Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Applicant's Record (September 30, 2014)

Uploaded by

Air Passenger RightsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Applicant's Record (September 30, 2014)

Uploaded by

Air Passenger RightsCopyright:

Available Formats

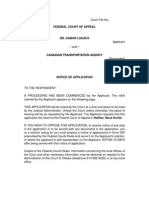

Court File No.

: A-218-14

FEDERAL COURT OF APPEAL

BETWEEN:

DR. GBOR LUKCS

Applicant

and

CANADIAN TRANSPORTATION AGENCY

Respondent

(Application under section 28 of the Federal Courts Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. F-7)

APPLICANTS RECORD

VOLUME 1

Dated: September 30, 2014

DR. GBOR LUKCS

Halifax, NS

lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca

Applicant

TO: CANADIAN TRANSPORTATION AGENCY

15 Eddy Street

Gatineau, QC J8X 4B3

Odette Lalumire

Tel: (819) 994 2226

Fax: (819) 953 9269

Solicitor for the Respondent,

Canadian Transportation Agency

TABLE OF CONTENTS OF VOLUME 1

1 Notice of Application 1

2 Afdavit of Dr. Gbor Lukcs, afrmed on April 25, 2014 13

A Email of Dr. Lukcs to the Agency,

dated February 14, 2014 18

B Follow-up email of Dr. Lukcs to the Agency,

dated February 17, 2014 20

C Email of Ms. Odette Lalumiere, Senior Counsel of

the Agency, to Dr. Lukcs, dated February 17, 2014 22

D Follow-up email of Dr. Lukcs to the Agency,

dated February 21, 2014 24

E Email of Ms. Lalumiere to Dr. Lukcs,

dated February 24, 2014 27

F Email of Dr. Lukcs to Ms. Lalumiere,

dated February 24, 2014 30

G Email of Ms. Patrice Bellerose to Dr. Lukcs,

dated February 24, 2014 33

H Email of Dr. Lukcs to Ms. Bellerose,

dated February 24, 2014 37

I Email of Ms. Bellerose to Dr. Lukcs, including

attachment (Redacted File),

dated March 19, 2014 41

J Letter of Dr. Lukcs to the Agency,

dated March 24, 2014 164

K Letter of Mr. Geoffrey C. Hare, Chair and Chief

Executive Ofcer of the Agency, to Dr. Lukcs,

dated March 26, 2014 167

3 Transcript of cross-examination of Ms. Patrice Bellerose

on her afdavit sworn on July 29, 2014 170

4 Memorandum of Fact and Law of the Applicant 198

PART I STATEMENT OF FACTS 198

A. Overview 198

B. Background: the Agency and the open court

principle 199

C. The Agencys practice with respect to viewing

tribunal les 200

D. The Applicants request to view a tribunal le 201

PART II STATEMENT OF THE POINTS IN ISSUE 205

PART III STATEMENT OF SUBMISSIONS 206

A. Standard of review: correctness 207

B. Open court principle and s. 2(b) of the Charter 207

C. Tribunal les fall within the exclusions and/or the

exceptions to the Privacy Act 214

D. Inapplicability of the Privacy Act: the Oakes test 217

E. Remedies 218

F. Costs 222

PART IV ORDER SOUGHT 223

PART V LIST OF AUTHORITIES 225

APPENDIX A STATUTES AND REGULATIONS 230

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms 231

sections 1 and 2 231

subsection 24(1) 233

Canada Transportation Act, S.C. 1996, c. 10,

sections 1-41 235

section 7 239

sections 17 and 19 242

Canadian Transportation Agency Rules (Dispute

Proceedings and Certain Rules Applicable to All

Proceedings), S.O.R./2014-104 247

subsection 7(2) 248

subsection 18(1) 249

section 19 250

subsection 31(2) 251

Schedule 5 254

Schedule 6 255

Canadian Transportation Agency General Rules,

S.O.R./2005-35 256

subsection 23(1) 257

subsection 23(6) 259

section 40 262

Federal Courts Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. F-7 263

section 18 264

section 18.1 265

section 28 267

paragraph 28(1)(k) 268

subsection 28(2) 269

Federal Courts Rules, S.O.R./98-106 270

Rule 81(1) 271

Privacy Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. P-21 272

paragraphs 8(2)(a) and 8(2)(b) 273

subparagraph 8(2)(m)(i) (English) 274

subparagraph 8(2)(m)(i) (French) 275

subsection 69(2) 277

Court File No.:

FEDERAL COURT OF APPEAL

BETWEEN:

DR. GBOR LUKCS

Applicant

and

CANADIAN TRANSPORTATION AGENCY

Respondent

NOTICE OF APPLICATION

TO THE RESPONDENT:

A PROCEEDING HAS BEEN COMMENCED by the Applicant. The relief

claimed by the Applicant appears on the following page.

THIS APPLICATION will be heard by the Court at a time and place to be xed

by the Judicial Administrator. Unless the Court orders otherwise, the place of

hearing will be as requested by the Applicant. The Applicant requests that this

application be heard at the Federal Court of Appeal in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

IF YOU WISH TO OPPOSE THIS APPLICATION, to receive notice of any step

in the application or to be served with any documents in the application, you

or a solicitor acting for you must prepare a notice of appearance in Form 305

prescribed by the Federal Courts Rules and serve it on the Applicants solicitor,

or where the applicant is self-represented, on the Applicant, WITHIN 10 DAYS

after being served with this notice of application.

Copies of the Federal Courts Rules, information concerning the local ofces of

the Court and other necessary information may be obtained on request to the

Administrator of this Court at Ottawa (telephone 613-992-4238) or at any local

ofce.

1

- 2 -

IF YOU FAIL TO OPPOSE THIS APPLICATION, JUDGMENT MAY BE GIVEN

IN YOUR ABSENCE AND WITHOUT FURTHER NOTICE TO YOU.

Date: April 22, 2014 Issued by:

Address of

local ofce: Federal Court of Appeal

1801 Hollis Street

Halifax, Nova Scotia

TO: CANADIAN TRANSPORTATION AGENCY

15 Eddy Street

Gatineau, Quebec J8X 4B3

Ms. Cathy Murphy, Secretary

Tel: 819-997-0099

Fax: 819-953-5253

2

- 3 -

APPLICATION

This is an application for judicial review in respect of:

(a) the practices of the Canadian Transportation Agency (Agency) related

to the rights of the public, pursuant to the open-court principle, to view

information provided in the course of adjudicative proceedings; and

(b) the refusal of the Agency to allow the Applicant to view unredacted doc-

uments in File No. M4120-3/13-05726 of the Agency, even though no

condentiality order has been sought or made in that le.

The Applicant makes application for:

1. a declaration that adjudicative proceedings before the Canadian Trans-

portation Agency are subject to the constitutionally protected open-court

principle;

2. a declaration that all information, including but not limited to documents

and submissions, provided to the Canadian Transportation Agency in the

course of adjudicative proceedings are part of the public record in their

entirety, unless condentiality was sought and granted in accordance

with the Agencys General Rules;

3. a declaration that members of the public are entitled to view all informa-

tion, including but not limited to documents and submissions, provided

to the Canadian Transportation Agency in the course of adjudicative pro-

ceedings, unless condentiality was sought and granted in accordance

with the Agencys General Rules;

4. a declaration that information provided to the Canadian Transportation

Agency in the course of adjudicative proceedings fall within the excep-

tions of subsections 69(2) and/or 8(2)(a) and/or 8(2)(b) and/or 8(2)(m)

of the Privacy Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. P-21;

3

- 4 -

5. in the alternative, a declaration that provisions of the Privacy Act, R.S.C.

1985, c. P-21 are inapplicable with respect to information, including but

not limited to documents and submissions, provided to the Canadian

Transportation Agency in the course of adjudicative proceedings to the

extent that these provisions limit the rights of the public to view such in-

formation pursuant to subsection 2(b) of the Canadian Charter of Rights

and Freedoms;

6. a declaration that the power to determine questions related to conden-

tiality of information provided in the course of adjudicative proceedings

before the Canadian Transportation Agency is reserved to Members of

the Agency, and cannot be delegated to Agency Staff;

7. an order of a mandamus, directing the Canadian Transportation Agency

to provide the Applicant with unredacted copies of the documents in File

No. M4120-3/13-05726, or otherwise allow the Applicant and/or others

on his behalf to view unredacted copies of these documents;

8. costs and/or reasonable out-of-pocket expenses of this application;

9. such further and other relief or directions as the Applicant may request

and this Honourable Court deems just.

The grounds for the application are as follows:

1. The Canadian Transportation Agency (Agency), established by the

Canada Transportation Act, S.C. 1996, c. 10 (CTA), has a broad man-

date in respect of all transportation matters under the legislative author-

ity of Parliament. The Agency performs two key functions:

(a) as a quasi-judicial tribunal, the Agency resolves commercial and

consumer transportation-related disputes; and

(b) as an economic regulator, the Agency makes determinations and

issues licenses and permits to carriers which function within the

ambit of Parliaments authority.

