Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Transpo Day 1 Cases

Uploaded by

Jasmin AlapagCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Transpo Day 1 Cases

Uploaded by

Jasmin AlapagCopyright:

Available Formats

FIRST PHILIPPINE INDUSTRIAL CORPORATION vs.

COURT OF APPEALS

Facts: Petitioner is a grantee of a pipeline concession under RA 387 to contract, install and operate oil pipelines. The

first pipeline concession was granted in 1967 and was renewed by the ERB in 1992. In 1995, petitioner applied for a

Mayors permit in Batangas City. Respondent treasurer required petitioner to pay a local tax based on its gross

receipts for the fiscal year in 1993 pursuant to the Local Government Code.

To avoid hampering its operations, petitioner paid the amount of tax for the first quarter under protest.

Petitioner argued that as a pipeline operator with a government concession engaged in transporting petroleum

products via pipeline it is exempted from payment of tax based on gross receipts. Respondent refused to make

reimbursement on the ground that petitioner is not a common carrier engaged in transportation business by land,

water or air.

Issue: Whether or not petitioner is liable to pay a local tax based on gross receipts since it is not a common carrier.

Held: No. Based on Article 1732 NCC, there is no doubt that petitioner is a common carrier. It is engaged in the

business of transporting or carrying goods, i.e. petroleum products, for hire as a public employment. It undertakes to

carry for all persons indifferently, that is, to all persons who choose to employ its services, and transports the goods

by land and for compensation. The fact that petitioner has a limited clientele does not exclude it from the definition of

a common carrier. (De Guzman Ruling upheld)

Respondents argument that the term common carrier as used in Section 133(j) of the Local Government

Code refers only to common carriers transporting goods and passengers through moving vehicles or vessels either

by land, sea or water is erroneous. The definition of common carriers in NCC makes no distinction as to the means

of transporting as long as it is by land, water or air. It does not provide that the transporting of the passengers or

goods should be by motor vehicle.

It is clear that the legislative intent in excluding from the taxing power of the local government unit the

imposition of business tax against common carriers is to prevent a duplication of the so-called "common carrier's tax."

Petitioner is already paying 3% common carrier's tax on its gross sales/earnings under the National Internal Revenue

Code. To tax petitioner again on its gross receipts in its transportation of petroleum business would defeat the

purpose of the Local Government Code.

DE GUZMAN vs. COURT OF APPEALS

Facts: Respondent Ernesto Cendaa is a junk dealer who was engaged in buying up used bottles and scrap metal in

Pangasinan. Upon gathering sufficient quantities of such scrap material, respondent would bring such material to

Manila for resale. He utilized two six-wheeler trucks which he owned for hauling the material to Manila. On the return

trip to Pangasinan, respondent would load his vehicles with cargo which various merchants wanted delivered to

different establishments in Pangasinan. For that service, respondent charged freight rates which were commonly

lower than regular commercial rates.

Petitioner Pedro de Guzman a merchant and authorized dealer of General Milk Company (Philippines), Inc.

in Urdaneta, Pangasinan, contracted with respondent for the hauling of 750 cartons of Liberty filled milk from its

warehouse in Makati to petitioner's establishment in Urdaneta. 150 cartons were loaded on a truck driven by

respondent, while 600 cartons were placed on board the other truck which was driven by Manuel Estrada,

respondent's driver and employee. Only 150 boxes of Liberty filled milk were delivered to petitioner. The other 600

boxes never reached petitioner, since the truck which carried these boxes was hijacked somewhere along the

MacArthur Highway in Paniqui, Tarlac, by armed men who took with them the truck, its driver, his helper and the

cargo.

Petitioner commenced action against private respondent demanding payment of P22,150.00, the claimed

value of the lost merchandise, plus damages and attorney's fees. Petitioner argued that private respondent, being a

common carrier, and having failed to exercise the extraordinary diligence required of him by the law, should be held

liable for the value of the undelivered goods. Private respondent denied that he was a common carrier and argued

that he could not be held responsible for the value of the lost goods, such loss having been due to force majeure.

