Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Selvi PDF

Uploaded by

umdb22050 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5K views8 pagesThe document analyzes R.K. Narayan's short story "Selvi" and compares it to his novel "The Guide". It argues that "Selvi" can be seen as a rewriting of "The Guide" that shifts the focus to the female protagonist, Selvi, whose true self remains an enigma. Throughout the story, Selvi's husband and fans see her only as a body or performer, failing to grasp her inner consciousness. The story leaves many questions unanswered about Selvi's motives and feelings, mirroring her lack of self-development.

Original Description:

Original Title

Selvi.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document analyzes R.K. Narayan's short story "Selvi" and compares it to his novel "The Guide". It argues that "Selvi" can be seen as a rewriting of "The Guide" that shifts the focus to the female protagonist, Selvi, whose true self remains an enigma. Throughout the story, Selvi's husband and fans see her only as a body or performer, failing to grasp her inner consciousness. The story leaves many questions unanswered about Selvi's motives and feelings, mirroring her lack of self-development.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5K views8 pagesSelvi PDF

Uploaded by

umdb2205The document analyzes R.K. Narayan's short story "Selvi" and compares it to his novel "The Guide". It argues that "Selvi" can be seen as a rewriting of "The Guide" that shifts the focus to the female protagonist, Selvi, whose true self remains an enigma. Throughout the story, Selvi's husband and fans see her only as a body or performer, failing to grasp her inner consciousness. The story leaves many questions unanswered about Selvi's motives and feelings, mirroring her lack of self-development.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

1

R. K. NARAYAN S SELVI AS A REWRITING OF THE GUIDE

A book is the product of a different self from the self we manifest in our habits, in our social life, in our

vices. If we would try to understand that particular self, it is by searching our own bosoms, and trying

to reconstruct it there, that we may arrive at it.

(Marcel Proust, Against Saint-Beuve)

Selvi is one of the most intriguing short stories by R.K. Narayan, and possibly one of his

highest achievements within this genre. It was published for the first time in 1982 among

the new pieces in Malgudi Days, mostly a collection of reprints. Here Narayan proves a

keen and perceptive observer deploying irony and mystery to beguile the reader into an

exploration of the protagonists self. As it is with most Narayans works, in Selvi

Narayans irony creates a detachment that both intrigues and puzzles the reader. I shall

contend that this ironic detachment is strictly connected with a subtle use of knowledge

within the story, and that the whole story may be described as a partly disappointing

quest for Selvis personality.

The story line is very simple and it closely recalls part of the plot of Narayans most

renowned novel, The Guide. Selvi is a very talented singer from a lower class family in

Malgudi until Mohan, a former Gandhian freedom fighter, discovers her and becomes

both her husband and impresario. Under Mohans management Selvi achieves fame and

success, but when her mother dies alone in her poor house, Selvi decides to leave her

husband and her glamorous life to establish herself in her late mothers destitute dwelling

place, where she gives free concerts and apparently lives on offerings.

Likewise, in The Guide Raju, the protagonist, becomes Rosies lover and manager. Rosie is

a Bharata Natyam dancer who achieves fame and success thanks to the mans support. As

time goes by, the manager-lover loses interest in art and becomes all-absorbed in business.

Raju exploits Rosies art to make money until he gets into trouble and ends up in prison;

this puts an end to his affair with the dancer who becomes her own manager. In Selvi

2

the manager is actually a lawful husband, but otherwise the liaison that mingles love,

art and business is pretty much the same and much similar is the epilogue.

The Guide was published in 1958 and has been the most acclaimed of R.K. Narayans

novels ever since. There is no telling when R.K. Narayan actually wrote Selvi, but it is

certain that he did not publish it before 1982

1

. Why would Narayan go back to more or less

the same plot after over twenty years? It would not be surprising if the short narrative had

preceded the longer one, because this might be taken as an expansion of the former. But,

apparently, things stand the other way. Is there anything in The Guide Narayan was not

happy with? Is there anything he wanted to add to the story he had, in a way, already

told? Strangely enough to ever have addressed this question, and though secondary

bibliography on R.K. Narayan is rather rich, I have not been able to find any article dealing

even partially with Selvi.

