Professional Documents

Culture Documents

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC WS-JDE SPI-J076 00069

Uploaded by

EmmanuelUhuruOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC WS-JDE SPI-J076 00069

Uploaded by

EmmanuelUhuruCopyright:

Available Formats

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship

Vol. 12, No. 3 (2007) 295322

World Scientific Publishing Company

GHANAIAN AND KENYAN ENTREPRENEURS: A COMPARATIVE

ANALYSIS OF THEIR MOTIVATIONS, SUCCESS

CHARACTERISTICS AND PROBLEMS

HUNG MANH CHU

Department of Management

West Chester University, West Chester, PA 19383

CYNTHIA BENZING

Department of Economics and Finance

West Chester University, West Chester, PA 19383

cbenzing@wcupa.edu

cdbenzing@aol.com

CHARLES MCGEE

Department of Management

West Chester University, West Chester, PA 19383

Received June 2006

Revised December 2006

Three hundred and fifty-six entrepreneurs from Kenya and Ghana were surveyed to determine their

motivation for business ownership, variables contributing to their business success, and the problems

they encountered. Kenyan and Ghanaian entrepreneurs indicated that increasing their income and

creating jobs for themselves were leading factors motivating them to become business owners. Hard

work and good customer service were cited by both Kenyan and Ghanaian business owners as critical

for their success. But, compared to the Kenyan entrepreneurs, Ghanaians weighed support from family

and friends and external relationship building as more important. A weak economy is the most important

problem preventing entrepreneurs of both countries from achieving their goals. Ghanaian entrepreneurs

were more concerned about the inability to obtain capital, while Kenyan entrepreneurs were more

concerned about government regulations and problems related to business location.

Keywords: African entrepreneurs; motivation; business success; African business problems.

1. Introduction

The growth of jobs and GDP in developing countries is heavily dependent on the growth

and health of a countrys small business sector. As described by international agencies and

economists (IFC, 2000; Spring and McDade, 1998; Steer and Taussig, 2003), micro- and

small-sized enterprises (MSEs) are an important contributor to economic growth, household income and social stability. Both Ghana and Kenya recognize the importance of small

businesses and have taken actions to promote their growth. As one public utility official,

295

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

296 H. M. Chu, C. Benzing & C. McGee

Kwame Pianim, recently said, What we need is the vision and purposeful leadership to

unleash the abundant entrepreneurial talents of Ghanaians so the private sector can become

strengthened to assume the role of the engine of growth for the economy (Korantemaa,

2006). As described by Kenyan officials as early as 1992, the MSE sector in Kenya contributes to GDP, creates jobs, develops a pool of skilled labor for future needs, provides

managerial learning opportunities, increases the savings and investments of local Kenyans

and reduces poverty (Republic of Kenya, 1992).

During the 1960s and 1970s, Kenya enjoyed strong economic growth. But in the two

decades that followed, Kenyas economic performance deteriorated significantly. The average annual GDP growth rate declined from 6.5 percent during the 1960s and 1970s to about

1.3 percent between the years of 1996 and 2000, which was below the average population

growth rate of 2.2 percent (World Bank, 2006a). Kenyas economy turned a corner in 2002.

Since then, its real GDP has made impressive gains. According to the Kenyan government,

real GDP grew at 4.9 percent in 2004 and 5.8 percent in 2005, which exceeds the average

growth rate on the continent (Republic of Kenya, 2006).

As the first African colony to become independent from Great Britain, Ghana chose a

highly centralized, non-market technique to develop its economy. State owned enterprises

(SOEs) were integral to its national economic policy. Although these policies helped industrialize the country, they ultimately became a drag on the economy. Since the early 1980s,

Ghana has worked closely with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to liberalize trade

and investment, privatize SOEs and promote free markets. As a result, throughout the 1980s

and 1990s annual GDP growth averaged almost 4.5 percent and the poverty rate declined

from 50 percent to approximately 35 percent. During the 1990s, Ghanas economic growth

was slowed by higher oil prices and depressed cocoa and gold prices. Since 2000, Ghanas

economic picture has brightened with stronger GDP growth and a decline in its rate of

inflation. Ghana achieved 5.8 percent real GDP growth in 2004 (and 5.8 percent estimated

2005) which, like Kenyas rate, is higher than the average for the continent (International

Monetary Fund, 2005; World Bank, 2006b).

The strong economic growth of both countries has been tempered by double-digit inflation due, in part, to rising fuel costs and fiscal imbalances. In 2004, Kenya faced 11.6 percent

inflation, while Ghana experienced a 14.8 percent increase in prices in 2005 (Bank of Ghana,

2006; Republic of Kenya, 2005). Such inflation is destabilizing to the business sector and

especially small firms. Most small businesses face intense competition and consequently,

do not have the power to increase their prices to offset cost increases for raw materials or

supplies.

The MSE sector contributes to Kenyas and Ghanas economies by creating jobs and

reducing unemployment. In 1994, the MSE sector employed one-third of all working persons

in Kenya and was responsible for 13 percent of GDP (Republic of Kenya, 1995; Daniels

et al., 1995). According to a 1999 survey of MSEs, the Kenyan government found that

about 26 percent of households were engaged in some form of MSE activity (CBS, K-Rep,

and ICEG, 1999). In addition, the survey determined that the MSE sector contribution to

GDP had grown to approximately 30 percent (CBS, K-Rep, and ICEG, 1999). In Ghana,

70 percent of the business firms are microenterprises employing less than five persons and

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

Ghanaian and Kenyan Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Analysis 297

approximately 70 percent of the Ghanaian workforce is employed in micro, small, and

medium-sized enterprises (Government of Ghana, 2003; World Bank, 2006c). The vast

majority of households in Ghana are participating in some type of private sector activity

(Government of Ghana, 2003).

Most MSEs operate in the informal sector. (In Kenya, the small informal business

sector is known as the jua-kali.) Although these businesses avoid government scrutiny

and the expenses related to formal business registration, there are disadvantages to being

unregistered. An unregistered business does not have access to land titles or other property

rights for use as collateral and cannot have a bank account. Despite the drawbacks, MSEs

continue to remain largely in the informal sector of developing countries such as Kenya

and Ghana, providing significant jobs and income. Of the 459,000 jobs created in Kenya in

2005, 90 percent (414,000) were created in the informal sector (Republic of Kenya, 2006).

As of 2004, 77 percent of the workforce was employed in Kenyas informal sector (Republic

of Kenya, 2005). In Ghana, approximately 40 percent of the gross national income is the

result of informal sector activity (Government of Ghana, 2003).

Given the importance of MSEs, this study is designed to examine the motivations for

business ownership, the factors contributing to success and some of the problems encountered by entrepreneurs in Ghana and Kenya. The results can hopefully provide a better

understanding of entrepreneurial behavior in both countries and will yield some helpful

information for policy decision-makers.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Motivation

A number of surveys of entrepreneurs provide insight into the motivational aspects of the

entrepreneurial experience. Kuratko et al. (1997) and Robichaud et al. (2001) surveyed

North American entrepreneurs to determine how motivation relates to business success.

According to their studies, motivation falls into four categories: (1) extrinsic rewards; (2)

independence/autonomy;(3) intrinsic rewards; and (4) family security. Extrinsic rewards are

the economic reasons that motivate entrepreneurs to work, while intrinsic rewards are related

to self-fulfillment and growth. Because Kuratko et al. and Robichaud et al. concentrated

on the relationship between motivation and business success they did not indicate which

motivations were the strongest among entrepreneurs.

