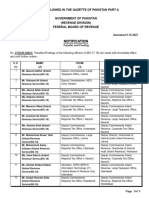

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The State of Domestic Commerce in Pakistan Study 6 - Wholesale Markets

Uploaded by

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The State of Domestic Commerce in Pakistan Study 6 - Wholesale Markets

Uploaded by

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdCopyright:

Available Formats

THE STATE OF DOMESTIC COMMERCE IN

PAKISTAN

STUDY 6

WHOLESALE MARKETS

For

The Ministry of Commerce

Government of Pakistan

November 2007

By

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) Ltd.

House No. 2, Street 44, F-8/1, Islamabad

Table of Contents

List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................................... i

Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................ iv

Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 3

Section 1: Introduction .................................................................................................. 5

1.1. Structure of the Wholesale Market for Fruits and Vegetables .................................... 5

1.2. Barriers to the Development of Wholesale Markets ................................................... 6

1.3. A Model for Wholesale Markets ................................................................................. 6

Section 2: Survey Findings for Wholesale ................................................................... 8

2.1 Establishment of the Business and Owner Characteristics ........................................ 8

2.2 Output and Value Addition Indices ........................................................................... 11

2.3 Market Competition ................................................................................................. 12

2.4 Constraints .............................................................................................................. 14

2.5 Financing ................................................................................................................. 15

2.5.1 Financing for Business Establishment .......................................................... 15

2.5.2 Loan Applications......................................................................................... 17

2.5.3 Loan Applications......................................................................................... 17

2.6 Linkages .................................................................................................................. 18

2.7 Employment ............................................................................................................ 19

2.8 Governance Issues.................................................................................................. 20

2.9 Issues of Expansion ................................................................................................ 21

2.10 Facilities for Wholesale Enterprises ......................................................................... 22

Section 3: Conclusions ............................................................................................... 23

3.1 Policy Recommendations ........................................................................................ 23

List of Tables

Table 1.1: Marketing Margins for Various Vegetables (percent of Consumer Price) ....... 6

Table 2.1: Summary Statistics of Firm Age ..................................................................... 8

Table 2.2: Relative Frequency Distribution of Groups of Firm Age .................................. 8

Table 2.3: Relative Frequency Distribution of Acquisition of Business ............................ 9

Table 2.4: Ownership Type ........................................................................................... 10

Table 2.5: Summary Statistics of Average Monthly Revenue ........................................ 11

Table 2.6: Average Monthly Revenue ........................................................................... 12

Table 2.7: Similar Enterprises Within a Radius of 1 km ................................................. 12

Table 2.8: Greatest Barrier to Market Entry .................................................................. 13

Table 2.9: Most Important Constraint to Growth ............................................................ 14

Table 2.10: Breakdown of Sources of Startup Capital ..................................................... 16

Table 2.11: Breakdown of Sources of Startup Capital by Province ................................. 17

Table 2.12: Percent of Goods Purchased on Credit ........................................................ 18

Table 2.13: Patterns of Full Time Employment ............................................................... 19

Table 2.14: Registration Requirements ........................................................................... 20

Table 2.15: Governance Issues ...................................................................................... 21

Table 2.16: Have you considered expanding your business to other regions? ................ 21

List of Figures

Figure 1: Relative Frequency Distribution of Firm Age .................................................. 9

Figure 2: Relative Frequency Distribution of Acquisition of Business .......................... 10

Figure 3: Relative Frequency Distribution of Ownership Type ..................................... 11

Figure 4: Relative Frequency Distribution of Similar Enterprises

Within a Radius of 1 Km ............................................................................... 13

Figure 5: Relative Frequency Distribution of Rankings of Entry Barriers ..................... 14

Figure 6: Most Important Constraints to Growth .......................................................... 15

Figure 7: Summary Statistics of Sources of Startup Capital ........................................ 16

Figure 8: Relative Frequency Distribution of Number of Full-time Paid Employees ..... 20

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) i

List of Abbreviations

ABAD Association of Builders and Developers

ADB Asian Development Bank

ADBI Asian Development Bank Institute

APCA All Pakistan Contractors Association

ATT Afghan Trade Transit

BAF Bank AlFalah

BCI Business Competitiveness Index

BOR Board of Revenue

CAA Civil Aviation Authority

CBM Cubic meter

CBR Central Board of Revenue

CDA Capital Development Authority

CIB Credit information bureau

CMR Contract for the International Carriage of Goods by Road

CPI Corruption Perceptions Index

CPIA Country Policy and Institutional Assessment

DFID Department for International Development

DHA Defense Housing authority

EDF Export Development Fund

EIU Economist Intelligence Unit

EOS Executive Opinion Survey

EPB Export Promotion Bureau

ESCAP Economic and Social Development in Asia and the Pacific

FBS Federal Bureau of Statistics

FCL Full Container Load

FDI Foreign Direct Investment

FIAS Foreign Investment Advisory Service

Ft Foot

FY Fiscal Year

GCI Global Competitiveness Index

GCR Global Competitiveness Report

GD Goods Declaration

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GoP Government of Pakistan

GOR Government Officials Residences

GRT Gross Register Tonnage

GST General Sales Tax

HBFC Housing Building Finance Corporation

HBL Habib Bank Limited

HDR Human Development Report

HFIs Housing Finance Institutions

IFC International Finance Corporation

IFS International Financial Statistics

IMF International Monetary Fund

ISAL Informal Subdivision of Agricultural Land

ISO International Standards Organization

IT Information Technology

ITU International Telecommunications Union

Survey Report on Domestic Commerce

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) ii

KBCA Karachi Building Control Authority

KDA Karachi Development Authority

KESC Karachi Electric Supply Corporation

KM(s) Kilometer(s)

KPT Karachi Port Trust

KSE Karachi Stock Exchange

LCL Less Than Container Load

LOA Length Overall

MCB Muslim Commercial Bank

MENA Middle East and North Africa

MOC Ministry of Commerce

MOD Ministry of Defense

MTDF Medium Term Development Framework

NBP National Bank of Pakistan

NCS National Conservation Strategy

NER Net Primary School Enrollment Rate

NHA National Highway Authority

NIE Newly industrialized economy

NIT National Institute of Transport

NLC National Logistics Cell

NTN National Tax Number

NTRC National Transportation Research Center

NTTFC National Trade and Transport Facilitation Committee

NWFP North West Frontier Province

PASSCO Pakistan Agricultural Storage and Services Corporation

PEC Pakistan Engineering Council

PHDEB Pakistan Horticulture Development and Export Board

PIAC Pakistan International Airlines Corporation

PIDE Pakistan Institute Of Development Economists

PIHS Pakistan Integrated Household Survey

PKR Pakistani Rupee

PQA Port Qasim Authority

PR Pakistan Railways

PREF Pakistan Real Estate Federation

PSDP Public Sector Development Program

R&D Research and Development

REER Real Effective Exchange Rate

REITs Real Estate Investment Trusts

RICS Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors

SAI Social Accountability International

SBP State Bank of Pakistan

SKAA Sindh Katchi Abadis Authority

SME Small and Medium Enterprises

SPS Sanitary and Phytosanitary

SRO Statutory Regulation Order

Std Standard

TEP Total Factor Productivity

TEU Twenty-Foot Equivalent Units

TI Transparency International

TOR Terms of Reference

Survey Report on Domestic Commerce

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) iii

TSDI Transport Sector Development Initiative

TTFP Trade and Transportation Facilitation Program

UK United Kingdom

UNDP United Nations Development Program

US United States

USA United States of America

USC Utility Stores Corporation

USD United States Dollars

WAPDA Water and Power Development Authority

WDI World Development Indicators

WEF World Economic Forum

WGI Worldwide Governance Indicators

WTO World Trade Organization

Survey Report on Domestic Commerce

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) iv

Acknowledgment

The IDS team owes a debt of gratitude to the officers of the Ministry of Commerce for their

guidance, assistance and feedback during the course of this study. Our special thanks go out,

in particular, to Syed Asif Ali Shah, Secretary; Mr. Naseem Qureshi and Mr. Ashraf Khan,

Additional Secretaries; Mr. Abrar Hussian, Joint Secretary; Syed Irtiqa Zaidi, Consultant and

Mr. Qaseem Subhani, Section Officer, for sparing their precious time and efforts for the

study.

