Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Evidence

Uploaded by

RZ ZamoraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Evidence

Uploaded by

RZ ZamoraCopyright:

Available Formats

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

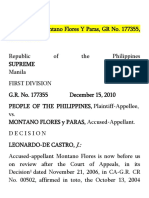

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

EN BANC

A.M. No. P-08-2450

June 10, 2009

(Formerly OCA IPI No. 00-27-CA-P)

AURORA B. GO, Complainant,

vs.

MARGARITO A. COSTELO, JR., SHERIFF IV, REGIONAL TRIAL COURT,

BRANCH 11, CALUBIAN, LEYTE,Respondent.

DECISION

Per Curiam:

Before this Court is the affidavit-complaint1 dated June 19, 2003 filed by

complainant Aurora B. Go with the Office of the Court Administrator

(OCA), charging respondent Margarito A. Costelo, Jr., Sheriff IV of the

Regional Trial Court (RTC), Branch 11, Calubian, Leyte, with grave

misconduct, falsification and abuse of authority.

In her complaint, Go alleged that she executed a Deed of Absolute Sale in

favor of her sister Anita Conde over a parcel of land covered by Tax

Declaration No. ARP 09004-00109. On November 8, 2001, while the

complainant was in Taiwan, she received a call from Conde, who

informed her that respondent Sheriff was going to subject said parcel of

land to an auction sale on that same day, pursuant to a Writ of

Execution2 dated July 18, 2001 issued against complainant by the

Page 1 of 99

Municipal Trial Court in Cities (MTCC) of Cebu City in an ejectment

case.3Complainant advised Conde to avail herself of legal remedies such

as filing a third-party claim to prevent the auction, but despite proof of

ownership shown by Conde to respondent, the latter proceeded with the

sale.

Complainant further alleged that respondent Sheriff: (1) took advantage

of her absence from the Philippines and surreptitiously and hastily

proceeded with the auctioning of the real property; (2) persisted in

conducting the auction sale with patent partiality in favor of Doris

Sunbanon, the prevailing party in the ejectment case; (3) made it appear

that a person residing in the subject property received the notice of

auction by falsifying the signature of the alleged person in the

purportedly received copy of the notice, but such person was unknown

to complainant and Conde; (4) failed to make proper posting of the

notice of auction; (5) did not acknowledge the documents evidencing the

transfer of ownership of property from complainant to Conde, and said

that the Deed of Absolute Sale was "gawa-gawa" [simulated]; and (6)

falsified the entries in the Certificate of Sale by stating that it was

executed and notarized on November 8, 2001 by a certain Atty. Roberto

dela Pea when in truth a certified photocopy of the notarial book of

Atty. Dela Pea shows that no such document was notarized on said date

or immediately thereafter.

Also, complainant stated that it was doubtful whether respondent

actually conducted an auction sale on November 8, 2001, considering

that a strong typhoon hit Calubian from November 6 to 8, 2001, as a

result of which offices were closed. She further averred that, on the day

of the auction sale, Conde went to the Sheriffs Office, where she was told

by respondent that there would be no auction sale that day. Conde was

advised to bring the Deed of Sale and third-party claim to respondents

house, so that he could make a report to the MTCC, Branch 2, Cebu City

that Conde was the new owner of the property. When Conde brought the

required documents to respondents house, she learned that respondent

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

still failed to report to the court her claim over the property. This

prompted Conde to file a Third-Party Claim4 on November 15, 2001

before the MTCC, Branch 2, Cebu City. However, when Conde went to

respondents office to deliver a photocopy of her third-party claim,

respondent showed her the Certificate of Sale5 in the name of Doris

Sunbanon, who was the highest bidder in the auction sale held on

November 8, 2001.

On the other hand, respondent filed his Comment6 dated September 9,

2003, wherein he denied that he committed irregularities in auctioning

the subject property, for a Levy on Execution had been made based on

the certified true copy of the tax declaration issued by the Municipal

Assessor of Calubian, Leyte and the same was duly annotated by the

Register of Deeds for the Province of Leyte. He claimed that, before

November 12, 2001, he had no knowledge that the property sold at

public auction was owned by a certain Anita Conde, and that the sole

basis of the Levy on Execution and the Sheriffs auction sale was the

mere fact that the declared owner of the property was complainant Go,

the losing party in the ejectment case. It was only when Conde filed her

third-party claim that respondent came to know that there was a thirdparty claimant over the property in question.

Respondent also denied having described the Deed of Absolute Sale as

"gawa-gawa." He averred that before he conducted the auction sale, he

sent a copy of the Notice of Sale on Execution of Real Property to the

complainant by registered mail, but it was returned with a notation

"party moved out" and marked "RTS" by the Calubian Post Office. He,

likewise, claimed that the auction sale had not been cancelled or

postponed due to inclement weather, and that he had the Certificate of

Sale duly notarized on November 8, 2001.

Respondent pointed out that the complainant executed the Deed of

Absolute Sale in favor of Conde on January 24, 2001, barely two months

after the Court of Appeals promulgated its decision in the ejectment case

Page 2 of 99

dated November 16, 2000 against complainant, which showed that the

complainant transferred her property to prevent the court from levying

the same.

On June 29, 2004, the OCA recommended that the complaint be referred

to Judge Alejandro Diongzon of the RTC of Calubian, Leyte on the ground

that the issues raised by the complainant could not be resolved on the

basis of the submitted pleadings and documents alone, and that a fullblown investigation was necessary,7 a recommendation that the Court

adopted in its Resolution8 dated October 20, 2004. However, on January

19, 2005, complainant filed with the OCA an Urgent Motion for

Inhibition9 of Judge Diongzon claiming that the latter would be partial in

handling the case, because said judge was the approving officer of the

Certificate of Sale. In a Resolution10 dated April 20, 2005, the Court

recalled its Resolution dated October 20, 2004 and, instead, directed

Judge Crisostomo Garrido of the RTC of Carigara, Leyte to conduct an

investigation and submit a report and recommendation thereon within

sixty (60) days from receipt of the Resolution.

On May 17, 2006, respondent filed before the Court a Motion11 praying

that the investigation of the case be returned to the RTC, Branch 11,

Calubian, Leyte on the ground that Judge Diongzon had already retired.

His motion was denied in a Memorandum12 of the OCA dated September

18, 2006.

In his Report and Recommendation13 dated February 20, 2007, Judge

Garrido found respondent to have acted without authority in conducting

a public auction sale of the subject property on execution, stating that:

Nowhere could be gleaned from the said order that Respondent Sheriff,

Costelo, Jr. was authorized to conduct public auction sale of the property

on execution. Neither was there any evidence presented that the Sheriff

of MTCC, Branch 2, Cebu City has delegated such authority to Sheriff

Costelo, Jr., to conduct a public auction sale of the property on execution.

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

The Respondent Sheriff could have exercised prudence and restraint in

the performance of his duty. Instead of conducting [a] public auction sale

of the property on execution, he could have filed his return of the

property levied, to the MTCC, Branch 2, Cebu City for its sheriff to

conduct the public auction sale, pursuant to the provision of the 2nd

paragraph of Sec. [6] Rule 39, 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure. Blinded by

the expectation of sheriffs fees, the respondent sheriff had forgotten his

bounden duties and responsibilities as employee of the judiciary that

public office is a public trust.