With respect to entrepreneurial motivation in developing countries, Swierczek and Ha

(2003) examined the motives of Vietnamese entrepreneurs. Swierczek and Has survey

concluded that challenge and achievement were significantly more important motivators

than were necessity and security. A study of motivation by Benzing, Chu and Callanan

(2005) discovered some regional differences in Vietnam, such that entrepreneurs in Ho Chi

Minh City were more motivated to start a business for personal satisfaction and growth,

while entrepreneurs in Hanoi were motivated by the need to create a job for themselves and

provide jobs for family members. Compared to Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi suffers from a

weaker economy and higher jobless rate, which may lead to greater security needs there.

In Romania, income needs were significantly stronger motivators than self-satisfaction and

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

298 H. M. Chu, C. Benzing & C. McGee

personal needs. The two strongest motivations were to increase income and to obtain job

security (Benzing, Chu and Szabo, 2005). In contrast, entrepreneurs in India were most

strongly motivated by the desire for independence/autonomy, i.e. to be their own boss. The

second strongest motivator was to increase their income (Benzing and Chu, 2005).

In Africa, Ugandas entrepreneurs indicated that making a living or making money is

the most important motivator for their business ownership (Bewayo, 1995). Results derived

from the survey also showed that a majority of entrepreneurs (61%) preferred business

ownership over working for a corporation because of autonomy, freedom and independence

(Bewayo, 1995).

Regarding the motivation for Kenyan entrepreneurs, Robertson (1998) suggested that

the diminishing amount of land available to women in Kenya is the single most important

factor motivating their involvement in trade. Another factor furthering womens business

ownership is their inability to access a Western type of education, which has become a

critical resource for Kenyans (Robertson, 1998).

According to a study by Chamlee-Wright (1997), Ghanaian entrepreneurs often invest

in a business because they have few other options. The majority of Ghanaians cannot entrust

their savings to a financial institution. In fact, in Ghana few financial institutions provide

interest-bearing investments for individual savings. With no stock market and interest rates

that fall behind the rate of inflation, Ghanaians often have no choice but to put money in

their own businesses and hope for a reasonable return on their investment.

Because of weak employment and savings opportunities in Kenya and Ghana, one may

speculate that business owners might be more motivated by extrinsic rewards such as increasing income and creating a job for themselves than by intrinsic rewards and autonomy. But,

unlike the Communist and former Communist countries such as Vietnam and Romania,

Kenya and Ghana have had a continuous entrepreneurial tradition. Thus, entrepreneurs in

Kenya and Ghana might better understand and be motivated by the intrinsic rewards and

satisfaction that emanate for business ownership. Learning more about business owners

motives could help policy-makers design incentives to foster entrepreneurial behavior, which

would strengthen the private sector, improve household income and encourage economic

development.

2.2. Perceived success characteristics

The factors that entrepreneurs believe contribute to their success are not unanimously agreed

upon by researchers. Most entrepreneurial research has concentrated on a few sets of factors: (1) the psychological and behavioral traits of entrepreneurs, (2) the managerial skills

and training of entrepreneurs and (3) the external environment. With regard to psychological traits, findings have been inconclusive. Dunkelberg and Cooper (1982); Markman and

Baron (1998); Shaver and Scott (1991); Solomon and Winslow (1998); and Stewart et al.

(1998) have not fully agreed on the traits that lead to business success. As pointed out by

numerous researchers (Covin and Covin, 1990; Dess et al., 1997; Frese et al., 2002; Rauch

and Frese, 1998), the effect of entrepreneurial orientation is often moderated by factors

such as environmental conditions. This study concentrates on the managerial skills, training

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

Ghanaian and Kenyan Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Analysis 299

and external environmental conditions that promote business success because these are the

factors that are most easily altered by policymakers.

Studies of entrepreneurs in developing countries (Busch, 1989; Huck and McEwen,

1991; Gosh et al., 1993; Yusuf, 1995) have been undertaken to determine the management

skills critical for their success. In Huck and McEwens (1991) study of Jamaican small

business owners, three skills were identified as the most important competency areas: management, planning and budgeting, and marketing/selling. Specific competencies within those

areas were maintaining financial records, possessing human relations skills and establishing

goals and objectives. In a study done by Yusuf (1995), South Pacific islanders considered

good management skills, access to financing, personal qualities and satisfactory government

support the most critical success factors.

In a study conducted among 25 Kenyan entrepreneurs, Neshamba (2000) found that the

owner-managers previous work experience and skills acquired on the job are important factors contributing to business success and growth. Other factors are: knowing the market and

understanding the needs of customers, access to capital, assistance from family members and

networking with friends from former schools and colleges. Finally, hard work, as evidenced

by long working hours, contribute to the success of an entrepreneur (Neshamba, 2000).

Based on a survey provided by the Kenya Management Assistance Program (K-MAP),

the availability of capital, possession of business skills, previous experience and support of

family members are essential for business success in Kenya (Pratt, 2001).

According to a survey conducted by McDade (1998), a number of personal and business

factors are related to the success of artisan entrepreneurs in Ghana. The acquired personal

factors are formal education, apprenticeship training, rural to urban migration and foreign

migration. Business characteristics such as receiving business loans, using outside traders

and innovating were also cited as factors contributing to business success among Ghanaian

artisans. Two other factors that were related to business success (higher revenue) were prior

experience in another business and the number of employees.

Entrepreneurs understand which factors would improve their prospects for business

success. Armed with this understanding, policy-makers can better assist entrepreneurs by

providing access to the skills and knowledge that they need.

2.3. Problems facing entrepreneurs

The problems facing entrepreneurs in developing countries are often quite similar. First,

entrepreneurs face an unstable, highly bureaucratic business environment. The laws governing African private enterprises, especially business registration and taxation systems, are

overly complex and difficult to understand. Contract and private property laws are often

poorly designed and/or enforced. As described by Kiggunda (2002) and Pope (2001), the

unfavorable institutional/regulatory environment is often accompanied by the added expense

of corruption and bribery. Research conducted on small businesses in East African countries

(Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda) shows that the private sector is overregulated and that regulations overlap and duplicate each other at central and local levels. Entrepreneurs are often subject to lengthy and costly delays in clearances and the approval process (Macculloch, 2001).

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

300 H. M. Chu, C. Benzing & C. McGee

One of the most serious problems facing African MSEs is limited access to short-term

and longterm financial capital. As suggested by Cook (2001); Gray et al. (1997); Levy

(1993); Little et al. (1987); Peel and Wilson (1996); and Spring and McDade (1998), most

small firms in developing countries do not obtain credit through formal financial institutions

because they cannot meet the collateral requirements or face exorbitant rates of interest. In

a study of Nigerian firms, Ariyo (2004) concluded that the most critical problem facing

Nigerian entrepreneurs is the lack of funding. Most new Nigerian small businesses are

not attractive candidates for bank lending because they are perceived as risky ventures.

Horns (1998) study of Zimbabwe concluded that small business growth was hampered

because bank policies would not accommodate small business loans. Morewagae et al.

(1995) reached a similar conclusion concerning Botswanas small business sector.

A survey of Kenyan entrepreneurs found that a lack of capital was the greatest problem

facing respondents (Gray et al., 1997). Although many Kenyan business owners did not

know how to apply for loans, those who did apply were rejected. It has also been reported

that the small business environment in Kenya is marked by repressive laws and restrictive

administrative behavior. Government officials are suspicious and sometimes hostile to profit

making. Kenyan entrepreneurs complain of long delays in obtaining trade licenses and

business registration, complicated tax forms, heavy control by government, and outright

misinterpretation of laws (Gray et al., 1997; Kenya Management Assistance Programme

Report, 1999; Pratt, 2001).