4

- 5 -

2. The present application challenges the failure of the Agency to comply,

in practice, with the open-court principle and/or its own General Rules

and/or Privacy Statement with respect to the open-court principle in the

context of the right of the public to view information, including but not

limited to documents and submissions, provided to the Agency in the

course of adjudicative proceedings.

A. The Agencys General Rules

3. The Canadian Transportation Agency General Rules, S.O.R./2005-35,

contain detailed provisions implementing the open-court principle, and

provide for procedures for claiming condentiality:

23. (1) The Agency shall place on its public record any

document led with it in respect of any proceeding unless

the person ling the document makes a claim for its con-

dentiality in accordance with this section.

23. (5) A person making a claim for condentiality shall

indicate

(a) the reasons for the claim, including, if any specic

direct harm is asserted, the nature and extent of

the harm that would likely result to the person mak-

ing the claim for condentiality if the document were

disclosed; and

(b) whether the person objects to having a version of

the document from which the condential informa-

tion has been removed placed on the public record

and, if so, shall state the reasons for objecting.

23. (6) A claim for condentiality shall be placed on the

public record and a copy shall be provided, on request, to

any person.

24. (2) The Agency shall place a document in respect of

which a claim for condentiality has been made on the

public record if the document is relevant to the proceed-

ing and no specic direct harm would likely result from its

disclosure or any demonstrated specic direct harm is not

sufcient to outweigh the public interest in having it dis-

closed.

5

- 6 -

24. (4) If the Agency determines that a document in re-

spect of which a claim for condentiality has been made is

relevant to a proceeding and the specic direct harm likely

to result from its disclosure justies a claim for conden-

tiality, the Agency may

(a) order that the document not be placed on the public

record but that it be maintained in condence;

(b) order that a version or a part of the document from

which the condential information has been

removed be placed on the public record;

(c) order that the document be disclosed at a hearing

to be conducted in private;

(d) order that the document or any part of it be provided

to the parties to the proceeding, or only to their so-

licitors, and that the document not be placed on the

public record; or

(e) make any other order that it considers appropriate.

B. The Agencys Privacy Statement

4. The Agencys Privacy Statement states, among other things, that:

Open Court Principle

As a quasi-judicial tribunal operating like a court, the Cana-

dian Transportation Agency is bound by the constitutionally

protected open-court principle. This principle guarantees

the publics right to know how justice is administered and

to have access to decisions rendered by administrative tri-

bunals.

Pursuant to the General Rules, all information led with

the Agency becomes part of the public record and may be

made available for public viewing.

5. A copy of the Agencys Privacy Statement is provided to parties at the

commencement of adjudicative proceedings.

6

- 7 -

C. The Agencys practice

6. On February 14, 2014, the Applicant learned about Decision No. 55-C-

A-2014 that the Agency made in File No. M4120-3/13-05726.

7. On February 14, 2014, the Applicant sent an email to the Agency with

the subject line Request to view le no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to

s. 2(b) of the Charter and the email stated:

I would like to view the public documents in le no. M4120-

3/13-05726.

Due the public interest in the case, in which a nal decision

has been released today, the present request is urgent.

8. On February 17, 2014, the Applicant wrote to the Agency to follow up on

his request.

9. On February 17, 2014, Ms. Odette Lalumiere, Senior Counsel of the

Agency, advised the Applicant that Your request is being processed by

Ms Belleroses group.

10. On February 21 2014, the Applicant wrote to the Agency to follow up

again on his request.

11. On February 24, 2014, Ms. Lalumiere wrote to the Applicant again that

your request is being processed by Ms. Belleroses group. Ms. Patrice

Bellerose is the Information Services, Shared Services Projects & ATIP

Coordinator of the Agency.

12. On March 19, 2014, after multiple email exchanges, Ms. Bellerose sent

an email to the Applicant stating:

Please nd attached copies of records in response to your

request to view le 4120-3/13-05726.

The email had as an attachment a PDF le called AI-2013-00081.PDF

that consisted of 121 numbered pages, and pages 1, 27-39, 41, 45, 53-

56, 62-64, 66, 68-77, 81-87, 89, 90-113, and 115 were partially redacted

(Redacted File).

7

- 8 -

13. The Redacted File contained no claim for condentiality as stipulated

by section 23 of the Agencys General Rules, nor any decision by the

Agency directing that certain documents or portions thereof be treated

as condential.

14. Information that was redacted from the Redacted File included, among

other things:

(a) name and/or work email address of counsel acting for Air Canada

in the proceeding (e.g., pages 1, 27, 28, 36, 37, 45, 72, 75);

(b) names of Air Canada employees involved (e.g., pages 29, 31, 62,

64, 84, 87, 90, 92); and

(c) substantial portions of submissions and evidence (e.g., pages 41,

54-56, 63, 68-70, 85, 94, 96, 100-112).

15. On March 24, 2014, the Applicant made a written demand to the Agency

to be provided with unredacted copies of all documents in File No.

M4120-3/13-05726 with respect to which no condentiality order was

made by a Member of the Agency.

16. On March 26, 2014, Mr. Geoffrey C. Hare, hair and Chief Executive Of-

cer of the Agency, wrote to the Applicant, among other things, that:

The Canadian Transportation Agency (Agency) is a gov-

ernment institution which was included in the schedule to

the Privacy Act (Act) in 1982. [...]

[...] Section 8 of the Act is clear that, except for specic ex-

ceptions found in that section, personal information under

the control of a government institution shall not, without the

consent of the individual to whom it relates, be disclosed

by that institution. [...]

Although Agency case les are available to the public for

consultation in accordance with the open court principle,

personal information contained in the les such as an indi-

viduals home address, personal email address, personal

phone number, date of birth, nancial details, social in-

8

- 9 -

surance number, drivers license number, or credit card or

passport details, is not available for consultation.

The le you requested has such sensitive personal infor-

mation and it has therefore been removed by the Agency

as it required under the Act.

17. Even if the aforementioned interpretation of the Privacy Act were correct,

which is explicitly denied, it does not explain the sweeping redactions in

the Redacted File, which go beyond the types of information mentioned

in Mr. Hares letter.

D. The open-court principle

18. Long before the Charter, the doctrine of open court had been well es-

tablished at common law. In Scott v. Scott, [1913] A.C. 419 (H.L.), Lord

Shaw held that Publicity is the very soul of justice. It is the keenest

spur to exertion and the surest of all guards against improbity. It keeps

the judge himself while trying under trial. On the same theme, Justice

Brandeis of the American Supreme Court has famously remarked that

Sunlight is the best disinfectant.

19. Openness of proceedings is the rule, and covertness is the exception;

sensibilities of the individuals involved are no basis for exclusion of the

public from judicial proceedings (A.G. (Nova Scotia) v. MacIntyre, [1982]

1 SCR 175, at p. 185). The open court principle has been described as

a hallmark of a democratic society and is inextricably tied to freedom of

expression guaranteed by s. 2(b) of the Charter (CBC v. New Brunswick

(Attorney General), [1996] 3 SCR 480, paras. 22-23).

20. Since the adoption of the Charter, it is true that the open door doctrine

has been applied to certain administrative tribunals. While the bulk of

precedents have been in the context of court proceedings, there has

been an extension in the application of the doctrine to those proceedings

where tribunals exercise quasi-judicial functions, which is to say that, by

statute, they have the jurisdiction to determine the rights and duties of

the parties before them.

9

- 10 -

21. The open court principle also applies to quasi-judicial proceedings be-

fore tribunals (Germain v. Automobile Injury Appeal Commission, 2009

SKQB 106, para. 104).

22. Adjudicative proceedings before the Agency are quasi-judicial proceed-

ings, because the Canada Transportation Act confers upon the Agency

the jurisdiction to determine the rights and duties of the parties. Thus,

the open-court principle applies to such proceedings before the Agency.

23. The Agency itself has recognized that it is bound by the open-court prin-

ciple (Tanenbaum v. Air Canada, Decision No. 219-A-2009). Sections

23-24 of the Agencys General Rules reect this principle: documents

provided to the Agency are public, unless the person ling leads evi-

dence and arguments that meet the test for granting a condentiality

order. Such determinations are made in accordance with the principles

set out in Sierra Club of Canada v. Canada (Minister of Finance), 2002

SCC 41.

24. Thus, the open-court principle dictates that all documents in an adju-

dicative le of the Agency must be made available for public viewing,

unless the Agency made a decision during the proceeding that certain

documents or portions thereof be treated condentially. Public viewing

of documents is particularly important in les that have been heard in

writing, without an oral hearing.

E. The Privacy Act does not trump the open-court principle

25. There can be many privacy-related considerations to granting a con-

dentiality order, such as protection of the innocent or protection of a

vulnerable party to ensure access to justice (A.B. v. Bragg Communi-

cations Inc., 2012 SCC 46); however, privacy of the parties in and on

its own does not trump the open-court principle (A.G. (Nova Scotia) v.

MacIntyre, [1982] 1 SCR 175, at p. 185).

26. The Privacy Act cannot override the constitutional principles that are in-

terwoven into the open court principle (El-Helou v. Courts Administration

Service, 2012 CanLII 30713 (CA PSDPT), paras. 67-80).

