Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Benguet Vs Republic

Uploaded by

Rose Ann CalanglangOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Benguet Vs Republic

Uploaded by

Rose Ann CalanglangCopyright:

Available Formats

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

SECOND DIVISION

G.R. No. 71412 August 15, 1986

BENGUET CONSOLIDATED, INC., (now Benguet

Corporation), petitioners,

vs.

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, respondent.

This is a petition to review the decision of the

Intermediate Appellate Court in an expropriation case,

insofar as the decision affects the petitioner.

Benguet Consolidated filed two other motions: 1. motion

for new trial and/or reconsideration; 2. motion for

clarification reiterating its objection to the decision in not

providing for just compensation for their expropriated

properties.

The trial court issued an order fixing the "just

compensation of the surface area of the four (4) claims

of Benguet Consolidated, Inc. in the amount of

P128,051.82 with interest at 6% per annum from May 6,

1950 until fully paid, plus attorney's fees in an amount

equal to 5 % of the sum fixed by this Court

Among all parties, only the plaintiff and defendant

Benguet Consolidated, Inc. pursued their appeal before

the then Court of Appeals.

CA:

FACTS:

On 1958, the Republic of the Philippines filed with the

CFI of Benguet and Baguio a complaint for expropriation

against ten (10) defendants and among them is the

Benguet Consolidated, Inc.

The Republic stated that it needed the property for the

purpose of establishing and maintaining a permanent

site for the PMA, a training institution for officers in the

AFP, under the direct authority and supervision of the

Department of National Defense.

It also averred that it had occupied since 1950, the area

covered by the mining claims of the defendants and had

already installed permanent buildings and other valuable

improvements with no less than P3,000,000.00 in the

belief that the area was unoccupied portions of the

public domain.

The petitioner filed a motion to dismiss on the ground

that the Republic did not need and has not occupied the

areas covered by the above-mentioned mining claims

and neither have improvements been made on the said

areas and that the area covers ground which is rugged

in terrain which could have no use to the PMA.

By way of separate and special grounds for dismissal,

petitioner also alleged that the authority given by the

President of the Philippines for the expropriation

proceedings refers to privately owned mineral lands,

mining interests, and other private interests of private

and that the expropriation of Benguet Consolidated,

Inc.'s mineral claims is in violation of law.

On 1985, the IAC promulgated a decision setting aside

the trial court's decision and condemn the mineral claims

belonging to the defendants for the public use and

ordering the plaintiff to pay the defendants.

The petitioner asserts that there is a need to review and

reverse the appellate court's decision because of the

following reasons:

A. THE CONDEMNATION OF PETITIONER'S

MINERAL CLAIM IS CONTRARY TO LAW AND

APPLICABLE JURISPRUDENCE.

B. THE APPROVAL OF THE COMMISSIONER'S

REPORT IS CONTRARY TO LAW AND APPLICABLE

JURISPRUDENCE.

The petitioner states that its mineral claims were located

since 1933 at the latest. It argues that by such location

and perfection, the land is segregated from the public

domain even as against the government. Citing case of

Gold Greek Mining Corporation it states that when the

location of a mining claim is perfected, this has the effect

of a grant of exclusive possession with right to the

enjoyment of the surface ground as well as of all the

minerals within the lines of the claim and that this right

may not be infringed.

ISSUE: W/N the power of the government to exercise

power of imminent domain is barred upon the perfection

of the mining claim.

HELD:

LOWER COURT:

On 1955, the trial court issued an order declaring that

the plaintiff Republic of the Philippines is hereby

declared to have lawful right to take the property sought

to be condemned, for the public upon payment of just

compensation to be determined as of the date of the

filing of the complaint.

The petitioner's arguments have no merit. The filing of

expropriation proceedings recognizes the fact that the

petitioner's property is no longer part of the public

domain. The power of eminent domain refers to the

power of government to take private property for public

use. If the mineral claims are public, there would be no

need to expropriate them. The mineral claims of the

petitioner are not being transferred to another mining

company or to a public entity interested in the claims as

such. The land where the mineral claims were located is

needed for the Philippine Military Academy, a public use

completely unrelated to mining. The fact that the location

of a mining claim has been perfected does not bar the

Government's exercise of its power of eminent domain.

The right of eminent domain covers all forms of private

property, tangible or intangible, and includes rights which

are attached to land.

The petitioner next raises a procedural point-whether or

not in expropriation proceedings an order of

condemnation may be entered by the court before a

motion to dismiss is denied. The petitioner claims that

this cannot be done.

