Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Boardman AnatStampSealsPersPer (1998)

Uploaded by

ruja_popova1178Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Boardman AnatStampSealsPersPer (1998)

Uploaded by

ruja_popova1178Copyright:

Available Formats

British Institute of Persian Studies

Seals and Signs. Anatolian Stamp Seals of the Persian Period Revisited

Author(s): John Boardman

Source: Iran, Vol. 36 (1998), pp. 1-13

Published by: British Institute of Persian Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4299972

Accessed: 22/10/2009 15:36

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=bips.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

British Institute of Persian Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Iran.

http://www.jstor.org

SEALS AND SIGNS.

ANATOLIAN STAMP SEALS OF THE PERSIAN PERIOD REVISITED

ByJohn

Boardman

Oxford

In Iran VIII

(1970)

pp.

19-45

(hereafter

simply

Iran

VIII)

I assembled and discussed a numerous

series of

pyramidal stamp

seals most of which

seemed to be of west Anatolian

origin,

with

mainly

Achaemenid Persian

figure subjects,

but with a num-

ber which in

style

and

subject

related as much to

Lydo-Greek orientalising

work.

Many

of the seals

were

clearly Lydian

in

origin

in the

light

of their

inscriptions. Many

also carried linear devices which

could be

interpreted

as the

personal

mark of their

owners; indeed,

one declared itself "this is the mark

of... ". This article includes an

updating

of the lists

(in

the

Catalogue

at the

end).

I also revert to discus-

sion of them-their

style

and

especially

the linear

marks or devices which, in the

past twenty-five years,

have taken on a far wider

significance, archaeologi-

cally

and

historically.

I

identify

additions to the Iran

VIII lists

by giving

the new items "decimalised" num-

bers (no.00.1, 00.2 etc.). D-numbers refer to

my list

of the linear devices,

repeated

here with additions

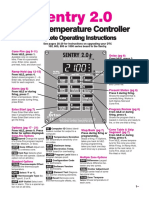

(Fig. 1). Virtually

all the seals are

pyramidal

in

shape

(rectangular

with bevelled corners), have convex

faces and are of

chalcedony (commonly blue). Some

are mounted in silver in a

Lydo-Achaemenid fashion

readily

matched on other silverwork. It seems

probable

that

they begin

in the

early years

of Persian

D1

D1.1 D1.2 D2 D2.1 D3 D4 D5 D6 D7 D8 D9 D9.1

DI0

D11 D12 D13 D14 D15 D16 D17 D18 D19 D19.1

D20 D21 D22 D23 D24 D25 D26 D27 D28 D29 D30

D31 D32 D33 D34 D34.1 D35 D35.1 D35.2 D36 D37 D38

D39 D40 D41 D42 D43 D44 D45 D46 D47 D48 D49

D50

D51.1 D52 D.52.1 D53 D54 D55 D56 D57 D57.1

D58 D59 D60 D61 D62 D63 D64 D64.1 D65

Fig.

1. Linear devices on

pyramidal

and other seals.

1

2

JOURNAL

OF PERSIAN STUDIES

rule in Anatolia

(after

547

B.C.), although

not neces-

sarily

from the

start,

and

may

continue

throughout

the Persian

period although

there is no clear evi-

dence that the seal

type

survived so

long.

The solu-

tion here

depends

on

parallels

with better dated seal-

ings

from

Persia,

but such

parallels

as there are with

Greek seals seem no later than the first half of the

fifth

century.

The non-Greek

scripts

of Anatolia tend

to

cling

to archaic

forms,

but none of the

inscrip-

tions on these seals includes

any

forms that need be

later than archaic. We

depend

much on the other

history

of the linear

devices,

explored

below,

which

yields

at least the

possibility

of an

early

start. 1

Those which seem related to

Lydo-Greek

oriental-

ising

works of the sixth

century present

the

potniai

theron,

some monsters and the lion v. bull

groups,

which are not an

early

motif in Achaemenid arts.2

The

majority

are in what I characterised as an

archaic western form of the Persian Court

Style,

shown at its best in Persian relief

sculpture

and seal-

ings

at

Persepolis

as well as more

generally disposed

on Persian

objects

in various

parts

of the

empire.

It

might

be noted that the lion and bull

foreparts

of

the "Croeseid"

coins,

struck in

Lydia

for Persians

through

most of the second half of the sixth

century,

seem to

carry something

of this

style (which

is ulti-

mately

a

variety

of

Mesopotamian styles

of earlier

years),

as well as much of west Anatolian orientalis-

ing

as seen on the East Greek Wild Goat vases from

the later seventh

century

on. It is a reminder that the

west had

already

been

exposed

to a

long period

of

(As) syrianisation

which had been well

absorbed,

per-

haps

to a

greater degree

than it had been in

Persia,

where Elamite

traditions,

related but

distinct,

were

strong,

as well as eastern

styles

of

non-Mesopotamian

origin (e.g.

the Luristan

bronzes).

From Darius on

the coins attract

figure subjects (the archer)

more

readily

related to

sculptural styles

in the

homeland,

and

displaying

the same

superficial stylistic

elements

derived from the west

(mainly dress).3

Publication and

study

of

sealings

from the

Fortification tablets at

Persepolis,

undertaken

by

Margaret

Cool Root and Mark

Garrison,

extend the

possibilities

of

understanding

the Anatolian

phe-

nomenon. The

sealings

are of 509-494

B.C.,

within

the

reign

of

Darius,

and include

by

500 B.C. an

impression

from one of our seals

carrying

also a

linear device of the standard

variety (no.45.1

with

D2.1), and another, of 495 B.C., explicitly

owned

by

a man from Sardis

carrying

a sealed document of

Artaphernes (no.26.2).4 The western

pyramidals

are

a

Babylonian shape

which continued in use in Persia,

and with

Babylonian devices, apparently

into the

period

of

empire."

Whether or not these had

any

real

currency

in

Lydia (highly improbable),

one can

hardly suppose

that the

Lydo-Persian use of them

was

adopted initially

in the west, rather than carried

from Persia.

But,

stylistically

the

subjects

and

style

in

the initial

stages

seem as much Anatolian as Persian;

thereafter,

as

already

remarked,

keeping

in touch

with Persian taste. The

special

western

usage, notably

with the linear devices, seems not to have been

shared in Persia, where the linear devices are not

conspicuous

on seals

(though they

are in other

media;

see

below).6 Moreover, the east remained

devoted to the

cylinder

for serious

sealing, mainly

ignored

in the west

apart

from some

significantly

notable

exceptions (see below).

The seals used in

Persepolis

for the Fortification

tablets are in various

styles, including

one detected

by

Garrison as a local invention, the "Fortification

Style".7

In

attributing

the western

pyramidal sealing

of 500 B.C.

(no.45.1)

to the

style,

Root raises the

question

whether the whole

phenomenon

starts in

the east

(if so,

with no real

following).

But the

stylis-

tic attribution

might

be

questioned,

and raises

prob-

lems of

dealing

with seal

iconography

and

interpre-

tation,

especially

where

sealings

are involved. The

seal in

question

shows a lion

attacking

a bull, not

quite

in the

pose

usual on the western

pyramidals

since the bull reclines with head back, attacked from

behind,

though

this is common on Greek

seals;8

this

is a

subject

which is well at home in the west, but in

the east

"appears

to be an innovation of Darius' later

years".9

The Fortification

Style

is less

emphatic

and

detailed than the Court

Style,

but in this case it is

possible

to be misled

by sealing impressions

not

driven home

fully

in the

clay,

and with fine-drill

detail

(as

for

paws) clogged by previous

use. The

phenomenon

is familiar to me at least in

dealing

with later

sealings

which are often less

crisp

and

detailed than their related

originals

which can be

cleanly impressed

for

study.

