Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Knee Jerk Libertarianism by Frank Van Dunn

Uploaded by

Luis Eduardo Mella Gomez0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

212 views9 pagesSome thoughts about some vices in the libertarian movement by the Libertarian Political Philosopher and jurist Frank Van Dum

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentSome thoughts about some vices in the libertarian movement by the Libertarian Political Philosopher and jurist Frank Van Dum

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

212 views9 pagesKnee Jerk Libertarianism by Frank Van Dunn

Uploaded by

Luis Eduardo Mella GomezSome thoughts about some vices in the libertarian movement by the Libertarian Political Philosopher and jurist Frank Van Dum

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

The limits of knee-jerk libertarianism

and the battle for public space

Recently, there was an article on Sean Gabb's Libertarian

Alliance Blog with the scary title Book-burning; it's back 1

(posted October 17, 2013). The author, John Kersey, had

discovered that there is a market for obscene, depraved,

pornographic, cruel, scary fiction as well as a market for

denunciations of the same. Kersey wrote the article to

defend the porn market and to condemn the porndenunciation market, because

When we start banning books that take unpalatable,

unfashionable or simply wrong-headed viewpoints, we can forget

about freedom and indeed about any semblance of civilisation.

Of course, those markets are driven by people who like to

fantasise in print about gore, sex and violence in the one

case and about censoring and banning filthy books in the

other. In his defence of the porn fantasy market, Kersey

follows the predictable pattern, writing among other things

that there is no proven connexion between fantasy and

individuals acting out what they have read or imagined.

However, in attacking the market for censorship fantasies,

he seems to believe that there is a proven connexion

between the fantasies of those whom he calls selfimportant puritans and the actions of their readers. As he

provides no arguments for either claim, I shall remain

skeptical about both. However, I want to raise some

objections to his text. To the extent that it is meant to be an

argument, it strikes me as a non-sequitur. To the extent that

it is meant to express a libertarian point of view, it reduces

libertarianism to a caricature of what it purports to be, viz.

a principled defence of freedom as the right and proper

condition of human relations.

What struck me especially was the following passage in

Kersey's text:

"You should not think that I enjoy defending the obscene and

depraved. Such, however, seems to be the lot of the libertarian

these days, and we must go where we are needed."

Why should a libertarian feel he must go where he is

needed? Why should he feel he is needed to defend the

obscene and depraved with unsolicited hollow and pathetic

1

libertarianalliance.wordpress.com/2013/10/17/book-burning-itsback/#more-20840 (Posted on 17 October, 2013).

rhetoric? Do not legions of willing lawyers stand by to

defend those among the obscene and depraved who feel

they need defending? Besides, judging by market tests,

porn peddlers can very well fend for themselves. In the

present environment, it is likely that they will profit from

any mention in the mass media, be it positive or negative in

tone. So, where is the need to which Kersey's article

pretends to respond? I consider myself a libertarian and

would like to see many more libertarians than there are

now, but I will not defend pornographers against their

critics, and I will not assume that those critics are would-be

tyrants merely because they indulge in hyperbole such as

Ban that book! and not in hyperbole such as Criticising

pornography leads to slavery and the end of even a

semblance of civilisation. My advice to John Kersey is, If

you dont like defending the obscene and depraved, do not

defend them. When we ever reach that wonderful situation

where defending pornographers is the top priority for

libertarians, youll have ample opportunity to set up or

contribute money to a legal-defence fund for the purveyors

of smut. Still, even then, there will be a difference between

defending pornographers against those who want to bring

down the full force of the law upon them and defending

pornography.

Ironically, Kersey presents himself as a libertarian

traditionalist Catholic. Doesn't a libertarian Catholic have

better things to do than to defend pornographers against

those who express their intense dislike for them? With its

Hate the sin; love the sinner, its ethics of love and

forgiveness, its claim that the neither the Church of God

nor any of its members can be subject to any secular

authority in matters of faith or conscience, and its general

requirement

of

humility,

Catholicism

has

enough

libertarianism in its core beliefs to give a Catholic ample

occasion to air libertarian views without sounding like any

other mindless free speech intellectual, unable or

unwilling to distinguish reasoned speech from grunts and

growls.

To reach his dire conclusion about the end of freedom and

civilisation, Kersey uses the fallacy of the slippery slope or

the thin edge of the wedge: It starts with banning

pornography, then it goes on to banning revisionist history,

white nationalist texts and material that is critical of the

Jewish people, and it ends with tyranny and barbarism.

