Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Accounting Rate of Return

Uploaded by

Kelly HermanOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Accounting Rate of Return

Uploaded by

Kelly HermanCopyright:

Available Formats

Accounting Rate of Return

Theoretical Background

The accounting rate of return (ARR), or alternatively the book rate of return, is a

popular rule of thumb capital budgeting technique used by managers of firms to

evaluate real investment projects (Hillier, Grinblatt and Titman, 2008).

The

accounting rate of return is essentially a simple financial accounting ratio which

provides an estimate of projects worth over its useful life.

A number of different variations on the basic accounting rate of return formula exist.

However, the main formula is usually defined as the average accounting profit

earned on an investment divided by the average amount of capital invested (Hillier,

Grinblatt and Titman, 2008). The accounting rate of return is similar to the financial

accounting ratios of the return on investment (ROI) or the return on assets (ROA)

(Brealey, Myers & Allen, 2008).

The formula is generally defined as follows:

Accounting Rate of Return = Average Accounting Profit / Average Investment

The accounting rate of return is expressed as a percentage. This rate of return is

then compared to the required rate of return/target hurdle rate. If the accounting rate

of return is higher than the required rate, then the proposed project will be accepted.

In contrast, if the accounting rate of return is less than the required rate, the project

will be rejected (Hillier, Grinblatt and Titman, 2008).

Thus, when comparing

investments, the higher the accounting rate of return, the more attractive an

investment is.

There are several advantages to using the accounting rate of return as a capital

budgeting technique. As Bester (nd) notes, the main advantage of the accounting

rate of return is that it is relatively simple and easy to understand and calculate, thus

allowing managers to use the measure as a quick estimate with which to compare

investments.

However, despite the above advantages, the accounting rate of return has

numerous, distinct disadvantages. An important weakness of the technique is that it

makes use of accounting profit (book values) which may be very different to the cash

flows generated by a project or investment, as Hillier, Grinblatt and Titman (2008)

state.

Thus the accuracy of the method may be affected by different accounting

practices used by firms such as different methods for depreciating capital

investments (Brealey, Myers & Allen, 2008). Furthermore, as Bester (nd) notes, the

accounting rate of return fails to consider the time value of money which may lead to

an artificially high level of return for investments. In addition, the method does not

increase risk for longer term forecasts.

Thus it can be concluded, that there are several shortfalls to using the accounting

rate of return and as such, it should not be used as a primary or exclusive capital

budgeting technique (Brown, 1961). Rather the accounting rate of return should be

a useful tool when used with full recognition and understanding of its limitation

(Brown, 1961). This is further supported by MacIntyre and Icerman (1985) who state

that the numerous shortfalls of the accounting rate of return often cause its use in

capital budgeting analysis to be misleading and can result in non-optimal investment

decisions. In addition, Brealey, Myers & Allen (2008) state that the accounting rate

of return may not be a good measure of true profitability when evaluating

investments. Thus as will be shown in the empirical evidence below, the practical

use of the accounting rate of return in capital budgeting analysis is limited.

Empirical Evidence

International Evidence

Numerous international studies conducted on capital budgeting techniques

employed by firms, generally have indicated that the accounting rate of return is not

a method used by the majority of firms. In a study conducted by Graham and Harvey

(2001), it was found that 20.29% of U.S. firms always or almost always use the

accounting rate of return as a capital budgeting technique. This is a relatively low

percentage when compared to the usage of discounted cash flow techniques such

as the NPV and IRR methods. A study by Ryan and Ryan (2002) showed that 15%

of U.S. firms preferred to use this method. The unpopularity of the accounting rate of

return is further illustrated in a capital budgeting survey of European firms conducted

by Brounen, de Jong and Koedijk (2004).

This study found that in the U.K.,

Netherlands, Germany and France, 38.10%, 25.00%, 32.17% and 16.07%

respectively, of firms use the accounting rate of return. Thus from the above studies,

it is evident that the accounting rate of return is not a primary technique used by

firms when analysing capital investment projects.

South African Evidence

The results of empirical studies conducted in South Africa are generally similar to the

results concluded in international studies about the use of accounting rate of return.

A study by Du Toit and Pienaar (2005) showed that firms used the accounting rate of

return as a primary capital budgeting method only 11.3% of the time. When asked

to identity all capital budgeting methods used, the accounting rate of return was

used by 35.9% of firms.

In contrast, Correia & Cramer in their 2008 survey,

determined a much lower preference of firms using the accounting rate of return only 14% of firms almost or always almost employ it as a capital budgeting tool.

