Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cases For Usufruct

Uploaded by

Christopher Anderson0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

45 views15 pagesProperty

Original Title

Cases for Usufruct

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentProperty

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

45 views15 pagesCases For Usufruct

Uploaded by

Christopher AndersonProperty

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 15

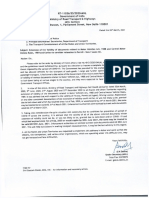

CASES in USUFRUCT

G.R. No. L-123 December 12, 1945

JOSEFA FABIE, petitioner,

vs.

JOSE GUTIERREZ DAVID, Judge of First Instance of Manila, NGO BOO

SOO and JUAN GREY, respondents.

OZAETA, J.:

The petitioner Josefa Fabie is the usufructuary of the income of certain

houses located at 372-376 Santo Cristo, Binondo, and 950-956 Ongpin,

Santa Cruz, Manila, under the ninth clause of the will of the deceased

Rosario Fabie y Grey, which textually reads as follows:

NOVENO. Lego a mi ahijada menor de edad, Maria Josefa de la

Paz Fabie, en usufructo vitalicio las rentas de las fincas situadas

en la Calle Santo Cristo Numeros 372 al 376 del Disrito de

Binondo, de esta Ciudad de Manila, descrita en el Certificado

Original de Titulo No. 3824; y en la Calle Ongpin, Numeros 950 al

956 del Distrito de Santa Cruz, Manila descrita en el Certificado

Original de Titulo No. 5030, expedidos por el Registrador de

Titulos de Manila, y prohibo enajene, hipoteque, permute o

transfiera de algun modo mientras que ella sea menor de edad.

Nombro a Serafin Fabie Macario, mi primo por linea paterna

tutor de la persona y bienes de mi ahijada menor, Maria Josefa de

la Paz Fabie.

The owner of Santo Cristo property abovementioned is the respondent

Juan Grey, while those of the Ongpin property are other person not

concern herein. Previous to September 1944 litigation arose between

Josefa Fabie as plaintiff and Juan Grey as defendant and the owner of the

Ongpin property as intervenors, involving the administration of the

houses mentioned in clause 9 of the will above quoted (civil case No.

1659 of the Court of First Instance of Manila). That suit was decided by

the court on September 2, 1944, upon a stipulation in writing submitted

by the parties to and approved by the court. The pertinent portions of

said stipulation read as follows:

(4) Heretofore, the rent of said properties have been collected at

times by the respective owners of the properties, at other times

by the usufructuary, and lastly by the defendant Juan Grey as

agent under a written agreement dated March 31, 1942, between

the owners of both properties and the usufructuary.

(5) When the rents were collected by the owners, the net

amounts thereof were duly paid to the usufructuary after the

expenses for real estate taxes, repairs and insurance premiums,

including the documentary stamps, on the properties and the

expenses of collecting the rents had been deducted, and certain

amount set aside as a reserve for contingent liabilities. When the

rents were collected by the usufructuary, she herself paid the

expenses aforesaid. When the rents are collected by the

defendant Juan Grey under the agreement of March 31, 1942, the

net amounts thereof were duly paid to the usufructuary, after

deducting and setting aside the items aforesaid, monthly, until

the month of October 1943, when the usufructuary refused to

continue with the agreement of March 31, 1942.

x x x x x x x x x

II. The parties hereto jointly petition the Court to render

judgment adopting the foregoing as finding of facts and disposing

that:

(8) Beginning with the month of September 1944, the

usufructuary shall collect all the rents of the both the Sto. Cristo

and the Ongpin properties.

(9) The usufructuary shall, at her own cost and expense, pay all

the real estate taxes, special assessments, and insurance

premiums, including the documentary stamps, and make all the

necessary repairs on each of the properties, promptly when due

or, in the case of repairs, when the necessary, giving immediate,

written notice to the owner or owners of the property concerned

after making such payment or repairs. In case of default on the

part of the usufructuary, the respective owners of the properties

shall have the right to make the necessary payment, including

penalties and interest, if any, on the taxes and special

assessments, and the repairs and in that event the owner or

owners shall entitled to collect all subsequent rents of the

property concerned until the amount paid by him or them and

the expenses of collection are fully covered thereby, after which

the usufructuary shall again collect the rents in accordance

herewith.

(10) The foregoing shall be in effect during the term of the

usufruct and shall be binding on the successors and assigns of

each of the parties.

(11) Nothing herein shall be understood as affecting any right

which the respective owners of the properties have or may have

as such and which is not specifically the subject of this

stipulation.

In June 1945 Josefa Fabie commenced an action of unlawful detainer

against the herein respondent Ngo Boo Soo (who says that his correct

name is Ngo Soo), alleging in her amended complaint that the defendant

is occupying the premises located at 372-376 Santo Cristo on a month-to

month rental payable in advance not latter than the 5th of each month;

that she is the administratrix and usufructuary of said premises; "that

the defendant offered to pay P300 monthly rent payable in advance not

later than the 5th of every month, beginning the month of April 1945, for

the said of premises including the one door which said defendant,

without plaintiff's consent and contrary to their agreement, had

subleased to another Chinese, but plaintiff refused, based on the fact that

the herein plaintiff very badly needs the said house to live in, as her

house was burned by the Japanese on the occasion of the entry of the

American liberators in the City and which was located then at No. 38

Flores, Dominga, Pasay; that defendant was duly notified on March 24

and April 14, 1945, to leave the said premises, but he refused"; and she

prayed for judgment of eviction and for unpaid rentals.

The defendant answered alleging that he was and since 1908 had been a

tenant of the premises in question, which he was using and had always

used principally as a store and secondarily for living quarters; that he

was renting it from its owner and administrator Juan Grey; "that plaintiff

is merely the usufructuary of the income therefrom, and by agreement

between her and said owner, which is embodied in a final judgment of

the Court of First Instance of Manila, her only right as usufructuary of

the income is to receive the whole of such income; that she has no right

or authority to eject tenants, such right being in the owner and

administrator of the house, the aforesaid Juan Grey, who has heretofore

petitioned this Court for permission to intervene in this action; that

plaintiff herein has never had possession of said property; that

defendant's lease contract with the owner of the house is for 5-year

period, with renewal option at the end of each period, and that his

present lease due to expire on December 31, 1945 . . .; that on June 1,

1945, defendant made a written offer to plaintiff to compromise and

settle the question of the amount of rent to be paid by defendant . . . but

said plaintiff rejected the same for no valid reason whatever and

instituted the present action; that the reason plaintiff desires to eject

defendant from the property is that she wishes to lease the same to

other persons for a higher rent, ignoring the fact that as usufructuary of

the income of the property she has no right to lease the property; that

the defendant has subleased no part of the house to any person

whomsoever.

Juan Grey intervened in the unlawful detainer suit, alleging in his

complaint in intervention that he is the sole and absolute owner of the

premises in question; that the plaintiff Josefa Fabie is the usufructuary of

the income of said premises; by virtue of a contract between him and the

intervenor which will expire on December 31, 1945, with the option to

renew it for another period of five years from and after said date; that

under the agreement between the intervenor and plaintiff Josefa Fabie in

civil case No. 1659 of the Court of First Instance of Manila, which was

approved by the court and incorporated in its decision of September 2,

1944, the only right recognized in favor of Josefa Fabie as usufructuary

of the income of said premises is to receive the rents therefrom when

due; and that as usufructuary she has no right nor authority to

administer the said premises nor to lease them nor to evict tenants,

which right and authority are vested in the intervenor as owner of the

premises.

