explicit divergence of religion and culture exists between

the two parties with Rohingya practicing a rigid form of Sunni Islam and speaking the

Bangalis language (The stateless Rohingya, 2012). Rakhine revere Buddhism which is a

flexible form of worship and they have their own language (South East Asia Mission Team,

2014).

Rakhine view the conflict as an attempt by Rohingya with the support of oversea religious

extremists to convert Rakhine state into an Islamic state (Inquiry Commission, 2013).

Rohingya on their side blame the communal violence on Rakhine nationalist attitudes which

see them as intolerable (Inquiry Commission, 2013). Both societies being Asian in origin

have characteristics of high context culture such as intuition, contemplation and collectivism

9

so that their communication styles are implicit and they do not emphasize logical sense.

Both sides tend to be dependent and emotion largely influences their decision-making

processes. Besides, both parties are large power distant societies and they likely to follow

their local or religious leaders. Therefore, the resentment and mistrust between the two

groups grows owing to hate speech spread by some extremist Buddhist monks (International

Crisis Group, 2013)) and imposing extremist views on every day life by extremist Imams

(Inquiry Commission, 2013). Regarding their orientation to time, Rakhine are preoccupied on

the past leaving them feeling insecure whilst Rohingya are focused upon the future leaving

them feeling frustrated with being stateless and deprivation of human rights.

Behavioral determinants

Many of Rakhine were disenchanted with corruption amongst civil servants which allowed

Rohingya to illegally farm and obtain citizenship, which Rakhine perceived as a threat to

their security (Inquiry Commission, 2013). Adding to this was many Rohingya received

temporary voting rights for 2010 general election, many Rakhine were incensed that non-

citizens were allowed to vote.

On the flip side Rohingya were frustrated with loss of citizenship and discrimination,

consequently they were not eligible to farm and fish so they became day laborers or had to

rent land (Inquiry Commission, 2013). This relative deprivation created hostility of Rohingya

toward Rakhine.

Reviewing the conflict context, the communal violence between the two groups has drawn

international attention. Although the violence is visible, it is not easy to see the underlying

attitudes and beliefs resulting from cultural and structural inequalities which drive the

violence.

10

Party orientation

Determining issues and objectives

Primary generating factors and other contributing factors can be identified by using Moores

Circle of Conflict (Bright, n.d.). The Rakhine-Rohingya conflict can be analyzed by using

Moores model (Figure 4).

Structure conflict: Demographically, Rakhine and other ethnicities constitute 80-90 percent

of population in middle and southern parts whereas Rohingya compose 90 percent of

population in north-western district (Inquiry Commission, 2013). Although agriculture and

fishery are the states main economy, majority of both groups live below poverty line.

However, Rohingya suffer more than Rakhine because they lack of citizenship rights.

Additionally, Rakhine have larger power currencies than Rohingya.

Relational conflict: Past resentment and different religions generate negative attitudes

towards each other. Both groups passed their bitterness from generation to generation

(Inquiry Commission, 2013). Consequently these attitudes make both groups assume the

other is evil. The recent violence indicates that the bitterness and hatred between two

groups are stronger than ever (Inquiry Commission 2013).

Data conflict: Information censorship and lack of transparency generate misinformation and

misinterpretation. Eventually instigators are able to inflame the situation which leads to

violence. Inquiry Commission (2013) reported that vast majority of Rakhine believed the

violence was caused by Rohingyas effort to take over Rakhine state. In the same report,

majority of Rohingya had not heard the rape case except ten Muslims being killed by a

Rakhine mob.

Interest conflict: Rakhine assume Rohingya are unwelcome economic immigrants and

want to see them leave Rakhine state (Inquiry Commission, 2013). Distrust and fear of

Rohingya and anxiety over their future exist among Rakhine (Inquiry Commission, 2013). On

the other hand, Rohingya nationalists argue that they are indigenous Muslims with deeply

rooted in Rakhine (Fennell, 2013, p. 32). They demand citizenship and for an autonomous

region in north-western part of the state (Inquiry Commission, 2013).

Values conflict: Both parties have different values with different cultures and religions.