We feel a deep sense of gratitude for the Minister for Commerce. Mr. Humayun Akhtar

Khan, who took out considerable time from his busy schedule to guide us. It was his sincere

and deep conviction which enabled us to conduct and compile this detailed and

comprehensive study on Domestic Commerce of our country. His apt guidance and keen

analytical oversight were extremely helpful in finalizing the study and formulating the policy

recommendations.

This study has benefited from comments received from the following:

1. State Bank of Pakistan, Karachi.

2. Federal Board of Revenue, Government of Pakistan, Islamabad.

3. Planning and Development Division, Government of Pakistan, Islamabad.

4. Trade Development Authority, Government of Pakistan, Karachi.

5. (Management Consultants) Establishment Division, Government of Pakistan,

Islamabad.

6. Finance Division, Government of Pakistan, Islamabad.

7. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad.

8. NTTFC, Karachi.

9. FPCCI, Karachi.

10. Planning and Development Board, Government of Punjab, Lahore.

11. Planning and Development Board, Government of NWFP, Peshawar.

12. Planning and Development Board, Government of Sindh, Karachi.

13. Planning and Development Board, Government of Balochistan, Quetta.

14. Investment and Commerce Department, Government of Punjab, Lahore.

15. SMEDA, Lahore.

16. Statistics Division, Government of Pakistan, Islamabad.

1

WHOLESALE MARKETS*

by

SAFIYA AFTAB

DR. GEORGE BATTESE

DR. SOHAIL J. MALIK

* For detailed survey results, please see separate volume entitled Basic Statistics of the Sample

Survey Data.

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 3

Executive Summary

1. In Pakistan, the only clearly defined wholesale markets that exist are for agricultural

produce, particularly fruit and vegetables. Literature on other sorts of markets is scarce. The

local Mandi (Market) for fruits and vegetables acts as the central link between producers and

consumers. Mandi owners can be characterized as commission agents who charge a fixed

sum from the growers for usage of their facility and services. Wholesalers buy in lots through

an auction conducted under the supervision of the Mandi owner or his designated lieutenant

(sometimes called a Munshi). Having auctioned the goods, the Mandi owner (Ardi/Arti) pays

off the growers after deducting his commission. The wholesaler (Beopaari/Tajir) then sells to

individual retailers ranging from fruit and vegetable vendors (Rehriwaala) to shopkeepers in

retail markets. In bigger cities like Karachi and across the Punjab province, wholesale

markets for fruits and vegetables are controlled by the Agricultural Department through

market committees set up at the district level.

2. In Pakistan, there is very little planning involved in the development of fruit and

vegetable wholesale markets, which are often congested, lack well designed entry and exit

points, and are devoid of basic infrastructure facilities like roads, storage, etc. Limited

provisions exist to minimize wastage of fruits and vegetables caused by poor farm to market

roads; lack of refrigerated transport and warehousing; use of low-quality packaging materials

and faulty methods of loading and unloading.

3. A total of 500 wholesale establishments were included in the sample survey, almost a

fifth of which traded in groceries, while the rest covered a range of establishments including

medical supplies, clothing, books etc. The key findings of the survey are as follows. As is the

case with retail trade, the wholesale market is heavily tilted towards proprietorships, and

almost 90 percent of survey respondents were sole owners of their businesses. The median

monthly revenue of wholesale establishment was estimated at Rs. 300,000. About 66 percent

of firms interviewed reported that they had faced barriers to entry, and 76 percent cited the

need for finance as the most significant barrier. Access to finance came across as the most

important constraint to growth for wholesale enterprises, with 47.8 percent of respondents

citing this as the most important factor restricting expansion. The governments regulation

structure (taxation, systems of licensing etc) were cited as primary constraints in 20.8 percent

of cases, while the quality of public services was cited by almost 18.3 percent of respondents

as the most important constraint.

4. As in the case of retail establishments, wholesalers had, on an average, financed

approximately 83 percent of the costs of establishing the business through own or family

savings. In spite of the fact that access to finance was repeatedly mentioned as an obstacle to

growth, and an impediment when it came to starting a business, an overwhelming 94 percent

of respondents said that they had not considered applying for a loan in the last five years.

When asked to rank reasons why they had considered applying for loans, almost 41 percent

of respondents said they did not need funds, while a similar proportion (42.5 percent)

expressed reservations about contracting loans for religious reasons, or the belief that interest

bearing transactions are prohibited.

5. The wholesale sector does seem to generate a significant amount of employment, with

almost 41 of respondents saying that they employ two or three people full time. Disputes over

late payments appear to be a common occurrence in wholesale trade, in spite of the

understanding of the prevalence of credit based transactions, with over half of respondents

saying that they had been involved in such a dispute in the last year.

6. The wholesale sector is characterized by small proprietors In a wholesale sector where

kinship networks are important for doing business and dispute resolution is almost entirely

informal, the lack of movement towards building business conglomerates and taking

Survey Report on Domestic Commerce

Innovative Devel 4

advantage of economies of scale is very much an expected outcome. Individual business

volumes cannot increase significantly in an environment where business dealings are rarely

rooted in legal agreements.

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 5

Section 1

Introduction

1. The distinction between wholesale and retail markets is sometimes blurred,

particularly for manufactured goods, which do not really go through a reselling process. In

Pakistan, the only clearly defined wholesale markets that exist are for agricultural produce,

particularly fruit and vegetables. Literature on other sorts of markets is scarce, and it is

expected that more information on the nature of wholesale or reselling activities will be

forthcoming from the proposed domestic commerce survey.

1.1. Structure of the Wholesale Market for Fruits and Vegetables

2. The local Mandi (Market) for fruits and vegetables acts as the central link between

producers and consumers. Despite variance in the size of such markets, there exists a

relatively standardized model of transactions with precisely defined roles for key players in

the supply chain and a largely uniform set of rules.

3. In Pakistan, most fruit and vegetable markets are privately owned in the smaller towns

and many cities, particularly in NWFP. Mandi owners can be characterized as commission

agents who charge a fixed sum from the growers for usage of their facility and services.

Wholesalers buy in lots through an auction conducted under the supervision of the Mandi

owner or his designated lieutenant (sometimes called a Munshi). Having auctioned the

goods, the Mandi owner (Ardi/Arti) pays off the growers after deducting his commission. The

wholesaler (Beopaari/Tajir) then sells to individual retailers ranging from fruit and vegetable

vendors (Rehriwaala) to shopkeepers in retail markets.

4. In bigger cities like Karachi and across the Punjab province, wholesale markets for

fruits and vegetables are controlled by the Agricultural Department through market

committees set up at the district level. However, the same system of commission agents and

wholesalers exist as in the former case.

5. The transaction channel between the Ardi and the Beopaari is of central importance.

Whereas the former is assured of a definite profit, the latters profit margin is conditioned by

a higher risk factor inevitably associated with the relative inefficiency emanating from a

greater number of smaller transactions closer to the tail end of the supply chain.