The municipal court (Judge Mariano Nable presiding) found that under

paragraph 9 of the stipulation incorporated in the decision of the Court

First Instance of Manila in civil; case No. 1659, the plaintiff usufructuary

is the administratrix of the premises in question, and that the plaintiff

had proved her cause. Judgment was accordingly rendered ordering the

defendant Ngo Soo to vacate the premises and to pay the rents at the

rate of P137.50 a month beginning April 1, 1945. The complaint in

intervention was dismissed.

Upon appeal to the Court of First Instance of Manila the latter (thru

Judge Arsenio P. Dizon) dismissed the case for the following reason:

"The main issue *** is not a mere question of possession but precisely

who is entitled to administer the property subject matter of this case and

who should be the tenant, and the conditions of the lease. These issues

were beyond the jurisdiction of the municipal court. This being case, this

Court, as appellate court, is likewise without jurisdiction to take

cognizance of the present case." A motion for reconsideration filed by

the plaintiff was denied by Judge Jose Gutierrez David, who sustained the

opinion of Judge Dizon.lawphi1.net

The present original action was instituted in this Court by Josefa Fabie to

annul the order of the dismissal and to require to the Court of First

Instance to try and decide the case on the merits. The petitioner further

prays that the appeal of the intervenor Juan Grey be declared out of time

on the ground that he receive copy of the decision on August 3 but did

not file his notice of appeal until August 25, 1945.

1. The first question to determine is whether the action instituted by the

petitioner Josefa Fabie in the municipal court is a purely possessory

action and as such within the jurisdiction of said court, or an action

founded on property right and therefore beyond the jurisdiction of the

municipal court. In other words, is it an action of unlawful detainer

within the purview of section 1 of Rule 72, or an action involving the title

to or the respective interests of the parties in the property subject of the

litigation?

Said section 1 of Rule 72 provides that "a landlord, vendor, vendee, or

other person against whom the possession of any land or building is

unlawfully withheld after the expiration or termination of the right to

hold possession, by virtue of any contract, express or implied, or the

legal representatives or assigns of any such landlord, vendor vendee, or

other person, may, at any time within one year after such unlawful

deprivation of withholding of possession, bring an action in the proper

inferior court against the person or persons unlawfully withholding or

depriving of possession, or any person or persons claiming under them,

for the restitution of such possession, together with the damages and

costs."

It is admitted by the parties that the petitioner Josefa Fabie is the

usufructuary of the income of the property in question and that the

respondent Juan Grey is the owner thereof. It is likewise admitted that

by virtue of a final judgment entered in civil case No. 1659 of the Court of

First Instance of Manila between the usufructuary and the owner, the

former has the right to collect all the rents of said property for herself

with the obligation on her part to pay all the real estate taxes, special

assessments, and insurance premiums, and make all necessary repairs

thereon, and in case default on her part the owner shall have the right to

do all those things, in which event he shall be entitled to collect all

subsequent rents of the property concerned until the amount paid by

him and the expenses of collection are fully satisfied, after which the

usufructuary shall again collect the rents. There is therefore no dispute

as to the title to or the respective interests of the parties in the property

in question. The naked title to the property is to admittedly in the

respondent Juan Grey, but the right to all the rents thereof, with the

obligation to pay the taxes and insurance premiums and make the

necessary repairs, is, also admittedly, vested in the usufructuary, the

petitioner Josefa Fabie, during her lifetime. The only question between

the plaintiff and the intervenor is: Who has the right to manage or

administer the property to select the tenant and to fix the amount of

the rent? Whoever has that right has the right to the control and

possession of the property in question, regardless of the title thereto.

Therefore, the action is purely possessory and not one in any way

involving the title to the property. Indeed, the averments and the prayer

of the complaint filed in the municipal court so indicate, and as a matter

of fact the defendant Ngo Soo does not pretend to be the owner of the

property, but on the contrary admits to be a mere tenant thereof. We

have repeatedly held that in determining whether an action of this kind

is within the original jurisdiction of the municipal court or of the Court of

First Instance, the averments of the complaint and the character of the

relief sought are primarily to be consulted; that the defendant in such an

action cannot defeat the jurisdiction of the justice of the peace or

municipal court by setting up title in himself; and that the factor which

defeats the jurisdiction of said court is the necessity to adjudicate the

question of title. (Mediran vs. Villanueva, 37 Phil., 752, 759;

Medel vs.Militante, 41 Phil., 526, 529; Sevilla vs. Tolentino, 51 Phil., 333;

Supia and Batioco vs. Quintero and Ayala, 59 Phil., 312;

Lizo vs. Carandang, G.R. No. 47833, 2 Off. Gaz., 302; Aguilar vs. Cabrera

and Flameo, G.R. No. 49129.)

The Court of First Instance was evidently confused and led to

misconstrue the real issue by the complaint in intervention of Juan Grey,

who, allying himself with the defendant Ngo Soo, claimed that he is the

administrator of the property with the right to select the tenant and

dictate the conditions of the lease, thereby implying that it was he and

not the plaintiff Josefa Fabie who had the right to bring the action and

oust the tenant if necessary. For the guidance of that court and to obviate

such confusion in its disposal of the case on the merits, we deem it

necessary and proper to construe the judgment entered by the Court of

First Instance of Manila in civil case No. 1659, entitled "Josefa Fabie and

Jose Carandang, plaintiffs, vs. Juan Grey, defendant, and Nieves G. Vda. de

Grey, et al., intervenors-defendants" which judgment was pleaded by the

herein respondents Juan Grey and Ngo Soo in the municipal court.

According the decision, copy of which was submitted to this Court as

Appendix F of the petition and as Annex 1 of the answer, there was an

agreement, dated March 31, 1942, between the usufructuary Josefa

Fabie and the owner Juan Grey whereby the latter as agent collected the

rents of the property in question and delivered the same to the

usufructuary after deducting the expenses for taxes, repairs, insurance

premiums and the expenses of collection; that in the month of October

1943 the usufructuary refused to continue with the said agreement of

March 31, 1942, and thereafter the said case arose between the parties,

which by stipulation approved by the court was settled among them in

the following manner: Beginning with the month of September 1944 the

usufructuary shall collect all the rents of the property in question; shall,

at her own cost and expense, pay all the real estate taxes, special

assessments, and insurance premiums, including the documentary

stamps, and make all the necessary repairs on the property; and in case

of default on her part the owner shall the right to do any or all of those

things, in which event he shall be entitled to collect all subsequent rents

until the amounts paid by him are fully satisfied, after which the

usufructuary shall again collect the rents. It was further stipulated by the

parties and decreed by the court that "the foregoing shall be in effect

during the term of the usufruct and shall be binding on the successors

and assigns of each of the parties."

Construing said judgment in the light of the ninth clause of the will of the

deceased Rosario Fabie y Grey, which was quoted in the decision and by

which Josefa Fabie was made by the usufructuary during her lifetime of

the income of the property in question, we find that the said

usufructuary has the right to administer the property in question. All the

acts of administration to collect the rents for herself, and to conserve

the property by making all necessary repairs and paying all the taxes,

special assessments, and insurance premiums thereon were by said

judgment vested in the usufructuary. The pretension of the respondent

Juan Grey that he is the administrator of the property with the right to

choose the tenants and to dictate the conditions of the lease is contrary

to both the letter and the spirit of the said clause of the will, the

stipulation of the parties, and the judgment of the court. He cannot

manage or administer the property after all the acts of management and

administration have been vested by the court, with his consent, in the

usufructuary. He admitted that before said judgment he had been

collecting the rents as agent of the usufructuary under an agreement

with the latter. What legal justification or valid excuse could he have to

claim the right to choose the tenant and fix the amount of the rent when

under the will, the stipulation of the parties, and the final judgment of

the court it is not he but the usufructuary who is entitled to said rents?