According to the World Bank and IMF experts, the number one problem faced by

Ghanaian entrepreneurs is insufficient access to credit (Chamlee-Wright, 1997). An earlier

study by Steel and Webster (1991) had reached the same conclusion. According to a 2002

government survey, other critical problems faced by Ghanaian entrepreneurs are: poor utility

connections; high tax rates; burdensome administration; corruption; and the unpredictability

of laws and regulations.

The corruption of government officials is a problem for both Ghanaian and Kenyan

entrepreneurs. In Chamlee-Wrights survey (1997), about 1,500 Accra traders per month

reported having their goods confiscated. In addition, they had to pay at least 5,000 cedis

(US$6.75) to the city each month. Six dollars and seventy-five cents can be the difference

between being able to feed the family and declaring bankruptcy. This fine, in many cases,

is a major source of income for the city councilmen and policemen.

The major problems reportedly facing entrepreneurs in Kenya and Ghana relate to government bureaucracy, lack of financing and corruption. This study will update previous

survey information to determine if these are still the major problems facing entrepreneurs.

To what extent have recent reforms in Kenya and Ghana removed these barriers to MSE

development? The current survey can assist policymakers by providing a means to evaluate

the reforms already instituted and a guide to future business sector reforms.

3. Survey and Methodology

The samples were chosen from the Chamber of Commerce membership directories for

Nairobi and Accra, the capital cities of Kenya and Ghana respectively. Every second entry

in the business directories was chosen for contact. Non-profit organizations, government

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

Ghanaian and Kenyan Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Analysis 301

owned enterprises (SOEs) and internationally owned enterprises were disregarded. If the

second entry did not fulfill the requirements or the business owner refused participation,

the next entry from the alphabetical list of institutions was contacted. The surveys were

conducted with the help of a Kenyan graduate assistant and a local Ghanaian high school

teacher. The method of filling out the questionnaire was a face-to-face meeting with the

owner. In all, 200 Kenyan business owners elected to participate in the survey, while 156

Ghanaian entrepreneurs agreed to be interviewed.

Since English is the official language used in Kenya and Ghana, the survey was written

and conducted in English. The questionnaire survey used in this study was similar to that

used with entrepreneurs in Vietnam, Romania and India (Benzing, Chu and Callanan, 2005;

Benzing, Chu and Szabo, 2005; Benzing and Chu, 2005). The motivation factors are similar

to those suggested in the work of Robichaud et al. (2001) and Kuratko et al. (1997). Many

problems listed in the survey are common to entrepreneurs in both transition and developing

countries.

Survey respondents were not asked about corruption and bribery due to the sensitive

nature of the problem. Entrepreneurs might be suspicious of a question about corruption

and might be inclined to end the interview.

The strengths of perceived success variables, motivation variables, and problems were

measured using a five-point Likert scale. A mean score for each item was calculated with

a higher mean score indicating greater importance. A two-sample, non-parametric test was

used to determine if Kenyan and Ghanaian entrepreneurs mean scores were significantly

different for a given item. A two sample t-test would not be appropriate because the data

are ordinal and non-normally distributed. The non-parametric test used in this study was

the Wilcoxon rank sum test (also called the Mann-Whitney test).

The item-by-item analysis was followed by a factor analysis to determine whether the

motivations, success variables and problems group together on significant factors. Correlation analysis, principal components analysis and a screen plot were used to establish the

factors. Then, a maximum likelihood, varimax rotation, factor analysis was used to determine

the factor loadings and communalities. The items that load on each factor were examined as

well as how the factors differ between Ghanaian and Kenyan entrepreneurs. To compare the

factors of Ghanaian and Kenyan entrepreneurs, the mean scores of summated scales were

computed and compared for Ghana and Kenya. The Mann-Whitney test was used again

because the summated scales were not normally distributed. (The same conclusions about

the country differences between factors were obtained when an F-test was used to determine

significant differences of summated scales.) While the factor analysis gives a broader view

of the differences by categorical factor, it obscures the individual differences. In addition,

some of the most important items did not load on any factor. As a consequence, both an

item-by-item analysis and a factor analysis are presented to enable the reader to appreciate

grouped and item differences among the motivations, success variables and problems.

Differences in the culture, politics and tribal heritage of entrepreneurs within each sample

and between samples could influence the validity of some results and the conclusions related

to those results. Thus, caution should be used in applying the results from the present study

to other developing countries as they may not be completely generalizable to other countries

in Africa or the world.

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

302 H. M. Chu, C. Benzing & C. McGee

4. Sample Characteristics

The characteristics of the businesses surveyed appear in Table 1. According to the European

Commissions definition (European Commission, 2005), a micro-enterprise employs less

than 10 full-time workers or full-time annual work units, while a small-sized enterprise

employs between 10 and 50. All businesses surveyed for this study employ less than 50

full-time workers and thus, can be classified as either micro- or small-sized enterprises

(MSEs).a Both samples are dominated by micro-enterprises with 85 percent of the Ghana

sample and 92 percent of the Kenya sample employing less than 10 full-time workers. Since

the majority of the businesses in all countries are microenterprises, the sample is consistent

with the larger world market. The sample is also consistent with the level of microenterprises

found in Africa. According to Spring and McDade (1998) and Manu (1999), 98 percent of

businesses in Africa have less than 10 employees.

Both samples are predominated by service businesses: 44 percent of the Kenyan sample

and 42 percent of the Ghanaian sample are categorized as providing a service. The Ghanaian

sample has more small manufacturers while the Kenyan group has a higher percentage of

retail businesses. In both the Kenyan and Ghanaian samples, most businesses were established by the owner. The average number of full-time workers is 4.9 in Ghana and 3.8 in

Kenya.

As shown in Tables 1 and 2, the average age of the business, the age of the respondents and

the gender mix are similar for the two surveys. The average age of the businesses in Ghana

and Kenya is 4.4 years and 4.8 years, respectively. The average age of the respondents is 35

and 33 years. Both samples also have a similar percentage of male and female entrepreneurs

with a little over one-third of both groups of respondents being female.

The sample averages differ with respect to sales and profitability. In comparison to the

Ghanaian businesses, the Kenyan businesses had a higher average sales and profitability.

Seventy-nine percent of the Kenyan businesses and 98 percent of the Ghanaian businesses

reported sales figure of US$60,000 or less. In addition, Ghanaian business owners were

less likely to disclose sales and profitability information; only 46 percent of Ghanaian

entrepreneurs disclosed sales figures while 78 percent of Kenyan entrepreneurs disclosed

this information. This could be the result of differences in tax structures, fear of government

awareness, and/or the interpersonal skills and trust established by the interviewer. In addition,

some cultures regard profit information as highly private and do not readily share such

information with non-family members. Ghanaians may maintain smaller businesses with

lower levels of sales and profits because their hourly commitment to the enterprise is less

than the Kenyan entrepreneurs.

The Kenyan and Ghanaian entrepreneurs worked fewer hours in their businesses than

entrepreneurs in other countries. Kenyan entrepreneurs reported working 45 hours on average per week, while Ghanaian entrepreneurs reported working 38 hours. In comparison

a The number of reported full-time workers is a proxy for the exact European Commission calculation of full-time

annual work units (AWU). The European Commission counts a part-time employee as a fraction of a full-time

employee. This survey, however, did not ask the number of hours that a part-time employee worked per week. As

a result, the exact full-time annual work units (AWU) cannot be determined.

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

Ghanaian and Kenyan Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Analysis 303

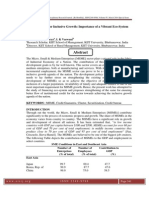

Table 1. Characteristics of Ghanaian and Kenyan businesses.

