Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rural Latino Farmworker Fathers' Understanding of Children's

Uploaded by

Ade AriCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rural Latino Farmworker Fathers' Understanding of Children's

Uploaded by

Ade AriCopyright:

Available Formats

NIH Public Access

Author Manuscript

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 December 20.

Published in final edited form as:

Pediatr Dent. 2010 ; 32(5): 400406.

Rural Latino farmworker fathers' understanding of children's

oral hygiene practices

$watermark-text

Matthew A. Swan, BA1 [Research Analyst], Judith C. Barker, PhD2,* [Professor], and Kristin

S. Hoeft, MPH3 [Research Analyst]

1School of Dentistry, University of California San Francisco, 707 Parnassus Ave., San Francisco,

CA 94143, USA

2Department

of Anthropology, History, & Social Medicine and Center to Address Disparities in

Childrens Oral Health, University of California San Francisco, 3333 California Street, Suite 485,

San Francisco, CA 94143-0850, USA

3Department

of Preventive & Restorative Dental Sciences and Department of Anthropology,

History, & Social Medicine and Center to address Disparities in Childrens Oral Health, University

of California San Francisco, 3333 California Street, Suite 485, San Francisco, CA 94143-0850,

USA

$watermark-text

Abstract

PurposeTo examine rural Latino fathers' understanding of their children's oral hygiene

practices.

MethodsA convenience sample (n=20) of fathers from a small agricultural city in California

was recruited in their homes. Individual qualitative interviews in Spanish were conducted.

Interviews were audio-taped, translated and transcribed. Codes were developed and the text

analyzed for recurrent themes.

$watermark-text

ResultsFathers came from Mexico (n=15) and El Salvador (n=5). Fathers had very little

understanding of the etiology and clinical signs of dental caries. Overall, 18 of 19 fathers reported

that their wife was primarily responsible for taking care of the children's hygiene. Fathers agreed

that children's teeth should be cared for from a young age, considered to be after 2 years. The

fathers described very minimal hygiene assistance given to children by either parent, and often

considered a verbal reminder to be sufficient assistance. Fathers generally thought a child did not

need supervision after about age 4 (range 1 to 11 years).

ConclusionsWhile rural Latino fathers might not actively participate in their children's oral

hygiene, they do place value on it. Men are supportive of dental treatments, albeit later than

recommended. Educational messages aimed at these families will disseminate to the fathers,

indirectly.

Keywords

Latinos; children; fathers; oral health; knowledge

Introduction

Disproportionate dental disease among the Latino population is well documented. (In this

paper, the term Latino is used to refer to those who self-identify as either Hispanic or

Corresponding author. barkerj@dahsm.ucsf.edu, Tel: 415-476-7241, Fax: 415-476-6715.

Swan et al.

Page 2

Latino as overall, in California, where this study took place, no preference exists between

the two terms.)1 Oral health problems are highly prevalent among migrant farmworker

populations,2,3 with particularly high rates of early childhood caries (ECC) among their

children.46 Research on this topic has elucidated several reasons accounting for these stark

disparities, including barriers to dental care,7, 8 poor parental understanding of caries

etiology or prevention,3,9 low value given to primary teeth,10 and inadequate engagement of

children in oral hygiene practices at home.11, 12

$watermark-text

$watermark-text

While some studies have explored how Latino mothers understand and make decisions

regarding their childrens oral health,1317 thus far there is no published research on Latino

fathers understanding of the same. This is likely due to several factors: that men are a

difficult population to recruit and interview during usual weekday work hours, that some

men are uncomfortable being interviewed by women researchers, and a well-established

assumption that depicts the Latino mother as the primary parent interfacing with children,

especially with young children, with the Latino father as peripheral to family childrearing

responsibilities.18,19 This perspective coincides with a more traditional view of Latino

fathers, one that portrays them as strict, reserved, and authoritarian. Mothers, on the other

hand, are traditionally assumed to be quiet, submissive, and subservient in the home.20 This

traditional view is being challenged by contemporary research, however, that has found

Latino couples to be more egalitarian in their distribution of responsibilities. Studies show

that Latino fathers do spend time with their children as nurturing caregivers and active

teachers.2123 Nevertheless, it is clear that despite this apparent increase in father

involvement, in Latino families, mothers still carry the majority of the household burden and

are their childrens principal caretakers responsible for their health.2226

$watermark-text

There is a very small body of research on fathers involvement in childrens oral health.