The RTC ruled that private respondent was a common carrier. CA reversed the decision and held that

respondent had been engaged in transporting return loads of freight "as a casual occupation, a sideline to his scrap

iron business.

Issue: 1. Whether or not respondent is a common carrier.

2. Whether or not respondent is liable.

Held: 1. Yes. Article 1732 makes no distinction between one whose principal business activity is the carrying of

persons or goods or both, and one who does such carrying only as an ancillary activity (in local Idiom as "a sideline").

Article 1732 also carefully avoids making any distinction between a person or enterprise offering transportation

service on a regular or scheduled basis and one offering such service on an occasional, episodic or unscheduled

basis. Neither does Article 1732 distinguish between a carrier offering its services to the "general public," i.e., the

general community or population, and one who offers services or solicits business only from a narrow segment of the

general population.

The Court of Appeals referred to the fact that private respondent held no certificate of public convenience. A

certificate of public convenience is not a requisite for the incurring of liability. That liability arises the moment a person

or firm acts as a common carrier, without regard to whether or not such carrier has also complied with the

requirements of the applicable regulatory statute and implementing regulations and has been granted a certificate of

public convenience or other franchise. To exempt private respondent from the liabilities of a common carrier because

he has not secured the necessary certificate of public convenience, would be offensive to sound public policy; that

would be to reward private respondent precisely for failing to comply with applicable statutory requirements.

2. No. Article 1734 establishes the general rule that common carriers are responsible for the loss, destruction or

deterioration of the goods which they carry, "unless the same is due to any of the following causes only:

(1) Flood, storm, earthquake, lightning or other natural disaster or calamity;

(2) Act of the public enemy in war, whether international or civil;

(3) Act or omission of the shipper or owner of the goods;

(4) The character-of the goods or defects in the packing or-in the containers; and

(5) Order or act of competent public authority.

Article 1735 also provides as follows:

In all cases other than those mentioned in numbers 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 of the preceding article, if the goods are lost,

destroyed or deteriorated, common carriers are presumed to have been at fault or to have acted negligently, unless

they prove that they observed extraordinary diligence as required in Article 1733.

The hijacking of the carrier's truck does not fall within any of the five categories of exempting causes listed in Article

1734. It would follow, therefore, that the hijacking of the carrier's vehicle must be dealt with under the provisions of

Article 1735, in other words, that the private respondent as common carrier is presumed to have been at fault or to

have acted negligently. This presumption, however, may be overthrown by proof of extraordinary diligence on the

part of private respondent. Petitioner argues that in the circumstances of this case, private respondent should have

hired a security guard presumably to ride with the truck carrying the 600 cartons of Liberty filled milk. We do not

believe, however, that in the instant case, the standard of extraordinary diligence required private respondent to

retain a security guard to ride with the truck and to engage brigands in a firelight at the risk of his own life and the

lives of the driver and his helper.

Article 1745 provides in relevant part:

Any of the following or similar stipulations shall be considered unreasonable, unjust and contrary to public policy:

(6) that the common carrier's liability for acts committed by thieves, or of robbers who do not act with grave

or irresistible threat, violence or force, is dispensed with or diminished.

In the instant case, armed men held up the second truck owned by private respondent which carried

petitioner's cargo. Accused acted with grave, if not irresistible, threat, violence or force. In these circumstances, we

hold that the occurrence of the loss must reasonably be regarded as quite beyond the control of the common carrier

and properly regarded as a fortuitous event. It is necessary to recall that even common carriers are not made

absolute insurers against all risks of travel and of transport of goods, and are not held liable for acts or events which

cannot be foreseen or are inevitable, provided that they shall have complied with the rigorous standard of

extraordinary diligence.

PLANTERS PRODUCTS, INC. vs. COURT OF APPEALS

Facts: PPI purchased from Mitsubishi metric tons of Urea fertilizer which the latter shipped aboard the cargo vessel

owned by KKKK from US to La Union. Prior to its voyage, a time charter-party on the vessel was entered into

between Mitsubishi as shipper/charterer and KKKK as shipowner, in Tokyo, Japan. Before loading the fertilizer

aboard the vessel, they were all presumably inspected by the charterer's representative and found fit to take a load of

urea. After the Urea fertilizer was loaded in bulk by stevedores hired by and under the supervision of the shipper, the

steel hatches were closed with heavy iron lids, covered with three layers of tarpaulin, then tied with steel bonds. The

hatches remained closed and tightly sealed throughout the entire voyage.