As long as the property is properly conserved and insured he can have

no cause for complaint, and his right in that regard is fully protected by

the terms of the stipulation and the judgment of the court above

mentioned. To permit him to arrogate to himself the privilege to choose

the tenant, to dictate the conditions of the lease, and to sue when the

lessee fails to comply therewith, would be to place the usufructuary

entirely at his mercy. It would place her in the absurd situation of having

a certain indisputable right without the power to protect, enforce, and

fully enjoy it.

One more detail needs clarification. In her complaint for desahucio Josefa

Fabie alleges that she needs the premises in question to live in, as her

former residence was burned. Has she the right under the will and the

judgment in question to occupy said premises herself? We think that, as

a corollary to her right to all the rent, to choose the tenant, and to fix the

amount of the rent, she necessarily has the right to choose herself as the

tenant thereof, if she wishes to; and, as she fulfills her obligation to pay

the taxes and insure and conserve the property properly, the owner has

no legitimate cause to complain. As Judge Nable of the municipal court

said in his decision, "the pretension that the plaintiff, being a mere

usufructuary of the rents, cannot occupy the property, is illogical if it be

taken into account that that could not have been the intention of the

testatrix."

We find that upon the pleadings, the undisputed facts, and the law the

action instituted in the municipal court by the petitioner Josefa Fabie

against the respondent Ngo Soo is one of unlawful detainer, within the

original jurisdiction of said court, and that therefore Judges Dizon and

Gutierrez David of the Court of First Instance erred in holding otherwise

and in quashing the case upon appeal.

2. The next question to determine is the propriety of the remedy availed

of by the petitioner in this Court. Judging from the allegations and the

prayer of the petition, it is in the nature of certiorari and mandamus, to

annul the order of dismissal and to require the Court of First Instance to

try and decide the appeal on the merits. Under section 3 of Rule 67,

when any tribunal unlawfully neglects the performance of an act which

the law specifically enjoins as a duty resulting from an office, and there is

no other plain, speedy, and adequate remedy in the ordinary course of

law, it may be compelled by mandamus to do the act required to be done

to protect the rights of the petitioner. If, as we find, the case before the

respondent judge is one of unlawful detainer, the law specifically

requires him to hear and decide that case on the merits, and his refusal

to do so would constitute an unlawful neglect in the performance of that

duty within section 3 of Rule 67. Taking into consideration that the law

requires that an unlawful detainer case be promptly decided (sections 5

and 8, Rule 72),it is evident that an appeal from the order of dismissal

would not be a speedy and adequate remedy; and under the authority

of Cecilio vs. Belmonte (48 Phil., 243, 255), and Aguilar vs. Cabrera and

Flameo (G.R. No. 49129), we hold that mandamus lies in this case.

3. The contention of the petitioner that the appeal of the intervenor Juan

Grey was filed out of time is not well founded. Although said respondent

received copy of the decision of the municipal court on August 3, 1945,

according to the petitioner (on August 6, 1945, according to the said

respondent), it appears from the sworn answer of the respondent Ngo

Soo in this case that on August 8 he filed a motion for reconsideration,

which was granted in part on August 18. Thus, if the judgment was

modified on August 18, the time for the intervenor Juan Grey to appeal

therefrom did not run until he was notified of said judgment as modified,

and since he filed his notice of appeal on August 23, it would appear that

his appeal was filed on time. However, we observe in this connection

that said appeal of the intervenor Juan Grey, who chose not to answer

the petition herein, would be academic in view of the conclusions we

have reached above that the rights between him as owner and Josefa

Fabie as usufructuary of the property in question have been definitely

settled by final judgment in civil case No. 1659 of the Court of First

Instance of Manila in the sense that the usufructuary has the right to

administer and possess the property in question, subject to certain

specified obligations on her part.

The orders of dismissal of the respondent Court of First Instance, dated

September 22 and October 31, 1945, in thedesahucio case (No. 71149)

are set aside that court is directed to try and decide the said case on the

merits; with the costs hereof against the respondent Ngo Soo.

Moran, C.J., Paras, Jaranilla, Feria, De Joya, Pablo, Perfecto, Bengzon, and

Briones, JJ., concur.

[G.R. No. L-28034. February 27, 1971.]

THE BOARD OF ASSESSMENT APPEALS OF ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR

and PLACIDO L. LUMBAY, in his capacity as Provincial Assessor of

Zamboanga del Sur, Petitioners, v. SAMAR MINING COMPANY, INC.

and THE COURT OF TAX APPEALS, Respondents.

Solicitor General Antonio P. Barredo, Assistant Solicitor General

Pacifico P. de Castro and Solicitor Lolita O. Gal-lang, for Petitioners.

Pacifico de Ocampo and Sofronio G. Sayo for respondent Samar

Mining Company, Inc.

D E C I S I O N

ZALDIVAR, J.:

Appeal from the decision of the Court of Tax Appeals, in its CTA Case No.

1705, declaring respondent Samar Mining Company, Inc. (hereinafter

referred to as Samar, for short) exempt from paying the real property

tax assessed against it by the Provincial Assessor of Zamboanga del Sur.

There is no dispute as to the facts of this case. Samar is a domestic

corporation engaged in the mining industry. As the mining claims and

the mill of Samar are located inland and at a great distance from the

loading point or pier site, it decided to construct a gravel road as a

convenient means of hauling its ores from the mine site at Buug to the

pier area at Pamintayan, Zamboanga del Sur; that as an initial step in the

construction of a 42-kilometer road which would traverse public lands

Samar, in 1958 and 1959, filed with the Bureau of Lands and the Bureau

of Forestry miscellaneous lease applications for a road right of way on

lands under the jurisdiction of said bureaus where the proposed road

would traverse; that having been given temporary permit to occupy and

use the lands applied for by it, said respondent constructed a road

thereon, known as the Samico road; that although the gravel road was

finished in 1959, and had since then been used by the respondent in

hauling its iron from its mine site to the pier area, and that its lease

applications were approved on October 7, 1965, the execution of the

corresponding lease contracts were held in abeyance even up to the time

this case was brought to the Court of Tax Appeals. 1

On June 5, 1964, Samar received a letter from the Provincial Assessor of

Zamboanga del Sur assessing the 13.8 kilometer road 2 constructed by it

for real estate tax purposes in the total sum of P1,117,900.00. On July 14,

1964, Samar appealed to the Board of Assessment Appeals of

Zamboanga del Sur, (hereinafter referred to as Board, for short),

contesting the validity of the assessment upon the ground that the road

having been constructed entirely on a public land cannot be considered

an improvement subject to tax within the meaning of section 2 of

Commonwealth Act 470, and invoking further the decision of this Court

in the case of Bislig Bay Lumber Company, Inc. v. The Provincial

Government of Surigao, G.R. No. L-9023, promulgated on November 13,

1956. On February 10, 1965, after the parties had submitted a

stipulation of facts, Samar received a resolution of the Board, dated

December 22, 1964, affirming the validity of the assessment made by the

Provincial Assessor of Zamboanga del Sur under tax declaration No.

3340, but holding in abeyance its enforceability until the lease contracts

were duly executed.

On February 16, 1965, Samar moved to reconsider the resolution of the

Board, praying for the cancellation of tax declaration No. 3340, and on

August 3, 1965, Samar received Resolution No. 13 not only denying its

motion for reconsideration but modifying the Boards previous

resolution of December 22, 1964 declaring the assessment immediately

enforceable, and that the taxes to be paid by Samar should accrue or

commence with the year 1959. When its second motion for

reconsideration was again denied by the Board, Samar elevated the case

to the Court of Tax Appeals.

