Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lim, Day, Casey - Social Cognitive Processing in Violent Male Offenders

Uploaded by

Carousel ConfessionsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lim, Day, Casey - Social Cognitive Processing in Violent Male Offenders

Uploaded by

Carousel ConfessionsCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [University of Leicester]

On: 25 March 2012, At: 10:54

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Psychiatry, Psychology and Law

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tppl20

Social Cognitive Processing in Violent

Male Offenders

a

Loraine Lim , Assoc. Professor Andrew Day & Sharon Casey

a

School of Psychology, Deakin University, Australia

Available online: 11 Jun 2010

To cite this article: Loraine Lim, Assoc. Professor Andrew Day & Sharon Casey (2011): Social

Cognitive Processing in Violent Male Offenders, Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 18:2, 177-189

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13218711003739490

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-andconditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation

that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any

instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary

sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,

demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or

indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Psychiatry, Psychology and Law

Vol. 18, No. 2, May 2011, 177189

Social Cognitive Processing in Violent Male Oenders

Loraine Lim, Andrew Day and Sharon Casey

Downloaded by [University of Leicester] at 10:54 25 March 2012

School of Psychology, Deakin University, Australia

Social cognitive processing decits are widely believed to play a central causal role in

aggressive behaviour. In this study 76 adult male prisoners (38 violent, 38 non-violent)

were presented with a video scenario depicting an interpersonal provocation and asked

to rate their experience of anger and the likelihood of them acting aggressively in

response to the provocation. It was hypothesized that violent oenders would predict

that they would be more likely to act aggressively, feel higher levels of anger, and report

hostile attributions following an interpersonal provocation than non-violent oenders,

but that hostile attributions would be associated with aggression only in those who

scored higher on a measure of trait anger. While the results indicated that violent

oenders reported signicantly higher levels of trait anger and an increased tendency for

hostile attributions than their non-violent counterparts, the interaction was nonsignicant. This suggests that hostile attributions may play a more important role than

trait anger in predicting future acts of aggression, and has implications for the

development of rehabilitation programmes in the treatment of anger and aggression in

oenders.

Key words: aggression; anger; attribution; cognition; oender.

During the last 15 years researchers have

consistently highlighted the important role

that attributions play in inuencing both

anger arousal and aggression (e.g., Quigley

& Tedeschi, 1996; Tiedens, 2001). Of

particular note is the nding that habitually aggressive individuals have a tendency to display a hostile attribution bias;

that is, they perceive the intentions of

others as hostile, particularly when feeling

under threat or when the situation is

ambiguous (Dodge & Crick, 1990; Dodge

& Somberg, 1987; Nasby, Hayden, &

DePaulo, 1979; Tiedens, 2001). The propensity to respond aggressively following

such appraisals appears to increase when

the individual is also high in trait anger, an

individuals general propensity to experience anger and its concomitant components over time (Bettencourt, Talley,

Benjamin, & Valentine, 2006). While different theoretical accounts consistently

identify overly hostile interpretations as

an important component of trait anger

(e.g., Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Berkowitz, 1993), there is no consensus as to how

or when this bias emerges. Moreover, given

that anger does not always lead to an

aggressive response (e.g., in the case of

anger that is overcontrolled; Gross, 1998,

Correspondence: Assoc. Professor Andrew Day, Centre for Oender Reintegration @ Deakin,

School of Psychology, Faculty of Health, Medicine, Nursing and Behavioural Sciences,

Deakin University, Geelong Waterfront Campus, Geelong, Vic. 3217, Australia.

Email: andrew.day@deakin.edu.au

ISSN 1321-8719 print/ISSN 1934-1687 online

2011 The Australian and New Zealand Association of Psychiatry, Psychology and Law

DOI: 10.1080/13218711003739490

http://www.informaworld.com

Downloaded by [University of Leicester] at 10:54 25 March 2012

178

L. Lim et al.

2001; Megargee, 1966), the possibility

exists that hostile interpretations may, in

some circumstances, be a stronger predictor of reactive aggression than trait anger.

The aim of the present study was, rst, to

undertake a preliminary examination of

the inuence of hostile interpretations (in

the form of a hostile attribution bias) on

expectations of reactive aggression in the

face of a perceived provocation and,

second, to explore whether that bias is a

stronger predictor of those expectations

than trait anger.

Prior to any consideration of the

literature in this eld, it is useful to provide

operational denitions of the various constructs under investigation and identify

several key distinctions used, in particular

those relating to anger, aggression, and

hostility. Anger is a term that is commonly

used to refer to an internal emotional

response that has typical physiological

(e.g., general sympathetic arousal), cognitive (e.g., irrational beliefs, automatic

thoughts), phenomenological (e.g., subjective awareness) and behavioural (e.g.,

facial expressions) components (Berkowitz,

1993; Kassinove & Sukhodolsky, 1995). A

further distinction can be made between

state and trait anger. According to

Spielberger (1991), state anger is an

emotional state marked by subjective feelings that vary in intensity from mild

annoyance or irritation to intense fury

and rage (p. 1) whereas trait anger

involves stable individual dierences in

the frequency, duration, and intensity of

state anger (Deenbacher, 1992; Spielberger, 1991). Aggression, in contrast, is

behavioural in nature and dened in terms

of an intention to either physically or

psychologically harm someone or to destroy objects in the environment (Howells,

Daern, & Day, 2008). A distinction can

also be made between aggressive behaviour

in response to feelings of anger (variously

described as aective, hostile or reactive

aggression) and that used in the pursuit of

some goal other than victim harm (referred

to as either instrumental or proactive;

McEllistrem, 2004). Finally, hostility is

generally considered to be cognitive in

nature and incorporates the constructs of

cynicism (i.e., believing others are selshly

motivated), mistrust (i.e., an overgeneralization that others are either hurtful or

intentionally provoking), and denigration

(i.e., evaluating others as dishonest, mean,

and non-social) (Miller, Smith, Turner,

Guijarro, & Hallet, 1996). Trait hostility

is a set of beliefs that others are the source

of frustration and aggression (Smith,

1992), and is considered a stable person

characteristic (Linden et al., 2003) that is

implicated in the faulty processing of social

information (Vranceanu, Gallo, & Bogart,

2006). Individuals who are high on trait

hostility typically exhibit a pattern of social

interaction that involves antagonistic and

aggressive behaviour that is likely to be

reciprocated by others, which, in turn,

increases the likelihood of interpersonal

conict (Vranceanu et al., 2006).