Rakhine hold freedom and view Muslims as evil and strongly articulate that Rakhine state is

only for Rakhine people (Inquiry Commission, 2013). Being Muslims, Rohingya do not want

to mingle with non-Muslims and consider it haram (Muslims Worldwide, 2013). Rohingya

11

also believe in Sharia law which makes Rakhine more anxious and fear a threat to their

freedom and own-rights (Fennell, 2013, p. 35).

Basic Human Needs: Both parties are frustrated and concerned about loss of their identity

and security. Rakhine believe that violent attacks were caused by Rohingyas attempts to

control the land and economy of the region whereas Rohingya suppose that denial of

citizenship, Rakhines nationalist attitude and discrimination yield conflict. The assumptions

on both sides show they are preoccupied with perceived loss of their identity and security.

So, the responses during the communal conflicts are aggressive and defensive.

Therefore poverty, discriminatory laws, historical negative relationship, and rumors are main

drivers for the conflict.

12

Conflict dynamics

Conflict dynamic constitutes actions and reactions of parties, as well as events that these

actions provoke or dissuade (Bright, n.d.).

Behavior styles

The conflict style of both parties can be categorized as competing. It is characterized by

reciprocal attacks, burning, killings and physical violence. Both sides have not shown any

signal for compromising and collaborating yet. They are confronting each other and want to

get what they desire as a zero-sum (Figure 5).

Conflict events

According to Inquiry Commission (2013), the precipitating event the rape and murder case

on 28 May 2012 triggered the first phase of communal violence. Then the revenge attack

killing ten Muslims travelers followed on 3 June 2012. These events escalated to manifest

conflict process.

On 8 June, 2012, Muslims demonstrated against the killing of Muslims travelers and

attacked Buddhists houses in north-western Rakhine state (Fennell, 2013). On 12 June,

Rakhine mobs assailed Muslims houses in the state capital (Fennell, 2013). Afterwards, the

13

violence spread to other areas and continued to happen until October, 2012. These events

show transition from manifest conflict to aggressive manifest conflict state. And it escalates

in reciprocal nature.

Afterwards, negative stereotypes, fear and misperception generated pre-emptive anti-

Muslims campaigns nationwide. 969 movement is the archetype and led by extreme

nationalist Buddhist monks. Later, with the support of local authorities, Rakhine political

leaders and Buddhist monks, the conflict moved to an extreme position such as a call for

Rohingya removal from the country (Human Rights Watch, 2013). Some moderate Muslims

informed the commission that some mosques in Yangon sent Imams to proselytize and

spread their extremist views (Inquiry Commission, 2013). Eventually, both sides moved

towards extreme positions and become polarized.

Action-Reaction process

In a conflict, escalation results from a vicious circle of action and reaction (Maiese, 2003).

The homicidal rape case triggers retaliation of killing Muslims travelers. Then Muslims in

north-western part of Rakhine induce violent attack on properties of Rakhine and other

Buddhists. Eventually the violence detonates widespread sectarian violence throughout the

state with the involvement of secondary parties like Buddhist monks, and other ethnic

Buddhists (Figure 6).

Furthermore, combination of hostility towards Rohingya and anti-Muslim stereotypes forged

Rakhine as aggressors and Rohingya, stateless people as defenders. So an interpersonal

level criminal case causes aggressive response of Rakhine and other side reacts as a

defender. The defense results in the aggressors becoming more aggressive.

This results in both parties holding the perception that the behavior of the opponent is

unjustified whilst their sides behavior is justified. The mistrust, hatred and misperception

between two groups produce mirror-image responses.

Negative stereotypes and negative mirror-imaging of both parties lead to a self-fulfilling

prophecy. In a survey conducted by Inquiry Commission (2013), Rakhine reported that they

forcefully stopped Rohingyas attempts to dominate them based on their pre-formed

perception of plotting to control the state capital whereas Rohingya believe they are under

unprovoked hostile attack. So, they responded by vigorously defending themselves, this

forceful response confirms Rakhines misperception.