Well, maybe it does, most likely it doesn't but in any case,

saying it is so does not make it so. Calls for banning

something often go nowhere; official bans are not always

effectively enforced; and in the case of printed or digitised

texts, their effective enforcement always was and still is

virtually impossible. Unless they are outright fools, those

who explicitly call for banning some books are very likely

expressing nothing more than their strong opposition to the

contents of those books. Surely, they should not be denied

the freedom of expressing their opinion, merely because

there is always a risk that one or other politician will start

to push for legal sanctions against authors, publishers or

readers of unpalatable material. Kersey does not even try to

make the case that calls to ban pornography are really calls

to persecute pornographers or their readers as criminals.

Obviously, Kersey is not mounting a campaign to outlaw

criticism of pornography. We should not assume that his

text is really a call for treating critics of pornography or

their readers as criminals. He is merely expressing his

loathing for self-important puritans, who take offense at

publications that aim to offend the tastes and sensibilities

or at least, the publicly avowed tastes and sensibilities

of what is arguably a vast majority of the population. That

there might be a risk that one or other politician will start

to push for legal sanctions against puritans does not

appear to be his concern. Still, he uninhibitedly dramatises

and exaggerates the influence and sinister designs of those

puritans, indulging himself in hyperbole about the end of

freedom and civilisation (which, if it were anything but

hyperbole, would be a good enough reason for outlawing

criticism of pornography). He thereby distracts attention

from the fact that the supposed slippery slope leading from

calls to ban pornography to the end of civilisation is

insignificant compared with the broad avenues to decivilisation that have been constructed already by the ruling

coalition of ideological and corporate growth addicts, debt

peddlers and crusaders for politically correct pense

unique.

Was the historical advance of the idea of freedom in the

West (an advance that ended more than a hundred years

ago) ever aided and abetted by the defence of obscenity or

depravity, or even of fantasies of the same? Such defences

may have been side-effects, but they were certainly not

causes of the advance of liberty. The theme of the relation

between sex and freedom is an important one, but it is not

simply a variation on the theme of freedom of speech. Sixty

years ago, Aldous Huxley (in the foreword to the post-WWII

re-edition of Brave New World) noted how readily people

accept the grant of sexual freedom or fantasies thereof as

adequate compensation for the loss of other freedoms

(economic, political, educational). It may be true that there

is no proven connexion between fantasy and individuals

acting out what they have read or imagined; it may even

be true that fans [of horror movies] seem to be on the

whole well-balanced and often highly moral individuals.

However, those truths (if that is what they are) do not mean

that freedom thrives in societies where escapist fantasies

are cheap items of mass consumption and criticism of their

public availability is publicly denounced as self-important

Puritanism leading to tyranny and barbarism.

The immediate objects of Kersey's ire are an obscure

publication, The Kernel, and a few articles in a mainstream

newspaper, The Mail, but he seems particularly upset about

the fact that commercial providers such as Amazon and

eBay, anxious to protect their reputation, respond or claim

to respond to real or imagined public outrage. Now, as

those providers are private corporations, one would expect

a libertarian to say no more than It's their business. I am

not going to tell them what they may or may not try to sell,

or which public-relations policies they should or should not

adopt. That was the typical libertarian reaction to the late

and now sainted Steve Jobs's refusal to permit an app

proposed by defenders of traditional marriage on the

ground that it might be offensive to guess-who. Kersey does

not refer to that episode, nor does he refer to the fact that

there are rather pervasive calls, and in some countries legal

means, not only for banning expressions of religious or just

plain

folksy

beliefs

about

abortion,

euthanasia,

homosexuality, same-sex marriage and gay parenting as

well as expressions of popular sentiment and prejudices

about certain minorities, but also for fining, jailing or

otherwise harassing those who express such beliefs. Surely,

every person has a right to ban any book from his library or

reading list, just as every commercial publisher has a right

to ban any book from his catalogue. It does not follow that

every person has a right to inflict legal punishment on those

who produce or read books he does not like. Why, then,

should we assume as Kersey apparently does that

anybody who calls on others to ban pornography is calling

for the persecution of pornographers and their readers?

