Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Indias Green Industrial Policy

Uploaded by

maharazaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Indias Green Industrial Policy

Uploaded by

maharazaCopyright:

Available Formats

COMMENTARY

Indias Green Industrial Policy

Pursuing Clean Energy for Green Growth

Ashwini K Swain

Keeping with the global trend,

India seems to be executing a

Green Industrial Policy that

seeks to prioritise production and

consumption of clean energy.

Will it lead to green growth and

sustainable development?

The views expressed are personal.

Ashwini K Swain (ashwini@ashwiniswain.net)

is at the CUTS Institute for Regulation and

Competition, New Delhi.

Economic & Political Weekly

EPW

MARCH 1, 2014

he current global financial crisis

demands swift action by governments to support, restructure and

sustain industrial activities. Simultaneously, addressing the global climate

change requires significant modifications in industrial incentives and regulations. Both the events have forced the

state to bring industrial policy back to

the core of policy agenda. Consequently,

the new industrial policy called green

industrial policy (GIP) seeks to make

industrial growth green, inclusive and

economically dynamic.

GIP, seeking to develop new industries

and adopt new technologies, involves essential policy changes. It is different

vol xlix no 9

from conventional industrial policy in

two ways: first, it requires different policy

instruments; second, it involves stronger

state engagement in markets. Under GIP,

states seek to promote sustainable patterns of production and consumption by

pricing resource consumption and promoting efficient technologies through

market transformation.

There is a global upsurge in adoption

of GIP by both developed and developing

states. The underlying rationale for its

adoption is to create globally competitive domestic firms, while it promises a

range of spin-off developmental and environmental benefits. Considering the

fact that energy is a major input for industrial process and major contributor

to industrial emissions, GIP seeks to

tame energy consumption and hasten

the development of low-carbon alternatives to fossil fuels. Will the alleged GIP,

with its emphasis on clean energy production and consumption, lead to green

growth and sustainable development?

19

COMMENTARY

Bundling Policies and Interests

Keeping with the global trend, India

seems to be pursuing the GIP, particularly since the past decade. India is not

only a major emerging economy with

high industrial growth prospects, but also

a major consumer of energy resources.

Consequently, production and use of clean

energy have rightly been prioritised in

Indias GIP for achieving the goals of

green growth and sustainable development. India has been promoting renewable energy (RE) as an alternative to

fossil fuels to meet rising industrial

energy demand, and energy efficiency

(EE) measures to tame the demand.

The country has set a target to raise its

RE capacity to 74 gigawatts (GW) by

2022, including 22 GW of solar capacity.

With a renewable installed capacity of

27.7 GW (13% of total installed capacity),

the country is already a global leader.

Over the Twelfth Five-Year Plan period

(2012-17), it aims to install 30 GW of renewable capacities with a federal outlay

of around $4 billion. The country has

certainly set an ambitious target for RE

development. The private sector has a

strong role to play in executing the plan;

in fact, much of RE development so far

has taken place with the private sector.

Nearly one-third of the planned investment in infrastructure sectors over the

Twelfth Five-Year Plan period has been

earmarked for the electricity sector; about

half of this investment is sought from the

private sector. The state has been engaged

in setting up a favourable policy environment, with complementary policies, regulatory interventions, incentive mechanisms

and research and development (R&D)

support, to facilitate RE development.

While wind constitutes a large share

(about 70%) of Indias existing RE installed

capacity, considering the potential of solar

energy, the country has developed a

strategy to tap it. A national mission the

Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission (JNNSM) has been set up to facilitate

solar energy development to achieve

the target of 20 GW grid-connected and

2 GW off-grid solar capacities by 2022.

The state has made several policies to

mandate and incentivise RE production

at national and sub-national levels. Renewable Purchase Obligation (RPO) is a key

20

policy to create demand for RE. Each

sub-national electricity regulatory commission has set a specific RPO for the

utilities in their respective states. The

national target was set at 5% for the

financial year 2009-10 and was to be

increased by 1% each year for the next

10 years, with the aim to procure 15% of

consumable electricity from RE sources

by 2020. The policy also makes a provision for solar-specific RPO set at 0.25%

in 2012, to be raised to 3% by 2022.