Broder and colleagues examined the role of 60 inner-city African American fathers in New

Jersey in child rearing and oral health practices, with the goal of evaluating the potential of

fathers to effect change if they were recipients of oral health promotion interventions.27 This

quantitative survey reported that 95% of fathers indicated interest in learning more about

ways to help their children have healthy teeth and gums. These fathers were involved in

their childrens oral hygiene routines with half reporting shared or sole responsibility for

brushing their childrens teeth. While fathers had good factual understanding of their

childrens oral health care practices, they lacked confidence in their ability to prevent

cavities or to stop behaviors that put their children at risk for cavities. In contrast, Reisine

and co-workers reported that 52 African American men living in Detroit claimed good

access to social support and demonstrated a high perceived self-efficacy to take care of their

child's teeth, but possessed limited knowledge on how to prevent oral health problems.28

These small scale studies demonstrate a wide variation in findings, but support the

development and testing of oral health promotion programs which include AfricanAmerican fathers. These issues, especially knowledge of oral health preventive activities,

have not been explored with respect to fathers from other ethnic groups, including Latino

groups.

The dearth of knowledge about Latino fathers is a void that must be filled, as these men

assume critical roles in the Latino family structure. Fathers have long been regarded as the

final decision makers within their households, particularly concerning financial matters.2931

As guardian of the family finances (including insurance and health expenditures),

transportation, and other important resources, the father is pivotal in supporting womens

decisions and providing for the familys needs. This paper examines a particular group rural Latino farmworker fathers understanding of their childrens oral hygiene practices. A

better understanding of Latino fathers views of their childrens oral health is essential if we

are to improve care provided to this population.

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 December 20.

Swan et al.

Page 3

Methods

We used an in-depth qualitative approach to learn more about rural Latino fathers

understanding of and practices related to their childrens oral hygiene. This approach

consisted of 12 hour long semi-structured, open-ended interviews carried out in each of the

fathers homes.

$watermark-text

The study was conducted in a small rural city with a predominantly Latino population, in

Californias agricultural Central Valley. The target population was farmworking fathers who

lived in this city and were: 1) caregivers of children aged 10 or less, with the aim that their

youngest child be aged 5 or less; 2) first- or second- generation immigrants from Mexico or

Central America. We recruited the convenience sample of participants partially from a

randomized list of household addresses generated by a partner study on farmworker

occupational health, but principally through personal contact made by going door-to-door.

$watermark-text

Interested participants were recruited into the study by a male bilingual interviewer (MS),

who obtained written informed consent. All interviews relied on an interview guide

approved by the institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco.

Interview questions were initially developed from previous studies of Latino immigrant and

low-income populations conceptions of oral disease and experiences with the oral health

care system3, 5, 6, 810 and in consultation with a team of specialists in Latino childrens oral

health. The interview guide had previously been used to generate systematic and reliable

information from a sample of women living in the same town,29, 32 and was adapted as

necessary to fit the mens situation. Interviews documented these fathers understanding of

oral health, both their own and their childrens. Occasionally the wives added comments, but

generally the interviews were with the men only.

Each interview was conducted in Spanish and digitally recorded, then translated and

transcribed. Text data were analyzed using QSR Internationals NVivo 1.1 software

package (QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia). Following standard qualitative

analytic procedures, three independent researchers engaged in a series of iterative readings

of the text while applying codes. A short list of initial codes based on our study questions

were applied first, and subsequent codes developed and applied as they emerged while rereading the transcripts.33, 34 Codes were used to identify recurrent themes expressed by the

fathers. These themes, illustrated by typical quotes from the men, are presented and

discussed in this paper.

$watermark-text

Results

Sample

The sample included 20 immigrant men, 15 of whom had origins in Mexico, while the other

5 came from El Salvador. Their average age was 386.4 years; and they had spent a mean of

156.9 years in the U.S. These fathers report having a low level of educational achievement,

a mean of 5.51.6 years of schooling, and being employed in farmwork, either as fieldhands

or as truckers delivering produce from farm to distributor. The men presently head families

that are primarily low-income, with an average annual income at or below federal poverty

level ($US24,000). Almost one-third (30%) of these parents and most (89%) of their

children had health insurance, mainly public insurance through the federal Medicaid

program. The participating families had an average of 3.31.8 children each, with 65

children total. The mean age of the youngest child per family was 32.1 years.

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 December 20.

Swan et al.

Page 4

Fathers knowledge base as context for this study

In general, fathers assigned much less value to dental health when compared to the overall

health of the body. The fathers interviewed had very limited knowledge regarding basic oral

hygiene concepts and the etiology of dental disease. This lack of knowledge underlies their

scant involvement in their childrens oral hygiene practices, and partially explains why the

fathers accept so little responsibility for this aspect of their childrens health. Also, they

struggled greatly to define what a cavity is, what it looks like, and the significance of such

a condition.