According to attribution theorists, anger and aggression are the outcome of a

specic cognitiveemotionaction sequence

whereby causal attributions about responsibility determine feelings (e.g., anger) that,

in turn, guide subsequent behaviour (e.g.,

aggression; Matthews & Norris, 2002). In

the absence of clear causal explanations,

people typically resort to the use of

schemas (Fiske, 2004), chronically accessible scripts (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Zelli,

Huesmann, & Cervone, 1995), or implicit

theories (Ward, 2000) to anticipate and

predict the behaviour of others or their

social world as well as guide their own

behavioural responses. Although these

various cognitive structures exist largely

outside conscious awareness, however,

there is evidence that some individuals

reappraise incoming stimuli as a means

of re-construing an anger-inducing situation in less hostile terms (i.e., the angry

emotion is not consciously experienced)

Downloaded by [University of Leicester] at 10:54 25 March 2012

Social Cognition and Aggression in Oenders

(Davey, Day, & Howells, 2005; Gross,

2002).

Early work by Dodge (1980, 1986)

within a developmental social information

processing framework was the rst to show

that habitually aggressive individuals (children) are more likely than their nonaggressive peers to see others as having

hostile intentions, especially in situations of

perceived threat (see Crick & Dodge, 1994

for a review). According to this model, any

behavioural response is a function of

several sequential steps of processing:

accurate encoding; accurate representation

of the encoded information; specication

of an interaction goal; generation of

response alternatives; evaluation of response alternatives; and enactment of the

selected response (Dodge, Pettit, McClaskey, & Brown, 1986). Biased or decient

processing at any stage can lead to deviant,

even aggressive, behaviour.

The hostile attribution bias phenomenon, rst postulated by Nasby et al. (1979)

to explain the responses of aggressive,

emotionally disturbed boys in residential

treatment has since been replicated in a

number of studies including aggressive

boys referred to an outpatient clinic

(Milich & Dodge, 1984), socially maladjusted boys and girls (Aydin & Markova,

1979), adolescent boys and girls (Dodge &

Tomlin, 1987), middle-school-aged children (Sancilio, Plumert, & Hartup, 1989)

as well as real settings in response to

provocation (Steinberg & Dodge, 1982).

In a recent meta-analysis Orobio de Castro, Veerman, Koops, Bosch, and Monshouwer (2002) conrmed the highly

signicant association between hostile attribution of intent and aggressive behaviour, with the eects in 37 of 41 studies

reviewed being in the hypothesized direction (eect sizes ranged from r .29 to

r .65; weighted mean eect r .17). Of

greater interest to the present study is the

relation of this bias to aggression that is

reactive (i.e., aggression as a consequence

179

of anger) rather than proactive (i.e.,

aggression to aid in goal pursuit; Dodge

& Crick, 1990; Dodge & Coie, 1987).

While evidence for the hostile attribution bias has predominantly been replicated in studies involving children, there is

a body of research (albeit somewhat

smaller) that has examined whether the

eect also occurs in adults (e.g., Copello &

Tata, 1990; Epps & Kendall, 1995; Vitale,

Newman, Serin, & Bolt, 2005). In one such

study, Epps and Kendall exposed a group

of undergraduate students to a series of

scenarios that depicted benign, aggressive,

and ambiguous scenes for the purposes of

testing the discriminant validity of the

hostile attribution bias as a cognitive

correlate of anger/aggression. Discriminant

validity of the construct was supported.

Participants who scored higher on a range

of self-reported measures of anger and

aggression not only interpreted non-ambiguous stimuli as signicantly more hostile,

but were signicantly more likely to

attribute hostility to the actions of another

in the absence of sucient evidence for the

objective quantication of that hostility

(i.e., engaged in a hostile attribution bias).

Evidence for the hostile attribution bias

has also been found in oender populations. For example, Copello and Tata

(1990) showed two groups of aggressive

oenders (violent and non-violent) and a

control group (non-aggressive hospital

workers) ambiguously hostile sentences

(e.g., the painter drew the knife). At a

later stage, all participants were given new

versions of the sentences that were either

hostile (e.g., the painter pulled out the

knife) or non-hostile (e.g., the painter

sketched the knife) and asked to rate the

similarity in meaning of the new sentences

to the original. Both oender groups were

more likely than controls to report that

hostile versions of the sentences were more

similar. More recently, Vitale et al. (2005)

tested the possibility of two pathways

for hostile attributions: one related to

Downloaded by [University of Leicester] at 10:54 25 March 2012

180

L. Lim et al.

psychopathy (assessed via the Psychopathy

ChecklistRevised) (Hare, 1991) and the

other to a depressogenic attributional

style (measured with the Inferential

Styles of Questionnaire) (Rose, Abramson,

Hodluck, & Halberstadt, 1994). While

results supported the existence of two

distinct pathways, depressogenic attributional style was found to be inuential only

in the case of African American oenders.

According to the authors, the depressogenic pathway represents a tendency for

individuals to make more broad-based

negative attributions (i.e., which include

the self, others, and the world). By

comparison, the second pathway was said

to be unrelated to this broad attributional

style, associated instead with the personality construct of psychopathy. Because

psychopathy is, in part, dened by hostile,

callous and self-serving attitudes towards

others, the authors suggested that the

hostile attributions made by these individuals were a reection of their underlying

personality characteristics.

A consistent theme in the research

reviewed herein is that the association

between the biased interpretation of social

information and individual dierences in

aggressive outcomes appear to be directly

linked to individual dierences in anger

(Cohen, Eckhardt, & Schagat, 1998; Tiedens, 2001). Support for this proposition

comes via three sources of empirical ndings. First, there is the evidence of a direct

link between hostile interpretations and

trait anger (e.g., Epps & Kendall, 1995;

Wingrove & Bond, 2005); second, research

has repeatedly shown an association between reactive but not proactive aggression

and the hostile attribution bias (e.g., Crick

& Dodge, 1996; Dodge & Coie, 1987); and,

third, anger has been found to mediate the

link between interpretational biases and

aggression (Graham, Hudley, & Williams,

1992). Based on this body of evidence,

Wilkowski and Robinson (2008) have used

a dual-process model of attribution (Trope,

1996) to conclude that a trait-linked hostile

interpretation bias relies on automatic

inference processes. If this assumption is

correct, then it may be possible to correct

such biases. For example, more careful and

prolonged processing of information has

been shown to eliminate hostile interpretations (Dodge & Newman, 1981), as does

thinking about situations from a more

objective, third-person perspective (Dodge

& Frame, 1982; Sancilio et al., 1989).