A private marine and cargo surveyor, Cargo Superintendents Company Inc. (CSCI), was hired by PPI to

determine the "outturn" of the cargo shipped. The survey report submitted revealed a shortage in the cargo and that

a portion of the Urea fertilizer approximating was contaminated with dirt.

PPI sent a claim letter to Soriamont Steamship Agencies (SSA), the resident agent of the carrier, KKKK, for

the cost of the shortage in the and the diminution in value of that portion contaminated with dirt. SSA explained that

they did not respond to the consignee's claim because it was not a formal claim, and that they had nothing to do with

the discharge of the shipment.

PPI filed an action for damages. The defendant carrier argued that the strict public policy governing

common carriers does not apply to them because they have become private carriers by reason of the provisions of

the charter-party. RTC ruled in favor of plaintiff, stating that common carriers are presumed negligent, all that a

shipper has to do in a suit to recover for loss or damage is to show receipt by the carrier of the goods and to delivery

by it of less than what it received. After that, the burden of proving that the loss or damage was due to any of the

causes which exempt him from liability is shifted to the carrier, common or private he may be. Even if the provisions

of the charter-party are deemed valid, and the defendants considered private carriers, it was still incumbent upon

them to prove that the shortage or contamination sustained by the cargo is attributable to the fault or negligence on

the part of the shipper or consignee in the loading, stowing, trimming and discharge of the cargo. This they failed to

do. CA reversed the decision, relying on the 1968 case of Home Insurance Co. v. American Steamship Agencies,

Inc., it ruled that the cargo vessel M/V "Sun Plum" owned by private respondent KKKK was a private carrier and not a

common carrier by reason of the time charterer-party. Accordingly, the Civil Code provisions on common carriers

which set forth a presumption of negligence do not find application in the case at bar.

Issue: 1) Whether a common carrier becomes a private carrier by reason of a charter-party.

2) Whether the shipowner was able to prove that he had exercised that degree of diligence required of him

under the law.

Held: 1.) Not necessarily. It is not disputed that respondent carrier, in the ordinary course of business, operates as a

common carrier, transporting goods indiscriminately for all persons. When petitioner chartered the vessel M/V "Sun

Plum", the ship captain, its officers and compliment were under the employ of the shipowner and therefore continued

to be under its direct supervision and control. Hardly then can the charterer be charged, a stranger to the crew and to

the ship, with the duty of caring for his cargo when the charterer did not have any control of the means in doing so.

This is evident in the present case considering that the steering of the ship, the manning of the decks, the

determination of the course of the voyage and other technical incidents of maritime navigation were all consigned to

the officers and crew who were screened, chosen and hired by the shipowner. It is therefore imperative that a public

carrier shall remain as such, notwithstanding the charter of the whole or portion of a vessel by one or more persons,

provided the charter is limited to the ship only, as in the case of a time-charter or voyage-charter. It is only when the

charter includes both the vessel and its crew, that a common carrier becomes private, at least insofar as the

particular voyage covering the charter-party is concerned. Indubitably, a shipowner in a time or voyage charter

retains possession and control of the ship, although her holds may, for the moment, be the property of the charterer.

Respondent carrier's heavy reliance on the case of Home Insurance Co. v. American Steamship Agencies,

is misplaced for the reason that the meat of the controversy therein was the validity of a stipulation in the charter-

party exempting the shipowners from liability for loss due to the negligence of its agent, and not the effects of a

special charter on common carriers. At any rate, the rule in the United States that a ship chartered by a single

shipper to carry special cargo is not a common carrier, does not find application in our jurisdiction, for we have

observed that the growing concern for safety in the transportation of passengers and /or carriage of goods by sea

requires a more exacting interpretation of admiralty laws, more particularly, the rules governing common carriers.

