Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Role of Honey in The Management of Wounds: Discussion

Uploaded by

Ni Wayan Ana PsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Role of Honey in The Management of Wounds: Discussion

Uploaded by

Ni Wayan Ana PsCopyright:

Available Formats

DISCUSSION

The role of honey in the

management of wounds

A review of the evidence on the advantages of using honey as a topical wound

treatment together with practical recommendations for its clinical use

he widespread development of

antibiotic -resistant bacteria l

has generated an increasing

interest in the use of alternate therapies

for the treatment of infected wounds. In

1989, an editorial in the Journal of the

Royal Society of Medicine, referring to

reports o n the successful use o f

ho ney in wounds, stated: 'The

therapeutic potential of uncontaminated,

pure honey is grossly underutilized.' This

paper examines how the chemical and

physical properties of honey may facilitate

wound healing and offers guidance on

practical issues related to clinical use.

Antibacterial action

A number of laboratory studies have

demonstrated the significant antibacterial

activity of honey. Using concentrations of

honey ranging from 1.8% to 11% (v/v),

researchers have achieved complete inhibition of the major wound-infecting

species of bacteria.3 Other reports include:

complete inhibition of a collection of

strains of MRSA (1%-4% v/v honey);4

complete inhibition of 58 strains of coagulase-positive Staphylococcus aureus isolated from infected wounds (2%-4% v/v

honey);5 complete inhibition of 20 strains

of Pseudomonas isolated from infected

wounds (5.5%-8.7% v/v honey).6

The antibacterial activity of honey has

also been shown in vivo, with reports of

infected wounds dressed with honey

becoming sterile in 3-6 days,7,8 7 days9-11

and 7-10 days.12

Solutions of high osmolarity, such as

honey, sugar and sugar pastes, inhibit

microbial growth13 because the sugar

molecules 'tie up' water molecules so that

bacteria have insufficient water to support

their growth. When used as dressings,

dilution of these solutions by wound

exudate reduces osmolarity to a

P.C.Molan, BSc, PhD, Director, Honey Research

Unit, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand

Abscesses; Burns; Honey; Moist wound

healing;-Necrotising-fasclitis;

Ulcers; Wound infection

level that ceases to control infection,

especially if wounds are infected with

Staphylococcus aureus (a common osmotolerant wound pathogen). 14, 15 Even

when diluted by exudate to a point where

its osmolarity no longer inhibits bacterial

growth, honey's additional antibacterial

components still ensure sterility.

Honey's antibacterial activity is

thought to be due primarily to the

presence of hydrogen peroxide, generated

by the action of an enzyme that the

bees add to nectar.16 Some floral

sources provide additional antibacterial

components by way of plant-derived

chemicals in the nectar, such as

flavonoids and aromatic acids.17 This

partly explains the very large variation

that is seen in the antibacterial potency of

honeys from different floral sources.18

However, the variation results mainly

from differences in the amount of

hydrogen peroxide formed in the honeys,

because nectar from some floral sources

contains components that break down

hydrogen peroxide or destabilise the

enzyme that produces it. Exposure of

honey to heat and light also deactivates

the enzyme that produces hydrogen

per-oxide.18

Differences

in

the

antibacterial potency are reflected in the

varying sensitivity results reported for

wound-infecting species of bacteria.18

The use of hydrogen peroxide as an

antiseptic agent in the treatment of

wounds is generally considered to give

outcomes that are less than successful.

However, when honey is used, the

hydrogen peroxide is delivered in a very

J O U R N A L O F W O U N D C A R E S E P T E M B E R , VOL 8 , NO 8, 1999

different way. Hydrogen peroxide is an

effective antimicrobial agent if present at a

sufficiently high concentration,19 but at

'higher concentrations-it-causes-cellular

and protein damage in tissues by giving

rise to oxygen radicals 20,21 This limits the

concentration of hydrogen peroxide that

can be used as an antiseptic.

Honey effectively provides a slow-release

delivery of hydrogen peroxide; the enzyme

producing it becomes active only when

honey is diluted16 and continues to

produce it at a steady rate for at least 24

hours (unpublished work). In honey

diluted with an equal volume of pH7

buffer, the concentration of hydrogen

peroxide accumulating in one hour is typically about 1000 times less than that in

the solution of hydrogen peroxide (3%)

that is commonly used as an antiseptic.

Honey also has high levels of

antioxi-dants,22 which would protect

wound tissues from oxygen radicals that

may be produced by the hydrogen

peroxide.

Deodorising action

The deodorisation of offensive odour

from wounds is an expected conse quence of honey's antibacterial action.

The malodour is due to ammonia,

amines and sulphur compounds, which

are produced when infecting bacteria

metabolise amino acids from proteins in

the serum and necrotic tissue in a

wound. The rapidity of honey's deodorising action is probably due to the provision of a rich source of glucose, which

would be used by the infecting bacteria

in preference to amino acids,23 resulting

in the production of lactic acid instead of

malodorous compounds.

