Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cash Vs Accrual

Uploaded by

kimringineOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cash Vs Accrual

Uploaded by

kimringineCopyright:

Available Formats

L-5386

(RM5-16)

11-00

Financial Management:

Cash vs. Accrual Accounting

Danny Klinefelter and Dean McCorkle*

Selecting a record-keeping system is an important decision for agricultural producers. The system should help with decision making in a risky environment and

calculate taxable income. Most producers keep their records with the cash

receipts and disbursements method or with an accrual method.

Either method should be acceptable for calculating taxable income (except for

corporate taxpayers who have revenues exceeding $25,000,000). However, it is not

acceptable to keep books throughout the year using one method of accounting and

then convert at year-end to another method, solely because the second method

might compute taxable income more favorably.

The main difference between accrual basis and cash basis accounting is the

time at which income and expenses are recognized and recorded. The cash basis

method generally recognizes income when cash is received and expenses when

cash is paid. The accrual method recognizes income when it is earned (the creation of assets such as accounts receivable) and expenses when they are incurred

(the creation of liabilities such as accounts payable).

Accrual accounting is more accurate in terms of net income because it matches

income with the expenses incurred to produce it. It is also more realistic for measuring business performance. A business can be going broke and still generate a

positive cash basis income for several years by building accounts payable (accruing but not paying expenses), selling assets, and not replacing capital assets as

they wear out.

However, most farmers and ranchers use cash basis accounting because: 1) they

do not understand the accounting principles that an accrual system requires;

2) given the cost of hiring accountants to keep their records, accrual accounting is

more expensive; and 3) cash basis accounting is more flexible for tax planning.

There is a process by which cash basis income and expense data can be adjusted to approximate accrual income. This can be very beneficial to producers.

The process has been recommended by the Farm Financial Standards

e

n

m

Task Force (FFSTF) which is made up of 50 farm financial experts

e

t

Edu

nag

a

c

from across the U.S. The only requirements for using this

at

M

i

k

o

process are accurate records of cash receipts and cash disburseis

ments for the period being analyzed, and complete balance

sheets (including accrual items) as of the beginning and end of

the period.

Getting the Best of Both Systems

The process yields an accrual adjusted, or approximate

accrual, income statement. It differs from accrual income in

that inventories may be valued at their current market value

rather

than their cost, and work in process (e.g., growing crops) is

valued by direct costs only (not including indirect labor and allocated

overhead).

The process for adjusting cash basis income to approximate accrual income is

outlined in Table 1. Beginning and Ending refer to information from the balance sheets as of the beginning and end of the accounting period.

*Professor and Extension Economist and Extension EconomistRisk Management, The Texas A&M University

System.

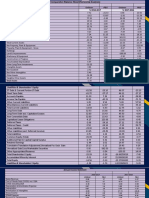

Table 1. Adjusting cash basis records to approximate accrual basis records.

Cash Basis

Cash receipts

Cash disbursements

Depreciation expense

Cash net income (pre-tax)

Cash income taxes and social

security (S.S.) taxes

Adjustments to Cash Basis

Beginning inventories

+ Ending inventories

Beginning accounts receivable

+ Ending accounts receivable

Beginning accounts payable

+ Ending accounts payable

Beginning accrued expenses

+ Ending accrued expenses

+ Beginning prepaid expenses

Ending prepaid expenses

+ Beginning unused supplies (fuel,

chemicals, etc.)

Ending unused supplies

+ Beginning investment in growing

crops

Ending investment in growing crops

No adjustment made (see Note 1)

Beginning income taxes and S.S.

taxes

+ Ending income taxes and S.S. taxes

payable

Beginning current portion of

deferred tax liability

+ Ending current portion of deferred

tax liability (see Note 2)

Cash net income (after-tax)

Equals Accrual Basis

Gross revenue

Operating expenses

Depreciation expense

Accrual adjusted net income

(pre-tax)

Accrual adjusted income taxes

and S.S. taxes

Accrual adjusted net income

(after-tax)

NOTE 1: Because depreciation is a noncash expense, technically it would not be reflected on a cash basis income statement.

