Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gastrotomia

Uploaded by

Jessica TovarCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gastrotomia

Uploaded by

Jessica TovarCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 20

Loughin CA, Marino DJ: Delayed primary surgical treatment in a

dog with a persistent right aortic arch, J Am Anim Hosp Assoc

44:258, 2008.

MacPhail CM, Monnet E, Twedt DC: Thoracoscopic correction of

persistent right aortic arch in a dog, J Am Anim Hosp Assoc

37:577, 2001.

Monnet E: Thoracoscopic correction of persistent right aortic arch.

In Tams TR, Rawlings CA, editors: Small animal endoscopy, ed 3,

St. Louis, 2011, Elsevier, Mosby, p. 501.

Surgery of the Stomach

GENERAL PRINCIPLES AND TECHNIQUES

DEFINITIONS

Gastrotomy is an incision through the stomach wall into the

lumen. Partial gastrectomy is a resection of a portion of the

stomach, and gastrostomy is the creation of an artificial

opening into the gastric lumen. Gastropexy permanently

adheres the stomach to the body wall. Removal of the pylorus

(pylorectomy) and attachment of the stomach to the duodenum (gastroduodenostomy) is a Billroth I procedure.

Attachment of the jejunum to the stomach (gastrojejunostomy) after a partial gastrectomy (including pylorectomy) is

a Billroth II procedure. In a pyloromyotomy, an incision is

made through the serosa and muscularis layers of the pylorus

only. For a pyloroplasty, a full-thickness incision and tissue

reorientation are performed to increase the diameter of the

gastric outflow tract.

PREOPERATIVE CONCERNS

Gastric surgery is commonly performed to remove foreign

bodies (see p. 479) and to correct gastric dilatation-volvulus

(see p. 482). Gastric ulceration or erosion (see p. 490), neoplasia (see p. 494), and benign gastric outflow obstruction

(see p. 488) are less common indications. Gastric disease may

cause vomiting (intermittent or profuse and continuous) or

just anorexia. Dehydration and hypokalemia are common in

vomiting animals and should be corrected before induction

of anesthesia. Alkalosis may occur secondary to gastric

fluid loss; however, metabolic acidosis may also be seen.

Hematemesis may indicate gastric erosion or ulceration or

coagulation abnormalities. Peritonitis arising from perforation of the stomach caused by necrosis or ulceration often is

lethal if not treated promptly and aggressively (see p. 373).

Aspiration pneumonia or esophagitis may also occur in

vomiting animals. If possible, severe aspiration pneumonia

(see p. 425) should be treated before induction of anesthesia

for gastric surgery.

Mild esophagitis generally can be treated by withholding

food for 24 to 48 hours (see p. 425) and treating with

Surgery of the Digestive System

461

H2-receptor antagonists. However, severe esophagitis may

necessitate withholding oral food for 7 to 10 days. A gastrostomy tube (see p. 106) placed during surgery may be considered if continued vomiting is not expected. If continued

vomiting is likely, an enteral feeding tube is preferred (see p.

107). Treatment with H2-receptor antagonists (i.e., cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine; see Box 20-13) or proton pump

inhibitors (i.e., omeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole; see

Box 20-13) is important. Orally administered sucralfate slurries may help, but they should be given 1 hour after other

medications (see p. 425). Administration of metoclopramide

or cisapride will improve gastric emptying. Antibiotics effective against oral contaminants (e.g., ampicillin, amoxicillin,

clindamycin, cephalosporins) may be considered (see Box

20-14 on p. 425).

When possible, food should be withheld for at least 8 to

12 hours before surgery to ensure that the stomach is empty.

If gastroscopy will be performed, it is best to fast the patient

for at least 18 and preferably 24 hours before the procedure.

However, fasting for only 4 to 6 hours may help prevent

hypoglycemia in pediatric patients (see the discussion on

anesthetic and surgical management of pediatric patients,

which follows). Surgery for gastric obstruction, distention,

malpositioning, or ulceration should be performed as soon

as possible after the animals condition has been stabilized.

ANESTHETIC CONSIDERATIONS

Numerous anesthetic protocols have been used in stable

animals undergoing abdominal surgery (see Table 19-1 on

p. 358). See Table 20-4 for anesthetic recommendations for

the acute abdomen.