It is also

necessary

to

approach

such

stylistic

matters from the

point

of

view of seal

technique

of miniaturist

proportions,

rather than

straight comparison

with monumental

reliefs. From the

photograph

I think the

published

drawing

can be criticised for

being over-simplified,

and I can see traces of far more

body-marking,

even

drilling (muzzle

and

paw),

which

places

it

securely

with the other

orientalising

westerners,

as do its sub-

ject,

and the

presence

of a

typical

western linear

device.

The

origins

of the western

pyramidals

remain

something

of a

problem.

I

regard

them as a seal

type

introduced from the east but

specially adopted

for

administration in Persian

Lydia,

an area better used

to

stamps

than

cylinders,

and to suitable

intaglio

techniques

and

style (for coins and seals).

Moreover, in

Lydia they

attract

unique

means of

indicating personal ownership

to which we now

turn.

SEALS AND SIGNS. ANATOLIAN STAMP SEALS OF THE PERSIAN PERIOD REVISITED 3

Inscriptions

I listed in Iran VIII ten seals with

Lydian inscrip-

tions

(nos. 1-10).

All were

pyramidal except

the

scaraboid

no.5,

and no.7 which turns out to be a

cylin-

der

(see below).

No.1 declared the device at its centre

to be the mark

(sadmes

= Greek

sema)

of

Mitratas,

a

good

Persian name. Others had

Lydian

names:

Bakivas son of

Sams, Sivams son of

Ates,

and three

(or

four)

times the common Anatolian name Manes. On

three others the names seemed obscure

(nos.8-10).

R.

Gusmani10

observed that I omitted the final m

of the manelim on

no.4,

and adds to those with

Lydian inscriptions my

no.98 which I had taken to be

carrying

an Aramaic

inscription.

This reads

nanas,

a

Lydian

name. He also takes no.7

(mane..omen)

to be

Phrygian,

in which he is

supported by O.

Masson."

Masson,

with Edith Porada's

help,

found where no.7

is

(Buffalo C15046),

which reveals it as a

cylinder.

There are

by

now four additions: two more

pyra-

midal with

Lydian

names

(nos. 10.1,2)

ubnadtolim

(P1.

I, 1)

and milas

(Fig. 2),

the second of which also car-

ries a linear

device,

an inverted version of one

already

known

(D21)

on a

gem

of similar

style (no.33).

There

is also a name on a

cylinder

seal

(no.10.4)

which car-

ries a far more elaborate

figure subject,

as well as a

linear device

(inverted D23 on the

weight stamp

no.189)

in the same

style (Fig. 3).

Its

authenticity

could be in

doubt, however,

there are

epigraphical

problems (it

uses a Greek

pi),

and Gusmani does not

list it. The

name, however,

is

suggestive-pakpuvas.

Poetto thinks it could

easily

be a variant

(or,

I

sup-

pose, simply mis-spelling)

of the known Anatolian

name

Paktyas/es.

If so it

inevitably

calls to mind that

Paktyas

who,

according

to Herodotus

(1, 153-60),

was a

Lydian appointed

to collect revenue from the

Greek cities. His

attempt

at revolt was

suppressed

and

he was

eventually

surrendered to the Persians

by

the

Chians. That this should be our

Paktyas

is

perhaps

too

much to

hope,

and the seal is

possibly

somewhat later

(depending

on when we think the series

started,

but

it is not a

stamp,

after

all,

nor with a usual

subject

and

style). However,

Paktyas'

function was

very

much one

for which

personal identity

on an official seal

(and

a

cylinder,

not a

stamp)

would have been

highly appro-

priate,

indeed

necessary.

Another

pyramidal

seal

(no.10.3)

is now known

(P1.

I, 2),

to add to no.7 as an

example

with what

seems to be a

Phrygian inscription, pserkeyoy

atas. It

may

be noted that all the

Lydian inscriptions

run

rightward

on the seals, leftward in

impression,12

which is the reverse of the

practice

on the two with

Phrygian inscriptions.

Two seals

already

known (nos.13, 15) carry

Cypriot

names and

Greek-style subjects.

These do

not have linear devices (nor do other

Greek-style

pyramidals),

and it seems

unlikely

that

they

are to be

Fig.

2. Borowski Collection.

understood in

quite

the same

light

as the Anatolian.

But there is a scarab, a scaraboid and three metal fin-

ger rings

of Greek

style

with the devices (nos. 194-6,

194.1, 196.1),

all of

probable

Anatolian (or Greek

Cypriot) origin.

Most of the seals with

Lydian or

Phrygian

names seem to have been cut with the

intention of

including

the name and linear device;

other linear devices seem

subsidiary

to the

figure

subjects

but not

necessarily

added on

any

later occa-

sion; I have therefore assumed that

they

were cut the

"right way up" vis-a-vis

the

figure

device.

Subjects

In the

appended supplementary Catalogue

I have

listed additions to the list in Iran VIII,

confining

myself

more

rigorously

to the

pyramidal shape

except

where the

presence

of an obvious linear

device

suggests

inclusion. The

majority

of the sub-

jects

are conventional and within the usual Persian

range, heavily

influenced

by

the

iconography

of

Mesopotamia.

I draw attention here

only

to some

less usual

subjects:

The inscribed

cylinder

no. 10.4

(Fig. 3) carries

one of the most elaborate

subjects, graced

with an

already

known but inverted device (D23). Two

Persians(?)

are seen with a table between them and

the whole ensemble

displays disturbing

features

without

quite being obviously

a

forgery.

Three new

stamps (nos. 17.1, 2, and 3,

possibly 18.3) extend the

range

of

Greek-style

devices with a

satyr (P1.

I, 3), a

sea-monster and a

ploughing

scene. The

satyr

is late

archaic in

type,

and so is the sea-monster

(ketos)

since it is shown as a lion-headed fish, which is the

pre-classical type

that

helps

Thetis in her

struggle

with Peleus in vase

painting, although

then it has no

legs

and the

wings

are

improper.'3

This

may

be a

further hint that the

majority

of these

pyramidals

belong early

in the Persian

period

in the west.

4

JOURNAL

OF PERSIAN STUDIES

Fig.

3. Borowski Collection.

No. 18.1

(P1.

I, 4)

has a

mysterious subject

where a

Greek

(because naked)

disputes

with a Persian over

the smaller

figure

of a

woman,

apparently being

mal-

treated

by

the Greek. This is neither

mythological

nor a usual

protection

motif;

the woman is not

characterised as

Persian,

but is

unlikely

to be

given

Persian

physique

and features

(such

as a

pigtail)

in

glyptic

before the later fifth

century.

I am reluctant

to think that this

may

reflect some local

(Sardian?)

event,

for

instance,

during

the

Ionian

revolt and

attack on Sardis in 499 B.C. No. 190.1

(P1. I, 8),

a

"weight-stamp"

is the most

unusual,

with a

strange

assemblage

of motifs. The woman

holding

a child

and

being

crowned

by

an Eros-like

figure

is not

readily identified,

unless she is some eastern

god-

dess,

heavily graecised.