The Certificate of Sale, Minutes of Auction Sale dated November 8, 2001,

are fictitious, fabricated and spurious documents, mere concoction of

facts to give a semblance of legality to the illegal acts of Sheriff Costelo,

Jr. This evaluation finds support from the Certification issued by the

Cebu PAGASA and the Philippine Coast Guard, Cebu Station, Cebu City,

viz:

CERTIFICATION Cebu PAGASA

On November 6, 7 & 8, 2001, Storm Signal No. 2, with heavy rains of

gusty winds of 54 to 65 kilometers per hour were raised over the entire

provinces of Cebu, Samar, Leyte, Dinagat Island, Bohol, Masbate and

Panay Island, with rough to very rough seas, with wave height of 3 to 5

meters.14

CERTIFICATION Philippine Coast Guard

On these three days that the typhoon battered these islands in the

Visayas, no vessels of 2000 gross tonnage and less were given clearance

to leave Cebu for Leyte, Samar and other Visayan islands.15

Evidence admissible when original document is a public record. When

the original of a document is in the custody of a public officer or is

Page 3 of 99

recorded in a public office, its contents may be proved by a certified copy

issued by the public officer in custody thereof. (emphasis theirs)

Obviously, it was impossible for the judgment creditor Doris Sunbanon

to be present in Leyte on November 6, 7 & 8, 2001, moreso, in Calubian,

Leyte attending a public auction sale on November 8, 2001 at the Office

of the Regional Trial Court, Branch 11, Calubian, Leyte, when all water

and air transportation facilities in Cebu were not given any clearance to

leave for Leyte and the other Visayan islands. Experience had taught us

that when PAGASA raises typhoon signal No. 2 over the provinces

affected, school classes and offices, both public and private, are

automatically suspended.

Judgment Creditor Doris U. Sunbanon was not presented in Court during

the hearing of this case, to corroborate the allegation of Respondent

Sheriff that she was present during the auction sale of the real property

on execution on November 8, 2001 in Calubian, Leyte, nor in the days

prior thereto. There was no evidence presented that indeed, Doris U.

Sunbanon was in Leyte on the aforesaid dates. Not even hotel bills,

receipts of her stay in Leyte or marine vessel or airplane tickets were

presented for her return trip to Cebu City from Leyte, after the

November 8, 2001 alleged auction sale, indicia of her absence in the

public auction sale of the real property on execution on November 8,

2001.

Neither any of the Court personnel of RTC Branch 11, Calubian, Leyte,

who were allegedly present and had signed the logbook on November 8,

2001 was presented in Court, to corroborate the testimony of Sheriff

Costelo, Jr., that indeed, they were holding office on November 8, 2001,

despite typhoon signal no. 2 in the provinces of Samar and Leyte,

indicative that the logbook allegedly signed by [the] Court employees is

spurious and of doubtful authenticity, unavailing and undeserving credit

for it can be easily accomplished to serve ones ulterior motive.

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

The validity, genuineness, authenticity and due execution of the

Certificate of Sale issued by Respondent Sheriff Costelo, Jr., dated

November 8, 2001, was put in issue when Notary Public Roberto Dela

Pea of Calubian, Leyte, who allegedly notarized the Certificate of Sale

on November 8, 2001 was put to the witness stand. Roberto Dela Pea

denied that he notarized the alluded Certificate of Sale and that his

signature appearing on the acknowledgment portion of the said

document is fake, a product of falsification and forgery. The entries

denominated as Document 161, Page 37, Book 3, Series of 2000,

appearing on the Certificate of Sale were forged, falsified and fictitious

entries.

Document No. 161, Page No. 37, Book 3, Series of 2000 as entered in the

Notarial Register of Notary Public Roberto Dela Pea refers to a

document denominated as Cancellation and Discharge of Mortgage,

executed by and between Spouses Fileo and Angeles Arias, and Baruel

Rimandaman, Leonila B. Pepito and Alfredo Lagora, and not the

Certificate of Sale issued by the respondent sheriff.

Courts observation and examination of the said entries on page 37 of

the Notarial Register of Roberto Dela Pea, appears to be genuine and

authentic, without any erasure or alteration, written in freehand writing

and in chronological order of events, written in the middle portion of

page 37 of the notarial registry, indicative that the document entered

thereto is the true act of the notary public in recording his transaction

for the day, pursuant to his oath of office.

There is credence to the testimony of Roberto Dela Pea that the

Certificate of Sale issued by the respondent sheriff, was fictitious,

falsified and a product of forgery. Moreover, Roberto Dela Pea, being 70

years old and in the twilight of his life, testified clearly and in a

straightforward manner, relative to the entries on page 37 of his Notarial

Register. Other infirmities in the other pages in his Notarial Register

could only be attributed to old age.

Page 4 of 99

Sheriff Margarito Costelo, Jr. having acted without [any] authority to

conduct a public auction sale of the real property on execution, the

public auction sale is illegal, invalid and void ab initio. Under the rules,

supra, the public auction sale of the real property on execution shall only

be conducted at the office of the Clerk of Court, MTCC, Branch 2, Cebu

City, the Court which issued the Writ of Execution.

Judiciary officers must, at all times, be accountable to the people. They

serve with utmost degree of integrity, responsibility, loyalty and

efficiency in their duties. In the case at bar, respondent sheriff, Margarito

Costelo, Jr. has [been] remiss of his duties and must account to the

people who repose their trust on him. Such grave misconduct committed

by the respondent sheriff, deserves the highest degree of sanctions. The

respondent sheriff is a disgrace to the Judiciary.

WHEREFORE, premises considered, it is most respectfully

recommended:

1. That the public auction sale of real property on execution be

declared Null and Void;

2. That respondent MARGARITO COSTELO, JR., be dismissed

from the service for Grave Misconduct, Dishonesty and unfit of a

judicial officer (sic), with forfeiture of all benefits, except leave

credits, if any, with prejudice for re-employment in the

government or any agency and instrumentality thereof, including

government-owned and controlled corporations.

RESPECTFULLY RECOMMENDED.16

On March 22, 2007, respondent filed with the RTC of Carigara, Leyte, a

Motion for Reconsideration17 of the Report and Recommendation of

Judge Garrido; and on June 1, 2007, an Omnibus Supplemental Motion

for Reconsideration/Motion to Re-Open the Case and to Inhibit the

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

Investigating Judge.18 He claimed that the penalty of dismissal from

service was too harsh, considering the circumstances of the case, and

submitted the following to support his motion: (1) affidavit19 of Roberto

dela Pea recanting his earlier affidavit and testimony that his signature

in the Certificate of Sale was falsified; (2) Daily Time Records20 of the

court employees of the RTC, Branch 11, Calubian, Leyte, showing perfect

attendance and no late days for the month of November 2001, except for

Utility Worker Elpidio Gudmalin, who filed a leave of absence from

November 13 to 15, 2001; (3) photocopy of the Order21 dated November

8, 2001 of the Investigating Judge during the hearing in Sp. Proc. No. 714,

to prove that the Investigating Judge himself conducted a hearing on

November 8, 2001; and (4) PNP Leyte Crime Laboratory Report dated

June 7, 2007, stating that the signature of Roberto dela Pea appearing

on the duplicate copy of the Sheriffs Certificate of Sale and his signature

duly submitted belonged to one and the same person.

In a Resolution dated August 6, 2007, the Court referred Judge Garridos

Report and Recommendation dated February 20, 2007 to the OCA for

evaluation, report and recommendation within 30 days from notice. On

March 12, 2008, the OCA submitted a Memorandum stating that:

We find no reason to disturb the findings of Judge Crisostomo Garrido.

During the course of the investigation, the Investigating Judge saw the

demeanor of the witnesses and he personally knows the conditions

prevailing in the area during the time that there was allegedly a typhoon.

Respondent had the opportunity to present transcripts of court hearing,

if any, on November 8, 2001. The belated submission of the joint

affidavit of his co-employees after learning that he would be dismissed

from the service can be taken as a mere act of saving respondent from

the recommended penalty of dismissal.

We are inclined to believe that the Daily Time Records submitted [for]

the month of November 2001 did not reflect the true attendance of court

employees. It would seem improbable that in a coastal town like

Page 5 of 99

Calubian, all the employees would register a perfect attendance with no

late despite hoisting of Storm Signal No. 2 in the province for 3 days. As

convincingly observed by the Investigating Judge, not one among the

court personnel who were allegedly present on November 8, 2001

testified during the investigation "indicative that the logbook signed by

the court employees is spurious and of doubtful authenticity x x x."

As to the affidavit of Notary Public Roberto Dela Pea recanting his

earlier testimony, the same hardly deserves credence. The Court has

invariably regarded affidavits of recantation as highly unreliable. As held

in People vs. Rojo (114 SCRA 304), an affidavit of retraction which

indicates it [to] be a mere afterthought has no probative value.