A comparison between the two plots will hardly show any significant difference, nor will

a comparison between the themes touched by the narrative. Neither Karnatic music nor

Bharatha Natyam dance, pertaining to the short story and to the novel respectively, are

actually explored in depth. In both cases they actually stand for Art in general, or possibly

for traditional feminine art. Aesthetic issues or even the artists training are not mentioned

in the two narratives. In both narratives the point of view is masculine and the women do

not talk much. The marital relationship within the two couples does not really mark any

significant difference. Yet whereas, starting from the very title, in The Guide the

protagonist is Raju, the man, in Selvi the protagonist is the woman. The Guide is the

story of Raju, told partly by an omniscient narrator, partly by himself; Selvi is the story

of a woman, told by a semi-omniscient narrator with an internal focalization shifting from

Mohan, Selvis husband, to Varma, a representative of Selvis fans.

1

In the story Mohan boasts a very thick agenda, so that Selvi is not free for performances before 1982, implying

that it sounds a far off date. We learn that Mohan has a gallery of pictures in which Selvi is portrayed with

various celebrities such as Tito, Bulganin, John Kennedy, Charlie Chaplin (168), which seems to shift this

encounters to the Sixties. At the time of the epilogue we know that Selvi and Mohan have been married for

twenty years. This might mean that the story is set in the mid Seventies, which is probably also the time when it

was written, or revised.

3

The peculiar choice to bind the focalization to characters other than the alleged protagonist

triggers the readers curiosity to know something about Selvi as a person, her conscience.

Narayans technique creates a void beyond Selvis name. Her true self remains a mystery.

Selvi becomes the name people give to a body or to a performer, but never a character in

its own right. So much so that Selvis story develops like a detective story, around a

fundamental question who is Selvi, what are her motives? What is her true self? Selvi is

the protagonist in the same way the mystery may be the protagonist of a detective story.

Yet there is a major difference between a detective story and Selvi, namely that there is

no fictional detective here, no real truth seeker, at least none but the reader. In a way the

mystery remains partly unsolved, and Selvis true self inscrutable. In a classical crime

story the reader is usually led to share the detectives point of view and to sympathize

with him, at least in so far as both reader and detective search for the same truth. In

Selvi there is no character actually interested in the question and the detection is left to

the reader. Selvis choice to retire from the world may be read as a typical Hindu choice of

leaving the world of deception. Yet, being reminiscent of The Guide, Narayans readers

have a right to be sceptical about this interpretation. eventual choice is not said to be the

last step in a long spiritual journey.

Actually two characters might be interested in pursuing Selvis motives, but apparently

they both fail for opposite reasons. In fact both Mohan and Varma or those he stands for

are not interested in her self, but either in her body or in her gifts. Mohan is actually too

interested in her physical being (the colour of her skin, the pitch of her voice, the thickness

of her eyebrows) to actually understand her as a person, while her fans are actually too

interested in her art to get to know her. Selvis self between her body and her art can never

be grasped. Throughout the story Mohan thinks that Selvi should be grateful for his work,

and when he realizes that she is not, but, on the contrary, wishes for a different life, he

pronounces her a fool and an ungrateful wretch. Similarly Varma, the prototype of

her fans, sees her as a goddess and not as a human being. Possibly the only person who

ever saw Selvi as a human being was her mother, but we are never given a glimpse of her.

