Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Introduction To The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in The Victorian Novel

Uploaded by

Pickering and ChattoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction To The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in The Victorian Novel

Uploaded by

Pickering and ChattoCopyright:

Available Formats

INTRODUCTION

We have heard a great deal lately about the New Woman. Why so little about the New

Man, who must inevitably accompany her?

Grant Allen, The New Man, 18941

Much is said at the present day on the subject of the New Woman But there exists

at the present day another body of social phenomena, quite as important, as radical, and if possible more far-reaching in its effects on the present and future, which

yet attracts little conscious attention or animadversion, though it makes itself everywhere felt Side by side with the New Woman in every society and in every class

in which she is found, stands the New Man!

Copyright

Olive Schreiner, Woman and Labour, 19112

The subject of this book is the radical New Man whose effects were everywhere

felt in late Victorian society. In examining this figure and his relationship with

the feminist New Woman my aim is in part to redress the silence to which Allen

and Schreiner refer and which has followed this figure into the twenty-first century. The New Man is best understood as the political ally to the New Woman,

supporting and aiding her attempts at social and political liberation; yet he is

also, in the fiction of the period, the New Womans romantic partner. Though

derided in the fin-de-sicle popular press, the New Man was imagined as a utopian figure by many New Women writers. Schreiner, who began writing Woman

and Labour while living in London in the 1880s, characterizes the New Man

as departing strongly from that of his forefathers in the direction of finding in

woman active companionship and co-operation rather than passive submission.3 Writers like Schreiner envisioned him as fostering, with the New Woman,

a progressive model of romantic partnership and as adopting an identity of compassion and healing.

This book, the first on the late Victorian New Man, argues that this figure presented ideological and narrative challenges for Victorian writers who sought to

incorporate him into their fiction: not only was his gentleness at odds with definitions of manliness based on professional competitiveness or physical strength,

794 New Man.indd 1

16/01/2015 15:07:41

The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in the Victorian Novel

but his inclusion in feminist narratives often re-established the romance plot

and so risked challenging the heroines desire for independence. In this way, he

was ill fitted for either the traditional Victorian marriage plot novel or the New

Woman bildungsroman. Although critics did not begin using the term New

Man until after the capitalized term New Woman was coined in 1894 in Sarah

Grands article, The New Aspect of the Woman Question, as well as Ouidas

response, The New Woman both in the North American Review this book

traces a lineage for the New Man that begins in the mid-Victorian period.4 Emergent conceptions of the gentleman, the public fascination with the Woman

Question and early feminist writing by figures such as Harriet Taylor Mill, John

Stuart Mill, Caroline Norton, Frances Power Cobbe and others encouraged

mid-century writers to envisage alternative models of masculinity that would

inform the later New Man. In the later century, a more clearly politicized version

of the New Man grew out of social purity movements, eugenic feminism and a

popular press intent on parodying the New Womans male companion.

Though the story of the New Man is less well known, the New Womans

emergence upon the literary and cultural scene of 1890s England is by now a

familiar one to Victorian critics and gender historians. The term was attached to

women who exhibited widely disparate feminist beliefs and degrees of activism:

the New Woman was a social purist, a woman who entered into free unions

or simply a professional working woman. By most accounts, she was an independent woman who argued for gender equality of some form and, along with

the dandy, boldly ushered in the sexual revolution of the 1890s. In the popular press, she was often depoliticized and represented by visual cues, frequently

depicted as a smoking, bloomer-wearing and bicycle-riding phenomenon. As

Sally Ledger notes, she was also often a fictional construct, a discursive response

to the activities of the late nineteenth-century womens movement.5 Just as the

New Woman was depicted in radically different ways a masculine, genderbending caricature, on the one hand, and a brave feminist challenging the sexual

double standard and the state of marriage, on the other the New Man was also

represented in highly contradictory ways in the late nineteenth century.

Popular publications like Punch depicted the New Man as the effeminate

and ridiculous partner of the manly and frightening New Woman, as I explain in

more detail later in the introduction. In contrast, New Women writers imagined

in earnest what kind of progressive man could be paired with the New Woman.