2.) Yes. In an action for recovery of damages against a common carrier on the goods shipped, the RTCs statement

on the requirements of the law was reiterated. SC held that respondent carrier has sufficiently overcome, by clear

and convincing proof, the prima facie presumption of negligence.

It was shown during the trial that after the loading of the cargo in bulk in the ships holds, the steel pontoon

hatches were closed and sealed with iron lids, then covered with 3 layers of serviceable tarpaulins which were tied

with steel bonds. The hatches remained close and tightly sealed while the ship was in transit as the weight of the

steel covers made it impossible for a person to open without the use of the ships boom. Also shown, was that the

hull of the vessel was in good condition, foreclosing the possibility of spillage of the cargo into the sea or seepage of

water inside the hull of the vessel.

SC agreed that the bulk shipment of highly soluble goods like fertilizer carries with it the risk of loss or

damage. Moreso, with a variable weather condition prevalent during its unloading, as was the case at bar. This is a

risk the shipper or the owner of the goods has to face. Clearly, respondent carrier has sufficiently proved the inherent

character of the goods which makes it highly vulnerable to deterioration; as well as the inadequacy of its packaging

which further contributed to the loss.

II. CONTRACTUAL EFFECTS

A. Vigilance over Goods

GELISAN vs. ALDAY

Facts: Bienvenido Gelisan is the owner of a freight truck. Defendant Bienveido Gelisan and Roberto Roberto entered

into a contact underwhich Espiritu hired the same freight truck of Gelisan for the purpose of hauling rice, sugar, flour

and fertilizer. It also agreed that Espiritu shall bear and pay all losses and damages attending the carriage of the

goods to be hauled by him.

Benito Alday, a trucking operator had known Roberto Espiritu. Alday had a contact to haul the fertilizer of

the Atlas Fertilizer Corporation from Pier 4, North Harbor, to its Warehouse in Mandaluyong.

Alday met Espiritu at the gate of Pier 4 and the latter offered the use of his truck with the driver and helper.

The offer was accepted by Alday and he instructed his checker to let Roberto Espiritu haul the fertilizer. Espiritu

made two hauls of zoobags of fertilizer per trip. The fertilizer was delivered to the driver and helper of Espiritu with

the necessary waybill receipts. Espiritu, however, did not deliver the fertilizer to the Atlas Fertilizer bodega at

Mandaluyong.

Thus, Benito Alday was compelled to pay the value of the 400 bags of fertilizers to Atlas Fertilizer

Corporation and filed a compliant against Roberto Espiritu and Bienvenido Gelisan with the CFI of Manila.

The CFI of Manila ruled that Roberto Espiritu was the only one liable. On appeal, CA ruled that Bienvenido

Gelisan is likewise liable for being the registered owner of the truck.

Issue: Whether or not Gelisan should be held solidarily liable with Espiritu, being the registered owner of the truck.

Held: Yes, Gelisan should be held solidarily liable with Espiritu, being the registered owner of the truck.

The Court has invariably held in several decisions that the registered owner of a public service vehicle is

responsible for damages that may arise from consequences incident to its operation or that may be caused to any of

the passengers therein. The claim of the petitioner that he is not liable in view of the lease contract executed by and

between him and Roberto Espiritu which exempts him from liability to third persons, cannot be sustained because it

appears that the lease contract, adverted to, had not been approved by the Public service Commission. It is settled in

our jurisprudence that if the property covered by a franchise is transferred or leased to another without obtaining the

requisite approval, the transfer is not binding upon the public or third persons. However, Gelisan is not without

recourse because he has a right to be indemnified by Roberto Espiritu for the amount that he may be required to pay

as damages for the injury caused to Benito Alday, since the lease contract in question, although not effective against

the public for not having been approved by the Public Service Commission, is valid and binding between the

contracting parties.

The Court ruled that the petitioner is DENIED. With costs against the petitioner.

BENEDICTO vs. IAC

Facts: Private respondent Greenhills Wood Industries Company, Inc., a lumber manufacturing firm, operates a

sawmill in Quirino.