The jurisdiction of the Court of Tax Appeals to take cognizance of the

case was assailed by herein petitioners (the Board and the Provincial

Assessor of Zamboanga del Sur) due to the failure of Samar to first pay

the realty tax imposed upon it before interposing the appeal, and prayed

that the resolution of the Board appealed from be affirmed. On June 28,

1967, the Court of Tax Appeals ruled that it had jurisdiction to entertain

the appeal and then reversed the resolution of the Board. The Court of

Tax Appeals ruled that since the road is constructed on public lands such

that it is an integral part of the land and not an independent

improvement thereon, and that upon the termination of the lease the

road as an improvement will automatically be owned by the national

government, Samar should be exempt from paying the real estate tax

assessed against it. Dissatisfied with the decision of the Court of Tax

Appeals, petitioners Board and Placido L. Lumbay, as Provincial Assessor

of Zamboanga del Sur, interposed the present petition for review before

this Court.

The issue to be resolved in the present appeal is whether or not

respondent Samar should pay realty tax on the assessed value of the

road it constructed on alienable or disposable public lands that are

leased to it by the government.

Petitioners maintain that the road is an improvement and, therefore,

taxable under Section 2 of the Assessment Law (Commonwealth Act No.

470) which provides as follows:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"Sec. 2. Incidence of real property tax. Except in chartered cities, there

shall be levied, assessed, and collected, an annual, ad valorem tax on real

property including land, buildings, machinery, and other improvements

not hereinafter specifically exempted."cralaw virtua1aw library

There is no question that the road constructed by respondent Samar on

the public lands leased to it by the government is an improvement. But

as to whether the same is taxable under the aforequoted provision of the

Assessment Law, this question has already been answered in the

negative by this Court. In the case of Bislig Bay Lumber Co., Inc. v.

Provincial Government of Surigao, 100 Phil. 303, where a similar issue

was raised as to whether the timber concessionaire should be required

to pay realty tax for the road it constructed at its own expense within the

territory of the lumber concession granted to it, this Court, after citing

Section 2 of Commonwealth Act 470, held:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"Note that said section authorizes the levy of real tax not only on lands,

buildings, or machinery that may be erected thereon, but also on any

other improvements, and considering the road constructed by appellee

on the timber concession granted to it as an improvement, appellant

assessed the tax now in dispute upon the authority of the above

provision of the law.

"It is the theory of appellant that, inasmuch as the road was constructed

by appellee for its own use and benefit it is subject to real tax even if it

was constructed on a public land. On the other hand, it is the theory of

appellee that said road exempt from real tax because (1) the road

belongs to the national government by right of accession, (2) the road

belongs to the be removed or separated from the land on which it is

constructed and so it is part and parcel of the public land, and (3),

according to the evidence, the road was built not only for the use and

benefit of appellee but also of the public in general.

"We are inclined to uphold the theory of appellee. In the first place, it

cannot be disputed that the ownership of the road that was constructed

by appellee belongs to the government by right of accession not only

because it is inherently incorporated or attached to the timber land

leased to appellee but also because upon the expiration of the

concession, said road would ultimately pass to the national government

(Articles 440 and 445, new Civil Code; Tobatabo v. Molero, 22 Phil., 418).

In the second place, while the road was constructed by appellee

primarily for its use and benefit, the privilege is not exclusive, for, under

the lease contract entered into by the appellee and the government, its

use can also be availed of by the employees of the government and by

the public in general. . . . In other words, the government has practically

reserved the rights to use the road to promote its varied activities. Since,

as above shown, the road in question cannot be considered as an

improvement which belongs to appellee, although in part is for its

benefit, it is clear that the same cannot be the subject of assessment

within the meaning of section 2 of Commonwealth Act No. 470.

"We are not oblivious of the fact that the present assessment was made

by appellant on the strength of an opinion rendered by the Secretary of

Justice, but we find that the same is predicated on authorities which are

not in point, for they refer to improvements that belong to the lessees

although constructed on lands belonging to the government. It is well

settled that a real tax, being a burden upon the capital, should be paid by

the owner of the land and not by a usufructuary (Mercado v. Rizal, 67

Phil., 608; Article 597, new Civil Code). Appellee is but a partial

usufructuary of the road in question."cralaw virtua1aw library

Again, in the case of Municipality of Cotabato, Et. Al. v. Santos, Et Al., 105

Phil. 963, this Court ruled that the lessee who introduced improvements

consisting of dikes, gates and guard-houses on swamp lands leased to

him by the Bureau of Fisheries, in converting the swamps into fishponds,

is exempt from payment of realty taxes on those improvements. This

Court held:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"We however believe that the assessment on the improvements

introduced by defendant on the fishpond has included more than what is

authorized by law. The improvements as assessed consist of dikes, gates

and guard-houses and bodegas totals P6,850.00 which appellants are not

now questioning, but they dispute the assessment on the dikes and gates

in this wise: After the swamps were leased to appellants, the latter

cleared the swamps and built dikes, by pushing the soil to form these

dikes in the same way that paddies are built on lands intended for the

cultivation of palay, the only difference being that dikes used in

fishponds are relatively much larger than the dikes used in ricelands.

We believe this contention to be correct, because those dikes can really

be considered as integral parts of the fishponds and not as independent

improvements. They cannot be taxed under the assessment law. The

assessment, therefore, with regard to improvements should be modified

excluding the dikes and gates."cralaw virtua1aw library

It is contended by petitioners that the ruling in the Bislig case is not

applicable in the present case because if the concessionaire in the Bislig

case was exempt from paying the realty tax it was because the road in

that case was constructed on a timberland or on an indisposable public

land, while in the instant case what is being taxed is 13.8 kilometer

portion of the road traversing alienable public lands. This contention has

no merit. The pronouncement in the Bislig case contains no hint

whatsoever that the road was not subject to tax because it was

constructed on inalienable public lands. What is emphasized in the lease

is that the improvement is exempt from taxation because it is an integral

part of the public land on which it is constructed and the improvement is

the property of the government by right of accession. Under Section 3(a)

of the Assessment Law (Com. Act 470), all properties owned by the

government, without any distinction, are exempt from taxation.

It is also contended by petitioners that the Court of Tax Appeals can not

take cognizance of the appeal of Samar from the resolution of the Board

assessing realty tax on the road in question, because Samar had not first

paid under protest the realty tax assessed against it as required under

the provisions of Section 54 of the Assessment Law (Com. Act 470),

which partly reads as follows:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"SEC. 54. Restriction upon power of Court to impeach tax. No court

shall entertain any suit assailing the validity of a tax assessment under

this Act until the taxpayer shall have paid under protest the taxes

assessed against him, no shall any court declare any tax invalid by

reason . . ."cralaw virtua1aw library

The extent and scope of the jurisdiction of the Court of Tax Appeals

regarding matters related to assessment or real property taxes are

provided for in Section 7, paragraph (3) and Section 11 of Republic Act

No. 1125, which partly read as follows:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"SEC. 7. Jurisdiction. The Court of Tax Appeals shall exercise exclusive

appellate jurisdiction to review by appeal, as herein provided

x x x

(3) Decisions of provincial or city Board of Assessment Appeals in cases

involving the assessment and taxation of real property or other matters

arising under the Assessment Law, including rules and regulations

relative thereto."cralaw virtua1aw library

"SEC. 11. Who may appeal; effect of appeal. Any person, association or

corporation adversely affected by a decision or ruling of . . . any

provincial or city Board of Assessment Appeals may file an appeal in the

Court of Tax Appeals within thirty days after the receipt of such decision

or ruling."cralaw virtua1aw library

In this connection the Court of Tax Appeals, in the decision appealed

from, said:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"Prior to the enactment of Republic Act No. 1125, all civil actions

involving the legality of any tax, impost or assessment were under the

jurisdiction of the Court of First Instance (Sec. 44, Republic Act No. 296).