In the instant case of Nieto, the ruling on the motion to

dismiss was deferred by the trial court in view of a

possible amicable settlement. Moreover, after the trial

court entered an order of condemnation over the

objection of the petitioner, the court issued an order to

the effect that the trial court."

At the hearing conducted by the Board of

Commissioners, the counsel for the petitioner

manifested that its motion to dismiss was still pending in

court, and requested that the hearing for the

presentation of evidence for the petitioner be cancelled.

At this point, negotiations between the government and

the petitioner were still going on.

In its original decision, the lower court overlooked an

award of just compensation for the petitioner. This

triggered off the filing of the following motions by the

petitioner: (1) motion for clarification praying that an

order be issued clarifying the decision insofar as the

compensation to be paid to the petitioner is concerned;

(2) motion for new trial and/or reconsideration on the

ground that the court did not award just compensation

for the properties of the petitioner; (3) motion to re-open

case on the ground that the issues insofar as the

petitioner is concerned have not been joined since its

motion to dismiss has not been resolved; and (4) a

second motion for clarification.

Under these circumstances, the petitioner is estopped

from questioning the proceedings of condemnation

followed by the court. We cannot condone the

inconsistent positions of the petitioner. (See Republic v.

Court of Appeals, 133 SCRA 505). it is very clear from

the statements of the petitioner that it had already

abandoned its earlier stand on the propriety of

expropriation and that its intent shifted to the just

compensation to be paid by the plaintiff for its

condemned properties.

The second issue centers on the amount of just

compensation which should be paid by the respondent

to the petitioner for the condemned properties.

The petitioner assails the appellate court's approval of

the Commissioners' Report which fixed the amount of

P7,532.46 as just compensation for the mineral claims.

The petitioner contends that this amount is by any

standard ridiculously low and cannot be considered just

and that in fact the commissioners' report was rejected

by the trial court.

The P7,532.46 just compensation for the petitioner was

based on the findings of the Board of Commissioners

which conducted an ocular inspection of the mining

claims with prior notice to all the parties.

However, the exploration and/or development work on

these claims is not sufficient for making any estimate of

the value of these claims for mining purposes. The

property has possibilities; but, with the limited work done

on these claims, no ore body has as yet been found.

Consequently, the value of these claims cannot be

determined at the present time.

The petitioner's mining claims were classified as nonproducing unpatented claims. It was established that the

area of the mineral claims belonging to the petitioner and

included in the Philippine Military Reservation was

25.1082 hectares. Hence, the commissioners arrived at

the total amount of P7,532.46 (25.1082 x P300.00) as

just compensation to be paid to the petitioner for its

mining claims.

These findings negate the trial court's observation that

the commissioners only took into consideration the

surface value of the mineral claims. In fact, the lower

court affirmed the commissioners' report to the effect

that the petitioner herein is only entitled to the surface

value of the mineral claims.

"Other claims" include the petitioner's mining claims.

Thus, the trial court computed the amount to be paid to

the petitioner as just compensation on the basis of the

surface value of its mining claims.

We find no reason to disturb the lower court's findings on

this matter. The petitioner has not advanced any reason

for us to reject such findings.

As stated earlier, the appellate court based its findings

on the Commissioners' Report. The petitioner now

assails the approval of the commissioners' report

regarding the P7,532.46 just compensation to be paid by

the government for its four (4) mining claims.

While it is true that a court may reject a Commissioners'

Report on the ground that the amount allowed is

palpably inadequate, it is to be noted that the petitioner

herein has not supported its stand that the P7,532.46

just compensation for its mining claims is by any

standard ridiculously low and cannot be considered just.

We are not inclined to reject these findings of facts of the

appellate court in the absence of any contrary evidence

pointed to by the petitioner.

Moreover, it is to be noted that unlike the plaintiff and

other defendants, the petitioner did not file any

opposition to the Commissioners' Report in the lower

court.

The appellate court, however, should have provided for

the payment of legal interest from the time the

government took over the petitioner's mining claims until

payment is made by the government.

The appellate court's decision is, therefore, modified in

this respect.

WHEREFORE, the decision of the Intermediate

Appellate Court is MODIFIED in that the government is

directed to pay the petitioner the amount of SEVEN

THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED THIRTY-TWO PESOS)

and 46/100 (P7,532.46) plus 6% interest from May 6,

1950 to July 29, 1974 and 12% thereafter until fully paid,

and AFFIRMED in all other respects.