Advocating censorship is not the same as legally

imposing censorship, just as publishing a must read list of

books is not the same as force-reading the listed books to

people (usually schoolchildren) who would not look at them

otherwise. On the level of abstract principle, obliging young

people to read Orwell's 1984 is as objectionable as obliging

them to read Fifty Shades of Grey, and advocating banning

the latter from school libraries as objectionable as

advocating banning the former. But life is not led on the

level of abstract principle, and freedom is to be enjoyed in

real life by real people in real contexts they share with

other real people. I do not know if John Kersey has children,

but if he has, how would he react if they called him a tyrant

and a barbarian because he had told them that he would

not permit them to bring certain bad books into the house?

The point is that everybody who is anybody (parent, friend,

teacher, publisher, employer, therapist) is bound indeed,

morally bound to become censorious on at least some

occasions. On those occasions, choices have to be made,

and they'd better be the right choices.

There is nothing wrong with urging people to read good

books and urging them not to read bad books. Prosecuting

people for the books they write or read is certainly wrong,

but Kersey provides no evidence that either The Kernel,

The Mail, Amazon or eBay are in a position or about to start

prosecuting people.

Abstract libertarian principles not only freedom of

expression and freedom of reading what one wants

refer to the interactions among adults who are perfect

strangers to one another. Like all civilised people,

libertarians prefer to settle disagreements and conflict by

negotiation and ultimately by an appeal to reason. The

larger the common ground between the parties to a conflict

is, the easier it is to arrive at a solution that conforms to

their shared notions of what is true and right. The hard

cases are those where there is no common ground other

than the recognition by every party that all the parties to

the conflict are human persons like them different in all

respects but their humanness. The rationally insoluble

cases are those where at least one of the parties refuses to

recognise the others as human persons at all. The law of

the jungle solves the rationally insoluble cases;

libertarianism solves the hard cases; and appeals to a

common store of shared beliefs about what is true or right

solve the other cases. The philosophical interest of

libertarianism lies in the fact that it is able to provide

principles of conflict resolution that presuppose as little

common ground between human persons as is compatible

with their consciousness of being persons and their ability

to recognise another person when they meet one.

Libertarianism requires of its adherents only that they

respect one another, and indeed all others, as human

persons, different as far as their individualities are

concerned but alike in being human.

However, despite the anonymity, alienation and

atomisation of contemporary Western society, most people

live most of their lives among family, neighbours, friends,

close associates, and in particular communities and

particular societies. They are involved in contexts that are

rife with customs, traditions, opinions, norms and values

that constitute much of their way of life and require some

kind of censorship if they are to be maintained. Those are

contexts in which the word we is more than pompous

rhetoric. In some of them, We must go where we are

needed may even be true, but when Kersey writes about

we, libertarians, I am inclined to think, Speak for

yourself, man; don't tell me where I must go.

Libertarian principles identify the least common ground

of rights and obligations between adult perfect strangers

who have nothing but their being human in common. That

is why those principles work so well for economic

transactions in an open-market setting, where the seller

and the buyer typically have no knowledge of and no

interest in one another's particular circumstances,

intentions, motives, obligations and responsibilities to

others and no opportunity to enforce Deal exclusively

with me (and only on my terms) policies on others. It is

also why they work so well against the State, which knows

no other policies. The logic of markets and the logic of

State action rest on what Philip Wicksteed called nontuism (literally, not-youism) mutual non-tuism in the one

case and unilateral non-tuism in the other. Now, it is true

that cash-and-carry deals require no knowledge of who and

what the seller or buyer is and what he is up to. However,

most market transactions involve credit or trust, which

typically requires quite a lot of such knowledge. Moreover,

they require not only trust on a personal level, but also

trust in the general respect for and effective enforceability

of rules of property, contractual obligation and liability for

torts. If the latter sort of trust is not sustained by ingrained

traditions of self-discipline, self-restraint and readiness to

support the victims of injustice against the perpetrators of

injustice; if it is not sustained by cultural and moral capital

built up over generations then they must be sustained by

common fear of a single powerful authority (as Thomas

Hobbes argued) but then there is no longer a fortification

of justice, only a justification of force (as Blaise Pascal

noted).

Libertarians who ignore the constraints of culture run the

risk of playing into the hands of the State. They do so when

they move from the obvious Never treat any person with

less respect than you owe a perfect stranger to the

dubious Treat every person as if he were a perfect

stranger or from Dont use force except in self-defence

to Defend whatever does not involve the use of force in

short, when they move from discerning and discriminating

libertarianism to knee-jerk libertarianism. Every thing we

do or say ends up strengthening or weakening one or other

attitude, and at any time, the preponderant mix of attitudes

determines the degree of freedom we can actually enjoy.