The siren and bird in the

field seem to have no

function,

and the

dotting

of

part

of the woman's

profile

is

unexplained; perhaps

a veil. There

is,

I

think,

no reason to doubt authen-

ticity.

LinearDevices

The linear devices which

appear

on

many

of the

seals are

by

no means their least

interesting

feature,

and have

important

associations and later

history.

Some

seventy-five

are known

(Fig. 1).

About

twenty

of these take the form

of,

or are

clearly

derived

from,

alphabetic letters,

mainly

Aramaic,

used administra-

tively throughout

the Persian

empire,

but some

might pass

as Greek. There is also a

pseudo-

cartouche

(D65)

and four small devices which seem

to

suggest objects (D51.1,

a

flower; D52,

a

drill;

D52.1,

bow and arrow or

drill; D53).

I shall not dwell

further on these. Most of them

probably

have the

same function as the other devices

(and

some

names)

identifying

individual

owners,

but

they

raise

the

possibility

that the

phenomenon

was not

pecu-

liar to the

Lydian (and

now

Phrygian)

areas within

the western

empire,

which are attested

by

the full

names

given

on some

seals,

but

might

be wider

spread.

Some

appear

on seals and

rings

of

purely

Greek

style, shape

and

subject,

as

already

observed.

The

majority

are

clearly

west Anatolian.

They

are

highly

distinctive,

and

any

met in other contexts are

immediately recognisable. They

do not derive from

the letter forms of Anatolian

scripts,

which were all

devised

by

the sixth

century,

which

might

seem

sur-

prising. Only

the triskeles D64

might

be a

Lydian

let-

ter.

They

have been

deliberately composed

from a

very

narrow

repertory

of

shapes-basically

the circle,

hook,

open

and closed

arc,

short

lines,

some at

angles

or

T-shaped,

some

omegas.

Some are

simply

differently

oriented or stretched versions of the

same device. The

eye easily picks

out the common

features on

Fig.

1. The

composition

is

generally

verti-

cal but a few seem

composed horizontally

and

might

possibly

be intended as

ligatures

of two devices

(D43-46).

As a

group they

are not

any

sort of

alpha-

bet or

syllabary,

a

point

made

equally

well

by

the fact

that

apart

from the

possible ligatures they

are

always

isolated. It

might

well be

thought

that it is

wrong

to

attempt

to detect such a

"family"

of

signs

or to insist

on their common

"syntax",

but

inspection

of

scripts

and

groups

of devices

(usually

of

masons)

of all

periods

and

places

worldwide reveals their coherent

quality, significantly

unlike those devised else-

where.14

I

noted in Iran VIII that their

"syntax" exactly

matched that of the devices seen on Achaemenid

coins of the

fifth/fourth

century,

which are

mainly

a

western and southern Anatolian

phenomenon

(Fig. 4).15

A

closely comparable range

is seen on

silver issues of

subject

states in southern Anatolia of

the fourth

century: Lycia (Fig. 5), Caria,

Pamphylia,

and the countermarks on Athenian coins

circulating

in Persian

Cilicia/Cyprus.16

Two

appear

on

Lycian

tombs,

cut below the

inscriptions

as

though

indicat-

ing

mason or

scribe.17

All are

closely comparable

with the seal devices but have little in common with

the

alphabets

of the same

regions, except

for the

stray sign.

Indeed we

may

well believe that such let-

ters in these

alphabets

as had not been borrowed or

adapted

from Greek or Semitic

scripts

were influ-

enced

by

the

syntax

of the devices we are

studying.'8

Thus,

at the Belevi

quarries

that

supplied

archaic

Ephesus,

the masons' marks are

mainly alphabetic

Fig.

4. Devices on Achaemenid coins.

SEALS AND SIGNS. ANATOLIAN STAMP SEALS OF THE PERSIAN PERIOD REVISITED 5

Fig.

5. Devices on

Lycian

coins.

(broadly Lydo-Carian)

in

character,

but

partly

resembling

our devices.'9 Less formal use of such

marks is not

always easy

to

identify

in

Anatolia,

but

there are several

roughly

similar

graffiti

on

pottery

from Gordion of the sixth to fourth

century (Lydian

period)

.20

The home of the devices seems

clear,

or at least

the area of their

major

use. Their

inspiration

or ori-

gin

is less

easily

determined. There seems

nothing

comparable surviving

in the east which is

pre-

Achaemenid and which can

readily

be taken as

proto-

type.

For

example,

Old Elamite

script comprises

a

variety

of

linear devices,

one or two of which are not

unlike

ours,

but the whole

syntax

is

basically

differ-

ent.21 In Anatolia Hittite and neo-Hittite

hieroglyphs

offer

nothing

to

suggest

direct influence or

inspira-

tion.22 Nor does

any major

class of eastern seal

appear

to

employ

such

devices,

like or unlike ours. In Iran

VIII I

thought

the scheme had been derived from

Greek

practice

with incised or

painted

mercantile

marks on

pottery,

which

go

well back into the Iron

Age;

none of

early date, however, observe the same

principles

of

composition.

In the

early

Iron

Age

the

Greek marks are

usually

no more than

simple

crosses

and I doubt whether

any

are

personal

identifications

rather than a

signal

that a

pot

is

full/empty,

for a

par-

ticular

purpose,

or the like.23

(That they

are not let-

ters is a further indication that the Greeks knew no

alphabet

before the

eighth century.)

From that time

on such marks on Greek vases and other

objects

are

either

simple geometric

forms that

may approximate

to

letters,

or

they

are letters or

monograms.

Some

archaic Rhodian

pottery dipinti (late

seventh-early

sixth

centuries)

offer a few

similarities,

which is hard-

ly surprising (cf.

Iran

VIII,

fig. 5).

The earliest clear

sequence

is Corinthian-all

letters;24

then the

major

Attic series from before the mid-sixth

century

on.

Among

the Athenian

graffiti

a

very

small

group

stands out as

belonging

with our seal devices

(Fig. 6).

They

are all on

figure-decorated

vases

exported

to

Fig. 6.

Merchant marks on Athenian

pottery.

Italy.25

The first

appears

soon after the mid-sixth cen-

tury

and is in use for a

generation,

a

period

in which a

vase-painter

who

signs

himself "the

Lydian"

was work-

ing

in Athens; the rest are late-sixth to

early-fifth

cen-

tury,

and the

thirty

odd known tend to cluster around

particular workshops,

which is a common feature for

such marks.26

They

must indicate the

presence

of

Anatolian merchants

(not necessarily non-Greek) or

others who had

picked up

an Anatolian

practice, but

they

are an extreme

minority among

the merchant

marks on Athenian vases.

Apart

from these, the

Greek connection can now be

ignored.