6. Greater risk, however, also means greater payback in terms of high profit margins.

Chaudury and Bashir (2000) showed that wholesalers make more profits than commission

agents in case of vegetables (Table 1.1).

1

The evidence also reflects the conventional logic

1 The Table is reproduced from Muhammad G. Chaudury and Bashir Ahmad, Pakistan in Mubarik Ali (ed.)

Dynamics of Vegetable Production, Distribution and Consumption in Asia, The World Vegetable Center

(AVRDC), 2000, pp. 271-302. Available at http://www.avrdc.org/pdf/dynamics/Pakistan.pdf . The studies

cited at the bottom of the table refer to 1) K. Lodhi, Food Marketing Margins, The Pakistan Economic

Analysis Network Project and the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Cooperative, Islamabad, 1990; 2) United

Consultants Group Ltd. Agricultural Marketing in Pakistan, prepared for GoP, Lahore, 1984; 3) A.A Kokab

Survey Report on Domestic Commerce

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 6

of a higher per-unit profit margin of selling at the retail end of the supply chain as against

selling at the intermediate wholesale level. This, nevertheless, naturally goes hand in glove

with the even greater risk faced by retailers of fresh fruit and vegetables owing to the short

shelf life of such items.

Table 1.1: Marketing Margins for Various Vegetables (percent of Consumer Price)

Potato Onion Tomato Peas Carrot Brinjal

Lodhi

1

UCL

2

Kokab&

Smith

3

Kokab

4

Lodhi UCL Siddique

5

Lodhi UCL UCL

A B

Grower 56.0 62.1 63.7 49.1 55.0 57.0 55.5 54.9 25.0 56.9 60.6

Commission Agent - 8.5 11.3 1.5 1.7 7.8 3.4 - 9.0 6.9

Wholesaler(Pharia) - 11.5 2.1 21.0 14.8 - 10.0 16.4 - 12.8 12.4

Retailer - 17.9 22.9 23.4 28.5 - 26.7 25.3 - 21.3 20.1

Marketing margin 44.0 37.9 36.3 50.9 45.0 43.0 44.5 45.1 75.0 43.1 39.4

Marketing margin 44.0 37.9 36.3 50.9 45.0 43.0 44.5 45.1 75.0 43.1 39.4

Note: winter onion; b. Stored winter onion; - implies that details are not available.

1.2. Barriers to the Development of Wholesale Markets

7. In Pakistan, there is very little planning involved in the development of fruit and

vegetable wholesale markets, which are often congested, lack well designed entry and exit

points, and are devoid of basic infrastructure facilities like roads, storage, etc. In Lahore, for

instance, only one (Ravi Link Road Fruit and Vegetable Market in Badami Bagh) out of the

four fruit and vegetable markets that were developed more than two decades ago is fully

functional. That too, however, is facing numerous problems including congestion due to high

traffic as well as poor parking, berthing, storage and drainage facilities.

2

Such problems

typify most Mandis in Pakistans major urban centers and towns.

8. One obvious reason for overcrowding is the increase in demand for foodstuffs

following a growth in urban population due to relatively high birth rates and even higher rates

of rural-urban migration. In some cases, city administrations have sought to deal with the

problem by proposing to shift the Mandis out of cities. Such attempts, however, are bound to

be problematic largely because they inevitably increase the cost of redistribution within the

city.

3

Limited provisions exist to minimize wastage of fruits and vegetables caused by poor

farm to market roads; lack of refrigerated transport and warehousing; use of low-quality

packaging materials and faulty methods of loading and unloading.

4

1.3. A Model for Wholesale Markets

9. In Pakistan, as in most of the developing world, where farm structures and ownership

remain fragmented and where cooperatives and farmer groupings are largely underdeveloped,

wholesale markets provide an easy inlet into the market for the great majority of small

farmers. In turn, an efficient Mandi structure is crucial to the proper functioning of local

and A.E. Smith, Marketing of Potatoes in Pakistan, Pakistan Agricultural Resource Council, 1989; 4) A.A

Kokab, Improving Marketing of Potatoes in District Okara, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad,

Unpublished M. Sc. Thesis, 1984; 5) M. Siddique, An Investigation into the Farmers Marketing Problems of

Major Vegetables in Faisalabad Vegetable Market, University Of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Unpublished M.

Sc. Thesis, 1980.

2 See Edward Seidler, Wholesale Market Development FAOs Experience, Paper prepared for the 22nd

Congress of the World Union of Wholesale Markets, Durban, September 2001. Available at

http://www.fao.org/ag/magazine/markets.pdf.

3 See Urban Food Security and Food Marketing in Metropolitan Lahore, Pakistan, Ministry of Food,

Agriculture and Livestock, Report of a Workshop at Town Hall, Lahore, 10th June 1999. Available at

http://www.fao.org/AG/ags/AGSM/SADA/DOCS/PDF/AC2199E.PDF

4 See Pakistan: Improving the Performance of the Housing, Tourism and Retail Sectors, Foreign Investment

Advisory Service - The World Bank, Washington, August 2005, p.29

Wholesale Markets

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 7

economies. The development of such wholesale markets in Pakistan demands a holistic

approach subsuming a whole set of interlinked sectors such as transport, rural infrastructure,

storage, etc.

10. As a starting point, wholesale market development has to be a participatory process

involving inputs from all stakeholders including farmers, transporters, retailers, traders, and

wholesalers. Left to Mandi owners and/or the public sector alone, market development will

fall prey to vested interests and bureaucratic sloth.

11. Wholesale market ownership has also been a much debated issue. In Africa,

wholesale markets are public facilities, owned and managed by municipalities.

5

However,

there is a tendency on the part of the latter to reinvest very little on market maintenance and

development. In Pakistan, whether privately owned or under the administrative control of

Market Committees, there has traditionally been very little by way of reinvestment into

market infrastructure and operations. Moreover, Market Committees are also not sufficient

enough to bring about a meaningful infrastructural improvement. For instance, a total of Rs.

260 million was generated against Rs. 200 million salary and operating cost in the Punjab

province in 2003.

6

12. Besides the lack of adequate finances, corruption is another major bottleneck. The

only Fruit and Vegetable Mandi in Karachi, for instance, is losing out on both counts. Not

only does it have to contend with frequent disruptions in water and electricity supplies due to

nonpayment of dues, many officials in the Market Committee have been consistently accused

of ignoring illegal encroachments.

7

13. Ideally, markets of such nature should be administered as a public good through a

partnership between the public and private sectors where the former has to ensure supply of

utilities and provision of basic road infrastructure. The Market Committees have to involve

the associations of traders and wholesalers into the decision making process. The building of

trust between the two is an essential ingredient for better management as well as for better

regulation of safety and hygiene standards in the market.

5 Edward Seidler, Ibid.

6 Pakistan: Punjab Economic Report, Government of Punjab, March 31, 2005, p.51

7 See, for instance, Sabzi Mandi Rapidly Degenerating Due to Encroachments, The News, February 16,

2005. See also, Sabzi Mandi Traders Seek Action against Market Committee, The News, May 20, 2004.

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 8

Section 2

Survey Findings for Wholesale

14. A total of 500 wholesale establishments were included in the sample survey, almost a

fifth of which traded in groceries, while the rest covered a range of establishments including

medical supplies, clothing, books etc. The key findings of the domestic commerce survey,

with respect to wholesale establishments are as follows.