SO ORDERED.

You might also like

- Benguet Consolidated VS. RepublicDocument3 pagesBenguet Consolidated VS. RepublicGabby ElardoNo ratings yet

- 10 Hizon Vs CADocument11 pages10 Hizon Vs CAcharmssatellNo ratings yet

- VNJDocument2 pagesVNJjulyenfortunatoNo ratings yet

- Universal Robina V LLDA - Water Pollution PDFDocument12 pagesUniversal Robina V LLDA - Water Pollution PDFkumiko sakamotoNo ratings yet

- Alaska Milk Corporation v. Ponce, July 26, 2017Document2 pagesAlaska Milk Corporation v. Ponce, July 26, 2017Allan Jay EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- Consti 2 OutlineDocument44 pagesConsti 2 OutlineGabe RuaroNo ratings yet

- BF Northwest Homeowners Association, Inc. vs. Intermediate Appellate CourtDocument9 pagesBF Northwest Homeowners Association, Inc. vs. Intermediate Appellate CourtRMC PropertyLawNo ratings yet

- Environmental CasesDocument215 pagesEnvironmental CasesKMNo ratings yet

- Moncupa Vs EnrileDocument1 pageMoncupa Vs EnrileGheeness Gerald Macadangdang MacaraigNo ratings yet

- Comilang V BuendiaDocument4 pagesComilang V BuendiaWatz RebanalNo ratings yet

- Lumiqued VS Exevea (Digest)Document1 pageLumiqued VS Exevea (Digest)Marc BuenoNo ratings yet

- Hermano Oil Vs TRBDocument2 pagesHermano Oil Vs TRBDonna Faith ReyesNo ratings yet

- Euro-Med v. Province of BatangasDocument3 pagesEuro-Med v. Province of BatangasroyalwhoNo ratings yet

- Twin Peaks Mining vs. NavarroDocument5 pagesTwin Peaks Mining vs. NavarrocharmssatellNo ratings yet

- Resident Marine Mammals v. ReyesDocument2 pagesResident Marine Mammals v. ReyesAphr100% (1)

- Case Digest-Pollution-Adjudication-Board-Vs-CaDocument1 pageCase Digest-Pollution-Adjudication-Board-Vs-CaAngela Mitchelle TorresNo ratings yet

- Lim VS Laguio DigestDocument3 pagesLim VS Laguio DigestJude ChicanoNo ratings yet

- Disini v. Secretary of JusticeDocument3 pagesDisini v. Secretary of JusticeazuremangoNo ratings yet

- Recentjuris Remedial LawDocument81 pagesRecentjuris Remedial LawChai CabralNo ratings yet

- A. Heirs of Malabanan v. RepublicDocument67 pagesA. Heirs of Malabanan v. RepublicAnne Janelle GuanNo ratings yet

- 10 Republic Vs CA and Dela RosaDocument5 pages10 Republic Vs CA and Dela RosaJennylyn F. MagdadaroNo ratings yet

- West Tower v. PICDocument2 pagesWest Tower v. PICaustunNo ratings yet

- Freila Digest - Lladoc Vs CirDocument1 pageFreila Digest - Lladoc Vs CirRen MagallonNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 47065 June 26, 1940Document24 pagesG.R. No. 47065 June 26, 1940Nikk EncarnacionNo ratings yet

- Moday Vs CADocument2 pagesModay Vs CAJairus Adrian VilbarNo ratings yet

- Remedial Law Notes: Nelly Lim Vs Court of Appeals Case DigestDocument1 pageRemedial Law Notes: Nelly Lim Vs Court of Appeals Case DigestEman EsmerNo ratings yet

- Lepanto Vs WMCDocument4 pagesLepanto Vs WMCKaren Sheila B. Mangusan - DegayNo ratings yet

- Consti 2 Digest 132 Govt of Usa Vs Judge PurgananDocument13 pagesConsti 2 Digest 132 Govt of Usa Vs Judge PurgananRed HoodNo ratings yet

- Mindex Resources Development vs. Ephraim Morillo DigestDocument1 pageMindex Resources Development vs. Ephraim Morillo DigestlawNo ratings yet

- Sta Rosa Realty vs. AmanteDocument1 pageSta Rosa Realty vs. AmanteJerico GodoyNo ratings yet

