Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Orientación Vocacional

Uploaded by

victoria_2013Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Orientación Vocacional

Uploaded by

victoria_2013Copyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Vocational Behavior, 1, 305-3 15 (197 1)

Occupational Interests:

Male-Female or High Level-Low Level Dichotomy?

ESTHER E. DIAMOND1 32

Science Research Associates, Inc.

Chicago, Illinois

The relation between occupational level and masculine and feminine

interests was investigated to determine whether sex differences in interests

would be minimized at the high end of the occupational continuum and

dichotomized at the low end. Subjects were scored on four experimental

scales derived from Kuder OIS scales-Male, Female, High Occupational

Level, and Low Occupational Level. Scores were subjected to several analyses, including comparisons of mean differences within and across groups,

and an errors of classification study. In general, results were consistent with

the proposed hypothesis. A strong, unpredicted relation, for the two male

groups, between high occupational level and female interests was hypothesized to be the result of a verbal factor common to both sets of interests.

Long before womens liberation activities began receiving wide, almost

daily coveragein the press, increasing numbers of women were entering occupational fields that traditionally, in our society, had been dominated by men.

Until recently, however, instruments to measureoccupational interest had few

or no scalesfor women other than those for traditional womens work-housewife, elementary school teacher, nurse, librarian, office worker, secretary,and

so on. Even today, with a number of professional scaleson the Strong Vocational Interest Blank (SVIB) for women, and still more on the Kuder Occupational Interest Survey (OIS), mens and womens occupational interests are

frequently considered to be quite different, even in the samefield, and use of

separatescalesor samescaleswith separatenorms prevails. Most investigators

of the assumeddifferences between mens and womens occupational interests

lReprints may be obtained from the author, Science Research Associates, 259 East

Erie St., Chicago, Illinois 60611.

Parts of this study were briefly summarized in the following: Diamond, E. E.

Occupational level versus sex group as a system of classification. Proceedingsof fhe 76th

Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, 1968, 3, 199-200 (Summary); Relationship between occupational level and masculine and feminine interests.

Proceedings of the 78th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association,

1970, 5, 177-178 (Summary).

305

Copyright @ 1971 by Academic Press, Inc.

306

ESTHER

E. DIAMOND

have explained these differences, to varying degrees,within the context of

overall psychosocial role, including sex role.

Roe (1956) held that, with reference to occupations, the psychological

and sociological differences between the sexesare much more important than

primary and secondary physical differences. Psychological and social differences, she maintained, form a continuum, and the actual physical fact of

maleness or femalenessis not necessarily an indication of location at the

masculine or feminine end of the scale. There are some women, according to

Roe, who are more masculine than some men, and vice versa. Differences in

relative masculinity-femininity are related in many ways to occupational interests [p. 581.

Super (1957) viewed occupations as organizations of social roles, with

vocational development being understood partly in terms of the way in which

the individual meets role expectations. As a child, a boy is called on to be

brave and strong, a girl to be kind and gentle. The roletaking is both conscious and unconscious; children and adults emulate role models sometimes

by design, sometimeswithout awarenessof the identification [pp. 46471.

Tyler (19.51) saw a girls role model as primarily a sex model, while she

perceived a boys role model as beginning as a sex model and developing into

a differentiated occupational model. Even in the first grade, Tyler observed,

most boys have begun to see themselves and their roles according to the

different kinds of positions they might occupy in adult life; most girls, on the

other hand, see themselvesas homemakers like their mothers, regardlessof

special abilities.

Strong (1943) found that the interests of men and women were, on the

whole, more similar than dissimilar, but that they could be made to appear

quite dissimilar when their interest blanks were scored on the MF (Masculinity-Femininity) scaleof the SVIB.

Darley and Hagenah(1955) found that noncareer-orientedwomen who

work for a short time before marriage at the traditional womens jobs described above tend to score higher on the feminine end of the SVIB Masculinity-Femininity (MF) scalethan do career-oriented women, and that womens

interests are generally less channelized or professionally intense than those of

men.