14

In the dynamic analysis, both parties are competing and a spiral of retaliation produces

socioeconomic changes such as loss of lives and property. Furthermore, it increases

motivation for continued conflict and negative perception through mutual violence.

15

Conflict intervention

Based on the analysis of the conflict, it is necessary to formulate a possible intervention.

From the analysis, three models are important in developing preparatory decisions. The first

one is continuum of relationship. Both parties have negative relationship along their history

and at present, both groups are contending with each other and mutual fighting and killing

still occur in places where there is no rule of law. The second model is level of conflict; it has

moved from societal level to a sectarian conflict with broader involvement of other Buddhists

and Muslims communities. Moreover, it has drawn the attention of neighboring and western

countries as well as international organizations. As per Dugans nested theory, legal system,

weak governance and cultural differences at the system level cause discrimination and

submission and human right violation of Rohingya. At the subsystem level structural

inequalities contributing are racism and mistrust.

In the intervention design menu, there are three preparatory decisions which are; track, type

of peace and timing and sequencing. Although issue specific direct violent attacks are

controlled, the situation is in the ill-state so that it is difficult to return to well-state by self-

restoration alone. As a first step, development of negative peace is necessary to alleviate

tension and hostile environment and then, positive peace should follow to tackle structural

inequalities at system and subsystem levels.

The competitive nature of conflict, track-one will work in order to implement successful

negative peace. The conflict spans multiple levels of Dugans model. Thus, during

implementing positive peace, it will require multiple interventions at political, military,

economic and cultural aspects. To achieve effective positive peace, timing and sequencing

should be considered.

After the preparatory decisions, the next step is selecting appropriate type of intervention.

During the selection, it needs to take into account expected outcomes, Dugans level to be

addressed and five categories of intervention: prevention, management, settlement,

resolution and transformation.

However, multiple interventions are required so that combination of multiple types of

intervention may be necessary. Other considerations for intervention design should include

forum, intervener roles, types of activities to pursue skills to utilize and evaluation of

satisfaction of parties involved.

16

Conclusion

The analysis shows that the conflict is complex. The bitter experiences and transferring of

resentment from one generation to another generation create mistrust and animosity

between the two groups. Besides, disparities of culture and structure between the two

groups generate discrimination and submission within the society which lead to negative

relationship. Meanwhile, an issue specific explodes the tension between the two societies.

Then a spiral of retaliation results in negative psychological and socioeconomic impact.

Poverty and the discriminatory law cause deprivation of basic human needs within the both

societies. Meanwhile, corruption, inefficient administration and political maneuvering raise

uncertainty and perceived threat to security. Consequently, it formed an uprising of religious

based extreme nationalist activities. As a result, the conflict has moved from communal

violence to broader sectarian conflict. Therefore the environment which both parties rely on

is in the ill-state.

The prognosis will depend on religious, community and political leaders. Negative peace

building should be the first step but positive peace development needs to follow. Track-One

diplomacy will be the appropriate option to tackle the ethno-religious conflict during negative

peace building. The government has not handled the situation effectively yet and has failed

to identify and charge the instigators who fuel the conflict on both sides especially Rakhine.

Further research and investigation are needed to identify the role being played currently by

and to be played in future by the government as at this stage two dominate views are; that it

is biased towards the Buddhists or is extremely inefficient. It may be necessary to instigate

an international reconciliation intervention if either of these views turns out to be proven.

17

References

Dugan, M., A. (1996). A Nested Theory of Conflict. A Leadership Journal: Women in

Leadership sharing the Vision, 1, 9-19. Retrieved from

http://cardata.gmu.edu/docs/teaching/TEACHING%20PLATFORM/course%20713/1

%20session/ANT17080105.pdf

Fennell, J. (2013). Rakhine state conflict analysis: An Overview of conflict dynamics at

national and state level. Retrieved from

https://www.academia.edu/4474183/Myanmar_Rakhine_State_Conflict_Analysis

Fortify Rights. (2014). Policies of Persecution: Ending Abusive State Policies against

Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar. Retrieved from

http://www.fortifyrights.org/downloads/Policies_of_Persecution_Feb_25_Fortify_Right

s.pdf

Galtung, J. (1996). Peace by Peaceful means: Peace and Conflict, Development and

Civilization. London, United Kingdom: SAGE Publication Ltd. Retrieved from

https://learnjcu.jcu.edu.au/webapps/portal/frameset.jsp?tab_tab_group_id=_312_1&u

rl=%2Fwebapps%2Fblackboard%2Fexecute%2Flauncher%3Ftype%3DCourse%26id

%3D_63224_1%26url%3D

Hill, C. (2013). Myanmar: sectarian violence in Rakhine issues, humanitarian

consequences, and regional responses. Retrieved from

http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/library/prspub/2613925/upload_binary/26

13925.pdf;fileType=application/pdf

Human Rights Watch. (2012). The Government Could Have Stopped This: Sectarian

Violence and Ensuing Abuses in Burmas Arakan State. Retrieved from

http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/burma0812webwcover_0.pdf

http://themuslimissue.wordpress.com/2013/05/05/rohingya-and-muslim-genocide-of-

buddhists-in-burma-and-bangladesh/

Human Rights Watch. (2013). All You Can Do is Pray: Crimes against Humanity and Ethnic

Cleansing of Rohingya Muslims in Burma Arakan State. Retrieved from

http://www.hrw.org/node/114872/section/1

18

Inquiry Commission, Union of Myanmar. (2013, July, 8). Final Report of Inquiry Commission

on Sectarian Violence in Rakhine State. Retrieved from

http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs15/Rakhine_Commission_Report-en-red.pdf

International Crisis Group. (2013). The Dark Side of Transition: Violence against Muslims in

Myanmar. Retrieved from http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/asia/south-east-

asia/burma-myanmar/251-the-dark-side-of-transition-violence-against-muslims-in-

myanmar.pdf

Kyaw Hsu Mon. (2013). Govt Rejects UN Calls for Rohingya Citizenship. Retrieved from

http://www.irrawaddy.org/un/govt-rejects-un-calls-rohingya-citizenship.html

Maiese, M. (2003). Beyond Intractability: Destructive Escalation. Retrieved from

http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/escalation

Muslims Worldwide. (2013). Rohingya and Muslim Genocide of Buddhists in Burma and

Bangladesh. Retrieved from

http://themuslimissue.wordpress.com/2013/05/05/rohingya-and-muslim-genocide-of-

buddhists-in-burma-and-bangladesh/

Myanmar Peace Monitor. (n.d.). Rakhine State Crisis Efforts. Retrieved from

http://www.mmpeacemonitor.org/peace-process/rakhine-state-crisis-efforts

Rubeinstein, R., E. (2003). Sources. In Cheldelin, S., Druckman, D., & Fast, L. (Eds.),

Conflict: from analysis to intervention (p. 55-67). New York, Continuum.

Sandole, D., J., D. (1998). A Comprehensive Mapping of Conflict and Conflict Resolution: A

Three Pillar Approach. Retrieved from

https://learnjcu.jcu.edu.au/webapps/portal/frameset.jsp?tab_tab_group_id=_312_1&u

rl=%2Fwebapps%2Fblackboard%2Fexecute%2Flauncher%3Ftype%3DCourse%26id

%3D_63224_1%26url%3D

Simbulan, K., P. (n.d.). A Legal and Structural Analysis of the Violence in Rakhine State

against the RohingyaMuslims of Myanmar. Retrieved from

https://www.academia.edu/6101564/Legal_and_Structural_Analysis_of_Violence_in_

Rakhine_State_against_the_Rohingya_Muslims_of_Myanmar

19

South East Asia Mission Team. (2014). Rakhine (Arakanese) People Group. Retrieved from

http://www.seamist.org/rakhine.php

Tillett, G., & French, B. (2006). Resolving Conflict: A Practical Approach. New York: Oxford

University Press.