It is clear, therefore, that before the creation of the Court of Tax Appeals

all cases involving the legality of assessments for real property taxes, as

well as the refund thereof, were properly brought and taken cognizance

by the said court. However, with the passage by Congress and the

approval by the President of Republic Act No. 1125, the jurisdiction over

cases involving the validity of realty tax assessment were transferred

from the Court of First Instance to the Court of Tax Appeals (See Sec. 22,

Rep. Act No. 1125). The only exception to the grant of exclusive appellate

jurisdiction to the Tax Court relates to cases involving the refund of real

property taxes which remained with the Court of First Instance (See of

Cabanatuan, Et. Al. v. Gatmaitan, Et Al., G.R. No. L-19129, February 28,

1963).

"A critical and analytical study of Section 7 of Republic Act No. 1125, in

relation to subsections (1), (2) and (3) thereof, will readily show that it

was the intention of Congress to lodge in the Court of Tax Appeals the

exclusive appellate jurisdiction over cases involving the legality of real

property tax assessment. as distinguished from cases involving the

refund of real property taxes. To require the taxpayer, as contended by

respondents, to pay first the disputed real property tax before he can file

an appeal assailing the legality and validity of the realty tax assessment

will render nugatory the appellate jurisdictional power of the Court of

Tax Appeals as envisioned in Section 7 (3), in relation to Section 11, of

Republic Act No. 1125. If we follow the contention of respondents to its

logical conclusion, we cannot conceive of a case involving the legality

and validity of real property tax assessment, decided by the Board of

Assessment Appeals, which can be appealed to the Court of Tax Appeals,

The position taken by respondents is, therefore, in conflict with the

Explanatory Note contained in House Bill No. 175, submitted during the

First Session, Third Congress of the Republic of the Philippines, and the

last paragraph of Section 21 of Republic Act No. 1125 which provide as

follows:chanrob1es virtual 1aw library

SEC. 21. General provisions.

x x x

Any law or part of law, or any executive order, rule or regulation or part

thereof, inconsistent with the provisions of this Act is hereby repealed.

"Accordingly, we hold that this Court can entertain and give due course

to petitioners appeal assailing the legality and validity of the real

property tax assessment here in question without paying first the

disputed real property tax as required by Section 54 of the Assessment

Law."cralaw virtua1aw library

We agree with the foregoing view of the Court of Tax Appeals. It should

be noted that what is involved in the present case is simply an

assessment of realty tax, as fixed by the Provincial Assessor of

Zamboanga del Sur, which was disputed by Samar before the Board of

Assessment Appeals of said province. There was no demand yet for

payment of the realty tax. In fact the letter of Provincial Assessor, of June

5, 1964, notifying Samar of the assessment, states as

follows:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"Should you find the same to be not in accordance with law or its

valuation to be not satisfactory, you may appeal this assessment under

Section 17 of Commonwealth Act 470 to the Board of Assessment

Appeals, through the Municipal Treasurer of Buug, Zamboanga del Sur,

within 60 days from the date of your receipt hereof." 3

Accordingly Samar appealed to the Board questioning the validity of the

assessment. The Board rendered a resolution over-ruling the contention

of Samar that the assessment was illegal. Then Samar availed of its right

to appeal from the decision of the Board to the Court of Tax Appeals as

provided in Section 11 of Republic Act 1125. Section 11 does not require

that before an appeal from the decision of the Board of Assessment

Appeals can be brought to the Court of Tax Appeals it must first be

shown that the party disputing the assessment had paid under protest

the realty tax assessed. In the absence of such a requirement under the

law, all that is necessary for a party aggrieved by the decision of the

Board of Assessment Appeals is to file his notice of appeal to the Court of

Tax Appeals within 30 days after receipt of the decision of the Board of

Assessment Appeals, as provided in Section 11 of Republic Act 1125.

This Court, in the case of City of Cabanatuan v. Gatmaitan, 4

said:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

". . . if the real estate tax has already been paid it is futile for a taxpayer to

take the matter to the City Board of Assessment Appeals for the

jurisdiction of that body is merely confined to the determination of the

reasonableness of the assessment or taxation of the property and is not

extended to the authority of requiring the refund of the tax unlike cases

involving assessment of internal revenue taxes. In the circumstances, we

hold that this case comes under the jurisdiction of the proper court of

first instance it involving the refund of a real estate tax which does not

come under the appellate jurisdiction of the Court of Tax

Appeals."cralaw virtua1aw library

From the aforequoted portion of the decision of this Court, We gather

that the only question that may be brought before the City or Provincial

Board of Assessment Appeals is the question which relates to the

reasonableness or legality of the realty tax that is assessed against a

taxpayer. Such being the case, it would be unjust to require the realty

owner to first pay the tax, that he precisely questions, before he can

lodge an appeal to the Court of Tax Appeals. We believe that it is not the

intendment of the law that in questioning before the Court of Tax

Appeals the validity or reasonableness of the assessment approved by

the Board of Assessment Appeals the taxpayer should first pay the

questioned tax. It is Our view that in so far as appeals from the decision

or resolution of the Board of Assessment Appeals, Section 54 of

Commonwealth Act 470 does not apply, and said section can be

considered as impliedly repealed by Sections 7, 11 and 21 of Republic

Act 1125.

IN VIEW OF THE FOREGOING, the decision of the Court of Tax Appeals,

appealed from, is affirmed, without pronouncement as to costs. It is so

ordered.

G.R. No. L-44428 September 30, 1977

AVELINO BALURAN, petitioner,

vs.

HON. RICARDO Y. NAVARRO, Presiding Judge, Court of First Instance

of Ilocos Norte, Branch I and ANTONIO OBEDENCIO, respondents.

Alipio V. Flores for petitioner.

Rafael B. Ruiz for private respondent.

MUOZ PALMA, J.:

Spouses Domingo Paraiso and Fidela Q. Paraiso were the owners of a

residential lot of around 480 square meters located in Sarrat, Ilocos

Norte. On or about February 2, 1964, the Paraisos executed an

agreement entitled "BARTER" whereby as party of the first part they

agreed to "barter and exchange" with spouses Avelino and Benilda

Baluran their residential lot with the latter's unirrigated riceland

situated in Sarrat, Ilocos Norte, of approximately 223 square meters

without any permanent improvements, under the following conditions:

1. That both the Party of the First Part and the Party of

the Second Part shall enjoy the material possession of

their respective properties; the Party of the First Part

shall reap the fruits of the unirrigated riceland and the

Party of the Second Part shall have a right to build his

own house in the residential lot.

2. Nevertheless, in the event any of the children of

Natividad P. Obencio, daughter of the First Part, shall

choose to reside in this municipality and build his own

house in the residential lot, the Party of the Second Part

shall be obliged to return the lot such children with

damages to be incurred.

3. That neither the Party of the First Part nor the Party of

the Second Part shall encumber, alienate or dispose of in

any manner their respective properties as bartered

without the consent of the other.

4. That inasmuch as the bartered properties are not yet

accordance with Act No. 496 or under the Spanish

Mortgage Law, they finally agreed and covenant that this

deed be registered in the Office of the Register of Deeds

of Ilocos Norte pursuant to the provisions of Act No. 3344

as amended. (p. 28, rollo)

On May 6, 1975 Antonio Obendencio filed with the Court of First

Instance of Ilocos Norte the present complaint to recover the above-

mentioned residential lot from Avelino Baluran claiming that he is the

rightful owner of said residential lot having acquired the same from his

mother, Natividad Paraiso Obedencio, and that he needed the property

for Purposes Of constructing his house thereon inasmuch as he had

taken residence in his native town, Sarrat. Obedencio accordingly prayed

that he be declared owner of the residential lot and that defendant

Baluran be ordered to vacate the same forfeiting his (Obedencio) favor

the improvements defendant Baluran had built in bad faith.