More than 30 years ago, Crissy and Daniel (1939), in a factor analysis of

the SVIB, found four factors in the womens scales. Three of these corresponded to three factors in the mens scales-interest in people, interest in

language, and interest in science. A fourth factor, which the investigators

identified as interest in male association, had no counterpart in the mens

scalesand appearedto represent nonprofessionalinterests mainly-including an

interest in detail and order. Seder (1940) studied the scoresof 100 women

physicians and 100 life insurance saleswomenon 35 scalesof the mens and

womens forms of the SVIB. A factor analysis failed to substantiate the com-

307

OCCUPATIONAL INTERESTS

mon claim that womens interests show different factors from those of men

and Sederconcluded that the factor loadingstended to support the hypothesis

that there is no femininity factor among the womens keys or masculinity factor among the mens keys. Strong (1943, pp. 574-576) disputed

Seders findings. He conceded that some mens and womens scalesmight be

used interchangeably, but argued that generally it is much better to score a

sex on its own scales. Much later, Laime and Zytowski (1964) investigated

the question of whether scores on the mens form could be predicted from

scores on the womens form. Among the highest correlations were those for

lawyers, which Strong (1943) and Seder (1940) had found among the lowest.

For seven scales,letter ratings were raised one letter in the change from the

womens form to the mens, an increase of five standard score units. On only

one scalewas the letter rating lowered.

Rand (1968) found that career-oriented college freshmenwomen scored

significantly higher than homemaking-oriented college freshmen women on

nine out of ten masculine characteristicsrelated to interest, potential, achievement, and competencies; but they also scored higher on a number of the

feminine variables! Rand concluded that the career-orientedwoman has redefined her role to include those behaviors appropriate to both sexes,while the

homemaking-oriented woman adheresclosely to her traditional feminine role.

TABLE 1

Occupational

CriterionGroups Used to Construct

the Four Experimental Scales

Sex

Occupational

level

High

Male

Minister

Personnel

manager

Physician

Psychiatrist

Statistnzian

LOW

Baker

Carpenter

Plumbing

contractor

Television

repairman

Truck driver

Female

Administrative

dietitian

High school science teacher

Lawyer

Medical social

worker

Psychiatric social worker

Beautician

Dental assistant

Department store

saleswoman

Florist

Office clerk

308

ESTHER E. DIAMOND

Stanfiel (1970) found that women college students who completed both the

mens and the womens forms of the SVIB obtained a significantly greater

number of A scores on the mens form. Farmer and Bohn (1970) administered

the womens form of the SVIB twice to professional women subjects. first

using a standard administration and then using an experimental set almed at

reducing home-career conflict. On the second administration, subjects scored

higher on the Career scales and lower on the Home scales.

The purpose of the study reported here was to explore the relation

between occupational level and interests identified as masculine or feminine.

The study was specifically designed to determine whether it is possible for an

interest measure to discriminate between subjects more accurately with respect

to occupational level than with respect to sex group, and whether the occupational level scales based on the combined responses of men and women to an

interest inventory could successfully differentiate between high- and low-level

occupational interests for both sexes. It was hypothesized that sex differences

in occupationally relevant interests would be minimized at the upper end of

the occupational continuum, although they might be clearly differentiated at

the low end, where women are not likely to be employed as truck drivers or

construction workers and male stenographers and typists are the exception

rather than the rule.

METHOD

The interest measure employed in this study was the Kuder Occupational Interest Survey (OIS), Form DD. The OIS rationale eliminates use of a

general reference group; the values of each possible response for a given scale

are derived directly from the proportion of the criterion group marking that

response. Scores are reported as lambda coefficients, expressing the relation

between subjects responses and the characteristic responses of the criterion

group (Kuder, 1966).

Criterion groups for which 01s scales had been developed were selected,

a priori, on the basis of four gross classifications: Male, Female, High Occupational Level, Low Occupational Level. Occupational level was defined in accordance with a combination of criteria-level of responsibility, degree of independence and decision-making, and amount and kind of education required, as

described by the Occupational Outlook Handbook and the Dictionay of Occupational Titles and to some extent by the two-way classification of occupations (field by level) developed by Roe (1956). From the groups in each of

these classifications, five were chosen at random, making a total of 20 groups.

These are shown in Table 1. Four experimental scales-Male, Female, High

Occupational Level, and Low Occupational Level-were developed from the

combined response proportions for the groups in each of the four experimen-

309

OCCUPATIONAL INTERESTS

TABLE 2

Means and Standard Deviations for the Four Experimental Groups

on the Four Scales

Scale

High OL

male

Low OL

male

High OL

female

Low OL

female

Female

Male

Group

High occupational level

Low occupatlonal level

SD

SD

SD

SD

s22

.079

,457

,080

.535

.075

.440

.090

.443

.116

,339

,121

,314

,112

,476

,132

.45 1

.085

S42

,105

.545

.lOO

,446

.098

,395

.080

.554

.080

.435

.090

522

,077

tal classifications, using the systememployed in developing the 01s scales

(Ruder, 1966). Three-hundred cross-validationsubjects,75 for each of the four

experimental classifications, were randomly selected from an available pool of

OIS cross-validation subjects. Each subject was scored on each of the four

experimental scales.