As to the PN[P] Crime Laboratory Report yielding a same signature

result, it must be noted that Roberto Dela Pea gave a specimen of his

signature only on 31 May 2007, after he has executed his affidavit

recanting his earlier testimony.

The rest of the alleged newly discovered evidence are obtainable at the

time the investigation was conducted. For an evidence to be considered

"newly discovered," it could not have been discovered prior to the trial

by the exercise of due diligence.

In view of the foregoing, it is respectfully recommended that the instant

case be redocketed as a regular administrative case and that, as

submitted by the Investigating Judge, respondent Sheriff Margarito A.

Costelo, Jr. be DISMISSED FROM THE SERVICE effective immediately

with forfeiture of all benefits except his accrued leave credits with

prejudice to reemployment in any branch or instrumentality of the

government, including government-owned or controlled corporations.

The Court agrees with the recommendation of the OCA affirming the

findings of Judge Garrido.

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

In his Report, the Investigating Judge confirmed that respondent effected

a valid service of the Notice of Sale on the judgment debtor, herein

6,22

complainant, in accordance with Section

Rule 13 of the Rules of Civil

Procedure. The Notice of Sale on Execution of Real Property was

likewise duly published for three (3) consecutive weeks by the Sunday

Punch, a newspaper of regional circulation in Leyte and Samar, from

October 15 to 21, 22 to 28 and October 29 to November 4, 2001, as

evidenced by the Affidavit of Publication23 executed by its publisher,

Danilo Silvestrece.

However, respondent had no authority to conduct the public auction sale

of the property in question. Neither was there any evidence to show that

the Sheriff of the MTCC, Branch 2, Cebu City, delegated such authority to

respondent. The Order dated September 25, 2001 of Presiding Judge

Anatalio S. Necesario of the MTCC, Branch 2, Cebu City, clearly provided

that the power and authority given to respondent was only to levy on the

property, as quoted:

ORDER

Acting on the Amended Motion filed by plaintiff-movant for being welltaken and meritorious, the same is hereby granted.

The deficiency judgment in the amount of P143,294.39 is supported by

the sheriffs return of the Writ of Execution already attached to the

expediente of the case.

WHEREFORE, the Deputy Sheriff of this Court (Court) or the Deputy

Sheriff of the Regional Trial Court of Calubian, Leyte is hereby

authorized to levy on the property of the defendants situated in

Calubian, Leyte for the full satisfaction of the deficiency judgment up to

the extent of the sum of P143,294.39 exclusive of costs.

Page 6 of 99

SO ORDERED.24

Even assuming that respondent was given the authority to hold an

auction sale, the complainant was able to establish during the

investigation that the former did not actually conduct a public auction

sale of the property on execution, in violation of paragraphs (c) and (d)

of Section 15, Rule 39 of the Rules of Civil Procedure, quoted as follows:

Sec. 15. Notice of Sale of Property on Execution. Before the sale of

property on execution, notice thereof must be given as follows:

xxxx

(c) In case of real property, by posting for twenty (20) days in

the three (3) public places abovementioned, a similar notice

particularly describing the property and stating where the

property is to be sold, and if the assessed value of the property

exceeds fifty thousand (P50,000.00) pesos, by publishing a copy

of the notice once a week for two (2) consecutive weeks in one

newspaper selected by raffle, whether in English, Filipino, or any

major regional language published, edited and circulated or, in

the absence thereof, having general circulation in the province or

city;

(d) In all cases, written notice of the sale shall be given to the

judgment obligor, at least three (3) days before the sale, except

as provided in paragraph (a) hereof where notice shall be given

at any time before the sale, in the same manner as personal

service of pleadings and other papers as provided by section 6 of

Rule 13.

The notice shall specify the place, date and exact time of the sale which

should not be earlier than nine oclock in the morning and not later than

two oclock in the afternoon. The place of the sale may be agreed upon

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

by the parties. In the absence of such agreement, the sale of real

property or personal property not capable of manual delivery shall be

held in the office of the clerk of court of the Regional Trial Court or the

Municipal Trial Court which issued the writ or which was designated by

the appellate court. In the case of personal property capable of manual

delivery, the sale shall be held in the place where the property is

located.25

The fact that a public auction sale could not have possibly taken place on

November 8, 2001 is corroborated by the Certifications of Cebu PAGASA

and the Philippine Coast Guard that there was a typhoon on the date of

sale. Moreover, no evidence was presented in court to prove that

Sunbanon was at the auction sale. Neither did any of the court personnel

of the RTC, Branch 11, Calubian, Leyte, testify that they held office during

the storm on November 8, 2001.

Respondents belated submission of evidence, which was done only after

the investigation had been completed, does not merit probative value, as

the same was a mere afterthought. It has been consistently held that an

affidavit of recantation is unreliable and deserves scant consideration,

since the asserted motives for the repudiation are commonly held

suspect, and the veracity of the statements made in the affidavit of

repudiation are frequently and deservedly subject to serious

doubt.26 Moreover, the OCA observed that the Daily Time Record

appeared to be altered or falsified, as it was shown that there was no

work on November 8, 2001 due to the inclement weather, but

respondent was indicated as purportedly present.

In Malabanan v. Metrillo,27 the Court defined misconduct as a

transgression of some established and definite rule of action, a forbidden

act, a dereliction of duty, unlawful behavior; willful in character,

improper or wrong behavior, while "gross" has been defined as "out of

all measure beyond allowance; flagrant; shameful; such conduct as is not

to be excused." As a sheriff and officer charged with the dispensation of

Page 7 of 99

justice, respondents conduct and behavior must be circumscribed with

the heavy burden of responsibility.28 In the present case, by the very

nature of their functions, sheriffs, like respondent, are called upon to

discharge their duties with care and utmost diligence and, above all, to

be above suspicion. Instead of following what the MTCC directed in its

Order, respondent conducted a public auction sale when in fact he had

no authority to do so and even falsified a Certificate of Sale. Having been

in the service for 17 years, respondent should have taken the rules by

heart, for it is expected that someone as considerably experienced as he

is would know the proper procedure for disposing of property at a

public auction sale.

Notably, while the Investigating Judge concluded that the Certificate of

Sale and Minutes of Auction Sale were fictitious, fabricated and spurious

documents, he found respondent liable for gross misconduct and

dishonesty without mentioning his findings as to respondents acts of

falsification and abuse of public authority. In the Courts assessment of

the records, however, it finds that respondent was likewise liable for

falsification of an official document when he falsified the Certificate of

Sale and Minutes of Public Auction Sale, and abuse of public authority

when he disposed of the property by auction sale instead of levying the

same, as he was directed to do in the Order of the MTCC judge.1aVVphi1

Respondents acts are clearly in violation of Canon IV of the Code of

Conduct for Court Personnel,29 the pertinent provisions of which state:

Sec. 1. Court personnel shall at all times perform official duties

properly and with diligence, and to commit themselves

exclusively to the business and responsibilities of their office

during working hours.

Sec. 3. Court personnel shall not alter, falsify, destroy or mutilate

any record within their control. This provision does not prohibit

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

amendment, correction or expungement of records or

documents pursuant to a court order.

Sec. 6. Court personnel shall expeditiously enforce rules and

implement orders of the court within the limits of their

authority.

The Uniform Rules on Administrative Cases in the Civil

Service30 likewise provides that grave misconduct is punishable by

dismissal from the service under Section 52-A(3), Rule IV thereof, while

falsification of official document is also punishable by dismissal from the

service under Section 52-A(6) thereof.

In Padua v. Paz,31 the Court found respondent sheriff liable for grave

misconduct and falsification of public document and, accordingly,

dismissed him from the service when the latter committed perjury and

gave false testimony. In the present case, respondents act of conducting

a public auction sale, which amounted to grave misconduct, and his

falsification of the Certificate of Sale and the Minutes of Auction Sale are

in flagrant disregard of the law and deserve the supreme penalty of

dismissal.