$watermark-text

The fathers assigned much greater importance to general health (ie visiting a physician) than

to dental health (visiting a dentist), a thought illustrated by this father of four young

children:

I see teeth problems as something that affects you, but its not like a problem with

your body, like, for example, pneumonia or a cough, when you have to be caring

for your child. Your teeth may hurt for a little while and you can put up with it for a

day or twoI think a toothache is very different from a cough, a cold, or an

infection. [MCG011]

Similar thoughts were shared by various fathers, suggesting a generalized lack of

understanding of dental conditions and the possible repercussions of neglecting diseased

teeth. Problems in the mouth were seen as being isolated from conditions of the body. Teeth

were described as being functional, yet replaceable:

$watermark-text

Dental health is important, but you can eat without teeth. You can get a bridge.

But if something in your body is damaged, its very difficult to replace it.

[MCG03]

And to another father, his wifes complete lack of molars was of little concern:

She [wife] has never been [to the dentist] because she has never had any problems.

She doesnt have any molars. [MCG08]

$watermark-text

These fathers generally had more interaction with the family physician than with the family

dentist. While several fathers recounted visits with a primary care provider, very few could

remember any direct interaction with a dentist, further verifying that less value is accorded

to oral health. However, they do assign importance to teeth, especially their childrens. Nine

of thirteen who responded to a direct question declared their childrens teeth to be much

more important than their own.

The fathers harbored many misconceptions about the etiology, appearance, and significance

of dental caries. Only one father correctly identified the role of bacteria in caries etiology.

The majority of the fathers, however, had great trouble giving a definition and usually cited

food getting stuck on the teeth and a lack of oral hygiene as the main causes. When asked

what does a cavity look like? or how do you know when your child has a cavity?, the

responses were many and varied. The most common indicator of caries given was stains

[brown, yellow, black] on the teeth, which they also related to black dots on the teeth. To

many of the fathers, however, having a cavity was different than having tooth decay,

with the former preceding the latter. This father described his understanding of the process:

With decay you see black dots, and then you see a hole and it starts to hurtWith

a cavity, the tooth isnt decayed yet. I think its part of the process. When you have

the black dots, if you poke it with something, it becomes a dent on the tooth. Thats

a sign that the tooth is very damageda cavity is just the start of that. Black dots

form when the tooth has decayed already [MCG011].

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 December 20.

Swan et al.

Page 5

Four fathers cited gingival bleeding as the principal sign that their child had cavities.

Another eight fathers reported yellowing of teeth near the gumline and redness of the

gums as principal indicators of cavities, mistaking plaque accumulation and periodontal

irritation for cavity formation. Finally, one father cited bad breath as the principal indicator.

When asked if cavities could threaten the general health of their children, the majority

concluded that cavities affect a childs ability to eat, thus affecting their overall health.

However, only three fathers made reference to the risk of infectious spread from a carious

tooth.

Responsibility for overseeing childrens oral health

$watermark-text

In response to the question who is responsible for taking care of your childrens teeth?

fathers almost unanimously (18 of 19) agreed that their wives mainly performed this task.

Most men indicated that they did occasionally help out, too; only one man denied any

involvement at all in his childrens oral health activities.

The most common reason men provided for the mother being primarily responsible for their

childrens oral health was because the mother did not work and was at home all day with the

children. Therefore, she was available for taking care of the daily tasks that concerned the

children. During the interviews, men reported that a fathers responsibility is to work to

provide for the familys material needs, a thought illustrated by these two fathers:

Well, I could say that it was my wife because she is the one that is at home with

them. I go to work in the morning and I get home at night. [MCG03]

$watermark-text

shes with the children more. I work. I leave home early and when I get home I

am tired. [MCG07]

The fathers expressed complete support for the daily care activities and treatment decisions

made for their children by their wives. Some men reported that on occasion they and their

wives discussed how much they could afford to pay for oral health care for a specific

problem, or to devise a timetable for when needed treatment could be undertaken. Generally,

however, men affirmed their wives actions and took little direct action with respect to their

childrens oral health.

$watermark-text

A major and important exception stemmed from the fact that most of their wives did not

drive. Therefore, the fathers themselves many times drove their children to and from dental

appointments, especially when this involved trips to pediatric specialists located some 70

miles away.29 On such occasions, a father would accompany his wife and child into the

dental office and participate first-hand in decision-making and discussion with the health

professional.

Despite the mens generalized lack of participation in supervising their childrens oral

health, the fathers were very aware of oral health needs and of the dental treatments their

children had undergone. In response to questions such as tell me about your childrens

teeth, and how have their [childrens] experiences with dentists been? these fathers were

able to discuss the condition of their childrens teeth. Of the19 fathers whose children had

past dental treatments, 17 talked in detail about those treatments. Reasons for visiting the

dentist, the childs experience of going to the dentist for the first time, and even which

specific teeth were worked on were all subjects about which the fathers elaborated.