The Renewable Energy Certificate (REC)

programme is being implemented to

penalise the utilities that fail to meet

their RPO; they have to compensate by

purchasing equivalent RECs (Charnoz

and Swain 2012).

To encourage private sector engagement, the state has made provisions for

capital subsidy and interest subsidy for

setting up RE production units. RE generators have the choice to trade electricity

at a preferential tariff or to trade RECs

separately after selling the electricity at

a competitive tariff. In addition, the state

is providing tax benefits to both generators and manufacturers on import of RE

technology (e g, solar panels) and additional support on R&D. Simultaneously,

the state has enforced local content requirement (LCR) raised to 75% in the

second phase of the JNNSM to promote

growth in domestic manufacturing.

India has an equally ambitious target

for EE, with a target to save 10 GW by

2014-15 and, thus, avoid 19 GW of additional generation capacity. The National

Mission on Enhanced Energy Efficiency

(NMEEE) has been set up to facilitate

the process with mandatory provisions

and incentive mechanisms. The perform,

achieve and trade scheme targets energyintensive industries, which account for

60% of Indias total primary energy consumption, and are required to meet a

certain level of EE in a specified time

period. Those who achieve EE gains

beyond their target are rewarded with

energy saving certificates (ESCerts); those

who fail to meet their target can buy

ESCerts to make up the difference, or

pay a penalty (ibid).

With the launch of the scheme last

year, India has become the first developing country to adopt market-based

mechanisms to trade EE. Simultaneously,

the state is using market transformation

strategy to promote production and use

of energy efficient appliances in designated sectors. While manufacturers are

being incentivised to manufacture superefficient appliances, products are being

labelled to raise consumer awareness

and demand (Swain 2013). The Standards and Labelling Programme being

implemented seeks to raise consumer

awareness and demand for energy efficient

equipment. The Super-Efficient Equipment Programme is a rebate programme

that incentivises leading manufacturers

to produce super-efficient equipment on

a large scale and market them at a competitive price. Both the programmes,

implemented by the Bureau of Energy

Efficiency, aim to hasten energy conservation while giving a boost to the manufacturing industry.

The Indian approach seeks to ensure

domestic energy security and dynamic

industrial growth catering to domestic

developmental needs, while accruing

mitigation co-benefits to address the

global call for climate action. Unlike in

the past, when the state retained control

over the market, under the GIP, the state

seeks to actively engage with the market

by creating a favourable policy environment. Realising the limitation of state

capacity to implement the strategy, the

state is seeking to build non-state (market)

players and offer incentives to hasten

the process (Harrison and Kostka 2012).

An initial high capital subsidy to generators and enforcement of LCR to kick-start

the solar industry, and setting-up a market

for energy service companies are two

good examples.

The Way Forward

Indias GIP holds good promises for

green growth and sustainable development. Achieving the JNNSM target will

result in mitigation of 95 million tonnes

(Mte) of CO2e annually by 2022. Simultaneously, NMEEE has potential to achieve

mitigation of 98 Mte of CO2e annually.

While promoting dynamic clean energy

industries, GIP is expected to reduce carbon

intensity of Indian industries. Clean energybased industrial growth is expected

to be inclusive by promoting regional

MARCH 1, 2014

vol xlix no 9

EPW

Economic & Political Weekly

COMMENTARY

development, employment generation and

improved energy access.