The Court has consistently held that sheriffs play a significant role in the

administration of justice, for they are primarily responsible for the

execution of a final judgment, which is "the fruit and end of the suit, and

is the life of the law." Thus, sheriffs are expected to show a high degree

of professionalism in performing their duties. As officers of the court,

they are expected to uphold the norm of public accountability and to

avoid any kind of behavior that would diminish or even just tend to

diminish the faith of the people in the Judiciary.32 Herein respondent

failed to abide by these postulates.

Let this case serve as a warning to all court personnel that the Court, in

the exercise of its administrative supervision over all courts and their

Page 8 of 99

personnel, will not hesitate to enforce the full extent of the law in

disciplining and purging from the Judiciary all those who are not

befitting the integrity and dignity of the institution, even if such

enforcement would lead to the maximum penalty of dismissal from the

service despite their length of service.

WHEREFORE, respondent Sheriff Margarito A. Costelo, Jr. is found

GUILTY of grave misconduct, grave abuse of authority, and falsification

of official document; and is DISMISSED from the service with forfeiture

of all benefits and privileges, except accrued leave credits, if any, and

with prejudice to re-employment in any branch or agency of the

government, including government-owned or controlled corporations.

This Decision shall take effect immediately.

SO ORDERED.

REYNATO S. PUNO

Chief Justice

LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING

Associate Justice

CONSUELO YNARESSANTIAGO

Associate Justice

ANTONIO T. CARPIO

Associate Justice

RENATO C. CORONA

Associate Justice

On official leave

CONCHITA CARPIO

MORALES*

Associate Justice

MINITA V. CHICO NAZARIO

Associate Justice

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

PRESBITERO J. VELASCO, JR.

Associate Justice

TERESITA J. LEONARDO-DE

CASTRO

Associate Justice

DIOSDADO M. PERALTA

Associate Justice

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

ANTONIO EDUARDO B.

NACHURA

Associate Justice

ARTURO D. BRION

Associate Justice

LUCAS P. BERSAMIN

Associate Justice

Id. at 71-83.

10

Id. at 80.

11

Id. at 156-158.

12

Rollo, Vol. II, pp. 31-32.

13

Rollo, Vol. I, pp. 228-241.

14

Id. at 43-44.

15

Id. at 46.

16

Id. at 238-241.

17

Id. at 242-245.

18

Rollo (Vol. II), pp. 35-46.

19

Id. at 58.

20

Id. at 48-52.

21

Id. at 55.

Footnotes

*

On official leave.

Rollo, Vol. I, pp. 8-13.

Id. at 187-189.

Docketed as Civil Case No. R-36953, entitled "Doris Sunbanon v.

Aurora Go."

3

Rollo, Vol. I, p. 15.

Id. at 16.

Id. at 26-28.

Id. at 46-49.

Id. at 50.

Page 9 of 99

Sec. 6. Personal service. Service of the papers may be made

by delivering personally a copy of the party or his counsel, or by

leaving it in his office with his clerk or with a person having

charge thereof, if no person is found in his office, or his office is

not known, or he has no office, then by leaving the copy, between

the hours of eight in the morning and six in the evening, at the

partys or counsels residence, if known, with a person of

sufficient age and discretion then residing therein.

22

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

23

Rollo, Vol. I, p. 35

24

Id. at 237-238.

25

Emphasis supplied.

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

Firaza v. People of the Philippines, G.R. No. 154721, March 22,

2007, 518 SCRA 681, 692-693.

26

27

A.M. No. P-04-1875, February 6, 2008, 544 SCRA 1, 7.

Vilar v. Angel, A.M. P-06-2276, February 5, 2007, 514 SCRA

147, 153, citing Civil Service Commission v. Cortez, 430 SCRA

593 (2004).

28

29

A.M. No. 03-06-13-SC effective June 1, 2004.

Promulgated by the Civil Service Commission through

Resolution No. 99-1936 dated August 31, 1999 and implemented

by Memorandum Circular No. 19, series of 1999.

30

31

A.M. No. P-00-1445, April 30, 2003, 402 SCRA 21.

Flores v. Marquez, A.M. P-06-2277, December 6, 2006, 510

SCRA 35, 44.

32

Page 10 of 99

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

SECOND DIVISION

G.R. No. 172671

April 16, 2009

MARISSA R. UNCHUAN, Petitioner,

vs.

ANTONIO J.P. LOZADA, ANITA LOZADA and THE REGISTER OF

DEEDS OF CEBU CITY, Respondents.

DECISION

QUISUMBING, J.:

For review are the Decision1 dated February 23, 2006 and

Resolution2 dated April 12, 2006 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. CV.

No. 73829. The appellate court had affirmed with modification the

Order3 of the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Cebu City, Branch 10

reinstating its Decision4 dated June 9, 1997.

The facts of the case are as follows:

Sisters Anita Lozada Slaughter and Peregrina Lozada Saribay were the

registered co-owners of Lot Nos. 898-A-3 and 898-A-4 covered by

Transfer Certificates of Title (TCT) Nos. 532585 and 532576 in Cebu City.

The sisters, who were based in the United States, sold the lots to their

nephew Antonio J.P. Lozada (Antonio) under a Deed of Sale7 dated March

11, 1994. Armed with a Special Power of Attorney8 from Anita, Peregrina

went to the house of their brother, Dr. Antonio Lozada (Dr. Lozada),

located at 4356 Faculty Avenue, Long Beach California.9 Dr. Lozada

Page 11 of 99

agreed to advance the purchase price of US$367,000 or P10,000,000 for

Antonio, his nephew. The Deed of Sale was later notarized and

authenticated at the Philippine Consuls Office. Dr. Lozada then

forwarded the deed, special power of attorney, and owners copies of the

titles to Antonio in the Philippines. Upon receipt of said documents, the

latter recorded the sale with the Register of Deeds of Cebu. Accordingly,

TCT Nos. 12832210 and 12832311 were issued in the name of Antonio

Lozada.

Pending registration of the deed, petitioner Marissa R. Unchuan caused

the annotation of an adverse claim on the lots. Marissa claimed that

Anita donated an undivided share in the lots to her under an

unregistered Deed of Donation12 dated February 4, 1987.

Antonio and Anita brought a case against Marissa for quieting of title

with application for preliminary injunction and restraining order.

Marissa for her part, filed an action to declare the Deed of Sale void and

to cancel TCT Nos. 128322 and 128323. On motion, the cases were

consolidated and tried jointly.

At the trial, respondents presented a notarized and duly authenticated

sworn statement, and a videotape where Anita denied having donated

land in favor of Marissa. Dr. Lozada testified that he agreed to advance

payment for Antonio in preparation for their plan to form a corporation.

The lots are to be eventually infused in the capitalization of Damasa

Corporation, where he and Antonio are to have 40% and 60% stake,

respectively. Meanwhile, Lourdes G. Vicencio, a witness for respondents

confirmed that she had been renting the ground floor of Anitas house

since 1983, and tendering rentals to Antonio.

For her part, Marissa testified that she accompanied Anita to the office of

Atty. Cresencio Tomakin for the signing of the Deed of Donation. She

allegedly kept it in a safety deposit box but continued to funnel monthly

rentals to Peregrinas account.

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

A witness for petitioner, one Dr. Cecilia Fuentes, testified on Peregrinas

medical records. According to her interpretation of said records, it was

physically impossible for Peregrina to have signed the Deed of Sale on

March 11, 1994, when she was reported to be suffering from edema.

Peregrina died on April 4, 1994.