2.1 Establishment of the Business and Owner Characteristics

15. The bulk of wholesale enterprises visited (almost 23.8 percent) had started operations

within the last four years, with a further 20 percent having started operations within the last

five to nine years, and 17.6 percent in the last 10 to 14 years. This trend was particularly

marked in Balochistan, where almost 38 percent of establishments visited had come into

being in the last 4 years. The median age of establishments was about 11 years. Thus, as in

the case of retail outlets, most wholesale enterprises were relatively new, indicating a high

rate of turnover.

Table 2.1: Summary Statistics of Firm Age

Province Mean Std. Error of Mean Median Minimum Maximum

Punjab 13.47 .044 10.50 0 58

NWFP 12.09 .087 10.00 0 46

Sindh 16.94 .110 11.00 0 76

Balochistan 9.58 .239 7.00 0 46

Pakistan 13.83 .038 11.00 0 76

Table 2.2: Relative Frequency Distribution of Groups of Firm Age

Frequency Percent Valid Percent Cumulative Percent

Valid 0 thru 4 119 23.8 23.8 23.8

5 thru 9 100 20.0 20.0 43.8

10 thru 14 88 17.6 17.6 61.4

15 thru 19 63 12.6 12.6 74.0

20 thru 24 37 7.4 7.4 81.4

25 thru 29 32 6.4 6.4 87.8

30 thru 34 18 3.6 3.6 91.4

35 thru 39 21 4.2 4.2 95.6

40 thru 44 3 .6 .6 96.2

45 thru 49 6 1.2 1.2 97.4

50 thru 59 10 2.0 2.0 99.4

60 thru 76 3 .6 .6 100.0

Total 500 100.0 100.0

Wholesale Markets

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 9

Figure 1: Relative Frequency Distribution of Firm Age

0 thru 4 5 thru 9 10 thru

14

15 thru

19

20 thru

24

25 thru

29

30 thru

34

35 thru

39

40 thru

44

45 thru

49

50 thru

59

60 thru

76

Firm Age

0

5

10

15

20

25

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

16. Almost three quarters of all respondents had established their businesses themselves,

while about 16.2 percent had inherited the business. Only 8.4 percent of respondents had

acquired the establishment as a running business. These trends were roughly the same

across provinces, but Balochistan stood out as the province where almost 85 of wholesale

businesses had been established from scratch.

Table 2.3: Relative Frequency Distribution of Acquisition of Business

Frequency Percent Valid Percent Cumulative Percent

Valid Established 372 74.4 74.4 74.4

Bought as running business 42 8.4 8.4 82.8

Inherited 81 16.2 16.2 99.0

Other 5 1.0 1.0 100.0

Total 500 100.0 100.0

Survey Report on Domestic Commerce

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 10

Figure 2: Relative Frequency Distribution of Acquisition of Business

Established Bought as running

business

Inherited Other

Methods of acquisition

0

20

40

60

80

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

17. As is the case with retail trade, the wholesale market is heavily tilted towards

proprietorships, and almost 90 percent of survey respondents were sole owners of their

businesses. There were some variations within provinces Punjab had the highest proportion

of partnerships at almost 13 percent, with 87 percent sole proprietorships. Thus the sector is

characterized by the predominance of small, single owner enterprises.

Table 2.4: Ownership Type

Frequency Percent Valid Percent Cumulative Percent

Valid Proprietorship 449 89.8 89.8 89.8

Partnership 51 10.2 10.2 100.0

Total 500 100.0 100.0

Wholesale Markets

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 11

Figure 3: Relative Frequency Distribution of Ownership Type

Proprietorship Partnership

Ownership type

0

20

40

60

80

100

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

2.2 Output and Value Addition Indices

18. As expected, there was significant variation in the reported revenues of the

establishments in this category. The median monthly revenue was estimated at Rs. 300,000

while the mean was estimated at Rs. 899807 per month, but the maximum reported was Rs.

35 million. About 65 percent of establishments had average monthly revenues of up to Rs.

550,000. In general, average monthly revenues for wholesale were thus significantly higher

than for retail establishments. Table 2.5 gives the breakdown of average monthly revenue for

wholesale establishments.

Table 2.5: Summary Statistics of Average Monthly Revenue

Province Revenue

Punjab Mean 1030135.02

Std. Error of Mean 10329.405

Median 450000.00

Std. Deviation 2696322.246

Minimum 5000

Maximum 35000000

NWFP Mean 419353.33

Std. Error of Mean 3645.286

Median 200000.00

Std. Deviation 481955.849

Minimum 15000

Maximum 2223200

Sindh Mean 824027.40

Std. Error of Mean 13629.785

Median 205000.00

Std. Deviation 1890487.113

Minimum 6000

Maximum 15000000

Continued

Survey Report on Domestic Commerce

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 12

Province Revenue

Balochistan 1604

Mean 1508461.54

Std. Error of Mean 69180.445

Median 300000.00

Std. Deviation 2770398.283

Minimum 25000

Maximum 12000000

Pakistan Mean 899807.46

Std. Error of Mean 7192.859

Median 300000.00

Std. Deviation 2346912.572

Minimum 5000

Maximum 35000000

Table 2.6: Average Monthly Revenue

Classes Frequency Valid Percent Cumulative Percent

Up to 100,000 111 20.5 20.5

100,000 to 250,000 117 21.6 42.1

250,000 to 400,000 72 13.3 55.5

400,000 to 550,000 50 9.2 64.7

550,000 to 700,000 34 6.3 71

Over 700,000 157 29.0 100

Total 541 100

19. The data on profits is again evident of a skewed distribution with mean profit

recorded at just over Rs. 80,000 while median profit was Rs. 35,000. As in the case of retail

enterprises, calculated profit was also estimated, and median calculated profit came to just

above Rs. 16,000 per month indicating a tendency to understate revenues or overstate

expenditure when a breakdown is sought.

20. Over half (56.6 percent) of wholesale traders rented their premises, and the median

worth of their premises was Rs. 3 million. The mean value added for wholesalers came to

approximately Rs. 54,000, but once again the provincial disparity was apparent with value

added in Punjab averaging about Rs. 124,000.

2.3 Market Competition

21. Wholesale markets are generally clustered by nature of goods, so market competition was

not surprisingly fairly intense with a third of respondents saying that there were more than 25

similar outlets in the vicinity. Such clustering was particularly evident in NWFP, where 33.2

percent of respondents said that up to 25 similar enterprises could be found in a radius of one km.

Table 2.7: Similar Enterprises Within a Radius of 1 km

Frequency Percent Cumulative Percent

1 to 5 133 26.6 26.6

6 to 11 85 17.0 43.6

12 to 25 92 18.4 62.0

More than 25 166 33.2 95.2

Dont know 24 4.8 100.0

Total 500 100.0

Wholesale Markets

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 13

Figure 4: Relative Frequency Distribution of Similar Enterprises Within a Radius of 1 Km

1 to 5 6 to 11 12 to 25 more than 25 Do not know

Number of competing firms

0

10

20

30

40

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

22. About 66 percent of firms interviewed reported that they had faced barriers to entry,

and 76 percent cited the need for finance as the most significant barrier. The need to have

personal contacts in the proposed business was cited as the most important barrier by 7.6

percent of respondents, while almost a third of respondents cited it as the second key barrier

to entry. Government regulations and tariffs were cited as the second and third ranked

barriers by about 20 percent of respondents. These results were more or less consistent

across provinces with some minor variations, for example in Balochistan the proportion of

respondents citing lack of finance as the most important entry barrier was 65 percent, but a

range of other issues such as lack of market information and lack of demand were cited as

barriers also.