This father, for example, talked about his childs broken tooth and the way he and his wife

deliberated about whether to visit the dentist or not:

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 December 20.

Swan et al.

Page 6

R: That's the problem he has at the moment. His tooth is broken. He had gotten fillings in

some of his molars before. It seems that one of them is opening up again.

I: So, what are you going to do? Do you plan to take him in to get it fixed?

R: Well, a bit later, yes. We [indicating he and his wife] are just seeing if it's going to fall

out. We're waiting to see what they [dentist] recommend, to see what we can do; if we

should just wait for it to fall out or what. [MCG07]

Another father recalled specific details about his sons experience with a local pediatric

dentist:

$watermark-text

I: Where did you take him when you took him to the dentist?

R: I took him to a specialist for children. That specialist only treats children up to five

years of age.

I: Here in [name of rural town]?

R: In Fresno [large city some distance away]. He [the dentist] took some molars out, he put

in some crowns and he put some without metal in the frontthere were about six teeth that

were fixed. [MCG01]

A third father recounted how many fillings his son had received at his last dental visit:

$watermark-text

R: Well, we were taking our son tothe clinic. He had to get some fillings. I think that the

reason was because he eats a lot of candy.

I: He eats a lot of candy?

R: Yes, and he got caries and all that.

I: How many fillings did he get?

R: I think they [dentist] said they were going to do 10, but in the end they only did 8.

[MCG05]

$watermark-text

When to Initiate Home Oral Hygiene Practices

These Latino fathers generally agreed that a child should begin oral hygiene practices at a

young age. When asked to specify more exactly what age, men responded with a wide range

from approximately 6 months of age to 4 years. However, the average age of tooth brushing

initiation that these men reported was 20.99 years. This is much later than the age

recommended by the American Dental Association (ADA), which encourages tooth

brushing upon eruption of the first baby tooth.35

Of the 18 fathers who responded to this question, 10 recommended oral hygiene initiation

after age 2. The major reason being given for this was that all baby teeth should be allowed

to erupt before beginning to brush, as this man noted:

I: at what age should a child start to look after his own teeth?

R: I think that once all their teeth have come in, then they should start looking after

them, according to what I believe. [MCG015]

A second father agreed with this assessment, saying:

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 December 20.

Swan et al.

Page 7

I: At what age should you starting caring for their [childrens] teeth?

R: I suppose that it should be from the time when a parent sees that all their teeth have

come out and formed. Thats when you should start taking care of them. [MCG01]

Another reason given for a later start was that children should begin to brush their teeth only

when they are going to school and have learned to do it properly:

R: Only when you see that they are already going to schoolthats when you start to tell

them [to brush their teeth]. [MCG08]

$watermark-text

Hygiene Assistance Given to Children

When asked, at what age can your child take care of his/her teeth on their own, without

adult supervision? the average age reported by these fathers was 4.12.3 years, with a

range of 110 years. These responses veer from the ADA recommendation, which advises

parents to assist with their childrens brushing until age 6 or 7.36

Actual physical assistance given to children during their home oral hygiene practices

appeared to be very limited, and if given at all, was given almost exclusively by the mothers.

The frequency and degree of such help appears to be minimal though: ten fathers described

the mothers participation as being given sometimes, two men said their wives assisted the

children once in a while, and one man stated twice a week. Only 1 man denied that his

children received any assistance at all:

$watermark-text

I: Do you or your wife supervise them?

R: No.

I: Neither?

R: No. They brush their own teeth and thats it. [MCG06]

Many of the fathers reported that their wives assisted their children with oral hygiene, but

the amount of help given depended entirely on the childs age. Much more help was given to

children aged 2 years and younger, as 9 fathers reported help for this age group. Assistance

was commonly provided at bath time by the mother, often with a finger brush:

$watermark-text

My wife brushes my daughters [2 years old] teeth with a finger brush and she

cleans them. [MCG05]

Every time she bathes him [1 year old], she brushes them. She uses a toothbrush

that you put on your finger. She brushes them. [MCG03]

On the other hand, only 3 fathers reported hygiene assistance given to their children older

than 2 years. One father did report help given to his six year-old:

He [6 year-old son] brushes them, but when we see he hasnt done it well, we do

it. If he doesnt brush them well, she [mother] does it for him. [MCG09]

Generally, though, the fathers reported no assistance was given to their school-aged

children. Fathers assigned great significance to oral hygiene instruction given to their

children at school. For many parents, their children learning to brush at school related to the

age at which they stopped giving assistance. The following 3 quotations demonstrate this:

[I help]very rarelyLike I said, they teach them at school too. They [children]

know how to brush their teeth well. [MCG03]

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 December 20.

