Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Herodotus's Account of The Battle of Salamis

Uploaded by

pagolargoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Herodotus's Account of The Battle of Salamis

Uploaded by

pagolargoCopyright:

Available Formats

Herodotus's Account of the Battle of Salamis

Author(s): Benj. Ide Wheeler

Source: Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 33 (1902),

pp. 127-138

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/282591 .

Accessed: 03/01/2015 09:07

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 190.189.27.66 on Sat, 3 Jan 2015 09:07:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vol.xxxiii.] Herodotus's Accountof Battle of Salamis.

VIII.

I27

Herodotus's Account of the Battle of Salamis.

BY PRESIDENT BENJ. IDE

UNIVERSITY

WHEELER,

OF CALIFORNIA.

OUR chief sources of knowledlgeconcerningthe battle of

Salamis are Aeschylus,Persians, 345 ff.,and Herodotus VIII,

70-95. Of only secondary value-possibly, as some have

thought,of no independentvalue-are Diodorus (Ephorus)

VIII, 17, 2-19, 2, and Plutarch in the Thcmistocles.1The

vulgate account, basing upon Herodotus, and placing the

battle inside the straits,was firstseriouslycalled in question

by Loeschke, Ja/rb.f: P/il. 1877, pp. 25 ff. Finding Aeschylus and Herodotus in discord, he prefersto follow the

former,who was an eye-witness,and prepares an account of

the battle which he believes to be supported by the statements of Aeschyius and in harmonywith those of Diodorus.

He makes no attemptto lharmonizethe statementsof Herodotus, except to suggest a correctionof the text at the point

of most serious discrepancy. The battle he believes to have

occurredoutside the narrowsmade by the point of Cynosura

and the opposite headland of Attica. His main points are

the following:

(i) It is not crediblethatthe Persian ships the nightbefore

the battle could have entered the straits 2000 metres distant

fromthe Greeks withoutbeing observed by them.

(2) Psyttaleia was evidentlyexpected by Xerxes to be in

the midst of the impendingbattle,E'Vyadp8&)wrpdp Tr)q PavC'E70

vI?

7/ ,?EXXovO-s? 6'aEa-Oat E''O

qos (Herod.VIII, 76);

AaXt,qai,

hence the disembarkationof troopsthere. If the battlewere

fought inside the sound, it would be too far away to be

sought as a refugeby the Greeks (cf. Aesch. 450 ff.).

(3) Aeschylus confirmsDiodorus when he indicates (Pers.

366-68) that one detachmentof ships was sent around the

southof Salamis to block the northwestpassage, and the rest

l Cf. Perrin, B., Plutarch's Themis/oclesazn.] Ar4is/ides; note pp. 206 ff.

This content downloaded from 190.189.27.66 on Sat, 3 Jan 2015 09:07:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I28

Benj. Ide Wheeler.

[I902

in three ranks were set to guard the straitat Psyttaleia. If

the Greeks were surrounded by a movement of Persian

ships inside the straits,there were no need of this outside

manoeuvre.

(4) The Persians are representedby Aeschylus as having

heard the Greeks,theirpaean, the trumpetblast, the stroke

of the oars, before they saw them. This can only be explained on suppositionthat Cynosura intervened. The Persians in question were thereforeat the southwest passage

between Psyttaleiaand Cynosura. The Greeks became visible as theybent around the point of Psyttaleia. Hence the

rightwing was seen first.

(5) The Ezva-revw'(Aesch. 4I3) refersto thenarrowsbetween

Cynosura and Attica. The turningpoint of the battle was

the confusioninto whichthe Persians fell when forcingtheir

way into this strait.

(6) The statementof Hlerod.VIII, 85 that the Phoenicians

occupied in the Persian line the wing towardEleusis and the

west, and the Ionians that "toward the east and Peiraieus"

is from Loeschke's point of view unintelligible. It yields

be substituted

meaning for him, however,if only EaXap4zvos,

for 'EXEuo-'YoW,so that the Phoenicians be assigned the wing

towardSalamis and the west.

Loeschke, therefore,arranges both lines across the straits

fromshore to shore,- fromeast to west.

solutionis attemptedby W. W. GoodA somewhatdifferent

win in Vol. I, Papers Amer. Schloo, pp. 239 ff. Starting

with an acceptance of Loeschke's criticism of the vulgate

theory,he joins with him in thinkingit incredible that the

Persians should have taken up their position,on the night

beforethe battle,withinthe straits. He does not, however,

follow Loeschke in amending the text of Herodotus, but

rather seeks to harmonize Herodotus's account with the

others by a differentinterpretationof the vexed passage

Herod. VIII, 85. He seeks, namely,to locate the struggle

withinthe straits,but makes the Persians enter in the morning, and ascribes their defeat to the fact that they were

attacked before they had formedtheirline, and beforethey

This content downloaded from 190.189.27.66 on Sat, 3 Jan 2015 09:07:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vol. xxxiii.]

Herodotus's Account of Battle of Salamis.

129

had recovered fromthe confusion incident to passing the

narrows.

His main points,additionalto those of Loeschke, are:

(i)

"A.eschylus beyond doubt representsthe Persians as

enterin1g

thestraitsafterdaybreak." So Diodorus and Plutarch.

(2)

"Their line (called by Aeschylus pE'/,ua)fell into some

confusionin enteringthe narrows; and theyneversucceeded

met by

in regainingtheirorderof battle,being immedliately

the Greeks as they passed the long point of Salamis."