Despite ample support for an association between hostility and anger or aggression, there is a dearth of published research

examining hostile attributions in people

known to have acted violently (one notable

exception is the Copello & Tata 1990 study

described above). Moreover, where an

oender population has been the focus of

study, the goal has typically been to

dierentiate between psychopathic and

non-psychopathic individuals in terms of

hostile inferences and subsequent attributions, rather than establishing whether

hostility is related to acts of violence

(Bettman, Yazar, & Rove, 1998; Serin,

1991; Vitale et al., 2005). Violent oenders

who score high on measures of psychopathy are a unique subgroup in the prison

population, and not likely to be representative of all violent oenders. There is

evidence, for example, that psychopathic

individuals can engage in aggressive acts in

the absence of anger (e.g., Serin, 1991;

Vitale et al., 2005). Consequently, the

ndings from studies involving this group

may not be generalizable across the whole

violent oender population.

A predisposition towards anger is

associated with many forms of interpersonal violence and serious violent oending

(e.g., Howells, 2004; Knight & Prentky,

1990; Kroner, Reddon, & Serin, 1992).

Individuals who are high in trait anger are

also more likely to make hostile attributions for behaviour that they experience as

provocative, which leads to higher levels of

anger arousal and, ultimately, increases the

Downloaded by [University of Leicester] at 10:54 25 March 2012

Social Cognition and Aggression in Oenders

risk of aggressive behaviour (Bettancourt

& Blair, 1992). Yet despite this wellestablished link, there has been little consideration of the role of hostile attributions

and the aggressive tendencies of violent

oenders. The aim of this study is to

redress this shortcoming by investigating

the association between hostile attributions, trait anger, and the self-reported

intent of violent oenders to act aggressively in response to an ambiguous everyday social situation. Based on the

preceding review of the literature, it is

hypothesized that violent oenders will not

only score higher on measures of trait

anger, but that they will also score higher

on levels of state anger, be more likely to

display evidence of a hostile attribution

bias, and report a greater likelihood that

they would act aggressively following an

interpersonal provocation than their nonviolent counterparts.

As previously noted, it is possible for

some individuals to behave aggressively in

the absence of anger (most notably psychopaths, although this tendency has also

been found in children; Crick & Dodge,

1996). For this reason, the present study

will also examine whether it is hostile

attributions rather than trait anger per se

that more strongly predicts the perceived

likelihood that an individual will respond

aggressively when provoked. The second

hypothesis, therefore, is that measures of

hostile attribution will be a stronger predictor of the self-reported intent to act

aggressively in response to provocation

than will trait anger. Finally, it may be

that hostile attributions are associated with

aggression only in those individuals who

have a greater general propensity for anger

arousal, namely those who are higher in

trait anger. If this is true, it may suggest

that interventions that aim to reduce the

risk of violent behaviour through changing

the attributions that individuals make for

the behaviour of others would be more

successful if targeted at those individuals

181

with high levels of trait anger, rather than

at all violent oenders. Thus, the third

hypothesis in this study is that the interaction between trait anger and hostile attributions will be a stronger predictor of a

likely aggressive response than either trait

anger or hostile attribution alone.

Method

Participants

A total of 92 randomly selected convicted

male prisoners in two correctional institutions in Singapore prisons who met the

criteria for entry into an oence-related

rehabilitation programme were invited to

take part in the study. All oenders were of

at least a high moderate level of risk for reoending. Of those approached by the

rst-named researcher, 78 oenders aged

between 18 and 57 years (M 34.29 years,

SD 1.19) agreed to participate. Subsequent data screening for missing data and

incorrect data entry indicated two outliers

that were removed from the sample, leaving a nal sample size of 76 with equal

numbers of violent and non-violent oenders in each group (N 38).

All the oenders, who came from a

range of cultural backgrounds (including

Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Eurasian),

had the requisite level of spoken and

written English to complete the questionnaires. The sample consisted of mainly

long-term prisoners (average sentence

length 6 years 9 months, SD 4.13

years), who had been incarcerated for

some time (average length of time in

prison 3 years 2 months, SD 2.47

years). Participants were classied as either

violent (N 40) or non-violent (N 38)

based on the main (index) charge that led

to their conviction. Violent crimes were

dened as including crimes such as murder,

assault, robbery, and use of weapons

(categorized as violence without bodily

harm, violence with bodily harm, grievous

bodily harm, and injuries causing death).

182

L. Lim et al.

Non-violent crimes were those that were

either non-interpersonal or did not involve

aggression (e.g., fraud, drug oences,

theft, obstructing justice, and motor

oences).

Downloaded by [University of Leicester] at 10:54 25 March 2012

Materials and Measures

Vignette

An interpersonal provocation involving a

social transgression was presented to the

participants in the form of a 45-s video

vignette. The vignette was lmed from the

point of view of an unseen protagonist, so

that the camera serves as the eyes of the

participant. It depicted the protagonist

waiting for a car to leave a parking space,

which is subsequently abruptly occupied by

another driver. In light of research suggesting that individual dierences in anger

arousal are more pronounced under conditions of ambiguity (Hazebroek, Howells,

& Day, 1999), the provocation was lmed

in an ambiguous manner (i.e., the driver is

seen in prole and does not look directly at

the protagonist). Participants were asked

to identify with the protagonist in the

scenario. The vignette was previously

used by Hazebroek et al. but with dierent

narrators. In that study, high trait individuals were shown to attribute more blame

to the antagonist, more readily identied

another as the antagonist, more readily

identied circumstances as being of relevance to their own interests, and responded

more angrily to the same events than did

individuals with low trait anger.

Likelihood of Reactive Aggression

The self-reported likelihood of engaging in

reactive aggression (aggression expectancy)

was measured with three single self-report

item questions asking each participant to

rate the likelihood that he would shout at

the driver, hit the driver, and swear at

the driver of the van on a 5-point Likert

scale from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very

likely). Scores on all of these items were

combined into a total score, with higher

scores indicating a greater self-reported

likelihood that the person would react

aggressively to perceived provocation.