10

- 11 -

27. Due to the open court principle as well as section 23(1) of the Agencys

General Rules, personal information that the Agency received as part of

its quasi-judicial functions, is publicly available.

28. Under subsection 69(2) of the Privacy Act, sections 7 and 8 do not apply

to personal information that is publicly available. Therefore, personal in-

formation that is properly before the Agency in its quasi-judicial functions

is not subject to the restrictions of the Privacy Act.

29. In the alternative, if section 8 of the Privacy Act does apply, then per-

sonal information that was provided to the Agency in the course of an

adjudicative proceeding may be disclosed pursuant to the exceptions

set out in subsections 8(2)(a) and/or 8(2)(b) and/or 8(2)(m) of the Pri-

vacy Act (El-Helou v. Courts Administration Service, 2012 CanLII 30713

(CA PSDPT), paras. 67-80).

30. In the alternative, if the Privacy Act does purport to limit the rights of the

public to view information provided to the Agency in the course of adju-

dicative proceedings, then such limitation is inconsistent with subsection

2(b) of the Canadian Charter of Right and Freedoms, and it ought to be

read down so as not to be applicable to such information.

F. Authority to determine what to redact

31. According to section 7(2) of the CTA, the Agency consists of permanent

and temporary Members appointed in accordance with the CTA. Only

these Members may exercise the quasi-judicial powers of the Agency,

and the Act contains no provisions that would allow delegation of these

powers.

32. Determination of condentiality of documents provided in the course of

an adjudicative proceeding before the Agency, including which portions

ought to be redacted, falls squarely within the Agencys quasi-judicial

functions. Consequently, these powers can only be exercised by Mem-

bers of the Agency, and cannot be delegated to Agency Staff, as hap-

pened with the Applicants request in the present case.

11

- 12 -

G. Statutory provisions

33. The Applicant will also rely on the following statutory provisions:

(a) Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and in particular, sub-

section 2(b) and section 24(1);

(b) Canada Transportation Act, S.C. 1996, c. 10;

(c) Canadian Transportation Agency General Rules, S.O.R./2005-35,

and in particular, sections 23 and 24;

(d) Federal Courts Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. F-7, and in particular, sec-

tions 18.1 and 28; and

(e) Federal Court Rules, S.O.R./98-106, and in particular, Rule 300.

34. Such further and other grounds as the Applicant may advise and this

Honourable Court permits.

This application will be supported by the following material:

1. Afdavit of Dr. Gbor Lukcs, to be served.

2. Such further and additional materials as the Applicant may advise and

this Honourable Court may allow.

April 22, 2014

DR. GBOR LUKCS

Halifax, Nova Scotia

lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca

Applicant

12

13

Court File No.: A-218-14

FEDERAL COURT OF APPEAL

BETWEEN:

DR. GBOR LUKCS

Applicant

and

CANADIAN TRANSPORTATION AGENCY

Respondent

AFFIDAVIT OF DR. GBOR LUKCS

(Afrmed: April 25, 2014)

I, Dr. Gbor Lukcs, of the City of Halifax in the Regional Municipality of Halifax,

in the Province of Nova Scotia, AFFIRM THAT:

1. I am a Canadian citizen, a frequent traveller, and an air passenger rights

advocate. My activities in the latter capacity include:

(a) ling approximately two dozen successful regulatory complaints

with the Canadian Transportation Agency (the Agency), result-

ing in airlines being ordered to implement policies that reect the

legal principles of the Montreal Convention or otherwise offer bet-

ter protection to passengers;

(b) promoting air passenger rights through the press and social me-

dia; and

(c) referring passengers mistreated by airlines to legal information

and resources.

14

2. On September 4, 2013, the Consumers Association of Canada recog-

nized my achievements in the area of air passenger rights by awarding

me its Order of Merit for singlehandedly initiating Legal Action resulting

in revision of Air Canada unfair practices regarding Over Booking.

3. On February 14, 2014, I learned about Decision No. 55-C-A-2014 that

the Canadian Transportation Agency (Agency) made in File No. M4120-

3/13-05726. Later that day, I sent an email to the Agency with the subject

line Request to viewle no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s. 2(b) of the

Charter and the email stated:

I would like to view the public documents in le no. M4120-

3/13-05726.

Due the public interest in the case, in which a nal decision

has been released today, the present request is urgent.

A copy of my email, dated February 14, 2014, is attached and marked

as Exhibit A.

4. Since I received no answer to my request, on February 17, 2014, I sent

a follow-up email to the Agency, a copy of which is attached and marked

as Exhibit B.

5. On February 17, 2014, Ms. Odette Lalumiere, Senior Counsel of the

Agency, advised me by email that Your request is being processed by

Ms Belleroses group. A copy of Ms. Lalumieres email, dated February

17, 2014, is attached and marked as Exhibit C.

6. On February 21, 2014, I sent a second follow-up email to the Agency, a

copy of which is attached and marked as Exhibit D.

15

7. On February 24, 2014, Ms. Lalumiere wrote me again that your request

is being processed by Ms. Belleroses group. A copy of Ms. Lalumieres

email, dated February 24, 2014, is attached and marked as Exhibit E.

8. On February 24, 2014, I expressed concern to Ms. Lalumiere about the

delay related to my request. A copy of my email to Ms. Lalumiere, dated

February 24, 2014, is attached and marked as Exhibit F.

9. On February 24, 2014, Ms. Patrice Bellerose, the Information Services,

Shared Services Projects & ATIP Coordinator of the Agency, advised

me that:

As previously mentioned we are working on your requests.

We have multiple priorities and I have noted the urgency

on the request. We will provide you with the public records

as soon as we can. [Emphasis added.]

A copy of Ms. Belleroses email, dated February 24, 2014, is attached

and marked as Exhibit G.

10. On February 24, 2014, I wrote to Ms. Bellerose to express concern over

the notion of processing a request to view a public le:

With due respect, I fail to see why scanning documents in

a public le would require massive resources or anything

but a few minutes to put into a scanner.

I do remain profoundly concerned that you are usurping

the authority of Members of the Agency to decide what

documents or portions of documents are public, and that

you are unlawfully engaging in withholding public docu-

ments, in violation of my rights under s. 2(b) of Charter.

A copy of my email to Ms. Bellerose, dated February 24, 2014, is at-

tached and marked as Exhibit H.

16

11. On March 19, 2014, Ms. Bellerose sent me an email stating:

Please nd attached copies of records in response to your

request to view le 4120-3/13-05726.

The email had as an attachment a PDF le called AI-2013-00081.PDF

that consisted of 121 numbered pages. A copy of Ms. Belleroses email,

dated March 19, 2014, including its attachment, is attached and marked

as Exhibit I.

12. On March 24, 2014, I made a written demand to the Agency to be

provided with unredacted copies of all documents in File No. M4120-

3/13-05726 with respect to which no condentiality order was made by

a Member of the Agency. A copy of my March 24, 2014 letter is attached

and marked as Exhibit J.

13. On March 26, 2014, Mr. Geoffrey C. Hare, Chair and Chief Executive

Ofcer of the Agency, wrote to me, among other things, that:

The Canadian Transportation Agency (Agency) is a gov-

ernment institution which was included in the schedule to

the Privacy Act (Act) in 1982. [...]

[...] Section 8 of the Act is clear that, except for specic ex-

ceptions found in that section, personal information under

the control of a government institution shall not, without the

consent of the individual to whom it relates, be disclosed

by that institution. [...]

Although Agency case les are available to the public for

consultation in accordance with the open court principle,

personal information contained in the les such as an indi-

viduals home address, personal email address, personal

phone number, date of birth, nancial details, social in-

surance number, drivers license number, or credit card or

passport details, is not available for consultation.

17

The le you requested has such sensitive personal infor-

mation and it has therefore been removed by the Agency

as it required under the Act.

A copy of Mr. Hares letter, dated March 26, 2014, is attached and marked

as Exhibit K.

AFFIRMED before me at the City of Halifax

in the Regional Municipality of Halifax

on April 25, 2014. Dr. Gbor Lukcs

Halifax, NS

lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca

18

This is Exhibit A to the Afdavit of Dr. Gbor Lukacs

afrmed before me on April 25, 2014

Signature

From lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca Fri Feb 14 16:26:02 2014

Date: Fri, 14 Feb 2014 16:25:59 -0400 (AST)

From: Gabor Lukacs <lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca>

To: secretaire-secretary@otc-cta.gc.ca

Cc: Patrice Bellerose <Patrice.Bellerose@otc-cta.gc.ca>, Odette Lalumiere <Odette.Lal

umiere@otc-cta.gc.ca>

Subject: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s. 2(b) of the Charter

Dear Madam Secretary,

I would like to view the public documents in file no. M4120-3/13-05726.

Due the public interest in the case, in which a final decision has been

released today, the present request is urgent.