(3) "SThere is nothing inconsistentwith this view of the

battle except the common interpretationof two passages of

Herodotus": the firstof these, VIII, 76, which represents

"the Persians as bringing up their west wing to Salamis

KCVKXOv,uLevot

during the nighitbefore tfe battle," he explains as

referringto the sending of ships around the south of the

island to close the northwestpassage (cf. Diod. XI, I 7; Plut.,

I2);

and the second passage, VIII, 85, he explains

Themnist.

by applying the points of the compass to the order of the

Persian line as it entered the straits,i.e. it entered end on

with the rightwing leading, so that the rightwing thus lay

to the west or northwest. The Greeks are made to take a

position at firstacross the sound, between Magoula and the

Perama (correspondingto Diodorus's statement), i.e. south

to north,and then, by advancing their right wing first,to

assume a position southeast to northwestsufficientto bring

them near to the desired line, i.e. withtheirleftwing slightly

west of north.

Professor Goodwin's statement gives a clear, consistent

story of the battle, and has the merit of establishing an

apparentlycomplete reconciliationbetween the accounts of

Herodotus and Aeschylus. It is, however,ratheran attempt

at reconciling with the Aeschylean account two conflicting passages in Herodotus than any attempt at reconciling

the two accounts taken as a whole. To Aeschylus, as

an eye-witness,must be given undoubtedlythe preference

in case of ultimate conflict. We submit,however,that the

account of Herodotus must be interpretedas a whole. It

can scarcely be doubted that Herodotus, who certainly

This content downloaded from 190.189.27.66 on Sat, 3 Jan 2015 09:07:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

130

Bcnj. Ide Wleeler.

[I902

visited the scene of the battle within thirty-fiveyears

after its occurrence,must have had when he wrote a selfwhether that plan

consistent plan of the battle in nmind,

was rightor wrong. We believe that a reviewof Herodotus's

account as a whole will show that the two passacges cited

above are not the only ones which appear to be inconsistent

with the plan suggested by ProfessorGoodwin; we believe

that it will also appear that he misunderstandsAeschylus.

The essential featuresof Herodotus's account may be discussed in the chronologicalorderas he gives them.

In the forenoonof the day beforethe battle the Persian

(i)

ships were beached at Phaleron, and the leaders were in

council. So soon as it was decided to give battle,the ships

T v laXapva

were pushed off and headed for Salamis, 'rVb

(? 70), just as the land troops were at niohtfallbeaded c'rb

In

i7V HfEXO7rOlVJJ7cTvO.Contrast 7rpoS Tr7V YaXaaitva,? 75.

the open sea off Peiraieus the ships were sorted out and

arrangedKaT' ?'o-vXtyv.As nightwas, however,approaching,

it was foundnecessaryto postpone battle untilthe next day.

At nightthe Persian armybroke camp and startedalong the

shore toward the Peloponnesus. Hence it was in the midst

of his army,already on its slow march,that Xerxes had his

QV

(Lo apzrt'ov1aXa/.t,Voq (? 90).

seat the next morning vT7ro\ ope

The whole Attic shore was Persian.

(2) The Greeks, especially the Peloponnesians,seeing how

completelytheywould be isolated in case of a naval defeat,

were in great perturbation,and the withdrawalof the Peloponnesian contingent,or perhaps even of the whole fleet,to

the Isthmuswas all but determinedupon. Themistocles sent

Sikinnos to warnXerxes of the proposedmovement. Xerxes

believed. The storywas probableenough,forit seemed surely

the wise course forthe Greeks to pursue. Why should they

at great risk of completeisolationof the armystay to defend

a countryalreadylost ? Xerxes acted promptly. His purpose

was to preventthe withdrawalof the Greek fleet.

v-cv llpp-e'av

First, lhe immediatelydisembarked7roXXo)t0v

upon the island of Psyttaleia,thus securingwith troops this

slhore,as he had already the Attic shore. This marks the

This content downloaded from 190.189.27.66 on Sat, 3 Jan 2015 09:07:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vol. xxxiii.] Herodotus's Accountof Ba/tle of Salamis.

I3I

proposed line of his battle. Ancient naval battles were by

preference,as Duncker (Gesch. d. Altert.)has shown, fought

from shore to shore, i.e. from friendlyshores respectively,

the

and not with the wings reposing,the one upon a friendly,

otherupon an unfriendly,

shore. The Greeks wereat Salamis

and held the island, and if, as seems a priori natural, the

Persians were proposingin general to make the Attic shore

theirbackground,Psyttaleiawould be at the end of theirleft

and, as lying in the face of the strait,could well be viewed as

/LeXXovT7)9 eOco-Oat(? 76), and as

CE 77oppo TI' vavuaX7,9qT

affordinga finevantage point fromwhich to succor friends

or hew down foes according as the refugeesfromeitherside

mightseek it.

The second part of Xerxes's movementtook place at night

and concerned the fleet. It consisted of two distinct manoeuvres (

-ie

Be

Firstly,az'vq2yov/ezy ro&'a -pr'Epuv idKpaq1cvKov/LEvO1w7rpoq

r\vIaXaFitva; secondly,a'4yov &e ot a,uO\r\vKe'ovreK

Ic r

Kvvo'o-ovpav TeTay/LJevot,

xaTer%ov

T'fl?

ToZ 7Vop9f,loP

VXVCr.

Te /1%pI MouvVX611

adzrza

Concerningthe firstof these manoeuvres,two difficulties

face the interpreter:(a) Which is the west wing? (b) Was

the movement one around the south of the island or inside

the sound ?