While internal consistency reliability on

this measure was low (Cronbachs

a .43), given that the scale consisted of

only three items and had high face validity,

it was considered suitable for the purposes

of analysis.

StateTrait Anger Expression Inventory 2

This is a 57-item inventory that measures

the intensity of anger as an emotional state

(State Anger) and the disposition to

experience angry feelings as a personality

trait (Trait Anger) (Spielberger, 1999). The

State Anger scale was used to measure

anger arousal and included items such as I

am furious, and I feel screaming, rated

on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from

1 (not at all), to 4 (very much so). The 10item Trait Anger scale, which consists of

items such as I am quick tempered and

When I get frustrated, I feel like hitting

someone, is also rated on a 4-point Likert

type scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to

4 (almost always). Higher scores on the

trait anger scale indicate that an individual

has a greater predisposition towards anger.

Spielberger has reported internal consistency reliability (Cronbachs a) for the total

scale as ranging from .73 to .95 and from

.73 to .93 for the subscales (State and Trait

scales reported as ranging from .84 to .93).

Internal consistency reliability in the present study was moderate, with all subscales

exceeding .71.

Hostile Interpretations Questionnaire

The Hostile Interpretations Questionnaire

(HIQ) Simourd & Mamuza, 2000, 2002) is

a vignette-style inventory based on the

hostile attribution bias (Nasby et al.,

1979). The HIQ is designed to assess (a)

Downloaded by [University of Leicester] at 10:54 25 March 2012

Social Cognition and Aggression in Oenders

an individuals overall level of self-reported

hostility and (b) self-reported hostility

within several social contexts. The 35-item

self-report measure consists of seven vignettes representing a broad range of common social situations (e.g., Fred invites a

few friends to his house, and when he

walked in, his common-law wife complains

about how late he is). There are ve

questions for each vignette (e.g., How

likely do you think it is that his wife always

nags Fred), each of which is scored on a 5point Likert-type scale. Item scores are

aggregated such that there is an overall

measure of hostility, a measure of hostility

for each social situation, and measures of

dierent components of hostility. Social

situations (i.e., sources of hostility) include

authority relationships, intimate/family relationships, acquaintance relationships,

work relationships, and anonymous

relationships. Based on an individuals

responses to the vignettes, four subcomponents of hostility are then computed:

Overgeneralization (pervasive hostility

based on limited information), Attribution

of Hostility (hostility attributed to others),

Hostile Reaction (likelihood of responding

in a hostile manner), and External Blame

(degree of blame toward others for own

hostility) by summing scores on the

constituent components. Higher scores

indicate a greater propensity for hostility.

Validation studies have shown that the

measure has moderately high internal

consistency reliability (Cronbachs a

.86; Simourd & Mamuza, 2000). Internal

consistency reliability in the present study

was moderate (Cronbachs a .76). The

moderate correlations between the HIQ

and other anger/hostility measures (Aggression Questionnaire [AQ], Buss & Perry,

1992; Novaco Anger Scale [NAS] Novaco,

1994) are indicative of construct validity,

while low correlations with the Paulhus

Deception Scale (Paulhus, 1998) indicate

that the measures is less vulnerable to

respondent manipulations than either the

183

AQ or the NAS (Simourd & Mamuza,

2000).

Procedure

Potential participants were identied by a

prison sta member and asked to convene

in groups at a specially allocated room in

each prison, at which time the purpose of

the search was explained and participants

were provided with written information

about the study. No incentives were oered

for participation (nor were there disincentives for non-participation). Those with

literacy problems and/or those from nonEnglish-speaking backgrounds were excluded, as were those whose violence was

predominately sexual or family orientated

(given that such oenders are widely

considered to have a unique set of needs;

Serin & Preston, 2001). Participants were

then invited to watch the video vignette and

complete the self-report measures. Instructions were given verbally throughout the

study, and assistance was given as required

to any participant who experienced diculty with either the instructions or the

questionnaire. The entire process took

approximately 45 min for each participant

and was followed by a short debrieng

session with each group of participants to

provide contact information, to address

any issues or concerns, and to clinically

monitor any potential risk of harm to other

inmates (after watching the anger-inducing

car park scenario).

Results

To test the rst hypothesis that violent

oenders would score higher on measures

of trait and state anger, interpret greater

levels of hostile intent (i.e., subscribe to a

hostile attribution bias) and report an

increased level of aggressive expectancy

following interpersonal provocation than

their non-violent counterparts, an independent samples t test was conducted (Table 1).

184

L. Lim et al.

Table 1. State Anger, Trait Anger, Hostile Attribution, and Self-Reported Likelihood of

Aggression (N 78).

VIOLENT

Item

State Anger

Trait Anger

Hostile Attributions

Aggression Expectancy

NON-VIOLENT

SD

SD

24.87

19.84

87.05

8.42

6.86

6.27

16.16

2.93

23.08

17.00

78.53

7.00

6.71

3.78

12.04

3.12

1.15

2.39*

2.61*

2.05*

.26

.55

.60

.47

Downloaded by [University of Leicester] at 10:54 25 March 2012

Note. *p 5 .05.

As predicted, signicant between-group

dierences with moderate to large eect

sizes were noted in ratings of aggressive

expectancy, trait anger, and hostile attribution bias. An examination of the mean

scores showed that violent oenders scored

higher on all three measures. No signicant

dierence was found between the two

groups on the measure of state anger (i.e.,

anger arousal).

The hypotheses that (a) measures of

hostile attribution rather than trait anger

would be a stronger predictor of aggression

expectancy to a perceived provocation, and

(b) the interaction between trait anger and

hostile attributions would be a stronger

predictor of aggression expectancy to a

perceived provocation than either trait

anger or hostile attribution alone were

examined using hierarchical regression. In

order to test the latter hypothesis, it was

rst necessary to calculate the interaction

of trait anger and hostile attributions. This

involved the scores on both measures being

centred and the interaction term calculated

by multiplying these centred scores. Correlations between all variables used in

analysis are provided in Table 2.