The ability to recite abstract libertarian principles is not an

excuse for not being concerned with questions of right or

wrong, good or evil, and cause and effect. No doubt,

physical aggression against persons and their justly

acquired property is evil, but homo sapiens is an inventive

species. Many of its specimens are quite proficient at

finding ways to do much and lasting evil without engaging

in physical aggression. Isn't it amazing how much evil

European states have been able to do since the Second

World War, even to their own populations, with only a

minimal display of physical might?

The application of libertarian principles to real life

situations is especially difficult as far as conduct in public

spaces is concerned places where one is likely to meet

people with whom one may not have much in common

because such places are accessible to all and sundry. Some

libertarians assert that there is no problem, as there will

not be any public places in a libertarian society and every

space will be governed at the discretion of its private

owner. They proclaim as their ideal of liberty that you have

no freedom to go anywhere without obtaining a passport

from, paying tribute to and agreeing to the conditions

imposed by every owner along any way to your destination.

To me, that would be a society without freedom. In what

sense of the word would it be libertarian? Libertarian

freedom without public spaces is a chimera. Unfortunately,

theorizing about the role of public spaces in free societies

and free markets is rarely considered a priority of

libertarian thought.

Whether public spaces are supervised by agents of the

State or by private owners, they need to be regulated to

provide access and use on equal terms to everybody who is

capable of using them without causing damage and willing

to use them without harassing or importuning other users.

In short, whether privately owned or not, public spaces

should be recognised as different from private spaces. A

space that is exploited only for the private benefit of the

individual or corporate owner is not a public space at all.

Discriminatory practices in providing access to your home,

caf or cinema do not belong in the same category as

discriminatory practices in providing access to a road or

street (other than a cul-de-sac or the access road of a

gated community such as a monastery or a holiday

resort). The same behaviour between consenting adults that

is within their rights, if it is confined to a private room or an

isolated place, need not be within their rights, if they

engage in it in a public place even if its owner or

manager has not explicitly made abstention from that

behaviour a condition of entry.

Libertarian freedom includes not only the availability of

and freedom of movement in public spaces but also the

freedom of parents and guardians to raise and educate

children without having to lock them up to shield them from

uncontrollable improper influences and provocations. The

traditional solution was that conduct in public places should

conform to common rules of decency and good manners

and to the requirements of normal use rather than to the

whim of whoever happens to be the manager or the owner

or to the whim of an organised pressure group of users. It

would be wrong to underestimate the effect of safe and

inoffensive public spaces in fostering an appreciation of

freedom as an obvious way of life. Where else can children

learn to be comfortable among strangers without being

under the discretionary authority of someone else, be it a

government or a private owner?

The requirements of decency, good manners and normal

use apply not only to personal behaviour and action in

public spaces but also to messages posted on billboards in

places open to the public. This is relevant for discussions

about censorship of pornography and other unpalatable

things. Is anyone's freedom curtailed by restrictions in

public places on pornography or advertisements for

pornography, or on publishing insults and calls for violence?

Is insisting on good manners in public behaviour a symptom

of self-important Puritanism? Was Kersey's argument that

we, libertarians, need to rise to the defence of the public

performance or advertisement of anything whatsoever that

consenting adults have a right to do to one another in

private? I hope not.

Modern technology, from broadcasting to the Internet,

has vastly expanded the range of public space. It is true

that the consumers usually access those virtual spaces from

within their personal private space, and that they can easily

switch to another channel or screen whenever they see or

hear something they find intolerably offensive. Still, the

producers make their broadcasts and websites publicly

available to children as well adults, innocents as well as

criminals, people of character as well as spineless

weaklings, the washed as well as the unwashed. To their

credit, many producers insist on common decency, good

manners and normal use and actively censor unpalatable

content, but many do not. Criticising and even calling for a

boycott of the latter hardly amount to subverting the cause

of freedom, much less precipitating the end of civilised life.