ProfessorGoodwin's interpretationmakes Herodotus use

" west wing" in ? 85 of the rig-ht

wing and in ? 76 of the left

wing,and this in a connected account of the samc battle.

Regarding the wings as named by their tenporaryposition,

he naturallyis forced by the specificationthat the other or

eastern wing was at,a,u T7L Ke'o0 TE Kxa T 7P Kvvo'o-ovpavto

locate the west wing out along the shore of the island,though

no possible ratio forleading the fleet over there can be discovered. Dr. Lolling (Meerenge zvonSalamis, Aufsdtze an

Curtizus

gewidinet)attemptsto solve the diifficulty

by reading

Leros forKeos. This is impossible,not only forgrammatical

reasons (viz. the use of -re ca\,and the necessityof making-e

balance LeLP,

while 8e introduces a parentheticalclause), but

forthe plain reason that if the Persian ships were already at

This content downloaded from 190.189.27.66 on Sat, 3 Jan 2015 09:07:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

132

Benj. Ide Wheeler.

[I902

Leros, the Greeks were already surrounded,and there was

no need of doing anything further(cf. Hauvette, Herod.,

p.

4I2).

The whole difficulty

finds a readysolution when we take

into account that we are dealing here with a continuous,

consistent,and well-consideredaccount in which the Persian

fleetis always spoken of in termsof the Attic shore against

which it was located on the day before the battle, before

which it was drawn up on the day of the battle,and which

was regarded as its permanent"point of departure." Precisely the same thingis done in ? 85, where,if I may anticipate somewhat,it will be shown that the wings are again

named in terms of the trend of the Attic shore. The 7pos

&'7repDsIcdpa9is throughoutthe rig/twing.

The movementdescribed by Herodotus as KvKXoVF,EJVot

7rpo

T\)v 2aXa/uva is by some understood as within the sound

toward a position by the Perama, by others as a circumnavigation of the island. No one gives a propervalue to KVKXOV,/evot. If, now, this movementconsisted in sending-a part

of the righlitwing around the island, KVKXOv,)ueVoL

is the per-

fectlynaturaldescriptionof the movementwhich sends this

detachment of the rightwing-around behind the left wing.

It seems to me probable that such a detachmentwas sent

reasons

around the island, and forthe followinig

(a) Aesch. Pers. v. 368, aXXa9 8\ Ac6KXa v-ooV A1tavroq

7rwpt(rTdat) seems to referto such a movement; if not, it

refersto somethingotherwiseunmentionedin our sources.

(b) DiodoruLsXI, 17 says: He sent out the naval force of

the Egyptianswithordersto close the straitbetween Salamis

and the land of Megara. The same is implied by Plutarch.

Two hundcredis just the number of ships assigned by

HerodotLusto the Egyptians. For this see Goodwin,p. 248.

The Egyptians would naturallybelong in the rightwingwith

the Phoenicians.

(c) The enemy's ships,which Herodotus reportsAristeides

as having seen in his passage fromAegina, may well have

belonged to this detachment. See Goodwin,p. 251.

(d) The objections which have been raised on the score

This content downloaded from 190.189.27.66 on Sat, 3 Jan 2015 09:07:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vol.xxxiii.] Herodotus's Accountof Batle of Salamis.

I33

of the distance and the darkness of the night are not of

weight. The weather,as usual in September,was probably

calm; the triremeswere moved by oars and were swift; the

distance was not such as to require over fouror five hours;

i.e. the triremeswould reach the straitsbeforedaybreak.

(e) The movementwas an exact parallel to that of sending

two hundredships around Euboea with the design of shutting

up the Greeks in the Euripus.

(f) The flightof the CorinthianAdeimantus throughthe

sound to the west may be a base libel, but the veryintroduction of the storyshows that Herodotus did not think of a

Persian fleetas posted offSt. George. The second manoeuvre

of the fleetconsisted in bringingthe leftwing-over to enter

and occupy the strait. In consonance with his general way

of viewingthe plan of battle, Herodotus here also expresses

this occu'pationin termsof the Attic coast,-" occupied clear

down to Munychia all the strait with the ships." The

temptationto justifyan oracle cited later undoubtedlyaided

in dictating the choice of word. If these ships had been

already lying offthe straits,as is shown by a',u4l Tr7)vK6ov TE

ecatTrRvKvvo'oovpav, something,new must have happened,somethingradicallynew. The theoryof ProfessorGoodwin

really leaves nothingto be done. That Herodotus believed

the ships occupied the straits inside and were posted along

the shore facing the bay of Ambelaki, we think certainly

proven by what follows. If he did not thinkthey did something of this sort,why should he specificallyadd, "They did

this in silence, that those on the otherside might not know

of it"? (? 76). It is, indeed, only by what I must think a

misinterpretationof Aeschylus (Pers. 382) that Professor

Goodwin refuses to think that the Persians began entering

the straits before daylight. Aeschylus says (1. 38X): they

sail offeach to his appointed station,and (11.382-3) all the

nightkeep sailing throughi

until(11.384-5), when the nightis

passed, no place is left for the Greeks to sail out. The

- tcac9to-raro

antithesisof &tdw7Xoov

eca9io-raoavand 'cX7rXovv

is too apparent; the word-play(tcaOt(o-aro) points it out; note

also 7rXe'ov-t- ad7rXoov- e'c7rXovv. Professor Goodwin's

This content downloaded from 190.189.27.66 on Sat, 3 Jan 2015 09:07:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I34

Beej. Ide Wheeler.