- Hizon V CADocument1 pageHizon V CASarah CadioganNo ratings yet

- Re Anonymous Complaint Against Judge Edmundo AcunaDocument2 pagesRe Anonymous Complaint Against Judge Edmundo AcunaJMF1234No ratings yet

- Crescencio Vs PeopleDocument5 pagesCrescencio Vs PeopleKastin SantosNo ratings yet

- Acebedo Optical Vs CADocument2 pagesAcebedo Optical Vs CASherwin Delfin CincoNo ratings yet

- Benguet Vs LevisteDocument2 pagesBenguet Vs LevisteDelsie FalculanNo ratings yet

- Difference Relating To Immunity From Legal Process of A Special Rapporteur of The Commission of Human RightsDocument3 pagesDifference Relating To Immunity From Legal Process of A Special Rapporteur of The Commission of Human RightsAlljun Serenado0% (1)

- 166175-2011-Universal Robina Corp. v. Laguna LakeDocument6 pages166175-2011-Universal Robina Corp. v. Laguna LakedavidNo ratings yet

- Serrano Vs GallantDocument3 pagesSerrano Vs GallantAgnesNo ratings yet

- Rimando vs. Naguilian Emission Testing CenterDocument1 pageRimando vs. Naguilian Emission Testing CenterGeenea VidalNo ratings yet

- Universal Robina Corp Vs LLDADocument1 pageUniversal Robina Corp Vs LLDAMark Catabijan Carriedo100% (1)

- AVESTRUZ Atlas Consolidated Mining - Development Corporation v. Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesAVESTRUZ Atlas Consolidated Mining - Development Corporation v. Court of AppealsCarissa CruzNo ratings yet

- Director of Lands VS Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesDirector of Lands VS Court of AppealsJirah Lou-Anne SacliwanNo ratings yet

- Small Scale Mining ActDocument35 pagesSmall Scale Mining ActColyne Usodan100% (1)

- Masikip Vs City of PasigDocument2 pagesMasikip Vs City of PasigEm Asiddao-DeonaNo ratings yet

- Republic V CA and Dela RosaDocument3 pagesRepublic V CA and Dela RosaLavil KiuNo ratings yet

- Laguna Lake Development Authority VsDocument12 pagesLaguna Lake Development Authority VsJudeashNo ratings yet

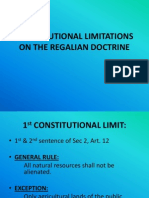

- Constitutional LimitationsDocument32 pagesConstitutional LimitationsXyleeApiladoNo ratings yet

- Villavicencio Vs LukbanDocument1 pageVillavicencio Vs LukbancharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Midway Maritime Vs CastroDocument3 pagesMidway Maritime Vs CastroMarie Gabay DamoclesNo ratings yet

- BOCEA vs. Teves Case DigestDocument2 pagesBOCEA vs. Teves Case DigestRhodz Coyoca Embalsado100% (1)

- Facts: On February 4, 1977, Then President Ferdinand E. Marcos Issued PresidentialDocument7 pagesFacts: On February 4, 1977, Then President Ferdinand E. Marcos Issued PresidentialAbigail DeeNo ratings yet

- Natres DigestDocument5 pagesNatres DigestSpidermanNo ratings yet

- Philippine Fisheries Code of 1998Document43 pagesPhilippine Fisheries Code of 1998Wally CalaganNo ratings yet

- Canon1 2 DigestedDocument16 pagesCanon1 2 DigestedBenedict John AureNo ratings yet

- Writ of Kalikasan and The Precautionary Principle and Disaster Risk Reduction and ManagementDocument5 pagesWrit of Kalikasan and The Precautionary Principle and Disaster Risk Reduction and ManagementDYbieNo ratings yet

- Case Digests Arts 282-284Document83 pagesCase Digests Arts 282-284Farrah MalaNo ratings yet

- Benguet Cosolidated Inc. vs. RepublicDocument3 pagesBenguet Cosolidated Inc. vs. RepublicjamimaiNo ratings yet

- 193 Benguet Consolidated, Inc. vs. RepublicDocument3 pages193 Benguet Consolidated, Inc. vs. RepublicRem SerranoNo ratings yet

- Benguet Vs RepublicDocument3 pagesBenguet Vs RepublicMirzi Olga Breech SilangNo ratings yet

- Nat Res Assigned CasesDocument17 pagesNat Res Assigned CasesTeoti Navarro ReyesNo ratings yet

- Ust 2013 Bar Essay Q Suggested Answers 1Document8 pagesUst 2013 Bar Essay Q Suggested Answers 1hbcgNo ratings yet