This

brings

us no closer to

determining

the

origin

of the devices for which, on the seals, the terminus post

quem

must be the establishment of Persian rule in

Anatolia, after 547 B.C.. Their immediate fore-

runners are

probably

to be

sought

on

Lydian

mason-

ry

of the first half of the sixth

century,

before the

Persian invasion. The

dating

is

highly probable-vir-

tually

certain. The marks are carved, often rather

roughly

on ashlar blocks with bold drafted

margins,

a

new

style

of

masonry

for the west,

probably

learnt

from the east and

picked up by Lydians

and Greeks at

about the same time. There is

usually only

one mark

per

block,

at best two. It is more than

likely

that all

are masons' marks, and since their

disposition

on the

walls shows that the marks do not indicate

placing,

it

is

likely

that

they

were

put

on

just

before construc-

tion, in the

quarry, indicating

the work of a mason or

team. Some resemble letters but

they

are, as a

group,

certainly

not a

sample

of the

Lydian alphabet.

Other

explanations

for individual

signs

have been offered: a

monogram gugu

for what was once

thought

the

Tomb of

Gyges,

or

religious/ magic symbols.

But

they

seem to serve the same

purpose

as marks we have

yet

to consider, in Persia, and that most or all indicate

some individual masonic

activity

seems

certain.

The

group

at

Karniyarik Tepe (the

former "Tomb

of

Gyges")

at Sardis is on a monument

confidently

dated to the latest seventh or first half of the sixth cen-

tury, pre-Persian (Fig. 7).27

The first mark, the once-

alleged gugu, appears twenty-five

times in one or an-

other of its forms, once with each on one block. The

other

signs

once each

except

for four swastikas in all.

These are all masons' marks in the

light

of what

appears

elsewhere. At Sardis itself, on a wall at the

north side of the

Acropolis

which is taken to be

pre-

Persian,28

there

are several

pairs

of

angle

marks while

the others

begin

to look more like the seal devices

(Fig. 8). Finally,

on a massive fortification wall in

Sector MMS-N29 there is a

comparable selection

(Fig. 9). Some are

reported

as

being partly erased by

the

cutting

of the block

margins, which was done in

situ. This is a further indication that the marks are ear-

lier than the erection of the wall, probably

from the

quarry.

The

stratigraphy strongly

indicates a

pre-

6

JOURNAL

OF PERSIAN STUDIES

Fig.

7. Masons'marks on

Karmiyarik Tepe,

Sardis.

Fig.

8. Masons' marks on the

Acropolis wall,

Sardis.

Fig.

9. Masons'marks on the MMS-N wall, Sardis.

Persian date. There is a

greater range

of marks

here,

with more

resembling

the seal devices.

Occasionally

marks are

paired

on a block

(always very simple

linear

ones:

Vs,

Xs and an

A)

and most are one to a block.

The

greatest

of the tombs at

Sardis,

confidently

identified as the Tomb of

Alyattes,

who died in

560

B.C.,

has no marks

preserved,

but Herodotus'

description

of it contains an

interesting

comment on

Lydian

interest in the teams involved in such monu-

mental

constructions,

and

although

it

gives

us no

serious information even about the use of masons'

marks,

it does reflect on a

style

of

organisation

in

which

they perhaps played

an

important part.

He

writes

(1, 93): "[The tomb]

was raised

by

the

joint

labours of the tradesmen

(agoraioi),

handicraftsmen

(cheironaktes),

and courtesans of

Sardis,

and had at

the

top

five stone

pillars (ouroi

=

horoi),

which

remained to

my day,

with

inscriptions

cut on

them,

showing

how much of the work was done

by

each

class of work

people.

It

appeared

on measurement

that the

portion

of the courtesans was the

largest."

The last remark was

probably

a tourist

anecdote,

but

there was

perhaps

some such record. The

pillars

are

long gone

and

only

one

large

and one small

globe

marker survived to the nineteenth

century.

One further Sardian monument needs to be men-

tioned,

though

it is

post-547

B.C.

(possibly

not

by

much)

and is of more

potential

interest for its archi-

tectural

relationship

to the

east,

which I shall further

explore

elsewhere. It is the so-called

Pyramid

Tomb.

A recent

study

makes it look less of a

pyramid

but

dates it

probably during

the first

generation

of

Persian

occupation

at

Sardis,

with the

suggestion

that it

may

have been built and

designed locally

for

the burial of a Persian noble. Masons' marks on its

ashlar blocks

comprise

two

swastikas,

and two circles

linked

horizontally,

which are not unlike a

Lydian

letter variant.30

Although

most or all of these marks are not exact-

ly letters,

it will be seen that the

range

is not

quite

that of the seal devices and

overall, fewer use circle

and crescent, which

may

be easier to

manage

with a

drill on a

gem

than with a chisel on a

big

ashlar, but

the

general appearance

is similar and the

apparent

use, to

identify

individual work, is the same. This

conclusion will be reinforced

by

observations in

Persia

(see below). We

may

take it that for the seals

and Anatolian coins a more

sophisticated

series of

devices had to be devised for a number of individu-

als, officials or the like, who wished to mark their

authority

or

ownership

on and with

objects

of some

value. There would have been

many

more such folk

than

quarry

masters, and we must have but a small

proportion

of the total

corpus

of devices. It is cer-

tainly possible

that the new Persian administration

was a

positive

incentive to hasten the evolution of the

practice

for more administrative

purposes, involving

also additions to the formal elements from which the

devices were

composed,

since some seem to recall

sun-discs and their

trappings (D2, 4, 9.1).

If these observations are correct we

may place the

beginning

of the

practice,

so far as the evidence

goes,

in

Lydia,

before the arrival of the Persians, and

assume that their

presence

lent

impetus

to the

prac-

tice for more exalted customers. But the future

history

of the devices remains

long

related to mason-

ry

in a Persian context, as we shall see. This need not

mean that the

concept

was invented in

Lydia and

only

for masons. At best we can

say only

that for the

next two centuries the observable

history

of such

marks is

heavily

Anatolian and Persian, the latter

apparently deriving

from the former.

Any

other

possible

Greek associations need a

moment's discussion, since in Iran VIII I had

thought

that the

practice

was derived from Greece,

and the

subject

has now moved from seals or

pots

to

masonry.

At Old

Smyrna

fine

masonry (without

drafted

margins

and unlike the

Lydian just dis-

cussed)

carries mason marks which seem to be let-

ters,

though

whether

any

of them are

Lydian (or

Carian) rather than Greek is not clear.31 The date is

early sixth-century,

before the destruction

by

SEALS AND SIGNS. ANATOLIAN STAMP SEALS OF THE PERSIAN PERIOD REVISITED 7

Fig.

10. Masons' marks on Tall-i

Takht, Pasargadae.

Alyattes.

Elsewhere on sixth

century

Ionian

architec-

ture

only

letters

appear, nothing

like our

devices;

there is

negative

evidence from

Samos,

Ephesus

and

Miletus.32

So the

Ionian

practice

for masons is as that

for

pot

merchants,

and has

nothing

to do with our

devices. Greek involvement can thus be eliminated

although

the earlier Greek

practice

with other

signs,

discussed

already, might

have been

inspirational,

and earlier

pot

marks in Anatolia offer no

good

precedents,

to

judge

from what has been

published

from

Phrygia.

We turn now to the Persian homeland and have

to do with masons not seals. We know that

Lydian

and

Ionian

masons were

employed by

Darius at

Susa-he tells us as much-and there is

good

archaeological

evidence for their influence and

probable presence

earlier,

under

Cyrus,

at

Pasargadae.33 Many

marks have been recorded on

the

standing

terrace walls of Tall-i

Takht,

the

great

platform overlooking

the

site,

now

fully

studied

by

D. Stronach. Some had been illustrated

compara-

tively recently by

E. Herzfeld

(a

fact unknown to me

when I wrote in Iran

VIII)34

but

they

had also been

observed

by

earlier travellers

(e.g., J. Dieulafoy

in

1821)

who took them to be the

script

of an

unknown

language.