In Grands The New Aspect of the Woman Question, she is equally interested

in the lives of men and women. While she complains that man morally is in

his infancy, she also proclaims optimistically that the man of the future will

be better, while the woman will be stronger and wiser.6 Schreiner sees the New

Woman and New Man as forging a new culture together:

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 2

16/01/2015 15:07:41

Introduction

The New Man and Woman resemble two persons who start to climb a spur of the

same mountain from opposite sides; where, the higher they climb the nearer they

come to each other, being bound ultimately to meet at the top.7

It is this New Man, the man who attempts to build a new relationship with the

New Woman, that I explore in this book.

I focus on the ways in which novelists attempted to write the figure of the

New Man into their fiction, rather than discussing examples of actual New Men

who existed at the end of the Victorian period. In addition to examining New

Men in novels by late century authors such as Sarah Grand, Ella Hepworth

Dixon, George Gissing , Grant Allen and Olive Schreiner, I discuss the fiction

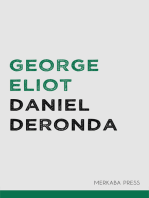

of Charles Dickens, Anne Bront and George Eliot. In these mid-century novels, Dickens, Bront and Eliot similarly craft characters that interrogate standard

masculinities. These early incarnations of the New Man might best be understood

as specific embodiments of the Victorian gentleman. These new gentlemen are

sensitive, nurturing and domestic men who attempt to build relationships with

their female partners that, while not exactly equal, value friendship and intellectual exchange in ways that predict the New Man and New Womans more radical

reformulation of romantic relations. In fin-de-sicle New Women fiction, the

New Man is a character that desires intellectual equality with the New Woman

and attempts, with varying degrees of success, to build a relationship freed from

the bonds of traditional gender models.

Fiction was an important site of ideological experimentation for the New

Woman. This was not just because fictionalized accounts of the New Woman

contributed to her mythology, as well as her actual materialization, but also

because they forced writers to consider how this figure challenged the Victorian

marriage plot, as well as social constructions of marriage more widely. The New

Man, too, presented a challenge to the traditional marriage plot novel; yet we

more often see the marriage plot challenging the New Man. That is, the New

Men that I identify are typically unsuccessful or periphery figures. Even in earlier

Victorian fiction, the most exemplary new gentlemen are often minor characters, separated from the confines of the principal marriage plot. For instance,

Dickenss most idealized New Men are not David Copperfield or Philip Pirrip,

but the secondary characters Tom Traddles and Herbert Pocket. And in George

Eliots Adam Bede (1859), Seth Bede presents such an extreme, even selfless,

model of compassionate masculinity that Eliot struggles to find a place for him

socially or domestically, situating him, like Dickenss Pip, as merely an observer

of a happy marriage.

By the late nineteenth century, the New Man more often takes centre stage

in New Women fiction. For instance, in Schreiners The Story of an African Farm

(1883), which I discuss in my final chapter, there are two possible New Men:

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 3

16/01/2015 15:07:41

The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in the Victorian Novel

Waldo, the New Woman Lyndalls gentle childhood companion, and Gregory

Rose, who disguises himself as a woman in order to nurse Lyndall. While Waldo

dies and Gregory enters an uninspired marriage in Schreiners novel, the tragedy

of the New Man is reversed in Amy Levys The Romance of a Shop (1888). Frank

Jermyn is an artist who marries one of the female protagonists, Lucy, a professional photographer; in a rare happy ending, they each carry on their own artistic

pursuits after their marriage. And in Mary Cholmondeleys Red Pottage (1899),

Hugh Scarlett and Dick Vernon are promising New Men who engage with the

intelligent New Women Rachel West and Hester Gresley. After Hugh dies, Dick

presumably immigrates with both women to Australia. Cholmondeleys ending

displays the typical machinations required of Victorian novelists who attempted

to accommodate the New Man into the marriage plot. In most late Victorian

novels, men abandon New Manhood for more conventional forms of masculinity, or the New Man extends the marriage contract to include other friends or

family members or, finally, he simply leaves England, like Hugh, unable to forge a

new relationship within the confines of British culture. These narratives portray

the later century New Man not so much as a minor character, but as a figure of

failure or compromise.