ANTIBIOTICS

Perioperative antibiotics may be used if the gastric lumen

will be entered; however, animals with normal immune

function undergoing simple gastrotomy (i.e., proper aseptic

technique and no spillage of gastric contents) rarely require

them. If antibiotics are used (e.g., cefazolin; 22mg/kg given

intravenously at induction; repeat once or twice at 2 to 4

hour intervals), they should be given intravenously before

induction of anesthesia and continued for up to 12 hours

postoperatively. Except for Helicobacter organisms, bacteria

are scarce in the stomach compared with other parts of the

gastrointestinal tract because of the low gastric pH.

SURGICAL ANATOMY

The stomach can be divided into the cardia, fundus, body,

pyloric antrum, pyloric canal, and pyloric ostium. The

esophagus enters the stomach at the cardiac ostium. The

fundus is dorsal to the cardiac ostium, and although relatively small in carnivores, it is easy to identify on radiographs

because it typically is filled with gas. The body of the stomach

(the middle one-third) lies against the left lobes of the liver.

The pyloric antrum is funnel-shaped and opens into the

pyloric canal. The pyloric ostium is the end of the pyloric

canal that empties into the duodenum.

Suggested reading

Holt D, Heldmann E, Michel K, et al: Esophageal obstruction

caused by a left aortic arch and an anomalous right patent ductus

arteriosus in two German shepherd littermates, Vet Surg 29:264270, 2000.

Clinical signs were alleviated in these two dogs by dissection and

division of the patent right ductus arteriosus.

Isakow K, Fowler D, Walsh P: Video-assisted thoracoscopic division

of the ligamentum arteriosum in two dogs with persistent right

aortic arch, J Am Vet Med Assoc 217:1333, 2000.

The technique is described in detail. The laparoscopic procedure

took longer than an thoracotomy, but the authors suggested that the

decreased complications made it a desirable technique.

Lee KC, Lee HC, Jeong SM, et al: Radiographic diagnosis of esophageal obstruction by persistent right aortic arch in a kitten, J Vet

Clin 20:248, 2003.

This case report describes a 3-month-old, male Persian kitten with

PRAA.

Vianna ML, Krahwinkel DJ: Double aortic arch in a dog, J Am Vet

Med Assoc 225(8):1222, 2004.

This is a case report of a dog that did well after surgery; however,

most dogs die or are euthanatized.

White RN, Burton CA, Hale JSH: Vascular ring anomaly with coarctation of the aorta in a cat, J Small Animl Pract 44:330, 2003.

This 1-month-old, male domestic short-hair cat had PRAA with a

coexisting aberrant left subclavian artery, which was the primary

cause of esophageal constriction. Following surgery the cat was

clinically normal.

Chapter 20

Surgery of the Digestive System 461.e1

TABLE 20-4

Anesthetic Considerations for the Patient with an Acute Abdomen

Preoperative Considerations

Associated conditions Dehydration

Electrolyte abnormalities

Hypotension

Anemia

Arrhythmias

Blood work

HCT

Electrolytes

BUN

Cr

TP

Lactate

Urinalysis

Blood gas if available

Physical exam

Often a younger patient that was previously healthy

May be dehydrated, tachycardic or bradycardic, hypotensive, retching, vomiting, or hypothermic

Painful or distended abdomen may be present

Other diagnostics

Blood pressure

ECG

X-ray (abdominal)

Premedications

Rehydrate over 4-6 hours if possible; if emergent, may have to give more rapid boluses to

expedite time to surgery.

Correct electrolyte and metabolic abnormalities if time permits

Avoid sedatives in depressed or cardiovascularly compromised patients.

Avoid alpha 2 agonists and acepromazine.