R. Ker Porter took them for

positioning

marks which had

already

been

planned

in the

quarries

where

they

were cut.35 A later

visitor,

E. G.

Browne,

in

1887/8,

mentioned that

they

had

been taken for some ancient

language,

but revealed

that the locals had what we now see to be the

right

answer,

or near it: "The

villager

that

accompanied

me declared that

they

were marks

placed by

each

mason on the stones at which he had

worked,

in

order that the amount of his work and the

wages

due to him

might

be

proved;

and I have no doubt

that such is their nature. At

any

rate

they

in no wise

resemble

any

known

alphabet."36

The

range

of

marks recorded

by

Stronach's team is remarkable

(Fig. 10),17 many closely resembling

the Anatolian

seal devices. A few

appear

also on the core

masonry,

not

just

the facade

ashlars,

and

they

are often

grouped, suggesting

some

quarry organisation

that

can be

imagined

rather than demonstrated. That

they may

also have

something

to do with the

placing

of the blocks

may

be

suggested by

different

group-

ing

north and south,38

which

might equally

reflect

period

of construction and the

operation

of differ-

ent individual masons or teams at different

stages.

Comparable

marks

appear

on blocks at Susa on

the

Apadana (Fig. 11),

built

by

Darius,

and these

include some based on the

circle,39

which are

matched

by

the far more numerous marks on the

Treasury

at

Persepolis (Fig.

12).40

These are on the

top

surfaces of the

many

column bases,

on the

upper

member

(tori)

and the lower

square plinth.41

The

style

of the marks is familiar

by

now,

including

sever-

al

interesting

close

parallels

to those on seals

(e.g.

with

D39).

Most are

singletons,

and similar devices

are

grouped

on bases on the

site,

some in twos and

threes.

They

are on bases of all three

building

periods, mainly

of the

period

of Darius and

early

Xerxes.42 Roaf has collected and

published

the

marks that

appear

on

sculpture

reliefs at

Persepolis,

notably

on the

Apadana

and the Central

Building.43

A distinction can be drawn between these

sculptors'

marks

(Fig.

13),

where individual hands can be

proved by

observation of the

rendering

of

detail,

and

masons' marks,

some of which on

Treasury

bases

match those on the

Apadana,

and

might

indicate

teams as well as individuals, though

where there is a

cluster of marks it seems more

likely

to indicate sev-

eral individuals than several teams.

There

is,

to

my knowledge,

not much more evi-

dence for their use in the

period

of the Achaemenid

empire.

A

single graffito

on a

pot,44

and of a

type

with a

long

later

history, suggests

that the

practice

was not

altogether

confined to stoneworkers,

only

that it is their

usage

that has survived.

Fig.

11.

Masons' marks at Susa.

8

JOURNAL

OF PERSIAN STUDIES

Fig.

12. Masons' marks on the

Treasury, Persepolis.

Fig.

13.

Sculptors'

marks on the

Apadana, Persepolis.

Fig.

14. Masons' marks

from Parthian,

Sasanian and Islamic

buildings, Iran.

Later, however,

the

general concept

of

using

such

devices to

identify

individuals continued

strongly,

and with the same basic

syntax

of construction

though

the

range

of basic

types

becomes more

limited. The

phenomenon

was

investigated by

H.

Janichen

in Bildzeichen der

k6niglichen

Hoheit

bei den

iranischen

Vl1kern

(Bonn, 1956),

but he did not con-

sider their

predecessors.

The

devices,

and others

which

very clearly belong

in the same

tradition,

are

recorded on

Parthian, Sasanian and Islamic build-

ings

in Persia.

Many

have been illustrated more

recently,

and I select some whose

ancestry

is un-

mistakable

(Fig. 14).45

Comparable devices,

in vari-

ous

forms,

served as the mark of

kings

on Parthian

coins

(Jinichen, pl.

26

top)

and for individuals on

Sasanian seals

(ibid.,

pl. 23)

and on the

royal

crowns

(ibid.,

pl. 24).

The seal devices are

mainly

based on

crescents and

horns,

and

may

be in their

way

mono-

grams.46

Farther east

comparable

devices

appear

on

the Kushan coins of north

India, much influenced in

other

ways by

Persian

example (ibid.,

pl. 27);

these

are based

mainly

on

triple (Buddhist)

or

quadruple

fork-motifs,

one of the more

persistent

forms surviv-

ing

from

Lydian

D49

through

Persian.

Seljuks

and

the Golden Horde are not

exempt (ibid.,

pl. 28).

To the

north,

the Sarmatians use what are called

tamgas

for a similar

purpose

and these are

similarly

composed (Fig. 15).47 They are prolific on the north

Black Sea sites and I illustrate one of the stone lions

from Olbia which has been generously decorated

with them

(Fig. 16). The whole practice is naturally

applied also to horse branding in this area and the

whole

phenomenon has been thought to derive

from brands. It is not

impossible that there

was

such an origin since such simple demonstration

of

Fig. 15. Sarmatian tamgas.

Fig. 16. Marble lion from Olbia.

SEALS AND SIGNS. ANATOLIAN STAMP SEALS OF THE PERSIAN PERIOD REVISITED 9

Fig.

17. Brahmi

inscription ofAshoka.

Fig.

18. South Arabian

script.

personal possession

must lie behind the

usage,

but if

it has to do with

branding

it is lost to us because for

the

early period

evidence from

representations

is

lacking.

It would have been an

essentially

Asian

phe-

nomenon,

and its

appearance

first on

masonry

in

Lydia

is at best a little odd.48 There would be

good

reason for

quarrymen

and masons to mark their

work in

any period,

and the

practice

since

antiquity

is common. It is

perhaps surprising

that the marks

do not

appear regularly

on metalwork or other

objets

d'art. It

suggests

that

they

are not so much

sig-

natures as for

purely

administrative

identification,

which

applies

even to those marks which

identify

the

individual

sculptors

on the

Apadana

at

Persepolis;

they

are

by

no means

advertising

their skills rather

than

justifying

their contracts. Sulimirski observed

that similar marks

persisted

for Polish

heraldry

of

the eleventh to

eighteenth

centuries. No doubt the

tradition can be traced further in time and

space by

others familiar with the

evidence;

it survived to

recent times

in some eastern

areas,

to account for

the observations of the locals at

Pasargadae

to

Browne

(see above). Thus,

a

study

of traditional

crafts in Persia remarks how "the craftsman chisels

his stone-mason's mark into each stone. This is a

spe-

cial

sign

that he has chosen at the end of his

appren-

ticeship

and that he uses for the rest of his

life".49

We have come far from the

repertory

of the

Lydian

masons and seal

engravers,

but I think the

succession of the

general concept

of creation and

practice

is clear

though

it

obviously requires

more

refinement for the later

periods

and

places

than can

be

attempted

here. I

repeat

that its

unity

is best

demonstrated

by contrasting

the series with the

way

in which

alphabetic

and similar

scripts

or

groups

of

signs

have been

composed

in other

periods

and

places. Throughout,

the

usage

in our series has

been

non-alphabetic

and there is no

suspicion that

it is

peculiar

to

any particular language.