1

Answering the complaint, Avelino Baluran alleged inter alia (1) that the

"barter agreement" transferred to him the ownership of the residential

lot in exchange for the unirrigated riceland conveyed to plaintiff's

Predecessor-in-interest, Natividad Obedencio, who in fact is still in On

thereof, and (2) that the plaintiff's cause of action if any had prescribed.

2

At the pre-trial, the parties agreed to submit the case for decision on the

basis of their stipulation of facts. It was likewise admitted that the

aforementioned residential lot was donated on October 4, 1974 by

Natividad Obedencio to her son Antonio Obedencio, and that since the

execution of the agreement of February 2, 1964 Avelino Baluran was in

possession of the residential lot, paid the taxes of the property, and

constructed a house thereon with an value of P250.00.

3

On November 8,

1975, the trial Judge Ricardo Y. Navarro rendered a decision the

dispositive portion of which reads as follows:

Consequently, the plaintiff is hereby declared owner of

the question, the defendant is hereby ordered to vacate

the same with costs against defendant.

Avelino Baluran to whom We shall refer as petitioner, now seeks a

review of that decision under the following assignment of errors:

I The lower Court erred in holding that the barter

agreement did not transfer ownership of the lot in suit to

the petitioner.

II The lower Court erred in not holding that the right

to re-barter or re- exchange of respondent Antonio

Obedencio had been barred by the statute of limitation.

(p. 14, Ibid.)

The resolution of this appeal revolves on the nature of the undertaking

contract of February 2, 1964 which is entitled "Barter Agreement."

It is a settled rule that to determine the nature of a contract courts are

not bound by the name or title given to it by the contracting

parties.

4

This Court has held that contracts are not what the parties may

see fit to call them but what they really are as determined by the

principles of law.

5

Thus, in the instant case, the use of the, term "barter"

in describing the agreement of February 2, 1964, is not controlling. The

stipulations in said document are clear enough to indicate that there was

no intention at all on the part of the signatories thereto to convey the

ownership of their respective properties; all that was intended, and it

was so provided in the agreement, was to transfer the material

possession thereof. (condition No. 1, see page I of this Decision) In fact,

under condition No. 3 of the agreement, the parties retained the right to

alienate their respective properties which right is an element of

ownership.

With the material ion being the only one transferred, all that the parties

acquired was the right of usufruct which in essence is the right to enjoy

the Property of another.

6

Under the document in question, spouses

Paraiso would harvest the crop of the unirrigated riceland while the

other party, Avelino Baluran, could build a house on the residential lot,

subject, however, to the condition, that when any of the children of

Natividad Paraiso Obedencio, daughter of spouses Paraiso, shall choose

to reside in the municipality and build his house on the residential lot,

Avelino Baluran shall be obliged to return the lot to said children "With

damages to be incurred." (Condition No. 2 of the Agreement) Thus, the

mutual agreement each party enjoying "material possession" of the

other's property was subject to a resolutory condition the happening

of which would terminate the right of possession and use.

A resolutory condition is one which extinguishes rights and obligations

already existing.

7

The right of "material possession" granted in the

agreement of February 2, 1964, ends if and when any of the children of

Natividad Paraiso, Obedencio (daughter of spouses Paraiso, Party of the

First Part) would reside in the municipality and build his house on the

property. Inasmuch as the condition opposed is not dependent solely on

the will of one of the parties to the contract the spouses Paraiso

but is Part dependent on the will of third persons Natividad

Obedencio and any of her children the same is valid.

8

When there is nothing contrary to law, morals, and good customs Or

Public Policy in the stipulations of a contract, the agreement constitutes

the law between the parties and the latter are bound by the terms

thereof.

9

Art. 1306 of the Civil Code states:

Art. 1306. The contracting parties may establish such

stipulations, clauses, terms and conditions as they may

deem convenient, provided they are not contrary to law,

Morals, good customs, public order, or public policy.

Contracts which are the private laws of the contracting

parties, should be fulfilled according to the literal sense

of their stipulations, if their terms are clear and leave no

room for doubt as to the intention of the contracting

parties, for contracts are obligatory, no matter what their

form may be, whenever the essential requisites for their

validity are present. (Philippine American General

Insurance Co., Inc. vs. Mutuc, 61 SCRA 22)

The trial court therefore correctly adjudged that Antonio Obedencio is

entitled to recover the possession of the residential lot Pursuant to the

agreement of February 2, 1964.

Petitioner submits under the second assigned error that the causa, of

action if any of respondent Obedencio had Prescribed after the lapse of

four years from the date of execution of the document of February 2,

1964. It is argued that the remedy of plaintiff, now respondent, Was to

ask for re-barter or re-exchange of the properties subject of the

agreement which could be exercised only within four years from the

date of the contract under Art. 1606 of the Civil Code.

The submission of petitioner is untenable. Art. 1606 of the Civil Code

refers to conventional redemption which petitioner would want to apply

to the present situation. However, as We stated above, the agreement of

the parties of February 2, 1964, is not one of barter, exchange or even

sale with right to repurchase, but is one of or akin the other is the use or

material ion or enjoyment of each other's real property.

Usufruct may be constituted by the parties for any period of time and

under such conditions as they may deem convenient and beneficial

subject to the provisions of the Civil Code, Book II, Title VI

on Usufruct. The manner of terminating or extinguishing the right of

usufruct is primarily determined by the stipulations of the parties which

in this case now before Us is the happening of the event agreed upon.

Necessarily, the plaintiff or respondent Obedencio could not demand for

the recovery of possession of the residential lot in question, not until he

acquired that right from his mother, Natividad Obedencio, and which he

did acquire when his mother donated to him the residential lot on

October 4, 1974. Even if We were to go along with petitioner in his

argument that the fulfillment of the condition cannot be left to an

indefinite, uncertain period, nonetheless, in the case at bar, the

respondent, in whose favor the resolutory condition was constituted,

took immediate steps to terminate the right of petitioner herein to the

use of the lot. Obedencio's present complaint was filed in May of 1975,

barely several months after the property was donated to him.

One last point raised by petitioner is his alleged right to recover

damages under the agreement of February 2, 1964. In the absence of

evidence, considering that the parties agreed to submit the case for

decision on a stipulation of facts, We have no basis for awarding

damages to petitioner.

However, We apply Art. 579 of the Civil Code and hold that petitioner

will not forfeit the improvement he built on the lot but may remove the

same without causing damage to the property.

Art. 579. The usufructuary may make on the property

held in usufruct such useful improvements or expenses

for mere pleasure as he may deem proper, provided he

does not alter its form or substance; but he shall have no

right to be indemnified therefor. He may, however. He

may, however, removed such improvements, should it be

possible to do so without damage to the

property. (Emphasis supplied)

Finally, We cannot close this case without touching on the unirrigated

riceland which admittedly is in the possession of Natividad Obedencio.

In view of our ruling that the "barter agreement" of February 2, 1964,

did not transfer the ownership of the respective properties mentioned

therein, it follows that petitioner Baluran remains the owner of the

unirrigated riceland and is now entitled to its Possession. With the

happening of the resolutory condition provided for in the agreement, the

right of usufruct of the parties is extinguished and each is entitled to a

return of his property. it is true that Natividad Obedencio who is now in

possession of the property and who has been made a party to this case

cannot be ordered in this proceeding to surrender the riceland. But

inasmuch as reciprocal rights and obligations have arisen between the

parties to the so-called "barter agreement", We hold that the parties and

for their successors-in-interest are duty bound to effect a simultaneous

transfer of the respective properties if substance at justice is to be

effected.