Though India has ambitious targets,

and the right policies and incentives in

place, it is too early to make any judgment on the outcome. Yet, two fundamental challenges weigh upon Indias

GIP, viz, finance gap and lack of market

transparency. While access to private

finance is crucial for development of the

clean energy industry, current interest

rates remain too high and financing

institutions remain reluctant to invest. A

comprehensive financing strategy optimising various funding sources is a key

prerequisite for scaling-up the clean energy industry. Prevailing lack of market

transparency in the sector may result in

rent-seeking and market distortion. A

study by the Centre for Science and

Environment reveals how a major conglomerate has subverted rules to acquire

a stake in the JNNSM much larger than

Economic & Political Weekly

EPW

MARCH 1, 2014

allowed legally (Bhushan and Hamberg

2012). The state needs to provide realtime, credible and usable information

that the public can trust and use to hold

it and private actors accountable. Simultaneously, the state needs to strengthen

the monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to ensure that rules and norms are

not disrupted.

Addressing these challenges, which

are not insurmountable, will largely depend on state-business relations, private

sector capacity, bundling of interests and

policies, and creative manoeuvres taken

by the state. Much depends on the extent

to which the private sector shares the

state goals, and the way they are organised

and their capacity for collective action.

At the same time, the state needs to build

the confidence that private activities will

be supported not frustrated and rentseeking will be avoided. The process will

shape, and be shaped by, state-business

vol xlix no 9

relations and build new forms of developmental coalitions. Since the policies

are not self-implementing, independent

electricity regulators would emerge as

key facilitators (or blockers). The regulators have key roles to play in implementing these policies and would affect

the pace and pattern of transition. If

successful, India could lay out a path

for green growth in other developing

countries too.

References

Bhushan, C and J Hamberg (2012): The Truth about

Solar Mission, Down to Earth, 15 February.

Charnoz, O and A Swain (2012): High Returns,

Low Attention, Slow Implementation: The Policy Paradoxes of Indias Clean Energy Development, AFD Working Paper 125, July, Agence

Franaise de Dveloppement, Paris.

Harrison, T and G Kostka (2012): Manoeuvres for

a Low Carbon State: The Local Politics of Climate Change in China and India, DLP Research Paper 22, June, Developmental Leadership Programme.

Swain, A (2013): Taking Energy Efficiency to the

Market, Business Standard, 7 March.

21

You might also like

- Bally's Chicago Casino Agreement ExhibitsDocument147 pagesBally's Chicago Casino Agreement ExhibitsCrainsChicagoBusinessNo ratings yet

- Webquest For NapoleonDocument5 pagesWebquest For Napoleonapi-208815387No ratings yet

- White PaperDocument13 pagesWhite Paperasaditya109No ratings yet

- MNRE Annual Report 2019-20Document192 pagesMNRE Annual Report 2019-204u.nandaNo ratings yet

- Mnre PDFDocument171 pagesMnre PDFPadhu PadmaNo ratings yet

- Solar Allocation SoarsDocument2 pagesSolar Allocation SoarsshubhammsmecciiNo ratings yet

- Industry AnalysisDocument15 pagesIndustry AnalysisRajagopalan GanesanNo ratings yet

- How Has Make in India' Been A Boost To The Renewable Energy Sector?Document2 pagesHow Has Make in India' Been A Boost To The Renewable Energy Sector?Patrick BowmanNo ratings yet

- Anurag Atre 5Document70 pagesAnurag Atre 5Kshitij TareNo ratings yet

- Energy Storage LawDocument17 pagesEnergy Storage LawKushal MishraNo ratings yet

- Electric Vehicles.Document12 pagesElectric Vehicles.Shubhra KediaNo ratings yet

- Potential, Growth and Policies Related To Renewable GrowthDocument4 pagesPotential, Growth and Policies Related To Renewable GrowthSaurabh SinghNo ratings yet

- Renewable Energy For Sustainable Development in India SeminarDocument5 pagesRenewable Energy For Sustainable Development in India SeminarKiran KumarNo ratings yet

- Investment Opportunities in Renewable Energy in IndiaDocument19 pagesInvestment Opportunities in Renewable Energy in Indiampratap1No ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument3 pagesIntroductionsweetshk910No ratings yet