Debriding action

The debriding action of honey has not

yet been explained. It may be simply a

415

DISCUSSION

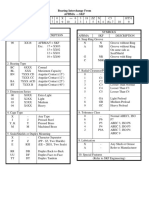

Table I. Advantages of using honey

Wound care advantages

It provides a protective barrier to

prevent cross-infection10,34,31,40,41,54,61

It creates an antibacterial moist healing

environment

It rapidly dears infecting bacteria7-12

including antibiotic-resistant strains37

It has a debriding effect and its osmotic

action causes an outflow of lymph, lifting

debris from the wound bed8-10,31,33,34,38,49,50,61

It rapidly removes malodour9-11,33,34,61

It hastens healing through stimulation of

tissue regeneration7-10,12, 26-30,33,37-41

It prevents scarring and

hypertrophicaton9,30,33,48

It minimises the need for skin

grafting8,9,30,61

It is non-adherent and therefore minimises

trauma and pain during dressing

changes30,34,37,39,48,49,55

Its and-inflammatory action reduces

oedemas.9,10,31-33

It has no adverse effect on wound

tissues10,11,31,37,40,49

Economic advantages

Reduced costs of dressing materials and

antibacterial agents12,37,52,59

More rapid healing8,11,12,26,30,37,41,53

The obviation of surgical

debridement8-10,31

The obviation of skin grafting8,9,30,33

Ease of use allows patients to manage

their own wound care at home, thus

reducing nursing costs

result of the moist healing environment

that is created by the honey dressing.

Another possibility is that it is an enzymatic debridement process. There have

been no reports of honey having any

proteolytic activity, but the debridement

action may be due to activation of

pro-teases in wound tissues by hydrogen

peroxide generated by the honey

dressing. It has been reported that

metalloproteases can be activated by

oxidation,24 and the inhibitors of serine

proteases can be deactivated by

oxidation.25

Anti-inflammatory action

Histological studies using experimental

wounds in animals have shown that

416

honey has an anti-inflammatory influence even when there is no infection present, this being seen as a reduction in the

number of inflammatory cells infiltrating

the wound tissue. 26-29 This confirms

clinical observations of reduction in

inflammation,26,30 oedema,9,10,31-33 and

exudation,9,10,26 and a soothing effect26,34,35

when honey is applied to wounds. This

anti-inflammatory influence may be associated with the antioxidant content of

honey, which has been found to be of a

significant level when assayed as the

capacity of honey to scavenge free radicals?, Oxygen radicals are involved in various aspects of inflammation,25 and the

application of antioxidants to burns has

been shown to reduce inflammation.36

Stimulation of tissue growth

Honey promotes the formation of clean

healthy granulation tissue7-10,12,30,32,37-39

and

epithelialisation,9,10,30,33,40

as

demonstrated histologically in animal

studies 26-29,41 This may be due to the

generation of hydrogen peroxide, low

levels of which stimulate angiogenesis42

and the growth of fibroblasts43 Increased

angiogenesis would provide more oxygen,

which is a limiting factor for tissue

regeneration.

Acidification of the wound may also be

responsible: honey typically has a pH from

3 to 4, and topical acidification has been

shown to promote healing44 by causing

more oxygen to be released from haemoglobin.45 Also it has been suggested that the

decreased turgor resulting from the

application of honey may increase tissue

oxygenation;10

the

reduction

in

hydrostatic pressure in the interstitial

fluid resulting from anti-inflammatory

action would allow improved circulation

in the tissues.

Another theory is that the nutrient content of honey may stimulate growth it

has a wide range of amino acids, vitamins

and trace elements, in addition to large

quantities of readily assimilable sugars.

Studies in animals46 and humans47 have

shown an association between topical

application of nutrients to wounds and

increased growth of granulation tissue.

In addition, the high osmolarity of

honey will draw fluid out from a wound

bed. This outflow of lymph with its dissolved nutrients would also provide

nutrition for regenerating tissue.

Clinical experience

Honey has been used to treat a number

of different wound types, including surgical wounds8,11,12,41,48-51 most notably

v u l v e c to m y

wo u nd s , 8 , 1 1 , 1 2 , 4 1 , 4 8 - 5 1

w o u n d s related to trauma,10,50,52-54

wounds associated with necrotising

fasciitis,9,33 pressure tlICerS10.38.53'55.58 and

venous and diabetic leg ulcers.52,59,60

However, it is in the management of

burn wounds that the role of honey has

probably received most attention.

Investigations have shown honey to

be

more

effective

than

other

products29.30.34,61 in the management of

partial-thickness burns. A retrospective

study also has shown that honey is as

effective as silver sulphadiazine in the

management of burns.62

In prospective randomised controlled

trials comparing honey with silver sulphadiazine-impregnated gauze in the treatment of fresh partial-thickness burns,

honey was shown to produce an early subsidence of acute inflammatory changes

and quicker wound healing, better control

of infection, better relief of pain, less irritation of the wound, less exudation, and a

lower incidence of hypertrophic scar and

post-burn contracture.30,61 The advantages

of using honey in the management of

wounds are listed in Table 1.

Guidelines for practice

Honey varies in consistency, from liquid

to solid, with the glucose content crystallised. Solid honeys may be liquified by

warming and semi-solid honeys can often

be liquified by stirring. Heating above

37C should be avoided, as this may bum

the patient and will destroy the enzyme

that produces hydrogen peroxide.

The honey should be spread evenly on

the dressing pad rather than directly to the

wound. The amount of honey required on

a wound depends on the amount of

exudation; the beneficial effects of honey

on wound tissues will be reduced or lost

if small quantities of honey become

diluted by large amounts of exudate.

Wounds with deep infection require

greater amounts of honey to obtain an

effective level of antibacterial activity by

diffusion into the wound tissues.

Dressing technique

Typically, 30mL of honey is used on a

10cm x 10cm dressing. Dressing pads

impregnated with honey (such as those

produced by REG International, New

Zealand) (Figs 1 & 2) are the most convenient way of applying honey to surface

wounds. Occlusive or absorbent secondary

dressings are needed to prevent honey

oozing out from the wound dressing (Fig

3). The frequency of dressing changes will

also depend on how rapidly the honey is

diluted by exudate. Daily dressing changes

are usual, but up to three times daily may

JOURNAL OF WOUND CARE SEPTEMBER, VOL 8, NO 8, 1999

uniquely high level of a herbal antibacterial

63

component that is particularly effective

against

some

of

the

important

3

wound-infecting bacteria. However, ail

honeys vary very much in their potency.