Swan et al.

Page 8

The 4 year old also does it himself because they taught him how to do it at

school. [MCG012]

I: Up to what age did you help them? (with tooth brushing)

R: Until they were 4 years old and then at that point they started going to school. They

taught them there too. [wife of MCG018]

$watermark-text

The concept of parental supervision within these families appears to vary widely among

the fathers. They clearly recognized their childrens need for help in regards to oral hygiene,

and some fathers connected the idea of supervision with direct participation in their

childrens oral hygiene practices. Many fathers (11 out of 20), however, directly associated

supervision of their childrens oral hygiene routines with giving their children a verbal

reminder. In lieu of actual demonstration, example of brushing, or physical aid, fathers

believed that simply telling their children to brush adequately fulfilled this parental

responsibility. This father, for example, connected supervision with verbal reminder,

reporting that his children were supervised every time they brush their teeth:

I: Of all the times they brush their teeth, how many of those times are they supervised?

R: All of the times.

I: Always?

$watermark-text

R: Yes, always. In the morning, she [Mother] tells them and they brush their teeth. They go

in one by one and thats how they brush their teeth. [MCG09]

And here a father describes the supervision of his 1 year-old sons brushing:

I: What do you do to look after your childrens teeth?

R: With this small one, she [Mother] tells him, in the evening, to brush his teethhe grabs

his toothbrush and cleans them himself. [MCG017]

While many fathers agreed that some form of parental supervision is important, the most

prevalent idea of to supervise comprised to remind. Monitoring a childs oral hygiene

techniques or habits for effectiveness of brushing was rarely if ever performed:

$watermark-text

I think it is important that they are supervised, but I rarely do thatshe [Mother]

does it more. She tells them to brush their teeth, but she doesnt ask them to open

their mouth afterwards to check. She just tells them to brush their teeth and thats

it. [MCG011]

Fathers clearly associated telling their children to brush with fulfillment of parental

responsibility, even if no other instruction or help was given:

A child cant automatically know how to look after his teeth. Were there to

constantly tell him to brush his teeth. [MCG015]

Seven fathers recognized that simply telling their children to brush their teeth was not

always an effective preventive measure. This thought is illustrated here:

R: We sometimes watch them or tell them how to brush their teeth, that they should brush

them 3 times per day. We tell them, before going to school.that they have to brush their

teeth.

I: So you tell them to do that, but do they always do it?

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 December 20.

Swan et al.

Page 9

R: No, in truth, no. Not always. [MCG07]

Discussion

$watermark-text

This paper contributes to an understanding of how rural Latino fathers understand the

etiology of childrens dental caries and how they view their responsibility for their

childrens oral health. Clearly, the mother is the primary caregiver in these Latino families,

especially with respect to childrens oral health practices. This is consistent with a wide

literature reporting that Hispanic mothers are the main caregivers to their children and play

the dominant role in terms of health/hygiene.2226 However, it is also clear that these fathers

place great value on their childrens health, including the health of their teeth. The fathers

are very supportive of dental treatments for their children, and in many instances ensure they

stay informed about the specifics of oral health needs and dental treatments received by their

children. This supports findings reported by other scholars (Broder, Reisine) with regard to

African American fathers.27, 28

$watermark-text

While fathers recognize that young children cannot be held fully responsible to remember

and conduct oral hygiene independently, these mens perception of when and how much

assistance is needed is very different from ADA recommendations. Fathers are supportive of

their childrens oral hygiene, but their participation in daily practices is minimal. While the

main oversight of oral hygiene is conducted by mothers, they are generally merely

reminding children to brush their teeth, and rarely physically assisting children, even those

as young as 1 year old. Parental supervision of childrens brushing should be explored in

greater detail, as it appears that for these Latino parents to supervise is understood to mean

remind and it is not perceived as necessary to physically assist or visually check a childs

teeth. This is particularly true once a child attends school and is known to have received oral

hygiene instruction in the classroom. Fathers place great value on school-provided hygiene

instruction and for many, the age at which their children started school was the age at which

they were assumed to be able to brush effectively by themselves.