- Exploring SDG 7 Through An Indian LensDocument14 pagesExploring SDG 7 Through An Indian LensEunha MinNo ratings yet

- Project On Industrial Analysis: Energy Sector: BY: Abhishek Kumar Sinha Kumari Priya Shreel Dwivedi Anwesha ChatterjeeDocument12 pagesProject On Industrial Analysis: Energy Sector: BY: Abhishek Kumar Sinha Kumari Priya Shreel Dwivedi Anwesha ChatterjeesibbipriyaNo ratings yet

- Government of India Policy Towards Green Economy and Sustainable DevelopmentDocument4 pagesGovernment of India Policy Towards Green Economy and Sustainable DevelopmentNehal SharmaNo ratings yet

- CHP and District Cooling: An Assessment of Market and Policy Potential in IndiaDocument12 pagesCHP and District Cooling: An Assessment of Market and Policy Potential in IndiamgewaliNo ratings yet

- Vibrant Gujarat: Presented byDocument39 pagesVibrant Gujarat: Presented byAnkit ShuklaNo ratings yet

- ANES Assignment: Renewable Energy Policies in IndiaDocument5 pagesANES Assignment: Renewable Energy Policies in Indiaxenom2No ratings yet

- Case Study: Renew Power: Group 4Document12 pagesCase Study: Renew Power: Group 4Nandish GuptaNo ratings yet

- 9th Research-PaperDocument10 pages9th Research-Papertanveerheir68No ratings yet

- Renewable Energy Sector Funding: Analysis and Report by Resurgent India February 2015Document36 pagesRenewable Energy Sector Funding: Analysis and Report by Resurgent India February 2015Student ProjectsNo ratings yet

- Cover StoryDocument8 pagesCover StoryBhavesh SwamiNo ratings yet

- Current Affairs 2010 WWW - UpscportalDocument141 pagesCurrent Affairs 2010 WWW - UpscportalMayoof MajidNo ratings yet

- Economic Analysis of Renewable Energy SectorDocument13 pagesEconomic Analysis of Renewable Energy SectorN SethNo ratings yet

- Uttar Pradesh Green Hydrogen Police 2022Document12 pagesUttar Pradesh Green Hydrogen Police 2022SRINIVASAN TNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Analysis On The Indian Renewable Energy Sector."feb 3,2012)Document3 pagesComprehensive Analysis On The Indian Renewable Energy Sector."feb 3,2012)solo_gauravNo ratings yet

- Renewable Energy Status PDFDocument178 pagesRenewable Energy Status PDFwasif karimNo ratings yet

- Greening of MSMEs in IndiaDocument7 pagesGreening of MSMEs in IndiaTanu AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Renewable Energy Convention June 4-5, 2014Document13 pagesRenewable Energy Convention June 4-5, 2014Rdy SimangunsongNo ratings yet

- BERT Unit 5Document10 pagesBERT Unit 5SivaNo ratings yet

- Energy Policy: R. Srikanth TDocument12 pagesEnergy Policy: R. Srikanth TAbhishek kumar100% (1)

- ILS GROUP-3 PresentationDocument6 pagesILS GROUP-3 PresentationMadhan Kumar SNo ratings yet

- June 2020: Team InfraeyeDocument10 pagesJune 2020: Team InfraeyedestinationsunilNo ratings yet

- Climate Change and Sustainable Development-Shubham KaliaDocument7 pagesClimate Change and Sustainable Development-Shubham KaliaShubham KaliaNo ratings yet

- Jan 2022Document66 pagesJan 2022Rudra ChinmayeeNo ratings yet

- India's Ambitious Renewable Energy TargetsDocument281 pagesIndia's Ambitious Renewable Energy TargetssreenivasNo ratings yet

- Powering India: The Road To 2017Document13 pagesPowering India: The Road To 2017Rajnish SinghNo ratings yet