In a Decision dated June 9, 1997, RTC Judge Leonardo B. Caares

disposed of the consolidated cases as follows:

WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered in Civil Case No. CEB-16145,

to wit:

1. Plaintiff Antonio J.P. Lozada is declared the absolute owner of

the properties in question;

2. The Deed of Donation (Exh. "9") is declared null and void, and

Defendant Marissa R. Unchuan is directed to surrender the

original thereof to the Court for cancellation;

3. The Register of Deeds of Cebu City is ordered to cancel the

annotations of the Affidavit of Adverse Claim of defendant

Marissa R. Unchuan on TCT Nos. 53257 and 53258 and on such

all other certificates of title issued in lieu of the aforementioned

certificates of title;

4. Defendant Marissa R. Unchuan is ordered to pay Antonio J.P.

Lozada and Anita Lozada Slaughter the sum of P100,000.00 as

moral damages; exemplary damages of P50,000.00; P50,000.00

for litigation expenses and attorneys fees of P50,000.00; and

5. The counterclaims of defendant Marissa R. Unchuan [are]

DISMISSED.

In Civil Case No. CEB-16159, the complaint is hereby DISMISSED.

Page 12 of 99

In both cases, Marissa R. Unchuan is ordered to pay the costs of suit.

SO ORDERED.13

On motion for reconsideration by petitioner, the RTC of Cebu City,

Branch 10, with Hon. Jesus S. dela Pea as Acting Judge, issued an

Order14 dated April 5, 1999. Said order declared the Deed of Sale void,

ordered the cancellation of the new TCTs in Antonios name, and

directed Antonio to pay Marissa P200,000 as moral damages, P100,000

as exemplary damages, P100,000 attorneys fees and P50,000 for

expenses of litigation. The trial court also declared the Deed of Donation

in favor of Marissa valid. The RTC gave credence to the medical records

of Peregrina.

Respondents moved for reconsideration. On July 6, 2000, now with Hon.

Soliver C. Peras, as Presiding Judge, the RTC of Cebu City, Branch 10,

reinstated the Decision dated June 9, 1997, but with the modification

that the award of damages, litigation expenses and attorneys fees were

disallowed.

Petitioner appealed to the Court of Appeals. On February 23, 2006 the

appellate court affirmed with modification the July 6, 2000 Order of the

RTC. It, however, restored the award of P50,000 attorneys fees

and P50,000 litigation expenses to respondents.

Thus, the instant petition which raises the following issues:

I.

WHETHER THE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED AND VIOLATED

PETITIONERS RIGHT TO DUE PROCESS WHEN IT FAILED TO RESOLVE

PETITIONERS THIRD ASSIGNED ERROR.

II.

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

WHETHER THE HONORABLE SUPREME COURT MAY AND SHOULD

REVIEW THE CONFLICTING FACTUAL FINDINGS OF THE HONORABLE

REGIONAL TRIAL COURT IN ITS OWN DECISION AND RESOLUTIONS ON

THE MOTIONS FOR RECONSIDERATION, AND THAT OF THE

HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS.

III.

WHETHER THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN HOLDING

THAT PETITIONERS CASE IS BARRED BY LACHES.

IV.

WHETHER THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN HOLDING

THAT THE DEED OF DONATION EXECUTED IN FAVOR OF PETITIONER

IS VOID.

V.

WHETHER THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN NOT

HOLDING THAT ANITA LOZADAS VIDEOTAPED STATEMENT IS

HEARSAY.15

Simply stated, the issues in this appeal are: (1) Whether the Court of

Appeals erred in upholding the Decision of the RTC which declared

Antonio J.P. Lozada the absolute owner of the questioned properties; (2)

Whether the Court of Appeals violated petitioners right to due process;

and (3) Whether petitioners case is barred by laches.

Petitioner contends that the appellate court violated her right to due

process when it did not rule on the validity of the sale between the

sisters Lozada and their nephew, Antonio. Marissa finds it anomalous

that Dr. Lozada, an American citizen, had paid the lots for Antonio. Thus,

she accuses the latter of being a mere dummy of the former. Petitioner

Page 13 of 99

begs the Court to review the conflicting factual findings of the trial and

appellate courts on Peregrinas medical condition on March 11, 1994

and Dr. Lozadas financial capacity to advance payment for Antonio.

Likewise, petitioner assails the ruling of the Court of Appeals which

nullified the donation in her favor and declared her case barred by

laches. Petitioner finally challenges the admissibility of the videotaped

statement of Anita who was not presented as a witness.

On their part, respondents pray for the dismissal of the petition for

petitioners failure to furnish the Register of Deeds of Cebu City with a

copy thereof in violation of Sections 316 and 4,17 Rule 45 of the Rules. In

addition, they aver that Peregrinas unauthenticated medical records

were merely falsified to make it appear that she was confined in the

hospital on the day of the sale. Further, respondents question the

credibility of Dr. Fuentes who was neither presented in court as an

expert witness18 nor professionally involved in Peregrinas medical care.

Further, respondents impugn the validity of the Deed of Donation in

favor of Marissa. They assert that the Court of Appeals did not violate

petitioners right to due process inasmuch as it resolved collectively all

the factual and legal issues on the validity of the sale.

Faithful adherence to Section 14,19 Article VIII of the 1987 Constitution is

indisputably a paramount component of due process and fair play. The

parties to a litigation should be informed of how it was decided, with an

explanation of the factual and legal reasons that led to the conclusions of

the court.20

In the assailed Decision, the Court of Appeals reiterates the rule that a

notarized and authenticated deed of sale enjoys the presumption of

regularity, and is admissible without further proof of due execution. On

the basis thereof, it declared Antonio a buyer in good faith and for value,

despite petitioners contention that the sale violates public policy. While

it is a part of the right of appellant to urge that the decision should

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

directly meet the issues presented for resolution,21 mere failure by the

appellate court to specify in its decision all contentious issues raised by

the appellant and the reasons for refusing to believe appellants

contentions is not sufficient to hold the appellate courts decision

contrary to the requirements of the law22 and the Constitution.23 So long

as the decision of the Court of Appeals contains the necessary findings of

facts to warrant its conclusions, we cannot declare said court in error if

it withheld "any specific findings of fact with respect to the evidence for

the defense."24 We will abide by the legal presumption that official duty

has been regularly performed,25 and all matters within an issue in a case

were laid down before the court and were passed upon by it.26

In this case, we find nothing to show that the sale between the sisters

Lozada and their nephew Antonio violated the public policy prohibiting

aliens from owning lands in the Philippines. Even as Dr. Lozada

advanced the money for the payment of Antonios share, at no point

were the lots registered in Dr. Lozadas name. Nor was it contemplated

that the lots be under his control for they are actually to be included as

capital of Damasa Corporation. According to their agreement, Antonio

and Dr. Lozada are to hold 60% and 40% of the shares in said

corporation, respectively. Under Republic Act No. 7042,27 particularly

Section 3,28 a corporation organized under the laws of the Philippines of

which at least 60% of the capital stock outstanding and entitled to vote

is owned and held by citizens of the Philippines, is considered a

Philippine National. As such, the corporation may acquire disposable

lands in the Philippines. Neither did petitioner present proof to belie

Antonios capacity to pay for the lots subjects of this case.

Petitioner, likewise, calls on the Court to ascertain Peregrinas physical

ability to execute the Deed of Sale on March 11, 1994. This essentially

necessitates a calibration of facts, which is not the function of this

Court.29Nevertheless, we have sifted through the Decisions of the RTC

and the Court of Appeals but found no reason to overturn their factual

findings. Both the trial court and appellate court noted the lack of

Page 14 of 99

substantial evidence to establish total impossibility for Peregrina to

execute the Deed of Sale.

In support of its contentions, petitioner submits a copy of Peregrinas

medical records to show that she was confined at the Martin Luther

Hospital from February 27, 1994 until she died on April 4, 1994.

However, a Certification30 from Randy E. Rice, Manager for the Health

Information Management of the hospital undermines the authenticity of

said medical records. In the certification, Rice denied having certified or

having mailed copies of Peregrinas medical records to the Philippines.