- Cases (Spec Pro)Document5 pagesCases (Spec Pro)Rose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines, Petitioner, vs. Hubert Jeffrey P. WEBB, RespondentDocument11 pagesPeople of The Philippines, Petitioner, vs. Hubert Jeffrey P. WEBB, RespondentRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines, Petitioner, vs. Hubert Jeffrey P. WEBB, RespondentDocument11 pagesPeople of The Philippines, Petitioner, vs. Hubert Jeffrey P. WEBB, RespondentRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- The Legal and Ethical Implications of Online Attorney-Client Relationships and Lawyer Advertising The PhilippinesDocument16 pagesThe Legal and Ethical Implications of Online Attorney-Client Relationships and Lawyer Advertising The PhilippinesMarlon CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Cases (Spec Pro)Document12 pagesCases (Spec Pro)Rose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Contract of Loan PDFDocument3 pagesContract of Loan PDFKatlen ValentinoNo ratings yet

- The Legal and Ethical Implications of Online Attorney-Client Relationships and Lawyer Advertising The PhilippinesDocument16 pagesThe Legal and Ethical Implications of Online Attorney-Client Relationships and Lawyer Advertising The PhilippinesMarlon CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Ra 9262Document20 pagesRa 9262Rose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- People Vs MatitoDocument13 pagesPeople Vs MatitoRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- SCC Chem Corp Vs CaDocument5 pagesSCC Chem Corp Vs CaRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Pamplona Vs MoretoDocument5 pagesPamplona Vs MoretoRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- From The Answers To Bar Examination QuesDocument37 pagesFrom The Answers To Bar Examination QuesRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Col AdDocument7 pagesCol AdRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Pleasantville Dev Vs CADocument10 pagesPleasantville Dev Vs CARose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Full Text & Digest #1Document49 pagesFull Text & Digest #1Rose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Subsidiary ImprisonmentDocument2 pagesSubsidiary ImprisonmentRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Banco Espanol Filipino V Peterson vBanco-Espanol-Filipino-v-Peterson Banco-Espanol-Filipino-v-Peterson Banco-Espanol-Filipino-v-Peterson Banco-Espanol-Filipino-v-PetersonDocument2 pagesBanco Espanol Filipino V Peterson vBanco-Espanol-Filipino-v-Peterson Banco-Espanol-Filipino-v-Peterson Banco-Espanol-Filipino-v-Peterson Banco-Espanol-Filipino-v-PetersonPaul Christian Balin CallejaNo ratings yet

- 1 Morata vs. GoDocument9 pages1 Morata vs. GoMo KeeNo ratings yet

- Legal Wriing CasesDocument43 pagesLegal Wriing CasesRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Mercado Vs EspinocillaDocument7 pagesMercado Vs EspinocillaRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Salvador Vs CADocument15 pagesSalvador Vs CARose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Delima Vs CADocument4 pagesDelima Vs CARose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- EnviLaw 1-Aug 13-20Document12 pagesEnviLaw 1-Aug 13-20Rose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Banco Espanol Vs CADocument4 pagesBanco Espanol Vs CARose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Estoque Vs PajimulaDocument3 pagesEstoque Vs PajimulaRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Go Ong v. CA 154 Scra 270Document5 pagesGo Ong v. CA 154 Scra 270Karla Marie TumulakNo ratings yet

- Estoque Vs PajimulaDocument3 pagesEstoque Vs PajimulaRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Melencio Vs LayDocument12 pagesMelencio Vs LayRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Go Ong Vs CADocument4 pagesGo Ong Vs CARose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Proposed Subpoena RequestDocument2 pagesProposed Subpoena RequestMatt MacariNo ratings yet

- Ruling in Lawsuit Filed by Businesses On Ocean Drive in Miami BeachDocument8 pagesRuling in Lawsuit Filed by Businesses On Ocean Drive in Miami BeachAndreaTorresNo ratings yet

- Julian Jaron v. Hy Frank, 227 F.2d 277, 1st Cir. (1955)Document5 pagesJulian Jaron v. Hy Frank, 227 F.2d 277, 1st Cir. (1955)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Nick Russo, James Lowery, Joseph Pine, V.L. Underhill, Jeff Underhill, Harry Almerico, Felipe Muratte, Renee Sanchez, 796 F.2d 1443, 11th Cir. (1986)Document26 pagesUnited States v. Nick Russo, James Lowery, Joseph Pine, V.L. Underhill, Jeff Underhill, Harry Almerico, Felipe Muratte, Renee Sanchez, 796 F.2d 1443, 11th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Et Al.: Court Use OnlyDocument2 pagesEt Al.: Court Use OnlyBrownBananaNo ratings yet