It was also common for late Victorian authors to write male characters that

experiment with New Manhood only to then reject a relationship with a New

Woman for a more socially or politically acceptable marriage. In doing so, these

writers typically imply that the choice of conventional marriage, indicative of

a happy ending just a few decades earlier, marks defeat for the fictional New

Man. Yet the New Mans failure to thrive in turn indicates a critique of restrictive gender identities and marital models. In The Queer Art of Failure (2011),

Judith Halberstam suggests that gender failure often means being relieved of

the pressure to measure up to patriarchal ideas and can thus present unexpected

pleasures.8 While late Victorian feminist writers did not often emphasize the

pleasures of gender failure, they did frequently note its necessity for social

progress. As I explain in more detail in the final chapter, Olive Schreiner in particular felt that what was deemed social failure was in fact part of a necessary

evolutionary struggle. In an 1886 letter to Karl Pearson, she writes, We want

to raise women And fail? Yes, fail, & in that action that seems a great

failure may lie a great success.9 Though the New Mans failure in these novels

does not always mark a great success, it does allow novelists to explore the pains

that result from restrictive social identities and institutions and to imagine the

successes that might one day follow individual failure.

This book thus details the way in which the New Man was at once a social

solution and a narrative problem for Victorian writers. On the one hand, imagining a man to be paired with the feminist New Woman was a way of envisioning

the future of feminism, one marked by reconciliation between the sexes. Further,

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 4

16/01/2015 15:07:41

Introduction

this term presented a useful model for Victorian men who were sympathetic

to the feminist movement and who did not identify with prominent masculine

models such as the dandy or the man of empire. On the other hand, writing the

New Man into the feminist quest plot risked dissipating the energies of rebellious heroines. As Jane Eldridge Miller explains, novelists writing about feminist

figures had difficulty concluding their narratives since they found that the

typical resolutions of Victorian novels impeded the representation of feminist

rebellion; conventional endings inevitably moved toward or endorsed stasis, the

status quo, and social integration through marriage, and thus ran contrary to the

heroines desire for independence, rebellion and social change.10 Few critics have

examined either the way that social changes in masculinity affected the marriage

plot, or how changing notions of marriage in turn affected masculine representation. It is a critical commonplace that the marriage plot is synonymous with the

womans plot, but the figure of the New Man demonstrates that the marriage

plot is also that of the man.11

This is not to diminish the fact that for Victorian women there was admittedly more at stake in the decision to marry since property, divorce and sexual

assault laws were openly biased towards men; it is however to suggest that by

ignoring the social and literary importance of romance and marriage in the narratives of mens lives, we risk re-inscribing outmoded masculine models and

public versus private divisions between the sexes. In 1999, historian John Tosh

insisted that the private [was] being reformulated to take account of men, in

the same way that the scope of the public [had] been progressively enlarged to

take account of women.12 Toshs work, specifically A Mans Place: Masculinity

and the Middle-Class Home in Victorian England (1999), was significant in presenting domesticity as an important facet of masculinity. Around the same time,

other influential works on Victorian masculinities emerged, including Herbert

Sussmans Victorian Masculinities: Manhood and Masculine Poetics in Early

Victorian Literature and Art (1995) and James Eli Adamss Dandies and Desert

Saints: Styles of Victorian Masculinity (1995), both of which examined the male

intellectual in early Victorian literature and culture. A key goal of Sussmans

study was to present early Victorian masculinity not as monolithic but as varied

and multiform,13 while Adams underscored the importance of masculinity as

a central problematic in literary and cultural change.14 These claims, thanks to

such work, are now largely taken for granted in the field of Victorian studies. In

the years since, important studies on Victorian fatherhood, male nursing, crossclass brotherhood, queer identities and male disability have enhanced the field

of Victorian masculinities.15 Such work has expanded our understanding of the

range of masculine models available to men, both fictional and historical, in the

nineteenth century.

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 5

16/01/2015 15:07:41

The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in the Victorian Novel

Masculinity is thus a key term for this book and, drawing from the work of

Sussman and others, I frequently use masculine rather than male to suggest the

constructed rather than the essentialist, the diverse rather than the monolithic

nature of these formations.16 While Adams referred to styles of masculinity,

I refer in this book to the New Man as a model of masculinity, a term that

incorporates the way in which this identity constitutes a type as well as an

ideal. Furthermore, in my focus on the domestic and private lives of fictional

Victorian men, I contend that models of masculinity and femininity are best

examined alongside one another, in agreement with critics such as Tosh and

Michael Roper who argue in the introduction to Manful Assertions that masculinity (like femininity) is a relational construct, incomprehensible apart from

the totality of gender relations.17 They suggest that women have been largely

absent from historical accounts of manliness, perhaps because of the assumption

that masculinity somehow takes on a sharper focus when women are removed,

as in the cases of all-male environments such as schools and clubs.18 Yet studies