4

By self I mean here the same kind of consciousness Proust refers to, a reflection of ones

personality that is not public. Selvis art, like the book mentioned by Proust, is the product

of a different self from the self Selvi would manifest in her habits and to an omniscient

narrator in her thoughts. David Lodge (2002) claims that this self is the product of the

negotiation between ones soul and the environment, including ones body. A novel,

Lodge contends, is usually an exploration of this most subjective and inscrutable part of

the individual, and its value lies in this subjectivity, uniqueness. Narayan offers a

description of both Selvis art and body, but not of her self. It may be argued that the

readers search for Selvis self parallels her own quest, since her submissive attitude

prevented her from developing her consciousness. The important difference is, of course,

that the reader cannot be an agent in this development, but at most a sympathetic witness.

Still, at the end of the tale a number of questions do not find an answer: is Selvi conscious

of what she did? Is she happy with her new predicament? What exactly made her change

her mind? Does she feel guilty at leaving her husband?

Narayan is very careful that the reader does not sympathize with the deserted husband by

depicting him a selfish, hypocritical man who makes money out of Selvis talent and who

has betrayed in facts if not in words his former affiliation with the Gandhian

movement. However to the readers Mohans greatest sin is his neglect of his wifes

spiritual needs which originates in his lack of interest in her self; this is particularly

enervating for the reader who is more interested in Selvi than in Mohan.

Likewise the reader will only sympathize with Varma inasmuch as he is ill treated by

Mohan, but, again, he is never much more than an enthusiastic fan. To him Selvis

aloofness makes her similar to a deity, so much so that she is named The Goddess of

melody (169) and her fans hope to have a darshan

2

of Selvi (166); moreover, Varma

says that while Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, has been generous with him, now he

craves for the favour of Saraswathy, the goddess of arts, who is in *their+ midst as Selvi,

2

Darshan, vision, epiphany, is a word usually reserved to gods.

5

the divine singer(166). As with Mohan, his perception of the singer does not help to solve

the mystery of her true self.

The readers curiosity is enhanced by casual remarks on Selvis alleged secrets. It is told,

for instance, that nobody has ever seen the true colour of Selvis skin, and only Mohan

knows her real face; likewise Selvis marriage has taken place almost secretly. Every time

the narrator begins a description of Selvi, as a young girl or as a singer, or of her story, the

narration ends up relating the puzzled impression that this or that character (usually

Mohan) got of her. We find an example when Mohan shows her the new fancy house he is

about to buy. Everyone is impressed by the former East India Companys mansion, but

Selvi, who, only upon insistence, comments that the place is very big it adds to the

mysteries whether this is a reason to like or loathe the place.

This technique of focalising on minor characters leaving the protagonist unfocused is

rather peculiar to Selvi. One of the most striking differences between Narayan as a

novelist and Narayan as a short story writer is that as a novelist he explores the

consciousness of his characters in detail, while as a story teller, he entails a behaviourist

reading. Characters are mostly described from outside, and even when their thoughts are

described, they are usually sociable thoughts, unspoken sentences directed to someone,

not inner perceptions. Story readers can only make a guess at peoples thoughts judging

from their apparent behaviour

3

. Selvi is rather uncharacteristic in that it mixes these two

different stances; it does enter characters consciousness and describes their unexpressed

thoughts, but these characters are not the protagonist, who is observed only from outside.

This technique is frustrating for the reader who is eventually left in doubt.

Readers will seek clues about Selvi in her interaction with her husband and in the opinion

of her admirers. In the marital relationship, Selvi is by far the stronger, while Mohan

suffers from an inferiority complex. Consequently he tries his best to assert his own

importance by Selvis admirers and often prevails upon her for no other reason than to be

3

Obviously there are exceptions to this general statement. Fathers Help is one such, but this sketch was

probably written for inclusion into Swami and Friends, with which it shares the protagonist and the setting.

6

regarded as her guru. In fact, as she will state quite bluntly toward the end of the story, he

has never been her guru. It is worth noting that despite the apparent modernity of his

management, the old Gandhian freedom fighter seeks a quite traditional position, which

only Selvi could grant him. In fact one of the reasons for Selvis strength may be that she

does not have to compromise with the petty details of life and her predicament is strongly

rooted in the sacred tradition of Karnatic music. Even her meekness may be interpreted

either as a part of her character or a sort of conscious asceticism.