There is a high chance of the activity being

little better than that of sugar if a honey is

63

taken at random. There is a large variance in

the level of antibacterial activity even within

honeys from the same floral source.

be necessary.

Exudation should be

reduced by the anti-inflammatory action of

honey, so the frequency of dressing

changes should decline as treatment

progresses. Deep wounds (Figs 4-6) or

abscesses are most easily filled by using

honey packed in 'squeeze-out' tubes, now

available commercially (Actimel) (Fig 7).

Honey quality

Although ancient physicians were aware that

honeys from particular sources had the

best therapeutic properties, little regard is

given to this in current clinical practice. Any

honey to be used for infected wounds

should therefore have its antibacterial

activity assayed. A 'UMF' rating (equivalent to

the concentration of phenol which has the

same activity against Staphylococcus aureus)

is being used by producers of manuka

honey to show the potency of its

plant-derived component.

Potential risk

There is no report of any type of infection

Honeys from Leptospermum species (for

resulting from the application of honey to

example,

manuka

honey)CARE

can SEPTEMBER,

have a VOL 8, NOwounds

JOURNAL

OF WOUND

8, 1999 although there is no reference in

reports of the clinical application of honey on

open wounds being sterilised before use.

Honey sometimes contains spores of

clostridia, which poses a small risk of infection,

such as wound botulism. Any risk can be

overcome by the use of honey that has been

treated by gamma-irradiation, which kills

clostridial spores without loss of any of the

honey's antibacterial activity."

Conclusion

This paper has described the chemical and

physical properties of honey and has

shown how these may have a positive

influence on wound healing. Honey is an ideal

substance to use as a wound dressing

material. Its fluidity, especially when

warmed, allows it to be spread and makes

honey dressings easy to apply and

37,39,55

remove.

The osmotic action resulting

from honey's high sugar content draws out

wound fluid and thus dilutes the honey that is

in contact with the wound bed, minimising

adhesion or damage to the granulating surface

30-44,49

of the wounc1

when the dressing is

34

removed. The high solubility of honey in

water allows residual

417

DISCUSSION

'

honey to be washed away by bathing54

Although the clinical experiences

detailed in this paper show positive results,

more quality randomised controlled trials

are needed to provide evidence to

encourage the use of honey in wound care.

REFERENCES

I. Greenwood, D. Sixty years on: antimicrobial drug

resistance comes of age. Lancet 1995; 346: (Suppl I), s I,

2. Zumla, A., Lulat, A. Honey; a remedy rediscovered. J R

Soc Med 1989; 82: 384-385,

3. Willix, D.J., Molan, P.C., Harfoot, C.J. A comparison of

the sensitivity of wound-infecting species of bacteria to the

antibacterial activity of manuka honey and other honey.]

Appl Bacteriol 1992: 73: 388-394.

4. Molan, P.. Brett. M. Honey has potential as a dressing

for wounds infected with MRSA. The Second Australian

Wound Management Association Conference: 1998

March 18-21; Brisbane, Australia.

5. Cooper, R.A., Molan, P.C., Harding, K.G. The

effectiveness of the antibacterial activity of honey against

strains of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from infected

wounds.) R Soc Med 1999; 1999; 92: 283-285.

6. Cooper, RA, Molan, P.C. The use of honey as an

antiseptic in managing Pseudomonas infection.) Wound

Care 1999; 8: 4, 161-164.

7. Branikl, F.J. Surgery in Western Kenya. Ann R Con Surg

Eng! 1981; 63: 348-352.

8. Cavanagh, D., Beazley, J., Ostapowica F. Radical

operation for carcinoma of the vulva: a new approach to

wound healing.) Obstet Gynaecol Commonw 1970; 77:

I 1, 1037.1140.

9, Efem, S.E.E. Recent advances in the management of

Fournier's gangrene; preliminary observations. Surgery

1993; 113: 2. 200-204,

10. Efem S.E,E, Clinical observations on the wound healing

properties of honey. Sr) Surg 1988; 75: 679.681.

11. Phuapradit, W., Saropala, N. Topical application of

honey In treatment of abdominal wound disruption. Austr

NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 1992; 32: 4, 381-384.

12. Armors, P.J. The use of honey in the treatment of

infected wounds. Trop Doct 1980; 10: 91.

13. Chirife, J., Scarmato, G., Herszage, L. Scientific basis for

use of granulated sugar in treatment of Infected wounds.

Lancet 1982; I: (March 6), 560-561.

14. Chirife, J., Herszage, L. Joseph, A. et at In vitro study of

bacterial growth inhibition in concentrated sugar solutions:

microbiological basis for the use of sugar in treating

infected wounds. Antimicrobial Agents & Chemother 1983;

23: 5, 766-773.

I 5. Herszage, L, Montenegro, J.R., Joseph, A.L

Tratamiento de las heridas supur-adas con azcecar

granulado comercial. Bol Trab Soc Argent Or 1980; 41:

21-22, 315-330.

16. White, J.W., Subers, M.H., Schepartz, A.I. The

identification of inhibine, the antibacterial factor in honey,

as hydrogen peroxide and Its origin In a honey

glucose-oxidase system. Blochim alophys Acta 1963; 73:

57-70.