WHEREFORE, Judgment is hereby rendered: 1) declaring the petitioner

Avelino Baluran and respondent Antonio Obedencio the respective

owners the unirrigated riceland and residential lot mentioned in the

"Barter Agreement" of February 2, 1964; 2) ordering Avelino Baluran to

vacate the residential lot and removed improvements built by

thereon, provided, however that he shall not be compelled to do so unless

the unirrigated riceland shall five been restored to his possession either

on volition of the party concerned or through judicial proceedings which

he may institute for the purpose.

Without pronouncement as to costs. So Ordered.

G.R. No. 148830. April 13, 2005

NATIONAL HOUSING AUTHORITY, Petitioners,

vs.

COURT OF APPEALS, BULACAN GARDEN CORPORATION and

MANILA SEEDLING BANK FOUNDATION, INC., Respondents.

D E C I S I O N

CARPIO, J.:

The Case

This is a petition for review

1

seeking to set aside the Decision

2

dated 30

March 2001 of the Court of Appeals ("appellate court") in CA-G.R. CV No.

48382, as well as its Resolution dated 25 June 2001 denying the motion

for reconsideration. The appellate court reversed the Decision

3

of

Branch 87 of the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City ("trial court") dated

8 March 1994 in Civil Case No. Q-53464. The trial court dismissed the

complaint for injunction filed by Bulacan Garden Corporation ("BGC")

against the National Housing Authority ("NHA"). BGC wanted to enjoin

the NHA from demolishing BGCs facilities on a lot leased from Manila

Seedling Bank Foundation, Inc. ("MSBF"). MSBF allegedly has

usufructuary rights over the lot leased to BGC.

Antecedent Facts

On 24 October 1968, Proclamation No. 481 issued by then President

Ferdinand Marcos set aside a 120-hectare portion of land in Quezon City

owned by the NHA

4

as reserved property for the site of the National

Government Center ("NGC"). On 19 September 1977, President Marcos

issued Proclamation No. 1670, which removed a seven-hectare portion

from the coverage of the NGC. Proclamation No. 1670 gave MSBF

usufructuary rights over this segregated portion, as follows:

Pursuant to the powers vested in me by the Constitution and the laws of

the Philippines, I, FERDINAND E. MARCOS, President of the Republic of

the Philippines, do hereby exclude from the operation of Proclamation

No. 481, dated October 24, 1968, which established the National

Government Center Site, certain parcels of land embraced therein and

reserving the same for the Manila Seedling Bank Foundation, Inc., for use

in its operation and projects, subject to private rights if any there be,

and to future survey, under the administration of the Foundation.

This parcel of land, which shall embrace 7 hectares, shall be

determined by the future survey based on the technical descriptions

found in Proclamation No. 481, and most particularly on the original

survey of the area, dated July 1910 to June 1911, and on the subdivision

survey dated April 19-25, 1968. (Emphasis added)

MSBF occupied the area granted by Proclamation No. 1670. Over the

years, MSBFs occupancy exceeded the seven-hectare area subject to its

usufructuary rights. By 1987, MSBF occupied approximately 16 hectares.

By then the land occupied by MSBF was bounded by Epifanio de los

Santos Avenue ("EDSA") to the west, Agham Road to the east, Quezon

Avenue to the south and a creek to the north.

On 18 August 1987, MSBF leased a portion of the area it occupied to BGC

and other stallholders. BGC leased the portion facing EDSA, which

occupies 4,590 square meters of the 16-hectare area.

On 11 November 1987, President Corazon Aquino issued Memorandum

Order No. 127 ("MO 127") which revoked the reserved status of "the 50

hectares, more or less, remaining out of the 120 hectares of the NHA

property reserved as site of the National Government Center." MO 127

also authorized the NHA to commercialize the area and to sell it to the

public.

On 15 August 1988, acting on the power granted under MO 127, the NHA

gave BGC ten days to vacate its occupied area. Any structure left behind

after the expiration of the ten-day period will be demolished by NHA.

BGC then filed a complaint for injunction on 21 April 1988 before the

trial court. On 26 May 1988, BGC amended its complaint to include MSBF

as its co-plaintiff.

The Trial Courts Ruling

The trial court agreed with BGC and MSBF that Proclamation No. 1670

gave MSBF the right to conduct the survey, which would establish the

seven-hectare area covered by MSBFs usufructuary rights. However, the

trial court held that MSBF failed to act seasonably on this right to

conduct the survey. The trial court ruled that the previous surveys

conducted by MSBF covered 16 hectares, and were thus inappropriate to

determine the seven-hectare area. The trial court concluded that to

allow MSBF to determine the seven-hectare area now would be grossly

unfair to the grantor of the usufruct.

On 8 March 1994, the trial court dismissed BGCs complaint for

injunction. Thus:

Premises considered, the complaint praying to enjoin the National

Housing Authority from carrying out the demolition of the plaintiffs

structure, improvements and facilities in the premises in question is

hereby DISMISSED, but the suggestion for the Court to rule that

Memorandum Order 127 has repealed Proclamation No. 1670 is

DENIED. No costs.

SO ORDERED.

5

The NHA demolished BGCs facilities soon thereafter.

The Appellate Courts Ruling

Not content with the trial courts ruling, BGC appealed the trial courts

Decision to the appellate court. Initially, the appellate court agreed with

the trial court that Proclamation No. 1670 granted MSBF the right to

determine the location of the seven-hectare area covered by its

usufructuary rights. However, the appellate court ruled that MSBF did in

fact assert this right by conducting two surveys and erecting its main

structures in the area of its choice.

On 30 March 2001, the appellate court reversed the trial courts ruling.

Thus:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the Decision dated March 8, 1994 of

the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City, Branch 87, is hereby REVERSED

and SET ASIDE. The National Housing Authority is enjoined from

demolishing the structures, facilities and improvements of the plaintiff-

appellant Bulacan Garden Corporation at its leased premises located in

Quezon City which premises were covered by Proclamation No. 1670,

during the existence of the contract of lease it (Bulacan Garden) had

entered with the plaintiff-appellant Manila Seedling Bank Foundation,

Inc.

No costs.

SO ORDERED.

6

The NHA filed a motion for reconsideration, which was denied by the

appellate court on 25 June 2001.

Hence, this petition.

The Issues

The following issues are considered by this Court for resolution:

WHETHER THE PETITION IS NOW MOOT BECAUSE OF THE

DEMOLITION OF THE STRUCTURES OF BGC; and

WHETHER THE PREMISES LEASED BY BGC FROM MSBF IS WITHIN THE

SEVEN-HECTARE AREA THAT PROCLAMATION NO. 1670 GRANTED TO

MSBF BY WAY OF USUFRUCT.

The Ruling of the Court

We remand this petition to the trial court for a joint survey to determine

finally the metes and bounds of the seven-hectare area subject to MSBFs

usufructuary rights.

Whether the Petition is Moot because of the

Demolition of BGCs Facilities

BGC claims that the issue is now moot due to NHAs demolition of BGCs

facilities after the trial court dismissed BGCs complaint for injunction.

BGC argues that there is nothing more to enjoin and that there are no

longer any rights left for adjudication.

We disagree.

BGC may have lost interest in this case due to the demolition of its

premises, but its co-plaintiff, MSBF, has not. The issue for resolution has

a direct effect on MSBFs usufructuary rights. There is yet the central

question of the exact location of the seven-hectare area granted by

Proclamation No. 1670 to MSBF. This issue is squarely raised in this

petition. There is a need to settle this issue to forestall future disputes

and to put this 20-year litigation to rest.

On the Location of the Seven-Hectare Area Granted by

Proclamation No. 1670 to MSBF as Usufructuary

Rule 45 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure limits the jurisdiction of this

Court to the review of errors of law.

7

Absent any of the established

grounds for exception,

8

this Court will not disturb findings of fact of

lower courts. Though the matter raised in this petition is factual, it

deserves resolution because the findings of the trial court and the

appellate court conflict on several points.