- Policy Measures - Industry Sector 5.1. Critique A. Energy Efficiency and Conservation in The Textile and Steel Sector IndustriesDocument14 pagesPolicy Measures - Industry Sector 5.1. Critique A. Energy Efficiency and Conservation in The Textile and Steel Sector IndustriesSathea NuthNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Consumption and Production (SCP) : Role of Green Product To Promote SCP in IndiaDocument5 pagesSustainable Consumption and Production (SCP) : Role of Green Product To Promote SCP in IndiaSuman MandalNo ratings yet

- 1.introduction of Power and EnenrgyDocument10 pages1.introduction of Power and EnenrgyRamdas BochareNo ratings yet

- Cover StoryDocument7 pagesCover StoryBhavesh SwamiNo ratings yet

- Abstract For Conference - IcareDocument2 pagesAbstract For Conference - IcareMukul JoshiNo ratings yet

- Falling Short An Evaluation of The Indian Renewable Certificate MarketDocument22 pagesFalling Short An Evaluation of The Indian Renewable Certificate MarketnishantNo ratings yet

- Utility Policy-62f10c923356bDocument16 pagesUtility Policy-62f10c923356bavanishNo ratings yet

- Economics Project Report A2Document14 pagesEconomics Project Report A2N SethNo ratings yet

- New Renewable Energy in India: Harnessing The Potential: Export-Import Bank of IndiaDocument175 pagesNew Renewable Energy in India: Harnessing The Potential: Export-Import Bank of Indiakittu99887No ratings yet

- Salient Features of The Integrated Energy Policy of India Are As FollowsDocument3 pagesSalient Features of The Integrated Energy Policy of India Are As Followsdhanusiya balamuruganNo ratings yet

- 933 Gnull BJ21048 Sec A Group 6 MPIT Assignment 2Document9 pages933 Gnull BJ21048 Sec A Group 6 MPIT Assignment 2AryanNo ratings yet

- UCSD Input To CSO VNR 2020 Rejoinder - A Clean Energy Agenda For Uganda June 17 2020Document2 pagesUCSD Input To CSO VNR 2020 Rejoinder - A Clean Energy Agenda For Uganda June 17 2020Kimbowa RichardNo ratings yet

- Regulating The Race To Renewables: PoliciesDocument4 pagesRegulating The Race To Renewables: PoliciesSanjayMeenaNo ratings yet

- Bagasse Based CogenerationDocument13 pagesBagasse Based CogenerationknsaravanaNo ratings yet

- BCML II EnclosuresDocument46 pagesBCML II Enclosurespradeepika04No ratings yet

- IndiaDocument7 pagesIndiaSamit PaulNo ratings yet

- Korea's Green Growth Strategy - Implications On Business Fields: Case of Secondary Battery - (Based On Samsung SDI)Document15 pagesKorea's Green Growth Strategy - Implications On Business Fields: Case of Secondary Battery - (Based On Samsung SDI)Eric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Hitachi Energy Annual-Report 2022-23 Web-VersionDocument212 pagesHitachi Energy Annual-Report 2022-23 Web-VersionMan MohanNo ratings yet

- NDCs in 2020: Advancing renewables in the power sector and beyondFrom EverandNDCs in 2020: Advancing renewables in the power sector and beyondNo ratings yet

- 2021 Energy Policy of the Asian Development Bank: Supporting Low-Carbon Transition in Asia and the PacificFrom Everand2021 Energy Policy of the Asian Development Bank: Supporting Low-Carbon Transition in Asia and the PacificNo ratings yet

- Carbon Pricing for Energy Transition and DecarbonizationFrom EverandCarbon Pricing for Energy Transition and DecarbonizationNo ratings yet

- Ipcr Staff NewDocument6 pagesIpcr Staff NewMeynard MagsinoNo ratings yet

- Information Handbook Refer To Chapter II Section 4.1b of DTCPDocument49 pagesInformation Handbook Refer To Chapter II Section 4.1b of DTCPV Kumar0% (1)