If patient is stable and anxious, give:

Midazolam (0.2mg/kg IV, IM) or

Diazepam (0.2mg/kg IV)

If patient is not depressed, then give:

Hydromorphone* (0.1-0.2mg/kg IV, IM in dogs; 0.05-0.1mg/kg IV, IM in cats), or

Morphine (0.1-0.2mg/kg IV or 0.2-0.4mg/kg IM), or

Buprenorphine (0.005-0.02mg/kg IV, IM)

Intraoperative Considerations

Induction

Maintenance

Fluid needs

Monitoring

Blocks

If dehydrated or unstable, give the following:

Etomidate (0.5-1.5mg/kg IV), or

Ketamine (5.5mg/kg IV) and diazepam (0.28mg/kg IV)

If hydrated and stable, give the following:

Propofol (2-6mg/kg IV)

Isoflurane or sevoflurane, plus

Fentanyl (2-10g/kg IV PRN in dogs; 1-4g/kg IV PRN in cats) for short-term pain relief, plus

Fentanyl CRI (1-5g/kg IV loading dose, then 2-30g/kg/hr IV), or

Hydromorphone* (0.1-0.2mg/kg IV PRN in dogs; 0.05-0.1mg/kg IV PRN in cats), or

Buprenorphine (0.005-0.02mg/kg IV PRN), plus

Ketamine (low dose) (0.5-1mg/kg IV)

For hypotension (to keep MAP 60-80mmHg) give phenylephrine, ephedrine, norepinephrine,

or dopamine as needed

Two large IV cephalic or jugular catheters

10-20ml/kg/hr if open abdomen with higher evaporative losses, plus 3x EBL; higher rates of

fluids are necessary if dehydration not corrected preoperatively and animal is hypotensive

Consider colloids if persistent hypotension

Blood pressure

ECG

Respiratory rate

SpO2

EtCO2

Temperature

U/O

Epidural:

Morphine (0.1mg/kg preservative free) or

Buprenorphine (0.003-0.005mg/kg diluted in saline)

Avoid local anesthetics for spinal or epidural

Incisional:

Lidocaine (<5mg/kg in dogs; 2-4mg/kg in cats), or

Bupivicaine (<2mg/kg)

Chapter 20

Surgery of the Digestive System

463

TABLE 20-4

Anesthetic Considerations for the Patient with an Acute Abdomencontd

Postoperative Considerations

Analgesia

Fentanyl CRI (1-10g/kg IV loading dose, then 2-20g/kg/hr IV), or

Morphine (0.1-1mg/kg IV or 0.1-2mg/kg IM q1-4hr in dogs; 0.05-0.2mg/kg IV or

0.1-0.5mg/kg IM q1-4hr in cats) if no hypotension, or

Hydromorphone* (0.1-0.2mg/kg IV, IM q3-4hr in dogs; 0.05-0.1mg/kg IV, IM q3-4hr in

cats), or

Hydromorphone CRI (0.025-0.1mg/kg/hr IV in dogs), or

Buprenorphine (0.005-0.02mg/kg IV, IM q4-8hr or 0.01-0.02mg/kg OTM q6-12hr in cats),

plus

Monitoring

Blood work

Estimated pain score

+/ Ketamine CRI (2g/kg/min IV. If no previous loading dose, give 0.5mg/kg IV prior to CRI)

Avoid NSAIDs in patients with hypotension

SpO2

Blood pressure

HR

Respiratory rate

Temperature

U/O

ECG

HCT if significant blood loss

Repeat abnormal preoperative blood work

Serial blood glucose checks if necessary

Blood gas if available

Moderate to moderately severe

HCT, Hematocrit; TP, total protein; CR, creatinine; HR, heart rate; EBL, estimated blood loss; MAP, mean arterial pressure, U/O, urine output;

SpO2, oxygen saturation via a pulse oximeter; EtCO2, end tidal CO2; PRN, as needed; OTM, oral transmucosal.

*Monitor for hyperthermia in cats.

Buprenorphine is a better analgesic than morphine in cats.

NOTE The gastric mucosa accounts for half of

the stomachs weight. You can easily separate the

mucosa from the submucosa and serosa when raising

flaps or making partial thickness incisions during a

gastropexy or pyloromyotomy.

The gastric (lesser curvature) and gastroepiploic (greater

curvature) arteries supply the stomach and are derived from

the celiac artery. The short gastric arteries arise from the

splenic artery and supply the greater curvature. The portion

of the lesser omentum that passes from the stomach to

the liver is the hepatogastric ligament. The stomach of the

Beagle holds more than 500ml of fluid when distended (a

mature cats stomach may hold 300 to 350ml). When the

stomach is highly distended, it can be palpated beyond the

costal arch.

NOTE The short gastric vessels often are avulsed

in animals with gastric dilatation-volvulus, which typically accounts for the intra-abdominal hemorrhage

seen in these cases (see also the discussion of gastric

dilatation-volvulus on p. 482).