[1902

interpretationof 1. 382 is given on p. 246, "the Persian ships

are kept rowing about all night." Aside from the common

meaningof the language and the implicationof the antithesis,

therearises the consideration: how were theysailing to their

appointed stationsby "rowing about all night"? The interpretationof thispassage is not, however,of primeimportance

to us, -to ProfessorGoodwin and his theoryit is of fatal

importance. Loeschke and Goodwin lay great stress upon

the impossibilityof effectingsuch a movementin the face of

theirattention. Goodwinin the

the enemywithoutattractingr

firstplace is surelymistakenin assertinc,thatit was a moonlit

night. The statementof Aesch. v. 365 is against this,and

Busolt, Gr. Gesc.2 (II, 702, note 2), shows that at the time

of the battle the moon must have been well advanced in its

last quarterand probablydid not rise beforeabout two o'clock.

The Greeks were deep back in the bay of Ambelaki some

four miles from the opposite Attic coast. That there was

doubtless danger of attractingthe attentionof the Greeks is

shown by the fact that the Persians moved in silence, but

that it was possibleto do it under cover of the darkness must

be undoubted. That the south passage, i.e. that between

Cynosuraand Psyttaleia,was not entirelyblockedis suggested

by the arrivalof the Aeginetan triremethe next morning.

Herodotus's account turns now in ? 78 to the Greeks.

They were busy in discussion. "They did not know yet

that the barbarianswere surroundingthemwith their ships,

but supposed them to be in the same positions as they saw

themby daylight." Accordingto ProfessorGoodwin'stheory,

they would be, except for the ships sent around the island.

Then follows the arrival of Aristeides,l from whom as an

" eye-witness" Themistocles firstlearns that the Persians

have moved as he desired.

Not until Aristeides's reportis confirmedby the Tenian

deserters do the Greek leaders really believe they are surrounded. Once convinced,they directlyprepare for battle.

1 Aristeidesmayhave landed on the southshoreofCynosura,

whencea fiveor

ten minutes'walk overthe ridgewould have taken him to the Greek camp,or

he mayhave roundedthe point.

This content downloaded from 190.189.27.66 on Sat, 3 Jan 2015 09:07:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vol. xxxiii.]

Herodotus's Account of Battle of Salzamis.

I35

The dawn is breaking,. The men are assembled to hear some

words of exhortation. They hurry to their places on the

ships. The triremewiththe blessing of the Aeacidae arrives.

They push off. Hardly are theyoffwhen the barbariansare

upon them. At firstthe Greeks recoil,and some were just

beaching their boats again, but Ameinias on the leftpushes

ahead, joins fight,and the rest follow. The fightbegins off

the mouth of the bay of Ambelaki. Mr. Goodwin's plan

makes it begin at the other side or the middle of the sound,

before the Persians have reached their position and formed

their line. The Greeks, according to his plan, would have

been obliged to back water at at least i miles beforebeaching. In ? 89 Herodotus says Greeks whose ships were lost

swam ashore. If the Greek line had been across the sound,

this were unlikely. Near those of the leftwing would have

been a hostile shore. Most of the otherscould have reached

shore only by swimmingby and around manyfriendlyships.

Passing to the details of the battle, H-erodotus,? 85, makes

the statement: "Opposite the Athenians had been arranged

the Phoenicians,for they held the wing toward Eleusis and

the west; opposite the Spartans the Ionians; they had the

wing toward the east and Peiraieus." As we have already

seen, this statementhas given rise to abundant controversy,

but yet it is just the statementthat it was most naturalfor

Herodotus in accordance with his entire conception of the

plan of battleto make. He viewedthe Persian line as arrayed

before the Attic coast. This coast opposite the mouth of

the bay of Ambelaki lies exactlyeast and west. Herodotus

had not studied out the battle on a map, but on the spot.

It was of slight matter that the map shows Eleusis to be to

the northwest. The plain fact is that the shore runs east

and west, and the west end of the sound opens toward

Eleusis, the east end toward Peiraieus. A fleet arrayed

along this shore has thereforeits rightwing toward the west

and Eleusis, its lefttowardthe east and Peiraieus.

The storyof the battle,aside fromthe personal incidents,

is brief. The Greeks preservedtheirorder,but the Persians,

as they crowded down to fall upon the Greeks in their nar-

This content downloaded from 190.189.27.66 on Sat, 3 Jan 2015 09:07:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I36

Beny. Ide Whecler.

[1902

rowerposition,interfered

witheach other,rakingone another's

oars, and making themselvesan easy prey. The position of

the Greeks forced the Persians into narrowerquarters, cz'

crTsC, so Aeschylus puts it. The result could not have been

different,

as Herodotus says. The ancient naval battle was

a ramming match. A fully equipped triremecarried only

eighteen fightingmen to I70 oarsmen. The great consideration was speed, and the abilityto drivethe ioo feetlong barge

against the enemy's ship and disable it. Once the Persians

were crowded upon each other,the battle was settled. This

was the reason why the Greeks kept the shelter of their

narrow bay. It is inconceivable that they should, as Mr.

Goodwin would have them, leave the shelter of a friendly

shore,and lean theirleftwing upon a hostileshore.

The confusionof the Persians was increased by the ambition of those in the rear lines (Aesch. says theywere drawn

up three deep) to make a good showingunder the eye of the

king wlhosat on the shore behind them. The Phoenicians

were drivenback by theAthenians(e 7'v rypv

Plutarchsays),

and Herodotus tells of their coming up to rnake a certain

complaintto the king. The flightbecame general. All the

ships pushed for the north passage. Here the Aeginetans,

who had moved forwardfrom their position on the right

Greek wingrat the tip of Cynosura,were waiting for tlhem,

and taking them in the flank made havoc of the fug-itives,

earningthemselvesthe chiefgloryof the day.