Instead the statement would show the cash payments for property, facilities and equipment rather than allocating the cost

of the asset over its useful life. However, because the Internal Revenue Code requires capital assets to be depreciated, even

for cash basis taxpayers, the common practice is to record depreciation expense for both cash basis and accrual basis

income accounting.

NOTE 2: It is possible to have an income tax and social security tax receivable (refund due) or a deferred tax asset. In these

instances the signs (+/) of the period would be reversed when making the accrual adjustments.

In order to track the logic behind the cash-to

accrual adjustment process, consider the following example of a cash-to-accrual adjustment on

grain sales.

Table 2.

Cash receipts from grain sales this year

less:

Beginning grain inventory

(produced in prior year)

plus:

Ending grain inventory

(current year production not

sold yet)

equals: Accrual grain revenue

(approximate value of current

year production)

$150,000

$40,000

+$28,000

$138,000

Consider a second example of an expense

adjustment for accrued interest.

Table 3.

Cash disbursements for interest paid

this year

$36,000

less:

Beginning accrued interest

$9,000

(interest owed but not paid

in prior year)

plus:

Ending accrued interest (interest +$7,000

owed but not paid in current

year)

equals: Accrual interest expense

$34,000

(approximate cost of borrowed

funds in current year)

The same logic applies to the cash-to-accrual

adjustment for other accrual items. The rule to

remember when making the adjustment is that

an increase (beginning to ending) in an accrualtype asset item will cause net income to

increase, while an increase in an accrual-type

liability item will cause net income to decrease.

Review the example income statements for

Cash Grain Farms (Table 4) to see the differences between statements based on accrualadjusted information and statements based on

cash accounting.

Comparing Cash Basis to

Accrual-Adjusted Basis

Cash Grain Farms appears to be moderately

profitable on a cash basis. However, after adjusting the cash basis income statement to approximate an accrual basis income statement for the

same period, net income after tax increased

from $18,000 to $46,000. Because of the accrual

adjustments, gross revenues were greater by

$25,000 (from $175,000 to $200,000) while total

expenses were less by $19,000 (from $149,000 to

$130,000). However, because of the accrued and

deferred income taxes, the expense for income

taxes is increased by $16,000 (from $8,000 to

$24,000).

After making the accrual adjustments to the

income statement, Cash Grain Farms was shown

to be more profitable than had been portrayed

by the cash basis method of accounting. The

more critical situation would occur if the accrual-adjusted net income showed the business to

be less profitable than the producer may have

been led to believe by relying solely on cash

basis income statements.

As this illustration shows, computing income

on a cash basis can misrepresent true profitability for an accounting period when there is a time

lag between the exchange of goods and services

and the related cash receipt or cash disbursement. Such distortion can be substantially

reduced by also considering the net changes in

certain balance sheet accounts.

Table 4. Income statements: cash basis (left) and accrual-adjusted basis (right).

CASH GRAIN FARMS (Cash)

Year ending December 31

RECEIPTS

Cash grain sales

$150,000

Government program payments

$25,000

TOTAL CASH RECEIPTS

$175,000

EXPENSES

Cash operating expenses

Interest paid

TOTAL CASH EXPENSES

Depreciation*

TOTAL EXPENSES

Net farm income from operations

(cash basis)

Gain/loss on sale of farm capital assets

Net farm income, before tax

(cash basis)

Income taxes & S.S. taxes paid

NET FARM INCOME, AFTER TAX

(cash basis)

$85,000

$37,000

$122,000

$27,000

$149,000

$26,000

$

0

$26,000

$8,000

$18,000

CASH GRAIN FARMS (Accrual)

Year ending December 31

REVENUES

Cash receipts from grain sales

$150,000

Change in grain inventory

+$20,000

Government program payments

$25,000

Change in accounts receivable

+$5,000

GROSS REVENUES

$200,000

EXPENSES

Cash disbursements for operating

expenses

$85,000

Change in accounts payable

$12,000

+$1,000

Change in prepaid expenses

Change in unused supplies

$2,000

Change in investments in growing crops $4,000

Depreciation

$ 27,000

TOTAL OPERATING EXPENSES $95,000

Interest paid

Change in accrued interest

Accrual interest expense

TOTAL EXPENSES

Net farm income from operations

Gain/loss on sale of farm capital assets

Net farm income

*Remember, because the IRS requires capital assets

(machinery, equipment, buildings, etc.) to be depreciated over the useful life of the assets, the common

practice, even with cash basis accounting, is to

record a depreciation charge.