Sometime in May 1980, private respondent bound itself to sell and deliver to Blue Star Mahogany, Inc.

(Blue Star), a company in Bulacan 100,000 board feet of sawn lumber with the understanding that an initial delivery

would be made on May 15, 1980. To effect its first delivery, private respondents resident manager Dominador Cruz,

contracted Virgilio Licuden, the driver of a cargo truck to transport its sawn lumber to the consignee Blue Star in

Valenzuela, Bulacan. The cargo truck was registered in the name of petitioner Ma. Luisa Benedicto, the proprietor of

Macoren Trucking, a business enterprise engaged in hauling freight.

On May 15, 1980, cruz in the presence and with the consent of driver Licuden, supervised the loading of

sawn lumber with invoice aboard the cargo truck. Thereafter, the Manager of Blue Star called up Greenhills

president, informing him that the sawn lumber on board the subject cargo truck had not yet arrived in Bulacan. The

latter then informed Greenhills resident manager. Still, Blue Star had not received the sawn lumber and were

constrained to look for other suppliers.

Thus, private respondent Greenhills filed criminal case against driver Luciden for estafa and also against

petitioner Benedicto for recovery of the value of the lost sawn lumber plus damages before the RTC of Dagupan City.

The trial court ruled against Benedicto and Luciden. On appeal, the IAC affirmed the decision of the trial

court in toto.

Issue: Whether or not petitioner Benedicto, being the registered owner of the carrier, should be held liable for the

value of the undelivered or lost sawn lumber.

Held: Yes, Benedicto is liable for the undelivered or lost sawn lumber as registered owner. There is no dispute that

petitioner Benedicto has been holding herself out to the public as engaged in the business of hauling or transporting

goods for hire or compensation. Petitioner Benedicto is, in brief, a common carrier.

The prevailing doctrine on common carrier makes the registered owner liable for consequences flowing from

the operations of the carrier, even though the specific vehicle involved may already have been transferred to another

person. This doctrine rests upon the principle that in dealing with vehicles registered under the Public Service Law,

the public has the right to assume that the registered owner is the actual or lawful owner thereof. It would be very

difficult and often impossible as a practical matter, for members of the general public to enforce the rights of action

that they may have for injuries inflicted by the vehicles being negligently operated if they should be required to prove

who the actual owner is. The registered owner is not allowed to deny liability by proving the identity of the alleged

transferee.

In the case at bar, private respondent is not required to go beyond the vehicles certificate of registration to

ascertain the owner of the carrier. In this regard, the letter presented by petitioner allegedly written by Benjamin Tee

admitting that Licuden was his driver, had no evidentiary value not only because Benjamin Tee was not presented in

court to testify on this matter but because of the afore mentioned doctrine. To permit the ostensible or registered

owner to prove who the actual owner is, would be to set at naught the purpose or public policy which infuses that

doctrine.

The Court ruled that the Petition fro Review is Denied.

LITA ENTERPRISES, INC. vs. CA

Facts: Sometime in 1966, the spouses Nicasio Ocampo and Francisca Garcia, herein private respondent purchased

in installment from the Delta Motor Sales Corp. five Toyota Corona Standard cars to be used as taxicabs. Since they

had no franchise to operate taxicabs, they contracted with petitioner, for the use of the latters certificate of public

convenience in consideration of an initial payment of P1,000 and a monthly rental of P200 per taxi cab unit.

About a year later, one of said taxicabs driven by their employee, Emeterio Martin, collided with a

motorcycle whose driver, Florante Galvez, died from the head injuries sustained. A criminal case was filed against

the driver while a civil case was filed against Lita enterprises seeking for damages. In the CFI of Manila, petitioner

Lita Enterprises was adjudged liable for damages as the registered owner of the taxicab. Thus, a writ of execution

was issued and one of the vehicles of respondent spouses was levied upon and sold at public auction.

Thereafter, respondent Nicasio Ocampo decided to register his taxicab in his name, but Lita Enterprises

allegedly refused. Hence, the spouses filed a complaint. The CFI of Manila ordered Lita Enterprises to transfer the

registration certificate. On Appeal, the IAC modified the decision.

