Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Integrated E-Strategy Model For Increasing Competi...

Uploaded by

HadiBiesOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Integrated E-Strategy Model For Increasing Competi...

Uploaded by

HadiBiesCopyright:

Available Formats

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.

9/10, 179-208

An Integrated e-Strategy Model for

Increasing Competitive Performance

of Manufacturing Small and Medium

Sized Enterprises in Kazakhstan

Tayfun TURGAY

Prof. Dr., Department of Business Administration, Faculty of

Business and Economics, Eastern Mediterranean University

Rassim KARBOV

R. Asst., Department of Business Administration, Faculty of

Business and Economics, Eastern Mediterranean University

Abstract

In todays hyper-competitive markets, manufacturing SMEs try to

gain advantage by deploying surprise strategies and use of

technology through which they secure the advantage of introducing

goods to the market prior to their competitors. Meanwhile,

electronic commerce offers a rich array of opportunities to improve

manufacturing SMEs competitive performance. Choosing a

particular e-commerce application is a strategic decision that must

be made in the context of the companies strategies. Therefore, the

primary purpose of this study is to explore the essence of generic

competitive, growth and e-commerce strategies in enhancing the

competitiveness of manufacturing SMEs in Kazakhstan through

integrated E-Strategy Model. The primary data was collected

through a questionnaire distributed to the managers of 80

manufacturing SMEs in Kazakhstan. The hypothesized

relationships were tested by single and multiple regression analysis,

179

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

using SPSS.13. The studys results demonstrated that business and

e-commerce strategies were the most important factors affecting

the firm competitiveness.

Keywords: E-commerce, e-commerce strategies, business

strategies, manufacturing small and medium sized

enterprises, Kazakhstan, firm competitiveness, estrategy model.

Introduction

Small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) are often credited as

agents of industrial change and innovation and vehicles for

employment generation, wealth creation and economic growth.

According to the industrial statistics of market economies, the

prolific small and medium businesses economy represents about 99

percent of all enterprises and accounts for approximately half of

private sector employment. However, SMEs operate in a highly

competitive environment where risk and uncertainty are an integral

part of its operations.

Globalization and technological innovations have changed

the way that manufacturing SMEs operate. These changes, despite

the enormous benefits they brought, have also made the

environment more competitive, therefore increasing the

manufacturing SMEs exposure to various risks of loosing

competitiveness and profitability. The need arose to manage these

new types of risks so that manufacturing SMEs could continue to

effectively and efficiently operate in a competitive environment, at

the same time gaining the competitive advantage and ensure their

profitability.

In order to preserve its competitiveness and overall

performance high, manufacturing SMEs should set sound effective

growth and competitive strategies in the presence of dynamic

environment. Recent advances in technology are changing the way

companies operate, availability and falling costs of personal

computers have had a major effect on the ability of manufacturing

SMEs to compete in electronic commerce world.

180

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

Therefore, this study demonstrates an integrated E-Strategy

Model which aims to measure generic competitive, growth and ecommerce strategies in enhancing manufacturing SMEs

competitiveness in Kazakhstan. It also sets out to prove crucial

parts of the integrated model in order to demonstrate its reliability

and validity.

This study is carried out in the manufacturing industry of

SME sector in Kazakhstan. The SME sector has been chosen

because it plays a very important role in society, market and

economy.

Socio-Economic Environment of Kazakhstan

The Republic of Kazakhstan extends from the Volga River in the

west to the Altai Mountains in the east, from the Siberian plain in

the north to the Central Asian deserts in the south. In 1991

Kazakhstan declared independence from the USSR, and was

redesignated the Republic of Kazakhstan. In that year the country

was formally recognized as a co-founder of the Commonwealth of

Independent States. Kazakhstan is the second largest country in the

region, the total area is 2,724,900 sq km, over four-fifths the size of

India (but with only 2% of the population). The total population at

1 January, 2005 was estimated to be 15,074,200.

In 2004, according to estimates by the World Bank, (2004)

Kazakhstans gross national income (GNI) was US $33,780

million (m). During 19952004, it was estimated, the population

decreased at an average annual rate of 0.8%, while gross domestic

product (GDP) per head increased, in real terms, by an average of

6.8% per year. Throughout 19952004, overall GDP has increased,

in real terms, at an average annual rate of 6.0% and real GDP

increased by 9.4% in both 2004 and 2005.

Industry (including mining, manufacturing, construction,

and power) contributed 37.1% of GDP in 2004, according to

provisional figures. The sector provided 17.2% of total

employment in 2003. Measured by the gross value of output, the

principal branches of industry in 1997 were the fuel industry

(accounting for 27.7% of the total), metal-processing (23.9%),

181

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

food-processing (15.4%) and electrical power generation (14.1%).

Industrial GDP increased, in real terms, at an average annual rate

of 7.2% in 19952004. According to ADB figures, the GDP of the

sector increased by 10.1% in 2004 and by 4.6% in 2005.

Manufacturing provided 10.2% of employment in 1998, and an

estimated 15.6% of GDP in 2004. The GDP of the manufacturing

sector increased at an average annual rate of 6.4% in 19952004.

Definition and Essence of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises

According to the World Bank Group, (2001) definition enterprises

that employ less than 10 workers and generate revenues less than

100 thousands $US are very small (micro); enterprises that employ

10 to 50 workers and generate revenues between 100-3000

thousands $US are small sized; and the enterprises that have 50 to

300 employees and generate revenues between 3000-15000

thousands $US are medium sized. Although number of SME

employees may vary from place to place. For example, SMEs in

Canada are characterized with a number of employees less than

500, whereas this number would represent a large sized business.

In European Union, the classification number varies from 250 in

the medium sized businesses, and with employees fewer than 50 in

small sized businesses.

SMEs represent a significant importance and play a crucial

role in the national economy (Desouza and Avazu, 2006). The

importance of standardized mass production lost its weight already

some time ago (Jenner and Hubner, 1992). Flexible structure of

SMEs contributed to the progressive indicators a great deal, thus

exuding a high level of employment potential and displaying

advantageous outcomes that provide stability and competitiveness,

exert assistance to larger industrial enterprises, pay close attention

to customer care and their needs, faster in adapting new

technologies and creative methods of management, and establish

an indispensable insurance for the stability and growth in the

countries economies. In a natural way a small or medium

enterprise is closer to the contemporary vision of a new, flat and

lean, horizontal company (Womack, Jones and Ross, 1990).