Frank van Dun

25 October 2013

You might also like

- Homosexuality “It’S Not What You Think It Is”: Shattering the Myths Behind the Misunderstanding.From EverandHomosexuality “It’S Not What You Think It Is”: Shattering the Myths Behind the Misunderstanding.No ratings yet

- Summary of Woke Racism How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America by John McWhorterFrom EverandSummary of Woke Racism How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America by John McWhorterRating: 1.5 out of 5 stars1.5/5 (6)

- Livings Like A HeterosexaulDocument111 pagesLivings Like A HeterosexaulMississippi Charles BevelNo ratings yet

- Conscience and Its Enemies: Confronting the Dogmas of Liberal SecularismFrom EverandConscience and Its Enemies: Confronting the Dogmas of Liberal SecularismRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Ego and Society S.E. ParkerDocument7 pagesEgo and Society S.E. ParkerolderpigNo ratings yet

- By Any Other Name: Exposing the Deception, Mythology, and Tragedy of SecularismFrom EverandBy Any Other Name: Exposing the Deception, Mythology, and Tragedy of SecularismNo ratings yet

- 2.1 Jeremy Waldron - The Harm in Hate Speech (Cap 4)Document48 pages2.1 Jeremy Waldron - The Harm in Hate Speech (Cap 4)JuanPabloMontoyaPepinosaNo ratings yet

- Xenophon's Socratic Education: Reason, Religion, and the Limits of PoliticsFrom EverandXenophon's Socratic Education: Reason, Religion, and the Limits of PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Anti-Blackness and ColonalismDocument15 pagesAnti-Blackness and ColonalismDarrian CarrollNo ratings yet

- A Most Peculiar Kind of LiberalDocument11 pagesA Most Peculiar Kind of LiberalneocapNo ratings yet

- Conform or Be Cast Out: The (Literal) Demonization of NonconformistsFrom EverandConform or Be Cast Out: The (Literal) Demonization of NonconformistsNo ratings yet

- Rowan AtkinsonDocument4 pagesRowan AtkinsonMircea SilaghiNo ratings yet

- "We the Sheeple": "If This Book Does Not Make You Mad, Nothing Will"From Everand"We the Sheeple": "If This Book Does Not Make You Mad, Nothing Will"No ratings yet

- Divided We StandDocument11 pagesDivided We Standapi-474980756100% (1)

- Book Review Hiding From Humanity BDocument3 pagesBook Review Hiding From Humanity BLisaNo ratings yet

- In Search of the Common Good: Guideposts for Concerned CitizensFrom EverandIn Search of the Common Good: Guideposts for Concerned CitizensNo ratings yet

- Cancel Culture: The Latest Attack on Free Speech and Due ProcessFrom EverandCancel Culture: The Latest Attack on Free Speech and Due ProcessRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Capitalism vs. Freedom: The Toll Road to SerfdomFrom EverandCapitalism vs. Freedom: The Toll Road to SerfdomRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Was Frankenstein Really Uncle Sam? Vol. Viii: Notes on the State of the Declaration of IndependenceFrom EverandWas Frankenstein Really Uncle Sam? Vol. Viii: Notes on the State of the Declaration of IndependenceNo ratings yet

- Making Gay Okay: How Rationalizing Homosexual Behavior Is Changing EverythingFrom EverandMaking Gay Okay: How Rationalizing Homosexual Behavior Is Changing EverythingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- Nonviolence Ain't What It Used To Be: Unarmed Insurrection and the Rhetoric of ResistanceFrom EverandNonviolence Ain't What It Used To Be: Unarmed Insurrection and the Rhetoric of ResistanceNo ratings yet

- The Limits Of Atheism Or, Why should Sceptics be Outlaws?From EverandThe Limits Of Atheism Or, Why should Sceptics be Outlaws?No ratings yet

- Allow Me to Retort: A Black Guy’s Guide to the ConstitutionFrom EverandAllow Me to Retort: A Black Guy’s Guide to the ConstitutionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Pink Swastika Conclusion and EpilogueDocument22 pagesPink Swastika Conclusion and EpilogueshelleyNo ratings yet

- Was Jesus a Socialist?: Why This Question Is Being Asked Again, and Why the Answer Is Almost Always WrongFrom EverandWas Jesus a Socialist?: Why This Question Is Being Asked Again, and Why the Answer Is Almost Always WrongRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Guess Who's Coming to Dinner Now?: Multicultural Conservatism in AmericaFrom EverandGuess Who's Coming to Dinner Now?: Multicultural Conservatism in AmericaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- WHERE WE STUMBLE - Dismantling Rape Sub-CultureDocument48 pagesWHERE WE STUMBLE - Dismantling Rape Sub-CultureGrawpNo ratings yet