that focus solely on men can only tell us so much about the development of

historical masculine models and the interaction between masculine and feminine social prescriptions. In contrast, studies that examine only the New Woman

can ignore the importance of the New Man to late century feminism. Certainly,

feminist literary critics in the 1970s and even 1980s had a more urgent need

to re-examine the treatment of female characters and women writers, who were

identified as oppressed or ignored. Feminist criticism, however, has offered critics the lexicon to examine masculinities, and examining the New Man within

that lexicon not only offers a richer picture of Victorian masculinities, but also

the demands and desires of the New Woman. Finally, while I focus primarily on

male characters, I acknowledge that models of masculinity and femininity may

be applied to female and male figures alike.

Early work on Victorian masculinities and revisions of New Women criticism appeared during the early to mid-1990s, and both offer reconsiderations

of earlier feminist work. Ann Ardiss New Women, New Novels: Feminism and

Early Modernism (1990) is an important example of the kind of critical work

done by New Women scholars in the 1990s and into the twenty-first century.

These critics aimed to modify earlier scholarship that disparaged the lack of

literariness in New Women novels. An oft-cited example of such earlier criticism is Elaine Showalters A Literature of their Own: British Women Novelists

from Bront to Lessing (1977), in which she argues pointedly that the feminists

were not important writers.19 She states that as New Women writers like Olive

Schreiner, George Egerton and Sarah Grand themselves often seem neurotic

and divided in their roles, less productive than earlier generations, and subject

to paralyzing psychosomatic illnesses, so their fiction seems to break down in

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 6

16/01/2015 15:07:41

Introduction

its form.20 However, critics like Ardis have shown that the New Woman novel

deserves a privileged place in the genealogy of Victorianism and modernism.

One of the most common complaints from earlier critics like Showalter was

that the New Woman novel was overly polemical and thus did not qualify as

real literature. Ardis rewrites the New Womans interest with politics as a conscious choice rather than a fault:

Insofar as they make frequent reference to extratextual circumstances, they resist

a readers efforts to extricate the literary artifact from history, and thereby from

politics. Because their authors choose not to view art as a sphere of cultural activity

separate from the realm of politics and history, these narratives refuse to be discrete.21

This kind of criticism opened up discussion not only of New Women writers as

legitimate, but also the figure of the New Woman herself, as can be seen by the

increase in New Woman scholarship since the early 1990s. This book argues,

if indirectly, that the proliferation of criticism on the New Woman facilitates

criticism on the New Man. I draw upon critics such as Ardis and Jane Eldridge

Miller when I argue that both the New Woman and New Man were important

figures in the transition between Victorianism and modernism, and, in fact, that

they relied on each other to conceptualize their individual gender codes. In the

remainder of this introduction, I look back to the mid-Victorian contexts that

set the stage for the emergence of the New Man in Victorian England, then map

the use of the term New Man in the 1890s and, finally, place him in the framework of masculinity studies more generally.

Copyright

Masculinity and the Mid-Century Gentleman

While the New Man as a term and concept was not fully developed until the end

of the century, this book begins by exploring mid-century fiction. That period

also witnessed radical reformulations of appropriate masculinity as a result of

emerging definitions of the gentleman and proto-feminist thinking voiced by

writers such as Frances Power Cobbe and Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon. In

fact, the notion of the ideal man as a figure that adopted a (female) standard of

sexual virtue and fostered a model of companionate marriage develops first in

the more conservative mid-Victorian period; for this reason, I begin with Dickenss David Copperfield (1850) and Great Expectations (1861), both important

fictional explorations of the Victorian gentleman.

The New Woman likewise did not suddenly appear fully formed in the

1890s. The Woman Question had been substantially debated throughout the

century, so rather than view the New Woman as emerging quite suddenly at the

fin de sicle, we can better understand her as a late century incarnation of a figure

that evolved, in part, from earlier debates on gender and womens roles in society.

794 New Man.indd 7

16/01/2015 15:07:41

The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in the Victorian Novel

For instance, Ella Hepworth Dixon suggested in 1899 that by penning Aurora

Leigh (1856), Elizabeth Barrett Browning undoubtedly proclaimed herself one

of the earliest of the new women.22 Just as Grand asked in 1898 whether terms

such as the human-question or humanity-question might be more appropriate

than the woman-question since the combined interests of men and women

cannot be separated, earlier Victorian writers were similarly aware that questions

about womens social role and future must necessarily affect men.23 The debates,

then, that would later evolve into attacks of, or defences for, the New Man and

New Woman began much earlier in the Victorian period.