Income taxes & S.S. taxes paid

Change in income taxes & S.S. taxes

payable

Changes in current portion of

deferred taxes

Accrual income taxes & S.S. taxes

NET FARM INCOME AFTER TAX

(accrual basis)

$37,000

$2,000

$35,000

$130,000

$70,000

$

0

$70,000

$8,000

+$3,000

+$13,000

$24,000

$46,000

A quick way to convert the cash basis net

income of $18,000 to the accrual-adjusted

income of $46,000 is simply to add or subtract

the various net changes in inventories, accounts

receivable, accounts payable, and other noncash

transactions that affect the true profitability of

the operation. The net changes affecting the true

net income of Cash Grain Farms are shown in

Table 5.

Table 5. Net Changes in Non-cash

Transactions.

Beginning

Year

Inventories

Grain

Supplies

purchased

Investment in

growing crops

Accounts receivable

Prepaid expenses

Accounts payable

Accrued interest

Income taxes and

S.S. taxes payable

Current portion of

deferred tax

liability

End

Year

Net

Change

60,000

80,000

+20,000

8,000

10,000

+ 2,000

16,000

22,000

4,000

17,000

23,000

6,000

20,000

27,000

3,000

5,000

21,000

9,000

+ 4,000

+ 5,000

1,000

12,000

2,000

+3,000

21,000

34,000

+13,000

Table 6 presents a standard, simplified format

for converting a cash basis income statement to

an accrual-adjusted income statement using the

net changes in the balance sheet accounts. This

abbreviated format is useful if the objective of

the analysis is only to determine the approximate level of profitability after matching revenues with the expenses incurred to create the

revenues.

Table 6.

Cash Grain Farms

January 1 to December 31

Cash net farm income (after-tax)

Increase in inventory

Decrease in inventory

Increase in accounts receivable

Decrease in accounts receivable

Increase in prepaid expenses

Decrease in prepaid expenses

Decrease in accrued interest

Increase in accrued interest

Decrease in accounts payable

Increase in accounts payable

Decrease in income and S.S. taxes payable

Increase in income and S.S. taxes payable

Decrease in deferred tax liability

Increase in deferred tax liability

ACCRUAL ADJUSTED NET FARM

INCOME (after-tax)

$18,000

26,000

(

)*

5,000

(

)*

(1,000)*

2,000

(

)*

12,000

(

)*

(3,000)

(13,000)

$46,000

*The parentheses signify changes in the balance sheet

accounts that decrease true net income. These entries are

to be subtracted when calculating the accrual-adjusted net

income from cash basis net income.

In summary, an agricultural producer can

enjoy both the simplicity of cash basis accounting and the correctness of accrual accounting

by:

a. maintaining complete cash basis income

(receipts) and expense (disbursements)

records throughout the year;

b. preparing a complete balance sheet (including accrual items) at the beginning and end

of each year; and

c. then making the simple conversion of the

resulting cash basis net income to determine the accrual-adjusted net income.

Partial funding support has been provided by the Texas Wheat Producers Board, Texas Corn Producers Board,

Texas Farm Bureau and the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo.

Produced by Agricultural Communications, The Texas A&M University System

Extension publications can be found on the Web at: http://texaserc.tamu.edu

Educational programs of the Texas Agricultural Extension Service are open to all citizens without regard to race, color, sex, disability, religion, age or national origin.

Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension Work in Agriculture and Home Economics, Acts of Congress of May 8, 1914, as amended, and June 30, 1914, in

cooperation with the United States Department of Agriculture. Chester P. Fehlis, Deputy Director, Texas Agricultural Extension Service, The Texas A&M University

System.

1.5M, New

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Saratoga 05-06 Metric ListDocument38 pagesSaratoga 05-06 Metric Listluis_alberto_perez100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Table of Contents and Introduction to Working Capital ManagementDocument50 pagesTable of Contents and Introduction to Working Capital ManagementB Swaraj100% (1)

- B7AF102 Financial Accounting May 2023Document11 pagesB7AF102 Financial Accounting May 2023gerlaniamelgacoNo ratings yet

- Account ClassificationDocument2 pagesAccount ClassificationAzeemAkram100% (1)

- Ch13-Cash Flow STMDocument44 pagesCh13-Cash Flow STMAnonymous zXWxWmgZENo ratings yet

- Creative AgricultureDocument6 pagesCreative AgriculturekimringineNo ratings yet

- Cash Flow StatementDocument20 pagesCash Flow StatementKarthik Balaji100% (1)

- Company AccountsDocument116 pagesCompany AccountskimringineNo ratings yet

- Demand Factors That Influence Fin InclusionDocument23 pagesDemand Factors That Influence Fin InclusionkimringineNo ratings yet

- Financial ManagementDocument254 pagesFinancial Managementkimringine50% (2)

- The Financial and Economic Crisis of 2008-2009 and Developing CountriesDocument340 pagesThe Financial and Economic Crisis of 2008-2009 and Developing CountriesROWLAND PASARIBU100% (2)

- Company AccountsDocument116 pagesCompany AccountskimringineNo ratings yet

- Parity Conditions and Currency Forecasting-VVGG IllustrDocument36 pagesParity Conditions and Currency Forecasting-VVGG IllustrkimringineNo ratings yet

- Agribusiness Meaning, Nature and ScopeDocument5 pagesAgribusiness Meaning, Nature and ScopeAmarendra Pratap SinghNo ratings yet

- APT Lecture6Document48 pagesAPT Lecture6Pandit Ramakrishna AcharyaNo ratings yet

- Formal Verus Informal Finance Evidence From ChinaDocument68 pagesFormal Verus Informal Finance Evidence From ChinakimringineNo ratings yet

- International Tax StructuringDocument19 pagesInternational Tax StructuringkimringineNo ratings yet

- Audit Committee Quality and Agency TheoryDocument19 pagesAudit Committee Quality and Agency TheorykimringineNo ratings yet

- Financial Inclusion in AfricaDocument148 pagesFinancial Inclusion in AfricakimringineNo ratings yet

- Value Chain Vs Supply ChainDocument7 pagesValue Chain Vs Supply Chainsornapudi472No ratings yet

- Financial Ratio AnalysisDocument14 pagesFinancial Ratio AnalysisPrasanga WdzNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Formal and Informal Sector Interms of EmploymentDocument87 pagesRelationship Between Formal and Informal Sector Interms of EmploymentkimringineNo ratings yet

- Cost Volume Profit AnalysisDocument0 pagesCost Volume Profit Analysisprasathm873900No ratings yet

- Note On Financial Ratio FormulaDocument5 pagesNote On Financial Ratio FormulaRam MohanreddyNo ratings yet

- Geometric MeanDocument2 pagesGeometric Meanarchangel655No ratings yet

- Summary of Accounting ConceptsDocument21 pagesSummary of Accounting ConceptskimringineNo ratings yet

- Accounting For Incomplete Accounting RecordsDocument49 pagesAccounting For Incomplete Accounting RecordskimringineNo ratings yet

- CAP1 Finance Session 2 SlidesDocument41 pagesCAP1 Finance Session 2 SlideskimringineNo ratings yet

- Secondary MarketsDocument59 pagesSecondary MarketskimringineNo ratings yet

- Calculating Profit or Loss Under Incpmplete Records Scenario-GoodDocument7 pagesCalculating Profit or Loss Under Incpmplete Records Scenario-GoodkimringineNo ratings yet