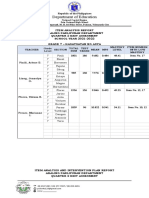

- Item Analysis Repost Sy2022Document4 pagesItem Analysis Repost Sy2022mjeduriaNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument11 pagesMultiple Choice QuestionsAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Radware C-Suite Report FinalDocument19 pagesRadware C-Suite Report FinalVijendra RawatNo ratings yet

- The Smithsonian's African American Museum - A Monument To Respectability Politics - Culture - The GuardianDocument8 pagesThe Smithsonian's African American Museum - A Monument To Respectability Politics - Culture - The GuardianFernanda_Pitta_5021No ratings yet

- SJ-20150112110821-003-ZXR10 2900E Series (V2.05.12) Easy-Maintenance Secure Switch Alarm Handling - 651690Document276 pagesSJ-20150112110821-003-ZXR10 2900E Series (V2.05.12) Easy-Maintenance Secure Switch Alarm Handling - 651690Yuniar Mita RuswandiNo ratings yet

- IODC Crystal C3 250M EUR PGLDocument10 pagesIODC Crystal C3 250M EUR PGLcajoe1000No ratings yet

- Public Notice 17 of 2021 Return Submission Payment Due 10 March 2021Document3 pagesPublic Notice 17 of 2021 Return Submission Payment Due 10 March 2021Josphat FunaniNo ratings yet

- 3 Tarrosa Vs SingsonDocument3 pages3 Tarrosa Vs Singsonchristopher d. balubayanNo ratings yet

- Company Law SummerisedDocument15 pagesCompany Law SummerisedOkori PaulNo ratings yet

- Composition of Fund Clusters: Codes Description Fund Clust Er Existing Uacs Funding SourceDocument15 pagesComposition of Fund Clusters: Codes Description Fund Clust Er Existing Uacs Funding SourceKelvin CaldinoNo ratings yet

- Tinglayan (4) PinukpukDocument3 pagesTinglayan (4) PinukpukLyka FrancessNo ratings yet

- Wise Deposit Note 662136227 1003987913 enDocument2 pagesWise Deposit Note 662136227 1003987913 encavNo ratings yet

- Organizational Factors: The Role of Ethical Culture and RelationshipsDocument15 pagesOrganizational Factors: The Role of Ethical Culture and RelationshipsAlice AungNo ratings yet

- Financial Management Principles and Applications 12th Edition Titman Test BankDocument36 pagesFinancial Management Principles and Applications 12th Edition Titman Test Bankabsorbentbollv6a2c100% (22)

- Lcat VawcDocument20 pagesLcat VawcMikshiNo ratings yet

- P.L Trading CorporationDocument5 pagesP.L Trading CorporationNhậtNo ratings yet

- TXMAS Honeywell ListDocument64 pagesTXMAS Honeywell ListLorena Yepes VareloNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Internal Revenue TaxesDocument11 pagesModule 1 Internal Revenue TaxesSophia De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- PlaintDocument31 pagesPlaintHarneet Kaur100% (1)

- RWDSU Constitution - 2018Document31 pagesRWDSU Constitution - 2018LaborUnionNews.comNo ratings yet

- Report Showcase Brgy Assembly 2nd Sem 2019Document6 pagesReport Showcase Brgy Assembly 2nd Sem 2019PRINCE LLOYD D.. DEPALUBOSNo ratings yet

- New Dem ACA Letter To Congressional LeadershipDocument4 pagesNew Dem ACA Letter To Congressional LeadershipSahil KapurNo ratings yet

- Legaltech SurveyDocument5 pagesLegaltech SurveyJohnNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 2Document6 pagesLesson Plan 2Victoria DonghiNo ratings yet

- The Rights To ProtectionDocument10 pagesThe Rights To ProtectionKaren Julieth SANABRIA CARILLONo ratings yet

- Flow Over Weirs Apparatus: Model FM 02Document22 pagesFlow Over Weirs Apparatus: Model FM 02Mayuresh ChavanNo ratings yet