The efforts of the early Victorian feminist movement focused largely on the

rights of the married woman since her position was, in legal terms, a powerless

one. She had no legal control over her property or earnings, no protection if her

husband chose not to give her adequate spending money and she had no legal right

to custody of her children. She furthermore had no way of obtaining a divorce,

unless by a private Act of Parliament: between 1670 and 1857 only four women

were actually successful in doing so.24 The notorious 1836 trial in which Caroline

Nortons husband accused her and Lord Melbourne, the Whig prime minister,

of adultery forced the British public to confront these legal imbalances. After a

difficult marriage with a husband who beat her and stole her earnings, Norton

left him, only to have him drag her into the press through the ordeal of a public

trial. Though Melbourne was exonerated, Norton could then not obtain a divorce

from her husband nor could she obtain custody of her own children. Her political

campaigning, however, led to the passing of the Custody of Infants Act of 1839.25

Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon also demanded legal changes in favour of womens

increased rights within marriage. Bodichon, feeling that John Stuart Mills 1848

Principles of Political Economy ignored discussions of marriage and divorce law,

published a political pamphlet of her own that remedied Mills omission: A Brief

Summary, in Plain Language, of the Most Important Laws of England Concerning

Women (1854).26 This was followed by the 1854, 1856 and 1857 parliamentary

debates about divorce and the Matrimonial Causes Act, which resulted in the

creation of an English divorce court in 1857. And although married women were

not given the right to own property until 1870 and, with further amendments,

1882, Parliament also debated married womens property in 1857.

These legal and social changes were not only brought about by committed or

radical feminists, as Ben Griffin has recently underscored, since their demands

had to be supported by Parliament and so were filtered through a complex web

of male beliefs, assumptions, and aspirations if the law were to be changed.27

One of the widespread cultural assumptions that Griffin emphasizes from this

period was the growing awareness that many men and not just working-class

men were physically or psychologically abusing their wives and that marriage and child custody laws gave men the power to do so.28 Elizabeth Foyster

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 8

16/01/2015 15:07:41

Introduction

has noted that while condemning domestic violence was not unique to the

Victorian period, there was indeed an increasing volume and range of complaints about male violence in marriage, which created the perception that such

abuse was on the rise.29 In the 1850s, John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor Mill

wrote a number of newspaper articles on shocking cases of domestic violence and

the lenient sentences given to male abusers. And in 1862, Frances Power Cobbe,

in an article entitled Celibacy vs. Marriage, admitted that the divorce court

had revealed secrets which must tend to modify immensely our ideas of English

domestic felicity.30 She asks, who imagined that the wives of English gentlemen

might be called on to endure from their husbands the violence and cruelty we

are accustomed to picture exercised only in the lowest lanes and courts of our cities?31 Of course, novelists like Dickens and the Bront sisters did in fact imagine

such cruelty earlier in the period. In my readings of their fiction, I show how

Dickenss home for homeless women and Anne Bronts novelistic comment on

the trials of an abused wife in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) can be seen as

responses to the larger cultural awareness and exposure of male abuse.

Another aspect of the widespread re-assessment of Victorian domestic ideology and the role of the English gentleman was the focus on male sexual discipline.

Sexual purity was a key factor in the development of the late century New Man

as New Women writers labelled degenerate any man who exploited the sexual

double standard. While the late Victorian social purity movement articulated

these issues on a grand scale, links between manliness and purity emerged in the

1850s. Middle-class men in fact received contradictory prescriptions concerning

sexuality. Though they were expected to discipline their natural sexual energy,

they were also expected to have gained experience before marriage. Sex was

considered a rite of passage for young men and repeated intercourse not only satisfied mens desires but was a form of display intended to impress other males.32

As John Tosh argues, it was this connection between sexual identity and reputation that Evangelicals attempted to curb; instead of relying on reputation to

prove manliness, they suggested, character should be emphasized as a valuable

model among young men.33 As I note in chapter one, Dickens hyperbolizes this

model of moral character and sexual abstinence with Tom Traddles; engaged

for many years before he has the resources to marry his fiance Sophy, his motto

Wait and Hope! imbues an otherwise unfortunate scenario with optimism.34

By the late century, writers like Gissing were less hopeful that men would be able

to withhold their sexual desires during lengthy engagements.35 Yet even Dickens,

whose heroes, according to Margaret Oliphant, are spotless in their thoughts,

their intentions, and wishes, admitted in a letter to Emerson that if his own son

were particularly chaste, he should be alarmed.36 Dickenss admission reveals the

contradictory ideals at work in fictional and historical masculinities as his novels

promote an ideal of male sexual discipline (or at the very least, avoid explicit

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 9

16/01/2015 15:07:41

10

The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in the Victorian Novel

discussion of possible relapses from such a regiment for his protagonists), even if

he realized the improbability of adhering to such an ideal.