This is Herodotus's perfectlyintelligibleand self-consistent

account. From it it seems to us clear that he thoughtof the

Persians as already drawn up at daybreak along the Attic

shore and closing the north passage of the strait,so as to

extend from Psyttaleia on the Attic shore opposite it to a

point westwardtherefromopposite the northerncape bounding Ambelaki bay. This makes a line of 21 miles, or if

extended to the Perama, of 4 miles. The Persian fleet,after

the withdrawalof the 200 Egyptian ships, could not have

exceeded 6oo ships. Aeschylus says these were drawn up

three deep. This allows, on the basis of a 21-mile extent

of line, 65 feet waterwayfor each ship, considerablymore

This content downloaded from 190.189.27.66 on Sat, 3 Jan 2015 09:07:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vol.xxxiii.] HIerodotus'sAccountof Battle of Salamis.

I37

than was necessary to operate it, being more than double the

width covered by ship and oars. The Greek fleet of about

300 ships, probablydrawn up in double line, had frompoint

to point(east and west) of Ambelaki bay a space of i- nmiles,

affording 50 feet per vessel. The whole sea-room was

IO,OOO,OOOsquare metres,or reckoningIOOO

ships, IO,OOO

square metres per ship.

It is chieflyin deferenceto certainstatementsof Aeschylus

that Loeschke and Goodwin have constructedtheir theories

of the battle. These theories are in certain and unreconcilable conflictwith Herodotus. They are too inherently

improbable. Loeschke locates the battleat the southpassage,

which is narrowand brokenby an island and by shoals. Not

to fiftyships could have passed it abreast.

over thirty-five

He is chieflyinfluencedin selecting this position by belief

that Aeschylus's statement that the Greeks were not seen

till the last momentrequiredthem to be hidden by Cynosura.

This implies that the Greeks entered battle by a complete

wheeling of their line, whichwould not only be difficult,

but

would expose the flank. It would furthermorebe the left

wing,and not,as Aeschylus says,the right,whichthe Persians

would see first. Goodwin's plan oblig,esthe Persians to enter

battle througha waterway of less than three-quartersof a

mile in width,where not over fiftyto seventy-fivetriremes

could move abreast. Though off the strait all night, and

wide awake, and though a shore held by their own troops

invited their entrance, they are made to await the risk of

daylightto accomplish this dangerous movement. And yet

Herodotus says -ETETXaT7-o.

Two or threepresumedimplicationsof Aeschylus'slanguage

are all that remain of the supposed reasons for positing this

hypothesis,contraryas it is to the entiretyof Herodotus's

account as well as to all good reasons in general. These are:

(a) Aeschylus says that the Greeks suddenly appeared in

view (Pers. 390). When the sun had risen there burst out

fromthe camp of the Greeks the sound of the paean echoed

over the wave from the island cliffs,smiting dismay to the

hearts of the Persian host. For, lo, this blessed note of the

This content downloaded from 190.189.27.66 on Sat, 3 Jan 2015 09:07:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

138

Bcnj. Ide Wlieeler.

[1902

paean was not the song of men who meditated flight,but

rather of men hastening in inspired courage to the battle.

Then the blare of the trumpet set all the air afire, and

straightwaycame the dash and the swish of the oar as it

smote the brine to the boatswain's call. And with a rush

theywere all beforetheireyes.

This fits Herodotus's account. The Greeks tarried in

council till day was dawning. Then came late the decision

to fight. The sailors were addressed just as the sun was

rising. With an enthusiasmtheyare offto theirboats. The

trumpetgives the signal for launching. Suddenly they are

off,and way down in the recesses of the bay fourmiles away,

where just before all had been quiet in the gray of twilight,

the Persianssee thewatercoveredwiththeadvancingtriremes.

(b) The expression p'evi4ais believed by Goodwin to refer

to the columnarorder of the Persians in passing the straits.

The cause of their confusionwhich resulted in their defeat

was, accordingto his view,thatin passing the straits(ev Trev5)

they were obliged to narrowthis column. They were then

attacked before they recovered fromtheir confusion. This

is not what Aeschylus says. He says the reverse. "For

the firstthe stream of the Persian host held on its way, but

when the mass of the ships had been crowded togetherinto

close quarters,they were no help to each other,but rathera

hindranceand destruction,etc.," and then the Greeks smote

them hip and thigh. This crowdingezv 7evjOicomes at the

end, not at the beginning. Compressedinto a narrowerbed,

what had been a steady stream now becomes a confusionof

waters. It is the same thingwhichHerodotus describes. As

they came down upon the Greeks in their narrowerposition

offthe mouthof the bay, theycrowdedtogether,touchedoars,

and were disabled.

Herodotus's account is not only self-consistent; it is in

entireconsistencywith the otheraccounts.