Varma sees in Selvis art a reflection of a superior soul, while Mohan only saw a body; but

if we follow Prousts cue that the work of art is the product of a different self than the one

expressed in our habits, neither Varma nor Mohan, have actually sought Selvis self in the

right place.

In the authors introduction to the tales Narayan states that he

discover[s] a story when a personality passes through a crisis of spirit or circumstances.

In the following tales, almost invariably the central character faces some kind of crisis

and either resolves it or lives with it. (MD 8).

Thus a crisis may be the moment when ones self is revealed. In the case of Selvi the crisis

does come when the womans mother suddenly dies. Selvi had repeatedly expressed her

wish to go and see the mother, but Mohan had apparently persuaded her to postpone the

visit. When Selvi reaches her mothers modest house, she decides not go back with Mohan.

The narrator does not intrude into Selvis thoughts, but, sticking to Mohans point of view,

simply recounts her actions.

In the end it is not possible to know what Selvi really thought and to apprehend her self, it

can only be surmised. We dont know when exactly Selvi has decided never to go home to

her husband again whether she has ever had doubts about this decision. In fact, while in

The Guide Rosie is actually rather loyal to Raju and leaves him only when there is nothing

more to be done to help him out of prison, Selvi leaves her husband quite suddenly and

without explanation. After all she had let him think that she was happy with their life and

had never tried to change her plight. The reader can only guess her thoughts. The

7

detective story within Selvi has had only a partial solution: readers learn that she was

unhappy with her husband and that she never considered him as a guru. But this is

probably too easy an explanation; Selvi appears to be the female counterpart of Raju. Her

story is the story of one who has achieved a spiritual enlightenment through art, and it is

hard to describe the consciousness of a saint without making him/her seem ordinary

consequently Narayan opts for an external focalization. Even the Gospel hardly offers a

glimpse into Jesus mind.

Narayans own novel The Guide, leaves its protagonists thoughts the very moment he is

achieving an illumination. Yet an inevitable corollary of external focalization is doubt and

unreliability and we remain unsure of Rajus fate. Likewise those who see in Selvi a saint

are as justified to do so as Mohan is justified in calling her an ungrateful wretch. In fact,

whether her choice to leave her former life for a life of retirement in Vinayak Mudali street

is a sudden inspiration, or a spiritual renunciation to luxuries, or a form of commitment to

art, or even a passive atonement for neglecting her mother, will forever remain a mystery.

It is impossible, and probably not even desirable, to know what there is deep inside

people. Ironically the search for knowledge of Selvis real truth remains unfulfilled, like

her listeners enjoy her music without ever talking to her, we can only enjoy her story and

be content to speculate about the unattainability of ultimate truths.

Works Cited

Almond, Ian. Darker Shades of Malgudi: Solitary Figures of Modernity in the Stories of

R.K. Narayan. Journal of Commonwealth Literature 36.2 (2001): 107-16.

Lodge, David. Consciousness and the Novel. London: Penguin, 2003.

Mathur, O. P. The Guide: A Study in Cultural Ambivalence. The Literary Endeavour: A

Quarterly Journal Devoted to English Studies 3.3-4 (1982): 70-79.

Narayan, R.K. Selvi. Malgudi Days. London: Penguin, 1982.

8

Proust, Marcel. Against Sainte-Beuve and other Essays, London: Penguin, 1988.

Rothfork, John. Hindu Mysticism in the Twentieth Century: R. K. Narayan's the Guide.

Philological Quarterly 62.1 (1983): 31-43.

Singh Ram, Sewak, and Krishnaswami Narayan Rasipuram. R. K. Narayan-the Guide. Some

Aspects. Delhi: Doaba House, 1971.