As a rule, a document to be admissible in evidence, should be previously

authenticated, that is, its due execution or genuineness should be first

shown.31 Accordingly, the unauthenticated medical records were

excluded from the evidence. Even assuming that Peregrina was confined

in the cited hospital, the Deed of Sale was executed on March 11, 1994, a

month before Peregrina reportedly succumbed to Hepato Renal Failure

caused by Septicemia due to Myflodysplastic Syndrome.32 Nothing in the

records appears to show that Peregrina was so incapacitated as to

prevent her from executing the Deed of Sale. Quite the contrary, the

records reveal that close to the date of the sale, specifically on March 9,

1994, Peregrina was even able to issue checks33 to pay for her attorneys

professional fees and her own hospital bills. At no point in the course of

the trial did petitioner dispute this revelation.

Now, as to the validity of the donation, the provision of Article 749 of the

Civil Code is in point:

art. 749. In order that the donation of an immovable may be valid, it

must be made in a public document, specifying therein the property

donated and the value of the charges which the donee must satisfy.

The acceptance may be made in the same deed of donation or in a

separate public document, but it shall not take effect unless it is done

during the lifetime of the donor.

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

If the acceptance is made in a separate instrument, the donor shall be

notified thereof in an authentic form, and this step shall be noted in both

instruments.

When the law requires that a contract be in some form in order that it

may be valid or enforceable, or that a contract be proved in a certain

way, that requirement is absolute and indispensable.34 Here, the Deed of

Donation does not appear to be duly notarized. In page three of the deed,

the stamped name of Cresencio Tomakin appears above the words

Notary Public until December 31, 1983 but below it were the

typewritten words Notary Public until December 31, 1987. A closer

examination of the document further reveals that the

number 7 in 1987and Series of 1987 were merely superimposed.35 This

was confirmed by petitioners nephew Richard Unchuan who testified

that he saw petitioners husband write 7 over 1983 to make it appear

that the deed was notarized in 1987. Moreover, a Certification36 from

Clerk of Court Jeoffrey S. Joaquino of the Notarial Records Division

disclosed that the Deed of Donation purportedly identified in Book No. 4,

Document No. 48, and Page No. 35 Series of 1987 was not reported and

filed with said office. Pertinent to this, the Rules require a party

producing a document as genuine which has been altered and appears to

have been altered after its execution, in a part material to the question in

dispute, to account for the alteration. He may show that the alteration

was made by another, without his concurrence, or was made with the

consent of the parties affected by it, or was otherwise properly or

innocently made, or that the alteration did not change the meaning or

language of the instrument. If he fails to do that, the document shall, as in

this case, not be admissible in evidence.371avvphi1

Remarkably, the lands described in the Deed of Donation are covered by

TCT Nos. 7364538 and 73646,39 both of which had been previously

cancelled by an Order40 dated April 8, 1981 in LRC Record No. 5988. We

find it equally puzzling that on August 10, 1987, or six months after

Anita supposedly donated her undivided share in the lots to petitioner,

Page 15 of 99

the Unchuan Development Corporation, which was represented by

petitioners husband, filed suit to compel the Lozada sisters to surrender

their titles by virtue of a sale. The sum of all the circumstances in this

case calls for no other conclusion than that the Deed of Donation

allegedly in favor of petitioner is void. Having said that, we deem it

unnecessary to rule on the issue of laches as the execution of the deed

created no right from which to reckon delay in making any claim of

rights under the instrument.

Finally, we note that petitioner faults the appellate court for not

excluding the videotaped statement of Anita as hearsay evidence.

Evidence is hearsay when its probative force depends, in whole or in

part, on the competency and credibility of some persons other than the

witness by whom it is sought to be produced. There are three reasons

for excluding hearsay evidence: (1) absence of cross-examination; (2)

absence of demeanor evidence; and (3) absence of oath.41 It is a

hornbook doctrine that an affidavit is merely hearsay evidence where its

maker did not take the witness stand.42 Verily, the sworn statement of

Anita was of this kind because she did not appear in court to affirm her

averments therein. Yet, a more circumspect examination of our rules of

exclusion will show that they do not cover admissions of a party;43 the

videotaped statement of Anita appears to belong to this class. Section 26

of Rule 130 provides that "the act, declaration or omission of a party as

to a relevant fact may be given in evidence against him. It has long been

settled that these admissions are admissible even if they are

hearsay.44Indeed, there is a vital distinction between admissions against

interest and declaration against interest. Admissions against interest are

those made by a party to a litigation or by one in privity with or

identified in legal interest with such party, and are admissible whether

or not the declarant is available as a witness. Declaration against interest

are those made by a person who is neither a party nor in privity with a

party to the suit, are secondary evidence and constitute an exception to

the hearsay rule. They are admissible only when the declarant is

unavailable as a witness.45 Thus, a mans acts, conduct, and

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

declaration, wherever made, if voluntary, are admissible against him, for

the reason that it is fair to presume that they correspond with the truth,

and it is his fault if they do not.46However, as a further qualification,

object evidence, such as the videotape in this case, must be

authenticated by a special testimony showing that it was a faithful

reproduction.47 Lacking this, we are constrained to exclude as evidence

the videotaped statement of Anita. Even so, this does not detract from

our conclusion concerning petitioners failure to prove, by preponderant

evidence, any right to the lands subject of this case.

Anent the award of moral damages in favor of respondents, we find no

factual and legal basis therefor. Moral damages cannot be awarded in the

absence of a wrongful act or omission or fraud or bad faith. When the

action is filed in good faith there should be no penalty on the right to

litigate. One may have erred, but error alone is not a ground for moral

damages.48 The award of moral damages must be solidly anchored on a

definite showing that respondents actually experienced emotional and

mental sufferings. Mere allegations do not suffice; they must be

substantiated by clear and convincing proof.49 As exemplary damages

can be awarded only after the claimant has shown entitlement to moral

damages,50 neither can it be granted in this case.

Page 16 of 99

WE CONCUR:

CONCHITA CARPIO MORALES

Associate Justice

DANTE O. TINGA

Associate Justice

PRESBITERO J. VELASCO, JR.

Associate Justice

ARTURO D. BRION

Associate Justice

ATTESTATION

I attest that the conclusions in the above Decision had been reached in

consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of the opinion of

the Courts Division.

LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING

Associate Justice

Chairperson

CERTIFICATION

WHEREFORE, the instant petition is DENIED. The Decision dated

February 23, 2006, and Resolution dated April 12, 2006 of the Court of

Appeals in CA-G.R. CV. No. 73829 are AFFIRMED with MODIFICATION.

The awards of moral damages and exemplary damages in favor of

respondents are deleted. No pronouncement as to costs.

SO ORDERED.

LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING

Associate Justice

Chairperson

Pursuant to Section 13, Article VIII of the Constitution, and the Division

Chairpersons Attestation, I certify that the conclusions in the above

Decision had been reached in consultation before the case was assigned

to the writer of the opinion of the Courts Division.

REYNATO S. PUNO

Chief Justice

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

Footnotes

Rollo, pp. 35-51. Penned by Associate Justice Pampio A.

Abarintos, with Associate Justices Enrico A. Lanzanas and

Apolinario D. Bruselas, Jr. concurring.

1

Id. at 62-63.

Id. at 173-176. Dated July 6, 2000. Penned by Judge Soliver C.

Peras.

Page 17 of 99

SEC. 3. Docket and other lawful fees; proof of service of

petition. Unless he has theretofore done so, the petitioner shall

pay the corresponding docket and other lawful fees to the clerk

of court of the Supreme Court and deposit the amount of P500.00

for costs at the time of the filing of the petition. Proof of service of

a copy thereof on the lower court concerned and on the adverse

party shall be submitted together with the petition. (Emphasis

supplied.)

16

Id. at 95-155. Penned by Judge Leonardo B. Caares.

Records, Vol. I, pp. 355-358.

Id. at 351-354.

Id. at 347-350.

Records, Vol. II, pp. 187-188.

TSN, August 19, 1996, p. 8.

10

Records, Vol. I, p. 278.

11

Id. at 279.

12

Id. at 344-346.

13

Rollo, pp. 154-155.

14

15

Id. at 156-172.

Id. at 235-236.