Table 2.8: Greatest Barrier to Market Entry

Frequency Percent Valid Percent Cumulative Percent

Valid Large amount of capital/finance needed 248 75.4 75.4 75.4

Government regulations/tariffs 12 3.6 3.6 79.0

Corruption in registration agencies 11 3.3 3.3 82.4

Mafia or cartel restricts entry 3 .9 .9 83.3

Must have personal contacts in industry 25 7.6 7.6 90.9

Others 30 9.1 9.1 100.0

Total 329 100.0 100.0

Survey Report on Domestic Commerce

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 14

Figure 5: Relative Frequency Distribution of Rankings of Entry Barriers

Large amount of

capital/finance

need

Government

regulations/tariffs

Corruption in

registration

agencies

Mafia or cartel

restricts entery

Must have

personel contacts

in industry

Others

Most difficult issue

0

20

40

60

80

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

2.4 Constraints

23. As in the case of retail enterprises, access to finance once again came across as the

most important constraint to growth for wholesale enterprises, but in case of such enterprises,

45.6 percent of respondents cited this as the most important factor restricting expansion. The

governments regulation structure (taxation, systems of licensing etc) were cited as primary

constraints in 19.3 percent of cases, while the quality of public services was cited by almost

18.9 percent of respondents as the most important constraint. Corruption and law and order

problems were cited as the third ranked constraints to growth by 27 percent and 19.5 percent

of respondents, but were rarely cited as primary constraints.

Table 2.9: Most Important Constraint to Growth

Frequency Percent Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid Taxation and regulation systems 95 19.0 19.3 19.3

Quality of public services (Electricity, roads,

etc)

93 18.6 18.9 38.1

Lack of access to finance 225 45.0 45.6 83.8

Lack of clear regulations for property

agreements

20 4.0 4.1 87.8

Corruption 19 3.8 3.9 91.7

Law and order situation 41 8.2 8.3 100.0

Total 493 98.6 100.0

Missing System 7 1.4

Total 500 100.0

Wholesale Markets

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 15

Figure 6: Most Important Constraints to Growth

Taxation and

regulation

system

Quality of

public

services

Lach of

access to

finance

Lack of clear

rgulation for

property

rights

Corruption Law and

order

situation

Most important constraint to growth

0

10

20

30

40

50

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

24. There was some interesting variation across provinces, particularly with regard to

Sindh, where the proportion of respondents who said that lack of finance was the most

important constraint was just under 40 percent, but the quality of public services was cited as

an issue by almost 19 percent of respondents and the law and order situation was cited as the

prime constraint by almost 18 percent. In Balochistan, the quality of public services ranked

equally with lack of access to finance as the prime constraint to growth of enterprises both

being cited by 28 percent of respondents as the most important constraint. Similarly, the law

and order situation and taxation issues also came out strongly as constraints in Balochistan,

both being cited as prime issues by 16 percent of respondents approximately. Thus in at least

two provinces of the country, recent socio-political scenarios have not been conducive to

business, and this negative trend is reflected in the responses of the business community.

2.5 Financing

2.5.1 Financing for Business Establishment

25. As in the case of retail establishments, wholesalers had, on an average, financed

approximately 84.8 percent of the costs of establishing the business through own or family

savings. Sale of assets had, on an average, financed 5.9 percent of the costs while loans from

family members had financed a further 5.24 percent.

Survey Report on Domestic Commerce

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 16

Table 2.10: Breakdown of Sources of Startup Capital

N Mean Std. Deviation

Statistic Statistic Std. Error Statistic

Own/Family savings 500 84.8 1.2 27.5

Remittances from abroad 500 2.01 .51 11.28

Sale of Assets 500 5.90 .80 17.85

Bank Loan 500 .96 .35 7.87

Loan from fam/friends 500 5.24 .69 15.49

Private money lenders 500 .17 .11 2.54

Others 500 .90 .33 7.48

Valid N (listwise) 500

Figure 7: Summary Statistics of Sources of Startup Capital

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Own/Family

savings

Remittances

from abroad

Sale of

Assets

Bank Loan Loan from

fam/friends

Private

money

lenders

Others

Wholesale Sources of startup capital

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

26. The tendency to use own savings was particularly strong in Sindh, where almost 95

percent of businesses had been established as such. Some other provincial anomalies also

stand out. In Punjab, the sale of assets accounted for about 9 percent of the costs of setting

up the business, where as in NWFP this source accounted for less than 1.5 percent. Bank

loans figured to any degree of prominence only in NWFP, where, on an average, 4 percent of

establishment costs were said to come from bank loans a somewhat unexpected result.

Loans from family and friends constituted almost 12 percent of establishment costs in

Balochistan, but only 2.5 percent in Sindh. Interestingly, the role of private money lenders

was practically non-existent in three of the provinces, but in Balochistan almost 2 percent of

establishment costs came from this source.

Wholesale Markets

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 17

Table 2.11: Breakdown of Sources of Startup Capital by Province

Province

Own/Family

savings

Remittances

from abroad

Sale of

Assets

Bank

Loan

Loan from

fam/friends

Private

money

lenders Others

Punjab Mean 80.20 2.94 9.04 .81 6.39 .13 .48

Std. Error

of Mean

.115 .050 .084 .021 .065 .006 .018

Std.

Deviation

30.326 13.206 21.998 5.651 17.198 1.634 4.650

NWFP Mean

84.82 3.75 1.43 3.57 3.75 .00 2.68

Std. Error

of Mean

.235 .129 .058 .145 .108 .000 .115

Std.

Deviation

30.000 16.536 7.423 18.558 13.831 .000 14.699

Sindh Mean

94.56 .00 2.36 .07 2.53 .00 .47

Std. Error

of Mean

.103 .000 .075 .006 .061 .000 .041

Std.

Deviation

14.343 .000 10.486 .819 8.453 .000 5.735

Balochistan Mean

77.31 .00 3.08 1.92 11.92 1.92 3.85

Std. Error

of Mean

.786 .000 .275 .240 .616 .240 .333

Std.

Deviation

31.457 .000 11.017 9.618 24.662 9.618 13.328

2.5.2 Loan Applications

27. In spite of the fact that access to finance was repeatedly mentioned as an obstacle to

growth, and an impediment when it came to starting a business, an overwhelming 94 percent

of respondents said that they had not considered applying for a loan in the last five years.

Sindh and Balochistan fell a little below the average on this count with 90 percent and 88

percent of respondents saying that they had never considered applying for a loan, while

Punjab and NWFP the proportion who had never considered the option was over 95 percent.

28. When asked to rank reasons why they had considered applying for loans, almost 41

percent of respondents said they did not need funds, while a similar proportion (42.5 percent)

expressed reservations about contracting loans for religious reasons, or the belief that interest

bearing transactions are prohibited. Interestingly, in NWFP where religious sentiments are

generally believed to dominate, only 36 percent of respondents cited the religious issue as the

most important one for not taking a loan. Almost 40 percent respondents in NWFP stated

that they simply did not need the loan, and 12 percent cited possible high interest as a

deterrent. The interest rate consideration tied with the religious consideration in NWFP

when respondents were asked to cite the second most important reason for not taking a loan,

but both these reasons being cited by 30 percent of respondents as the second major reason.

The relative convenience of getting financing from family or friends was also cited as the

prime reason for not applying for loans by 6.6 percent of respondents.