Mean differences between scoreson the four scaleswere compared both

within groups and across groups. Next, an errors of classification study was

conducted to determine the frequency with which subjects were classified

correctly on the basis of sex and of level. Correct classification was defined as

scoring higher on the scale representing subjects actual sex or occupational

level than on the scale for the opposite sex or occupational level. Ties were.

counted as correct classifications.

RESULTS

Mean Differences

Means and standard deviations of subjects on the four experimental

scales are given in Table 2. As expected, means for both High Occupational

Level Males and High Occupational Level Femaleswere highest on the High

Occupational Level scale. For Low Occupational Level Males, mean score on

the Low Occupational Level scale was highest, while for Low Occupational

Level Females,mean score on the Female scalewas highest. For the two High

Occupational Level groups, mean score on the Low Occupational Level scale

310

ESTHER E. DIAMOND

was lowest; for Low Occupational Level Males, mean score on the High Occupational Level scale was lowest; and for Low Occupational Level Females,

mean score on the Male scalewas lowest.

For all groups, differencesbetween mean scoreson the Male and Female

scales and between mean scores on the High and Low Occupational Level

scales were significant (p < .Ol). For both High Occupational Level groups,

differences between mean scores on the scale for their own sex and on the

High Occupational Level scale were not significant. For both groups of Low

Occupational Level subjects, differences between mean scoreson the scale for

their own sex and on both the High and Low Occupational Level scaleswere

significant (JJ< .Ol). High Occupational Level groups of both sexesalso scored

TABLE 3

Relevant Mean Differences between Scores

High occupational level males (N = 75)

SE

t ratio

M-Fa

M-high OL

M-low OL

,065

,088

6.37*

-.014

.071

-1.67

.082

.057

12.49*

High-low

OL

.096

.09.5

8.72*

Low occupational level males (N = 75)

M

SE

t ratio

M-F

M-High OL

.104

.083

10.874*

.I29

.07?

14.482*

M-Low OL

-.033

.052

-5.430*

Low-high

OL

.I62

.102

13.654*

High occupational level females (N = 75)

F-M

M

SE

t ratio

SE

t ratio

F-High OL

F-Low OL

,091

-.003

.096

.089

.07 1

.062

-.374

13.392*

8.847*

Low occupational level females (N = 75)

F-M

F-High OL

F-Low OL

.I59

,119

.058

17.814*

.032

.06 1

4.514*

.077

17.937*

M represents male; F represents female.

*p < .Ol.

High-low

OL

.099

.102

8.451*

Low-hgh

OL

.087

.091

8.263*

311

OCCUPATIONAL INTERESTS

TABLE 4

Relevant Mean Differences Between Scores

Compared Across Groups

Group I

(N = 75)

High OL male

High OL female

High OL male

High OL female

High OL male

High OL male

Low OL male

Low OL male

High OL male

High OL female

High OL male

High OL female

High OL male

Low OL male

Group II

(N = 75)

Low OL male

Low OL female

Low OL male

Low OL female

High OL female

High OL female

Low OL female

Low OL female

Low OL male

Low OL female

Low OL male

Low OL female

High OL female

Low OL female

Scale on

which

compared

Mean

difference

Male

Female

Female

Male

Male

Female

Male

Female

High OL

High OL

Low OL

Low OL

High OL

Low OL

.079

.012

,118

.096

.07 1

.085

.048

.215

.221

.llO

.036

.076

.OlO

.046

4.65**

.86

6.94**

6.86**

5.07**

6.07**

2.82**

12.65**

13.00**

7.86**

2.12s

5.43**

.71

2.71**

*p < .05.

**p < .Ol.

significantly higher on the scale for the other sex than did the Low Occupational Level groups. The f-test results are shown in Table 3.

Results of a second series of t tests, conducted to determine the significance of the differences between mean scoresacrossgroups, are given in Table

4.