You might also like

- Analysis of Standing Female Nude - Gaayathri GaneshDocument2 pagesAnalysis of Standing Female Nude - Gaayathri GaneshGaayathri GaneshNo ratings yet

- How Did Mr. Sivasanker Engage A Domestic Servant ? What Were The Chores That The Domestic Servant Perform ?Document2 pagesHow Did Mr. Sivasanker Engage A Domestic Servant ? What Were The Chores That The Domestic Servant Perform ?Ìßhã BaruaNo ratings yet

- Waiting For Godot PDFDocument23 pagesWaiting For Godot PDFVellen Nydia.FlorenceNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Nissim Ezekiel and Eunice de Souza: 1.0 ObjectivesDocument14 pagesUnit 1 Nissim Ezekiel and Eunice de Souza: 1.0 ObjectivesJasmineNo ratings yet

- I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings LitChartDocument24 pagesI Know Why The Caged Bird Sings LitChartDs AdithyaNo ratings yet

- 15 - 7w894444. AK Omprakash Valmiki PDFDocument6 pages15 - 7w894444. AK Omprakash Valmiki PDFLava LoonNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis "Introduction" To The Songs of InnocenceDocument4 pagesCritical Analysis "Introduction" To The Songs of Innocencenoddy_tuliNo ratings yet

- Bravely Fought The QueenDocument5 pagesBravely Fought The QueenSabir Alam Sardar100% (1)

- Analysis of Trail of The Green BlazerDocument2 pagesAnalysis of Trail of The Green BlazerTeh Zi YeeNo ratings yet

- Appropriateness of The TitleDocument5 pagesAppropriateness of The TitleSanjay Kumar SinhaNo ratings yet

- Character Development of NoraDocument4 pagesCharacter Development of Noraesha khanNo ratings yet

- Alice AdulthoodDocument8 pagesAlice Adulthoodapi-254001250100% (1)

- Diary As A Dramatic DeviceDocument1 pageDiary As A Dramatic DeviceMahin Mondal100% (1)

- LeelaDocument4 pagesLeelaTANBIR RAHAMANNo ratings yet

- Othello EssayDocument5 pagesOthello EssayHye WonNo ratings yet

- Mending Wall Robert FrostDocument20 pagesMending Wall Robert FrostFawzia Firza100% (1)

- Role of Gods in The Good Woman of SetzuanDocument2 pagesRole of Gods in The Good Woman of SetzuanRohit Saha100% (1)

- S.N. Hingu - E - Pathshala - Critically Evaluate The Title of The Novel - GodanDocument3 pagesS.N. Hingu - E - Pathshala - Critically Evaluate The Title of The Novel - Godanaishwary thakurNo ratings yet

- DaddyDocument2 pagesDaddyricalindayuNo ratings yet

- Charudatta in MricchakatikaDocument3 pagesCharudatta in MricchakatikaIndrajit RanaNo ratings yet

- Viola's Character SketchDocument2 pagesViola's Character Sketchnikiforevaeny80% (5)

- The Merchant of Venice (Workbook)Document64 pagesThe Merchant of Venice (Workbook)Ishan Haldar100% (1)

- Bonsai and Dwarfish Maturity in Bravely Fought The QueenDocument2 pagesBonsai and Dwarfish Maturity in Bravely Fought The QueenSomenath DeyNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of The PoemDocument2 pagesAn Analysis of The PoemDayanand Gowda Kr100% (2)

- Keki N DaruwallaDocument26 pagesKeki N DaruwallaMallNo ratings yet

- Ode To PsycheDocument7 pagesOde To PsychelucienneNo ratings yet

- 046 Death and The Kings HorsemenDocument2 pages046 Death and The Kings HorsemenMisajNo ratings yet

- Gender Performativity in Shakespeare's Twelfth Night A Feminist StudyDocument9 pagesGender Performativity in Shakespeare's Twelfth Night A Feminist StudyHilga Clararissa A.SNo ratings yet

- A Character Analysis of Elizabeth BennetDocument4 pagesA Character Analysis of Elizabeth BennetIjan Izan33% (3)