In testing the second and third hypotheses, the regression model was found to be

signicantly dierent from zero at the end

of each step. At Step 1, with only oence

type in the equation, R .24, Finc(1,

74) 4.26, p 5 .05; at Step 2 with the

addition of trait anger and hostile attributions, R .57, Finc(3, 72) 11.32,

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations (N 78).

VARIABLE

Aggression

Expectancy

(AE)

State Anger

(SA)

Trait Anger

(TA)

Hostile

Attribution

Bias (HAB)

Hostile

Attribution

Bias 6 Trait

Anger

(HAB 6 TA)

AE

SA

TA

HAB

.64**

.46**

.52**

.54*** .62**

.26*

.32*

.62**

.44*

Note. *p 5 .05; **p 5 .01; ***p 5 .001.

p 5 .001; and at Step 3, with all independent variables in the equation, R .57,

Finc(4, 71) 8.45, p 5 .001. The full

model accounted for 28% (R2adj .28) of

the total variance in aggression expectancy

to perceived provocation. As predicted by

the second hypothesis, hostile attribution

bias (b .39, t 3.15, p 5 .01) was a

stronger predictor of aggression expectancy than trait anger (b .19, t 1.55,

p 4 .05). The third hypothesis, that hostile

attributions would be associated with

aggression for those with higher trait anger

scores, was not supported; the addition of

the interaction term did not result in a

signicant increment in R2. The only

variable that remained signicant at Step

3 was hostile attribution bias (b .40,

185

Social Cognition and Aggression in Oenders

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression of Aggression Expectancy (N 78).

VARIABLES

Downloaded by [University of Leicester] at 10:54 25 March 2012

Step 1

Oence type

Step 2

Oence type

Trait Anger

Hostile attributions

Step 3

Oence type

Trait Anger

Hostile attributions

Trait Anger 6 Hostile Attribution

Bias interaction

.60

.23*

.23

.11

.08

.09

.19

.39**

.21

.10

.08

.002

.08

.19

.40**

.05

R2

R2adjusted

.23

.05

.04

.57

.32

.29

.57

.32

.28

R2change

.27***

Note. *p 5 .05; **p 5 .01; ***p 5 .001.

t 3.16, p 5 .01). Table 3 provides the

unstandardized regression coecients (B),

standardized regression coecients (b), R,

R2, and R2change at each stage of the

analysis.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to

investigate whether individual dierences

in cognitive processing, namely a hostile

attributional bias, could account for dierences in anger and aggressive expectancy in

response to a seemingly innocuous event, in

a sample of violent and non-violent oenders. As predicted, oenders in the sample

who had been convicted of violent crimes

were more likely than their non-violent

counterparts to indicate an intent to

respond aggressively to the targets behaviour, a nding consistent with previous

work by Hazebroek et al. (1999). Violent

oenders were also found to have higher

trait anger and were more likely to interpret the behaviour of others as having

hostile intent; in other words, they subscribed to a hostile attribution bias. While

the former is not unsurprising, given the

association between anger and interpersonal violence (e.g., Howells, 2004; Knight &

Prentky, 1990; Kroner et al., 1992),

the latter nding warrants further consideration. Given that previous research by

Copello and Tata (1990) found no dierence between violent and non-violent

oenders in the tendency to make hostile

attributions, it raises several questions. The

rst is whether the results in this study are

simply an artefact of population dierences. In the Copello and Tata study, both

groups of oenders were identied as high

on aggression (although no indication was

given on how this was established). It may

simply be that the non-violent oenders in

this study had very low levels of aggression.

An alternative, and more likely explanation, is the identied link between trait

anger and the tendency to make hostile

attributions (e.g., Epps & Kendall, 1995).

This is certainly supported by the strength

of the correlation between these two

variables. Another explanation is the lack

of signicant dierence between the two

oender groups on self-reported levels of

anger arousal (i.e., state anger). Although

this nding is consistent with previous

reports that anger arousal is neither a

necessary nor sucient condition for aggression in many violent oenders (e.g.,

Zelli et al., 1995), it is highly likely that in

the absence of an attribution of hostile

intent, there is no angry response (or one

Downloaded by [University of Leicester] at 10:54 25 March 2012

186

L. Lim et al.

that is much lower in valence to that

experience by violent oenders).

In terms of the relative contribution of

trait anger and hostile intent to the

prediction of future aggressive behaviour,

ndings from the regression analysis provided support for the second hypothesis

but not the third. Perceptions of hostile

intent explained twice as much variance in

aggressive expectancy (39%) as compared

to that explained by trait anger (19%). This

nding not only provides further support

for the discriminant validity of the hostile

attribution bias, it also adds weight to the

dual process model of attribution (Trope,

1996). According to the model, attributions

are automatic, occurring at the very early

stages of social information, which would

lead it to take precedence over any other

processing task. One might therefore expect trait anger to be a stronger predictor

in cases where people have more time to

make a decision or are instructed to

consider the consequences of their actions.

Given the consequences of aggressive

actions, distinguishing between the two

constructs certainly warrants further investigation. Additional support for the greater

inuence of hostile intent as compared to

trait anger is evident in the failure of a

Trait Anger 6 Hostile Attribution Bias

interaction to signicantly predict the likelihood of an aggressive response. In fact,

the interaction had minimal inuence on

the prediction, while hostile intent became

marginally stronger.

While these ndings have relevance

from a theoretical perspective, the applied

implications of the results are perhaps of

greatest utility. Of particular signicance is

highlighting the need to assess for both

hostile attribution bias and trait anger

when determining the appropriateness of

a referral to a therapeutic programme

(Novaco, 1997), and that the combination

of unrealistic attributions of intent during a

provoking situation and high levels of trait

anger should both be key targets for

change in treatment for violent individuals

(Grodnitzky & Tafrate, 2000). Research

has shown that interventions designed to

reduce the hostile attribution bias are

eective in lessening tendencies toward

anger and aggression. This has been illustrated by Guerra and Slaby (1990), whose

treatment programme to correct a variety

of cognitive biases linked to aggression,

including the hostile attribution bias, was

found to successfully reduce reactive aggression in adolescents. Hudley and

Graham (1993) had similar success with a

treatment programme to reduce anger and

aggression in children. That said, some

aggressive individuals will require alternative

approaches, especially if they over-control

their anger (Davey et al., 2005), or have a

pathologically low level of arousal to interpersonal interactions, as may be the case for

those with psychopathic traits. Given that

violent oenders, however, are generally

more likely to score higher on measures of

trait anger and that trait anger appears to be

strongly associated with the tendency to

assume hostile attribution intent, this study

oers support for the delivery of cognitive

behavioural programmes that incorporate

activities that involve exposure to provocation and seek to equip violent oenders with

the skills to make non-hostile attributions for

such provocations.