17. Molan P.C. The antibacterial activity of honey, I: The

nature of the antibacterial activity. Bee World 1992; 73: 1,

5-28.

18. Molan, P.C. The antibacterial activity of honey. 2:

Variation in the potency of the antibacterial activity. Bee

World 1992; 73: 2, 59-76.

19. Roth, L.A., Kwan, S., Sporns, P. Use of a disc-assay

system to detect oxytetracycline residues in honey.

J Food Prot 1986; 49: 6, 436-441.

20. Cochrane, C.G. Cellular injury by oxidants. Am J Med

1991; 91: (Suppl 3c), 235.305.

21. Simon, R.H., Scoggin, C.H.. Patterson, D. Hydrogen

peroxide causes the fatal injury to human fibroblasts

exposed to oxygen radicals. J Biol Chem 1981; 256: 14,

7181-7186.

22. Frankel, 5., Robinson, G.E., Berenbaum, M.R.

Antioxidant capacity and correlated characteristics of 14

unifioral honeys. J Apic Res 1998; 37: I, 27-31.

23. Nychas, G.J., Dillon, V.M., Board, R.G. Glucose, the key

substrate in the microbiological changes in meat and certain

meat products. Brotechnol App/ Biochem 1988; 10: 203-231.

24. Van Wart, H.E.. Birkedal-Hansen, H. The cystein

418

int J Crude Drug Res 1988; 26: 3, 161-168.

KEY ISSUES FOR PRACTICE

The use of honey dressings may have a

beneficial effect in wound management

and can be cost-effective

Solid honeys may be liquified by stirring or

warming but honey should not be heated

above 37C

The honey should be spread evenly and

applied to the dressing pad rather than

directly the wound

Deep wounds can be filled with honey from

a 'squeeze-out' tube

The amount of honey required depends on

the amount of exudate; wounds with deep

infection require greater amounts of

honey

Dressing pads pre-impregnated with honey

are the most convenient method of applying

honey to wounds

Frequency of dressing change depends on

quantity of exudate

switch: a principle of regulation of metalloproteinase

activity with potential applicability to the entire matrix

metalloproteinase gene family. Proc Nat Acad Sri USA

1990;87: 14.5578-5582,

25.

Floh, L. Beckmann, R., Giertz, H. et al.

Oxygen-centred free radicals as mediators of

inflammation. In: Sies, H. (ed). Oxidative Stress. London,

Orlando: Academic Press, 1985.

26.

Burlando, F. Sull'azione terapeutica del miele

nelle ustioni. Minerva Dermatol 1978; 113: 699-706.

27.

Gupta, S.K., Singh, H., Varshney, A.G. et

al. Therapeutic efficacy of honey in infected wounds in

buffaloes. Indian J Anim Sri 1992; 62: 6, 521-523. 28,

Kumar, A., Sharma, V.K., Singh, H.P. et al. Efficacy of some

indigenous drugs in tissue repair in buffaloes. Indian Vet)

1993; 70: I, 42-44.

29. Postures, T.J., Bosch, M.M.C., Dutrieux, R. et al.

Speeding up the healing of burns with honey. An

experimental study with histological assessment of

wound biopsies. In: Mizrahl, A., tensity, Y. (eds). Bee

Products: Properties, applications and apitherapy. New York,

NY: Plenum Press, 1997.

30. Subrahmanyam, M. A prospective randomised clinical

and histological study of superficial burn wound healing

with honey and silver sulfadiazine. Bums 1998; 24: 2,

157-161.

31. Subrahmanyam, M. Honey dressing versus boiled

potato peel in the treatment of burns: a prospective

randomized study. Bums 1996; 22: 6, 491-493.

32. Dumrongiert, E. A follow-up study of chronic wound

healing dressing with pure natural honey. ) Nat Res Counc

Than 1983; 15: 2, 39-66.

33. Hejase,11.J., Simonin,

BIhrle, R., Coogan. C.L

Genital Fournier's gangrene: experience with 38 patients.

Urology 1996; 47: 5. 734-739.

34. Subrahmanyam, M. Honey impregnated gauze versus

polyurethane film (OpSite) in the treatment of burns: a

prospective randomised study. Br) Piast Surg 1993; 46: 4,

322.323.

35. Keast-Butler J. Honey for necrotic malignant breast

ulcers. Lancet 1980;

(October II ), 809.

36. Tanaka, H., Hanumadass, M., Matsuda. H. et al.

Hemodynamic effects of delayed initiation of antioxidant

therapy (beginning two hours after burn) in extensive

third-degree burns.] Burn Care Rehabil 1995; 16: 6,

610-615.

37. Farouk, A., Hassan, T., Kashif, H. et at Studies on

Sudanese bee honey: laboratory and clinical evaluation.

38. Hutton. D.J. Treatment of pressure sores. Nurs Times

1966; 62: 46, 1533-1534.

Wadi. M., Al-Amin, H., Farouq, A. et al. Sudanese bee

honey in ;he treatment of suppurating wounds. Arab

Medico 1987; 3: 16-18.

39. Subrahmanyam, M. Honey-impregnated gauze versus

amniotic membrane in the treatment of burns. Bums

1994; 20:4, 331-333.

40. Bergman, A., Yana!, J., Weiss, J. et al. Acceleration of

wound healing by topical application of honey: an animal

model. Am J Surg 1983; 145: 374-376.

41. Tur, E., Bolton, L, Constantine, B.E. Topical

hydrogen peroxide treatment of ischemic ulcers in the

guinea pig: blood recruitment in multiple skin sites. J Am

Acad Dermatoi 1995; 33:2 (Part I), 217-221.