SEC. 4. Contents of petition. The petition shall be filed in

eighteen (18) copies, with the original copy intended for the

court being indicated as such by the petitioner, and shall (a) state

the full name of the appealing party as the petitioner and the

adverse party as respondent, without impleading the lower

courts or judges thereof either as petitioners or respondents; (b)

indicate the material dates showing when notice of the judgment

or final order or resolution subject thereof was received, when a

motion for new trial or reconsideration, if any, was filed and

when notice of the denial thereof was received; (c) set forth

concisely a statement of the matters involved, and the reasons or

arguments relied on for the allowance of the petition; (d) be

accompanied by a clearly legible duplicate original, or a certified

true copy of the judgment or final order or resolution certified by

the clerk of court of the court a quo and the requisite number of

plain copies thereof, and such material portions of the record as

would support the petition; and (e) contain a sworn certification

against forum shopping as provided in the last paragraph of

section 2, Rule 42.

17

18

TSN, April 25, 1996, p. 6.

Sec. 14. No decision shall be rendered by any court without

expressing therein clearly and distinctly the facts and the law on

which it is based.

19

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

Yao v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 132428, October 24, 2000, 344

SCRA 202, 219.

outstanding and entitled to vote is owned and held by

citizens of the Philippines.

20

21

Id. at 218.

22

Rules of Court, Rule 36, Sec. 1

SECTION 1. Rendition of judgments and final orders.A

judgment or final order determining the merits of the

case shall be in writing personally and directly prepared

by the judge, stating clearly and distinctly the facts and

the law on which it is based, signed by him, and filed with

the clerk of the court.

J. G. Bernas, Constitutional Structure and Powers of

Government Notes and Cases Part I 632 (3rd ed., 2005).

23

24

25

26

Twin Towers Condominium Corporation v. Court of Appeals, G.R.

No. 123552, February 27, 2003, 398 SCRA 203, 222.

29

30

Records, Vol. II, pp. 375-376.

31

S. A.F. Apostol, Essentials of Evidence 438 (1991).

32

Records, Vol. II, p. 320.

33

Id. at 238-241.

34

Civil Code, Art. 1356.

35

Records, Vol. II, p. 357.

36

Id. at 248.

37

Rules of Court, Rule 132, Sec. 31.

38

Records, Vol. I, p. 295.

39

Id. at 296.

40

Id. at 408-418.

Id.

Rules of Court, Rule 131, Sec.3, par. (m).

Rules of Court, Rule 131, Sec.3, par. (o).

An Act to Promote Foreign Investments, Prescribe the

Procedures for Registering Enterprises Doing Business in the

Philippines, and for Other Purposes, approved on June 13, 1991.

Page 18 of 99

27

28

sec. 3. Definitions.As used in this Act:

(a) the term "Philippine National" shall mean a citizen of

the Philippines or a domestic partnership or association

wholly owned by citizens of the Philippines; or a

corporation organized under the laws of the Philippines

of which at least sixty percent (60%) of the capital stock

Estrada v. Desierto, G.R. Nos. 146710-15 & 146738, April 3,

2001, 356 SCRA 108, 128.

41

People v. Quidato, Jr., G.R. No. 117401, October 1, 1998, 297

SCRA 1, 8.

42

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

43

Estrada v. Desierto, supra at 131.

44

Id.

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

II F. D. Regalado, Remedial Law Compendium 491 (6th Revised

ed. 1989).

45

46

United States v. Ching Po, 23 Phil. 578, 583 (1912).

47

S. A.F. Apostol, Essentials of Evidence 63 (1991).

Filinvest Credit Corporation v. Mendez, No. L-66419, July 31,

1987, 152 SCRA 593, 601.

48

Quezon City Government v. Dacara, G.R. No. 150304, June 15,

2005, 460 SCRA 243, 256.

49

50

Id. at 257.

Page 19 of 99

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. No. 162886

August 11, 2008

HEIRS OF THE DECEASED SPOUSES VICENTE S. ARCILLA and JOSEFA

ASUNCION ARCILLA, namely: Aida Arcilla Alandan, Rene A. Arcilla,

Oscar A. Arcilla, Sarah A. Arcilla, and Nora A. Arcilla, now deceased

and substituted by her son Sharmy Arcilla, represented by their

attorney-in-fact, SARAH A. ARCILLA, petitioners,

vs.

MA. LOURDES A. TEODORO, respondent.

DECISION

AUSTRIA-MARTINEZ, J.:

Before the Court is a Petition for Review on Certiorari under Rule 45 of

the Rules of Court assailing the September 12, 2003 Decision1 of the

Court of Appeals (CA) and its Resolution2 dated March 24, 2004 in CAG.R. SP No. 72032.

The facts of the case are as follows:

On December 19, 1995, Ma. Lourdes A. Teodoro (respondent) initially

filed with the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Virac, Catanduanes an

application for land registration of two parcels of land located at

Barangay San Pedro, Virac, Catanduanes. The lots, with an aggregate

area of 284 square meters, are denominated as Lot Nos. 525-A and 525B, Csd.-05-010483-D of the Virac Cadastre. Respondent alleged that, with

the exception of the commercial building constructed thereon, she

Page 20 of 99

purchased the subject lots from her father, Pacifico Arcilla (Pacifico), as

shown by a Deed of Sale3 dated December 9, 1966, and that, prior

thereto, Pacifico acquired the said lots by virtue of the partition of the

estate of his father, Jose Arcilla evidenced by a document entitled

Extrajudicial Settlement of Estate.4 Respondent also presented as

evidence an Affidavit of Quit-Claim5 in favor of Pacifico, executed by

herein petitioners as Heirs of Vicente Arcilla (Vicente), brother of

Pacifico.

On February 7, 1996, the case was transferred to the Municipal Trial

Court (MTC) of Virac, Catanduanes in view of the expanded jurisdiction

of said court as provided under Republic Act No. 7691.6

In their Opposition dated August 19, 1996, petitioners contended that

they are the owners pro-indiviso of the subject lots including the building

and other improvements constructed thereon by virtue of inheritance

from their deceased parents, spouses Vicente and Josefa Arcilla; contrary

to the claim of respondent, the lots in question were owned by their

father, Vicente, having purchased the same from a certain Manuel

Sarmiento sometime in 1917; Vicente's ownership is evidenced by

several tax declarations attached to the record; petitioners and their

predecessors-in-interest had been in possession of the subject lots since

1906. Petitioners moved to dismiss the application of respondent and

sought their declaration as the true and absolute owners pro-indiviso of

the subject lots and the registration and issuance of the corresponding

certificate of title in their names.

Subsequently, trial of the case ensued.

On March 20, 1998, herein respondent filed a Motion for

Admission7 contending that through oversight and inadvertence she

failed to include in her application, the verification and certificate

against forum shopping required by Supreme Court (SC) Revised

Circular No. 28-91 in relation to SC Administrative Circular No. 04-94.

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

Petitioners filed a Motion to Dismiss Application8 on the ground that

respondent should have filed the certificate against forum shopping

simultaneously with the petition for land registration which is a

mandatory requirement of SC Administrative Circular No. 04-94 and that

any violation of the said Circular shall be a cause for the dismissal of the

application upon motion and after hearing.

Page 21 of 99

Aggrieved by the RTC Decision, petitioners filed a Petition for

Review14 with the CA. On September 12, 2003, the CA promulgated its

presently assailed Decision dismissing the Petition. Petitioners filed a

Motion for Reconsideration but the same was denied by the CA in its

Resolution15 dated March 24, 2004.

Hence, the herein petition based on the following grounds:

Opposing the motion to dismiss, respondents asserted that the

petitioners' Motion to Dismiss Application was filed out of time;

respondent's failure to comply with SC Administrative Circular No. 0494 was not willful, deliberate or intentional; and the Motion to Dismiss

was deemed waived for failure of petitioners to file the same during the

earlier stages of the proceedings.

On July 19, 1999, the MTC issued an Order9 denying petitioners' Motion

to Dismiss Application.