Sincerely yours,

Dr. Gabor Lukacs

19

20

This is Exhibit B to the Afdavit of Dr. Gbor Lukacs

afrmed before me on April 25, 2014

Signature

From lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca Mon Feb 17 17:08:22 2014

Date: Mon, 17 Feb 2014 17:08:19 -0400 (AST)

From: Gabor Lukacs <lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca>

To: secretaire-secretary@otc-cta.gc.ca

Cc: Patrice Bellerose <Patrice.Bellerose@otc-cta.gc.ca>, Odette Lalumiere <Odette.Lal

umiere@otc-cta.gc.ca>

Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s. 2(b) of the Cha

rter

Dear Madam Secretary,

I am writing to follow-up on the matter below, which may be of some public

interest, and as such delay in your response may interfere with my rights

under s. 2(b) of the Charter.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Sincerely yours,

Dr. Gabor Lukacs

On Fri, 14 Feb 2014, Gabor Lukacs wrote:

> Dear Madam Secretary,

>

> I would like to view the public documents in file no. M4120-3/13-05726.

>

> Due the public interest in the case, in which a final decision has been

> released today, the present request is urgent.

>

> Sincerely yours,

> Dr. Gabor Lukacs

>

21

22

This is Exhibit C to the Afdavit of Dr. Gbor Lukacs

afrmed before me on April 25, 2014

Signature

From Odette.Lalumiere@otc-cta.gc.ca Mon Feb 17 17:36:26 2014

Date: Mon, 17 Feb 2014 16:35:51 -0500

From: Odette Lalumiere <Odette.Lalumiere@otc-cta.gc.ca>

To: lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca, secretaire-secretary <secretaire-secretary@otc-cta.

gc.ca>

Cc: Patrice Bellerose <Patrice.Bellerose@otc-cta.gc.ca>

Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s. 2 (b) ofthe Cha

rter

Mr Lukacs

Your request is being processed by Ms Belleroses group.

Odette Lalumi??re

From: Gabor Lukacs

Sent: Monday, February 17, 2014 4:07 PM

To: secretaire-secretary

Cc: Odette Lalumiere; Patrice Bellerose

Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s. 2(b) of

the Charter

Dear Madam Secretary,

I am writing to follow-up on the matter below, which may be of some public

interest, and as such delay in your response may interfere with my rights

under s. 2(b) of the Charter.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Sincerely yours,

Dr. Gabor Lukacs

On Fri, 14 Feb 2014, Gabor Lukacs wrote:

> Dear Madam Secretary,

>

> I would like to view the public documents in file no. M4120-3/13-05726.

>

> Due the public interest in the case, in which a final decision has been

> released today, the present request is urgent.

>

> Sincerely yours,

> Dr. Gabor Lukacs

>

23

24

This is Exhibit D to the Afdavit of Dr. Gbor Lukacs

afrmed before me on April 25, 2014

Signature

From lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca Fri Feb 21 14:19:58 2014

Date: Fri, 21 Feb 2014 14:19:55 -0400 (AST)

From: Gabor Lukacs <lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca>

To: Odette Lalumiere <Odette.Lalumiere@otc-cta.gc.ca>

Cc: secretaire-secretary <secretaire-secretary@otc-cta.gc.ca>, Patrice Bellerose <Pat

rice.Bellerose@otc-cta.gc.ca>

Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s. 2 (b) of the Ch

arter

Dear Ms. Lalumiere and Ms. Bellerose,

I am writing to follow up on the request below. I am profoundly concerned

about what transpires as the Agency attempting to frustrate my rights

pursuant to s. 2(b) of the Charter.

Yours very truly,

Dr. Gabor Lukacs

On Mon, 17 Feb 2014, Odette Lalumiere wrote:

> Mr Lukacs

> Your request is being processed by Ms Belleroses group.

>

> Odette Lalumi??re

>

>

>

> From: Gabor Lukacs

> Sent: Monday, February 17, 2014 4:07 PM

> To: secretaire-secretary

> Cc: Odette Lalumiere; Patrice Bellerose

> Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s. 2(b)

> of the Charter

>

> Dear Madam Secretary,

>

> I am writing to follow-up on the matter below, which may be of some public

> interest, and as such delay in your response may interfere with my rights

> under s. 2(b) of the Charter.

>

> I look forward to hearing from you.

>

> Sincerely yours,

> Dr. Gabor Lukacs

>

>

> On Fri, 14 Feb 2014, Gabor Lukacs wrote:

>

> > Dear Madam Secretary,

> >

> > I would like to view the public documents in file no. M4120-3/13-05726.

> >

> > Due the public interest in the case, in which a final decision has been

> > released today, the present request is urgent.

> >

> > Sincerely yours,

> > Dr. Gabor Lukacs

> >

>

25

>

26

27

This is Exhibit E to the Afdavit of Dr. Gbor Lukacs

afrmed before me on April 25, 2014

Signature

From Odette.Lalumiere@otc-cta.gc.ca Mon Feb 24 12:44:14 2014

Date: Mon, 24 Feb 2014 11:44:01 -0500

From: Odette Lalumiere <Odette.Lalumiere@otc-cta.gc.ca>

To: Gabor Lukacs <lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca>

Cc: Patrice Bellerose <Patrice.Bellerose@otc-cta.gc.ca>, secretaire-secretary secreta

ire-secretary <secretaire-secretary@otc-cta.gc.ca>

Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s. 2 (b) of the Ch

arter

[ The following text is in the "Windows-1252" character set. ]

[ Your display is set for the "ISO-8859-1" character set. ]

[ Some characters may be displayed incorrectly. ]

Mr. Lukacs,

As indicated in my e-mail of February 17, 2014, your request is being

processed by Ms. Belleroses group.

Odette Lalumire

Avocate principale/Senior Counsel

Direction des services juridiques/Legal Services Directorate

Office des transports du Canada/Canadian Transportation Agency

Tl./Tel.: 819 994-2226

odette.lalumiere@otc-cta.gc.ca

>>> Gabor Lukacs <lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca> 21/02/2014 1:19 PM >>>

Dear Ms. Lalumiere and Ms. Bellerose,

I am writing to follow up on the request below. I am profoundly

concerned

about what transpires as the Agency attempting to frustrate my rights

pursuant to s. 2(b) of the Charter.

Yours very truly,

Dr. Gabor Lukacs

On Mon, 17 Feb 2014, Odette Lalumiere wrote:

> Mr Lukacs

> Your request is being processed by Ms Belleroses group.

>

> Odette Lalumi??re

>

>

>

> From: Gabor Lukacs

> Sent: Monday, February 17, 2014 4:07 PM

> To: secretaire-secretary

> Cc: Odette Lalumiere; Patrice Bellerose

> Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s.

2(b)

> of the Charter

>

> Dear Madam Secretary,

>

> I am writing to follow-up on the matter below, which may be of some

28

public

> interest, and as such delay in your response may interfere with my

rights

> under s. 2(b) of the Charter.

>

> I look forward to hearing from you.

>

> Sincerely yours,

> Dr. Gabor Lukacs

>

>

> On Fri, 14 Feb 2014, Gabor Lukacs wrote:

>

> > Dear Madam Secretary,

> >

> > I would like to view the public documents in file no.

M4120-3/13-05726.

> >

> > Due the public interest in the case, in which a final decision has

been

> > released today, the present request is urgent.

> >

> > Sincerely yours,

> > Dr. Gabor Lukacs

> >

>

>

29

30

This is Exhibit F to the Afdavit of Dr. Gbor Lukacs

afrmed before me on April 25, 2014

Signature

From lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca Mon Feb 24 12:57:22 2014

Date: Mon, 24 Feb 2014 12:57:20 -0400 (AST)

From: Gabor Lukacs <lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca>

To: Odette Lalumiere <Odette.Lalumiere@otc-cta.gc.ca>

Cc: Patrice Bellerose <Patrice.Bellerose@otc-cta.gc.ca>, secretaire-secretary secreta

ire-secretary <secretaire-secretary@otc-cta.gc.ca>

Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s. 2 (b) of the Ch

arter

[ The following text is in the "Windows-1252" character set. ]

[ Your display is set for the "ISO-8859-1" character set. ]

[ Some characters may be displayed incorrectly. ]

Ms. Lalumiere,

Although you keep repeating that the request is being processed, I have

received no communication from Ms. Bellerose with respect to my request,

even though the request was made on February 14, 2014.

With due respect, the obligation under s. 2(b) of the Charter is not met

by the Agency by pointing at various employees or groups of employees.

Thus, I reiterate my request that the Agency provide me with a reasonable

opportunity to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726.

Yours very truly,

Dr. Gabor Lukacs

On Mon, 24 Feb 2014, Odette Lalumiere wrote:

> Mr. Lukacs,

> As indicated in my e-mail of February 17, 2014, your request is being

> processed by Ms. Belleroses group.

>

>

>

> Odette Lalumire

> Avocate principale/Senior Counsel

> Direction des services juridiques/Legal Services Directorate

> Office des transports du Canada/Canadian Transportation Agency

> Tl./Tel.: 819 994-2226

>

> odette.lalumiere@otc-cta.gc.ca

>

>

>>>> Gabor Lukacs <lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca> 21/02/2014 1:19 PM >>>

> Dear Ms. Lalumiere and Ms. Bellerose,

>

> I am writing to follow up on the request below. I am profoundly

> concerned

> about what transpires as the Agency attempting to frustrate my rights

> pursuant to s. 2(b) of the Charter.