- The Coming Woke Catastrophe: A Critical Examination of Woke CultureFrom EverandThe Coming Woke Catastrophe: A Critical Examination of Woke CultureNo ratings yet

- American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War On AmericaFrom EverandAmerican Fascists: The Christian Right and the War On AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (226)

- Domestic Intimacies: Incest and the Liberal Subject in Nineteenth-Century AmericaFrom EverandDomestic Intimacies: Incest and the Liberal Subject in Nineteenth-Century AmericaRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- White Right and LibertarianDocument125 pagesWhite Right and LibertarianMarcus ViníciusNo ratings yet

- An Unexpected Journal: Thoughts on "The Abolition of Man": Volume 1, #1From EverandAn Unexpected Journal: Thoughts on "The Abolition of Man": Volume 1, #1No ratings yet

- The Cunning of Freedom: Saving the Self in an Age of False IdolsFrom EverandThe Cunning of Freedom: Saving the Self in an Age of False IdolsNo ratings yet

- Fire in the Streets: How You Can Confidently Respond to Incendiary Cultural TopicsFrom EverandFire in the Streets: How You Can Confidently Respond to Incendiary Cultural TopicsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Ericsson Macro4Document12 pagesEricsson Macro4Leiria CovetNo ratings yet

- Ethics Character and VirtueDocument17 pagesEthics Character and VirtueChad WhiteheadNo ratings yet

- A Critique of Socialism: Read Before The Ruskin Club of Oakland California, 1905From EverandA Critique of Socialism: Read Before The Ruskin Club of Oakland California, 1905No ratings yet

- You Can't Say That!: The Demise of Free Thought in AustraliaFrom EverandYou Can't Say That!: The Demise of Free Thought in AustraliaNo ratings yet

- The History of Corporal Punishment - A Survey of Flagellation in Its Historical Anthropological and Sociological AspectsFrom EverandThe History of Corporal Punishment - A Survey of Flagellation in Its Historical Anthropological and Sociological AspectsNo ratings yet

- Best Essay Ever WrittenDocument10 pagesBest Essay Ever Writtenafibzdftzaltro100% (2)

- Libertarian Forum: BakkeDocument8 pagesLibertarian Forum: BakkeSubverzivni TraktorNo ratings yet

- What White People Can Do Next: From Allyship to CoalitionFrom EverandWhat White People Can Do Next: From Allyship to CoalitionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- 1 Wordsworth Donisthorpe LawDocument65 pages1 Wordsworth Donisthorpe LawAkhyaNo ratings yet

- On Liberty: John Stuart Mill 1843Document17 pagesOn Liberty: John Stuart Mill 1843Joe Hicks100% (1)

- Table: List of VariablesDocument10 pagesTable: List of VariablesLuis Eduardo Mella GomezNo ratings yet

- MyfileDocument2 pagesMyfileLuis Eduardo Mella GomezNo ratings yet

- 14159-Article Text-11140-1-10-20150702 PDFDocument9 pages14159-Article Text-11140-1-10-20150702 PDFLuis Eduardo Mella GomezNo ratings yet

- HPV-induced Recurrent Laryngeal Papillomatosis: Rationale For Adjuvant Fatty Acid TherapyDocument7 pagesHPV-induced Recurrent Laryngeal Papillomatosis: Rationale For Adjuvant Fatty Acid TherapyLuis Eduardo Mella GomezNo ratings yet

- Taxation in D.RDocument5 pagesTaxation in D.RLuis Eduardo Mella GomezNo ratings yet

- CV Carles Sirera 2013Document6 pagesCV Carles Sirera 2013Luis Eduardo Mella GomezNo ratings yet

- Test Statistics Fact SheetDocument4 pagesTest Statistics Fact SheetIra CervoNo ratings yet

- MOA Agri BaseDocument6 pagesMOA Agri BaseRodj Eli Mikael Viernes-IncognitoNo ratings yet

- Data Science Online Workshop Data Science vs. Data AnalyticsDocument1 pageData Science Online Workshop Data Science vs. Data AnalyticsGaurav VarshneyNo ratings yet

- Designing A Peace Building InfrastructureDocument253 pagesDesigning A Peace Building InfrastructureAditya SinghNo ratings yet