$watermark-text

These families are initiating oral hygiene routines later than the age recommended by the

ADA (upon eruption of first tooth). While there exists a wide age range for toothbrushing

initiation (6 months to 4 years), the fathers do place value on caring for baby teeth. As

reported in other work on Latino parents, fathers do not recognize the early signs of caries,

not connecting discolored teeth with decay, nor do they understand its etiology.32. Fathers,

though not directly involved in their childrens oral hygiene practices, stay aware of dental

topics through conversations with their wives and other associates. Therefore, programs that

aim to improve the health of rural Latino children, while ideally aimed at both parents,

should especially continue to focus on mothers, with the realization that the information will

indeed disseminate to the fathers indirectly.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include having a small convenience sample, social desirability and

recall biases, and a single rural location. The interviewer expected reticence from the fathers

and supposed that this would be a potential limitation of the study. However, quite the

opposite proved to be true. Mostly likely because of gender concordance between

interviewer and interviewee, the fathers were very easily approached and openly shared their

experiences. In instances when the men provided socially undesirable answers, they would

often follow their comments with why should I lie to you? This congenial transparency

made the interview process very enjoyable.

Despite its limitations, this study expands the present literature in important ways. It is the

first to contribute knowledge about what Latino fathers know and do with respect to their

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 December 20.

Swan et al.

Page 10

childrens oral hygiene. As such, it forms a basis for the development of future research

aimed at uncovering in greater detail the role of Latino immigrant fathers in providing for

their childrens oral health needs.

$watermark-text

Further exploration is critical if we hope to improve the oral health of this population. Upon

comparing this studys results with those of other, larger studies conducted principally with

women,29, 32 it is clear that rural Latino men and women have unique explanatory models

for how dental disease develops and sometimes interpret symptoms differently. Thus, while

most studies investigate womens views and actions and present them as parental views,

studies should also include men who have distinct patterns of thought and behavior. Fathers

are pivotal in the decision-making process, and many times are key facilitators of a dental

visit by being able to drive the children to their appointments. Thus, their opinions are

significant and their input is relevant. In order to include this set of parents in research,

studies may want to focus on finding these fathers at home in the evenings, on weekends,

and at other times, and to employ male bilingual interviewers.

Conclusions

The following conclusions can be drawn based on this studys findings:

$watermark-text

1.

Rural Latino fathers place value on taking care of childrens teeth at a young age.

2.

While rural Latino fathers may not actively participate in their childrens oral

hygiene, they are aware of what takes place both at home and with dental

professionals.

3.

They are supportive of dental treatments for their children, financially and

otherwise.

4.

Many times, supervision of childrens oral hygiene signifies only a verbal

reminder to brush teeth. Children are brushing independently, starting as young as

one year old.

5.

In many families, oral hygiene routines are initiated later than the age

recommended by the ADA (upon eruption of first tooth).

6.

To improve rural Latino childrens health, programs must focus on both parents but

especially on mothers. Educational messages aimed at women will disseminate to

fathers, indirectly.

$watermark-text

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grant number U54 DE 014251

(Center to Address Disparities in Childrens Oral Health) and CTST grant number T32 DE017249. All authors have

made substantive contribution to this study and/or manuscript, and all have reviewed the final paper prior to its

submission. We would like to also thank Erin Masterson for her helpful comments.

References

1. [Accessed February 20, 2009] Pew Hispanic Center/Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation 2002

National Survey of Latinos Survey Briefs. Latinos in California, Texas, New York, Florida and

New Jersey. 2004. Available at: http://pewhispanic.org/reports/report.php?ReportID=15.

2. Lukes SM, Miller FY. Oral health issues among migrant farmworkers. J Dent Hyg. 2002; 76(2):

134140. [PubMed: 12078577]

3. Woolfolk MP, Sgan-Cohen H, Bagramian R, Gunn SM. Self-reported health behavior and dental

knowledge of a migrant worker population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1985; 13(3):140

142. [PubMed: 3860333]

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 December 20.

Swan et al.

Page 11

$watermark-text

$watermark-text

$watermark-text

4. United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), National Institute of Dental and

Craniofacial Research (U.S.). Rockville, Md: U.S. Public Health Service Dept. of Health and

Human Services; 2000. Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General.

5. Nurko C, Aponte-Merced L, Bradley EL, Fox L. Dental caries prevalence and dental health care of

Mexican-American workers children. J Dent Child. 1998; 65(1):6572.