Ghana (N = 156)

Type of Business

Frequency

Percent

Kenya (N = 200)

Frequency

Percent

Type of Business

Retailing

31

20%

77

Wholesaling

9

6%

8

Service

64

42%

87

Manufacturing

32

21%

8

Agricultural products, tools, equip.

10

7%

11

Other

7

5%

7

Type of business ownership (Respondents could select more than one answer)

Established by you

119

111

Bought from another

7

14

Inherited

17

7

Independently owned

126

92

Partnership

11

26

Incorporated

0

10

Franchise

0

3

Average number of employees

Full-time

4.86

3.75

Part-time

1.13

1.95

Average age of business (years)

4.42

4.76

39%

4%

44%

4%

6%

4%

Not all survey respondents answered every question. For some questions more than one answer was

allowable which leads to a total number of answers greater than sample size. All percentages are based on

the number of entrepreneurs who answered the question.

Table 2. Characteristics of Ghanaian and Kenyan entrepreneurs.

Ghana

Kenya

Frequency

Percent

Frequency

Percent

Sex of respondents

Male

Female

98

56

64%

36%

124

67

65%

35%

Marital status

Married

Single

70

78

47%

53%

104

88

54%

46%

Average age of respondents

35.36 years

33.14 years

Average working hours per week

37.91 hours

45.40 hours

Educational level achieved

Frequency

Percent

Total

Percent

4

13

22

11

30

19

32

8

11

3%

9%

15%

7%

20%

13%

21%

5%

7%

1

6

9

12

27

17

59

18

39

1%

3%

5%

6%

14%

9%

31%

10%

21%

No formal education

Some grade school

Completed grade school

Some high school

Completed high school

Some college

Completed college

Some graduate work

Graduate degree

Not all survey respondents answered every question. All percentages are based on the number of

entrepreneurs who answered the question.

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

304 H. M. Chu, C. Benzing & C. McGee

to other studies of entrepreneurs in developing countries such as Vietnam, Romania and

India, the average hours worked are relatively low (Benzing, Chu and Callanan, 2005;

Benzing, Chu and Szabo, 2005; Benzing and Chu, 2005). Nineteen percent of the Ghanaian

entrepreneurs and 35 percent of the Kenyans worked 20 hours or less per week in their

businesses. These entrepreneurs may be working second jobs or running other businesses.

In contrast to small business owners in other regions of the world, African business owners

often own and operate several businesses simultaneously, which increases their diversification and reduces the risk of putting all their eggs in the same basket (Spring and

McDade, 1998). Although many entrepreneurs worked part-time in their business, those

who reported a full-time commitment worked extremely long hours. Fourteen percent of

the Kenyan entrepreneurs worked 84 hours or more per week.

Kenyan entrepreneurs in the sample had attained a higher level of education than their

Ghanaian counterparts. As shown in Table 2, 21 percent of the Kenyan entrepreneurs have

a graduate degree compared to seven percent of the Ghanaian entrepreneurs. According to

the U.S. State Department, Kenya has six state universities that enroll approximately 45,000

students, as well as six private universities. The World Bank (2006a) reports that the adult

male literacy rate in Kenya is 78 percent, while in Ghana it is 58 percent. During the last five

years, Ghana has made strides in educating its populace. Today, Ghana has a tuition-free

compulsory education program through primary and junior secondary school.

5. Results

5.1. Start-up advice, financing and marketing

Table 3 shows the results of questions related to start-up advice, capital and marketing.

When starting a business, both Kenyan and Ghanaian entrepreneurs draw heavily on the

advice of other business owners. In comparison to Ghanaians, Kenyan entrepreneurs rely

more heavily on friends and family members as a source of advice. Kenyan entrepreneurs

are also more likely to use multiple sources of advice. Thirty-five percent of Ghanaians and

30 percent of Kenyans used a legal advisor or financial advisor/lending institution.

The amount of start-up capital in Ghana averaged approximately US$4,000 with a

maximum of US$100,000 for the start-up of a flour mill. The Kenyan sample had an average

start-up cost of US$10,719 with a maximum of US$180,000 for an entrepreneur in the

transportation business. The Kenyan sample had a few large manufacturers, a processor

of cereals and a private primary school. These businesses had a high start-up cost, which

skewed the Kenyan average upward.

The major sources of financial capital are family and savings: 77 percent of Kenyans and

95 percent of the Ghanaians used personal savings and family to fulfill on-going financing

needs. Less than 20 percent of the entrepreneurs had ever used private banks, international

lending agencies or lending agencies sponsored by their government to obtain credit.

With respect to advertising, entrepreneurs in both countries rely on word-of-mouth and

free publicity to market their businesses. Only 21 percent of Ghanaian and 25 percent of

Kenyan entrepreneurs used paid advertising to market their businesses. This is similar to

entrepreneurs in other developing countries. Small entrepreneurs are less able to afford

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

Ghanaian and Kenyan Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Analysis 305

Table 3. Start-up advice and capital and business promotion for Ghanaian and Kenyan entrepreneurs.

Ghana (N = 156)

Freq.

Kenya (N = 200)

Percent

Freq.

percent

Before starting your business, from whom did you seek advice? (You may select more than one answer.)

Legal advisor

Finl advisor or lending institution

Friends

Family members

Other business owners

Other

Sought advice from no one

13

42

22

23

75

1

30

8

27

14

15

48

1

19

25

33

82

66

111

7

20

13

17

41

33

56

4

10

How much capital did you have to start your business?

Average (US$)

Standard deviation (US$)

Maximum capital (US$)

3,928

11,963

100,000

10,719

25,360

180,000

(N = 152)

(N = 198)

How do you promote your business? (You may select more than one answer.)

Paid advertisement

Word of mouth

Telephone directory

Free publicity

Good customer service

Posters/leaflets/billboards

Special offers; discounts; gifts

Other (website ,business cards, direct mail)

32

102

5

69

0

12

0

0

21

67

3

45

0

8

0

0

49

115

29

68

6

5

4

3

25

58

15

34

3

3

2

2

Questions that allow for more than one answer have a frequency that totals more than the sample size and,

therefore, percentages total to more than 100 percent.

advertising even though such advertising might help distinguish their product or service

from competitors.

5.2. Motivations

Respondents were asked to rate 12 reasons for deciding to own a business on a five-point

Likert scale with five (5) being extremely important and one (1) being unimportant.

As shown in Table 4, entrepreneurs in both Kenya and Ghana indicated that the top two

motivations for starting their own businesses were to increase my income and to create

a job for myself. These motivations correspond to Robichaud et al.s extrinsic rewards.

Given the high rates of unemployment in both countries (20 percent in Ghana and 40 percent

in Kenya), it is understandable that entrepreneurs would start a business to create a job.

There were no significant differences between the mean scores of Kenyan and Ghanaian

entrepreneurs on these two motivations.

The weak job market in Kenya and Ghana has driven many individuals to create jobs

for themselves by starting their own businesses. The same conditions have led to a weak job

market in both countries. First, there has been a slow down in the growth of the agriculture

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

306 H. M. Chu, C. Benzing & C. McGee

Table 4. Mean score for motivations of Ghanaian and Kenyan entrepreneurs (5 = extremely important, 4 = very

important, 3 = mildly important, 2 = not very important, 1 = unimportant).

Motivational Factors

1. To be my own boss

2. To be able to use my own past experience and training

3. To prove I can do it

4. To increase my income

5. To gain public recognition

6. To create job for myself

7. To provide jobs for family members

8. For my own satisfaction and growth

9. So I will always have job security

10. To build a business to pass on

11. Cannot find job appropriate to my background

12. To be closer to my family

Ghana

Kenya

Sig.