On June 25, 2001, the MTC rendered a

of which reads as follows:

Decision10

the dispositive portion

NOW THEREFORE, and considering all the above premises, the

Court finds and so holds that Applicant MA. LOURDES A.

TEODORO, having sufficient title over this land applied for

hereby renders judgment, which should be, as it is hereby

CONFIRMED and REGISTERED in her name.

IT IS SO ORDERED.11

Herein petitioners then filed an appeal with the Regional Trial Court of

Virac, Catanduanes. In its Decision12 dated February 22, 2002, the RTC,

Branch 43, of Virac, Catanduanes dismissed the appeal for lack of merit

and affirmed in toto the Decision of the MTC. Petitioners filed a Motion

for Reconsideration but it was denied by the RTC in its Order13 of July 22,

2002.

A. The Honorable Court of Appeals did not rule in accordance

with the prevailing rules and jurisprudence when it held that the

belated filing, after more than two (2) years and three (3)

months from the initial application for land registration, of a

sworn certification against forum shopping in Respondent's

application for land registration, constituted substantial

compliance with SC Admin. Circular No. 04-94.

B. The Honorable Court of Appeals did not rule in accordance

with prevailing laws and jurisprudence when it held that the

certification of non-forum shopping subsequently submitted by

respondent does not require a certification from an officer of the

foreign service of the Philippines as provided under Section 24,

Rule 132 of the Rules of Court.

C. The Honorable Court of Appeals did not rule in accordance

with prevailing laws and jurisprudence when it upheld the

decisions of the Regional Trial Court (RTC) and Municipal Trial

Court (MTC) that the lots in question were not really owned by

Petitioners' father Vicente S. Arcilla, contrary to the evidence

presented by both parties.

D. The Honorable Court of Appeals did not rule in accordance

with prevailing laws and jurisprudence when it sustained the

decision of the RTC which affirmed in toto the decision of the

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

MTC and in not reversing the same and rendering judgment in

favor of Petitioners.16

In their Memorandum, petitioners further raise the following issue:

Whether or not the Supreme Court may inquire into conclusions of facts

made by the Honorable Court of Appeals in the instant Petition.17

The Courts Ruling

The petition is bereft of merit.

The CA ruled correctly when it held that the belated filing of a

sworn certification of non-forum shopping was substantial

compliance with SC Administrative Circular No. 04-94.

Under the attendant circumstances in the present case, the Court cannot

uphold petitioners contention that respondent's delay of more than two

years and three months in filing the required certificate of non-forum

shopping may not be considered substantial compliance with the

requirements of SC Administrative Circular No. 04-94 and Section 5,

Rule 7 of the Rules of Court; that respondent's reasons of oversight and

inadvertence do not constitute a justifiable circumstance that could

excuse her non-compliance with the mandatory requirements of the

above-mentioned Circular and Rule; that subsequent compliance with

the requirement does not serve as an excuse for a party's failure to

comply in the first instance.

Section 5, Rule 7, of the Rules of Court provides:

Sec. 5. Certification against forum shopping. The plaintiff or

principal party shall certify under oath in the complaint or other

initiatory pleading asserting a claim for relief, or in a sworn

certification annexed thereto and simultaneously filed therewith:

Page 22 of 99

(a) that he has not theretofore commenced any action or filed

any claim involving the same issues in any court, tribunal or

quasi-judicial agency and, to the best of his knowledge, no such

other action or claim is pending therein; (b) if there is such other

pending action or claim, a complete statement of the present

status thereof; and (c) if he should thereafter learn that the same

or similar action or claim has been filed or is pending, he shall

report that fact within five (5) days therefrom to the court

wherein his aforesaid complaint or initiatory pleading has been

filed.

Failure to comply with the foregoing requirements shall not be

curable by mere amendment of the complaint or other initiatory

pleading but shall be cause for the dismissal of the case without

prejudice, unless otherwise provided, upon motion and after

hearing. The submission of a false certification or noncompliance with any of the undertakings therein shall constitute

indirect contempt of court, without prejudice to the

corresponding administrative and criminal actions. If the acts of

the party or his counsel clearly constitute willful and deliberate

forum shopping, the same shall be ground for summary

dismissal with prejudice and shall constitute direct contempt as

well as a cause for administrative sanctions.

This Rule was preceded by Circular No. 28-91, which originally required

the certification of non-forum shopping for petitions filed with this Court

and the CA; and SC Administrative Circular No. 04-94, which extended

the certification requirement for civil complaints and other initiatory

pleadings filed in all courts and other agencies.

In Gabionza v. Court of Appeals,18 this Court has held that Circular No. 2891 was designed to serve as an instrument to promote and facilitate the

orderly administration of justice and should not be interpreted with

such absolute literalness as to subvert its own ultimate and legitimate

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

objective or the goal of all rules of procedure which is to achieve

substantial justice as expeditiously as possible.19 The same guideline still

applies in interpreting what is now Section 5, Rule 7 of the 1997 Rules of

Civil Procedure.20

The Court is fully aware that procedural rules are not to be belittled or

simply disregarded, for these prescribed procedures insure an orderly

and speedy administration of justice.21 However, it is equally settled that

litigation is not merely a game of technicalities.22 Rules of procedure

should be viewed as mere tools designed to facilitate the attainment of

justice.23 Their strict and rigid application, which would result in

technicalities that tend to frustrate rather than promote substantial

justice, must always be eschewed.24 Even the Rules of Court reflect this

principle.25

Moreover, the emerging trend in our jurisprudence is to afford every

party-litigant the amplest opportunity for the proper and just

determination of his cause free from the constraints of technicalities.26

It must be kept in mind that while the requirement of the certificate of

non-forum shopping is mandatory, nonetheless the requirement must

not be interpreted too literally and thus defeat the objective of

preventing the undesirable practice of forum shopping.27 In Uy v. Land

Bank of the Philippines,28 the Court ruled, thus:

The admission of the petition after the belated filing of the

certification, therefore, is not unprecedented. In those cases

where the Court excused non-compliance with the requirements,

there were special circumstances or compelling reasons making

the strict application of the rule clearly unjustified. In the case at

bar, the apparent merits of the substantive aspects of the case

should be deemed as a "special circumstance" or "compelling

reason" for the reinstatement of the petition. x x x29

Page 23 of 99

Citing De Guia v. De Guia30 the Court, in Estribillo v. Department of

Agrarian Reform,31 held that even if there was complete non-compliance

with the rule on certification against forum-shopping, the Court may still

proceed to decide the case on the merits pursuant to its inherent power

to suspend its own rules on grounds of substantial justice and apparent

merit of the case.

In the instant case, the Court finds that the lower courts did not commit

any error in proceeding to decide the case on the merits, as herein

respondent was able to submit a certification of non-forum shopping.

More importantly, the apparent merit of the substantive aspect of the

petition for land registration filed by respondent with the MTC coupled

with the showing that she had no intention to violate the Rules with

impunity, as she was the one who invited the attention of the court to

the inadvertence committed by her counsel, should be deemed as special

circumstances or compelling reasons to decide the case on the merits.

In addition, considering that a dismissal contemplated under Rule 7,

Section 5 of the Rules of Court is, as a rule, a dismissal without prejudice,

and since there is no showing that respondent is guilty of forum

shopping, to dismiss respondent's petition for registration would entail a

tedious process of re-filing the petition, requiring the parties to resubmit the pleadings which they have already filed with the trial court,

and conducting anew hearings which have already been done, not to

mention the expenses that will be incurred by the parties in re-filing of

pleadings and in the re-conduct of hearings. These would not be in

keeping with the judicial policy of just, speedy and inexpensive

disposition of every action and proceeding.32

The certification of non-forum shopping executed in a foreign

country is not covered by Section 24, Rule 132 of the Rules of Court.

There is no merit to petitioners contentions that the verification and

certification subsequently submitted by respondent did not state the

Law 126 Evidence

Prof. Avena

35. NOTARIAL DOCUMENTS

country or city where the notary public exercised her notarial functions;

and that the MTC simply concluded, without any basis, that said notary

public was from Maryland, USA; that even granting that the verification