>

> Yours very truly,

> Dr. Gabor Lukacs

>

>

>

>

31

> On Mon, 17 Feb 2014, Odette Lalumiere wrote:

>

>> Mr Lukacs

>> Your request is being processed by Ms Belleroses group.

>>

>> Odette Lalumi??re

>>

>>

>>

>> From: Gabor Lukacs

>> Sent: Monday, February 17, 2014 4:07 PM

>> To: secretaire-secretary

>> Cc: Odette Lalumiere; Patrice Bellerose

>> Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s.

> 2(b)

>> of the Charter

>>

>> Dear Madam Secretary,

>>

>> I am writing to follow-up on the matter below, which may be of some

> public

>> interest, and as such delay in your response may interfere with my

> rights

>> under s. 2(b) of the Charter.

>>

>> I look forward to hearing from you.

>>

>> Sincerely yours,

>> Dr. Gabor Lukacs

>>

>>

>> On Fri, 14 Feb 2014, Gabor Lukacs wrote:

>>

>>> Dear Madam Secretary,

>>>

>>> I would like to view the public documents in file no.

> M4120-3/13-05726.

>>>

>>> Due the public interest in the case, in which a final decision has

> been

>>> released today, the present request is urgent.

>>>

>>> Sincerely yours,

>>> Dr. Gabor Lukacs

>>>

>>

>>

>

32

33

This is Exhibit G to the Afdavit of Dr. Gbor Lukacs

afrmed before me on April 25, 2014

Signature

From Patrice.Bellerose@otc-cta.gc.ca Mon Feb 24 13:47:16 2014

Date: Mon, 24 Feb 2014 12:46:55 -0500

From: Patrice Bellerose <Patrice.Bellerose@otc-cta.gc.ca>

To: lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca, Odette Lalumiere <Odette.Lalumiere@otc-cta.gc.ca>

Cc: secretaire-secretary <secretaire-secretary@otc-cta.gc.ca>

Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s. 2 (b) ofthe Cha

rter

[ The following text is in the "UTF-8" character set. ]

[ Your display is set for the "ISO-8859-1" character set. ]

[ Some characters may be displayed incorrectly. ]

Hello Mr. Lukacs,

As previously mentioned we are working on your requests. We have multiple

priorities and I have noted the urgency on the request. We will provide you with

the public records as soon as we can.

Thank you.

Patrice Bellerose

From: Gabor Lukacs

Sent: Monday, February 24, 2014 11:56 AM

To: Odette Lalumiere

Cc: Patrice Bellerose; secretaire-secretary

Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s. 2 (b) of

the Charter

Ms. Lalumiere,

Although you keep repeating that the request is being processed, I have

received no communication from Ms. Bellerose with respect to my request,

even though the request was made on February 14, 2014.

With due respect, the obligation under s. 2(b) of the Charter is not met

by the Agency by pointing at various employees or groups of employees.

Thus, I reiterate my request that the Agency provide me with a reasonable

opportunity to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726.

Yours very truly,

Dr. Gabor Lukacs

On Mon, 24 Feb 2014, Odette Lalumiere wrote:

> Mr. Lukacs,

> As indicated in my e-mail of February 17, 2014, your request is being

> processed by Ms. Belleroses group.

>

>

>

> Odette Lalumire

> Avocate principale/Senior Counsel

> Direction des services juridiques/Legal Services Directorate

> Office des transports du Canada/Canadian Transportation Agency

> Tl./Tel.: 819 994-2226

34

>

> odette.lalumiere@otc-cta.gc.ca

>

>

>>>> Gabor Lukacs <lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca> 21/02/2014 1:19 PM >>>

> Dear Ms. Lalumiere and Ms. Bellerose,

>

> I am writing to follow up on the request below. I am profoundly

> concerned

> about what transpires as the Agency attempting to frustrate my rights

> pursuant to s. 2(b) of the Charter.

>

> Yours very truly,

> Dr. Gabor Lukacs

>

>

>

>

> On Mon, 17 Feb 2014, Odette Lalumiere wrote:

>

>> Mr Lukacs

>> Your request is being processed by Ms Belleroses group.

>>

>> Odette Lalumi??re

>>

>>

>>

>> From: Gabor Lukacs

>> Sent: Monday, February 17, 2014 4:07 PM

>> To: secretaire-secretary

>> Cc: Odette Lalumiere; Patrice Bellerose

>> Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s.

> 2(b)

>> of the Charter

>>

>> Dear Madam Secretary,

>>

>> I am writing to follow-up on the matter below, which may be of some

> public

>> interest, and as such delay in your response may interfere with my

> rights

>> under s. 2(b) of the Charter.

>>

>> I look forward to hearing from you.

>>

>> Sincerely yours,

>> Dr. Gabor Lukacs

>>

>>

>> On Fri, 14 Feb 2014, Gabor Lukacs wrote:

>>

>>> Dear Madam Secretary,

>>>

>>> I would like to view the public documents in file no.

> M4120-3/13-05726.

>>>

>>> Due the public interest in the case, in which a final decision has

> been

>>> released today, the present request is urgent.

>>>

>>> Sincerely yours,

>>> Dr. Gabor Lukacs

35

>>>

>>

>>

>

36

37

This is Exhibit H to the Afdavit of Dr. Gbor Lukacs

afrmed before me on April 25, 2014

Signature

From lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca Mon Feb 24 17:22:24 2014

Date: Mon, 24 Feb 2014 17:22:20 -0400 (AST)

From: Gabor Lukacs <lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca>

To: Patrice Bellerose <Patrice.Bellerose@otc-cta.gc.ca>

Cc: Odette Lalumiere <Odette.Lalumiere@otc-cta.gc.ca>, secretaire-secretary <secretai

re-secretary@otc-cta.gc.ca>

Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s. 2 (b) ofthe Cha

rter

[ The following text is in the "UTF-8" character set. ]

[ Your display is set for the "ISO-8859-1" character set. ]

[ Some characters may be displayed incorrectly. ]

Ms. Bellerose,

Earlier, I asked you the following question, which you have not answer as

of yet:

> Can you please elaborate on what "processing" means in this context?

> My understanding is that there is a public file, and thus all that needs

> to be done is feed these documents into a scanner.

With due respect, I fail to see why scanning documents in a public file

would require massive resources or anything but a few minutes to put into

a scanner.

I do remain profoundly concerned that you are usurping the authority of

Members of the Agency to decide what documents or portions of documents

are public, and that you are unlawfully engaging in withholding public

documents, in violation of my rights under s. 2(b) of Charter.

I reiterate my request that you provide a clear explanation for the delay

and the meaning of "processing" in this context.

Sincerely yours,

Dr. Gabor Lukacs

On Mon, 24 Feb 2014, Patrice Bellerose wrote:

> Hello Mr. Lukacs,

> As previously mentioned we are working on your requests. We have multiple

> priorities and I have noted the urgency on the request. We will provide you

> with the public records as soon as we can.

> Thank you.

> Patrice Bellerose

>

>

>

>

>

>

> From: Gabor Lukacs

> Sent: Monday, February 24, 2014 11:56 AM

> To: Odette Lalumiere

> Cc: Patrice Bellerose; secretaire-secretary

> Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s. 2 (b)

> of the Charter

>

> Ms. Lalumiere,

38

>

> Although you keep repeating that the request is being processed, I have

> received no communication from Ms. Bellerose with respect to my request,

> even though the request was made on February 14, 2014.

>

> With due respect, the obligation under s. 2(b) of the Charter is not met

> by the Agency by pointing at various employees or groups of employees.

>

> Thus, I reiterate my request that the Agency provide me with a reasonable

> opportunity to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726.

>

> Yours very truly,

> Dr. Gabor Lukacs

>

>

>

>

> On Mon, 24 Feb 2014, Odette Lalumiere wrote:

>

> > Mr. Lukacs,

> > As indicated in my e-mail of February 17, 2014, your request is being

> > processed by Ms. Belleroses group.

> >

> >

> >

> > Odette Lalumire

> > Avocate principale/Senior Counsel

> > Direction des services juridiques/Legal Services Directorate

> > Office des transports du Canada/Canadian Transportation Agency

> > Tl./Tel.: 819 994-2226

> >

> > odette.lalumiere@otc-cta.gc.ca

> >

> >

> >>>> Gabor Lukacs <lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca> 21/02/2014 1:19 PM >>>

> > Dear Ms. Lalumiere and Ms. Bellerose,

> >

> > I am writing to follow up on the request below. I am profoundly

> > concerned

> > about what transpires as the Agency attempting to frustrate my rights

> > pursuant to s. 2(b) of the Charter.

> >

> > Yours very truly,

> > Dr. Gabor Lukacs

> >

> >

> >

> >

> > On Mon, 17 Feb 2014, Odette Lalumiere wrote:

> >

> >> Mr Lukacs

> >> Your request is being processed by Ms Belleroses group.

> >>

> >> Odette Lalumi??re

> >>

> >>

> >>

> >> From: Gabor Lukacs

> >> Sent: Monday, February 17, 2014 4:07 PM

> >> To: secretaire-secretary

> >> Cc: Odette Lalumiere; Patrice Bellerose

> >> Subject: Re: Request to view file no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s.