This content downloaded from 190.189.27.66 on Sat, 3 Jan 2015 09:07:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Cambridge University Press, The Classical Association The Classical QuarterlyDocument27 pagesCambridge University Press, The Classical Association The Classical QuarterlyMatías Ezequiel PughNo ratings yet

- West - 2003 - 'The Most Marvellous of All Seas' The Greek EncouDocument17 pagesWest - 2003 - 'The Most Marvellous of All Seas' The Greek EncouphilodemusNo ratings yet

- (LU) ANDERSON, J.K., (1954) - A Topographical and Historical Study of AchaeaDocument22 pages(LU) ANDERSON, J.K., (1954) - A Topographical and Historical Study of AchaeaJulian BrouetNo ratings yet

- American Journal of Philology - 'The Military Situation in Western Asia On The Eve of Cunaxa' by Paul A. Rahe, 1980Document19 pagesAmerican Journal of Philology - 'The Military Situation in Western Asia On The Eve of Cunaxa' by Paul A. Rahe, 1980pbas121No ratings yet

- Vickers, Persepolis, Vitruvius and The Erechtheum Caryatids. The Iconography of MedismDocument27 pagesVickers, Persepolis, Vitruvius and The Erechtheum Caryatids. The Iconography of MedismClaudio CastellettiNo ratings yet

- The Greek Ships at Salamis and The DiekplousDocument6 pagesThe Greek Ships at Salamis and The DiekplousHappy WandererNo ratings yet

- 5-The Lelantine War c700-c540 BCDocument4 pages5-The Lelantine War c700-c540 BCAC16No ratings yet

- Ashton, The Lamian War-Stat Magni Nominis UmbraDocument7 pagesAshton, The Lamian War-Stat Magni Nominis UmbraJulian GallegoNo ratings yet

- Periclean Imperialism Poly LowDocument30 pagesPericlean Imperialism Poly LowFelix QuialaNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument9 pagesThe University of Chicago PressMarcelo LouveirasNo ratings yet

- The Persian ΚαρδακεσDocument16 pagesThe Persian ΚαρδακεσShahenda AnwerNo ratings yet

- North OdisseasDocument18 pagesNorth OdisseasparanormapNo ratings yet

- Herodotus' Catalogues of The Persian Empire in The Light of The Monuments and The Greek Literary Tradition, O. Kimball ArmayorDocument10 pagesHerodotus' Catalogues of The Persian Empire in The Light of The Monuments and The Greek Literary Tradition, O. Kimball ArmayorΕΣΤΙΤΙΣΣΙΩΝΤΙΣΙΣNo ratings yet

- The Battle of Thermopylae Historical/Geological ReportDocument14 pagesThe Battle of Thermopylae Historical/Geological ReportAnonymous taXBIHNo ratings yet

- Edson 1947 TopographyofThermeDocument19 pagesEdson 1947 TopographyofThermerybrybNo ratings yet

- HAMMOND-The Location of Aegae PDFDocument4 pagesHAMMOND-The Location of Aegae PDFtasospapacostasNo ratings yet

- T W C W H: HE Estern Ontribution TO Orld IstoryDocument18 pagesT W C W H: HE Estern Ontribution TO Orld IstoryJustin ElliottNo ratings yet

- Anacharsis the Scythian: A Wise Barbarian in Ancient GreeceDocument7 pagesAnacharsis the Scythian: A Wise Barbarian in Ancient GreeceMarina MarrenNo ratings yet

- Egypt Exploration Society Digitizes Journal Revealing Name of Lake MoerisDocument16 pagesEgypt Exploration Society Digitizes Journal Revealing Name of Lake MoerisMartinaNo ratings yet

- Aristophanes EcclesiazusaeDocument288 pagesAristophanes EcclesiazusaeEmily FaireyNo ratings yet

- Larcher's Notes On Herodotus (1844)Document469 pagesLarcher's Notes On Herodotus (1844)Babilonia CruzNo ratings yet

- Lorimer-The Hoplite Phalanx With Special Reference To The Poems of Archilochus and TyrtaeusDocument66 pagesLorimer-The Hoplite Phalanx With Special Reference To The Poems of Archilochus and TyrtaeusnicasiusNo ratings yet

- [Bowra] Homeric Epithets for Troy 1960 - 628372Document8 pages[Bowra] Homeric Epithets for Troy 1960 - 628372Juan FernandezNo ratings yet

- Bassett 1931 The Place and Date of The First Performance of The Persians of TimotheusDocument14 pagesBassett 1931 The Place and Date of The First Performance of The Persians of TimotheusSly MoonbeastNo ratings yet

- WaceDocument27 pagesWacerboehmrboehmNo ratings yet

- (Pp. 107-167) Sidney Colvin - On Representations of Centaurs in Greek Vase-PaintingDocument65 pages(Pp. 107-167) Sidney Colvin - On Representations of Centaurs in Greek Vase-PaintingpharetimaNo ratings yet

- Kase, Edward W. Mycenaean Roads in Phocis.Document7 pagesKase, Edward W. Mycenaean Roads in Phocis.Yuki AmaterasuNo ratings yet

- Tsade and He Two Problems in The Early History of The Greek Alphabet Phoenician LettersDocument19 pagesTsade and He Two Problems in The Early History of The Greek Alphabet Phoenician LettersgrevsNo ratings yet

- Laconian Opkos in Thucydides V. 77 Author(s) : A. G. Laird Source: Classical Philology, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Jul., 1907), Pp. 337-338 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 25/06/2014 03:01Document3 pagesLaconian Opkos in Thucydides V. 77 Author(s) : A. G. Laird Source: Classical Philology, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Jul., 1907), Pp. 337-338 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 25/06/2014 03:01Gabriela AlmadaNo ratings yet

- SADDINGTON Twon Notes On Roman GermaniaDocument6 pagesSADDINGTON Twon Notes On Roman GermaniaNicolás RussoNo ratings yet

- Franz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteDocument26 pagesFranz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Cleisthenes and AtticaDocument20 pagesCleisthenes and Atticakptandreas100% (1)