The Stateless Rohingya. (2012). Rohingya: The Most Persecuted People. Retrieved from

http://www.thestateless.com/p/language.html

UNHCR. (2014). World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous People Myanmar/Burma:

Muslims and Rohingya. Retrieved from http://www.refworld.org/docid/49749cdcc.html

20

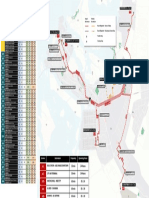

Annex 1: Rakhine-Rohingya Conflict taking place in Rakhine (Arakan) state

21

Annex 2: Map of Rakhine state showing Rakhine and Rohingya (Bangali) population

You might also like

- The "Rohingyas", Who Are They?: The Origin of The Name "Rohingya"Document11 pagesThe "Rohingyas", Who Are They?: The Origin of The Name "Rohingya"Peaceful Arakan100% (3)

- Arakan October IssueDocument16 pagesArakan October IssueArakan Rohingya National Org.No ratings yet

- On The Origins of Wahhābism PDFDocument12 pagesOn The Origins of Wahhābism PDFistanbul1453No ratings yet

- Durood NariyaDocument5 pagesDurood NariyaIrfan100% (1)

- (Abigail Jacobson) From Empire To Empire Jerusale PDFDocument281 pages(Abigail Jacobson) From Empire To Empire Jerusale PDFRidzki Maulana Hidayat100% (1)

- A Case Study On How and Why Rohingya Ref PDFDocument15 pagesA Case Study On How and Why Rohingya Ref PDFNipu TabasumNo ratings yet

- The Liberation War of Bangladesh: Role of The Army: June 2015Document11 pagesThe Liberation War of Bangladesh: Role of The Army: June 2015Matra LogisticsNo ratings yet

- Sand Cone Model PDFDocument34 pagesSand Cone Model PDFNyein ChanyamyayNo ratings yet

- 1947 Newspaper - Muslim DemandsDocument2 pages1947 Newspaper - Muslim DemandsRick Heizman100% (1)

- Baswedan, Anies RaysidDocument237 pagesBaswedan, Anies RaysidAudi mobaNo ratings yet

- Rohingya MuslimsDocument19 pagesRohingya MuslimsAnimesh GuptaNo ratings yet

- Burden to Strength ProverbsDocument16 pagesBurden to Strength ProverbsNyein Chanyamyay100% (1)

- Glossary of ManufacturingDocument273 pagesGlossary of Manufacturingokamo100% (6)

- EPA Full ReportDocument278 pagesEPA Full ReportSir TemplarNo ratings yet

- Collateral Usage Cooperation Agreement: Number: / - d'P/I/2021Document7 pagesCollateral Usage Cooperation Agreement: Number: / - d'P/I/2021isbbjnNo ratings yet

- 2001 National Household Travel Survey User's GuideDocument820 pages2001 National Household Travel Survey User's GuideMike GordonNo ratings yet

- Sutan Sjahrir and The Failure of Indonesian SocialismDocument23 pagesSutan Sjahrir and The Failure of Indonesian SocialismGEMSOS_ID100% (2)

- Special Report On Violence Against Indigenous Jumma in The Chittagong Hill TractsDocument29 pagesSpecial Report On Violence Against Indigenous Jumma in The Chittagong Hill TractsJusticeMakersBDNo ratings yet

- An Assignment On Contribution of Japan To Liberation WarDocument7 pagesAn Assignment On Contribution of Japan To Liberation WarMubin Afridi100% (1)

- Inspection Checklist For LYCODocument22 pagesInspection Checklist For LYCODavid DoughtyNo ratings yet

- Rohingya - The History of A Muslim Identity in Myanmar by Jacques LeiderDocument38 pagesRohingya - The History of A Muslim Identity in Myanmar by Jacques LeiderInformerNo ratings yet

- The Star: News Piece On The Ruth First Mural.Document1 pageThe Star: News Piece On The Ruth First Mural.Shafiur RahmanNo ratings yet

- The Historic 7Th March Speech of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur RahmanDocument31 pagesThe Historic 7Th March Speech of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur RahmanSanzid Ahmed ShaqqibNo ratings yet

- Tribal (Aadibashi) Women in BangladeshDocument11 pagesTribal (Aadibashi) Women in BangladeshDr. Khan Sarfaraz Ali40% (5)