Furthermore, Correia, Flynn, Uliana and Wormald (2007) show in their study from

1972-1995, that there has been a decline in the use of the accounting rate of return

in favour of an increase in the use of NPV and IRR (Correia & Cramer, 2008). In

addition, in the study of firms in the Western Cape Province of South Africa, it was

found that the accounting rate of return was the least used capital budgeting

technique (Brijlal & Quesada, 2009).

Thus from the above empirical evidence found in both international and South

African studies, it can be concluded that the accounting rate of return is not a primary

method used by firms when evaluating capital investment decisions, rather it is used

as a supplementary method to other more popular techniques. The evidence shows

that there has been a significant decline in the use the accounting rate of return and

the main reason for this, as stated by Correia and Cramer (2008), is that there may

be a lack of understanding of how the accounting rate of return is defined.

You might also like

- Makerere University College of Business and Management Studies Master of Business AdministrationDocument15 pagesMakerere University College of Business and Management Studies Master of Business AdministrationDamulira DavidNo ratings yet

- Income Tax Guide UgandaDocument13 pagesIncome Tax Guide UgandaMoses LubangakeneNo ratings yet

- Accounting Rate of ReturnDocument3 pagesAccounting Rate of ReturnDeep Debnath100% (1)

- Chapter 5 - Globalization & SocietyDocument18 pagesChapter 5 - Globalization & SocietyAnonymous cwC8kTyNo ratings yet

- Net Present ValueDocument8 pagesNet Present ValueDagnachew Amare DagnachewNo ratings yet

- The Internal Environment Resources, Capabilities, and Core CompetenciesDocument41 pagesThe Internal Environment Resources, Capabilities, and Core CompetenciesMahmudur Rahman50% (4)

- Capital StructureDocument24 pagesCapital StructureSiddharth GautamNo ratings yet

- Investment Appraisal Techniques 2Document24 pagesInvestment Appraisal Techniques 2Jul 480wesh100% (1)

- Capital Budgeting FinalDocument78 pagesCapital Budgeting FinalHarnitNo ratings yet

- "Payback Period" Important in Capital Budgeting DecisionsDocument46 pages"Payback Period" Important in Capital Budgeting DecisionsNivesh Maheshwari88% (8)

- Risk and ReturnDocument31 pagesRisk and ReturnKhushbakht FarrukhNo ratings yet

- Buisness CycleDocument8 pagesBuisness CycleyagyatiwariNo ratings yet

- R30 Long Lived AssetsDocument33 pagesR30 Long Lived AssetsSiddhu Sai100% (1)

- Lesson: 7 Cost of CapitalDocument22 pagesLesson: 7 Cost of CapitalEshaan ChadhaNo ratings yet

- Taxation of Business IncomeDocument15 pagesTaxation of Business Incomekitderoger_391648570No ratings yet

- Introduction To Corporate GovernanceDocument26 pagesIntroduction To Corporate GovernanceLeah BallesterosNo ratings yet

- Time Value of MoneyDocument55 pagesTime Value of MoneySayoni GhoshNo ratings yet

- Case QuestionsDocument5 pagesCase QuestionsJohn Patrick Tolosa NavarroNo ratings yet

- Comparative Vs Competitive AdvantageDocument19 pagesComparative Vs Competitive AdvantageSuntari CakSoenNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Management-Module One Discussion - MandoDocument2 pagesPortfolio Management-Module One Discussion - MandoDavid Luko ChifwaloNo ratings yet

- Resume Journal A Study On Capital Budgeting Practices of Some Selected Companies in BangladeshDocument5 pagesResume Journal A Study On Capital Budgeting Practices of Some Selected Companies in Bangladeshfarah_pawestriNo ratings yet

- Financial Ratio AnalysisDocument4 pagesFinancial Ratio AnalysisJennineNo ratings yet

- Capital Structure Theories NotesDocument9 pagesCapital Structure Theories NotesSoumendra RoyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document5 pagesChapter 2Sundaramani SaranNo ratings yet

- Autocratic ModelDocument5 pagesAutocratic ModelVenkatesh KesavanNo ratings yet

- Long Term Sources of FinanceDocument26 pagesLong Term Sources of FinancemustafakarimNo ratings yet

- Chapter-17-LBO MergerDocument69 pagesChapter-17-LBO MergerSami Jatt0% (1)

- Session11 - Bond Analysis Structure and ContentsDocument18 pagesSession11 - Bond Analysis Structure and ContentsJoe Garcia100% (1)

- Cost ConceptsDocument24 pagesCost ConceptsAshish MathewNo ratings yet

- Accounting Dissertation Proposal-Example 1Document24 pagesAccounting Dissertation Proposal-Example 1idkolaNo ratings yet