2.5.3 Loan Applications

29. Only 34 wholesalers interviewed reported having applied for a loan in the last three

years. Of those who had made such an application, 46.7 percent had approached a

commercial bank, and a similar 46.7 percent had approached a relative or friend. 46.7

percent of loans were applied for to invest in expansion of the existing business, while in

almost 27 percent of cases, the intent was to start up a new enterprise. The applications of 30

persons were approved, and these were divided almost equally between applications to

commercial banks and applications to friends and relatives. For the six cases where loan

Survey Report on Domestic Commerce

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 18

applications or requests were not approved, in 3 cases no explanation was given, while

insufficient collateral and bad credit history were also cited as reasons.

30. Average loan amounts sought by wholesalers were, predictably higher than those

applied for by retailers given the larger size of the average business. The average loan

amount requested was in the range of Rs. 467,000, while the amount actually received was

about Rs. 351,000. The median amount asked for was Rs. 300,000, while the minimum

amount asked for and the minimum received was Rs. 25,000.

31. Like retail trade, wholesale trade also depends heavily on the extension of credit,

wherein sales or purchases of goods are affected with payment delays being implicit in the

transaction, although no interest is charged. Almost 70 percent of wholesalers said that they

purchase goods on credit as a routine in business transactions. Almost 25 percent of

wholesalers claimed that up to 65 percent of their purchases were made on credit. Table 2.18

gives the complete breakdown.

Table 2.12: Percent of Goods Purchased on Credit

Percent of Goods

Purchased on

Credit

Frequency Valid Percent Cumulative Percent

1 through 10 16 4.8 4.8

11 through 20 29 8.7 13.5

21 through 30 45 13.5 27.0

31 through 40 43 12.9 39.9

41 through 50 84 25.2 65.2

51 through 60 24 7.2 72.4

61 through 70 18 5.4 77.8

71 through 80 28 8.4 86.2

81 through 90 7 2.1 88.3

91 through 100 39 11.7 100.0

Total 333 100.0

2.6 Linkages

32. The hypothesis for Pakistan was that wholesalers, even in urban centers, tend to

restrict the scale of their businesses to their environs, and rarely venture beyond their

hometowns. The data bears this out to some extent. On average wholesalers purchased 41

percent of their entire stock of merchandise from the same town, and on average sold 59

percent of their entire stock to retailers in the same city. This was most pronounced in Sindh,

where almost 61 percent of respondents procure their products from the same city, and a

further 20 percent from the same province. This effect seems to have become most

pronounced because of the significant representation of Karachi in the sample for Sindh,

Karachi being a largely self-contained market. NWFP and Balochistan were the least self

contained provinces with approximately 35 percent of wholesale goods traded coming from

other provinces.

33. With regard to the use of business related services, 88 percent of respondents had

never used engineering services, 94 percent had never used management consultants, 78.5

percent had never used marketing services, 92 percent had never used accounting services

and 95 percent had never used IT services, and 90 percent had never used legal services.

This points to the informal nature of transactions in the wholesale sector, and the small scale

of individual businesses.

Wholesale Markets

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 19

2.7 Employment

34. The hypothesis was that as the services sector grows, it is increasingly absorbing

both unskilled and semi-skilled labor. However, given the small size of the average business,

17.5 percent of respondents did not employ any full-time paid employees at their outlets. A

further 22 percent employed one person full time, while over a quarter of respondents

employed two people full time. Only 9.8 percent of enterprises employed 5 to 10 persons,

while less than 2 percent employed more than ten persons. NWFP had the lowest level of

employment generation in the wholesale sector, with a quarter of establishments not using

any full time paid labor, and a further one third employing only one person. On an average,

wholesale traders in Sindh and Punjab employed two persons at their premises. The data for

Balochistan showed an average of 5 persons employed per establishment, but the data may

have been biased by the small size of the sample.

35. About 91 percent of enterprises did not retain any part time employees (where part

time was defined as employees working less than five hours a day). Over 30 percent of

employees worked 10 to 12 hours a day. Of the total respondents, 43 percent said that none

of their employees had finished primary school.

36. The table below summarizes employment characteristics in the wholesale sector. The

sector does seem to generate more employment than retail, with almost 41 of respondents

saying that they employ two or three people full time. 91 percent of establishments had no

part time employees.

Table 2.13: Patterns of Full Time Employment

Frequency Percent Valid Percent Cumulative Percent

Valid .00 88 17.6 17.6 17.6

1.00 110 22.0 22.0 39.7

2.00 131 26.2 26.3 65.9

3.00 72 14.4 14.4 80.4

4.00 39 7.8 7.8 88.2

5.00 23 4.6 4.6 92.8

6.00 11 2.2 2.2 95.0

7 thru 10 15 3.0 3.0 98.0

11 thru 24 10 2.0 2.0 100.0

Total 499 99.8 100.0

Missing System 1 .2

Total 500 100.0

Survey Report on Domestic Commerce

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 20

Figure 8: Relative Frequency Distribution of Number of Full-time Paid Employees

.00 1.00 2.00 3.00 4.00 5.00 6.00 7 thru 10 11 thru

24

Number of full-time paid employees

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

2.8 Governance Issues

37. About 48.4 percent of wholesale establishments were not registered at all, while the

majority carried some form of registration. Of those who had not registered, almost 71.5

percent of wholesalers said that registration was not required. A further 4.1 percent cited

high registration fee as the reason for not registering the business. However, a little over 72

percent of enterprises were observed to provide receipts to customers, indicating that the vast

majority of wholesalers bear some form of tax liability.

Table 2.14: Registration Requirements

Frequency Percent Valid Percent Cumulative Percent

Valid No 242 48.4 48.4 48.4

Yes 258 51.6 51.6 100.0

Total 500 100.0 100.0

38. About 91 percent of respondents agreed, or strongly agreed with the statement that

they relied on the reputations of those that they entered into contracts with. Business

reputation was particularly important in Balochistan where 88 percent of respondents

strongly agreed with the need to ensure that a potential business partner has a good

reputation.

39. About 83 percent also agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that contracts

would prevent them from being cheated. Balochistan was also the province where a high

degree of confidence was expressed in contracts, with 52 percent of respondents strongly

agreeing with the statement that contracts prevent businessmen from being cheated. Alost

68.7 percent agreed or strongly agreed (with almost 16.6 percent strongly agreeing) with the

statement that the legal system was functional, in that they had confidence that their contracts

Wholesale Markets

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 21

and property rights would be upheld in a business dispute. More half of respondents (59.3

percent) disagreed with the statement that people from other baradaris or ethnic groups were

likely to cheat them, while 7.7 percent agreed with this statement.

Table 2.15: Governance Issues

Strongly

agree

Agree Disagree Strongly

disagree

I must rely on the reputation of those I enter into agreement

with.

% 47.4 44.0 8.5 .2

A contract will protect me from being cheated. % 23.0 60.4 15.4 1.2

The legal system will uphold my contract and property rights

in business disputes

% 16.6 52.1 26.9 4.4

People from other communities/baradaris are more likely to

cheat me.

% 7.7 33.0 50.2 9.1

People from other cities are more likely to cheat me. % 6.7 34.8 46.4 12.1

40. Disputes over late payments appear to be a common occurrence in wholesale trade, in

spite of the understanding of the prevalence of credit based transactions, with 53 percent of

respondents saying that they had been involved in such a dispute in the last year. The

incidence of serious crimes was relatively low, although about 17 percent of respondents also

reported theft cases. Perhaps due to the petty nature of disputes, the police is almost never

called in over half (54 percent) of even theft related issues were dealt with through

negotiation. In case of late payments, 91.3 percent of these were settled by negotiation.

2.9 Issues of Expansion

41. A little over half (51.8 percent) of wholesalers had considered expanding their

businesses within the same city, and almost 68 percent claimed that financial issues had

prevented them from putting their plans into operation. The lack of a reliable network of

partners was also cited by almost 17 percent of respondents as a reason for the restriction of

the business.