3.60

3.47

3.88

4.37

3.24

4.27

3.50

4.25

4.21

3.92

2.84

2.41

3.84

3.37

3.27

4.28

2.20

4.02

2.62

3.92

3.74

2.73

2.02

2.33

0.025*

0.705

0.000*

0.570

0.000*

0.198

0.000*

0.006*

0.001*

0.000*

0.000*

0.081

Significance level (two-tailed) obtained from a two-sample Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test. Mean scores that

are significantly different at the 95 percent level are designated with an asterisk. The level of significance is

adjusted for ties.

sector, which for decades has been the principal employer in both countries. Second, many

businesses have restructured and downsized their work force in an effort to become more

competitive and increase their profitability. Third, the governments have been forced to

drastically reduce their number of civil servants and privatize their SOEs as a condition

for receiving aid by the donor community. Finally, an increasing number of students who

graduate from high schools and universities have been unable to find employment. Many of

them have no choice but to become business owners.

There were significant differences among some other motivations. While the Kenyan

entrepreneurs were more motivated by the desire to be their own boss, Ghanaian

entrepreneurs were more motivated to prove they could do it, to gain public recognition

and to provide jobs to family members. The survey asked respondents to indicate how many

of their employees were family members and, in comparison to Kenyan entrepreneurs,

Ghanaian entrepreneurs appear to employ family members more intensively. Forty-six

percent of Ghanaian entrepreneurs employed at least one family member full-time, while

30 percent of Kenyan entrepreneurs indicated that they employed at least one family member

full-time.

Ghanaian entrepreneurs were also more motivated by the prospect of job security and

to build a business that could be passed on to other family members. This supports the

results obtained by Chamlee-Wright (1997). If Ghanaians have no other outlet for savings

due to poor financial sector development, then they will invest savings in a business with the

hopes of obtaining a reasonable return. The savings can then be passed along to progeny in

the form of an active and hopefully, successful business. To Ghanaian entrepreneurs, their

business may also serve as their primary legacy.

A factor analysis of the motivations of the total sample indicates that eight of the twelve

motivations load on three factors. The results of a maximum likelihood, varimax rotation,

factor analysis are shown in Table 5. The factors appear to be more closely aligned with career

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

Ghanaian and Kenyan Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Analysis 307

Table 5. Varimax rotated factor loadings (sorted) and communalities for motivation variables total data set.

Motivation

Factor 1

Factor 2

Factor 3

Communality

3. To prove I can do it

4. To increase my income

5. To gain public recognition

9. So I will have job security

8. For own satisfaction and growth

6. To create job for myself

7. To provide jobs for family

10. To build business to pass on

0.874

0.857

0.456

0.176

0.096

0.078

0.164

0.238

0.221

0.173

0.047

0.705

0.607

0.560

0.124

0.325

0.191

0.150

0.403

0.202

0.007

0.163

0.885

0.474

0.849

0.787

0.372

0.568

0.377

0.346

0.825

0.387

Variance

% Variance

1.836

0.230

1.380

0.172

1.295

0.162

4.511

0.564

success literature than entrepreneurial motivation literature. Consistent with the literature,

career success of business professionals can be measured by external or objective criteria as

well as internal or subjective criteria. (Friedman and Greenhaus, 2000; Greenhaus, 2002)

As shown, Motivations 3, 4 and 5 load on Factor 1. This factor best represents Objective

Career Success in that the entrepreneur is looking for tangible, external validation of his/her

accomplishments. Motivations 6, 8 and 9 load on a second factor that could be called Subjective Career Success in that the person who rates this factor highly is satisfying his/her

own internal wants and desires. Motivations 7 and 10 load on a third factor that could be

called a Legacy Effect whereby the person sees the business as a lasting legacy for his/her

family to be continued after the entrepreneur is no longer involved in the business. The

legacy factor is unique to entrepreneurs and does not appear in surveys of business professionals (Friedman and Greenhaus, 2000). Motivations 1, 2, 11 and 12 did not load on any

factors. A comparison of the summated scores on each factor show that there are significant differences between Ghanaian and Kenyan entrepreneurs, with Ghanaian entrepreneurs

Table 6. Mean scores and differences between Ghanaian and Kenyan entrepreneurs by factor related to motivation.

Mean scores

Summated scales

Scale 1 Factor 1:

Objective career success

Scale 2 Factor 2:

Subjective career success

Scale 3 Factor 3:

Legacy effect

Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test*

Ghanaian Entrepreneurs

Kenyan Entrepreneurs

Significance

3.8301

3.2663

0.000*

4.2489

3.9171

0.000*

3.7130

2.6560

0.000*

Summated scales were calculated as average score across items contained in that factor. Scale 1 is the average

of the scores on Motivations 3, 4 and 5; Scale 2 is the average of the scores on Motivations 6, 8, 9; and Scale 3 is

the average of the scores on Motivations 7 and 10.

Significance level (two-tailed) obtained from a two-sample Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test. Mean scores that are

significantly different at the 95% level are designated with an asterisk. The level of significance is adjusted for

ties.

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

308 H. M. Chu, C. Benzing & C. McGee

rating all three factors as more important than Kenyan entrepreneurs. While Ghanaians rate

the Legacy Effect (Factor 3) as more important than the Kenyan entrepreneurs, the mean

score for the family factor indicates that it is the least important factor in motivating both

groups of entrepreneurs. Both Ghanaians and Kenyans are most motivated by Factor 2.

5.3. Perceived success characteristics

On a five-point Likert scale with five (5) equal to extremely important and one (1) being

unimportant, data shown in Table 7 indicate that both Kenyan and Ghanaian entrepreneurs

ranked hard work as the most important factor contributing to business success with customer

service as the second most important variable. Other important characteristics to both groups

of entrepreneurs were good management skills, friendliness, access to capital, previous

business experience and the ability to maintain accurate records.

There were significant differences between the Kenyan and Ghanaian entrepreneurs.

Ghanaian entrepreneurs view previous business experience and the ability to maintain accurate records as more important than Kenyan entrepreneurs. In general, Ghanaians rate all

the management skills more highly than their Kenyan counterparts. Ghanaians may be

more conscious of these skills because they have feelings of inadequacy surrounding them.

Based on previous answers, the Ghanaian entrepreneurs are less educated than the Kenyan

entrepreneurs. This lack of educational background may translate into an inability to maintain accounting records, etc.

Table 7. Mean score for variables contributing to business success (5 = extremely important,

4 = very important, 3 = mildly important, 2 = not very important, 1 = unimportant).

Success Variables

1. Good management skills

2. Charisma: Friendliness

3. Satisfactory govt. support

4. Appropriate training

5. Access to capital

6. Previous business experience

7. Support of family & friends

8. Marketing/Sales promotion

9. Good product at competitive price

10. Good customer service

11. Hard work

12. Good location

13. Maintenance of accurate records

14. Ability to manage personnel

15.Community involvement

16. Political involvement

17. Reputation for honesty

Ghana

Kenya

Sig.

4.54

4.57

3.74

3.45

4.41

3.58

3.78

3.19

4.52

4.68

4.74

4.37

4.40

3.88

3.61

2.49

4.55

4.27

4.26

2.51

3.50

4.31

2.97

3.16

3.36

4.05

4.42

4.50

3.95

3.96

3.59

2.60

1.67

4.11

0.003*

0.002*

0.000*

0.537

0.373

0.000*

0.000*

0.064

0.000*

0.000*

0.005*

0.000*

0.001*

0.050*

0.000*

0.000*

0.002*

Significance level (two-tailed) obtained from a two-sample Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test. Mean

scores that are significantly different at the 95 percent level are designated with an asterisk.

The level of significance is adjusted for ties.