- Dse - Partition Literature B.A. (Hons.) English VI SemesterDocument11 pagesDse - Partition Literature B.A. (Hons.) English VI SemesterSajal DasNo ratings yet

- Alam S Own HouseDocument3 pagesAlam S Own HouseZenith RoyNo ratings yet

- Absurdism and Waiting For GodotDocument8 pagesAbsurdism and Waiting For GodotumarNo ratings yet

- Eco - Cultural Consciousness in R.K. Narayan's Writings (Paper)Document6 pagesEco - Cultural Consciousness in R.K. Narayan's Writings (Paper)Kumaresan RamalingamNo ratings yet

- I Know Why The Caged Bird SingsDocument6 pagesI Know Why The Caged Bird SingsShreyash Thamke100% (1)

- RIVER ScribdDocument7 pagesRIVER ScribdshettyNo ratings yet

- Finding Sense Behind Nonsense in Select Poems of Sukumar RayDocument10 pagesFinding Sense Behind Nonsense in Select Poems of Sukumar RayRindon KNo ratings yet

- Critical AppreciationDocument13 pagesCritical AppreciationSaleem Raza100% (1)

- Mahesh DattaniDocument4 pagesMahesh DattaniSatyam PathakNo ratings yet

- Self Portrait by ADocument4 pagesSelf Portrait by ASyeda Fatima GilaniNo ratings yet

- Self-Help To ISC The TempestDocument72 pagesSelf-Help To ISC The TempestUuhuhhjhNo ratings yet

- Revolving Days: - David MaloufDocument5 pagesRevolving Days: - David MaloufHimank Saklecha100% (1)

- The Spanish TragedyDocument6 pagesThe Spanish TragedyAris Chakma100% (2)

- Critical Analysis Swami and Friends by HDocument2 pagesCritical Analysis Swami and Friends by HParthiva SinhaNo ratings yet

- Absence in Mahesh Dattani's Bravely Fought The QueenDocument16 pagesAbsence in Mahesh Dattani's Bravely Fought The QueenShirsha100% (1)

- A Room of Ones Own LitChartDocument28 pagesA Room of Ones Own LitChartPrep hypsNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 10 English Literature Notes PDFDocument30 pagesCBSE Class 10 English Literature Notes PDFSudha PandeyNo ratings yet

- The Girl Who Can - Long NotesDocument3 pagesThe Girl Who Can - Long NotesAnimesh BhakatNo ratings yet

- Poems NotesDocument33 pagesPoems NotesAbhishek M N0% (1)

- Significance of The TitleDocument5 pagesSignificance of The TitleDaffodilNo ratings yet

- Bravely Fought The QueenDocument31 pagesBravely Fought The QueenRajarshi Halder0% (1)

- Ramnik GandhiDocument1 pageRamnik GandhiMahin Mondal0% (1)

- Doll - Significance of The Tital Dolls HouseDocument2 pagesDoll - Significance of The Tital Dolls HouseArif Nawaz100% (1)

- Dawn at Puri AnalysisDocument2 pagesDawn at Puri AnalysisAravind R Nair33% (3)

- SpencerDocument7 pagesSpencerJesi GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Obituary by A K RamanujanDocument5 pagesObituary by A K RamanujanAmith amithNo ratings yet

- Humour in R K Narayan's Swami and FriendsDocument5 pagesHumour in R K Narayan's Swami and FriendsAisha RahatNo ratings yet

- Delhi Is Not Far As An Instance of Popular LiteratureDocument5 pagesDelhi Is Not Far As An Instance of Popular LiteratureTanmoy Sarkar Ghosh100% (1)

- Nissim Ezekiel - Night of The Scorpion PDFDocument4 pagesNissim Ezekiel - Night of The Scorpion PDFSharad Chaudhary100% (1)

- The Indian Emperor: "Boldness is a mask for fear, however great."From EverandThe Indian Emperor: "Boldness is a mask for fear, however great."No ratings yet