However,

we

might

have

expected

that such a

simple

formula

for the creation of distinctive devices

might

have

recommended itself to

anyone devising

a

script.

I

think it is

just possible

that this can be detected in

the

early development

of

scripts, especially lapidary

versions of

scripts,

for two

languages, probably with-

in the

period

of the Achaemenid

empire,

which fell

within the interests, albeit

peripheral,

of the Persian

court. Both derive

ultimately

from Aramaic, the

administrative

script

of the

empire,

but the

lapidary

form in which the

scripts

can be

presented, especial-

ly

where there are

ligatures

or

monograms,

bears a

strong

resemblance to the marks discussed above.

The two

scripts

are Brahmi, as we see it best on the

columns inscribed for

King

Ashoka in the third cen-

tury

B.C., and with the full

array

of diacritical marks

(as Fig. 17);5o

and South Arabian

(Fig. 18).51 All that

can be said is that there are

suggestive

similarities in

the

composition

of

many

of the characters and of

their overall

appearance.

One cannot

say more, and

some

might

think that I have

already suggested

too

much.

Fig.

19. Gold

ring

and lion. Borowski collection.

10

JOURNAL

OF PERSIAN STUDIES

CA TALOGUE

The

following

are addenda to Iran VIII that have come

to

my notice,

but with no

attempt

to

update

the biblio-

graphy

of the

original list,

many pieces

in which have since

appeared

in museum

catalogues.

Inscribed

10.1

(P1.

I, 1) London, Malcolm

Hay. Chalcedony.

Two

rearing

lions, heads turned

back,

a tree between. Inscribed

ubnadtolim

(retr.

in

impression).

10.2

(Fig. 2)

Borowski Coll. Blue

chalcedony,

with

gold

cap

and

ring.

Two

rearing goats,

head turned back.

Between them D21

(inverted).

Inscribed in

exergue

with

last letter in field milas. M. Poetto and S.

Salvatori,

La

collezione

anatolica di E. Borowski

(1981),

no.

39,

pl.

39

(the

inscribed "seal" no. 38 is

really

an

amulet).

R.

Gusmani,

Lydisches Worterbuch

Erginzungsheft

III (1986),

no. 106.

Since the middle letter has

equal legs

like a Greek

lambda,

it could

equally

be read as Greek.

10.3

(P1.

I, 2)

Borowski Coll. Blue

chalcedony. Crouching

lion. The

style

is neither Achaemenid nor Greek. D1.1 in

the field and inscribed in

Phrygian pserkeyoy

atas. R.

Gusmani

and M.

Poetto, Kadmos 20

(1981), pp.

64-7 "valeat Atas"?

10.4

(Fig. 3)

Borowski Coll.

Grey chalcedony cylinder.

Beneath a

winged

sun disc of Achaemenid

type

is

enthroned a man

wearing

what looks like a combination of

the Persian

spiked crown,

as it

appears

on

seals,

and the

rounded Median hat. He holds three sticks which in other

circumstances

might

be taken for a barsom. A Mede

(?)

faces him

proffering

a small

cup

on

finger tips,

with a sub-

missive

gesture.

Between them is an

animal-legged

table

bearing

a calf's

head,

a stemmed

cup (?)

and a

loaf(?).

Before the Mede the linear device D23

(inverted)

and

behind him the vertical

inscription pakpuvas (?=

Paktyas/es;

retr. in

impression).

The initial letter is as a

Greek

pi

rather than the usual

Lydian.

The unusual but

not

implausible

elements in the scene

perhaps

tell in

favour of its

authenticity

which

might

otherwise be doubt-

ed. Poetto and

Salvatori,

op.

cit.,

no. 40.

Greek

Style

17.1

(P1.

I, 3)

Basel market. Blue

chalcedony

in silver

mount. A

satyr (hooved)

runs

holding

a

cup.

17.2.

Switzerland, Private. Blue

chalcedony.

Sea monster

(lion

head and

neck,

equine forelegs, wings, long fishy

tail),

over a

dolphin.

17.3 Unknown. A man

driving an

ox-plough over

ground

line as on no. 122.

Orientalising

18.1 (P1. I, 4) Basel market.

Chalcedony.

Beneath a

winged

sun disc a naked male with raised club holds

by the hair a

small woman who

supplicates a

facing Persian. He holds a

dagger

and seizes the naked male

by

his hair. RA 1976, 48,

fig.

7.

18.2 Zurich market. White

chalcedony.

A Mede holds a

branch over a seated Mede

holding

a

cup. Sternberg,

Auktion 11 (1981), pl. 59, no. 1072.

18.3

Sealing

on a

Persepolis

Fortification tablet, PFS 1309s.

Possibly

even "Greek

Style".

A seated man

being

attacked

by

a lion; a snake (?) in the field. Root (see n. 4), fig.

6, pl. 8.

19.1 Basel market. Blue

chalcedony. Winged goddess

holds two lions inverted. Miinzen und Medaillen Liste 450,

no. 415.

19.2 Borowski Coll.

Winged goddess

holds two lions. D34.1

in the field. Poetto and Salvatori, no. 42.

26.2

Sealing

on a

Persepolis

Fortification tablet, PFS1321s.

495 B.C. The tablet is of Dauma, travelling

from Sardis to

Persepolis

with a sealed document from

Artaphernes.

Winged

Mede holds two lions inverted; cross-hatched

exergue.

Root (see n. 4), fig.

5,

pl.

7.

31.1 New York, Rosen 58.

Yellow/grey agate. Walking

lion.

31.2 Zurich, market. Rock

crystal. Walking

lion.

Sternberg,

Auktion 26 (1992), no. 519.

32.1 Moscow, Pushkin. Blue

chalcedony. A winged horse

walking; long tail (not Persian type).

33.1

(P1. I, 6) New York, Rosen 57. Blue

chalcedony with

silver mount from Asia Minor. Two

rampant

lions;

between them D9.1

33.2 Zurich market. White

chalcedony.

Two

rampant

lions.

Sternberg,

Auktion 11

(1981), pl.

59, no. 1074.

33.3

(once 4)

Basel market. Rock

crystal.

Two

rampant

lions with heads turned back. Miinzen und

Medaille;n

Auktion 40

(1969), pl.

1.2.

34.1 Basel market. Blue

chalcedony.

Two

rampant

lions

with heads turned back, a tree between them. Miinzen und

Medaillen Liste

450, no. 416.

34.2

(P1. I, 5)

Malibu 81.AN.76.86.

Chalcedony.

Two ram-

pant

lions with heads turned back, a tree-standard between

them. D64.1 in the field.

J. Spier,

Ancient Gems and

Finger

Rings (Malibu, 1992), pl.

57, no. 109.

43.1 Izmir 3353, from Old

Smyrna. Chalcedony

in silver

mount. Lion attacks bull, bird on

rump. "Aramaic(?) sign

in front of the bull." The Anatolian Civilisation II (Istanbul,

1983), 69, B156.

43.2 New York,

Morgan

Coll. Blue

chalcedony.

Lion

attacks bull. W. H. Ward,

Cylinders.. J.

P.

Morgan (New

York, 1909), pl.

38, 308.

43.3 Basel market. Red banded

agate.

Lion attacks bull.

Miinzen und Medaillen Liste 379, no. 42.