42. Schmidt, R.J., Chung, LY., Andrews, A.M. et al.

Hydrogen peroxide is a murine (L929) fibroblast cell

proliferant at micro- to nanomolar concentrations. In:

Harding, K.G., Cherry. G., Dealey, C.. Turner, T.D.

(eds). Proceedings of the 2nd European Conference on

Advances in Wound Management. London: Macmillan

Magazines, 1993.

43. Kaufman, T., Eichenlaub, E.H., Angel, M.F. et al.

Topical acidification promotes healing of experimental

deep partial thickness skin burns; a randomised

double-blind preliminary study. Bums 1985; 12:

84-90.

44. Leveen, N.H., Falk, G., Borek, B. et al. Chemical

acidification of wounds: an adjuvant to healing and the

unfavourable action of alkalinity and ammonia, Ann Surg

1973; 178: 6, 745-753.

45. Kaufman, T., Levin, M., Hurwitz, D.J. The effect of

topical hyperalimentadon on wound healing rate and

granulation tissue formation of experimental deep

second-degree burns in guinea-pigs. Bums 1984; 10: 4,

252-256.

46. Viljanto, J., Raekallio, J. Local hyperallmentation of

open wounds. Br) Surg 1976; 63: 3, 427-430.

47. McInerney, R.J.F. Honey: a remedy rediscovered.

J R Soc Med 1990; 83: 127.

48. Bulman, M.W. Honey as a surgical dressing. Middlesex

Hosp./ 1955; 55: 188-189.

49. Ndaylsaba, G., Bazira, L, Habonimana, E. et at

Clinical and bacteriological results in wounds treated

with honey. J Orthop Surg 1993; 7: 2, 202-204.

50. Dany-Mazeau, M., Pautard, G. L'utilisadon du miel

dans le processus de cicatrisation: de la ruche a PhOpital.

Krankenpfl Soins Infirm 1991; 84: 3, 63-69.

52: Wood, B., Rademaker, M., Molan, P.C. Manuka

honey, a low cost leg ulcer dressing. N Z Med J 1997;

110: 107.

53. Hamdy, M.H., El-Banby, MA, Khakifa ICI. et al. The

antimicrobial effect of honey in the management of

septic wounds. In: Proceedings of the Fourth International

Conference on Apiculture in Tropical Climates. London:

International Bee Research Association, 1989.

54. Green, AE Wound healing properties of honey. Br J

Surg 1988; 75: 12, 1278.

55. Blomfleld, R. Honey for decubitus ulcers. J Am Med

Assoc 1973; 224: 6, 905.

56. Dany-Mazeau, M.P.G. Honig auf die Wunde.

Krankenpflege 1992; 46: 1, 6-10.

57. SomeHield, S.D. Honey and healing.) R Soc Med

1991; 84: 3, 179.

58. Weheida, S.M.. Nagubib, H.H. El-Banna, H.M. et at

Comparing the effects of two dressing techniques on

healing of low grade pressure ulcers. J Med Res Inst

Alexandria Univ 1991; 12: 2.259-278.

59. Harris, S. Honey for the treatment of superficial

wounds: a case report and review. Primary intention 1994;

2:4, 18-23.

60. Tovey, F.I. Honey and healing. j R Sot Med 1991: 84:

7, 447.

61. Subrahmanyam, M. Topical application of honey in

treatment of burns. Br .1 Surg 1991; 78: 4, 497-498.

62. Adesunkanmi, K., Oyelami, 0.A. The pattern and

outcome of burn injuries at Wesley Guild Hospital,

Ilesha, Nigeria: a review of 156 cases.) Trop Med Hyg

1994; 97: 2, 108-112.

63. Allen, K.L, Molan, P.C., Reid, G.M. A survey of the

antibacterial activity of some New Zealand honeys. J

Phorm Pharmacol 1991; 43: 12, 817-822.

64. Molan, P.C., Allen, K.L The effect of

gamma-irradiation on the antibacterial activity of honey.

J Phorm Pharmacol 1996; 48: 1206-1209.

JOURNAL OF WOUND CARE SEPTEMBER, VOL 8, NO 8, 1999

You might also like

- Honey: A Biologic Wound DressingDocument22 pagesHoney: A Biologic Wound DressingTeuku FennyNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Properties of Natural Honey: A Review of LiteratureDocument7 pagesAntimicrobial Properties of Natural Honey: A Review of LiteratureDanielle PecsonNo ratings yet

- Research Article: International Research Journal of PharmacyDocument5 pagesResearch Article: International Research Journal of PharmacyGrassellaNo ratings yet

- Honey Paper - Rose CooperDocument3 pagesHoney Paper - Rose CooperMax Jordan DooleyNo ratings yet

- Manisha Deb Mandal Shyamapada Mandal: Honey: Its Medicinal Property and Antibacterial ActivityDocument9 pagesManisha Deb Mandal Shyamapada Mandal: Honey: Its Medicinal Property and Antibacterial Activityriyaldi_dwipaNo ratings yet

- 276) 2010 Cerio - Mechanism Action Clinical Benefits Colloidal Oatmeal Dermatologic PracticeDocument5 pages276) 2010 Cerio - Mechanism Action Clinical Benefits Colloidal Oatmeal Dermatologic Practicezebulon78No ratings yet

- Throughout History Man Has Had To Contend With Dermal WoundsDocument9 pagesThroughout History Man Has Had To Contend With Dermal Woundswisnutato22No ratings yet