39

> > 2(b)

> >> of the Charter

> >>

> >> Dear Madam Secretary,

> >>

> >> I am writing to follow-up on the matter below, which may be of some

> > public

> >> interest, and as such delay in your response may interfere with my

> > rights

> >> under s. 2(b) of the Charter.

> >>

> >> I look forward to hearing from you.

> >>

> >> Sincerely yours,

> >> Dr. Gabor Lukacs

> >>

> >>

> >> On Fri, 14 Feb 2014, Gabor Lukacs wrote:

> >>

> >>> Dear Madam Secretary,

> >>>

> >>> I would like to view the public documents in file no.

> > M4120-3/13-05726.

> >>>

> >>> Due the public interest in the case, in which a final decision has

> > been

> >>> released today, the present request is urgent.

> >>>

> >>> Sincerely yours,

> >>> Dr. Gabor Lukacs

> >>>

> >>

> >>

> >

>

>

40

41

This is Exhibit I to the Afdavit of Dr. Gbor Lukacs

afrmed before me on April 25, 2014

Signature

From Patrice.Bellerose@otc-cta.gc.ca Wed Mar 19 13:59:48 2014

Date: Wed, 19 Mar 2014 12:58:42 -0400

From: Patrice Bellerose <Patrice.Bellerose@otc-cta.gc.ca>

To: Gabor Lukacs <lukacs@airpassengerrights.ca>

Cc: Cathy Murphy <Cathy.Murphy@otc-cta.gc.ca>, Odette Lalumiere <Odette.Lalumiere@otc

-cta.gc.ca>

Subject: Response to "Request to view file 4120-3/13-05726"

[ The following text is in the "Windows-1252" character set. ]

[ Your display is set for the "ISO-8859-1" character set. ]

[ Some characters may be displayed incorrectly. ]

Hello Mr. Lukacs,

Please find attached copies of records in response to your "request to

view file 4120-3/13-05726".

Thank you.

Patrice Bellerose

Gestionnaire principale | Senior Manager

Services dinformation, des projets de services partags et

coordinatrice de lAIPRP | Information Services, Shared Services

Projects & ATIP Coordinator

Office des transports du Canada | Canadian Transportation Agency

Bureau 1718 | Office 1718

15 rue Eddy, Gatineau (QC) K1A 0N9 | 15 Eddy St., Gatineau, QC K1A

0N9

Tlphone | Telephone 819-994-2564

Tlcopieur | Facsimile 819-997-6727

patrice.bellerose@otc-cta.gc.ca

[ Part 2, Application/PDF (Name: "AI-2013-00081.PDF") 15 MB. ]

[ Unable to print this part. ]

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

This is Exhibit J to the Afdavit of Dr. Gbor Lukacs

afrmed before me on April 25, 2014

Signature

Halifax, NS

lukacs@AirPassengerRights.ca

March 24, 2014

VIA EMAIL and FAX

The Secretary

Canadian Transportation Agency

Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0N9

Dear Madam Secretary:

Re: Request pursuant to the open court principle and s. 2(b) of the Charter

to view File No. M4120-3/13-05726

Heavily redacted documents received on March 19, 2014

I am writing to make a nal request, prior to making an application for judicial review, that the

Agency comply with its obligations under the open court principle and s. 2(b) of the Canadian

Charter of Rights and Freedoms, to make documents that are part of the public record available for

public viewing.

1. On February 14, 2014, I made a request to the Agency to view the public documents in le

no. M4120-3/13-05726 pursuant to s. 2(b) of the Charter.

2. In subsequent communications dated February 17, 21, and 24, 2014, I have reiterated that my

request was based on s. 2(b) of the Charter.

3. On March 19, 2014, I received an email from Ms. Bellerose, the Senior Manager of the Infor-

mation Services, Shared Services Projects & ATIP Coordinator of the Agency, stating that:

Please nd attached copies of records in response to your request to view le

4120-3/13-05726.

Ms. Belleroses email had a PDF le named AI-2013-00081.PDF attached, which contained

heavily redacted copies of documents in File No. M4120-13/13-05726.

165

March 24, 2014

Page 2 of 2

It is my position that providing redacted documents does not discharge the Agencys obligations

under the open court principle, because the le contains no condentiality order made by a Member

of the Agency pursuant to Rules 23-25 of the Canadian Transportation Agency General Rules,

S.O.R./2005-35.

My position is consistent with Rule 23(1) of the Canadian Transportation Agency General Rules:

The Agency shall place on its public record any document led with it in respect of

any proceeding unless the person ling the document makes a claim for its con-

dentiality in accordance with this section.

My position is also consistent with the Agencys Privacy Statement concerning the Agencys com-

plaint process:

In accordance with the values of the open court principle and pursuant to the Cana-

dian Transportation Agency General Rules, all information led with the Agency

becomes part of the public record and may be made available for public viewing.

Finally, I refer to Decision No. 219-A-2009 of the Agency, concerning the motion of Leslie Tenen-

baum for non-publication of his name and certain personal information, where the Agency ana-

lyzed in great detail its own obligations under the open court principle.

In light of the foregoing, I trust you agree with me that the documents in question were redacted

without lawful authority or authorization to do so, and in breach of the Agencys obligations under

the open court principle and s. 2(b) of the Charter.

Therefore, I am requesting that:

A. the present letter be brought to the attention of Mr. Geoffrey C. Hare, Chair and CEO of the

Agency; and

B. the Agency provide me, within ve (5) business days, with unredacted copies of all documents

in File No. M4120-3-/13-05726 with respect to which no condentiality order was made by a

Member of the Agency.

Kindly please conrm the receipt of this letter.

Yours very truly,

Dr. Gbor Lukcs

166

167

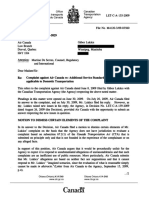

This is Exhibit K to the Afdavit of Dr. Gbor Lukacs

afrmed before me on April 25, 2014

Signature

168

169

GILLESPIEREPORTINGSERVICES,ADivisionof709387OntarioInc.,200130SlaterSt.OttawaOntarioK1P6E2

Tel:6132388501 Fax:6132381045 TollFree18002673926

Exami nat i on No. 14- 0775 Cour t Fi l e No. A- 218- 14

FEDERAL COURT OF APPEAL

B E T WE E N:

DR. GABOR LUKACS

APPLI CANT

- and

CANADI AN TRANSPORTATI ON AGENCY

RESPONDENT

**********************

CROSS- EXAMI NATI ON OF PATRI CE BELLEROSE ON HER AFFI DAVI T

SWORN J ULY 29, 2014, pur suant t o an appoi nt ment made on

consent of t he par t i es, t o be r epor t ed by Gi l l espi e

Repor t i ng Ser vi ces, on t he 21st day of August , 2014,

commenci ng at t he hour of 10: 29 i n t he f or enoon.

**********************

APPEARANCES:

Dr . Gabor Lukacs, f or t he Appl i cant

Mr . Si mon- Pi er r e Lessar d, f or t he Respondent

Thi s Cr oss- Exami nat i on was di gi t al l y r ecor ded by Gi l l espi e

Repor t i ng Ser vi ces at Ot t awa, Ont ar i o, havi ng been dul y appoi nt ed

f or t he pur pose.

170

GILLESPIEREPORTINGSERVICES,ADivisionof709387OntarioInc.,200130SlaterSt.OttawaOntarioK1P6E2

Tel:6132388501 Fax:6132381045 TollFree18002673926

( i )

INDEX

NAME OF WI TNESS: PATRI CE BELLEROSE

CROSS- EXAMI NATI ON BY: DR. GABOR LUKACS

NUMBER OF PAGES: 2 THROUGH TO AND I NCLUDI NG 27

ADVISEMENTS, OBJECTIONS & UNDERTAKINGS

*O* . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5, 6, 7, 16, 23

EXHIBITS

EXHIBIT NO. 1: Af f i davi t of Pat r i ce Bel l er ose dat ed J ul y 29, 2014

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

EXHIBIT NO. 2: Di r ect i on t o At t end dat ed August 8, 2014 . . . . . . . . 2

EXHIBIT NO. 3: At t achment t o t he emai l dat ed Mar ch 19, 2014 12: 58

PM, f r omPat r i ce Bel l er ose t o Dr . Gabor Lukacs, at t achment

121 pages. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

EXHIBIT NO. 4: Canadi an Tr anspor t at i on Agency Gener al Rul es, Rul e

No. 23. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

DATE TRANSCRI PT ORDERED: August 21, 2014

DATE TRANSCRI PT COMPLETED: August 25, 2014

171

GILLESPIEREPORTINGSERVICES,ADivisionof709387OntarioInc.,200130SlaterSt.OttawaOntarioK1P6E2