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

Ghanaian and Kenyan Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Analysis 309

Ghanaians also rate support from family and friends as more important than Kenyan

entrepreneurs. Ghanaian business owners appear to rely more heavily on this support as

well. When asked in a separate question to rate the level of support from family and friends,

82 percent of Ghanaian entrepreneurs reported substantial or very substantial support. In

contrast, 51 percent of Kenyan entrepreneurs reported such support.

Community involvement and political involvement are more important to entrepreneurs

in Ghana, but, surprisingly, political involvement is the least important success variable

for entrepreneurs from both countries. According to surveys by the World Bank (2003),

Kenyan entrepreneurs expect to pay 2.91 percent of sales in unofficial payments to get

things done. This compares to 1.72 percent for firms in sub-Sahara Africa. Thirty-seven

percent of the Kenyan firms surveyed by the World Bank expect to give gifts in meetings

with tax inspectors compared to 16 percent in sub-Sahara Africa. Although a World Bank

survey has not been done of Ghanaian entrepreneurs, Kenyan entrepreneurs face higher

levels of corruption and expected payoffs than entrepreneurs in the sub-Saharan region as a

whole. Despite the existence of payoffs and corruption, this did not translate into a higher

mean score for political involvement.

Because the Ghanaian government has historically maintained a heavy presence in the

economic and business environment, it is understandable that Ghanaians would attribute

more importance to government support than Kenyans would. Ghanaians also believe a

reputation for honesty is more important than Kenyans, but both groups of entrepreneurs

rated this as a very important characteristic for success.

A factor analysis of the significant factors indicates that 12 of the 17 success variables

can be grouped into three factors. (Items 4, 5, 7, 8 and 12 did not load on any significant

factors.) As shown in Table 8, Factor 1 includes Items 2, 9, 10, 11 and 17. This factor contains

items with an internal locus of control and therefore, can be called Internal Factors. As

shown by the summated scales in Table 9, entrepreneurs in both Ghana and Kenya rate

Factor 1 as the most important factor in their business success. This shows optimism and a

Table 8. Varimax rotated factor loadings (sorted) and communalities for success variables (total data set).

Success variables

Factor 1

Factor 2

Factor 3

Communality

10. Good customer service

2. Charisma: Friendliness

9. Good product/competitive price

11. Hard work

17. Reputation for honesty

3. Satisfactory govt. support

16. Political involvement

15. Community involvement

6. Previous business experience

14. Ability to manage personnel

13. Maintenance of accurate records

1. Good management skills

0.892

0.602

0.564

0.491

0.450

0.105

0.001

0.186

0.064

0.080

0.284

0.446

0.003

0.070

0.202

0.010

0.095

0.840

0.672

0.644

0.523

0.304

0.291

0.092

0.081

0.099

0.117

0.306

0.371

0.088

0.077

0.294

0.177

0.668

0.546

0.509

0.803

0.377

0.373

0.334

0.350

0.724

0.458

0.536

0.309

0.546

0.463

0.466

2.256

0.188

2.086

0.174

1.397

0.116

5.739

0.478

Variance

% Variance

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

310 H. M. Chu, C. Benzing & C. McGee

Table 9. Mean scores and differences between Ghanaian and Kenyan entrepreneurs by factor related to success

variables.

Mean Scores

Summated scales

Scale 1 Factor 1:

Internal factors

Scale 2 Factor 2:

External relationships

Scale 3 Factor 3:

Management skills

Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test*

Ghanaian entrepreneurs

Kenyan entrepreneurs

Significance

4.621

4.273

0.000*

3.356

2.398

0.000*

4.274

3.943

0.002*

Summated scales were calculated as average score across items contained in that factor. Scale 1 is the average

of the scores on success variables 2, 9, 10, 11, and 17; Scale 2 is the average of the scores on success variables

3, 6, 15, 16; and Scale 3 is the average of the scores on success variables 1, 13, and 14.

Significance level (two-tailed) obtained from a two-sample Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test. Mean scores that are

significantly different at the 95% level are designated with an asterisk. The level of significance is adjusted

for ties.

belief that their own behavior (hard work, friendliness, honesty and customer service) and

having a good product hold the key to developing and maintaining a successful business.

Factor 2 includes Items 3, 6, 15 and 16. This factor places political involvement, community

involvement and government support in the same factor and, thus, might be called External

Relationships. The low mean score on this factor (Table 9) indicates that both Ghanaian

and Kenyan entrepreneurs rate such external relationships as relatively unimportant in their

business success. Factor 3 can be referred to as Management Skills because it includes

Items 1, 13 and 14. These three skills are relatively important to both groups, but as shown by

the item analysis in Table 7, management skills are viewed as more important to Ghanaian

entrepreneurs than Kenyan entrepreneurs.

5.4. Problems

When asked to identify the problems faced by entrepreneurs in opening and running their

businesses, several concerns were rated as serious problems. Respondents answered the

questions by indicating their opinion on a five-point Likert scale in which five (5) is a very

serious problem and one (1) is not a problem. As Table 10 shows, the most critical

problem faced by both Ghanaian and Kenyan entrepreneurs is a weak economy. Other

serious problems in both countries are too much competition and the inability to obtain

short-term and long-term financial capital.

The perception that both countries have weak economies has real validity to MSE

entrepreneurs. Despite healthy GDP growth rates, high poverty rates and unemployment

rates can seriously affect demand for goods and services. For example, the economy of

Kenya grew at an estimated 5.8 percent rate in 2005, yet it continues to suffer high unemployment (40 percent estimated in 2001) and a high poverty rate (U.S. CIA, 2006). During

the last three years, Kenya has fallen 20 places in the United Nations prosperity rankings

and now ranks 154 out of 177 countries. Kenya has gone from being a middle-income

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

Ghanaian and Kenyan Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Analysis 311

Table 10. Problems faced by small businesses (5 = very serious problem, 4 = serious problem, 3 = problem,

2 = minor problem, 1 = not a problem).

Problems

1. Unreliable and undependable employees

2. Too much competition

3. Unable to obtain short-term financial capital

4. Unable to obtain long-term financial capital

5. Too much government regulation

6. Limited parking

7. Unsafe location

8. Weak economy

9. Lack of management training

10. Lack of marketing training

11. Inability to maintain accurate acct. records

12. Business registration process/tax system

Ghana

Kenya

Sig.

2.72

3.49

3.97

3.99

2.81

1.74

2.08

4.11

2.83

2.80

3.14

2.49

3.46

3.66

3.41

3.39

3.21

2.31

3.18

4.18

3.09

2.96

3.16

3.28

0.000*

0.261

0.000*

0.000*

0.003*

0.000*

0.000*

0.068

0.047*

0.135

0.796

0.000*

Significance level (two-tailed) obtained from a two-sample Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test. Mean scores that are

significantly different at the 95 percent level are designated with an asterisk. The level of significance is adjusted

for ties.

country to a low-income country that can no longer be expected to meet its Millennium

Development Goals. In addition, the World Bank has placed a $260 million aid package on

hold in response to the 2006 corruption scandal referred to as the Anglo Leasing affair. The

corruption charges that are plaguing the current government have chilled foreign investment

and aid, and reduced potential economic growth rates in Kenya (BBC News, August 9, 2005;

BBC News, March 2, 2006).

Ghana also suffers the problems of a low income country in that its unemployment rate

hovers around 20 percent and the poverty rate in 2005 was 35 percent. In addition, approximately 60 percent of the work force is employed in agriculture (U.S. CIA, 2006; DFID,

2006; Ghanaweb, 2006). However, the future economic picture for Ghana is more optimistic

than that of Kenya. In April 2006, the World Bank announced that Ghana would receive

full debt relief from the World Bank, the IMF and the African Development Fund (World

Bank, 2006d). Overall, the IMF has given a positive assessment of Ghanas macroeconomic

management and its more open trade and investment policies (International Monetary Fund,

2005; Korantemaa, 2006). Ghana has also gained eligibility for Millennium Challenge funds.