- BIF Capital StructureDocument13 pagesBIF Capital Structuresagar_funkNo ratings yet

- 13corporate Social Responsibility in International BusinessDocument23 pages13corporate Social Responsibility in International BusinessShruti SharmaNo ratings yet

- Ethical Behaviour in Business PDFDocument2 pagesEthical Behaviour in Business PDFChanceNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 5.overview of Risk and ReturnDocument61 pagesCHAPTER 5.overview of Risk and ReturnDimple EstacioNo ratings yet

- Cost of CapitalDocument12 pagesCost of CapitalAbdii DhufeeraNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Credit ManagementDocument48 pagesIntroduction To Credit ManagementHakdog KaNo ratings yet

- Transfer PricingDocument37 pagesTransfer PricingVenn Bacus RabadonNo ratings yet

- Capital StructureDocument42 pagesCapital Structurevarsha raichalNo ratings yet

- Bond Yield and Price PDFDocument2 pagesBond Yield and Price PDFps12hayNo ratings yet

- Toyota Product RecallDocument1 pageToyota Product RecallJunegil FabularNo ratings yet

- Short Run Decision Making: Relevant CostingDocument47 pagesShort Run Decision Making: Relevant CostingSuptoNo ratings yet

- Forex - Problems in Exchange RateDocument26 pagesForex - Problems in Exchange Rateyawehnew23No ratings yet

- Mixed Cost High-Low Method ProblemDocument1 pageMixed Cost High-Low Method ProblemAnj HwanNo ratings yet

- Consolidated Financial StatementsDocument7 pagesConsolidated Financial StatementsParvez NahidNo ratings yet

- Responsibility Accounting and Transfer PricingDocument4 pagesResponsibility Accounting and Transfer PricingMerlita TuralbaNo ratings yet

- To Be An Observer in The Universe and Make A DifferenceDocument2 pagesTo Be An Observer in The Universe and Make A DifferenceShelly Mae SiguaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Finacial ManagementDocument25 pagesThe Role of Finacial Managementnitinvohra_capricorn100% (1)

- Analysis and Interpretation of FS-Part 1Document2 pagesAnalysis and Interpretation of FS-Part 1Rhea RamirezNo ratings yet

- Production TheoryDocument92 pagesProduction TheoryGoutam Reddy100% (3)

- Some Exercises On Capital Structure and Dividend PolicyDocument3 pagesSome Exercises On Capital Structure and Dividend PolicyAdi AliNo ratings yet

- Dividend PolicyDocument44 pagesDividend PolicyShahNawazNo ratings yet

- Differential Cost Analysis PDFDocument4 pagesDifferential Cost Analysis PDFVivienne Lei BolosNo ratings yet

- Leverage PPTDocument13 pagesLeverage PPTamdNo ratings yet

- ABC Costing Lecture NotesDocument12 pagesABC Costing Lecture NotesMickel AlexanderNo ratings yet

- Lesson 22 Capital Structure TheoriesDocument6 pagesLesson 22 Capital Structure TheoriesSana Ur Rehman100% (1)

- Interest Rates and Their Role in FinanceDocument17 pagesInterest Rates and Their Role in FinanceClyden Jaile RamirezNo ratings yet

- ADocument7 pagesATân NguyênNo ratings yet

- AssigmentDocument19 pagesAssigmentTân NguyênNo ratings yet

- Punjab Agricultural UniversityDocument6 pagesPunjab Agricultural UniversitySheetal NagpalNo ratings yet

- Ate Bec EssayDocument17 pagesAte Bec EssayMaria ClaraNo ratings yet

- Flexibility Business Performance P2.2Document23 pagesFlexibility Business Performance P2.2Kelly HermanNo ratings yet

- HNCD Business Unit Resource ListDocument52 pagesHNCD Business Unit Resource ListSwati RaghupatruniNo ratings yet

- HNCD Business Unit Resource ListDocument52 pagesHNCD Business Unit Resource ListSwati RaghupatruniNo ratings yet

- Questions-Training and Development ExamDocument9 pagesQuestions-Training and Development ExamKelly Herman100% (6)

- Contractual Liability and Tort Liability: Todea Al., Oroian I., L. HolonecDocument5 pagesContractual Liability and Tort Liability: Todea Al., Oroian I., L. HolonecMohammed Shah WasiimNo ratings yet

- Ch.12 - 13ed Fin Planning & ForecastingMasterDocument47 pagesCh.12 - 13ed Fin Planning & ForecastingMasterKelly HermanNo ratings yet