43.4 Borowski Coll. Lion attacks bull. D52.1 in the field.

Poetto and Salvatori, no. 41.

45.1

Sealing on a

Persepolis

Fortification tablet, PFS 1532s.

500 B.C.. Lion attacks bull, flying bird, D2.1 behind; cross-

hatched

exergue. Root (see n. 4), fig. 2,

pl.

4.

55.1

Cyrene.

Rock

crystal.

Lion attacks

goat.

The Extra-

mural

Sanctuary of

Demeter and

Persephone at Cyrene III

(Philadelphia, 1987), no. 30,

pl.

11.

SEALS AND SIGNS. ANATOLIAN STAMP SEALS OF THE PERSIAN PERIOD REVISITED 11

59.1 Basel market. Mottled

yellowish quartz. Dog

attacks

deer.

60.1

(P1.

I, 7)

Basel market. A bird attacks a

running

deer.

Miinzen und Medaillen Liste

379,

no. 43.

66.1

Bonn, Muiller Coll.

Chalcedony.

Griffin

(Greek)

and

fawn. RA

1976, 46,

fig.

2.

71.1

"Heidelberg".

Red

jasper.

Three-bodied deer with

one facing

head. RA

1976,

p.

48,

fig.

6.

Court

Style

76.1 New

York, Rosen 79. Blue

chalcedony.

Mede

fights

lion.

83.1

Moscow, Pushkin.

Grey chalcedony.

Persian

fights

lion.

I.

M.

Nikulina, Iskusstvo

Jonii

i

Achemenidskogo

Irana

(1994), pl.

444.

83.2 Zurich market.

Chalcedony.

Persian

fights

lion.

Sternberg,

Auktion 11

(1981), pls.

59, 63,

no. 1073.

83.3 New

York,

Rosen

144,

from

Turkey.

Obsidian. Persian

fights

lion.

83.4 New York 93.17.53. Blue

chalcedony.

Persian

fights

lion.

D.

Schmandt-Bessarat,

Ancient Persia

(Malibu, 1980),

no. 39.

83.5

Paris, Cab.Med., Chandon de Briailles.

Grey

lime-

stone in silver

mount,

with

palmettes.

Persian

fights

lion.

83.6 Zurich market.

Grey chalcedony.

Persian

fights

lion.

Sternberg,

Auktion 27

(1994),

no. 689.

92.1 Private,

from

Turkey.

Blue

chalcedony.

Persian

fights

lion

griffin.

Erasure

above;

between them D57.1

92.2 New

York, Rosen 141. Blue

chalcedony.

Persian

fights

lion

griffin.

106.1

London, WA,

the

Layard

necklace. Blue

chalcedony.

Persian holds two lions inverted.

Archaeology

in the Levant

(Essays

for K.

Kenyon, Warminster, 1978), p.

174,

no. 17.

106.2 New

York, Rosen 89.

Grey chalcedony.

Persian holds

two lions inverted.

106.3 Borowski Coll. Blue

chalcedony.

Persian holds two

lions inverted.

Above, D1.2. Poetto and

Salvatori,

no. 43.

110.1 Bollmann Coll.

Chalcedony (cut).

Persian holds two

goat sphinxes.

110.1

Moscow, Pushkin. Blue

chalcedony.

A Persian holds

two

goats. I.

M.

Nikulina,

Iskusstvo

Ionii i

Achemenidskogo

Irana

(Moscow, 1994), pl.

443.

111.1 Mtskheta (Georgia) from a second-century A.D.

tomb.

Chalcedony.

A

winged

Persian holds two lions

inverted. The two characters above seem neither like the

usual devices nor an

inscription (? chi-lambda). Antiquaries

Journal

74 (1994), pp. 50-1, no. 53; Antike

Welt 26 (1995),

p. 191, fig.

13.

116.1 Encino market. Blue

chalcedony. Royal sphinx. Joel

L.Malter, Auction 38 (1988), no. 185.

118.1 New York, Rosen 55. Blue

chalcedony.

Two

sejant

royal sphinxes;

D64.1 between them.

121.1 Moscow,

Pushkin. Red

jasper.

A

royal sphinx walking.

123.1 Bonn, Mfiller Coll.

Grey/white chalcedony.

Two

horned winged lions seated, heads turned back.

123.2 Istanbul

(once

New

York).

From

Ugak. Carnelian,

squarish

face,

on twisted

gold loop.

Two horned

winged

lions seated,

facing. Heritage

Recovered. The

Lydian

Treasure

(eds. I.

Ozgen andJ.

Oztiirk, Ankara, 1996),

no. 95.

129.1 New

York,

Rosen 78. Blue

chalcedony.

A

goat-sphinx

walking.

Miinzen

und Medaillen Liste

(Basel), 450, no. 417.

129.2 Vandoeuvres,

Ortiz Coll. Blue

chalcedony. Standing

goat-sphinx

with

paw

raised behind a

leaping

hare.

133.1 New

York,

Rosen 145. Rock

crystal.

Seated

goat-

sphinx

with

forepaw

raised.

133.2 Bonn,

Mfiller Coll. Blue

chalcedony.

Seated

goat-

sphinx.

133.3

Budapest, Academy. "Serpentine".

Seated

goat-

sphinx.

M.

Gramatopol,

Les

pierres gravies

du Cabinet numis-

matique

de

l'Acadimie

Roumaine

(Brussels, 1974), pl.

1,

no.

16.

144.1 Bollmann Coll. Lion

griffin

within border of lotus

and bud. RA

1976,

p.

48,

fig.

5.

Other

Shapes

185. Delete;

Dr Pinkworth

points

out to me that the mark

(D51)

is a South Arabian

monogram.

Cf.

J.

Pirenne,

La

Grice

et Saba

(Paris, 1955), pl.

5b.

190.1

(P1.

I, 8) Jerusalem,

Bible Lands Museum. Blue chal-

cedony weight stamp.

A woman

holding

a

child,

crowned

by

a

winged

male,

accompanied by

a siren and a bird. In

the field D20.

J.

Boardman in Ladders to Heaven

(ed.

O.

W.

Muscarella, Toronto, 1981), p.

168,

no. 141.

190.2 New

York,

Rosen 100. Cornelian

weight stamp

with

part

of bronze mount. Seated

royal sphinx

with head

turned back; before it D35.1.

194.1

(P1. I, 9) Toronto, Hindley

Coll. White chalcedony

scaraboid. Sow. D51.1 over its back.

194.2 Istanbul

(once

New

York)

from

Ugak.

Carnelian

scaraboid

in

gold

swivel

hoop.

Seated

royal sphinx,

with

D20. Archeo 120 (1995), 62; Heritage

Recovered. The

Lydian

treasure

(eds. I.

Ozgen andJ.

Oztfirk

1996),

no. 97.

195.1 (P1. I, 10) Paris,

Cab.

Med.,

Chandon de Briailles.

Carnelian scarab. Two horned

winged

lions,

seated.

Between them D19.1

196.1

(Fig. 19)

Borowski Coll. Gold

ring

with

slim

leaf-

shaped

bezel, thin

hoop.

A lion. D35.2 on its

body.

Poetto

and Salvatori, no. 46.

198.1

Jerusalem,

Bible Lands Museum. Blue

chalcedony

cylinder.

Mare and suckling

foal under a

winged

sun disc.