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Gastric surgery often is performed in small animals. Generally, performing a gastrotomy is safer than performing an

esophagotomy or enterotomy. Peritonitis is uncommon after

gastrotomy if proper techniques are used. Stricture or

obstruction is also rare. Billroth procedures are more difficult and may be associated with severe complications.

Gastroscopy

Endoscopic removal of foreign bodies is preferred over surgical removal but requires appropriate endoscopic snares.

Likewise, endoscopy is more sensitive than gastrotomy when

looking for erosions, ulcers, Physaloptera, and other small

lesions. However, it is imperative that the entire gastric

mucosa be systematically examined, including the fundus

and lower esophageal mucosa. Similarly, endoscopy is the

preferred method for gastric mucosal biopsy because it

allows one to obtain more tissue samples than surgery, which

is important because gastric mucosal lesions can be very

spotty. Scirrhous carcinomas, pythiosis, and submucosal

lesions are the most important gastric lesions that cannot be

reliably diagnosed with endoscopic biopsy. Rarely, intraoperative gastroscopy can be performed to help the surgeon

find a mucosal lesion (e.g., ulcer) that is not obvious

464

PART TWO

Soft Tissue Surgery

Gastrotomy

The most common indication for gastrotomy in dogs and

cats is removal of a foreign body (see p. 479). Make a ventral

incorporates the serosal and muscularis layers (Fig. 20-67,

D). As an alternative, close the mucosa in a simple continuous suture pattern as a separate layer to reduce postoperative bleeding. Before closing the abdominal incision, substitute

sterile instruments and gloves for those contaminated by

gastric contents. Whenever you remove a gastric foreign

body, be sure to check the entire intestinal tract for additional

material that could cause an intestinal obstruction.

midline abdominal incision from the xiphoid to the pubis.

Use Balfour retractors to retract the abdominal wall and

provide adequate exposure of the gastrointestinal tract.

Inspect the entire abdominal contents before incising the

stomach. To reduce contamination, isolate the stomach from

remaining abdominal contents with moistened laparotomy

sponges. Place stay sutures to assist in manipulation of the

stomach and help prevent spillage of gastric contents. Make

the gastric incision in a hypovascular area of the ventral

aspect of the stomach, between the greater and lesser curvatures (Fig. 20-66). Make sure the incision is not near the

pylorus, or closure of the incision may cause excessive tissue

to be enfolded into the gastric lumen, resulting in outflow

obstruction. Make a stab incision into the gastric lumen with

a scalpel (Fig. 20-67, A) and enlarge the incision with Metzenbaum scissors (Fig. 20-67, B). Use suction to aspirate

gastric contents and reduce spillage. Close the stomach with

2-0 or 3-0 absorbable suture material (e.g., polydioxanone,

polyglyconate) in a two-layer inverting seromuscular pattern

(Fig. 20-67, C). Include serosa, muscularis, and submucosa

in the first layer, using a Cushing or simple continuous

pattern, then follow it with a Lembert or Cushing pattern that

FIG 20-66. Preferred location of gastrotomy incisions.

from the serosal surface. Endoscopic polypectomy using

electrocautery has been described in one dog and one cat

and was associated with resolution of clinical signs for 12

and 21 months (Foy and Bach, 2010).

FIG 20-67. Gastrotomy. A, Make a stab incision into the gastric lumen with a scalpel.

B, Enlarge the incision with Metzenbaum scissors. C and D, Close the stomach with a

two-layer inverting seromuscular suture pattern.

Chapter 20

Surgery of the Digestive System

465

Partial Gastrectomy and Invagination

of Gastric Tissue

Partial gastrectomy is indicated when necrosis, ulceration, or

neoplasia involves the greater curvature, or middle portion,

of the stomach. Necrosis of the greater curvature is primarily

associated with gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV) and may

be treated by resection or invagination. Invagination does

not require opening of the gastric lumen (Fig. 20-68);

however, obstruction from excessive intraluminal tissue and

excessive bleeding is possible (Parton etal, 2006). Assess the

extent of necrosis by observing the serosal color, gastric wall

texture, vascular patency, and bleeding on incision; however,

in many cases it is difficult to determine tissue viability with

these techniques (see page 501 for a discussion of methods

for determining tissue viability). Necrotic tissue may range

in color from gray-green to black and often feels thin. A fullthickness incision can be made into the suspected necrotic

tissue to assess arterial bleeding. Intravenous fluorescein dye

has not proved to be an accurate method of determining

gastric viability in dogs with GDV. Generally, if you question

the viability of the gastric tissue, remove it or invaginate it.