- Notices of Books: of The Macedonian Army. Berkeley Etc.: UniverDocument2 pagesNotices of Books: of The Macedonian Army. Berkeley Etc.: UniverRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Dates in Early Greek HistoryDocument18 pagesDates in Early Greek HistorySoner özmenNo ratings yet

- The Classical Review examines Homer's IliadDocument7 pagesThe Classical Review examines Homer's IliadFranchescolly RibeiroNo ratings yet

- How Greeks First Sailed Into Black SeaDocument6 pagesHow Greeks First Sailed Into Black Seaonr100% (1)

- A. B. Bosworth - Arrian and The AlaniDocument40 pagesA. B. Bosworth - Arrian and The AlaniDubravko AladicNo ratings yet

- Barrett, Sohaemus, King of Emesa and SopheneDocument8 pagesBarrett, Sohaemus, King of Emesa and SopheneFranciscoNo ratings yet

- The Athenian Expedition To Melos in 416 B.C.Document35 pagesThe Athenian Expedition To Melos in 416 B.C.tamirasagNo ratings yet

- The First Sacred War: A Political Conflict, Not a Holy WarDocument21 pagesThe First Sacred War: A Political Conflict, Not a Holy WaraguaggentiNo ratings yet

- Perikles Vs Thrace 447 BCDocument6 pagesPerikles Vs Thrace 447 BCmiron isabelaNo ratings yet

- Aeschylus - The Persians, IntroDocument5 pagesAeschylus - The Persians, IntroJohnathan Tyson AndrewsNo ratings yet

- The Dates of Procopius' Works: A Recapitulation of The EvidenceDocument13 pagesThe Dates of Procopius' Works: A Recapitulation of The EvidenceIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- Grated Cheese Fit For HeroesDocument3 pagesGrated Cheese Fit For HeroesGustavo OliveiraNo ratings yet

- The Achaemenid Army in A Near Eastern ContextDocument6 pagesThe Achaemenid Army in A Near Eastern Context626484201No ratings yet

- Themistocles and The Supposed Second Message To Xerxes - The Anatomy of A LegendDocument14 pagesThemistocles and The Supposed Second Message To Xerxes - The Anatomy of A LegendMatheus Moraes MalufNo ratings yet

- CYPRUS in The Achaemenid PeriodDocument16 pagesCYPRUS in The Achaemenid PeriodYuki AmaterasuNo ratings yet

- CASPARI - The Ionian Confederacy PDFDocument17 pagesCASPARI - The Ionian Confederacy PDFwaldisiusNo ratings yet

- Herodoto. New PaulyDocument7 pagesHerodoto. New PaulyNestor ChuecaNo ratings yet

- CHRIMES - 1930 - Herodotus and The Reconstruction of HistoryDocument11 pagesCHRIMES - 1930 - Herodotus and The Reconstruction of HistoryJulián BértolaNo ratings yet

- (Oppian), Cyn. 2,100-158 and The Mythical Past of Apamea-On-The-Orontes-Hollis 1994Document15 pages(Oppian), Cyn. 2,100-158 and The Mythical Past of Apamea-On-The-Orontes-Hollis 1994AnnoNo ratings yet

- (Oppian), Cyn. 2,100-158 and The Mythical Past of Apamea-On-The-Orontes-Hollis 1994Document15 pages(Oppian), Cyn. 2,100-158 and The Mythical Past of Apamea-On-The-Orontes-Hollis 1994AnnoNo ratings yet

- Balcer, Jack Martin - The Liberation of Ionia. 478 B.C. - Historia, 46, 3 - 1997 - 374-377Document5 pagesBalcer, Jack Martin - The Liberation of Ionia. 478 B.C. - Historia, 46, 3 - 1997 - 374-377the gatheringNo ratings yet

- The Bithynian Army in The Hellenistic PeriodDocument18 pagesThe Bithynian Army in The Hellenistic PeriodMarius Jurca67% (3)

- Kantorowicz PDFDocument27 pagesKantorowicz PDFmiaaz13No ratings yet

- DOCUMENT A brief note on the circumcised Odomantes in Aristophanes' comedyDocument4 pagesDOCUMENT A brief note on the circumcised Odomantes in Aristophanes' comedyStefan StaretuNo ratings yet

- OPKIA IN THE ILIAD AND CONSIDERATION OF A RECENT THEORYDocument10 pagesOPKIA IN THE ILIAD AND CONSIDERATION OF A RECENT THEORYAlvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- Roman Penetration Into The Southern Red PDFDocument47 pagesRoman Penetration Into The Southern Red PDFAnonymous KxceunzKsNo ratings yet

- Agesilaus in DiodorusDocument15 pagesAgesilaus in DiodorusDámaris RomeroNo ratings yet

- La Kabylie Et Les Coutumes Kabyles 1/3, Par Hanoteau Et Letourneux, 1893Document607 pagesLa Kabylie Et Les Coutumes Kabyles 1/3, Par Hanoteau Et Letourneux, 1893Tamkaṛḍit - la Bibliothèque amazighe (berbère) internationale100% (3)

- The Historiography of The Activities of Francis DrakeDocument8 pagesThe Historiography of The Activities of Francis DrakepagolargoNo ratings yet

- Raleigh, Hariot, and Atheism in Elizabethan and Early Stuart EnglandDocument10 pagesRaleigh, Hariot, and Atheism in Elizabethan and Early Stuart EnglandpagolargoNo ratings yet

- The Extent of Spartan Territory in The Late Classical and Hellenistic PeriodsDocument25 pagesThe Extent of Spartan Territory in The Late Classical and Hellenistic PeriodspagolargoNo ratings yet