The study is not without its limitations.

For example, self-report on the measure of

aggression expectancy to perceived provocation is fraught with diculty in terms of

socially desirable responding. Future research should include such a measure to

establish whether the dierences noted

in the present study between violent and

non-violent oenders are reliable. Another

consideration is the dierence between

reporting intent (i.e., aggression expectancy) and actually engaging in such

behaviour. A range of antecedent factors

inuences how people respond to provocation (ambiguous or otherwise) and a true

test of association between the hostile

Downloaded by [University of Leicester] at 10:54 25 March 2012

Social Cognition and Aggression in Oenders

attribution bias and aggressive or violent

behaviour would need to be more ecologically sound. Finally, it is possible that

other factors may have inuenced the

extent to which either anger or hostility

inuenced aggression expectancy. One such

factor is the degree to which prolonged

attention is paid to the negative information. There is evidence that individuals who

report increased tendencies toward angry

rumination demonstrate much higher levels

of trait anger (Berry, Worthington, OConnor, Parrott, & Wade, 2005; Martin &

Dahlen, 2005). These individuals have also

been found to exhibit prolonged tendencies

toward aggressive behaviour following a

provocation (Collins & Bell, 1997). The

other consideration, and one alluded to in

the introduction, is the role of eortful

control (or emotional regulation), which

has been associated with reduced trait

anger (Gross, 2002; Posner & Rothbart,

2000). Despite these limitations, the study

provides a useful rst step in understanding

the role of the hostile attribution bias in

violent oenders.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of

the Singapore Prison Service. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors

and do not necessarily reect those of the

Singapore Prison Service.

References

Anderson, C.A., & Bushman, B.J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 2751.

Aydin, O., & Markova, I. (1979). Attributional

tendencies of popular and unpopular children. British Journal of Social and Clinical

Psychology, 18, 291298.

Berkowitz, L. (1993). Aggression: Its causes,

consequences, and control. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Berry, J.W., Worthington, E.L., OConnor, L.E.,

Parrott, L., & Wade, N.G. (2005). Forgiveness, vengeful rumination, and aective traits.

Journal of Personality, 73, 183225.

187

Bettancourt, H., & Blair, I. (1992). A cognition

(attribution)-emotion model of violence in

conict situations. Personality and Social

Psychology Bulletin, 18, 343350.

Bettencourt, B.A., Talley, A., Benjamin, A.J., &

Valentine, J. (2006). Personality and aggressive behavior under provoking and neutral

conditions: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 751777.

Bettman, M.D., Yazar, R., & Rove, R. (1998).

Violence prevention program manual.

Ottawa: Correctional Service of Canada.

Buss, A.H., & Perry, M. (1992). The aggression

questionnaire. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 63, 452459.

Cohen, D., Eckhardt, C., & Schagat, K. (1998).

Attention allocation and habituation to

anger-related stimuli during a visual search

task. Aggressive Behavior 24, 399409.

Collins, K., & Bell, R. (1997). Personality and

aggression: The dissipation-rumination

scale. Personality and Individual Dierences,

22, 751755.

Copello, A.G., & Tata, P.R. (1990). Violent

behaviour and interpretative bias: An experimental study of the resolution of ambiguity in violent oenders. British Journal of

Social Psychology, 29, 417428.

Crick, N., & Dodge, K.A. (1994). A review and

reformulation of social information processing mechanisms in childrens social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 74101.

Crick, N.R., & Dodge, K.A. (1996). Social

information-processing mechanisms in reactive and proactive aggression. Child Development, 67, 9931002.

Davey, L., Day, A., & Howells, K. (2005).

Anger, over-control and serious violent

oending. Aggression and Violent Behavior

10, 624635.

Deenbacher, J.L. (1992). Trait anger: Theory,

ndings, and implications. In C.D. Spielberger, & J.N. Butcher (Eds.), Advances in

personality assessment (Vol. 9, pp. 177201).

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dodge, K.A. (1986). A social information processing model of social competence in children. In

M. Perlmutter (Ed.), The Minnesota Symposia

on Child Psychology: Vol. 18. Cognitive

Perspectives on Childrens Social and Behavioural Development (pp. 77125). Hillsdale,

NJ: Erlbaum.

Dodge, D.A., & Coie, J.D. (1987). Social

information-processing factors in reactive

and proactive aggression in childrens peer

groups. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 53, 11461158.

Downloaded by [University of Leicester] at 10:54 25 March 2012

188

L. Lim et al.

Dodge, K.A., & Crick, N.R. (1990). Social

information processing biases of aggressive

behaviour in children. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16, 822.

Dodge, D.A., & Frame, C.L. (1982). Social

cognitive biases and decits in aggressive

boys. Child Development, 53, 620635.

Dodge, D.A., & Newman, J.P. (1981). Biased

decision-making processes in aggressive boys.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 90, 375379.

Dodge, D.A., & Somberg, D.R. (1987). Hostile

attributional biases among aggressive boys

are exacerbated under conditions of threats

to self. Child Development, 583, 213224.

Dodge, D.A., & Tomlin, A. (1987). Cueutilization as a mechanism of attributional

bias in aggressive children. Social Cognition,

5, 280300.

Dodge, K.A. (1980). Social cognition and

childrens aggressive behavior. Child Development, 51, 162170.

Dodge, K.A., Pettit, G.S., McClaskey, C.L., &

Brown, M. (1986). Social competence in children. Monographs of the Society for Research in

Child Development, 51(2, Serial No. 213).

Epps, J., & Kendall, P.C. (1995). Hostile

attribution bias in adults. Cognitive Therapy

and Research, 19, 159178.

Fiske, S.T. (2004). Social beings: A core motives

approach to social psychology. Hoboken,

NJ: John Wiley.

Graham, S., Hudley, C., & Williams, E. (1992).

Attributional and emotional determinants

of aggression among African-American and

Latino young adolescents. Developmental

Psychology, 28, 731740.