Table 2.16: Have you considered expanding your business to other regions?

Frequency Percent Valid Percent Cumulative Percent

Valid Yes, to same city 259 51.8 51.8 51.8

Yes, overseas 5 1.0 1.0 52.8

No 236 47.2 47.2 100.0

Total 500 100.0 100.0

42. As in the case of retailers, the proportion of respondents who claimed to have

considered entering into a partnership for business was very low at just 11.3 percent, with

almost 88.7 percent of respondents saying that they did not trust non family members when it

came to entering into partnerships. About a quarter of respondents said that they were

content with the current scale of the business and did not wish to expand. Only 10 percent of

respondents claimed to have any interest in entering into a franchise agreement with a foreign

owned business. For the majority who had not considered the option, 45.5 percent felt that

the type of franchises operating in the country did not work in areas relevant to their line of

work, while almost 20 percent did not want to enter into business dealings with strangers.

Almost 20 percent felt that franchise requirements were too difficult to fulfill, and almost 11

percent said that they did not know how to go about acquiring a franchise.

Survey Report on Domestic Commerce

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 22

2.10 Facilities for Wholesale Enterprises

43. About 73 percent of respondents said that the space they were operating in was

adequate for their needs, but 57.1 percent pointed out that additional space was not available,

even if they wanted to expand. In terms of conditions in shopping areas, enumerators noted

that in about 62.6 percent of cases, the road leading to the shopping area was in average

condition, while in 18 percent of cases the road was poor. The provision of parking space

was generally not up to standard, with enumerators recording that no parking space was

provided outside the shopping area in 37 percent of the locations, while in a further 34.6

percent of cases, parking space provided was inadequate to accommodate peak hour

shoppers. In 61.2 percent of cases, no encroachments were found outside shops.

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 23

Section 3

Conclusions

44. While the average revenue of wholesale businesses is higher than that of retail, the

wholesale sector in Pakistan, like the retail sector, is dominated by relatively small players.

As is the case for the retail sector, lack of access to finance was cited as a major constraint for

the expansion of individual businesses in the wholesale sector, but unlike retail, the low

quality of public infrastructure, and complications in the taxation system also figured quite

frequently in the responses. The lack of financing opportunities figures most prominently as

a barrier to entry and the excessive reliance on own or family savings restricts opportunities

in the wholesale business, and promotes a culture wherein only families with business

experience spawn new entrants. The sector does generate significant employment though,

particularly in Punjab and Sindh.

45. Wholesalers in Punjab and Sindh tended to trade in goods either produced in nearby

towns or villages, or obtained from nearby ports. Wholesalers in NWFP and Balochistan

had, of necessity, wider linkages outside their provinces. In addition, wholesale

establishments rarely use business services, relying instead on formal and informal kinship

networks for market intelligence and advertising. Similar networks are relied upon also for

dispute resolution.

46. In a wholesale sector where kinship networks are important for doing business and

dispute resolution is almost entirely informal, the lack of movement towards building

business conglomerates and taking advantage of economies of scale is very much an expected

outcome. Individual business volumes cannot increase significantly in an environment where

business dealings are rarely rooted in legal agreements.

3.1 Policy Recommendations

47. Key recommendations for the support of the wholesale sector include.

The banking sector has largely ignored trade and domestic commerce and at a time when

liquidity is high in the sector, banks must be encouraged to address the financial needs of

the trading community. Islamic finance institutions, which may use instruments more

palatable to stakeholders in this sector may be particularly well placed to service the

needs of the sector, given that many Islamic instruments of finance were designed

specifically to facilitate trading. This may involve devising somewhat innovative

instruments for financing, but given the size of the sector, and its growing importance in

the economy, this could potentially be a profitable venture.

It is imperative to develop small claims courts and enhance the capabilities of business

tribunals generally, to facilitate contract enforcement for domestic commerce. In the

absence of adequate measures for such enforcement, there is excessive reliance on

personal and family contacts, and dispute resolution, particularly for late payments, takes

Survey Report on Domestic Commerce

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt) 24

up time and effort on the part of the trading community as disputes are rarely taken to

legal authorities. The legal system is the cornerstone of the enabling environment for the

private sector to do business.

There is a need to facilitate the growth of business support services in the country for both

retail and wholesale markets. While some progress has been made in this regard in the

retail sector with the publication of business advisory reports on the retail sector in recent

years, there is very little information on the wholesale sector, given that foreign investors

are not primarily interested in wholesale trade. However, business support services are as

crucial, if not more so, for the wholesale sector as for retail, and the Ministry of

Commerce can encourage business support services by preparing databases of business

support services in key areas such as IT, accounting etc, and making such databases

available to export oriented enterprises as well as chambers of commerce and industry.

The Market Committee Act needs to be amended to allow a greater role for the private

sector in determining the day to day functioning of fruit and vegetable markets, expansion

plans etc.

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Note On The Edible Oil Milling Sector, Output, Value-Added and EmploymentDocument15 pagesA Note On The Edible Oil Milling Sector, Output, Value-Added and EmploymentInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Estimation of Elasticities of Substitution For CES Production Functions Using Aggregative Data On Selected Manufacturing Industries in PakistanDocument28 pagesEstimation of Elasticities of Substitution For CES Production Functions Using Aggregative Data On Selected Manufacturing Industries in PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Consumption Pattern of Major Food Items in Pakistan: Provincial Sectoral, and Inter-Temporal Differences, 1979-85"Document6 pagesConsumption Pattern of Major Food Items in Pakistan: Provincial Sectoral, and Inter-Temporal Differences, 1979-85"Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Estimation of Elasticities of Substitution For CES and VES Production Functions Using Firm-Level Data For Food-Processing Industries in PakistanDocument24 pagesEstimation of Elasticities of Substitution For CES and VES Production Functions Using Firm-Level Data For Food-Processing Industries in PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Rural-Urban Differences and The Stability of Consumption Behavior: An Inter-Temporal Analysis of The Household Income Expenditure Survey Data For The Period of 1963-85Document12 pagesRural-Urban Differences and The Stability of Consumption Behavior: An Inter-Temporal Analysis of The Household Income Expenditure Survey Data For The Period of 1963-85Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Choice of Techniques: The Case of Cottonseed Oil-Extraction in PakistanDocument10 pagesChoice of Techniques: The Case of Cottonseed Oil-Extraction in PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- List of PublicationsDocument1 pageList of PublicationsInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Differential Access and The Rural Credit Market in Pakistan: Some Recent EvidenceDocument8 pagesDifferential Access and The Rural Credit Market in Pakistan: Some Recent EvidenceInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Rural Poverty in Pakistan: Some Recent EvidenceDocument20 pagesRural Poverty in Pakistan: Some Recent EvidenceInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Some Tests For Differences in Consumption Patterns: The Impact of Remittances Using Household Income and Expenditure Survey 1987-1988Document13 pagesSome Tests For Differences in Consumption Patterns: The Impact of Remittances Using Household Income and Expenditure Survey 1987-1988Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Production Relations in The Large Scale Textile Manufacturing Sector of PakistanDocument16 pagesAn Analysis of Production Relations in The Large Scale Textile Manufacturing Sector of PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Capital Labour Substitution in The Large-Scale Food-Processing Industry in Pakistan: Some Recent EvidenceDocument12 pagesCapital Labour Substitution in The Large-Scale Food-Processing Industry in Pakistan: Some Recent EvidenceInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- The Role of Institutional Credit in The Agricultural Development of PakistanDocument10 pagesThe Role of Institutional Credit in The Agricultural Development of PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Role of Infaq in Poverty Alleviation in PakistanDocument18 pagesRole of Infaq in Poverty Alleviation in PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Transitions Out of Poverty: Drivers of Real Income Growth For The Poor in Rural PakistanDocument18 pagesTransitions Out of Poverty: Drivers of Real Income Growth For The Poor in Rural PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Production Functions For Wheat Farmers in Selected Districts in Pakistan: An Application of A Stochastic Frontier Production Function With Time-Varying Inefficiency EffectsDocument36 pagesProduction Functions For Wheat Farmers in Selected Districts in Pakistan: An Application of A Stochastic Frontier Production Function With Time-Varying Inefficiency EffectsInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Solving Organizational Problems With Intranet TechnologyDocument16 pagesSolving Organizational Problems With Intranet TechnologyInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Rural Poverty and Land Degradation: A Review of The Current State of KnowledgeDocument18 pagesRural Poverty and Land Degradation: A Review of The Current State of KnowledgeInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Its Impact On Poverty in PakistanDocument47 pagesGlobalization and Its Impact On Poverty in PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Female Time Allocation in Selected Districts of Rural PakistanDocument13 pagesDeterminants of Female Time Allocation in Selected Districts of Rural PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Rural Poverty and Credit Used: Evidence From PakistanDocument18 pagesRural Poverty and Credit Used: Evidence From PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Rethinking Development Strategy - The Importance of The Rural Non Farm Economy in Growth and Poverty Reduction in PakistanDocument16 pagesRethinking Development Strategy - The Importance of The Rural Non Farm Economy in Growth and Poverty Reduction in PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Poverty DimentioDocument14 pagesPoverty DimentioNaeem RaoNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitating Agriculture and Promoting Food Security Following The 2010 Pakistan Floods: Insights From The South Asian Experience.Document26 pagesRehabilitating Agriculture and Promoting Food Security Following The 2010 Pakistan Floods: Insights From The South Asian Experience.Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Rural Investment Climate Survey: Background and Sample Frame DesignDocument29 pagesPakistan Rural Investment Climate Survey: Background and Sample Frame DesignInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Tax Potential in NWFPDocument79 pagesTax Potential in NWFPInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- National Plan of Action For ChildrenDocument163 pagesNational Plan of Action For ChildrenInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- PunjabEconomicReport2007 08Document225 pagesPunjabEconomicReport2007 08Ahmad Mahmood Chaudhary100% (2)