Hawk over a chick. In the field

D5. Boardman, op.

cit.

(no.190.1), p. 210, no. 173.

198.2 Malibu, J.

Paul

Getty

Museum.

Blue-grey chalcedony

cylinder.

Persian holds two

lions; winged

disc above.

Sign

like D3 inverted.

J. Boardman, Intaglios

and

Rings

(London, 1975), no. 85.

12

JOURNAL

OF PERSIAN STUDIES

1

I am indebted to Professor Michael Roaf for comment and ref-

erences to material relevant for this

article, and to Dr

Roger

Moorey

for his comments on an

early

draft. I am also

grateful

for various comments and assistance from Maria

Brosius,

Margaret

Cool

Root, Sinclair

Hood,

Jeffrey Spier,

and the

cooperation

of various museum curators and collectors

named.

2

D.

Stronach,

"Early

Achaemenid

Coinages",

IA XXIV

(1989),

p.

263.

3

For the

coins, Stronach,

op. cit.,

pp. 255-79, Croeseids on

pl.

1.1-2. For the status of the Court

style,

also

J. Boardman,

Greek Gems and

Finger Rings (London, 1970), p. 305; it is

being

more

fully

studied

by

Mark Garrison.

4 M. C.

Root, "Pyramidal Stamp Sealings-the Persepolis

Connection",

in Persian Studies

(Mem. Volume ... D. M.

Lewis;

ed. A. Kuhrt and M.

Brosius, Oxford, 1998). I am much indebt-

ed to Maria Brosius and Professor Root for

allowing

me access

to her text before

publication.

The two

sealings

are PFS 1532s

(fig. 2,

pl. 4; see also eadem and M.

Garrison,

Persepolis

Seal

Studies

(Leiden, 1996), p.

4,

fig, 1)

and PFS 1321s

(fig.

5,

pl. 7)

=

my

nos.

45.1, 26.2. Others

published by

Root could

belong

here, but I have included

only my

no. 18.3

(which

she takes to

be western too and

might

even be "Greek

Style"),

since it is not

altogether

clear whether the other four

non-Babylonian pyra-

midal

stamps

she

publishes

are

locally

made or from other

areas of the

empire.

Much

depends

on

analysis

of the so-called

Fortification

Style (see below)

which is better demonstrated on

cylinder sealings.

Darius'

brother,

Artaphernes,

was

governor

of Sardis in these

years (Herodotus 5, 25, et

alibi; cf. D. M.

Lewis,

Sparta

and Persia

(Leiden, 1977), p. 2, no.

2).

5

Root,

op.

cit., 36-7.

6

Root, op. cit., 41 remarks that the linear device on PFS1532s

(D2.1)

is

"quite

unlike"

any

of the devices I

listed; but this is

irrelevant since it is

clearly composed according

to the same

syntax,

or as she

puts

it, is "in the

family".

The bisected circle on

PFS1463s

(her fig.

7,

pl. 9)

is

probably

not of the same class at

all, nor in

any way

a

personal

device rather than some other

symbol.

With this

syntax

of

composing

the devices

(on

which

more, below)

exact matches are

very rare, indeed would be

undesirable on most

personal

seals of a

single

context and

close

date, unless an owner had more than one.

7

M.

Garrison, "Seals and the Elite at

Persepolis",

Ars

Orientalis

21

(1991), pp. 1-29,

esp.

10-12.

8 For the Greek see

J. Boardman, Archaic Greek Gems

(London,

1968), p. 123, Scheme

A; the other

pyramidals prefer

Scheme C.

9 See n. 2.

10

"Lydische Siegelaufschriften

und Verbum

Substantivum",

Kadmos 11

(1972), pp.

47-54.

11

"Le sceau

palho-phrygien

de

Mane", Kadmos 26

(1987),

pp.

109-12.

12

Pace R.

Gusmani, Lydisches W6rterbuch

Ergdinzungsheft

I

(Heidelberg, 1980), p.

18. No. 9 is known

only

from a

drawing

which,

I

suspect,

was made from the stone not the

impression

(despite my caption

in Iran

VIII,

fig. 2).

13 LIMCVIII, s.v. "Ketos"

p.

732.

14 See D.

Diringer,

The

Alphabet (London, 1968).

In C. W.

King's

The Gnostics and their Remains

(London, 1864) Plate

O

is of

"Hindoo

Symbols and Caste-Marks", each set

being

in its

way

coherent, and, significantly, the only set that resembles ours is

from the "old Palace of Sadilat" near Isfahan.

15 Iran VIII, fig.

4 and no. 20.

16

See Iran VIII, 25, fig. 5 and references in nn. 20-22.

Examples

for

my Fig. 5 from

Lycia are taken from O. Morkholm and

J. Zahle, "The

Coinages of the

Lycian Dynasts", Acta

Archaeologica 47 (1976), p. 63, fig. 6 and the Index to SNG

Sammlung von Aulock (1981), p. 179. For

Pamphylia, see

S. Atlan, "Die Miinzen der Stadt Side mit sidetischen

Aufschriften", Kadmos

7

(1968), p. 72-they appear singly,

in

pairs or threesomes; for Cilicia, E. T. Newell, "A Cilician Find",

Numismatic Chronicle 1914, p. 5.

17 The last two in the Lycian shown in Fig. 5, also from Morkholm

and Zahle,

op. cit.

18 For

Lycian

and Carian

scripts

see

O.

Masson, "Anatolian

Languages",

in CAH III.2, ch. 34b; for Pamphylian, C. Brixhe,

"L'alphabet epichorique

de Side", Kadmos 8 (1969), pp. 54-84.

19 W. Dressler, "Karoide Inschriften im Steinbruch von Belevi",

Jahreshefte

des Osterreichisches Archdologischen Instituts in Wien 48

(1966/7), pp.

73-6.

20 L. E. Roller, Nonverbal

graffiti, dipinti and stamps (Gordion

Special

Studies 1, 1987), pp. 12-13; her Chart B gives compar-

isons with various other Anatolian

non-alphabetic signs of the

type

we have discussed, but the Gordion examples are very

rough

and mixed with a variety of linear patterns which might

not be

identifying

marks at all.

21 W. Hinz, Altiranische Funde und Forschungen (Berlin, 1969),

p.

44. Cf. Borbu also in the third millennium, D. T. Potts, "The

Potter's Marks of

Tepe Yahya",

Paleorient 7/1 (1981),

pp. 107-22, including

lists of marks from the Indo-Iranian bor-

derlands, Central Asia and India. I am indebted to Professor

Potts (Melbourne) for the reference.

22 For

stamped

and incised devices on

pottery,

U. Seidl,

Boghazk6y-Hattusa

VIII (1972); and

early Syrian, R. Kolinski,

"Early Dynastic

Potter's Marks from Polish Excavations in

Northern

Syria", Berytus

41 (1993/4), pp.

4-27. An abortive

fourteenth/thirteenth-century Byblite syllabary, mainly

derived from

Egyptian hieroglyphs, has a few similar signs:

M. S. Drower,

"Syria,

1550-1400 B.C.", in CAHII.1, 517; Plates

to Vols.

I/IIpl.

103a;

III.1,

794; as do some proto-Sinaitic, ibid.,

799-802. In

Egypt

from the fifth

Dynasty on some

masons'

marks are found, and include circular elements, not on the

whole natural to