- 9 Honey Medicine ReviewDocument20 pages9 Honey Medicine ReviewjivasumanaNo ratings yet

- Application of Essential Oils As Natural Cosmetic PreservativesDocument15 pagesApplication of Essential Oils As Natural Cosmetic PreservativesjosareforNo ratings yet

- Elhage 2021Document8 pagesElhage 2021Trần Duy TânNo ratings yet

- JURNAL INTERNASIONAL SENSITIVITAS (Study Antibacterial Activity of Honey Against Some Common Species Of)Document9 pagesJURNAL INTERNASIONAL SENSITIVITAS (Study Antibacterial Activity of Honey Against Some Common Species Of)windaNo ratings yet

- Molecules 20 16068Document17 pagesMolecules 20 16068RezanovianingrumNo ratings yet

- Invitro Evaluation of Antibacterial Activity of Honey Against Wound PathogenDocument5 pagesInvitro Evaluation of Antibacterial Activity of Honey Against Wound PathogenEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Effectiveness of Honey-Based Alginate Hydrogel On Wound Healing in Rat ModelDocument5 pagesEvaluation of Effectiveness of Honey-Based Alginate Hydrogel On Wound Healing in Rat ModelAlief AkbarNo ratings yet

- 7762075-Dreger and WielgusDocument15 pages7762075-Dreger and WielgusAlma KunicNo ratings yet

- Actividad EnzimaticDocument11 pagesActividad EnzimaticherfuentesNo ratings yet

- Effect of Natural Honey (Produced by African Sculata in Guyana)Document5 pagesEffect of Natural Honey (Produced by African Sculata in Guyana)Melivea Paez HerediaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Honey Dressing On Chronic UlcerDocument6 pagesImpact of Honey Dressing On Chronic UlcerIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Journal Homepage: - : Manuscript HistoryDocument6 pagesJournal Homepage: - : Manuscript HistoryIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- !! 1-S2.0-S2666154322001934-MainDocument9 pages!! 1-S2.0-S2666154322001934-Mainancuta.lupaescuNo ratings yet

- Hydroalcoholic Extract Based-Ointment From Punica Granatum L. Peels With Enhanced in Vivo Healing Potential On Dermal WoundsDocument9 pagesHydroalcoholic Extract Based-Ointment From Punica Granatum L. Peels With Enhanced in Vivo Healing Potential On Dermal WoundsLa Ode Muhammad FitrawanNo ratings yet

- Krim Mentimum11Document15 pagesKrim Mentimum11Takeshi MondaNo ratings yet

- Hipochlorous Acid Anjing Kucing 2-5 Mikro L LDocument10 pagesHipochlorous Acid Anjing Kucing 2-5 Mikro L LyulianaNo ratings yet

- Determination of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Agaricus Bisporus From Romanian MarketsDocument7 pagesDetermination of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Agaricus Bisporus From Romanian MarketsKhairul WaldiNo ratings yet

- Scientific Brochure: Science For Healthy SkinDocument25 pagesScientific Brochure: Science For Healthy SkinHunt ApplegateNo ratings yet

- Al Waili2003Document6 pagesAl Waili2003wizuraihakimroyNo ratings yet

- Research Life ScienceDocument8 pagesResearch Life ScienceDan Jenniel CedeñoNo ratings yet

- Ijbms 16 731Document12 pagesIjbms 16 731TututWidyaNurAnggrainiNo ratings yet

- Antibacterial Profile of Honey On Staphylococcus Aureus Isolated From Surgical Wound in Awomamma General HospitalDocument5 pagesAntibacterial Profile of Honey On Staphylococcus Aureus Isolated From Surgical Wound in Awomamma General HospitalasclepiuspdfsNo ratings yet

- Body Malodours and Their Topical Treatment AgentsDocument14 pagesBody Malodours and Their Topical Treatment AgentsChiper Zaharia DanielaNo ratings yet

- 58 Arshad AJBIODocument12 pages58 Arshad AJBIOvidiNo ratings yet

- Antibacterial Activity of Phyto Essential Oils On Flaccherie Causing Bacteria in The Mulberry Silk Worm, B.Mori. LDocument5 pagesAntibacterial Activity of Phyto Essential Oils On Flaccherie Causing Bacteria in The Mulberry Silk Worm, B.Mori. LIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Mod Med La v6n1p22 enDocument7 pagesMod Med La v6n1p22 enta22122001No ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Activity of HoneyDocument20 pagesAntimicrobial Activity of HoneyYadiNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic, Pestisida HoneyDocument9 pagesAntibiotic, Pestisida HoneyDian Laras SuminarNo ratings yet

- SavlonDocument4 pagesSavlonArif MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Sabinsa Developing All Natural Personal Care Products 2009 v3Document12 pagesSabinsa Developing All Natural Personal Care Products 2009 v3JeanNo ratings yet

- Gelee RoyaleDocument5 pagesGelee Royalerabahhalim183No ratings yet

- Apiteraphy HandbookDocument69 pagesApiteraphy HandbookladygagajustinNo ratings yet

- Title Defense Life Group 10Document8 pagesTitle Defense Life Group 10Dan Jenniel CedeñoNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Effect of Honey Produced by On Some Common Human PathogensDocument6 pagesAntimicrobial Effect of Honey Produced by On Some Common Human Pathogensreal_septiady_madrid3532No ratings yet

- Artikel JurnalDocument5 pagesArtikel Jurnalsalman fardNo ratings yet

- Allantoin Anti Inflamatory ActivityDocument17 pagesAllantoin Anti Inflamatory ActivityValentina CarreroNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Activity of Plant Extracts ThesisDocument4 pagesAntimicrobial Activity of Plant Extracts Thesiskimberlybundypittsburgh100% (1)