- Jamaat Upholds Action To Crush Armed RebellionDocument4 pagesJamaat Upholds Action To Crush Armed RebellionARFoundationNo ratings yet

- Plight of Rohingyas HistoricityDocument3 pagesPlight of Rohingyas HistoricitymayunadiNo ratings yet

- Complete Index of Writers from the Marxists Internet Archive LibraryDocument22 pagesComplete Index of Writers from the Marxists Internet Archive LibraryRodri RojasNo ratings yet

- Civil Military Relations in Bangladesh-PriDocument7 pagesCivil Military Relations in Bangladesh-PriShaheen AzadNo ratings yet

- The MOU Between Myanmar Government and UNDP and UNHCRDocument10 pagesThe MOU Between Myanmar Government and UNDP and UNHCRFree Rohingya Coalition100% (1)

- Conflict Mapping Rakhine Rohingya ConfliDocument22 pagesConflict Mapping Rakhine Rohingya ConfliM Munour RashidNo ratings yet

- Sarah Syed Myanmar Policy BriefDocument25 pagesSarah Syed Myanmar Policy BriefAnonymous AVSeo9100% (2)

- For International Conference On RohingyaDocument10 pagesFor International Conference On RohingyachetnaNo ratings yet

- CS8 Panteion II Rohingya The Invisible Minority of MyanmarDocument6 pagesCS8 Panteion II Rohingya The Invisible Minority of MyanmarDanai LamaNo ratings yet

- Konflik Di Rohingya: Hubungannya Dengan Umat Islam Sejagat: OriginDocument5 pagesKonflik Di Rohingya: Hubungannya Dengan Umat Islam Sejagat: OriginANo ratings yet

- Elements of Pathos and Media Framing As Scientific DiscourseDocument11 pagesElements of Pathos and Media Framing As Scientific DiscourseNAEEM AFZALNo ratings yet

- Arts and Social Sciences Journal: Systematic Ethnic Cleansing: The Case Study of RohingyaDocument7 pagesArts and Social Sciences Journal: Systematic Ethnic Cleansing: The Case Study of RohingyaArafat jamilNo ratings yet

- Rohingya Issue More Economic Than Identity Crisis or Religious'Document11 pagesRohingya Issue More Economic Than Identity Crisis or Religious'akar phyoeNo ratings yet

- History of Rakhine State and The Origin of The Rohingya MuslimsDocument28 pagesHistory of Rakhine State and The Origin of The Rohingya MuslimsArafat jamilNo ratings yet

- Rohingya Refugees and Socio-Cultural PsychologyDocument63 pagesRohingya Refugees and Socio-Cultural PsychologyAnoushka GhoshNo ratings yet

- Myanmar 'S Worsening Rohingya Crisis: A Call For Responsibility To Protect and ASEAN 'S ResponseDocument14 pagesMyanmar 'S Worsening Rohingya Crisis: A Call For Responsibility To Protect and ASEAN 'S ResponseCiy EfijNo ratings yet

- "The Government Could Have Stopped This": Sectarian Violence and Ensuing Abuses in Burma's Arakan StateDocument62 pages"The Government Could Have Stopped This": Sectarian Violence and Ensuing Abuses in Burma's Arakan StateKhin SweNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Rohingyas As Stateless Ethnic Community: BstractDocument13 pagesEvolution of Rohingyas As Stateless Ethnic Community: Bstractsubhashni kumariNo ratings yet

- The Rohingya CrisisDocument8 pagesThe Rohingya CrisisMishkatul FerdousNo ratings yet

- Ethnic CleansingDocument8 pagesEthnic CleansingNicole SesaldoNo ratings yet

- Policy Paper FinalDocument9 pagesPolicy Paper FinalFuhad HasanNo ratings yet

- E Portfolio AssignmentDocument7 pagesE Portfolio Assignmentapi-316949889No ratings yet

- Myanmar's Buddhist Burmese Chauvinism Implications On Rohingya Humanitarian CrisisDocument8 pagesMyanmar's Buddhist Burmese Chauvinism Implications On Rohingya Humanitarian CrisisNahian SalsabeelNo ratings yet