For the differences between the means of High and Low Occupational

Level Males and between the means of High and Low Occupational Level

Females on the High Occupational Level scale, p < .Ol. For differences between means on the Low Occupational Level scale,p < .05 for High and Low

Occupational Level Males and p < .Ol for High and Low Occupational Level

Females. For the differences between means of High and Low Occupational

Level Males on the Male scale, p < .Ol, but the comparable difference for

females,between means of High and Low Occupational Level Femaleson the

Female scale,was not significant.

High Occupational Level groups of both sexesscored higher on the scale

for the other sex than did the Low Occupational Level groups; for differences

between these means, between the meansof the two High Occupational Level

groups, and between the meansof the two Low Occupational Level groups on

both the Male and Female scales,p < .Ol. The difference between the means

of the two High Occupational Level groups on the High Occupational Level

scale was not significant, but p < .Ol for the difference between the meansof

the two Low Occupational Level groups on the Low Occupational Level scale.

312

ESTHER E.DIAMOND

Since it was noted that the differences between means on the Male and

Female scales were considerably smaller for the two High Occupational Level

groups than for the two Low Occupational Level groups, a third series of t

tests was conducted to determine the significance of the difference between

scores on the Male and Female scales across occupational levels and sex

groups. Only the difference between the mean scores on the Male and Female

scales for the two High Occupational Level groups was not significant; for all

other differences, p < .O1.

Errors of Classification

High Occupational Level subjects were more frequently classified correctTABLES

Intercorrelations of the Scoreson the Four Experimental Scales

Scale

Group

(N=75)

in each)

Male

Total group

High OL male

Low OL male

High OL female

Low OL female

Female

Total group

High OL male

Low OL male

High OL female

Low OL female

High OL

Total group

High OL male

Low OL male

High OL female

Low OL female

Low OL

Total group

High OL male

Low OL male

High OL female

Low OL female

Male

Female

High OL

Low OL

.32

.40

.76

.58

.55

.62

.58

.77

.80

.77

.56

.78

.92

.66

.70

.76

.76

.92

.I6

.78

.58

.62

.80

.82

.70

.24

.35

.66

.48

.42

OCCUPATIONAL

INTERESTS

313

ly on the basis of scores on the High Occupational Level scale than on the

basis of scores on the Male and Female scales(p > .05), and Low Occupational Level Subjects were more frequently classified correctly on the basis of

scores on the Male and Female scalesthan on the basis of scoreson the Low

Occupational Level scale(p < .Ol).

Intercorrelations

Intercorrelations of the scales, shown in Table 5, ranged from .24 for

High Occupational Level with Low Occupational Level, to .76 for Female

with High Occupational Level, for the total group. Correlations are also given

for each of the four groups.

DISCUSSION

In general, the differences between mean scores were in the direction

suggestedby the hypothesis, with High Occupational Level subjects scoring

highest on the High Occupational Level scale and Low Occupational Level

subjects on either the scale for the appropriate sex group (Low Occupational

Level Females) or the Low Occupational Level scale(Low Occupational Level

Males). For all four groups, differences between mean scoreson the High and

Low Occupational Level scalesand on the Male and Female scaleswere significant, indicating the power of the scales to differentiate accurately between

both occupational levels and both sexes. Also consistent with the proposed

hypothesis, sex differences with regard to interests appeared to be minimized

at the high end of the occupational continuum but sharply differentiated at

the lower end.

The findings also indicate a high degreeof relationship between the High

Occupational Level scale and the Female scale. A possible explanation is that

the interests of High Occupational Level subjects are highly verbal, and the

verbal factor is generally associatedwith the feminine end of the MF continuum. Strong (1966, p. 19) found that educated men in particular score toward

the feminine end of the MF scale, which was interpreted to mean that they

like books and art, clean inside work, and activities that are typically feminine in society as a whole.

It seemsapparent, however, that while for male subjectsthere is a high

degree of relationship between high occupational level and interests, possibly

verbal, identified with the feminine end of the MF continuum, the sameis not

true for female subjects. For High Occupational Level Females, the strong

association between the Male and High Occupational Level scalesmight reflect

the fact that, for women, interest in attaining a high occupational level is

consonant with living in a mans world, competing with males, and consequently having interests highly similar to theirs.