182

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

Furthermore, for politicians and governments the SME sector is

important first of all due to the fact that it can replace the

government in the difficult task of job creation, which is one of the

most main issues for the countrys economy. Another important

consideration for the governments is the potential for additional

fiscal income creation by the SME sector. According to the data

provided by Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development (OECD), SMEs comprise about 95 percent of

enterprises in a nation, thus employing 60-70 percent of workforce.

In Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation member economies, SMEs

reach up 90 percent of enterprises and employ between 32-84

percent of the workforce.

Manufacturing Small and Medium Sized Enterprises, Ecommerce and Business Strategies

The e-commerce establishes a very powerful path that gives new

alternatives and opportunities for the businesses to implement their

activities. According to Kalakota and Whinston, (1996) ecommerce has been defined as the buying and selling of

information, products, and services via computer networks.

The reliability of the e-commerce and its common aim by

various business representatives has helped many manufacturing

SMEs to implement their activities despite the many changes, and

barriers that come along the way. The relative size of the firms

enables manufacturing SMEs to be more adaptable and responsive

to changing conditions than large organizations (Grieger, 20003)

and to benefit from the speed and flexibility that the electronic

environment offers. The advantages of e-commerce participation

for manufacturing SMEs are mostly related to their ability to keep

pace with a changing business landscape. New information

technology (IT) has a changing behavior that entails the following:

facilitated access to global markets, changes in production methods

and costs, enhances in communication, reduced transaction costs

and stimulated competition that resulted in new competitive

premises to SMEs from e-commerce application.

183

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

In the case of Ireland, firms have high expectations of

getting over physical barriers that are attributed to the geographical

location and remote distance from Europe. This example implies

that manufacturing SMEs have come to appreciation of the

valuable features of the e-commerce and its abilities to cross over

geographical distances, thus exerting positive and successful

progress and contribution to the growth outcomes.

Regarding e-commerce as a source of interactivity, Blattberg

and Deighton, (1991) argument that interactive computer systems

will introduce a fresh approach to customer relationship

management and point up the importance of competencies such as

communication.

The Internet represents a crucial point that contributes to

lowering barriers for new competitors. Without any huge

investments they can easily enter into e-commerce. As a matter of

fact, the e-commerce changes the basis of competition by adding

alterations to the products and the cost structure of manufacturing

SMEs. In addition, the use of the e-commerce reduces the

customers search cost by letting customer compare the prices.

Facilitation of an electronic integration of the supply chain

activities as well as facilitation of partnerships of generation of

strategic alliances network is another characteristic representative

to the features of the e-commerce for manufacturing SMEs.

Understanding of the Internet, networking and e-commerce

exhibits a considerable significance in determining the outcomes

and advantages contributing to buyer and seller relationships.

McGowan, (2001) gives the following examples and notes that

communication through the e-commerce helps manufacturing

SMEs to acquire a myriad of information that aids in comparing

the differences in functions and variables. Consequently possession

of information leads to knowledge perseverance transforming into

evaluation, and planning activities accordingly.

184

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

1. Business Strategies

Effective strategies have always leaded many companies to highperformance results. Researches have shown that a firms strategy

is the most important determinant of companys performance

(Heracleous, 2003). According to Shrader et al, (1984), Strategy

is the primary means of reaching the focal objective. The focal

objective is whatever objective is in mind at the moment. Strictly

speaking, it is literally meaningless to talk about strategy without

having an objective in mind. Viewed in this context strategy

becomes an integral part of the ends-means hierarchy. Strategy is

the direction and scope of an organization over the long term.

In changing world some companies perform better than their

rivals in terms of global, business, corporate and functional level

productivities due to implementation and capitalization of

strategies. However, an organizations strategy must be appropriate

for its resources, environmental circumstances, and core objectives.

The process involves matching the company's strategic advantages

to the business environment the organization faces. One objective

of an overall corporate strategy is to put the organization into a

position to carry out its mission effectively and efficiently.

1.1. Growth Strategies (Ansoffs product/market growth

matrix)

Based on the contemporary researches, many authors have

commented on the typical limitations of strategic alternatives such

as small market share and limitations of resources and skills to the

small firms (Carson, 1985). According to Storey and Sykes, (1996),

due to these limitations, not all strategies are typically suitable for

SMEs. Therefore, appropriate strategies are those that avoid direct

competition with bigger firms and contribute to the developments

of close customer relationships and new product versions. In the

specific language of Ansoffs Matrix, it has been suggested by

Perry, (1987) that for SMEs the most appropriate growth strategies

is therefore product development and market development.

Furthermore, Cravens et al., (1994) addressed that organizational

185

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

characteristics, strategic situation and entrepreneur motivations

would determine the choice of growth strategy for SMEs (p.247).

Igor Ansoff, (1965) contended that strategy is the integration

of five issued common thread: 1) product-market scope, 2)

competitive advantage, 3) growth vector, 4) internally generated

synergy, and 5) make or buy decisions.

Ansoffs product/market matrix has been amongst most

popular tools for growth strategy identification. The Ansoff matrix

helps to identify the companys product and market growth

strategy. The company is looking to grow through market

penetration, in other words, to expand profits by selling existing

products to the existing markets. Market development occurs when

a company seeks to sell its existing products into new markets. The

new markets could be geographically based either within the home

country or abroad alternatively the new market could be a new

market segment. A product development strategy entails

developing new products for sale in existing markets. This strategy

may require the development of new competencies and requires the

business to develop modified products which can appeal to existing

markets. Diversification is the name given to the growth strategy

where a business markets new products in new markets.

1.2. Competitive Strategies (Porters generic strategies)

Generic strategy is among the most popular business strategies that

have been based on assessing competitive environment and the

business's capabilities relative to other competitors. Researches

show that the link between organizational characteristics and the

generic business strategies of cost and differentiation is a recent

development. According to Porter, (1980) cost leadership;

differentiation and focus are ways businesses deal with the five

competitive forces, to create sustainable competitive advantage and

thereby higher returns. The formulation of competitive strategy

requires a completely different set of tools and methods of analysis

(Kotorov, 2001).

While considering Porters research, competitive advantage can

come from either having the lowest cost in the industry or from

186

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

possessing significant and desirable differences from competitors.

Furthermore, another important factor of Porters competitive

advantage is the broad and narrow scope of the product-market in

which the organization wishes to compete. The mix of these scopes

in terms provides the basis for Porters competitive strategies

which include cost leadership, differentiation and focus (cost and

differentiation).