- LBP Vs MartinezDocument4 pagesLBP Vs MartinezSanjay FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Legal FormsDocument190 pagesPhilippine Legal Formsjalco companyNo ratings yet

- Jurado Civpro DigestDocument4 pagesJurado Civpro DigestShin KudoNo ratings yet

- United States v. Anthony Grado, Thomas Anzeulotto, AKA "Tommy Red,", 104 F.3d 351, 2d Cir. (1996)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Anthony Grado, Thomas Anzeulotto, AKA "Tommy Red,", 104 F.3d 351, 2d Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Spearman v. Robinson Steel Co - Document No. 3Document3 pagesSpearman v. Robinson Steel Co - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Santos vs. Pizardo, GR No. 151452Document1 pageSantos vs. Pizardo, GR No. 151452John Roel VillaruzNo ratings yet

- Ruling-Civil Application No. E583 of 2023Document22 pagesRuling-Civil Application No. E583 of 2023nicole gichuhiNo ratings yet

- Macasaet v. People, 452 SCRA 255Document11 pagesMacasaet v. People, 452 SCRA 255JNo ratings yet

- 15 Excellent Quality Apparel, Inc. .V Win Multiple Rich Builders, Inc., 578 SCRA 272 (2009)Document16 pages15 Excellent Quality Apparel, Inc. .V Win Multiple Rich Builders, Inc., 578 SCRA 272 (2009)Jan CarzaNo ratings yet

- Rule 13-Filing & Service of PleadingsDocument14 pagesRule 13-Filing & Service of PleadingsEller-JedManalacMendozaNo ratings yet

- Cavili vs. Florendo: - Third DivisionDocument9 pagesCavili vs. Florendo: - Third DivisionFatima MagsinoNo ratings yet

- CD Intengan v. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 128996 February 15 2002Document5 pagesCD Intengan v. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 128996 February 15 2002Dan ChuaNo ratings yet

- Jose v. Javellana, G.R. No. 158239, January 25, 2012Document3 pagesJose v. Javellana, G.R. No. 158239, January 25, 2012Kcompacion100% (1)

- Caterpillar Inc v. SamsonDocument10 pagesCaterpillar Inc v. SamsonErika Mariz CunananNo ratings yet

- Compiled Case Digests (Rules 17 To 21)Document49 pagesCompiled Case Digests (Rules 17 To 21)Jec Luceriaga BiraquitNo ratings yet

- Thomas Lynn Cramer v. Secretary, Dept. of Corr., 461 F.3d 1380, 11th Cir. (2006)Document5 pagesThomas Lynn Cramer v. Secretary, Dept. of Corr., 461 F.3d 1380, 11th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pasok V ZapatosDocument4 pagesPasok V ZapatosPatricia GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Bail Reform Check Sheet Courtesy of NJ CourtsDocument1 pageBail Reform Check Sheet Courtesy of NJ Courtsjmjr30No ratings yet

- GR No. 173082 (2014) - Rep. of The Phil. v. SandiganbayanDocument2 pagesGR No. 173082 (2014) - Rep. of The Phil. v. SandiganbayanNikki Estores GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Legal Writing, Quiz.2020-2021Document2 pagesLegal Writing, Quiz.2020-2021Keith Jasper MierNo ratings yet

- USA v. Hamid Hayat - DEFENDANT'S MOTION FOR RELIEF UNDER 28 U.S.C. 2255Document251 pagesUSA v. Hamid Hayat - DEFENDANT'S MOTION FOR RELIEF UNDER 28 U.S.C. 2255Jerry VashchookNo ratings yet

- G.R. Nos.195011-19Document11 pagesG.R. Nos.195011-19Abby EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- Rule 119 (Cases 1-11)Document136 pagesRule 119 (Cases 1-11)Marshan GualbertoNo ratings yet

- Why Judge James P Cullen Should Be Impeached July 9, 2008Document12 pagesWhy Judge James P Cullen Should Be Impeached July 9, 2008Stan J. CaterboneNo ratings yet

- Response To Motion To Vacate California JudgmentDocument138 pagesResponse To Motion To Vacate California JudgmentJeff NewtonNo ratings yet