314

ESTHER E. DIAMOND

For LOW Occupational Level Females, on the other hand, the correlations of the sex group scales with the occupational level scaleshad a much

smaller range, and for each of the two occupational levels the degree of

relationship with male and female scaleswas equivalent. These findings may

reflect an ambivalence in the lives of women holding low occupational level

occupations. It is possible, as has been pointed out by Strong (1943, 1959)

and Harmon (1967) that the circumstancesof womens lives may force them

into occupations which they would not choose if they were free to select on

the basis of vocational interests alone-that many women select their jobs on

the basis of convenience rather than genuine interest in the work. Low occupational level jobs are often more convenient for the married woman, particularly if she has children, from the point of view of regular hours, low pressure,

and nearnessto home. Yet many of these women may be more highly educated than their jobs would indicate. Males, on the other hand, are much

more likely to go into occupations consistent with their education and ability.

This explanation may in part also account for the fact that more Low Occupational Level Females than Low Occupational Level Males were classified as

High Occupational Level subjects.

The picture, perhaps, is changing-though far more slowly than one

might expect. In 1950, 10% of all women workers were in technical and

professional jobs, compared with 15% today. According to the U.S. Department of Labor (Waldman, 1970), approximately 70% of all women with 5 or

more years of college, and more than half of all women with 4 years of

college, are in the labor force. The more education a woman has, the more

likely she is to work. This high labor force participation rate indicates a very

strong commitment to both marriage and a career, a far stronger one than

prevailed among high school graduates the same ages (57%) [p. 161. But

even with this increase in percentage in professional jobs, the same report

points out: The broad category of professional jobs is a notorious example

of a field divided along sexual lines. Here, about two-thirds of all women are

employed as either nurses or teachers, and even as teachers, most women

teach in the primary gradeswhile most men teach in high school [p. 121.

REFERENCES

Crissy, W. J. E., & Daniel, W. J. Vocational interest factors in women. Journal of Applied

Psychology,

1939, 23, 448-494.

Darley, J. G., & Hagenah, T. Vocational interest measurement. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 1955.

Farmer, H. S., & Bohn, M. J., Jr. Home-career conflict reduction and the level of career

interest in women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 1970, 17, 228-232.

Harmon, L. W. Womens interests-fact or fiction? Personnel and Guidance Journal, 1967,

45. 895-900.

OCCUPATIONAL INTERESTS

315

Kuder, G. F. General manual, Occupational Interest Survey, Form DD. Chicago: Science

Research Associates, 1966.

Laime, B. F., & Zytowski, D. G. Womens scores on the M and F forms of the SVIB.

Vocational Guidance Quarterly, 1964, 12, 116-118.

Rand, L. Masculinity orc:feminity ? Differentiating career-oriented and homemakingoriented college freshmen women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 1968, 15,

444-450.

Roe, A. The psychology of occupations. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1956.

Seder, M. A. The vocational interests of professional women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 1940, 24, 130-143, 265-212.

Stantiel, J. D. Administration of the SVIB Mens form to women counselees. Vocational

Guidance Quarterly, 1970, 19, 22-21.

Strong, E. K., Jr. Vocational interests of men and women. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford

University Press, 1943.

Strong, E. K., Jr. Manual for Strong Vocational Interest Blank. (Rev. by D. Campbell)

Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1966.

Super, D. E. Vocational development: A framework for research. Horace Mann-Lincoln

Institute of School Experimentation, Career Pattern Study No. 1. New York:

Teachers College, Columbia University, 1957.

Tyler, L. The relationship of interests to abilities and reputation among first-grade

children. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 1951, 11, 255-264.

Waldman, E. Women at work: Changes in the labor force activity of women. Reprint

2677, MonthZy Labor Review, June 1970, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United

States Department of Labor.

Received: November 30, 1970

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Dear Future Child of Mine Psychology 1100 Class Assignment ch15Document2 pagesDear Future Child of Mine Psychology 1100 Class Assignment ch15api-251996923No ratings yet

- Sex Differences in Coping Behavior - A Meta Analytic Review and An Examination of Relative CopingDocument30 pagesSex Differences in Coping Behavior - A Meta Analytic Review and An Examination of Relative CopingSilvio Garcia ParedesNo ratings yet

- Gender ResearchDocument8 pagesGender ResearchDiddlyNo ratings yet

- Thompson (2000) Four-Frame Model PDFDocument24 pagesThompson (2000) Four-Frame Model PDFHenRy GoeyNo ratings yet

- UNIT: EDU20003 Contemporary Perspectives of Learning and Development Assessment 2Document12 pagesUNIT: EDU20003 Contemporary Perspectives of Learning and Development Assessment 2thunguyenhoang0303100% (1)