- A Summary of Key Financial RatiosDocument4 pagesA Summary of Key Financial Ratiosroshan24No ratings yet

- Manufacturing-Accounts Teaching GuideDocument26 pagesManufacturing-Accounts Teaching GuidekimringineNo ratings yet

- Poor LiteracyDocument3 pagesPoor LiteracykimringineNo ratings yet

- PROPOSED BUDGET ESTIMATES For The Year Ending December 31, 2023 (Blue Book)Document565 pagesPROPOSED BUDGET ESTIMATES For The Year Ending December 31, 2023 (Blue Book)Thembinkosi BhonkwaneNo ratings yet

- Urban Design Assessment ReyesJanMerckM. 4BDocument17 pagesUrban Design Assessment ReyesJanMerckM. 4BREYES, JAN MERCK M.No ratings yet

- BharatearthDocument325 pagesBharatearthsravandskdNo ratings yet

- COM670 Chapter 5Document19 pagesCOM670 Chapter 5aakapsNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study On Cash Basis Accounting and AccrualDocument8 pagesComparative Study On Cash Basis Accounting and AccrualVardaan SuriNo ratings yet

- What Is Unearned Revenue?Document3 pagesWhat Is Unearned Revenue?JNo ratings yet

- Module 1.6 Forecasting Financial Statements Excercise ExcelDocument27 pagesModule 1.6 Forecasting Financial Statements Excercise Excelsachin kambhapuNo ratings yet

- Working Cap MGMT Questions SolutionDocument13 pagesWorking Cap MGMT Questions SolutionElin SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Ncert Solution Class 11 Accountancy Chapter 10Document68 pagesNcert Solution Class 11 Accountancy Chapter 10Prakal 444No ratings yet

- A) MSME QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesA) MSME QuestionnaireMd UmarNo ratings yet

- Final AccountsDocument65 pagesFinal AccountsAmit Mishra100% (1)

- Strong Core Solid GrowthDocument84 pagesStrong Core Solid GrowthValerie Joy Macatumbas Limbauan100% (1)

- Butwal Power Company Mature Stable BusinessDocument3 pagesButwal Power Company Mature Stable BusinessJenishNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2-Quiz DinglasanDocument4 pagesChapter 2-Quiz DinglasanAra AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Accounting For Merchandising Operations PDFDocument36 pagesChapter 5 Accounting For Merchandising Operations PDFJed Riel BalatanNo ratings yet

- Co-Investor Letter H1 2014 3Document9 pagesCo-Investor Letter H1 2014 3HoseNo ratings yet

- How to mass delete fixed assets in SAPDocument43 pagesHow to mass delete fixed assets in SAPNaveed ArshadNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Accounting Volume 2 Canadian 10th Edition Kieso Test BankDocument43 pagesIntermediate Accounting Volume 2 Canadian 10th Edition Kieso Test BankDarrylWoodsormni100% (13)

- Bingo Year 2009 FinancialsDocument472 pagesBingo Year 2009 FinancialsMike DeWineNo ratings yet

- Chapter 23 - Gripping IFRS ICAP 2008 (Solution of Graded Questions)Document29 pagesChapter 23 - Gripping IFRS ICAP 2008 (Solution of Graded Questions)Falah Ud Din SheryarNo ratings yet

- Unilever P&G Unilever P&G Assets: Add A Footer 1Document4 pagesUnilever P&G Unilever P&G Assets: Add A Footer 1Kathreen Aya ExcondeNo ratings yet

- Financial Statement Analysis - Shkelqim GerxhaliuDocument15 pagesFinancial Statement Analysis - Shkelqim GerxhaliuShkëlqim GërxhaliuNo ratings yet

- Alerion Annual Report 2022Document220 pagesAlerion Annual Report 2022Muhammad Uzair PanhwarNo ratings yet

- Accounts Receivables ManagementDocument7 pagesAccounts Receivables ManagementDipanjan DasNo ratings yet

- Revpro FlowDocument3 pagesRevpro FlowConrad Rodricks100% (1)