The entire area bounded by Agham Road to the east, EDSA to the west,

Quezon Avenue to the south and by a creek to the north measures

approximately 16 hectares. Proclamation No. 1670 gave MSBF a usufruct

over only a seven-hectare area. The BGCs leased portion is located along

EDSA.

A usufruct may be constituted for a specified term and under such

conditions as the parties may deem convenient subject to the legal

provisions on usufruct.

9

A usufructuary may lease the object held in

usufruct.

10

Thus, the NHA may not evict BGC if the 4,590 square meter

portion MSBF leased to BGC is within the seven-hectare area held in

usufruct by MSBF. The owner of the property must respect the lease

entered into by the usufructuary so long as the usufruct

exists.

11

However, the NHA has the right to evict BGC if BGC occupied a

portion outside of the seven-hectare area covered by MSBFs

usufructuary rights.

MSBFs survey shows that BGCs stall is within the seven-hectare area.

On the other hand, NHAs survey shows otherwise. The entire

controversy revolves on the question of whose land survey should

prevail.

MSBFs survey plots the location of the seven-hectare portion by starting

its measurement from Quezon Avenue going northward along EDSA up

until the creek, which serves as the northern boundary of the land in

question. Mr. Ben Malto ("Malto"), surveyor for MSBF, based his survey

method on the fact that MSBFs main facilities are located within this

area.

On the other hand, NHAs survey determines the seven-hectare portion

by starting its measurement from Quezon Avenue going towards Agham

Road. Mr. Rogelio Inobaya ("Inobaya"), surveyor for NHA, based his

survey method on the fact that he saw MSBFs gate fronting Agham

Road.

BGC presented the testimony of Mr. Lucito M. Bertol ("Bertol"), General

Manager of MSBF. Bertol presented a map,

12

which detailed the area

presently occupied by MSBF. The map had a yellow-shaded portion,

which was supposed to indicate the seven-hectare area. It was clear

from both the map and Bertols testimony that MSBF knew that it had

occupied an area in excess of the seven-hectare area granted by

Proclamation No. 1670.

13

Upon cross-examination, Bertol admitted that

he personally did not know the exact boundaries of the seven-hectare

area.

14

Bertol also admitted that MSBF prepared the map without

consulting NHA, the owner of the property.

15

BGC also presented the testimony of Malto, a registered forester and the

Assistant Vice-President of Planning, Research and Marketing of MSBF.

Malto testified that he conducted the land survey, which was used to

construct the map presented by Bertol.

16

Bertol clarified that he

authorized two surveys, one in 1984 when he first joined MSBF, and the

other in 1986.

17

In both instances, Mr. Malto testified that he was asked

to survey a total of 16 hectares, not just seven hectares. Malto testified

that he conducted the second survey in 1986 on the instruction of

MSBFs general manager. According to Malto, it was only in the second

survey that he was told to determine the seven-hectare portion. Malto

further clarified that he based the technical descriptions of both surveys

on a previously existing survey of the property.

18

The NHA presented the testimony of Inobaya, a geodetic engineer

employed by the NHA. Inobaya testified that as part of the NHAs Survey

Division, his duties included conducting surveys of properties

administered by the NHA.

19

Inobaya conducted his survey in May 1988 to

determine whether BGC was occupying an area outside the seven-

hectare area MSBF held in usufruct.

20

Inobaya surveyed the area

occupied by MSBF following the same technical descriptions used by

Malto. Inobaya also came to the same conclusion that the area occupied

by MSBF, as indicated by the boundaries in the technical descriptions,

covered a total of 16 hectares. He further testified that the seven-hectare

portion in the map presented by BGC,

21

which was constructed by Malto,

does not tally with the boundaries BGC and MSBF indicated in their

complaint.

Article 565 of the Civil Code states:

ART. 565. The rights and obligations of the usufructuary shall be those

provided in the title constituting the usufruct; in default of such title, or

in case it is deficient, the provisions contained in the two following

Chapters shall be observed.

In the present case, Proclamation No. 1670 is the title constituting the

usufruct. Proclamation No. 1670 categorically states that the seven-

hectare area shall be determined "by future survey under the

administration of the Foundation subject to private rights if there be

any." The appellate court and the trial court agree that MSBF has the

latitude to determine the location of its seven-hectare usufruct portion

within the 16-hectare area. The appellate court and the trial court

disagree, however, whether MSBF seasonably exercised this right.

It is clear that MSBF conducted at least two surveys. Although both

surveys covered a total of 16 hectares, the second survey specifically

indicated a seven-hectare area shaded in yellow. MSBF made the first

survey in 1984 and the second in 1986, way before the present

controversy started. MSBF conducted the two surveys before the lease to

BGC. The trial court ruled that MSBF did not act seasonably in exercising

its right to conduct the survey. Confronted with evidence that MSBF did

in fact conduct two surveys, the trial court dismissed the two surveys as

self-serving. This is clearly an error on the part of the trial court.

Proclamation No. 1670 authorized MSBF to determine the location of the

seven-hectare area. This authority, coupled with the fact that

Proclamation No. 1670 did not state the location of the seven-hectare

area, leaves no room for doubt that Proclamation No. 1670 left it to

MSBF to choose the location of the seven-hectare area under its usufruct.

More evidence supports MSBFs stand on the location of the seven-

hectare area. The main structures of MSBF are found in the area

indicated by MSBFs survey. These structures are the main office, the

three green houses, the warehouse and the composting area. On the

other hand, the NHAs delineation of the seven-hectare area would cover

only the four hardening bays and the display area. It is easy to

distinguish between these two groups of structures. The first group

covers buildings and facilities that MSBF needs for its operations. MSBF

built these structures before the present controversy started. The

second group covers facilities less essential to MSBFs existence. This

distinction is decisive as to which survey should prevail. It is clear that

the MSBF intended to use the yellow-shaded area primarily because it

erected its main structures there.

Inobaya testified that his main consideration in using Agham Road as the

starting point for his survey was the presence of a gate there. The

location of the gate is not a sufficient basis to determine the starting

point. MSBFs right as a usufructuary as granted by Proclamation No.

1670 should rest on something more substantial than where MSBF

chose to place a gate.

To prefer the NHAs survey to MSBFs survey will strip MSBF of most of

its main facilities. Only the main building of MSBF will remain with MSBF

since the main building is near the corner of EDSA and Quezon Avenue.

The rest of MSBFs main facilities will be outside the seven-hectare area.

On the other hand, this Court cannot countenance MSBFs act of

exceeding the seven-hectare portion granted to it by Proclamation No.

1670. A usufruct is not simply about rights and privileges. A

usufructuary has the duty to protect the owners interests. One such

duty is found in Article 601 of the Civil Code which states:

ART. 601. The usufructuary shall be obliged to notify the owner of any

act of a third person, of which he may have knowledge, that may be

prejudicial to the rights of ownership, and he shall be liable should he

not do so, for damages, as if they had been caused through his own fault.

A usufruct gives a right to enjoy the property of another with the

obligation of preserving its form and substance, unless the title

constituting it or the law otherwise provides.

22

This controversy would

not have arisen had MSBF respected the limit of the beneficial use given

to it. MSBFs encroachment of its benefactors property gave birth to the

confusion that attended this case. To put this matter entirely to rest, it is

not enough to remind the NHA to respect MSBFs choice of the location

of its seven-hectare area. MSBF, for its part, must vacate the area that is

not part of its usufruct. MSBFs rights begin and end within the seven-

hectare portion of its usufruct. This Court agrees with the trial court that

MSBF has abused the privilege given it under Proclamation No. 1670.

The direct corollary of enforcing MSBFs rights within the seven-hectare