Tel:6132388501 Fax:6132381045 TollFree18002673926

2

PATRICE BELLEROSE, SWORN: 1

CROSS-EXAMINATION BY DR. GABOR LUKACS: 2

1. Q. Ms. Bel l er ose, I under st and t hat on J ul y 29, 3

2014, you swor e an af f i davi t . 4

A. Yes. 5

DR. LUKACS: Let s mar k t hat Af f i davi t as Exhi bi t 6

1. 7

EXHIBIT NO. 1: Af f i davi t of Pat r i ce Bel l er ose 8

dat ed J ul y 29, 2014 9

DR. LUKACS: 10

2. Q. And I under st and t hat you r ecei ved t he 11

Di r ect i on t o At t end dat ed August 8, 2014. 12

A. That i s cor r ect . 13

DR. LUKACS: Let s mar k i t as Exhi bi t 2. 14

EXHIBIT NO. 2: Di r ect i on t o At t end dat ed August 8, 15

2014 16

DR. LUKACS: 17

3. Q. For how l ong have you been wor ki ng wi t h t he 18

Canadi an Tr anspor t at i on Agency and i n what r ol es? 19

A. I have been wor ki ng wi t h t he Canadi an 20

Tr anspor t at i on Agency f or j ust about si x year s and my 21

i ni t i al posi t i on was t he manager of r ecor d ser vi ces and 22

access t o i nf or mat i on and pr i vacy co- or di nat or f or t he 23

Agency i ni t i al l y f or t he f i r st one t o t wo year s. I was 24

t he act i ng di r ect or of t he i nf or mat i on ser vi ces 25

172

GILLESPIEREPORTINGSERVICES,ADivisionof709387OntarioInc.,200130SlaterSt.OttawaOntarioK1P6E2

Tel:6132388501 Fax:6132381045 TollFree18002673926

3

di r ect or at e f or t hr ee and a hal f year s and I have r ecent l y 1

been changed t o a sl i ght l y di f f er ent posi t i on as t he 2

seni or manager of i nf or mat i on ser vi ces but t hat agai n i s 3

supposed t o be changi ng shor t l y. Ther e i s goi ng t o be 4

anot her r eor gani zat i on of t he Agency. 5

4. Q. I n your cur r ent r ol e what ar e your 6

r esponsi bi l i t i es? 7

A. I amr esponsi bl e f or al l r ecor ds, r ecor d 8

keepi ng at t he Agency, r et ent i on, di sposi t i ons, keepi ng 9

t he f i l es, so i nf or mat i on management , access t o 10

i nf or mat i on and mai l ser vi ces. 11

5. Q. So when you say r ecor ds can you el abor at e 12

what you mean by r ecor ds i n t hat cont ext ? 13

A. Al l r ecor ds r el at i ng t o t he Agency, bot h 14

t r ansi t or y and of f i ci al r ecor ds. 15

6. Q. So f or exampl e, when t he Agency or der s paper 16

woul d t hat al so be a r ecor d t hat you woul d be handl i ng? 17

A. I f we - - t he or der f or t he paper ? 18

7. Q. Yes, t he i nvoi ce and al l t hose t hi ngs, ar e 19

t hose r ecor ds i n t hi s sense? 20

A. I t depends. Pr obabl y f or a per i od of t i me we 21

have t o have a r ecor d of an i nvoi ce, sur e. 22

8. Q. And al so submi ssi ons of par t i es and 23

pr oceedi ngs bef or e t he Agency ar e r ecor ds? 24

A. Case f i l es ar e r ecor ds of t he Agency, yes. 25

173

GILLESPIEREPORTINGSERVICES,ADivisionof709387OntarioInc.,200130SlaterSt.OttawaOntarioK1P6E2

Tel:6132388501 Fax:6132381045 TollFree18002673926

4

9. Q. Okay. I n your cur r ent posi t i on can you 1

descr i be t o me t he chai n of command, who i s your i mmedi at e 2

super vi sor , super i or or whomdo you r epor t ? 3

A. Ri ght now I r epor t t o t he di r ect or of 4

i nf or mat i on ser vi ces who t he cur r ent act i ng i s Chr i st i ne 5

Gur et t e. She r epor t s t o t he act i ng di r ect or of 6

communi cat i ons and i nf or mat i on ser vi ces br anch whi ch i s 7

J acquel i ne Banni st er who r epor t s di r ect l y t o t he chai r man. 8

10. Q. J ust t o conf i r m, ar e you cur r ent l y or have you 9

ever been a member of t he Canadi an Tr anspor t at i on Agency? 10

A. Of t he whi ch? 11

11. Q. Of t he Canadi an Tr anspor t at i on Agency. Have 12

you been a member ? 13

A. No. 14

12. Q. I n car r yi ng out your dut i es as manager of 15

r ecor d ser vi ces and access t o i nf or mat i on and pr i vacy ar e 16

you r equi r ed t o f ol l ow t he deci si ons, r ul es and pol i ci es 17

made by t he Agency? 18

A. Yes. 19

13. Q. Now l et s l ook at Exhi bi t A t o your Af f i davi t . 20

Do you have i t i n f r ont of you? 21

A. Exhi bi t A t o my Af f i davi t ? 22

14. Q. Yes. 23

A. Yes. 24

15. Q. Thi s i s an emai l dat ed Febr uar y 14t h, 2014 25

174

GILLESPIEREPORTINGSERVICES,ADivisionof709387OntarioInc.,200130SlaterSt.OttawaOntarioK1P6E2

Tel:6132388501 Fax:6132381045 TollFree18002673926

5

f r ommysel f t o t he secr et ar y of t he Agency, cor r ect ? 1

A. Yes. 2

16. Q. Wer e you awar e when you r ecei ved t hi s t hat i t 3

expl i ci t l y makes r ef er ence t o t he f act t hat t he r equest i s 4

made pur suant t o sect i on 2( b) of t he Char t er ? 5

A. Yes. 6

17. Q. Di d you under st and t he meani ng of a r equest 7

pur suant t o sect i on 2( b) of t he Char t er ? 8

A. Yes. 9

18. Q. What does i t mean? 10

A. I t means t hat you wer e maki ng a r equest under 11

t he Char t er , under your Char t er r i ght s, and any r equest s 12

f or i nf or mat i on at t he Agency ar e t r eat ed as i n - - t hose 13

t ypes of r equest s ar e t r eat ed as i nf or mal r equest s f or 14

i nf or mat i on. 15

19. Q. What does sect i on 2( b) of t he Char t er mean t o 16

you? 17

MR. LESSARD: For t he r ecor d, I wi l l obj ect t o t he 18

quest i on because - - wel l t her e i s an i ssue of r el evance 19

but al so because you ar e aski ng t he opi ni on t o t he 20

wi t ness. However MadamBel l er ose wi l l answer subj ect t o 21

t he r i ght t o have t he pr opr i et y of t he quest i on det er mi ned 22

by t he cour t at a l at er dat e. *O* 23

DR. LUKACS: Sur e. 24

THE WI TNESS: Okay so my under st andi ng i s t hat you 25

175

GILLESPIEREPORTINGSERVICES,ADivisionof709387OntarioInc.,200130SlaterSt.OttawaOntarioK1P6E2

Tel:6132388501 Fax:6132381045 TollFree18002673926

6

wer e maki ng a r equest under t he Char t er whi ch you wer e 1

sayi ng your Char t er r i ght s al l owed you t o r equest t he 2

document s as t hey wer e par t of t he open cour t pr i nci pl e 3

and wer e subj ect - - i t was under your Char t er r i ght s as 4

opposed t o maki ng a f or mal access t o i nf or mat i on r equest . 5

DR. LUKACS: 6

20. Q. Di d you make any i nqui r y t o anybody at t he 7

Agency as t o t he meani ng of a r equest pur suant t o sect i on 8

2( b) of t he Char t er ? 9

A. Wel l , we di scussed your r equest wi t h t he 10

secr et ar y and l egal ser vi ces. 11

MR. LESSARD: I wi l l obj ect because i t i s 12

sol i ci t or / cl i ent pr i vi l ege wi t h r espect t o di scussi ons 13

wi t h l egal ser vi ces and - - l i ke f or t he r est of t he 14

quest i on I don t r eal l y have a pr obl emwi t h i t . *O* 15

THE WI TNESS: So we di scussed t he r equest and i t 16

was det er mi ned t hat we woul d pr oceed, even t hough you had 17

i ndi cat ed t hat i t was under sect i on 2( b) of t he Char t er , 18

t hat we woul d pr oceed as a nor mal r equest f or i nf or mat i on 19

as we nor mal l y r ecei ve f or ot her case f i l es t hr oughout t he 20

Agency. We r egul ar l y r ecei ve t hemf r omot her appl i cant s 21

on a dai l y basi s. 22

DR. LUKACS: 23

21. Q. Di d you r ecei ve any i nst r uct i ons f r omyour 24

super i or s about how t o pr ocess such a r equest pur suant t o 25

176

GILLESPIEREPORTINGSERVICES,ADivisionof709387OntarioInc.,200130SlaterSt.OttawaOntarioK1P6E2