- The Bird of Time - Songs of Life, Death & The Spring: With a Chapter from 'Studies of Contemporary Poets' by Mary C. SturgeonFrom EverandThe Bird of Time - Songs of Life, Death & The Spring: With a Chapter from 'Studies of Contemporary Poets' by Mary C. SturgeonNo ratings yet

- CCC DutiesDocument2 pagesCCC Dutiesumdb2205No ratings yet

- JW Online Library DownloadDocument1 pageJW Online Library Downloadumdb2205No ratings yet

- Press ReleaseDocument2 pagesPress Releaseumdb2205No ratings yet

- Bus Route No.27-PDocument22 pagesBus Route No.27-Pumdb2205No ratings yet

- Indian 500 and 1000 Rupee Note Demonetisation - WikipediaDocument20 pagesIndian 500 and 1000 Rupee Note Demonetisation - Wikipediaumdb2205100% (1)

- WS Class 3 PDFDocument61 pagesWS Class 3 PDFumdb2205100% (1)

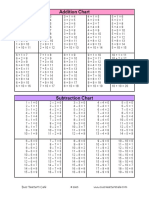

- Math Charts PDFDocument2 pagesMath Charts PDFumdb2205No ratings yet

- Sêh $Uûñ»Q Ô - ' Uû≤Y√ ±/Qt <Ë (Ï ªdüetdü´/Ô - 'Μ <Äèwæº Kõ) <Ë›+!Document4 pagesSêh $Uûñ»Q Ô - ' Uû≤Y√ ±/Qt <Ë (Ï ªdüetdü´/Ô - 'Μ <Äèwæº Kõ) <Ë›+!umdb2205No ratings yet

- DNT DelhiMeet01Document1 pageDNT DelhiMeet01umdb2205No ratings yet

- HRF Pamphlet-Balagopal Memorial Meet-2016Document2 pagesHRF Pamphlet-Balagopal Memorial Meet-2016umdb2205No ratings yet

- Salwa Judum On Its Way OutDocument1 pageSalwa Judum On Its Way Outumdb2205No ratings yet

- 1-10 Add Chart BlankDocument1 page1-10 Add Chart Blankumdb2205No ratings yet

- Legal WritingDocument1 pageLegal Writingumdb2205No ratings yet

- Navy A 2Document1 pageNavy A 2umdb2205No ratings yet

- Áfl Mê $pàyï Wôû Áfl Ôë Àô F-È $ Î !Document4 pagesÁfl Mê $pàyï Wôû Áfl Ôë Àô F-È $ Î !umdb2205No ratings yet

- Pamphlet On RTE ActDocument2 pagesPamphlet On RTE Actumdb2205No ratings yet

- Ed Food QuotaDocument1 pageEd Food Quotaumdb2205No ratings yet

- HRF 4th Mahasabhalu PamphletDocument4 pagesHRF 4th Mahasabhalu Pamphletumdb2205No ratings yet

- Foodgrain For PoorDocument1 pageFoodgrain For Poorumdb2205No ratings yet

- Ap Value Added Tax Act - 2005Document78 pagesAp Value Added Tax Act - 2005umdb2205No ratings yet

- STORIESDocument18 pagesSTORIESHaRa TNo ratings yet

- Wapda CSR 2013 Zone 3Document245 pagesWapda CSR 2013 Zone 3Naveed Shaheen91% (11)

- User Manual PocketBookDocument74 pagesUser Manual PocketBookmisu2001No ratings yet

- Marisa Wolf Final New ResumeDocument2 pagesMarisa Wolf Final New Resumeapi-403499166No ratings yet

- Statistics For Criminology and Criminal Justice (Jacinta M. Gau)Document559 pagesStatistics For Criminology and Criminal Justice (Jacinta M. Gau)Mark Nelson Pano ParmaNo ratings yet

- Metro Depot: (Aar 422) Pre-Thesis SeminarDocument3 pagesMetro Depot: (Aar 422) Pre-Thesis SeminarSri VirimchiNo ratings yet