Fundamentally, pure cost leadership strategies focus on

those variables that will allow the firm to achieve and maintain a

low cost position. The 'competitive price' set by the market place is

accepted. On the other hand, a business with a pure differentiation

strategy seeks to enhance the price element by offering customers

something they perceive as unique and for which they are willing

to pay a higher price. Differentiation usually requires incurring

higher costs but, if successful, these incremental costs will be less

than the incremental contribution attributable to the higher price.

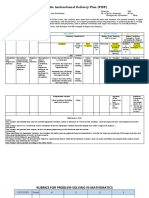

An integrated E-Strategy Model and Research Hypothesis

Given the fact that the number of SMEs is increasing every year in

Kazakhstan, they fail to keep their competitive position and

performance in the market (Tokaev, 2006). Therefore, the purpose

of this study is to exhibit and test a model that explores the essence

of business and e-commerce strategies in enhancing the perceived

competitiveness of manufacturing SMEs in Kazakhstan. Herein, an

application of E-Strategy Model is being made in order to show

how manufacturing SMEs can shift from traditional way of doing

business and increase their perceived competitiveness.

The main research question that investigated by this study is:

How generic competitive, growth and e-commerce strategies have

an impact on perceived competitiveness of manufacturing SMEs in

Kazakhstan?

The question above is mostly attributed to the components of

strategic management and e-commerce that will serve as a guide to

the empirical investigations of an integrated E-Strategy Model,

as depicted in (Figure 1). The integrated model is based on the

theoretical framework that explicated by other studies.

187

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

Figure 1 An integrated E-Strategy Model

In management literature, different studies have been focused on

the resource-based view of strategy and have argued that

competitive advantage and performance arises from distinctive

organizational capabilities (Peteraf, 1993). This view suggests that

competitive advantage and performance results are a consequence

of a firm-specific resources and capabilities.

Another literature suggests that one of the most effective intends of

achieving competitive performance is by using firms capabilities

(Fleisher and Bensoussan, 2003).

Resources such as: stocks of knowledge, physical assets, human

capital, and other tangible and intangible factors that a business

owns, enable a firm to achieve a greater efficiency and therefore

lower costs, increased quality and the possibility of greater market

share and profitability (Collis, 1994). Furthermore, distinctive

capabilities provide strategy directions by enabling a firm to take

188

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

advantage of its external opportunities and to minimize the threats

that it faces (Dess and Lumpkin, 2003).

ORegan and Ghobadian, (2004) examined that distinctive

capabilities (delivering a broad product range, advertise the

product and service, distribute products broadly, making rapid

design changes, deliver products quickly and offer consistent

quality) have a close relationship with generic competitive and

growth strategies. This indicates that the firms surveyed view

organizational capabilities as an integral part of the strategic

process. It could be argued that SMEs use their distinctive

organizational capabilities as the basis of their strategic direction.

Based on proceeding, the first two hypotheses can be proposed as:

H1: Distinctive Organizational Capabilities are associated with the

factors used to craft Generic Competitive Strategies.

H2: Distinctive Organizational Capabilities are associated with the

factors used to craft Growth Strategies.

In order to pursue sustainable e-commerce strategies, the

entrepreneur should take a systemic view of the critical success

factors which have already been explained in chapter two. Each of

them is dynamically linked with others and arises from the

accumulation and depletion processes affecting strategic assets. For

instance, in order to attain a firm competitiveness through ecommerce strategies based on the interaction factor, entrepreneurs

may foster those processes enlarging the business customer base.

At a consequence, the development of an interaction is achieved to

the prejudice of control and brand image in the long run.

Accordingly, to manage Internet-based growth strategies properly,

it is crucial to foster decision makers learning about effective

presentation of products and its product to price sensitivity over the

Internet. Furthermore, the higher the product scope, the higher will

be web-site attractiveness while applying e-commerce strategies

(KITE, 1999). It is therefore can be hypothesized that:

H3: The effective presentation of a product offered over the

Internet will have a positive impact on e-commerce strategy

implementation.

189

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

H4: The quality and usability of the Web Site is positively related

to e-commerce strategy implementation.

H5: Clearly defined processes of the company exert a positive

influence on e-commerce strategy implementation.

H6: Relationship building with stakeholders is positively related to

e-commerce strategy implementation.

H7: Brand name of a company and its products will significantly

influence e-commerce strategy implementation.

H8: Overall motivation for using the internet and will to innovate

will have a positive impact on e-commerce strategy

implementation.

H9: Sensitivity of a product to price competition on the internet

will have an effect on overall e-commerce strategy

implementation.

Earlier it has been mentioned that companies can achieve

competitiveness essentially by differentiating their products and

services from those of competitors and through low costs (Lynch,

2003). Choosing a particular e-commerce application is a strategic

decision that must be made in the context of the companys

competitive strategy (Lanckriet and Heene, 1999). The nature of

the e-commerce makes it easier for buyers and sellers to search,

meet, compare prices and negotiate and thereby helps in reducing

transactional costs (Berthon et al.., 2003).

Research by Pearson, (1999) shows that e-commerce

strategies significantly support generic competitive strategies in a

way of achieving cost leadership, differentiation and focus.

Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H10: E-commerce strategies have a positive impact on supporting

generic competitive strategies.

The Ansoff Matrix as growth strategies presents the product and

market choices available to an organization. It is argued that ecommerce strategies are used to sell more existing products into

existing products. E-commerce strategies can increase awareness

of a firm within the industry by pursuing market penetration

(Murphy, R and Bruce, M. 2003). Moreover, e-commerce

strategies facilitate market development. For instance, Amazon

190

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

initially used this as a growth strategy by taking their existing ecommerce strategy of book in the US market and developing it for

the UK. Hereby, e-commerce has facilitated the development of

new products and services (Murphy, R and Bruce, M. 2003).

According to McDonald, (2000) e-commerce helped firms to reach

their growth strategies by developing new products/services and

introducing them to new market segments in a way of pursuing the

diversification. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

H11: E-commerce strategies facilitate the implementation and

achievement of growth strategies.

E-commerce offers a rich array of opportunities to improve

business performance. An empirical study by Straub and Klein,

(2001) identified that e-commerce strategies benefited companies

on cutting costs and rising productivity, accessing new customers

and markets, and gaining sustainable competitive advantage by

attempting to achieve a complete integration of e-commerce into

the companys overall business strategy.