Issue: Whether or not the parties entered into a kabit system

Held: Yes, the parties entered into a kabit system. The parties herein operated under an arrangement, commonly

known as the kabit system, whereby a person who has been granted a certificate of convenience allows another

person who owns motor vehicles to operate under such franchise for a fee. A certificate of public convenience is a

special privilege conferred by the government. Abuse of this privilege by the grantees thereof cannot be

countenanced. The kabit system has been identified as one of the root causes of the prevalence of graft and

corruption in the government transportation services. Thus, the concept of Kabit system being contrary to public

policy and void and existent, the court cannot allow either of the parties to enforce an illegal contract bu leaves them

both where it finds them.

The Court ruled that the decisions rendered by the CFI of Manila and IAC are hereby annulled and set

aside.

TEJA MARKETING vs. IAC

Facts: On May 9, 1975, the defendant bought from the plaintiff a motorcycle with complete accessories and a

sidecar in the total consideration of P8,000.00. Out of the total purchase price the defendant gave a down payment

of P1,700.00 with a promise that he would pay plaintiff the balance within sixty days. The defendant, however, failed

to comply with his promise and so upon his own request, the period of paying the balance was extended to one year

in monthly installments until January 1976 when he stopped paying anymore. The plaintiff made demands but just

the same the defendant failed to comply thus forcing plaintiff to consult a lawyer and file this action for his damage.

It also appears and the court so finds that the defendant purchased the motorcycle in question and the

Court so finds that defendant purchased the motorcycle in question, particularly for the purpose of engaging and

using the same in transportation business and for this purpose said trimobile unit was attached to the plaintiffs

transportation line who had the franchise, so much so that in the registration certificate, the plaintiff appears to be the

owner of the unit. Furthermore, it appears to have been agreed further between, the plaintiff and the defendant, that

plaintiff would undertake the yearly registration of the unit in question with the LTC. Thus, for the registration of the

unit for the year 1976, per agreement, the defendant gave to the plaintiff the amount of P82.00 of rits registration, as

well as the insurance coverage of the unit.

Petitioner Teja Marketing and/or Angel Jaucian filed an action for the sum of money with damages. The

city court rendered judgment in favor of petitioner. On appeal, the decision was affirmed in toto.

Issue: Whether or not kabit system applies in the instant case.

Held: Yes, the parties operated under an agreement called kabit system. This is a system whereby a person who

has been granted a certificate of public convenience allows another person who owns motor vehicles to operate

under such franchise for a fee. A certificate of public convenience is a special privilege conferred by the government.

Although not outrightly penalized as a criminal offense, the kabit system is invariably recognized as being contrary to

public policy and therefore, void and inexistent under Article 1404 of the Civil Code. Thus, court will not aid either

party to enforce an illegal contract, but will leave both where it finds them.

The court ruled that the petition is hereby dismissed for lack of merit. The assailed decision of the IAC now

the CA is AFFIRMED.

MAGBOO vs. BERNARDO

Facts: The spouses Magboo are the parents of the 8-year old child killed in a motor vehicle accident, the vehicle

owned by the defendant Bernardo. At the time of the accident, said passenger jeepney was driven by Corado Roque.

The contract between Conrado Roque and defendant Delfin Bernardo was that Roque was to pay to defendant the

sum of P8.00, which he paid to said defendant, for privilege of driving the jeepney, it being their agreement that

whatever earnings Roque could make out of the use of the jeepney in transporting passengers from one point to

another would belong entirely to Conrado Roque.

As a result of the accident, Conrado Roque was prosecuted for homicide thru reckless imprudence before

the CFI of Manila, and that upon arraignment, Conrado Roque pleaded guilty to the information and was sentenced

to a jail term, to indemnify the heirs of the deceased in the sum of P3, 000.00 with subsidiary imprisonment in case of

insolvency. Conrado Roque served his sentence but he was not able to pay the indemnity because he was insolvent.

Issue: Whether or not an employer-employee relationship exists between a jeepney- owner and a driver under a

boundary system agreement.