Failure to remove or invaginate necrotic tissue may result in

perforation, peritonitis, and death. Melena is commonly

observed for a few days after gastric invagination.

NOTE Do not use mucosal color to predict gastric

viability; the mucosa is commonly black in dogs with

GDV because of vascular obstruction. Damage to the

mucosa may predispose these animals to gastric

ulceration.

To remove the greater curvature of the stomach, ligate

branches of the left gastroepiploic vessels or short gastric

vessels (or both) along the section of the stomach to be

removed (Fig. 20-69). Excise the necrotic tissue, leaving a

margin of normal, actively bleeding tissue to suture. Close

the stomach in a two-layer inverting pattern using 2-0 or 3-0

absorbable suture (e.g., polydioxanone, polyglyconate).

Incorporate the submucosa, muscularis, and serosal layers

in a Cushing or simple continuous pattern in the first layer.

Then use a Cushing or Lembert pattern to invert the serosa

and muscularis over the first layer. As an alternative, you

may use a thoracoabdominal (TA) stapling device to close

the incision. To invaginate necrotic tissue, use a simple continuous suture pattern followed by an inverting pattern. Place

sutures in healthy gastric tissue on both sides of the tissue

that is to be invaginated, bringing the healthy tissue over the

top of the necrotic tissue. Make sure the sutures are placed

in healthy tissues to prevent dehiscence.

Removal of neoplasia (see p. 494) or ulceration (see p.

490) of the greater or lesser curvature is similar to that

described for necrotic tissue. Most neoplasms in the gastric

body except for leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas have

metastasized by the time they are diagnosed. If the abnormal

tissue involves the dorsal or ventral aspect of the stomach,

an elliptic incision encompassing the lesion and some

FIG 20-68. Invagination of necrotic gastric tissue.

adjacent normal tissue is used. Closure is as for a simple

gastrotomy. Occasionally the extent of the lesion requires

resection of both the dorsal and ventral walls of the stomach.

In such cases, ligate branches of the right and left gastric

artery and vein (lesser curvature) and left gastroepiploic

artery and vein (greater curvature) and remove the omental

attachments. After removal of the suspect tissues, perform a

two-layer end-to-end anastomosis of the stomach. If the

luminal circumferences are of disparate size, the larger circumference can be partly closed using a two-layer suture

pattern (see Fig. 20-70, B). Close the mucosa and submucosa of the dorsal surface of the stomach in a simple continuous pattern using 2-0 or 3-0 absorbable suture (e.g.,

polydioxanone, polyglyconate), then with the same suture

close the ventral aspect. Suture the serosa and muscularis

layers in an inverting pattern (e.g., Cushing or Lembert).

Temporary Gastrostomy

Temporary gastrostomy is used to decompress the stomach

and occasionally is indicated in dogs with GDV until more

definitive surgery can be performed but is rarely done. For

a description of the technique, see Small Animal Surgery,

second edition.

Pylorectomy with

Gastroduodenostomy (Billroth I)

Removal of the pylorus and gastroduodenostomy

is indicated for neoplasia (see p. 494), outflow obstruction

caused by pyloric muscular hypertrophy (see p. 488), or

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Automorphic Representations and L-Functions For The General Linear Group - Volume 2cDocument210 pagesAutomorphic Representations and L-Functions For The General Linear Group - Volume 2cluisufspaiandreNo ratings yet

- MechanismDocument17 pagesMechanismm_er100No ratings yet

- Synetek Controls Inc.: Ds1-S: Installation InstructionsDocument2 pagesSynetek Controls Inc.: Ds1-S: Installation Instructionsdgd_electromecNo ratings yet

- MRP Format MbaDocument6 pagesMRP Format Mbasankshep panchalNo ratings yet

- Hazop Recommendation Checked by FlowserveDocument2 pagesHazop Recommendation Checked by FlowserveKareem RasmyNo ratings yet