Grodnitzky, G.R., & Tafrate, R.C. (2000).

Imaginal exposure for anger reduction in

adult outpatients: A pilot study. Journal of

Behaviour Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 31, 259279.

Gross, J. (1998). The emerging eld of emotion

regulation: An integrative review. Review of

General Psychology 2(3), 271299.

Gross, J. (2001). Emotion regulation in adulthood: Timing is everything. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 214219.

Gross, J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Aective,

cognitive and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39, 281291.

Guerra, N.G., & Slaby, R.G. (1990). Cognitive

mediators of aggression in adolescent oenders: II. Intervention. Developmental Psychology, 26, 269277.

Hare, R.D. (1991). Manual for the Hare

Psychopathy ChecklistRevised. Toronto:

Multi-Health Systems.

Hazebroek, J., Howells, K., & Day, A. (1999).

Cognitive appraisals associated with high

trait anger. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 3145.

Howells, K. (2004). Anger and its links to

violent oending. Psychiatry, Psychology

and Law, 11, 189196.

Howells, K., Daern, M., & Day, A. (2008).

Aggression and violence. In K. Soothill, M.

Dolan, & P. Rogers (Eds.), The handbook

of forensic mental health (pp. 351374).

Cullompton, Devon: Willan.

Hudley, S., & Graham, S. (1993). An attributional intervention to reduce peer-directed

aggression among African-American boys.

Child Development, 64, 124138.

Kassinove, H., & Sukhodolsky, D. (1995).

Anger disorders: Basic science and practice

issues. In H. Kassinove (Ed.), Anger disorders: Denition, diagnosis, and treatment

pp. l26). Washington, DC: Taylor and

Francis.

Knight, R.A., & Prentky, R.A. (1990). Classifying

sexual oenders: The development and corroboration of taxonomic models. In W.L.

Marshall, D. R. Laws, & H.E. Barbaree

(Eds.), Handbook of sexual assault: Issues,

theories, and treatment of the oender (pp. 23

52). New York: Plenum Press.

Kroner, D.G., Reddon, J.R., & Serin, R.C.

(1992). The multidimensional anger inventory: Reliability and factor structure in an

inmate sample. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52, 687693.

Linden, W., Hogan, B.E., Rutledge, T., Chawla,

A., Lenz, J.W., & Leung, D. (2003). There is

more to anger coping than in or out.

Emotion, 3, 1229.

Martin, R.C., & Dahlen, E.R. (2005). Cognitive

emotion regulation in the prediction of

depression, anxiety, stress, and anger. Personality and Individual Dierences, 39, 1249

1260.

Matthews, B.A., & Norris, F.H. (2002). When is

believing seeing? Hostile attribution bias

as a function of self-reported aggression.

Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32, 1

32.

McEllistrem, J.E. (2004). Aective and

predatory violence: A bimodal classication system of human aggression and

violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior,

10, 130.

Megargee, E. (1966). Undercontrolled and overcontrolled personality types in extreme antisocial aggression. Psychological Monographs, 80, 1611.

Downloaded by [University of Leicester] at 10:54 25 March 2012

Social Cognition and Aggression in Oenders

Milich, R., & Dodge, K.A. (1984). Social

information processing in child psychiatry

populations. Journal of Abnormal Child

Psychology, 12, 471490.

Miller, T., Smith, T.W., Turner, C.W., Guijarro, M.L., & Hallet, A.J. (1996). Metaanalytic review of research on hostility and

physical health. Psychological Bulletin, 119,

322348.

Nasby, W., Hayden, B., & DePaulo, B.M.

(1979). Attributional bias among aggressive

boys to interpret unambiguous social stimuli as hostile displays. Journal of Abnormal

Psychology, 89, 459468.

Novaco, R.W. (1994). Anger as a risk factor for

violence among the mentally disordered. In

J. Monahan & H.J. Steadman (Eds.),

Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments

in Risk Assessment (pp. 2159). Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Novaco, R.W. (1997). Remediating anger and

aggression with violent oenders. Legal and

Criminological Psychology, 2, 7788.

Orobio de Castro, B., Veerman, J.W., Koops,

W., Bosch, J.D., & Monshouwer, H.J.

(2002). Hostile attribution of intent and

aggressive behaviour: A meta-analysis.

Child Development, 73, 916934.

Paulhus, D.L. (1998). Manual for the Balanced

Inventory of Desirable Responding: Version

7. Toronto/Bualo: Multi-Health Systems.

Posner, M.I., & Rothbart, M.K. (2000). Developing mechanisms of self-regulation.

Development and Psychopathology, 12,

427441.

Quigley, B.M., & Tedeschi, J.T. (1996). Mediating eects of blame attributions on feelings

of anger. Personality and Social Psychology

Bulletin, 22, 12801288.

Rose, D.T., Abramson, L.Y., Hodluck, C.Y., &

Halberstadt, L. (1994). Heterogeneity of cognitive style among depressed inpatients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 419429.

Sancilio, M.F., Plumert, J.M., & Hartup, W.W.

(1989). Friendship and aggressiveness as

determinants of conict outcome in middle

childhood Developmental Psychology, 25,

812819.

Serin, R.C. (1991). Psychopathy and violence in

criminals. Journal of Interpersonal Violence,

6, 423431.

Serin, R.C., & Preston, D.L. (2001). Managing

and treating violent oenders. In J.B.

Ashford, B.D. Sales & W. Reid (Eds.),

Treating adult and juvenile oenders with

special needs (pp. 249271). Washington,

DC: American Psychological Association.

189

Simourd, D.J., & Mamuza, J.M. (2000). The

Hostile Attributions Questionnaire: Psychometric properties and construct validity. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 27, 645

663.

Simourd, D.J., & Mamuza, J.M. (2002). Hostile

Interpretations Questionnaire: Users manual. Kingston, Ontario: ACES.

Smith, T.W. (1992). Hostility and health: Status

of a psychometric hypothesis. Health Psychology, 11, 139150.

Spielberger, C.D. (1991). State-trait Anger

Expression Inventory Revised Research Edition, Professional Manual. Odessa, FL:

Psychological Assessment Resources.

Spielberger, C.D. (1999). State-Trait Anger

Expression Inventory-2, professional manual.

Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment

Resources.