Evangelical beliefs may have influenced the development of the gentleman,

but religious thought most strikingly intersected with Victorian masculinity

through the development of muscular Christianity, popularized by writers like

Thomas Hughes and Charles Kingsley. The term itself is typically attributed to

its use in an 1858 review of Hughess Tom Browns Schooldays (1857), in which

the critic emphasizes the great importance and value of animal spirits, physical

strength, and hearty enjoyment of all the pursuits and accomplishments which

are connected to them.37 Norman Vance, who prefers the term Christian manliness, notes that it represented a strategy on behalf of clergymen and writers

alike for commending Christian virtue by linking it with more interesting secular notions of moral and physical prowess.38 It embodied a kind of Christianity

which could be demonstrated to be manly and was associated with competitive sport.39 James Eli Adams notes that this regimen seems to mark a return to

aristocratic norms of masculinity, since the appreciation of the animal spirits

as related to both martial and sexual vigour called to mind the stereotype of the

Georgian rake.40 This understanding of muscular Christianity, as well as its associations with competition and public school education, marks it as distinct from

the model of the gentlemen that I discuss. Vance in fact distinguishes between

the moral gentlemanliness explored by writers like Dinah Mulock Craik and

Dickens, and the men in Kingsleys and Hughess fiction; in their writings,

the glory embedded in the long history of chivalry and gentlemanliness linger

seductively.41 The muscular Christian, then, is not a precursor to the New Man

but might rather be seen as an ancestor to the imperial pioneer developed in

male adventure fiction of the late century.

As Vances category of moral gentlemanliness implies, new understandings of the gentleman tended to emphasize the importance of moral integrity as

defining a man in the early Victorian period. As many critics have explained, the

impact of industrialism and the rise of the middle classes altered long-standing

associations between gentlemanliness and status in the mid-century. The passing

of older ideals of manliness thus marked the loss of a central point of identity

and social reference for large numbers of men and forced Victorians to renegotiate what it meant to be a gentleman.42 In his influential Self-Help (1859), Samuel

Smiles argues that the qualities of a True Gentleman depend not upon fashion

or manners, but upon moral worth not on personal possessions, but on personal qualities.43 The mid-century novels that I discuss emphasize strong moral

character as defining ideal masculinity, but they also offer a vision of the early

New Man that is distinctly middle class. Like the New Woman, the New Man,

as a model for the future of England, is most often aligned with the professional

or entrepreneurial classes.

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 10

16/01/2015 15:07:41

Introduction

11

Exactly what constituted moral worth for a middle-class man, and how

this translated into sexual or romantic behaviour, was debated in mid-Victorian

fiction. As Adams details, self-discipline became the defining feature of midVictorian manliness, a feature that, confusingly, could also be realized by women.

Drawing on Claudia Nelsons Boys Will Be Girls: The Feminine Ethic and British Childrens Fiction (1991), Adams suggests that in characters like Dobbin

from Thackerays Vanity Fair (18478), we can identify something of the moral

androgyny informing early-nineteenth century childrens literature, where

manly is an honorific term applied to boys and girls alike, as denoting moral

maturity generally.44 Similarly, Carol Christ has identified a feminine ideal

of male behaviour in mid-century writing by poets like Alfred Tennyson and

Coventry Patmore, one crystalized in Tennysons androgynous notion of manhood fused with female grace in In Memoriam (1850).45 Yet over the course

of the century, commentators would discriminate between masculine self-discipline and feminine self-denial, the one denoting aggressive self-mastery, the

other a surrender to external influences.46 The relative flexibility of these notions

in the mid-century, though, meant that novelists frequently crafted male characters that drew positive qualities from both gender models.