- Constantine VII's Peri Ton StratiotonDocument20 pagesConstantine VII's Peri Ton Stratiotonpagolargo100% (1)

- The Kingdoms in Illyria Circa 400-167 B.C.Document16 pagesThe Kingdoms in Illyria Circa 400-167 B.C.pagolargoNo ratings yet

- Polybius On The Causes of The Third Punic WarDocument17 pagesPolybius On The Causes of The Third Punic WarpagolargoNo ratings yet

- Epaminondas and The Genesis of The Social WarDocument11 pagesEpaminondas and The Genesis of The Social WarpagolargoNo ratings yet

- The Fourth CrusadeDocument28 pagesThe Fourth CrusadepagolargoNo ratings yet

- GOT Episodes PDFDocument2 pagesGOT Episodes PDFdimmoNo ratings yet

- Digital Unit Plan TemplateDocument3 pagesDigital Unit Plan Templateapi-269190975No ratings yet

- Moderm Army CombactiveDocument481 pagesModerm Army CombactiveMossad News100% (22)

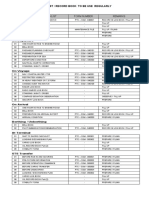

- Checklist - Log Book To Be Use RegularlyDocument1 pageChecklist - Log Book To Be Use RegularlymarissajungNo ratings yet

- Breyten BreytenbachDocument14 pagesBreyten BreytenbachtenialiterariaedicioNo ratings yet

- The Polish Army in 1939: InfantryDocument3 pagesThe Polish Army in 1939: InfantryAnonymous FFtXK4bnx0% (1)

- Solitary DefilementDocument40 pagesSolitary DefilementLucas De Carli75% (4)

- The Nagorno Karabakh Conflict - A Visual Explainer Dic2019Document7 pagesThe Nagorno Karabakh Conflict - A Visual Explainer Dic2019Tomi ListraniNo ratings yet

- War Griffons Titan Legion Army List: Forces Special RuleDocument7 pagesWar Griffons Titan Legion Army List: Forces Special RulemanoNo ratings yet

- Review of David R. Jones, - Military Encyclopedia of Russia and Eurasia - by Johanna GranvilleDocument5 pagesReview of David R. Jones, - Military Encyclopedia of Russia and Eurasia - by Johanna GranvilleJohanna Granville100% (1)

- Elemental Changeling Water SpyDocument61 pagesElemental Changeling Water SpyMorgan BloodrayneNo ratings yet

- The Subversion of Human Freedom in V For Vendetta' by Alan Moore. A Futuristic Approach and Comparative Analysis in Contemporary Modern SocietiesDocument28 pagesThe Subversion of Human Freedom in V For Vendetta' by Alan Moore. A Futuristic Approach and Comparative Analysis in Contemporary Modern SocietiesGILBERT NDUTU MUNYWOKI100% (1)

- Indo-Pak Relations: A Historical Overview of Major Disputes and Efforts to Build TrustDocument15 pagesIndo-Pak Relations: A Historical Overview of Major Disputes and Efforts to Build TrustSweetoFatimaNo ratings yet

- Traditional GamesDocument7 pagesTraditional GamesAngel Marie CahanapNo ratings yet

- EOD Letter of IntentDocument1 pageEOD Letter of IntentJackie_William_1935No ratings yet

- In Westminster AbbeyDocument5 pagesIn Westminster AbbeySharonNo ratings yet

- America's Midlife CrisisDocument281 pagesAmerica's Midlife CrisisSeanNo ratings yet

- History of The 208th Coast Artillery Regiment (AA) 10 Sep 45Document5 pagesHistory of The 208th Coast Artillery Regiment (AA) 10 Sep 45Peter DunnNo ratings yet

- Crack PlatoonDocument10 pagesCrack Platoonmana janNo ratings yet

- Emily Dickinson's ReadingDocument11 pagesEmily Dickinson's ReadingThiago Ponce de MoraesNo ratings yet

- Reporters HandbookDocument55 pagesReporters Handbookfemi adi soempenoNo ratings yet

- Example Step OutlineDocument17 pagesExample Step OutlineChristopher MendezNo ratings yet

- Japans Denial of War CrimesDocument6 pagesJapans Denial of War CrimesSaji JimenoNo ratings yet

- 1-48TACTICv0 2sDocument13 pages1-48TACTICv0 2smartin pattenNo ratings yet

- Los Días de La Calle Gabino Barreda - The Social Circle of RemedioDocument97 pagesLos Días de La Calle Gabino Barreda - The Social Circle of RemediomaiteNo ratings yet

- Sir John Jeremie - Experiences of Slave Society in St. Lucia !Document121 pagesSir John Jeremie - Experiences of Slave Society in St. Lucia !cookiesluNo ratings yet

- Sell - Battles of Badr and UhudDocument35 pagesSell - Battles of Badr and UhudChristine CareyNo ratings yet

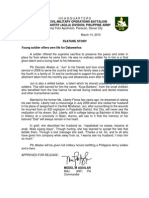

- Feature Story - Soldier Offers His Life For DabawenosDocument1 pageFeature Story - Soldier Offers His Life For Dabawenos10idphilippinearmyNo ratings yet

- Conflict Resolution SimulationDocument17 pagesConflict Resolution Simulationkarishma nairNo ratings yet

- Wood Elves FAQ 2008-05Document5 pagesWood Elves FAQ 2008-05John SmithNo ratings yet

![[Bowra] Homeric Epithets for Troy 1960 - 628372](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/721843195/149x198/316466a607/1712770400?v=1)