Held: Yes, there exist an employer-employee relationship under a boundary system arrangement. The features

which characterize the boundary system- namely, the fact that the driver does not receive a fixed wage but gets only

the excess of the amount of fares collected by him over the amount he pays to the jeep- owner, and that the gasoline

consumed by the jeepney is for the account of the driver- are not sufficient to withdraw the relationship between them

from that of employer- employee. Consequently, the jeepney- owner is subsidiarily liable as employer in accordance

with article 103 of the Revised Penal Code.

The Court ruled that the judgment appealed from is hereby affirmed.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Tax Rates Effective January 1, 1998 Up To PresentDocument8 pagesTax Rates Effective January 1, 1998 Up To PresentJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Symbols For Signalling Circuit DiagramsDocument27 pagesSymbols For Signalling Circuit DiagramsrobievNo ratings yet

- The Study of 220 KV Power Substation Equipment DetailsDocument90 pagesThe Study of 220 KV Power Substation Equipment DetailsAman GauravNo ratings yet

- Celiac DiseaseDocument14 pagesCeliac Diseaseapi-355698448100% (1)

- High Risk Medications in AyurvedaDocument3 pagesHigh Risk Medications in AyurvedaRaviraj Pishe100% (1)

- PERSONS Complete DigestsDocument233 pagesPERSONS Complete DigestsJamie Del CastilloNo ratings yet

- Chapter VIII Ordinary Asset and Capital AssetsDocument3 pagesChapter VIII Ordinary Asset and Capital AssetsJasmin Alapag100% (2)

- Chapter VIII Ordinary Asset and Capital AssetsDocument3 pagesChapter VIII Ordinary Asset and Capital AssetsJasmin Alapag100% (2)

- Transpo Day 2 CasesDocument7 pagesTranspo Day 2 CasesJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Transpo Day 2 CasesDocument7 pagesTranspo Day 2 CasesJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Transpo Day 1 CasesDocument10 pagesTranspo Day 1 CasesJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Mabeza vs. NLRC labor case rulingDocument12 pagesMabeza vs. NLRC labor case rulingJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Chapter VIII Ordinary Asset and Capital AssetsDocument3 pagesChapter VIII Ordinary Asset and Capital AssetsJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Chapter VII Taxable Bases and RatesDocument5 pagesChapter VII Taxable Bases and RatesJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Chapter IX Accounting Method, Periods and Filing of ITRDocument4 pagesChapter IX Accounting Method, Periods and Filing of ITRJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- NIRC Sections Related To Gross IncomeDocument11 pagesNIRC Sections Related To Gross IncomeJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Chapter VIII Ordinary Asset and Capital AssetsDocument3 pagesChapter VIII Ordinary Asset and Capital AssetsJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Chapter IX Accounting Method, Periods and Filing of ITRDocument4 pagesChapter IX Accounting Method, Periods and Filing of ITRJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Chapter V1 Cost and Deductions PART IDocument8 pagesChapter V1 Cost and Deductions PART IJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Chapter V1 Cost and Deductions PART IDocument7 pagesChapter V1 Cost and Deductions PART IJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Chapter V1 Cost and Deductions PART IDocument7 pagesChapter V1 Cost and Deductions PART IJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Cover SheetDocument1 pageCover SheetJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Chapter IX Accounting Method, Periods and Filing of ITRDocument4 pagesChapter IX Accounting Method, Periods and Filing of ITRJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- A. What Is A "Common Carrier"?Document26 pagesA. What Is A "Common Carrier"?Jasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Chapter IV Gross Income NotesDocument5 pagesChapter IV Gross Income NotesJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Chapter IX Accounting Method, Periods and Filing of ITRDocument4 pagesChapter IX Accounting Method, Periods and Filing of ITRJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- HK Tour PackageDocument1 pageHK Tour PackageJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Getz 1Document1 pageGetz 1Jasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Tax Chapter 7Document5 pagesTax Chapter 7Jasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