- Antimicrobial Property of Over-the-Counter Essential Oils and Ayurvedic Powders Against Aeromonas Hydrophila Isolated From Labeo RohitoDocument4 pagesAntimicrobial Property of Over-the-Counter Essential Oils and Ayurvedic Powders Against Aeromonas Hydrophila Isolated From Labeo RohitoInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- Antibiotic, Pesticide, and Microbial Contaminants of Honey Human HealthDocument10 pagesAntibiotic, Pesticide, and Microbial Contaminants of Honey Human HealthJuan Alejandro JiménezNo ratings yet

- An Invitro Study of Determination of Anti-Bacterial, Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Piper Betel Essential OilDocument8 pagesAn Invitro Study of Determination of Anti-Bacterial, Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Piper Betel Essential OilSaiful AbdulNo ratings yet

- Exploring Cucumber Extract For Skin RejuvenationDocument12 pagesExploring Cucumber Extract For Skin Rejuvenationemiliana.wirawanNo ratings yet

- Preliminary PagesDocument43 pagesPreliminary PagesShem AngelesNo ratings yet

- Surface Culturing of Chromobacterium Violaceum MTCC 2656 For Violacein Production and Prospecting Its Bio ActivitiesDocument12 pagesSurface Culturing of Chromobacterium Violaceum MTCC 2656 For Violacein Production and Prospecting Its Bio Activitieskrishna YurekaNo ratings yet

- The Antibacterial Effect of Roselle Hibiscus SabdaDocument4 pagesThe Antibacterial Effect of Roselle Hibiscus SabdaIid Fitria TNo ratings yet

- Assyifa Jurnal, Minawati Said SuatDocument11 pagesAssyifa Jurnal, Minawati Said SuatNur WahidaNo ratings yet

- Colloidal Oatmeal Formulations and The Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis - JDDonline - Journal of Drugs in DermatologyDocument1 pageColloidal Oatmeal Formulations and The Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis - JDDonline - Journal of Drugs in DermatologyMelvy RozaNo ratings yet

- IJCRT2402204Document11 pagesIJCRT2402204VickyNo ratings yet

- Biological Properties and Therapeutic Activities of Honey in Wound Healing: A Narrative Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument21 pagesBiological Properties and Therapeutic Activities of Honey in Wound Healing: A Narrative Review and Meta-AnalysisJuan Enrique EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Pylori: Susceptibility The Antibacterial Activity HoneyDocument4 pagesPylori: Susceptibility The Antibacterial Activity HoneyLoredanaNo ratings yet

- Handbook ApitherapyDocument60 pagesHandbook ApitherapyengrezgarNo ratings yet

- Example Review of Related StudiesDocument5 pagesExample Review of Related StudiesMarianne MontefalcoNo ratings yet

- 27 Vol9Document6 pages27 Vol9Amine BenineNo ratings yet

- Ibnt 06 I 3 P 377Document2 pagesIbnt 06 I 3 P 377Ni Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0002937814008084Document8 pagesPi Is 0002937814008084snrarasatiNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument5 pagesContent ServerNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument4 pagesContent ServerNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- ObsosDocument6 pagesObsosNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Quinn Et A Predictores de Composicion de Leche 2012Document8 pagesQuinn Et A Predictores de Composicion de Leche 2012Adriana CavazosNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument3 pagesContent ServerNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument4 pagesContent ServerNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Cervical Stitch (Cerclage) For Preventing Pregnancy Loss: Individual Patient Data Meta-AnalysisDocument17 pagesCervical Stitch (Cerclage) For Preventing Pregnancy Loss: Individual Patient Data Meta-AnalysisNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- The Causes of CancerDocument11 pagesThe Causes of CancerShailNo ratings yet

- Cerebrovascular Accident in B-Thalassemia Major (B-TM) and B-Thalassemia Intermedia (b-TI)Document3 pagesCerebrovascular Accident in B-Thalassemia Major (B-TM) and B-Thalassemia Intermedia (b-TI)Ni Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- 2Document10 pages2Ni Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- The Hypercoagulable State in Thalassemia: Hemostasis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology Clinical Trials and ObservationsDocument9 pagesThe Hypercoagulable State in Thalassemia: Hemostasis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology Clinical Trials and ObservationsNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- 1391283400Document7 pages1391283400Ni Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- 07 DJMCJ v7 I1 151 Nazia Akhter Obstructed LabourDocument4 pages07 DJMCJ v7 I1 151 Nazia Akhter Obstructed LabourDewi Rahmawati SyamNo ratings yet

- P ('t':'3', 'I':'668636885') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Document10 pagesP ('t':'3', 'I':'668636885') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Ni Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Clinical Characteristics of Clear Cell Carcinoma of The OvaryDocument6 pagesClinical Characteristics of Clear Cell Carcinoma of The OvaryNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Title of The Presentation: Your SubtitleDocument2 pagesTitle of The Presentation: Your SubtitleNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Chemotherapy For Recurrent and Metastatic Cervical CancerDocument5 pagesChemotherapy For Recurrent and Metastatic Cervical CancerNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Do Clear Cell Ovarian Carcinomas Have Poorer Prognosis Compared To Other Epithelial Cell Types? A Study of 1411 Clear Cell Ovarian CancersDocument7 pagesDo Clear Cell Ovarian Carcinomas Have Poorer Prognosis Compared To Other Epithelial Cell Types? A Study of 1411 Clear Cell Ovarian CancersNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Using Antimicrobial Surgihoney To Prevent Caesarean Wound InfectionDocument5 pagesUsing Antimicrobial Surgihoney To Prevent Caesarean Wound InfectionNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Distosia Ncbi (Ana)Document8 pagesDistosia Ncbi (Ana)Ni Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- 416 1391 1 PBDocument5 pages416 1391 1 PBNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Passage and Passanger Image Collection (Ana)Document16 pagesPassage and Passanger Image Collection (Ana)Ni Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Skrining CMVDocument10 pagesSkrining CMVNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Jurnal GastroenterohepatologiDocument18 pagesJurnal GastroenterohepatologiRarasRachmandiarNo ratings yet