- Critical Reading On The Calling's 'Stigmatized'Document15 pagesCritical Reading On The Calling's 'Stigmatized'colenearcainaNo ratings yet

- Aspie-Quiz: Your Aspie Score: 157 of 200 Your Neurotypical (Non-Autistic) Score: 58 of 200 You Are Very Likely An AspieDocument14 pagesAspie-Quiz: Your Aspie Score: 157 of 200 Your Neurotypical (Non-Autistic) Score: 58 of 200 You Are Very Likely An AspieblakennetNo ratings yet

- Same Old Hocus PocusDocument15 pagesSame Old Hocus PocusFemi OlowoNo ratings yet

- Gender Displacement in Contemporary Horror (Shannon Roulet) 20..Document13 pagesGender Displacement in Contemporary Horror (Shannon Roulet) 20..Motor BrethNo ratings yet

- Knudson Martin Et Al-2015-Journal of Marital and Family TherapyDocument16 pagesKnudson Martin Et Al-2015-Journal of Marital and Family TherapyDann Js100% (1)

- Beyond The Gender Stereotype New Age Advertising in IndiaDocument4 pagesBeyond The Gender Stereotype New Age Advertising in IndiaResearch ParkNo ratings yet

- Gender Representation in English TextbooksDocument9 pagesGender Representation in English TextbooksDr Irfan Ahmed RindNo ratings yet

- Ramos, A. Lattore, Tomas & Ramos, J. (2022)Document11 pagesRamos, A. Lattore, Tomas & Ramos, J. (2022)Maria AnaNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare and The Nature of Women PDFDocument46 pagesShakespeare and The Nature of Women PDFMariana CastilloNo ratings yet

- Final Exam NotesDocument21 pagesFinal Exam Notesmmarks8No ratings yet

- Eli Rezkallah S "In A Parallel Universe" Photography: Attempting Reversal Gender Stereotype in Mad-Men Era AdvertisingDocument18 pagesEli Rezkallah S "In A Parallel Universe" Photography: Attempting Reversal Gender Stereotype in Mad-Men Era AdvertisingAnisa Debby NiculNo ratings yet

- Feminism (Gender Sterotypes)Document31 pagesFeminism (Gender Sterotypes)Pavan RajNo ratings yet

- Gender & SocietyDocument17 pagesGender & SocietyMushmallow Blue100% (1)

- Socialization To Gender Roles Popularity Among Elementary School Boys and GirlsDocument20 pagesSocialization To Gender Roles Popularity Among Elementary School Boys and GirlsPatricia JoisNo ratings yet

- Semester 1 Sociology Abhijeet AudichyaDocument20 pagesSemester 1 Sociology Abhijeet AudichyaABHIJEET AUDICHYANo ratings yet

- Grade 8 ExamDocument7 pagesGrade 8 ExamAnalyn QueroNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Gender-Analysis FrameworksDocument146 pagesA Guide To Gender-Analysis FrameworksOxfamNo ratings yet

- Scott - Millennial FantasiesDocument15 pagesScott - Millennial FantasiesJuliana Sandoval Alvarez100% (1)

- Message Source-Characteristics of The Person Who Delivers The MessageDocument13 pagesMessage Source-Characteristics of The Person Who Delivers The MessageShyam Kumar BanikNo ratings yet

- Gender and DisabilityDocument14 pagesGender and DisabilityefunctionNo ratings yet

- Gender Bias and Gender Steriotype in CurriculumDocument27 pagesGender Bias and Gender Steriotype in CurriculumDr. Nisanth.P.M100% (2)

- Media and Gender Stereotyping, The Need For Media LiteracyDocument7 pagesMedia and Gender Stereotyping, The Need For Media LiteracyMaëlenn DrévalNo ratings yet

- Hegemonic Masculinity in Boys ArticleDocument8 pagesHegemonic Masculinity in Boys ArticleSebastian CoraisacaNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Parental Influence On Their Children Career Choice PDFDocument64 pagesThe Effects of Parental Influence On Their Children Career Choice PDFKatie BarnesNo ratings yet

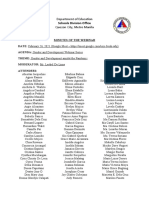

- Minutes - Gender and Development Webinar 02-26-2021Document4 pagesMinutes - Gender and Development Webinar 02-26-2021Tet BCNo ratings yet