- Pearson BTEC Level 5 HND Diploma in Business Sample AssignmentDocument9 pagesPearson BTEC Level 5 HND Diploma in Business Sample AssignmentSanyam Tiwari50% (2)

- The Effects of IFRS Adoption On Taxation in NigeriDocument15 pagesThe Effects of IFRS Adoption On Taxation in NigeriJoseph OlugbamiNo ratings yet

- Name Suhail Abdul Rashid TankeDocument9 pagesName Suhail Abdul Rashid TankeIram ParkarNo ratings yet

- Cost Accounting 1 8 FinalDocument16 pagesCost Accounting 1 8 FinalAsdfghjkl LkjhgfdsaNo ratings yet

- Week 1-9 JSS3 AGRICDocument7 pagesWeek 1-9 JSS3 AGRICopeyemiquad123No ratings yet

- Annual Report - 2020 - Linde Bangladesh BOCDocument90 pagesAnnual Report - 2020 - Linde Bangladesh BOCAtiqul islamNo ratings yet

- IAS 16 PPE and IAS 40Document81 pagesIAS 16 PPE and IAS 40esulawyer2001No ratings yet

- Advanced Financial Management Test 1 May 2024 Solution 1701932012Document15 pagesAdvanced Financial Management Test 1 May 2024 Solution 1701932012shauryagupta20013007No ratings yet

- Assignment 2023 For BPOI - 105 (005) (DBPOFA Prog)Document1 pageAssignment 2023 For BPOI - 105 (005) (DBPOFA Prog)Pawar ComputerNo ratings yet

- Kotak Security Intenship ReportDocument34 pagesKotak Security Intenship ReportEk Deewana RajNo ratings yet

- Common Size Income StatementDocument7 pagesCommon Size Income StatementUSD 654No ratings yet

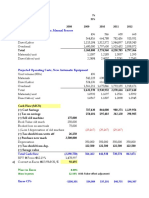

- Projected Operating Costs, Manual Process: Inflatio Mexico 7% Tax Rate 35%Document4 pagesProjected Operating Costs, Manual Process: Inflatio Mexico 7% Tax Rate 35%Cesar CameyNo ratings yet

- Ar 2010Document443 pagesAr 2010Dennis AngNo ratings yet

- Finance - WS2Document2 pagesFinance - WS2ElenaNo ratings yet

- Case Studies in Financial Management PDFDocument2 pagesCase Studies in Financial Management PDFGrand Overall100% (2)

- 3 Calculation of Daily Exchange PositionDocument10 pages3 Calculation of Daily Exchange PositionTalha AdilNo ratings yet

- BBA VI TH Sem Financial Institution & MarketsDocument2 pagesBBA VI TH Sem Financial Institution & MarketsJordan ThapaNo ratings yet

- WorkDocument52 pagesWorksara anjumNo ratings yet

- B Liquid Yield Option NoteDocument2 pagesB Liquid Yield Option NoteDanica BalinasNo ratings yet

- NUST Business School: Introduction To Operations Management - OTM 351 Assignment 3Document7 pagesNUST Business School: Introduction To Operations Management - OTM 351 Assignment 3Zainab AftabNo ratings yet

- Uts AKM IIIDocument2 pagesUts AKM IIISekar Wulan OktaviaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Audit Laporan KeuanganDocument20 pagesJurnal Audit Laporan KeuanganSalmiNo ratings yet

- Butler Excel Sheets (Group 2)Document11 pagesButler Excel Sheets (Group 2)Nathan ClarkinNo ratings yet

- Pfrs For Smes Full PFRS: Same Same Same SameDocument14 pagesPfrs For Smes Full PFRS: Same Same Same SameAnthon GarciaNo ratings yet

- BFD Test 1 With Solution Jun 2023 ST AcademyDocument10 pagesBFD Test 1 With Solution Jun 2023 ST AcademyHassan AzamNo ratings yet

- Course Pack For AgBus 174 Investment Management Module 1Document31 pagesCourse Pack For AgBus 174 Investment Management Module 1Mark Ramon MatugasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10Document13 pagesChapter 10Wasim Bin ArshadNo ratings yet

- DBB2104 Unit-08Document24 pagesDBB2104 Unit-08anamikarajendran441998No ratings yet

- Bram 2016Document270 pagesBram 2016Frederick SimanjuntakNo ratings yet

- Cost of Capital: Dr. A.N. SAHDocument41 pagesCost of Capital: Dr. A.N. SAHHARMANDEEP SINGHNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 Part A and Part B ReviewDocument9 pagesChapter 10 Part A and Part B ReviewNhi HoNo ratings yet