Another research shows that e-commerce strategies have great

impact on firms sales growth and profitability (Karagozoglu and

Lindell, 2004). Therefore, it can be hypothesized that:

H12: E-commerce strategies have a positive impact on perceived

firms competitiveness.

Methodology

Mainly, the descriptive statistics used to measure the demographic

variable and reliability, correlation and regression analysis for

testing the reliability and credibility of the hypotheses.

Hypothesized relationships are tested by using Statistical Package

for Social Sciences (SPSS 13).

1. Study Setting and Sample

The study is carried out in Kazakhstan amongst the managers of

manufacturing SMEs. The main aim of this study as previously

explained is to exhibit and test a model that explores the essence of

191

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

business and e-commerce strategies in increasing overall

manufacturing SMEs competitiveness in Kazakhstan. Basically, an

application of E-Strategy Model is being made in order to show

how manufacturing SMEs can shift from traditional way of doing

business and increase their competitiveness.

The company managers were the samples ranging from

Managing Director, Financial Manager, IT Manager, Marketing

Manager and Operation Manager Positions in Kazakhstan.

2. Questionnaire and Measures

According to survey structure, each manufacturing SME manager

was requested to answer the questionnaire specific for his/her

company. The method of obtaining information from managers

was based on asking opened-end and closed-end questions.

Two types of questionnaires were used in this study. These

questionnaires were administered to the target managers of

manufacturing SMEs.

The questionnaire was containing main five parts. The first

part had variables that explored managers age, gender, educational

level, position and how long they had been at the present position

within the company. The second part of the questionnaire tried to

explicate general information about the company such as: number

of employees, foundation year, ownership type, city of

headquarters, establishments outside of country and involvement in

foreign trade activity, number of PCs, length of connection to

Internet and web site availability within the firm. Furthermore, this

section purposed to identify a utilization of strategic planning,

capabilities, and generic competitive and growth strategies. The

initial positive affect of generic competitive and growth strategies

to e-commerce strategies were measured on a five point likert scale

ranging from 1= Definitely Used to 5= Definitely Not Used.

In the third section of the questionnaire, e-commerce strategies

were measured on a scale ranging from 1= Frequent Use to 3=

Never Use. In part four, Strategic value of e-commerce on

perceived firms competitiveness was measured on a scale ranging

from 1= Strongly Agree to 5= Strongly Disagree and finally,

critical success factors affecting overall e-commerce performance

192

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

was also measured on a 5 point scale ranging from 1= Strongly

Agree to 5= Strongly Disagree.

6.3. Sample

Total of 80 questionnaires were distributed to managers of

manufacturing SMEs and 80 were collected. This shows the

response rate of 100%. The majority of respondents (72.5%) were

female and 27.5% were male. The age of the respondents was

ranged between 18 and 29, totaled 38.8%; 30-59, totaled 53.7%;

and 60 and above, totaled 7.5%. Based on data, we can observe a

slight skewness towards middle aged respondents.

The majority of respondents (48.7%) were holding four year

university degree, 37.5% had a masters degree, 5% had a PhD

education and 8.8% of respondents had two year university degree.

Most of the respondents (30.0%) as depicted in table 1 were

holding Managing Director positions, 28.7% IT Manager positions,

16.3% Marketing Manager Positions, 15.0% Operation Manager

Positions and 10.0% Finance Manager positions.

Further detailed information regarding respondent demographics

and company profiles are presented in tables 1, 2 and 3.

193

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

Table 1 Demographic Breakdown of the Sample Study

Frequency

Valid Percent (%)

Gender

Female

Male

58

22

72.5

27.5

Age

18-29

30-59

31

43

38.8

53.7

60+

7.5

Education

Two year university

Four year university

Master

Doctorate

7

39

30

8.8

48.7

37.5

5.0

Position

Managing Director (GM)

Finance Manager

IT Manager

Marketing Manager

Operation Manager

24

8

23

13

12

30.0

10.0

28.7

16.3

15.0

Years in position

Less than 10

More than 10

49

31

61.2

38.8

194

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

Table 2 Corporate Breakdown of the Sample Study

Frequency

Valid Percent (%)

Number of employees

Less than 10 (Micro Enterprises)

10-49 (Small Enterprises)

50-300 (Medium Enterprises)

0

33

47

0.0

41.3

58.7

Type of ownership

Sole Proprietorship

Family

State Enterprise

Other

7

15

36

22

8.8

18.7

45.0

27.5

Foundation year of a firm

1-10

10+

35

45

43.7

56.3

City of firm headquarters

Almaty

Astana

Taraz

Karaganda

Shymkent

Abroad

Other

38

8

15

3

4

5

7

47.5

10.0

18.7

3.8

5.0

6.3

8.7

195

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

Table 3 Corporate Breakdown of the Sample Study

Frequency

Valid Percent (%)

Establishment outside of country

Yes

No

31

49

38.8

61.2

Sales from outside of home country

Less than 10%

10-50%

More than 50%

46

29

5

57.5

36.2

6.3

Purchases from outside of

country

Less than 10%

10-50%

More than 50%

51

28

1

63.8

35.0

1.2

Number of PCs in the firm

Less than 5

5-100

100+

12

30

38

15.0

37.5

47.5

Length of connection to Internet

Not available

Less than 1 year

2 years

3 years

More than 3 years

12

4

8

17

39

15.0

5.0

10.0

21.3

48.7

Web site availability

Yes

No

50

30

62.5

37.5

home

Strategic decision

Owner

16

20.0

Manager

Family member

Other

35

13

16

43.8

16.2

20.0

Based on sample observations in figure 2, it can be observed that

72.5% of manufacturing SMEs agreed that e-commerce increases

their competitive position. It is also obvious that more than 70% of

196

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

manufacturing SMEs accept that e-commerce improves product

differentiation and organizational communication. However,

according to the sample, e-commerce did not contribute on

increasing the profits of the companies.

Figure 2 Strategic importance of E-commerce for perceived firms

competitiveness

4. Hypothesis Testing Results

The psychometric properties used for assessing the measures were

reliability coefficients, single and multiple regression analysis and

correlation coefficients. The reliability test evaluated the internal

consistency of the scale and the single and multiple regression tests

197

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

showed the relationship between the measures and the dependent

variable. The correlation coefficients were used to show the

association between the measures.

4.1 Reliability Tests

To check the internal consistency among the variables and with the

scale, reliability tests were conducted to ensure the measurement

items were reliable, in other words, the items mostly reflected true

scores rather than the error on the scales and the items. Table 4

presents the reliability test for each variable in the survey

conducted on managers.