- Access To Finance in NWFPDocument97 pagesAccess To Finance in NWFPInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- An Assessment of The Poverty Marker and Loan Classification Systems in Multilateral Development Banks With Lessons For The Asian Development BankDocument28 pagesAn Assessment of The Poverty Marker and Loan Classification Systems in Multilateral Development Banks With Lessons For The Asian Development BankInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- List of Reputable Firms in Karachi by CA Professionals Induction Team 1.2Document18 pagesList of Reputable Firms in Karachi by CA Professionals Induction Team 1.2M Ali ArifNo ratings yet

- Olper Milk Channel Management REPORTDocument26 pagesOlper Milk Channel Management REPORTSania NisarNo ratings yet

- List of Postal Codes in Pakistan - WikipediaDocument4 pagesList of Postal Codes in Pakistan - WikipediaRashidNo ratings yet

- 2954 - Factors Affecting Literacy RateDocument8 pages2954 - Factors Affecting Literacy RateMuhammad Farooq KokabNo ratings yet

- Seniority List Male Lecturers, BPS-18 Male (2018)Document82 pagesSeniority List Male Lecturers, BPS-18 Male (2018)Ammar Ahmed KhanNo ratings yet

- Lahore Education SectorDocument8 pagesLahore Education SectorMansoor BabarNo ratings yet

- NCOVID - List of Open BranchesDocument9 pagesNCOVID - List of Open Branchesaa bbNo ratings yet

- Karachi Eat-2017 (Sponsorship Form) - 03Document16 pagesKarachi Eat-2017 (Sponsorship Form) - 03Anas AdnanNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Excerpt: "Instant City: by Steve InskeepDocument5 pagesExcerpt: "Instant City: by Steve Inskeepwamu885No ratings yet

- Panel Hospital List AS On 02-01-2020Document8 pagesPanel Hospital List AS On 02-01-2020شہزاد حفیظNo ratings yet

- VoterListweb2016-2017 81Document1 pageVoterListweb2016-2017 81ShahzadNo ratings yet

- 111Document8 pages111Muhammad Nauman Nawaz100% (1)

- List of Licensed Lubricant Marketing Companies Lmcs Dated July 18 2018Document5 pagesList of Licensed Lubricant Marketing Companies Lmcs Dated July 18 2018Amya jones100% (1)

- List Pol Parties With AddressesDocument9 pagesList Pol Parties With AddressesBilal Ahmad0% (1)

- DARAZ PRICE CALCULATIONS (Fulfillment by Daraz) : Profit Margin AnalysisDocument5 pagesDARAZ PRICE CALCULATIONS (Fulfillment by Daraz) : Profit Margin AnalysisAhsanNo ratings yet

- Date Bank of Private Industry 1 DecDocument997 pagesDate Bank of Private Industry 1 Decshahid rasoolNo ratings yet

- Climate Past PapersDocument25 pagesClimate Past PapersMuhammad Ali Khan (AliXKhan)No ratings yet

- M.A. Jinnah RD.: @shahrahejinnahDocument9 pagesM.A. Jinnah RD.: @shahrahejinnahSAMRAH IQBALNo ratings yet

- Business Plan (OASIS)Document41 pagesBusiness Plan (OASIS)uzair97No ratings yet

- PanelDocument13 pagesPanelSaddam HussainNo ratings yet

- Summer Uniorm SRDocument7 pagesSummer Uniorm SRAJAR E ZEHRA KERRIONo ratings yet

- Illegal - Fake Universities & CampusesDocument6 pagesIllegal - Fake Universities & CampusesCar SecurityNo ratings yet

- German Companies in PakistanDocument5 pagesGerman Companies in PakistanMustafa100% (1)

- Kcaa Members ListDocument108 pagesKcaa Members ListMeraj Hussain100% (2)

- Transfer Posting - FBRDocument5 pagesTransfer Posting - FBRFarooq Omer KhanNo ratings yet

- All You Need To Know About KirachiDocument7 pagesAll You Need To Know About Kirachirunish venganzaNo ratings yet

- Useful Institutions in PakistanDocument21 pagesUseful Institutions in PakistanMustafaNo ratings yet

- List of CoDocument687 pagesList of Comadeelhassan67% (3)

- MIFI Retailer ListDocument9 pagesMIFI Retailer Listanon_68724319No ratings yet

- Jubilee Health Insurance List of Siscount Centres: S# Medical Centre Name City Address Discount % Discount On FacilityDocument4 pagesJubilee Health Insurance List of Siscount Centres: S# Medical Centre Name City Address Discount % Discount On FacilityAli ChundrigarNo ratings yet

- How to Start a Business: Mastering Small Business, What You Need to Know to Build and Grow It, from Scratch to Launch and How to Deal With LLC Taxes and Accounting (2 in 1)From EverandHow to Start a Business: Mastering Small Business, What You Need to Know to Build and Grow It, from Scratch to Launch and How to Deal With LLC Taxes and Accounting (2 in 1)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Finance Basics (HBR 20-Minute Manager Series)From EverandFinance Basics (HBR 20-Minute Manager Series)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (32)