6. Woolfolk M, Hamard M, Bagramian RA, Sgan-Cohen H. Oral health of children of migrant farm

workers in northwest Michigan. J Public Health Dent. 1984; 44(3):101105. [PubMed: 6592350]

7. Quandt SA, Clark HM, Rao P, Arcury TA. Oral health of children and adults in Latino migrant and

seasonal farmworker families. J Immigr Minor Health. 2007; 9(3):229235. [PubMed: 17252193]

8. Lukes SM, Simon B. Dental services for migrant and seasonal farmworkers in US community/

migrant health centers. J Rural Health. 2006; 22(3):269272. [PubMed: 16824174]

9. Entwistle BA, Swanson TM. Dental needs and perceptions of adult Hispanic migrant farmworkers

in Colorado. J Dent Hyg. 1989; 63(6):286292. [PubMed: 2630614]

10. Hilton IV, Stephen S, Barker JC, Weintraub JA. Cultural factors and children's oral health care: a

qualitative study of carers of young children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007; 35(6):429

438. [PubMed: 18039284]

11. Watson MR, Horowitz AM, Garcia I, Canto MT. Caries conditions among 25-year-old immigrant

Latino children related to parents' oral health knowledge, opinions and practices. Community Dent

Oral Epidemiol. 1999; 27(1):815. [PubMed: 10086921]

12. Adair PM, Pine CM, Burnside G, Nicoll AD, Gillett A, Anwar S, et al. Familial and cultural

perceptions and beliefs of oral hygiene and dietary practices among ethnically and socioeconomically diverse groups. Community Dent Health. 2004; 21(1 Suppl):102111. [PubMed:

15072479]

13. Domoto P, Weinstein P, Leroux B, Koday M, Ogura S, Iatridi-Roberson I. White spots caries in

Mexican-American toddlers and parental preference for various strategies. J Dent Child. 1994;

61(56):342346.

14. Mikhail BI. Hispanic mothers' beliefs and practices regarding selected children's health problems.

West J Nurs Res. 1994; 16(6):623638. [PubMed: 7839680]

15. Watson MR, Horowitz AM, Garcia I, Canto MT. Caries conditions among 25-year-old immigrant

Latino children related to parents' oral health knowledge, opinions and practices. Community Dent

Oral Epidemiol. 1999; 27(1):815. [PubMed: 10086921]

16. Weinstein P, Domoto P, Wohlers K, Koday M. Mexican-American parents with children at risk for

baby bottle tooth decay: pilot study at a migrant farmworkers clinic. J Dent Child. 1992; 59(5):

376383.

17. Hoeft KS, Barker JC, Masterson EE. Mexican-American caregivers initiation and understanding

of home oral hygiene for young children. Pediatr Dent. 2009 in press.

18. Zambrana, R., editor. Understanding Latino families: scholarship, policy, and practice. London:

Sage Publications; 1995.

19. Marin, G.; Marin, B. Research with Hispanic populations. New York: Sage Publications; 1991. p.

42-55.

20. Saracho O, Spodek B. Challenging the stereotypes of Mexican American Families. Early Child

Educ J. 2007; 35:223231.

21. Mirande, A. Hombres y Machos: masculinity and Latino culture. Boulder, CO: Westview Press;

1997.

22. Cabrera, N.; Garcia Coll, C. Latino Fathers: Uncharted Territory in Need of Much Exploration. In:

Lamb, ME., editor. The role of the father in child development. 4th ed.. New York: Wiley; 2004.

p. 98-120.

23. Coltrane S, Parke R, Adams M. Complexity of involvement in low-income Mexican American

families. Fam Relations. 53(2):179189.

24. Pleck, JH.; Masciadrelli, BP. Paternal involvement: levels, sources, and consequences. In: Lamb,

ME., editor. The role of the father in child development. 4th ed.. New York: Wiley; 2004. p.

222-271.

25. Coltrane S. Research on household labor: modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of

routine family work. J Marriage Fam. 2000; 62:12081233.

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 December 20.

Swan et al.

Page 12

$watermark-text

26. Barajas M. Beyond home-host dichotomies: a comparative examination of gender relations in a

transnational Mexican community. Socio Persp. 2007; 50(3):367392.

27. Broder H, Reisine S, Johnson R. Role of African-American fathers in child-rearing and oral health

practices in an inner-city environment-a brief communication. J Public Health Dent. 2006; 66(2):

138143. [PubMed: 16711634]

28. Reisine S, Ajrouch, Sohn W, Lim S, Ismail A. Characteristics of African-American male

caregivers in a study of oral health in Detroit-a brief communication. J Public Health Dent. 2009 epub Jan 15, 2009.

29. Barker JC, Horton S. An ethnographic study of rural Latino childrens oral health: intersections

among individual, community, provider and regulatory sectors. BMC Oral Health. 2008 e-pub

March 31, 2008.

30. Galanti G. The Hispanic Family and Male-Female Relationships: An Overview. J Transcult Nurs.

2003; 14(3):180185. [PubMed: 12861920]

31. Tamez E. Familism, machismo, and child rearing practices among Mexican Americans. J

Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1981; 19(9):2125. [PubMed: 6916808]

32. Horton S, Barker JC. Rural Latino immigrant caregivers conceptions of their childrens oral

disease. J Public Health Dent. 2008; 68:2229. [PubMed: 18248338]

33. Bernard, HR. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. 4th ed..

Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press; 2005.