Table 4 Relaibility Coefficients of Business and E-commerce strategies on

Perceived Firms Competitiveness

Measure

DOC 1

CS

GS

ECS

CSF

FCOM

Chronbach's alpha

0.79

0.82

0.70

0.89

0.71

0.76

According to Nunnally, (1978) the coefficients that equal to or

above 0.70 are acceptable indicators of reliability. From table 4, all

the Chronbachs alpha scores were within this range.

4.2 Regression Tests

In this study, three single and two multiple regression tests were

conducted to measure integrated E-Strategy Model.

Formula 1. CSpredicted = .30 + .40DOC

Formula 2. GSpredicted = .70 + .52DOC

1

The list of abbreviations can be found in appendix.

198

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

Formula 3. ECSpredicted = 1.10 + .25CSF1 + .41CSF2 + .35CSF3

+ .10CSF4 + .30CSF5 + -.30CSF6 + -.50CSF7

Formula 4. ECSpredicted = .92 + .33CS + .42GS

Formula 5. FCOMperceived = 1.64 + .26ECS

The results of the tests are presented through tables 5 and 6.

Table 5 ANOVA of the Regression Test of the Survey

ANOVA

Model

1

2

3

4

5

Regression

Residual

Regression

Residual

Regression

Residual

Regression

Residual

Regression

Residual

Sum of Squares df Mean Square F

Sig.

8.708

46.816

2.229

5.987

3.696

4.667

2.734

5.630

1.236

17.095

14.509

.000

29.043

.000

8.146

.000

18.694

.000

5.638

.020

1

78

1

78

7

72

2

77

1

78

8.708

.600

2.229

.077

.528

.065

1.367

.073

1.236

.219

One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the regression test as

depicted in table 5 shows that the linear combination of the

dimensions is statistically significant. The F values are 14.509,

29.043, 8.146, 18.694 and 5.638 with the p values of 0.000 and

0.020. The regression shows the explained portion of the variance

and the residual shows the unexplained portion of the variance.

By summarizing table 6, we can say that B shows the

constant and the coefficients for the regression equation that the

measures predict. The standard error is the standard deviation of

the B values and it is a measure of stability or sampling error of the

B values. Beta is the standardized regression coefficients. Thus

they are the z scores for the independent variables. T is a test to

show that a particular correlation is statistically significant. The

significance of t shows the probability that the independent

199

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

variables will occur. As shown in table 6, most of t-values of

variables were significant, which is (>2.00).

Table 6 Coefficients of the Regression Test of the Survey

Coefficients

Mode

1

B

(Constant) .302

DOC

Std. Error Beta

Sig.

.499

.606

.546

1.247 .327

(Constant) .712

.178

DOC

.117

.631

.396

3.809 .000

3.992 .000

.521

(Constant) 1.110 .139

5.389 .000

7.959 .000

CSF1

.011

.050

.025

.226

.822

CSF2

.0184 .063

.417

2.914 .005

CSF3

.193

.058

.349

3.303 .001

CSF4

.034

.031

.113

1.098 .276

CSF5

.138

.043

.312

3.219 .002

CSF6

.154

.075

.310

2.057 .043

CSF7

-.016

.031

-.051

-.519

.605

(Constant) .924

.179

5.466 .000

CS

.127

.037

.326

3.452 .001

GS

.428

.095

.424

4.489 .000

(Constant) 1.645 .313

ECS

.384

.162

5.246 .000

.260

2.375 .020

Mode 1 and 2 of single regression tests show how well distinctive

organizational capabilities contribute to competitive and growth

strategies. From the table above, it is indicated that there is a

probability of DOC to occur, p= 0.000. Which means that

hypothesized are statistically significant (<0.05). Furthermore,

200

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

mode 3 of regression tests show the possible effect of critical

success factors on performance of e-commerce strategies. By

summarizing table 6, it can be seen that there is no probability that

CSF1, CSF4 and CSF7 will occur. The significance of their t

values are 0.226, 1.098 and

-0.519 respectively. There is also no probability that the

outcome dimensions would occur. The significance of their t

values are 0.822, 0.276 and 0.605 respectively. However, there is a

strong probability that CSF2, CSF3, CSF5 and CSF6 will occur.

Moreover, mode 4 of regression tests show the possible effect of

competitive and growth strategies on performance of e-commerce

strategies. As shown in table 6, it can be seen that there is a

probability that CS and GS will occur. The significance of their t

values is 3.452 and 4.489 respectively. The significance of their t

values is 0.001 and 0.000 respectively. Lastly, mode 5 of

regression test shows whether e-commerce strategies significantly

affect perceived firms competitiveness. From table 6, it can be

seen that there is a probability that ECS occur. The significance of

their t values is 2.375 and significance of its t value is 0.020.

4.3. Correlation Analysis

A correlation analysis was performed in order to find out the

associations between these measures and perceived firms

competitiveness. The correlations are shown in table 7 as follows:

201

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

Table 7 Correlation of variables

Variable

GS

Sig. (2-tailed)

CS

Sig. (2-tailed)

FCOM GS CS

.277*

.013

.131 .146

.248 .197

DOC

Sig. (2-tailed)

ECS

Sig. (2-tailed)

CSF1

Sig. (2-tailed)

CSF2

.124

.273

.260*

.020

.063

.579

-.018

.521*

.000

.472*

.000

.171

.129

.242*

DOC ECS CSF1 CSF2 CSF3 CSF4 CSF5CSF6

.396**

.000

.388* .408*

.000 .000

.156 .164 .292**

.168 .146 .009

.118 .142 .430* .517**

Sig. (2-tailed) .872

CSF3

.139

.031 .296

.361* .194

.209 .000 .000

.266* .526* .382**.414**

Sig. (2-tailed)

CSF4

Sig. (2-tailed)

CSF5

Sig. (2-tailed)

.219

.096

.399

.212

.059

.001 .084

.081 .019

.475 .870

.379**.125

.001 .270

.017 .000

.013 .151

.907 .180

.290**.454*

.009 .000

CSF6

.067

Sig. (2-tailed) .557

.138 .004

.222 .969

.116

.304

CSF7

Sig.

tailed)

N

.019

.050 -.050 .005

.256* .506**.768**.412**.401**.201

.022 .000 .000 .000 .000 .074

.080 .227* .254* .152 .014 .242* .357**

.865

80

.661 .658

80

80

.043

.481

80

80

(2.967

80

.000 .000

.406**.325**0.85

.000 .003 .452

.128 .224* .356**-.038

.257 .046 .001 .738

.023

.179

80

80

.904

80

.031 .001

80 80

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

From the table above, it can be seen that most of the variables were

positively correlated with each other. Growth and e-commerce

strategies were positively correlated with dependent variable, and

they were statistically significant. Growth and e-commerce

strategies have a positive impact on perceived firms

competitiveness.