- Cytokeratin 7 and Cytokeratin 19 Expressions in Oval Cells and Mature Cholangiocytes As Diagnostic and Prognostic Factors of CholestasisDocument6 pagesCytokeratin 7 and Cytokeratin 19 Expressions in Oval Cells and Mature Cholangiocytes As Diagnostic and Prognostic Factors of CholestasisNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Liver Disease Pediatric PatientDocument14 pagesLiver Disease Pediatric PatientNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- CMV Primer Non PrimerDocument3 pagesCMV Primer Non PrimerNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- EXAMPLE 8.6 Veneer Grades and RepairsDocument2 pagesEXAMPLE 8.6 Veneer Grades and RepairsnickNo ratings yet

- Multi Organ Dysfunction SyndromeDocument40 pagesMulti Organ Dysfunction SyndromeDr. Jayesh PatidarNo ratings yet

- FBC MNCS Service-, Error-, Infocodes ENDocument23 pagesFBC MNCS Service-, Error-, Infocodes ENDragos Stoian100% (1)

- MSDS DowthermDocument4 pagesMSDS DowthermfebriantabbyNo ratings yet

- Tips For A Healthy PregnancyDocument2 pagesTips For A Healthy PregnancyLizaNo ratings yet

- CCNA Training New CCNA - RSTPDocument7 pagesCCNA Training New CCNA - RSTPokotete evidenceNo ratings yet

- Wildlife Emergency and Critical CareDocument14 pagesWildlife Emergency and Critical CareRayssa PereiraNo ratings yet

- 1.1.3.12 Lab - Diagram A Real-World ProcessDocument3 pages1.1.3.12 Lab - Diagram A Real-World ProcessHalima AqraaNo ratings yet

- Precision CatalogDocument256 pagesPrecision CatalogImad AghilaNo ratings yet

- Practice For Mounting Buses & Joints-374561Document11 pagesPractice For Mounting Buses & Joints-374561a_sengar1No ratings yet

- The Working of KarmaDocument74 pagesThe Working of KarmaSuhas KulhalliNo ratings yet

- Ecological Quality RatioDocument24 pagesEcological Quality RatiofoocheehungNo ratings yet

- Statics: Vector Mechanics For EngineersDocument39 pagesStatics: Vector Mechanics For EngineersVijay KumarNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument3 pagesDaftar PustakaMel DaNo ratings yet

- Adaptive Reuse Architecture Documentation and Analysis 2168 9717 1000172Document9 pagesAdaptive Reuse Architecture Documentation and Analysis 2168 9717 1000172Komal HundiaNo ratings yet

- Flusser-The FactoryDocument2 pagesFlusser-The FactoryAlberto SerranoNo ratings yet

- Asco Series 238 ASCO Pilot Operated Solenoid Valves (Floating Diaphragm)Document2 pagesAsco Series 238 ASCO Pilot Operated Solenoid Valves (Floating Diaphragm)Khyle Laurenz DuroNo ratings yet

- Joby Aviation - Analyst Day PresentationDocument100 pagesJoby Aviation - Analyst Day PresentationIan TanNo ratings yet

- Rectifier 5G High Density Embedded Power (3U Power Rack, Three Phase Four Wire) E...Document4 pagesRectifier 5G High Density Embedded Power (3U Power Rack, Three Phase Four Wire) E...Lintas LtiNo ratings yet

- GSD Puppy Training Essentials PDFDocument2 pagesGSD Puppy Training Essentials PDFseja saulNo ratings yet

- Rachel Joyce - A Snow Garden and Other Stories PDFDocument118 pagesRachel Joyce - A Snow Garden and Other Stories PDFИгорь ЯковлевNo ratings yet

- Kimi No Na Wa LibropdfDocument150 pagesKimi No Na Wa LibropdfSarangapani BorahNo ratings yet

- Nomenclatura SKFDocument1 pageNomenclatura SKFJuan José MeroNo ratings yet

- Adriano Costa Sampaio: Electrical EngineerDocument3 pagesAdriano Costa Sampaio: Electrical EngineeradrianorexNo ratings yet

- GBJ0232 - en GLX 3101 T2Document43 pagesGBJ0232 - en GLX 3101 T2mnbvqwert100% (2)

- Arts Class: Lesson 01Document24 pagesArts Class: Lesson 01Lianne BryNo ratings yet

- Medical GeneticsDocument4 pagesMedical GeneticsCpopNo ratings yet

- Gujral FCMDocument102 pagesGujral FCMcandiddreamsNo ratings yet

- Isulat Lamang Ang Titik NG Tamang Sagot Sa Inyong Papel. (Ilagay Ang Pangalan, Section atDocument1 pageIsulat Lamang Ang Titik NG Tamang Sagot Sa Inyong Papel. (Ilagay Ang Pangalan, Section atMysterious StudentNo ratings yet

- LinkageDocument9 pagesLinkageHarshu JunghareNo ratings yet