- Thick Seam Mining Methods and Problems Associated With It: Submitted By: SAURABH SINGHDocument13 pagesThick Seam Mining Methods and Problems Associated With It: Submitted By: SAURABH SINGHPrabhu PrasadNo ratings yet

- ATM ReportDocument16 pagesATM Reportsoftware8832100% (1)

- Aemses Sof Be LCP 2021 2022Document16 pagesAemses Sof Be LCP 2021 2022ROMEO SANTILLANNo ratings yet

- Telecomm SwitchingDocument49 pagesTelecomm SwitchingTalha KhalidNo ratings yet

- Liquid Air Energy Storage Systems A - 2021 - Renewable and Sustainable EnergyDocument12 pagesLiquid Air Energy Storage Systems A - 2021 - Renewable and Sustainable EnergyJosePPMolinaNo ratings yet

- Lecturer No 1 - Transformer BasicDocument1 pageLecturer No 1 - Transformer Basiclvb123No ratings yet

- AESCSF Framework Overview 2020-21Document30 pagesAESCSF Framework Overview 2020-21Sandeep SinghNo ratings yet

- ClarifierDocument2 pagesClarifierchagar_harshNo ratings yet

- Augustine and The Devil Two BodiesDocument12 pagesAugustine and The Devil Two BodiesAlbert LanceNo ratings yet

- Release emotions with simple questionsDocument10 pagesRelease emotions with simple questionsDubravko ThorNo ratings yet

- trac-nghiem-ngu-am-am-vi-hoc-tieng-anh-đã chuyển đổiDocument18 pagestrac-nghiem-ngu-am-am-vi-hoc-tieng-anh-đã chuyển đổiNguyễn ThiênNo ratings yet

- Srimanta Shankardev: Early LifeDocument3 pagesSrimanta Shankardev: Early LifeAnusuya BaruahNo ratings yet

- Corporate Subsidies On A Massive ScaleDocument2 pagesCorporate Subsidies On A Massive ScaleBurchell WilsonNo ratings yet

- Vedic Astrology OverviewDocument1 pageVedic Astrology Overviewhuman999100% (8)

- Vikash Kumar: 1. Aunico India May 2018Document4 pagesVikash Kumar: 1. Aunico India May 2018Rama Krishna PandaNo ratings yet

- Food 8 - Part 2Document7 pagesFood 8 - Part 2Mónica MaiaNo ratings yet

- On MCH and Maternal Health in BangladeshDocument46 pagesOn MCH and Maternal Health in BangladeshTanni ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Implementing a JITD system to reduce bullwhip effect and inventory costsDocument7 pagesImplementing a JITD system to reduce bullwhip effect and inventory costsRaman GuptaNo ratings yet

- Booklet English 2016Document17 pagesBooklet English 2016Noranita ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Provisional List of Institutes1652433727Document27 pagesProvisional List of Institutes1652433727qwerty qwertyNo ratings yet

- 2000 T.R. Higgins Award Paper - A Practical Look at Frame Analysis, Stability and Leaning ColumnsDocument15 pages2000 T.R. Higgins Award Paper - A Practical Look at Frame Analysis, Stability and Leaning ColumnsSamuel PintoNo ratings yet

- Specification: F.V/Tim e 3min 5min 8min 10MIN 15MIN 20MIN 30MIN 60MIN 90MIN 1.60V 1.67V 1.70V 1.75V 1.80V 1.85VDocument2 pagesSpecification: F.V/Tim e 3min 5min 8min 10MIN 15MIN 20MIN 30MIN 60MIN 90MIN 1.60V 1.67V 1.70V 1.75V 1.80V 1.85VJavierNo ratings yet

- Etoposide JurnalDocument6 pagesEtoposide JurnalShalie VhiantyNo ratings yet

- CFC KIDS FOR CHRIST 2020 FINAL EXAMDocument13 pagesCFC KIDS FOR CHRIST 2020 FINAL EXAMKaisser John Pura AcuñaNo ratings yet

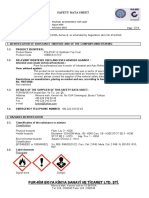

- Polifur 1K Synthetic Top Coat MSDS Rev 2 ENDocument14 pagesPolifur 1K Synthetic Top Coat MSDS Rev 2 ENvictorzy06No ratings yet