- Test Bank Bank For Advanced Accounting 1 E by Bline 382235889 Test Bank Bank For Advanced Accounting 1 E by BlineDocument31 pagesTest Bank Bank For Advanced Accounting 1 E by Bline 382235889 Test Bank Bank For Advanced Accounting 1 E by BlineDe GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Device InfoDocument3 pagesDevice InfoGrig TeoNo ratings yet

- Ashfaque Ahmed-The SAP Materials Management Handbook-Auerbach Publications, CRC Press (2014)Document36 pagesAshfaque Ahmed-The SAP Materials Management Handbook-Auerbach Publications, CRC Press (2014)surajnayak77No ratings yet

- 250 Conversation StartersDocument28 pages250 Conversation StartersmuleNo ratings yet

- Christine Remembered That Today Is The Birthday of Her BossDocument1 pageChristine Remembered That Today Is The Birthday of Her BossA.No ratings yet

- DesignDocument402 pagesDesignEduard BoleaNo ratings yet

- How To Spend An Hour A Day in Prayer - Matthew 26:40-41Document1 pageHow To Spend An Hour A Day in Prayer - Matthew 26:40-41Steve GainesNo ratings yet

- Course Information2009 2010Document4 pagesCourse Information2009 2010shihabnittNo ratings yet

- BROMINE Safety Handbook - Web FinalDocument110 pagesBROMINE Safety Handbook - Web Finalmonil panchalNo ratings yet

- Cpa f1.1 - Business Mathematics & Quantitative Methods - Study ManualDocument573 pagesCpa f1.1 - Business Mathematics & Quantitative Methods - Study ManualMarcellin MarcaNo ratings yet

- TPT 510 Topic 3 - Warehouse in Relief OperationDocument41 pagesTPT 510 Topic 3 - Warehouse in Relief OperationDR ABDUL KHABIR RAHMATNo ratings yet

- Pipetite: Pipetite Forms A Flexible, Sanitary Seal That Allows For Pipeline MovementDocument4 pagesPipetite: Pipetite Forms A Flexible, Sanitary Seal That Allows For Pipeline MovementAngela SeyerNo ratings yet

- Учебный предметDocument2 pagesУчебный предметorang shabdizNo ratings yet

- T HR El 20003 ST PDFDocument20 pagesT HR El 20003 ST PDFAngling Dharma100% (1)

- Bachelors of Engineering: Action Research Project - 1Document18 pagesBachelors of Engineering: Action Research Project - 1manasi rathiNo ratings yet

- S P 01958 Version 2 EPD OVO ArmchairDocument16 pagesS P 01958 Version 2 EPD OVO ArmchairboiNo ratings yet

- Solow 5e Web SolutionsDocument58 pagesSolow 5e Web SolutionsOscar VelezNo ratings yet

- High School Department PAASCU Accredited Academic Year 2017 - 2018Document6 pagesHigh School Department PAASCU Accredited Academic Year 2017 - 2018Kevin T. OnaroNo ratings yet

- Norman K. Denzin - The Cinematic Society - The Voyeur's Gaze (1995) PDFDocument584 pagesNorman K. Denzin - The Cinematic Society - The Voyeur's Gaze (1995) PDFjuan guerra0% (1)

- The Names of Allah and Their ReflectionsDocument98 pagesThe Names of Allah and Their ReflectionsSuleyman HldNo ratings yet

- Organic Food Business in India A Survey of CompaniDocument19 pagesOrganic Food Business in India A Survey of CompaniShravan KemturNo ratings yet

- Action Research in Araling PanlipunanDocument3 pagesAction Research in Araling PanlipunanLotisBlanca94% (17)

- THE PERFECT DAY Compressed 1 PDFDocument218 pagesTHE PERFECT DAY Compressed 1 PDFMariaNo ratings yet

- Root End Filling MaterialsDocument9 pagesRoot End Filling MaterialsRuchi ShahNo ratings yet