34. Miles, MB.; Huberman, AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed..

Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994.

35. American Dental Association. Available at: http://www.ada.org/public/topics/baby.asp.

36. ADA. Available at: http://ada.org/prof/resources/pubs/jada/patient/patient_11.pdf.

$watermark-text

$watermark-text

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 December 20.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Report 2Document13 pagesReport 2api-3711225No ratings yet

- English XIIDocument12 pagesEnglish XIIdanielNo ratings yet

- Molecules - 1 (Carbs & Lipids) V2Document13 pagesMolecules - 1 (Carbs & Lipids) V2ormattNo ratings yet

- What Explains The Directionality of Flow in Health Care? Patients, Health Workers and Managerial Practices?Document7 pagesWhat Explains The Directionality of Flow in Health Care? Patients, Health Workers and Managerial Practices?Dancan OnyangoNo ratings yet

- Antifertility DrugsDocument12 pagesAntifertility DrugsforplancessNo ratings yet

- Immunoparasitology and Fungal ImmunityDocument31 pagesImmunoparasitology and Fungal ImmunityShakti PatelNo ratings yet

- Principles of Routine Exodontia 2Document55 pagesPrinciples of Routine Exodontia 2رضوان سهم الموايدNo ratings yet

- Product Support Booklet: Lara Briden Endometriosis and PcosDocument24 pagesProduct Support Booklet: Lara Briden Endometriosis and PcosVeronica TestaNo ratings yet

- Premio 20 DTDocument35 pagesPremio 20 DThyakueNo ratings yet

- Treatment in Dental Practice of The Patient Receiving Anticoagulation Therapy PDFDocument7 pagesTreatment in Dental Practice of The Patient Receiving Anticoagulation Therapy PDFJorge AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Datasheet Reagent SansureDocument3 pagesDatasheet Reagent Sansuredanang setiawanNo ratings yet

- SECOND Semester, AY 2022-2023: Mission VisionDocument34 pagesSECOND Semester, AY 2022-2023: Mission Visionjeyyy BonesssNo ratings yet

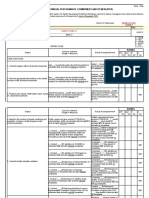

- Individual Performance Commitment and Review (Ipcr) : Name of Employee: Approved By: Date Date FiledDocument12 pagesIndividual Performance Commitment and Review (Ipcr) : Name of Employee: Approved By: Date Date FiledTiffanny Diane Agbayani RuedasNo ratings yet

- Bleak House - Book ThreeDocument36 pagesBleak House - Book ThreeNicklaus Adam Rhodes100% (1)

- Cardiology UQU 2022Document29 pagesCardiology UQU 2022Elyas MehdarNo ratings yet

- Clinical Findings and Management of PertussisDocument10 pagesClinical Findings and Management of PertussisAGUS DE COLSANo ratings yet

- Otzi ARTEFACTSDocument15 pagesOtzi ARTEFACTSBupe Bareki KulelwaNo ratings yet

- Prevmed Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesPrevmed Reaction Paperapi-3801039100% (5)

- Trauma Sellick's ManoeuvreDocument4 pagesTrauma Sellick's ManoeuvrevincesumergidoNo ratings yet

- TAPSE AgainDocument8 pagesTAPSE Againomotola ajayiNo ratings yet

- Cotton Varieties HybridsDocument15 pagesCotton Varieties HybridsAjay KumarNo ratings yet

- Makabuhay IpDocument7 pagesMakabuhay IpButterflyCalmNo ratings yet

- LAB 4 - StreptococcusDocument31 pagesLAB 4 - Streptococcussajad abasNo ratings yet

- Eucalyptus Oil PDFDocument2 pagesEucalyptus Oil PDFJenniferNo ratings yet

- Sterilization of Water Using Bleaching PowderDocument15 pagesSterilization of Water Using Bleaching PowderSupriyaNo ratings yet

- Heparin - ClinicalKeyDocument85 pagesHeparin - ClinicalKeydayannaNo ratings yet

- Aioh Position Paper DPM jdk2gdDocument26 pagesAioh Position Paper DPM jdk2gdRichardNo ratings yet

- Adrenal Function Urine TestDocument30 pagesAdrenal Function Urine TestDamarys ReyesNo ratings yet

- ADHD and More - Olympic Gold Medalist Michael Phelps and ADHDDocument6 pagesADHD and More - Olympic Gold Medalist Michael Phelps and ADHDsamir249No ratings yet

- SterilizationDocument6 pagesSterilizationIndranath ChakrabortyNo ratings yet