Accordingly, I analyse novels that articulate such reformations of masculine

behaviour. The mid-century novels I have chosen Charles Dickenss David

Copperfield and Great Expectations, Anne Bronts The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

and George Eliots Adam Bede promote early versions of the New Man. While

these novels offer particularly pointed critiques of aggressive masculinity and

unequal marriages, this is by no means a comprehensive list: fiction by Dinah

Mulock Craik, Elizabeth Gaskell, William Makepeace Thackeray, Anthony

Trollope, Charlotte Yonge and others contain male characters that emphasize

companionate marriage models and are presented as figures of healing rather

than aggression. In fact, Margaret Markwicks New Men in Trollopes Novels:

Rewriting the Victorian Male (2007) offers a reading of Trollopes male figures

as early New Men. What distinguishes our projects is that Markwick uses the

example of the New Man of the 1980s and 1990s, not the Victorian period, as

her model. She claims, The New Man, so heralded by our generation, is alive

and well in Trollopes novels, changing the nappies, making the gravy, pushing

the pram, hugging his sons and his daughters.47 The twentieth-century New

Man was largely a model of new fatherhood, while the Victorian New Man

was a model husband or lover; thus such differences in emphasis inform our

approaches to the New Man.48

These authors were all invested in the state of marriage and how it affected

both men and women in the mid-century. Kelly Hager, for instance, has argued

that the plots and politics of early Victorian feminist writings, such as those by

Caroline Norton, have much in common with those we find in Dickenss fiction.49

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 11

16/01/2015 15:07:41

12

The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in the Victorian Novel

David Copperfield, she suggests, is concerned in a multiplicity of ways with the

institution of marriage and the miseries it causes.50 Furthermore, these mid-Victorian novels anticipate New Woman fiction in their depiction of female characters

that endure abusive relationships, struggle between reason and romantic passion

and search for a vocation of their own. Tenant and Adam Bede in particular map

their heroines desires for a vocation and reluctance to marry. The novelists pair

these struggling women with protoNew Men, anxious to understand them,

comfort them and, to borrow the words of Mona Caird from later in the century,

contemplate a relationship between the sexes which is more close and sympathetic than the world has yet seen.51

Olive Schreiner in fact hailed Eliots Maggie Tulliver as the finest portrait of

a womans soul that ever was painted, and she praised Dickenss realistic representations of Victorian life.52 Though many late century writers emphasized the

way in which their fiction constitutes a clear break with mid-Victorian fiction

and narrative techniques, Schreiners comments suggest that fin-de-sicle authors

were aware of their indebtedness to earlier fiction. There are numerous examples of late century metafictional engagements with earlier Victorian writers and

texts. For instance, in The Type-Writer Girl (1897), Allens writer-heroine explicitly references authors like Charlotte Bront and Elizabeth Barrett Browning ,

and in The Story of a Modern Woman (1894), Dixons Mary Erle reads David

Copperfield and evaluates Steerforths behaviour towards Little Emily. Late

Victorian authors, furthermore, looked to many of these earlier writers as themselves early embodiments of the New Man and New Woman. In her Recollections

of a Literary Life (1852), Mary Russell Mitford described the Brownings in

terms that would continue to characterize them later in the century: Married

poets! Charming words are these, significant of congenial gifts, congenial labour,

congenial tastes.53 Carlyle categorized their relationship as a life-partnership.54

And Allens Juliet attempts to cultivate such a relationship with her New Man

and writing partner, Mr Blank.

Indeed, many incarnations of the New Man and New Woman later in the

century situate them as writers or artists, ideally working alongside one another.

The marriage between Harriet Taylor Mill and John Stuart Mill was another

example of such an historical ideal. In The Subjection of Women, Mill compares

the marital union to a business partnership in order to argue that men need not

master their wives:

Copyright

It is not true that in all voluntary association between two people, one of them must

be absolute master: still less that the law must determine which of them it shall be.