Conclusion

In the presence of dynamic environment and competitive world,

small and medium sized enterprises in Kazakhstan face

202

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

competitive pressure from larger companies which reduces

manufacturing SME competitiveness.

In todays hyper-competitive markets as previously

remarked, companies try to gain advantage by developing surprise

strategies through which they secure the advantage of introducing

goods and services to the market prior to their competitors.

The primary purpose of this study was to explore the essence of

selected business and e-commerce strategies in enhancing the

perceived competitiveness of manufacturing SMEs in Kazakhstan

through integrated E-Strategy Model.

The findings of this study show that (H1) is accepted. Based

on the regression analysis and the correlation test, it is obvious that

distinctive organizational capabilities that firm possess positively

affect the improvement and implementation of generic competitive

strategies. This means that distinctive organizational capabilities

are the key factors in designing and applying successful generic

competitive strategies.

The second hypothesis (H2) is also accepted. Distinctive

organizational capabilities are positively associated with the factors

used to craft growth strategies. This means that the distinctive

organizational capabilities that firm owns have a great impact on

scheduling growth strategies by providing directions to market

penetration, market development, product development and

diversification of firms products. There is a strong correlation

between distinctive capabilities and growth strategies, which

supports the fact that there is a mutual relationship between these

two variables.

(H3) is not accepted. The results of the tests show that the

effective presentation of a product offered by a firm over the

Internet does not have a positive impact on overall e-commerce

strategy implementation. This might be due to insufficient number

of internet subscribers in Kazakhstan. No researches were found

related to this concern.

According to correlation test results (H4) and (H5) are

accepted. This means that the quality and usability of web site and

clearly defined processes of the company are positively related to

e-commerce strategy implementation.

203

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

Whats more, (H6) is not accepted. The test results show that there

is no significant correlation between relationship buildings with

firm stakeholders and e-commerce strategies. According to Cragg

and King, (1993) the reason behind that could be the following:

lack of knowledge competency and skill level of business operators,

lack of e-commerce readiness in some industry sectors, lack of

ambitiousness for extracting benefits and understanding of ecommerce. Therefore, we can say that e-commerce strategies are

not affected by stakeholder relationship building behavior of a

company.

However, (H7 and H8) are accepted. The correlation results

present that brand name of a company and its products and overall

motivation for using the internet and will to innovate have a

positive impact on e-commerce strategy implementation. Moreover,

(H9) is not accepted the statistical results have shown that

sensitivity of a product to price competition on the internet does

not affect overall e-commerce strategies. There wasnt any

significant correlation between these two variables. The reason can

be the same as in hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis (H10) is accepted. Based on the test results, it

can be said that e-commerce strategies have a positive impact on

supporting and achieving competitive generic strategies which are

set by a firm. The e-commerce strategies are significantly

correlated and have a great effect on the growth strategies. Thus,

(H11) is accepted.

Lastly, there is evidence based on correlation test results

showing that, successful e-commerce strategies have positive

impact on overall perceived firms competitiveness. Therefore, we

can conclude that (H12) is accepted.

204

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

Appendix

List of Abbreviations

Dimensions

Distinctive

Organizational

Capabilities

(DOC)

Critical Success

Factors (CSF)

Competitive

Strategies (CS)

Growth Strategies

(GS)

E-commerce

Strategies (ECS)

Perceived Firms

Competitiveness

(FCOM)

Variables

Employee Dedication

Technology

Know-how

Resources

Content

Convenience

Control

Interaction

Brand Image

Commitment

Price Sensibility

Cost Leadership

Differentiation

Focus

Market Penetration

Product Development

Market Development

Diversification

E-mail

Browsing company homepages

Market and product research

Exchange of information with clients

Information search

Exchange of information with suppliers

Receiving orders from clients

Placing orders to suppliers

Intra-company communication

Medium of payment

Placing job recruitment advertisements

Video-conference

Overall competitive performance from

utilization of e-commerce strategies

205

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

Reference

ANSOFF, I. (1957), Strategies for diversification, Harvard

Business Review, September/October, p.114.

BERTHON, P., EWING, M., PITT, L. and NAUDE, P. (2003),

Understanding B2B and the Web: the acceleration of

coordination and motivation, Industrial Marketing

Management, Vol. 32 No. 7, pp. 553-61.

BLATTBERG, R.C. and DEIGHTON, J. (1991), ``Interactive

marketing: exploiting the age of addressability'', Sloan

Management Review, Fall, pp. 5-14.

CARSON, D.J. (1985), The evolution of marketing in small

firms, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 19, No. 5.

COLLIS, D.J. (1994), Research note: how valuable are

organizational capabilities? Strategic Management Journal,

Vol. 15 No.S2, pp. 143-52.

CRAGG, P.B., and King, M. (1993), "Small-firm computing:

Motivators and inhibitors," MIS Quarterly (17:1), pp 47-60.

CRAVENS, D.W., LUNSFORD, D.A., HILLS, G.E. and

LAFORGE, R.W. (1994), An agenda for integrating

entrepreneurship and marketing strategy research,

Marketing and Entrepreneurship: Research Ideas and

Opportunities, Greenwood, Westport, CT, pp. 53-235.

DESOUZA, M. and AVAZU, Y. (2006), Knowledge management

at SMEs: five peculiarities, Business Research, Chicago, IL,

USA, VOL. 10 NO. 1, pp. 32-43.

FLEISHER, C.S. and BENSOUSSAN, B.E. (2003), Strategic and

Competitive Analysis: Methods and Techniques for

Analyzing Business Competition, Prentice-Hall, Englewood

Cliffs, NJ.

GRIEGER, M. (2003), "Electronic marketplaces: A literature

review and a call for supply chain management research,"

European Journal of Operational Research (144), pp. 280294.

HERACLEOUS, L (2003), strategy and organization: Realizing

Strategic Management, International ed., Cambridge

University Press, pp.4

206

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

JENNER, R., and HUBNER, W. (1992), Complexity Based

Strategies for Restructuring Formerly Planned Economies,

Working Paper Series, School of Business, San Francisco

State University

KALAKOTA, R. and WHINSTON, A.B. (1996), Frontiers of

Electronic Commerce, Addison-Wesley, London.