- Ongoing Genocidal Crisis of the Rohingya MinorityDocument21 pagesOngoing Genocidal Crisis of the Rohingya Minoritysewisah66No ratings yet

- International relationsDocument8 pagesInternational relationspoovizhikalyani.m2603No ratings yet

- Strategic Denial of Rohingya Identity and Their Right To Internal Self-DeterminationDocument18 pagesStrategic Denial of Rohingya Identity and Their Right To Internal Self-DeterminationPedro Lucas de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Traumatized Victims and Mutilated Bodies: Human Rights and The Politics of Immediation' in The Rohingya Crisis of Burma/MyanmarDocument18 pagesTraumatized Victims and Mutilated Bodies: Human Rights and The Politics of Immediation' in The Rohingya Crisis of Burma/Myanmarakar phyoeNo ratings yet

- The Rohingyas of MyanmarDocument8 pagesThe Rohingyas of MyanmarMohd Mahathir SuguaNo ratings yet

- Advance Edited Version: Situation of Human Rights of Rohingya Muslims and Other Minorities in MyanmarDocument19 pagesAdvance Edited Version: Situation of Human Rights of Rohingya Muslims and Other Minorities in MyanmarKushar Dev ChhibberNo ratings yet

- Displacement of The Rohingyas in Southeast AsiaDocument20 pagesDisplacement of The Rohingyas in Southeast AsiatrinitaNo ratings yet

- Rohingya CrisisDocument3 pagesRohingya CrisisMuhammad Ridho Al HafizNo ratings yet

- Truth & Rights: Statelessness, Human Rights, and The RohingyaDocument11 pagesTruth & Rights: Statelessness, Human Rights, and The RohingyaSaiful Islam SohanNo ratings yet

- Rohingyan CrisisDocument7 pagesRohingyan CrisisAhsan SeedNo ratings yet

- Indonesia's Role in Rohingya CrisisDocument2 pagesIndonesia's Role in Rohingya CrisisIdham Rizky YudantoNo ratings yet

- Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army: Not The Jihadis You Might ExpectDocument3 pagesArakan Rohingya Salvation Army: Not The Jihadis You Might ExpectlaeeeqNo ratings yet

- Pol VivaDocument3 pagesPol Vivasuman gothwalNo ratings yet

- Rohingya ConflictDocument3 pagesRohingya ConflictAlfa WolfNo ratings yet

- Rohingya Crisis: Present Status and Potential SolutionsDocument20 pagesRohingya Crisis: Present Status and Potential SolutionsMoumita SarkarNo ratings yet

- Rohingyas: The Stateless-: Have Been Called The "World's Most Persecuted Minority"Document8 pagesRohingyas: The Stateless-: Have Been Called The "World's Most Persecuted Minority"sharikaNo ratings yet

- 2017-08-25-Abandoned and Apartheid A Case Study of Rohingya-En-redDocument19 pages2017-08-25-Abandoned and Apartheid A Case Study of Rohingya-En-redHtet AaronNo ratings yet

- FinalMainDocument BUDocument45 pagesFinalMainDocument BUEmam MursalinNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Drug Resistant Malaria Lancet PDFDocument11 pagesEpidemiology of Drug Resistant Malaria Lancet PDFNyein ChanyamyayNo ratings yet

- Accenture Outlook Digitizing Value Chain COFCO China PDFDocument2 pagesAccenture Outlook Digitizing Value Chain COFCO China PDFNyein ChanyamyayNo ratings yet

- Reflective WritingDocument2 pagesReflective WritingNyein ChanyamyayNo ratings yet

- Case Study Assignment Managing ConflictDocument13 pagesCase Study Assignment Managing ConflictNyein ChanyamyayNo ratings yet

- 05-09-2018Document58 pages05-09-2018Abdul RehmanNo ratings yet

- Hattusa, Capital of the Hittites Included in UNESCO's World Heritage ListDocument170 pagesHattusa, Capital of the Hittites Included in UNESCO's World Heritage ListRıdvan DenizelNo ratings yet