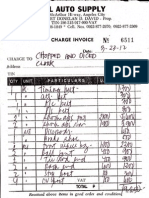

- Chopped and Diced Hot Rod Shop, Inc. Clark Freeport ZoneDocument6 pagesChopped and Diced Hot Rod Shop, Inc. Clark Freeport ZoneJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Legal Brief For Assignment 2.docx Rev3Document5 pagesLegal Brief For Assignment 2.docx Rev3Jasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Desiderata: by Max EhrmannDocument6 pagesDesiderata: by Max EhrmannTanay AshwathNo ratings yet

- Orientation Report PDFDocument13 pagesOrientation Report PDFRiaz RasoolNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument340 pagesUntitledFelipe Batista RetkeNo ratings yet

- Sony HCD-GTX999 PDFDocument86 pagesSony HCD-GTX999 PDFMarcosAlves100% (1)

- 1999 - Seismic Soil Structure Interaction in Buildings - I Analytical Aspects PDFDocument13 pages1999 - Seismic Soil Structure Interaction in Buildings - I Analytical Aspects PDFCesar PugsioNo ratings yet

- Ampersand MenuDocument5 pagesAmpersand MenuJozefNo ratings yet

- Spin - 2021Document60 pagesSpin - 2021Tanel LaanemägiNo ratings yet

- Thank You For Taking The Week 3: Assignment 3. Week 3: Assignment 3Document3 pagesThank You For Taking The Week 3: Assignment 3. Week 3: Assignment 3DhivyaNo ratings yet

- Mahle KFWA MAIN Data SheetDocument4 pagesMahle KFWA MAIN Data SheetRudnikNo ratings yet

- 2290 PDFDocument222 pages2290 PDFmittupatel190785No ratings yet

- L C R Circuit Series and Parallel1Document6 pagesL C R Circuit Series and Parallel1krishcvrNo ratings yet

- 2 - Alaska - WorksheetsDocument7 pages2 - Alaska - WorksheetsTamni MajmuniNo ratings yet

- OE Spec MTU16V4000DS2250 3B FC 50Hz 1 18Document6 pagesOE Spec MTU16V4000DS2250 3B FC 50Hz 1 18Rizki Heru HermawanNo ratings yet

- Schroedindiger Eqn and Applications3Document4 pagesSchroedindiger Eqn and Applications3kanchankonwarNo ratings yet

- True/False/Not Given Exercise 5: It Rains On The SunDocument2 pagesTrue/False/Not Given Exercise 5: It Rains On The Sunyuvrajsinh jadejaNo ratings yet

- Diagram "From-To" Pada Optimasi Tata Letak Berorientasi Proses (Process Layout)Document17 pagesDiagram "From-To" Pada Optimasi Tata Letak Berorientasi Proses (Process Layout)Febrian Satrio WicaksonoNo ratings yet

- NASA Technical Mem Randum: E-Flutter N78Document17 pagesNASA Technical Mem Randum: E-Flutter N78gfsdg dfgNo ratings yet

- Fatigue Life Prediction of A320-200 Aileron Lever Structure of A Transport AircraftDocument4 pagesFatigue Life Prediction of A320-200 Aileron Lever Structure of A Transport AircraftMohamed IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Personality Types and Character TraitsDocument5 pagesPersonality Types and Character TraitspensleepeNo ratings yet

- Abb 60 PVS-TLDocument4 pagesAbb 60 PVS-TLNelson Jesus Calva HernandezNo ratings yet

- Forecasting ExercisesDocument2 pagesForecasting ExercisesAsh VinaNo ratings yet

- PC Poles: DescriptionDocument2 pagesPC Poles: DescriptionSantoso SantNo ratings yet

- Kuffner Final PresentationDocument16 pagesKuffner Final PresentationSamaa GamalNo ratings yet

- Module 37 Nur 145Document38 pagesModule 37 Nur 145Marga WreatheNo ratings yet

- Absence Makes The Heart Grow FonderDocument27 pagesAbsence Makes The Heart Grow FondereljhunNo ratings yet

- MPC-006 DDocument14 pagesMPC-006 DRIYA SINGHNo ratings yet