- Risteski Space and Boundaries Between The WorldsDocument9 pagesRisteski Space and Boundaries Between The WorldsakunjinNo ratings yet

- (Music of The African Diaspora) Robin D. Moore-Music and Revolution - Cultural Change in Socialist Cuba (Music of The African Diaspora) - University of California Press (2006) PDFDocument367 pages(Music of The African Diaspora) Robin D. Moore-Music and Revolution - Cultural Change in Socialist Cuba (Music of The African Diaspora) - University of California Press (2006) PDFGabrielNo ratings yet

- The Handmaid's Tale - Chapter 2.2Document1 pageThe Handmaid's Tale - Chapter 2.2amber_straussNo ratings yet

- E 05-03-2022 Power Interruption Schedule FullDocument22 pagesE 05-03-2022 Power Interruption Schedule FullAda Derana100% (2)

- Psc720-Comparative Politics 005 Political CultureDocument19 pagesPsc720-Comparative Politics 005 Political CultureGeorge ForcoșNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Violence in IndiaDocument17 pagesApproaches To Violence in IndiaDeepa BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Arctic Beacon Forbidden Library - Winkler-The - Thousand - Year - Conspiracy PDFDocument196 pagesArctic Beacon Forbidden Library - Winkler-The - Thousand - Year - Conspiracy PDFJames JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Biosphere Noo Sphere Infosphere Epistemo PDFDocument18 pagesBiosphere Noo Sphere Infosphere Epistemo PDFGeorge PetreNo ratings yet

- Invitation 2023Document10 pagesInvitation 2023Joanna Marie Cruz FelipeNo ratings yet

- NetStumbler Guide2Document3 pagesNetStumbler Guide2Maung Bay0% (1)

- Public Service Media in The Networked Society Ripe 2017 PDFDocument270 pagesPublic Service Media in The Networked Society Ripe 2017 PDFTriszt Tviszt KapitányNo ratings yet

- WHAT - IS - SOCIOLOGY (1) (Repaired)Document23 pagesWHAT - IS - SOCIOLOGY (1) (Repaired)Sarthika Singhal Sarthika SinghalNo ratings yet

- Rita Ora - Shine Ya LightDocument4 pagesRita Ora - Shine Ya LightkatparaNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Grade 5 Quarter 2: Answer KeyDocument4 pagesMathematics Grade 5 Quarter 2: Answer KeyApril Jean Cahoy100% (2)

- Spelling Master 1Document1 pageSpelling Master 1CristinaNo ratings yet

- Cruz-Arevalo v. Layosa DigestDocument2 pagesCruz-Arevalo v. Layosa DigestPatricia Ann RueloNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Political ScienceDocument18 pagesIntroduction To Political Sciencecyrene cayananNo ratings yet

- Administrator's Guide: SeriesDocument64 pagesAdministrator's Guide: SeriesSunny SaahilNo ratings yet

- How To Create Partner Function in SAP ABAPDocument5 pagesHow To Create Partner Function in SAP ABAPRommel SorengNo ratings yet

- Speech by His Excellency The Governor of Vihiga County (Rev) Moses Akaranga During The Closing Ceremony of The Induction Course For The Sub-County and Ward Administrators.Document3 pagesSpeech by His Excellency The Governor of Vihiga County (Rev) Moses Akaranga During The Closing Ceremony of The Induction Course For The Sub-County and Ward Administrators.Moses AkarangaNo ratings yet

- RWE Algebra 12 ProbStat Discrete Math Trigo Geom 2017 DVO PDFDocument4 pagesRWE Algebra 12 ProbStat Discrete Math Trigo Geom 2017 DVO PDFハンター ジェイソンNo ratings yet

- 67-Article Text-118-1-10-20181206Document12 pages67-Article Text-118-1-10-20181206MadelNo ratings yet

- Business Administration: Hints TipsDocument11 pagesBusiness Administration: Hints Tipsboca ratonNo ratings yet

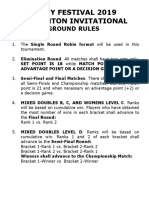

- Ground Rules 2019Document3 pagesGround Rules 2019Jeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- Grade 7 1ST Quarter ExamDocument3 pagesGrade 7 1ST Quarter ExamJay Haryl PesalbonNo ratings yet

- Michel Agier - Between War and CityDocument25 pagesMichel Agier - Between War and CityGonjack Imam100% (1)