KARAGOZOGLU, N. and LINDELL, M. (2004), Electronic

commerce strategy, operations, and performance in small

and medium-sized enterprises, Journal of Small Business

and Enterprise Development, Volume 11, pp. 290-301.

KITE (Knowledge and Information Transfer on Electronic

Commerce). (1999), Gazelles and Gophers: SME

Recommendations for Successful Internet Business.

European project publication. http://kite.tsa.de/.

KOTOROV, R.P (2001), The Strategy Wheel: A Method for

Analysis and Benchmarking for Competitive Strategy,

Competitive Intelligence Review, Vol. 12(3) 2130 (2001).

LANCKRIET, D. and HEENE, A. (1999), A competence-based

strategic management framework for introducing e-business

in small and medium-sized enterprises: a view of an

entrepreneur, post-conference publication, LPR, available

at: www.cbm.net.

LYNCH, R. (2003), Corporate Strategy, 3rd ed., Prentice Hall

Financial Times

McDONALD, T. (2000), Dont cry for Amazon e-commerce,

The Times.

McGOWAN, P. and ROCKS, S. (1995), ``Entrepreneurial

marketing networking and small firm innovation, Research

at the Marketing/Entrepreneurship Interface, The University

of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, pp. 43-54.

MURPHY, R. and BRUCE, M. (2003), Strategy, accountability, ecommerce and the consumer,

NUNNALLY, J.C. (1978), Psychometric Theory, 2nd edition,

McGraw Hill, New York, NY.

OREGAN, N. and GHOBADIAN, A. (2004), The importance of

capabilities for strategic direction and performance,

Management Decision, Vol.42 No. 2, pp. 292-312.

207

Review of Social, Economic & Business Studies, Vol.9/10, 179-208

PEARSON, G. (1999), Strategy in Action, Prentice Hall Financial

Times.

PERRY, C. (1987), Growth strategies: principles and case

studies, International Small Business Journal, Vol. 5, pp.

17-25.

PETERAF, M. A. (1993), The cornerstones of competitive

advantage: a resource-based view, Strategic Management

Journal, Vol. 14 No.3, pp.179-91.

PORTER, M.E. (1980), Competitive Strategy, Free Press, New

York, NY.

SHRADER, C.B., TAYLOR, L. and DALTON, D.R. (1984),

Strategic planning and organizational performance: a

critical appraisal, Journal of Management, Vol. 10 No. 2,

pp. 149-71.

STOREY, D.J. and SYKES, N. (1996), Uncertainty, innovation

and management, in Burns and Dewhurst (Eds), Small

Business and Entrepreneurship, Macmillan, Basingstoke, pp.

73-93.

STRAUB, D. and KLEIN, R. (2001), E-competitive

transformations, Business Horizons, Vol. 44 No. 3, pp. 3-12.

TOKAEV, K. (2006), Kazakhstan in the context of the geopolitics

of the Caspian, International Institute of Strategic Studies.

World Bank. (2004), Kazakhstan: Economic affairs. can be

accessed from http://www.europaworld.com/entry/kz.hist.

WORMACK, J.P., JONES, D.T. and ROSS, D. (1990), The

Machine Changed the World, MIT Press.

208

You might also like

- Carbon Emissions Embodied in Demand Supply Chains in CH - 2015 - Energy Economic PDFDocument12 pagesCarbon Emissions Embodied in Demand Supply Chains in CH - 2015 - Energy Economic PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 468 8694Document20 pages10 1 1 468 8694HadiBiesNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 463 5470 PDFDocument92 pages10 1 1 463 5470 PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- Lean Implementation in SMEs-2018Document19 pagesLean Implementation in SMEs-2018HadiBiesNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 461 7603 PDFDocument127 pages10 1 1 461 7603 PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- Bullwhip Effect Study in A Constrained Supply Chain - 2014 - Procedia Engineerin PDFDocument9 pagesBullwhip Effect Study in A Constrained Supply Chain - 2014 - Procedia Engineerin PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- Bullwhip Effect Mitigation of Green Supply Chain Opti - 2018 - Journal of Cleane PDFDocument25 pagesBullwhip Effect Mitigation of Green Supply Chain Opti - 2018 - Journal of Cleane PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Mko PDFDocument18 pagesJurnal Mko PDFAgatha MarlineNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Mko PDFDocument18 pagesJurnal Mko PDFAgatha MarlineNo ratings yet

- A Bi Level Programming Approach For Production Dis 2017 Computers IndustriDocument11 pagesA Bi Level Programming Approach For Production Dis 2017 Computers IndustriHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- Carbon Footprint and Responsiveness Trade Off - 2015 - International Journal of PDFDocument14 pagesCarbon Footprint and Responsiveness Trade Off - 2015 - International Journal of PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- Biomass Functions and Nutrient Contents of European Beech - 2018 - Journal of C PDFDocument13 pagesBiomass Functions and Nutrient Contents of European Beech - 2018 - Journal of C PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- Biofuel Supply Chain Design From Coffee Cut Stem Under Environmen - 2016 - Energ PDFDocument11 pagesBiofuel Supply Chain Design From Coffee Cut Stem Under Environmen - 2016 - Energ PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- Biomass Supply Chain Network Design An Optimization - 2016 - Industrial Crops A PDFDocument29 pagesBiomass Supply Chain Network Design An Optimization - 2016 - Industrial Crops A PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- Biomass Supply Chain in Asian and European C - 2016 - Procedia Environmental Sci PDFDocument11 pagesBiomass Supply Chain in Asian and European C - 2016 - Procedia Environmental Sci PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- Biomass Feedstock Supply Chain Network Design With Biomass Co - 2018 - Energy Po PDFDocument11 pagesBiomass Feedstock Supply Chain Network Design With Biomass Co - 2018 - Energy Po PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- A Business Process Re Design Methodology To Support 2015 International JournDocument12 pagesA Business Process Re Design Methodology To Support 2015 International JournHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- A Review On Lean Manufacturing Practices PDFDocument15 pagesA Review On Lean Manufacturing Practices PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- A Behavioral Experiment On Inventory Managem 2015 International Journal of PDocument10 pagesA Behavioral Experiment On Inventory Managem 2015 International Journal of PHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- Jordan Journal of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering (JJMIE), Volume 5, Number 6, Dec. 2011 PDFDocument103 pagesJordan Journal of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering (JJMIE), Volume 5, Number 6, Dec. 2011 PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- Jordan Journal of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering (JJMIE), Volume 2, Number 3, Sep. 2008 PDFDocument56 pagesJordan Journal of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering (JJMIE), Volume 2, Number 3, Sep. 2008 PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- 1 Blockchain S Roles in Meeting Key Supply 2018 International Journal of InfDocument10 pages1 Blockchain S Roles in Meeting Key Supply 2018 International Journal of InfHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1877705812027750 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S1877705812027750 MainsmrajbeNo ratings yet