Although both countries may benefit from strong economic growth in the coming years,

Ghana has the edge because of its more transparent economy, less corrupt government and

stronger macroeconomic policies.

With respect to competition, it is understandable that MSE entrepreneurs would perceive

competition as a major problem. Much of the MSE activity occurs in the informal sector,

which is characterized by ease of entry, unregulated and competitive markets, reliance on

indigenous resources, family ownership and small-scale operation (Thomas, 1992). These

characteristics make it easy for competitors to start and stay in business. Entrepreneurs in

other studies (Benzing, Chu and Callanan, 2005; Benzing, Chu and Szabo, 2005) also rated

competition as a major problem.

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

312 H. M. Chu, C. Benzing & C. McGee

Government regulation and bureaucracy were not ranked in the top five problems by

entrepreneurs in either Ghana or Kenya. Although a study done by Amponsah (2000) found

that a majority of entrepreneurs (58.4 percent) thought the bureaucratic authorities in Ghana

were unreasonable, government regulation was not listed here as one of the most pressing

problems. This may result from the informal status of most MSEs.

While entrepreneurs in both countries show no significant differences in their concerns over the weak economy and competition, it is the differences between the mean

scores on individual items and factors that prove the most interesting. For instance, why

do Kenyan entrepreneurs report greater frustration with the business registration process

and tax system than their Ghanaian counterparts? This difference is also observed in

the factor analysis (Table 12) with Kenyan entrepreneurs recording a higher mean score

on the governmental barriers factor. Using World Bank data (2006e), it actually takes

longer and costs more to register a business in Ghana than it does Kenya (81 days versus

54 days), so one might assume that the real problem in Kenya is more closely related to

tax rates. According to the World Bank, a medium sized business in Kenya must make 17

tax payments per year and pay 68 percent of gross profit in taxes, while a similar business in Ghana must make 35 payments and pay 45 percent of gross profit in taxes. While

Ghanas rate is comparable to the OECD rate, Kenyas tax rate is far too high (World Bank,

2006f ).

As shown in the item analysis in Table 10 (and in the factor analysis in Table 12), there

is a significant difference between the mean scores for locational safety (referred to as the

locational attributes factor). Kenyan entrepreneurs in Nairobi have greater fear of safety than

their counterparts in Ghana. With a population of 3.5 million, Nairobi has faced escalating

levels of violent crime as a result of rising income inequality, poverty, unemployment and

population growth (Gimode, 2001). According to one top UN official, Nairobis crime

problem is a bigger barrier to investment and business development than corruption (BBC

News, March 21, 2006). According to a 2002 United Nations (UN-HABITAT) survey of

crime in Nairobi, 37 percent of the respondents had been a victim of robbery during the most

recent year. Crime and safety problems have economic repercussions. Nairobi shop-owners

and service suppliers face increased costs because they must pay for private security, pay for

losses related to robbery and often end their day early to avoid crime. According to a survey

done by the World Bank (2003), Kenyan entrepreneurs report that security costs 1.94 percent

of sales, which is higher than the average for sub-Sahara Africa of 1.19 percent. The city has

developed a Police Service Strategic Plan designed to institute reforms such as increasing

police salaries and the ratio of police officers to the public. The current ratio of officers to

persons in Nairobi is 1:1,150. This is in marked contrast to the UN-recommended ratio of

1:450. As evidence of reforms already taken, Nairobi police were given a 115 percent salary

increase in 2004 and more police have been hired. These actions may be partly responsible

for a decrease in property crimes during 2005. Residents have also instituted community

policing in an attempt to reduce crime (Dahl, 2006; Mulama, 2006; Afrol News, December 5,

2005).

In contrast, Ghanaians appear to be fairly satisfied with how government is handling

crime. According to a survey by AfroBarometer (2006), 71 percent of Ghanaians in 2005

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

Ghanaian and Kenyan Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Analysis 313

thought the government was handling crime fairly well or very well. This was a 15 percent

improvement from 2000.

In both the individual item analysis in Table 10 and the factor analysis in Table 12,

obtaining capital emerged as a serious problem for both groups of entrepreneurs. However,

Ghanaian entrepreneurs appear to face greater constraints obtaining short-term and longterm capital. There are a number of explanations for this difference. First, firm size and firm

revenue have been found to influence an entrepreneurs ability to obtain commercial bank

credit (Kariuki, 1995). Since the Kenyan firms reported higher business revenue and income

than the Ghanaian sample, they may have been better able to secure credit. Second, higher

business income can also reduce the need for external funds. According to Atieno (2004),

most entrepreneurs in Kenya still use personal savings and/or retained earnings as a major

source of financing. A higher business income would increase savings, which would reduce

the need for an outside source of funds. Again, the fact that Kenyan firms reported higher

business revenue and income may make them less dependent on external funding. Third,

Ghanaian entrepreneurs might face greater capital constraints than the Kenyan entrepreneurs

because a greater percentage of the Ghanaian sample was in manufacturing. In general,

manufacturing requires greater on-going capital input to purchase equipment, tools, and

raw material. Lastly, according to two recent studies, Kenyans understand how to obtain

credit in a credit-constrained environment. It has been shown that firms in Kenya often

borrow for a stated purpose only to divert those funds to a different purpose for which

funding would have been more difficult to obtain (Atieno, 2004). Vandenbergs (2003)

study of small manufacturing firms found that Kenyan MSEs often use irregular means

of obtaining credit. For instance, they might use customer purchase orders to obtain trade

credit from suppliers, ask for down payments from customers or buy needed equipment on

an installment plan. It is possible that these irregular means of accessing funds are more

developed in Nairobi than they are in Accra.

As shown in Table 11, 10 of the 12 problem items loaded onto four factors. Factor 1

includes Items 9, 10 and 11 and can be called Management Skills. Factor 2 includes

Table 11. Varimax rotated factor loadings (sorted) and communalities for problem variables (total data set).

Problem variables

Factor 1

Factor 2

Factor 3

Factor 4

Communality

9. Lack of management training

10. Lack of marketing training

11. Maintaining acct. records

3. Short-term financial capital

4. Long-term financial capital

2. Too much competition

5. Too much govt. regulation

12. Registration/tax system

7. Unsafe location

6. Limited parking

0.978

0.738

0.417

0.081

0.099

0.018

0.045

0.156

0.263

0.082

0.009

0.050

0.232

0.809

0.674

0.387

0.098

0.040

0.026

0.006

0.199

0.060

0.031

0.029

0.080

0.011

0.981

0.458

0.102

0.227

0.064

0.201

0.194

0.020

0.234

0.101

0.159

0.330

0.685

0.466

1.000

0.591

0.267

0.661

0.526

0.161

1.000

0.345

0.550

0.275

Variance

% Variance

1.794

0.179

1.327

0.133

1.286

0.129

0.969

0.097

5.376

0.538

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

314 H. M. Chu, C. Benzing & C. McGee

Table 12. Mean scores and differences between Ghanaian and Kenyan entrepreneurs by factor related to problem

variables.

Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test

Mean scores

Summated scales

Scale 1 Factor 1:

Management skills

Scale 2 Factor 2:

Financial considerations

Scale 3 Factor 3:

Governmental barriers

Scale 4 Factor 4:

Locational attributes

Ghanaian Entrepreneurs

Kenyan Entrepreneurs

Significance

2.927

3.074

0.185

3.814

3.482

0.003*

2.644

3.253

0.000*

1.913

2.722

0.000*

Summated scales were calculated as average score across items contained in that factor. Scale 1 is the average

of the scores on problem Variables 9, 10, and 11; Scale 2 is the average of the scores on problem Variables 2, 3,

and 4; Scale 3 is the average of the scores on problem Variables 5 and 12; Scale 4 is the average of the scores on

problem Variables 6 and 7.

Significance level (two-tailed) obtained from a two-sample Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test. Mean scores that are

significantly different at the 95 percent level are designated with an asterisk. The level of significance is adjusted

for ties.

Items 2, 3 and 4 which relates to Financial Considerations. Factor 3 contains Problems 5 and 12 and can be called Governmental Barriers, while Factor 4 which contains

Problems 6 and 7 can be referred to as Locational Attributes. Based on the summated

scales reported in Table 12, Kenyan entrepreneurs perceive Governmental Barriers and

Locational Attributes as more serious problems than Ghanaians. Although both groups of

entrepreneurs rated Factor 2, Financial considerations as the most serious factor, Ghanaian entrepreneurs believe they are more hampered by financial constraints. There was no

significant difference between Kenyan and Ghanaian entrepreneurs when it came to the

management skills factor. As discussed above, the results of the factor analysis largely

support the earlier item-by-item analysis.

6. Discussion

Both Kenya and Ghana recognize the importance of their MSE sector. As a result, they

have developed strategies to create friendlier business environments. According to Ghanas

National Medium Term Private Sector Development Strategy (Government of Ghana, 2003),

private sector development has been constrained by taxes, levies and fees, as well as the

inability to obtain capital and limited managerial skills. A major part of Ghanas development

plan (Government of Ghana, 2003) is to remove physical and regulatory constraints. The

development plan targets specific export industries for additional incentives and funding.

This direct interventionist approach is based on the observable success of the Southeast

Asian tigers (Government of Ghana, 2003).

The Kenyan government has also developed a strategy to improve the business environment. Working with the World Bank, the Kenyan Ministry of Trade and Industry (MoTI)

has implemented the MSME Competitiveness Project. The project plans to simplify the

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

Ghanaian and Kenyan Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Analysis 315

tax regime for MSEs, set up a one-stop approach to business registration, and provide

business skills training (World Bank, 2006g). The plan also addresses security problems

in Nairobi and infrastructure problems related to the roads and electrical power (Kituyi,

2005). The governments proposed restructuring and privatization of the state-run enterprise, Telkom Kenya, is another way to reduce the cost of doing business by reducing telecommunications costs (World Bank, 2006a).b Kenyas comprehensive Economic

Recovery Strategy for Wealth and Employment Creation proposes to modernize Kenyas

tax administration, reduce corruption in government, reform public security and reduce

bureaucratic obstacles to MSEs (Republic of Kenya, 2003). According to the World Bank

(2006e), Kenya has already shortened the business registration process from 62 days in

2004 to 54 days in 2005. In 2000, Kenya combined 16 individual business licenses into one,

which significantly reduced the licensing process. Despite this improvement, local governments still require annual renewals of licenses, which is an unnecessary burden (Kituyi,

2005).

As indicated by the factor analysis of problems, entrepreneurs in both Kenya and Ghana

view financial considerations as their most serious problem. Kenyas and Ghanas commercial banks are often unwilling to provide loans to MSEs for a number of reasons. First,

small loans are expensive to supervise and process and are inherently riskier than loans to

large firms. When small undercollateralized loans fail, banks have to absorb the loss because

it is too costly to try to recover the loan. In addition, banks prefer to deal with registered

businesses (i.e., businesses in the formal sector) and most MSEs operate in the informal

sector (Isaksson, 2004). Finally, banks require a business plan and/or accurate accounting

records, which many MSEs cannot provide (Tagoe et al., 2005).

In Kenya, the credit gap has been partially met by NGOs that specialize in microfinancing. In addition, Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCAs) provide small

business loans to their members. According to Atieno (2004), most Kenyan MSEs use informal institutions for savings and less than 50 percent use credit from any source. A survey

performed by the World Bank (2003) found that 53 percent of Kenyan firms used internal

means of financing and 32 percent used commercial bank loans or credit. Although 32 percent may seem low, compared to other sub-Saharan and developing countries this is actually

an impressively high number since in sub-Saharan countries as a whole, an average of 20

percent of firms use commercial bank loans or credit (World Bank, 2003). As evidenced by

the survey in this paper, Kenyan entrepreneurs appear to face less capital constraints than

Ghanaian entrepreneurs.

In Ghana, there are a number of alternative institutions and means of obtaining credit, but

awareness of these opportunities may be limited and the lending strategies are geared toward

manufacturing/export enterprises. Some of the major players in small business lending in

Ghana are: the NBSSI, EMPRETEC, IFC, APDF and ADF. For a good summary of the

funding opportunities available to Ghanaian SMEs, see Frempong (2004). Ghana needs to

b Privatization of Telkom Kenya has already been postponed a number of times since 2000. In June 2006, the sale

of Telkom Kenya was postponed again until the state-run enterprise can be made profitable. (The East African,

May 16, 2006)

September 8, 2007 11:56 WSPC

WS-JDE SPI-J076

00069

316 H. M. Chu, C. Benzing & C. McGee

continue working to make funding available to MSE entrepreneurs in retail and service

businesses.

While both groups of entrepreneurs believed that internal factors were the most important set of success attributes, they ranked the management skills factor as the second most

important success factor. To meet this need, both countries must expand their existing

business consulting services. Two of Kenyas consulting initiatives: K-MAP (Kenya Management Assistance Program) and the voucher program should be revitalized. K-MAP is a

consortium of 47 large and well-established companies that provides one-on-one business

counseling to existing and potential entrepreneurs (Pratt, 2001). Kenya, in conjunction with

the World Bank, has also experimented with a voucher program designed to provide MSEs in

the Jua Kali sector with training, technology and business development services (Tan, 2005).

Ghana utilizes many institutions (NBSSI, ADF, APDF, EMPRETEC, etc.) for consulting

services. In addition, the Promotion of the Private Sector (PPS), a collaboration between the

Federal Republic of Germany and Ghana, provides consulting services to the government

and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to promote private sector development

(PPS Ghana, 2006). Compared to Kenyas consulting outreach services, Ghanas appear to

be less developed.

7. Summary and Recommendations

Entrepreneurs in both Kenya and Ghana indicate that the top two motivations for starting their businesses are to increase income and create a job for themselves. Kenyan

entrepreneurs appear to be more motivated by independence and self-satisfaction than

Ghanaian entrepreneurs. Since both countries have a high unemployment rate, it is understandable that entrepreneurs would create a business to provide self-employment. Knowing

that high rates of unemployment (especially among the young) can lead to social unrest,

government officials have every reason to encourage the creation of businesses by reducing

regulatory and tax burdens, providing financial support and teaching the unemployed how

to start a business.

Ghanaian entrepreneurs are also more motivated than Kenyan entrepreneurs by a legacy

effect factor that includes the ability to provide jobs for family members and to pass on

their businesses. With this knowledge, Ghanaian policymakers could design tax laws that

provide incentives to those who create a business to pass on or receive a business as part of

an inheritance.

Kenyan and Ghanaian entrepreneurs agree that hard work and high quality customer

service are the two most important success variables. While they also agree that access

to capital is important, there was a sharp contrast in their evaluation of the importance of

government support. Compared to Kenyan entrepreneurs, Ghanaian entrepreneurs believe

that government support is a necessary ingredient for success.