Steinberg, M.D., & Dodge, K.A. (1982). Attributional bias in aggressive adolescent boys

and girls. Journal of Social and Clinical

Psychology, 1, 312321.

Tiedens, L.Z. (2001). The eect of anger on the

hostile inferences of aggressive and nonaggressive people: Specic emotions, cognitive

processing, and chronic accessibility. Motivation and Emotion, 25, 233251.

Trope, Y. (1996). Identication and inferential

processes in dispositional attributions. Psychological Review, 93, 239257.

Vitale, J.E., Newman, J.P., Serin, R.C., & Bolt,

D.M. (2005). Hostile attributions in incarcerated adult male oenders: An exploration of diverse pathways. Aggressive

Behavior, 31, 99115.

Vranceanu, A.M., Gallo, L.C., & Bogart, L.M.

(2006). Hostility and perceptions of support in

ambiguous social interactions. Journal of

Individual Dierences, 27, 108115.

Ward, T. (2000). Sexual oenders cognitive

distortions as implicit theories. Aggression

and Violent Behavior, 5, 491507.

Wilkowski, B.M., & Robinson, M.D. (2008). The

cognitive bias of trait anger and aggression: An

integrative analysis. Personality and Social

Psychology Review, 12, 321.

Wingrove, J., & Bond, A.J. (2005). Correlation

between trait hostility and faster reading

times for sentences describing angry reactions to ambiguous situations. Cognition

and Emotion, 19, 463472.

Zelli, A., Huesmann, L.R., & Cervone, D.

(1995). Social inference and individual

dierences in aggression: Evidence for

spontaneous judgments of hostility. Aggressive Behavior, 21, 405417.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- ADP G2 Spreadsheet Loader Data Entry: End-User GuideDocument48 pagesADP G2 Spreadsheet Loader Data Entry: End-User Guideraokumar250% (2)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Opening Checklist: Duties: Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday SundayDocument3 pagesOpening Checklist: Duties: Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday SundayAlven BlancoNo ratings yet

- Clock of Destiny Book-1Document46 pagesClock of Destiny Book-1Bass Mcm87% (15)

- (Biophysical Techniques Series) Iain D. Campbell, Raymond A. Dwek-Biological Spectroscopy - Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company (1984)Document192 pages(Biophysical Techniques Series) Iain D. Campbell, Raymond A. Dwek-Biological Spectroscopy - Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company (1984)BrunoRamosdeLima100% (1)

- Test 1801 New Holland TS100 DieselDocument5 pagesTest 1801 New Holland TS100 DieselAPENTOMOTIKI WEST GREECENo ratings yet

- Group 3 Presenta Tion: Prepared By: Queen Cayell Soyenn Gulo Roilan Jade RosasDocument12 pagesGroup 3 Presenta Tion: Prepared By: Queen Cayell Soyenn Gulo Roilan Jade RosasSeyell DumpNo ratings yet

- Narrative FixDocument6 pagesNarrative Fixfitry100% (1)

- PC300-8 New ModelDocument22 pagesPC300-8 New Modeljacklyn ade putra100% (2)

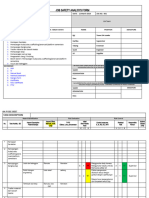

- JSA FormDocument4 pagesJSA Formfinjho839No ratings yet

- Creativity Triggers 2017Document43 pagesCreativity Triggers 2017Seth Sulman77% (13)

- Fractional Differential Equations: Bangti JinDocument377 pagesFractional Differential Equations: Bangti JinOmar GuzmanNo ratings yet

- GSM Based Prepaid Electricity System With Theft Detection Using Arduino For The Domestic UserDocument13 pagesGSM Based Prepaid Electricity System With Theft Detection Using Arduino For The Domestic UserSanatana RoutNo ratings yet

- Data Mining For Business Analyst AssignmentDocument9 pagesData Mining For Business Analyst AssignmentNageshwar SinghNo ratings yet

- Protected PCM USB Memory Sticks For Pa3X.Document1 pageProtected PCM USB Memory Sticks For Pa3X.mariuspantera100% (2)

- English 8 q3 w1 6 FinalDocument48 pagesEnglish 8 q3 w1 6 FinalJedidiah NavarreteNo ratings yet

- "Prayagraj ": Destination Visit ReportDocument5 pages"Prayagraj ": Destination Visit ReportswetaNo ratings yet

- Integrated Management System 2016Document16 pagesIntegrated Management System 2016Mohamed HamedNo ratings yet

- FBISE Grade 10 Biology Worksheet#1Document2 pagesFBISE Grade 10 Biology Worksheet#1Moaz AhmedNo ratings yet

- Duties and Responsibilities - Filipino DepartmentDocument2 pagesDuties and Responsibilities - Filipino DepartmentEder Aguirre Capangpangan100% (2)

- Marketing Plan Nokia - Advanced MarketingDocument8 pagesMarketing Plan Nokia - Advanced MarketingAnoop KeshariNo ratings yet

- Smashing HTML5 (Smashing Magazine Book Series)Document371 pagesSmashing HTML5 (Smashing Magazine Book Series)tommannanchery211No ratings yet

- Basics of Petroleum GeologyDocument23 pagesBasics of Petroleum GeologyShahnawaz MustafaNo ratings yet

- The Abcs of Edi: A Comprehensive Guide For 3Pl Warehouses: White PaperDocument12 pagesThe Abcs of Edi: A Comprehensive Guide For 3Pl Warehouses: White PaperIgor SangulinNo ratings yet

- Week1 TutorialsDocument1 pageWeek1 TutorialsAhmet Bahadır ŞimşekNo ratings yet

- CMS156Document64 pagesCMS156Andres RaymondNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography 2Document3 pagesAnnotated Bibliography 2api-458997989No ratings yet

- AJ IntroductionDocument31 pagesAJ IntroductiontrollergamehuydkNo ratings yet

- Discrete Random Variables: 4.1 Definition, Mean and VarianceDocument15 pagesDiscrete Random Variables: 4.1 Definition, Mean and VariancejordyswannNo ratings yet

- Machine Tools PDFDocument57 pagesMachine Tools PDFnikhil tiwariNo ratings yet

- Đề Anh DHBB K10 (15-16) CBNDocument17 pagesĐề Anh DHBB K10 (15-16) CBNThân Hoàng Minh0% (1)