Tel:6132388501 Fax:6132381045 TollFree18002673926

7

sect i on 2( b) of t he Char t er ? 1

A. Al l r equest s f or i nf or mat i on ar e pr ocessed 2

t hr ough our of f i ce i n a st andar d f ashi on; ei t her t hey ar e 3

f or mal r equest s under t he Access t o I nf or mat i on Act or 4

t hey ar e i nf or mal . Gener al l y anybody aski ng f or 5

i nf or mat i on r egar di ng a case f i l e t hat i s ongoi ng at t he 6

Agency i s consi der ed an i nf or mal r equest because t he 7

document s ar e par t of t he publ i c r ecor d. 8

22. Q. So do you agr ee wi t h me t hat Exhi bi t A t o your 9

Af f i davi t was not a r equest made pur suant t o t he Access t o 10

I nf or mat i on Act ? 11

MR. LESSARD: I wi l l obj ect f or t he r ecor d agai n 12

because i n t hi s case i t i s not appr opr i at e i n t hi s t ype of 13

exami nat i on t o ask f or admi ssi ons f r oma wi t ness. She i s 14

her e as a wi t ness and not as a par t y. However Madame 15

Bel l er ose wi l l answer subj ect t o t he r i ght t o have t he 16

pr opr i et y of t he quest i on det er mi ned by t he cour t at a 17

l at er dat e. *O* 18

THE WI TNESS: I t was not consi der ed a f or mal 19

r equest under t he Access t o I nf or mat i on Act , no. I t di d 20

not meet t he r equi r ement s. 21

DR. LUKACS: 22

23. Q. So at sect i on 3 of your af f i davi t you say t hat 23

t he r equest was t r eat ed as an i nf or mal access r equest . 24

A. Yes. 25

177

GILLESPIEREPORTINGSERVICES,ADivisionof709387OntarioInc.,200130SlaterSt.OttawaOntarioK1P6E2

Tel:6132388501 Fax:6132381045 TollFree18002673926

8

24. Q. Can you pl ease expl ai n exact l y what an 1

i nf or mal access r equest means? 2

A. I t means any r equest s f or gover nment r ecor ds 3

t hat ar e not compl et ed f or mal l y under t he Access t o 4

I nf or mat i on Act , meani ng i t must r equi r e t he $5 f ee. I t 5

must have t he f or mal f or mt hat has been compl et ed and 6

si gned. 7

25. Q. So i n t he case of t hi s r equest you d agr ee 8

t hat no f ee was pai d. 9

A. No f ee was pai d nor was t he f or mf i l l ed out . 10

26. Q. So t her e ar e t wo t ypes of r equest s. Ther e i s 11

a f or mal r equest wher e t he f ee i s pai d and t he f or mi s 12

compl et ed and - - 13

A. Cor r ect . 14

27. Q. - - t hose ar e t r eat ed as f or mal r equest s under 15

t he Act . 16

A. Cor r ect . 17

28. Q. And t hen t her e ar e t he i nf or mal r equest s whi ch 18

ar e ever yt hi ng el se whi ch ar e not t r eat ed under t he Act , 19

cor r ect ? 20

A. That ' s cor r ect . 21

29. Q. I n par agr aph 3 of your Af f i davi t you say t hat 22

t hi s r equest was t r eat ed and I amquot i ng, i n conf or mi t y 23

wi t h t he di r ect i ve on t he admi ni st r at i on of t he Access t o 24

I nf or mat i on Act . 25

178

GILLESPIEREPORTINGSERVICES,ADivisionof709387OntarioInc.,200130SlaterSt.OttawaOntarioK1P6E2

Tel:6132388501 Fax:6132381045 TollFree18002673926

9

A. Yes. 1

30. Q. I s Exhi bi t B t o your Af f i davi t t he di r ect i ve 2

t hat you ar e r ef er r i ng t o? 3

A. Yes. 4

31. Q. Can you poi nt t o speci f i c pr ovi si ons of t he 5

di r ect i ve t o whi ch t r eat i ng t he r equest as an i nf or mal 6

access r equest conf or ms? 7

A. Sect i on 7. 4. 5. 8

32. Q. Woul d you mi nd r eadi ng i t i nt o t he r ecor d j ust 9

f or cl ar i t y? 10

A. I nf or mal pr ocessi ng 11

7. 4. 5 Det er mi ni ng whet her i t i s appr opr i at e t o 12

pr ocess t he r equest on an i nf or mal basi s. I f so, 13

of f er i ng t he r equest er t he possi bi l i t y of t r eat i ng 14

t he r equest i nf or mal l y and expl ai ni ng t hat onl y 15

f or mal r equest s ar e subj ect t o pr ovi si ons of t he 16

Act . 17

33. Q. So j ust f or cl ar i t y, accor di ng t o t hi s 18

di r ect i ve an i nf or mal r equest f or access i s not subj ect t o 19

t he pr ovi si ons of t he Act . I s t hat cor r ect ? 20

A. An i nf or mal ? 21

34. Q. Yes. 22

A. That i s cor r ect . 23

35. Q. And di d you consul t t hi s di r ect i ve when you 24

wer e deci di ng how t o t r eat my r equest ? 25

179

GILLESPIEREPORTINGSERVICES,ADivisionof709387OntarioInc.,200130SlaterSt.OttawaOntarioK1P6E2

Tel:6132388501 Fax:6132381045 TollFree18002673926

10

A. No, because any r equest t hat we r ecei ve f or 1

i nf or mat i on at t he Agency ot her t han f or mal r equest s ar e 2

t r eat ed as i nf or mal access t o i nf or mat i on r equest s. 3

36. Q. Let s move on. I asked you t o br i ng t he 4

at t achment t o your Mar ch 19, 2014 emai l whi ch was 5

r ef er enced i n par agr aph 4 of your Af f i davi t . 6

A. Yes. 7

37. Q. I bel i eve i t consi st s of 121 pages. 8

A. That i s cor r ect . 9

DR. LUKACS: Let s mar k i t as Exhi bi t 3. 10

EXHIBIT NO. 3: At t achment t o t he emai l dat ed Mar ch 11

19, 2014 12: 58 PM, f r omPat r i ce Bel l er ose t o Dr . 12

Gabor Lukacs, at t achment 121 pages. 13

DR. LUKACS: 14

38. Q. Do you agr ee t hat t he f i l e cont ai ns no cl ai m 15

f or conf i dent i al i t y by any of t he par t i es? 16

A. Yes. 17

39. Q. Do you agr ee t hat t he f i l e cont ai ns no 18

det er mi nat i on by t he Agency concer ni ng conf i dent i al 19

t r eat ment of any of t he document s or por t i ons of document s 20

i n t he f i l e? 21

A. Sor r y. Can you r epeat t hat ? 22

40. Q. Do you agr ee t hat t he f i l e cont ai ns no 23

det er mi nat i on by t he Agency concer ni ng conf i dent i al 24

t r eat ment of any of t he document s or por t i ons of 25

180

GILLESPIEREPORTINGSERVICES,ADivisionof709387OntarioInc.,200130SlaterSt.OttawaOntarioK1P6E2

Tel:6132388501 Fax:6132381045 TollFree18002673926

11

document s? 1

A. No. 2

41. Q. You don t agr ee or . . . ? 3

A. No. Ther e i s per sonal i nf or mat i on t hat i s 4

cont ai ned i n t he document s t hat t he Agency det er mi nes as 5

conf i dent i al . 6

42. Q. Can you r ef er me t o - - My quest i on i s: I s 7

t her e - - i n t he f i l e i s t her e a deci si on, or der or any 8

ot her deci si on by t he Agency st at i ng t hat cer t ai n 9

document s or por t i ons of document wi l l be t r eat ed 10

conf i dent i al l y? 11

A. The Pr i vacy Act r equi r es t hat we r emove 12

per sonal i nf or mat i on f r omAgency r ecor ds. 13

43. Q. I amsor r y. I di dn t ask you about t he 14

Pr i vacy Act . I asked you about t hose 121 pages. 15

A. Yes t her e cont ai ns per sonal i nf or mat i on i n 16

t hose 121 pages. 17

44. Q. That i s not my quest i on. 18

MR. LESSARD: Can you pl ease r ef or mul at e Dr . 19

Lukacs? 20

DR. LUKACS: Sur e. 21

45. Q. Among t hose 121 pages i s t her e any document , 22

any di r ect i ve, deci si on, or der made by a member or member s 23

of t he Agency di r ect i ng t hat any of t hese document s be 24

t r eat ed conf i dent i al l y? 25

181

GILLESPIEREPORTINGSERVICES,ADivisionof709387OntarioInc.,200130SlaterSt.OttawaOntarioK1P6E2

Tel:6132388501 Fax:6132381045 TollFree18002673926

12

A. No. 1

46. Q. Thank you. Do you agr ee wi t h me t hat some of 2

t he pages wer e par t i al l y bl acked out ? 3

A. Yes. 4

47. Q. Who deci ded whi ch par t s t o bl ack out ? 5

A. Mysel f i n col l abor at i on wi t h var i ous st af f 6

member s of t he Agency. 7

48. Q. How was i t deci ded whi ch par t s t o bl ack out ? 8

A. Per sonal i nf or mat i on was r emoved. That ' s al l . 9

49. Q. Al l per sonal i nf or mat i on? 10

A. No, onl y per sonal i nf or mat i on t hat was not 11

di vul ged i n t he deci si on. 12

50. Q. Under what l egal aut hor i t y was t he bl ackened 13

out s per f or med? 14