- A Multi Criteria Approach to Designing Cellular Manufacturing SystemsDocument10 pagesA Multi Criteria Approach to Designing Cellular Manufacturing SystemsHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- A Study On Lean Manufacturing Implementa PDFDocument10 pagesA Study On Lean Manufacturing Implementa PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- A Classification of Multi-Criteria and e PDFDocument9 pagesA Classification of Multi-Criteria and e PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- A Study On Increasing Competitveness of PDFDocument23 pagesA Study On Increasing Competitveness of PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- Supplier Selction MethodsDocument8 pagesSupplier Selction MethodsPoornananda ChallaNo ratings yet

- Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) System Implementation A Case For User ParticipationDocument9 pagesEnterprise Resource Planning (ERP) System Implementation A Case For User ParticipationastariwulandariNo ratings yet

- The Benefits of Enterprise Resource Planning ERP System Implementation in Dry Food Packaging Industry - 2013 - Procedia Technology PDFDocument7 pagesThe Benefits of Enterprise Resource Planning ERP System Implementation in Dry Food Packaging Industry - 2013 - Procedia Technology PDFHadiBiesNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Correlation and Linear Regression TechniquesDocument21 pagesCorrelation and Linear Regression TechniquesDumy NeguraNo ratings yet

- ES5 Estaistica 1Document4 pagesES5 Estaistica 1Leonardo NegreteNo ratings yet

- Capm 2004 ADocument35 pagesCapm 2004 Aobaidsimon123No ratings yet

- Good News For Value StoksDocument17 pagesGood News For Value StoksMario Riveros M.No ratings yet

- Estimating Illegal Fishing From Enforcement OfficersDocument9 pagesEstimating Illegal Fishing From Enforcement Officersbbjarne.hansenNo ratings yet

- Flexible Instructional Delivery Plan (FIDP) : What To Teach?Document3 pagesFlexible Instructional Delivery Plan (FIDP) : What To Teach?Arniel LlagasNo ratings yet

- Design Work Standards and Manpower PlanningDocument46 pagesDesign Work Standards and Manpower PlanningRechelle100% (1)

- Test 4Document69 pagesTest 4Neha YadavNo ratings yet

- Chapter I - Introduction: 1.1 Background of The StudyDocument29 pagesChapter I - Introduction: 1.1 Background of The StudyNarendra bahadur chandNo ratings yet

- Does Playing Apart Really Bring Us Together - Preprint - v1Document18 pagesDoes Playing Apart Really Bring Us Together - Preprint - v1Mirian Josaro LlasaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10, CBSDocument46 pagesChapter 10, CBSHimNo ratings yet

- HR AnalyticsDocument40 pagesHR AnalyticsRicha Mukhi100% (16)

- Adaptive Control of Nonlinear Systems Parametric and Non-Parametric ApproachDocument6 pagesAdaptive Control of Nonlinear Systems Parametric and Non-Parametric ApproachSHIVAM CHAURASIANo ratings yet

- Machine Learning Algorithms ExplainedDocument15 pagesMachine Learning Algorithms ExplainedShiv Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Time Series PDFDocument34 pagesTime Series PDFkirthi nairNo ratings yet

- New Batches Info: Quality Thought Ai-Data Science DiplomaDocument16 pagesNew Batches Info: Quality Thought Ai-Data Science Diplomaniharikarllameddy.kaNo ratings yet

- Mathematical Modelling of Engineering Problems: Received: 2 October 2018 Accepted: 23 November 2018Document6 pagesMathematical Modelling of Engineering Problems: Received: 2 October 2018 Accepted: 23 November 2018David PazNo ratings yet

- Customer Loyalty Marketing Research - A Comparative Approach Between Hospitality and Business JournalsDocument12 pagesCustomer Loyalty Marketing Research - A Comparative Approach Between Hospitality and Business JournalsM Syah RezaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal TitusDocument11 pagesJurnal TitusTitusBrahamSimamoraNo ratings yet

- 5116Document21 pages5116Malcolm ChristopherNo ratings yet

- Impact of GDP and Inflation On Unemployment Rate: A Study of Pakistan Economy in 2000-2010Document18 pagesImpact of GDP and Inflation On Unemployment Rate: A Study of Pakistan Economy in 2000-2010Rohan MadiaNo ratings yet

- Engineering Degree Project: - Reducing Environmental Impact For Artificial Grass Pitches at SnowfallDocument62 pagesEngineering Degree Project: - Reducing Environmental Impact For Artificial Grass Pitches at SnowfallGabs PalabayNo ratings yet

- Module 5: Multiple Regression Analysis: Tom IlventoDocument20 pagesModule 5: Multiple Regression Analysis: Tom IlventoBantiKumarNo ratings yet

- Latent Variable Moderation: Techniques for Assessing Interactions in SEMDocument6 pagesLatent Variable Moderation: Techniques for Assessing Interactions in SEMMarium KhanNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Budaya Organisasi Terhadap KineDocument14 pagesPengaruh Budaya Organisasi Terhadap KineDidik PrasetyaNo ratings yet

- YaDocument18 pagesYaAnnisya KaruniawatiNo ratings yet

- 151 Effects of Physiotherapy Treatment On Knee Oa Gai 2009 Osteoarthritis AnDocument2 pages151 Effects of Physiotherapy Treatment On Knee Oa Gai 2009 Osteoarthritis AnEmad Tawfik AhmadNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Talent Management Strategies: Pamela Bethke-Langenegger, Philippe Mahler and Bruno StaffelbachDocument16 pagesEffectiveness of Talent Management Strategies: Pamela Bethke-Langenegger, Philippe Mahler and Bruno StaffelbachFarzana Mahamud RiniNo ratings yet

- Accident Analysis and PreventionDocument12 pagesAccident Analysis and PreventionSadegh AhmadiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 FYP1 (Example)Document24 pagesChapter 2 FYP1 (Example)Ma IlNo ratings yet