- History of The Philippines (900-1565) The History of The Philippines Between 900 and 1565Document1 pageHistory of The Philippines (900-1565) The History of The Philippines Between 900 and 1565jovelyn dahangNo ratings yet

- An Atheist's Sermon on Reason and EvidenceDocument6 pagesAn Atheist's Sermon on Reason and EvidencejdtamayoNo ratings yet

- Ifas 1 PDFDocument8 pagesIfas 1 PDFAcha BachaNo ratings yet

- Doa Sesudah SalatDocument1 pageDoa Sesudah Salatahmad2ilkom2008No ratings yet

- HALAQOH TAHFIDZDocument33 pagesHALAQOH TAHFIDZYusuf Masykur DNo ratings yet

- Major Signs Before The Day of JudgementDocument57 pagesMajor Signs Before The Day of Judgementa_mohid17No ratings yet

- A Social History of Early Arab Photogra PDFDocument32 pagesA Social History of Early Arab Photogra PDFმირიამმაიმარისიNo ratings yet

- English A Study of The Wifes Rights in Islamic FiqhDocument303 pagesEnglish A Study of The Wifes Rights in Islamic Fiqh1465146514No ratings yet

- Ibn Taymiyya Radical Polymath Part II in PDFDocument23 pagesIbn Taymiyya Radical Polymath Part II in PDFDavudNo ratings yet

- Translatio Explanati Lessons Arabic VersesDocument332 pagesTranslatio Explanati Lessons Arabic Versesalamin.tafeNo ratings yet

- Hyderabad: Nawab Mir Mahbub Ali Khan Asaf Jah VI. 1869-1911Document23 pagesHyderabad: Nawab Mir Mahbub Ali Khan Asaf Jah VI. 1869-1911Al Mamun-Or- RashidNo ratings yet

- Nadhom Asmaul Husna PDF Download PDFDocument3 pagesNadhom Asmaul Husna PDF Download PDFKang MukidiNo ratings yet

- Al - FarghaniDocument17 pagesAl - FarghaniADNo ratings yet

- Family Tree of Prophet Adam To Muhammad SawDocument2 pagesFamily Tree of Prophet Adam To Muhammad SawandreskancritNo ratings yet

- Politeness and Complimenting Within An Algerian Context - A Socio-Pragmatic AnalysisDocument14 pagesPoliteness and Complimenting Within An Algerian Context - A Socio-Pragmatic AnalysisGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Afghan Detainee Documents - CSC/SAMPIS Files (Part 1)Document632 pagesAfghan Detainee Documents - CSC/SAMPIS Files (Part 1)kady_omalley5260No ratings yet

- Azaan Aur Iqamat Ka BayanDocument5 pagesAzaan Aur Iqamat Ka BayanAbdul MajidNo ratings yet

- Circular Visions of Fertility and Punishment: Caliphal Ivory Caskets From Al-AndalusDocument24 pagesCircular Visions of Fertility and Punishment: Caliphal Ivory Caskets From Al-AndalusJuanna PerezNo ratings yet

- Arab-Zionist Entente 1913-1914Document31 pagesArab-Zionist Entente 1913-1914fauzanrasipNo ratings yet

- Edinburgh Research Explorer: Cyclical History in The Gambia/Casamance BorderlandsDocument24 pagesEdinburgh Research Explorer: Cyclical History in The Gambia/Casamance BorderlandsalexNo ratings yet

- Neighborhood Family DramaDocument67 pagesNeighborhood Family DramaoninebuenrNo ratings yet

- Abu Dhabi Airport Bus Schedule and Route Map 2019Document1 pageAbu Dhabi Airport Bus Schedule and Route Map 2019Desai NileshNo ratings yet

- Shirk K Chor DarwazeDocument382 pagesShirk K Chor DarwazeIslamic Reserch Center (IRC)No ratings yet

- Sūrat Al-Nisā and The Centrality of Justice: Raymond K. FarrinDocument17 pagesSūrat Al-Nisā and The Centrality of Justice: Raymond K. FarrinSo' FineNo ratings yet

- Yasir QadhiDocument2 pagesYasir Qadhiaejaz87No ratings yet