The most frequent case of voluntary association, next to marriage, is partnership in

business: and it is not found or thought necessary to enact that in every partnership,

one partner shall have entire control over the concern, and the others shall be bound

to obey his orders.55

794 New Man.indd 12

16/01/2015 15:07:42

Introduction

13

This construction of marriage as a voluntary association and a partnership,

though not reliant on romantic or passionate language, in many ways predicts

the late century New Woman and New Man. Even though by the 1880s and

1890s, men and women were much closer to realizing such a union, the sad state

of marriage remained a keynote of the feminist movement. The public response

to Mona Cairds essay Marriage, published in the Westminster Review in 1888,

is a striking example of this ongoing concern. The Daily Telegraph, stirred by

Cairds claim that marriage was a vexatious failure, ran a column entitled Is

Marriage a Failure? for which they notoriously received over 27,000 letters in

response.56

The New Man at the Fin de sicle

A defining feature of the New Woman was her critical attitude towards male

promiscuity and the state of marriage. The New Woman was commonly misinterpreted to suggest either that, given her critical view of marriage, she voluntarily

entered into free unions with willing men, or that she opposed marriage altogether. While true of some women, both fictional and historical, this aspect of the

New Woman was exaggerated and manipulated by the popular press and encouraged by the release of Grant Allens scandalous and widely popular The Woman

Who Did (1895).57 Most New Women, in fact, did not simply equate womens

liberation with sexual liberation and many, like Sarah Grand, actually considered

themselves to be social purists. Social purists did not argue for the dissolution of

marriage but demanded that husbands refrain from extramarital sex and wives be

treated equally and with respect; they thus encouraged men to adapt to the sexual

models of women, just as Evangelicals did in the mid-Victorian period.

Indeed, an important cultural event in the histories of both feminism and male

sexuality was the work of social purists, led by Josephine Butler, to repeal the Contagious Diseases Acts of the 1860s, a goal that was ultimately achieved in 1886.

As I explain in chapter three, these acts were motivated by public anxiety relating

to prostitution and the spread of venereal disease, particularly amongst the army

and navy. The acts maintained that any woman suspected of being a prostitute

could be forced to undergo medical examination. They therefore reflected the

social belief that a womans body served as the site where a contaminating sexuality becomes visible.58 Social purists argued, instead, that it was male sexuality

that needed controlling, and the male body that was responsible for social degeneration.59 They adopted nationalistic rhetoric by contending that deviant male

sexuality was not only a threat to individual marriages but to the entire nation.

Grand, in The Man of the Moment (1894) a key text in the debate on late

Victorian masculinity claims that the New Womans ideal of a husband is a

man whom she can reverence and respect especially in regard to his relations

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 13

16/01/2015 15:07:42

14

The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in the Victorian Novel

with her own sex.60 She moves from considering the importance of the marital

union to the larger, social implications of mens sexual behaviour:

Philosophers show that the stability of nations depends practically upon ethics.

When they do not aspire to be as perfect as they know how to be, they collapse.

The man of the moment does anything but aspire, and it is the low moral tone which

he cultivates that threatens to enervate the race.61

With her claim that negative male morality would weaken the British race,

Grand points to the process of degeneration, a notion that became a pervasive

fear in the late nineteenth century.62 Fears of degeneration were associated with

the emerging science of eugenics, which aimed to improve the race by encouraging fitter reproductive pairings and discouraging others deemed unfit.63

The emergence of eugenic feminism, whose proponents labelled sexually deviant men unfit for procreation, emphasized how important it was for women to

choose a healthy male partner rationally by replacing passion with sexual selection.64 In fact, many late Victorian novels refer to male figures as specimens,

thus emphasizing that the male body was understood as a site for examination,

a new cultural phenomenon likely stemming from the feminist scrutiny following the repeal of C. D. Acts, as well as the emergence of the relatively new

fields of sexology and anthropology.65 Such scrutiny had racial implications:

indeed, the New Man is largely a model of English masculinity, with the associations of racial purity and imperialism that this categorization implies. Earlier in

the period, Dickens contrasts his English characters Tom Traddles and David

Copperfield with the racialized Uriah Heep, while late century novelists like

Sarah Grand distinguish the New Man from French dandies.

Debates such as that over the C. D. Acts and the rise of eugenic feminism thus

set the stage for the emergence of the New Man in the 1890s. In 1894, Reynell

Upham declared, The world is growing old, they say; but if it can produce the

new woman it can, and will, bring the New Man upon the scene.66 And Emma

Churchman Hewitt asked in 1897, While woman has become new, does man

fancy that he has remained at a standstill?67 While the New Man was largely

figured as a romantic partner for the New Woman, Hewitt also imagines him as a

new father, insisting that [g]oing out into the world and earning a living for herself and others, no more makes woman masculine, than does helping his wife with

the care of the children, effeminate man.68 Although the term New Man was not

as widely used as the New Woman, a number of periodicals, such as Punch, called

attention to the New Man in satirical cartoons, stories and polemical articles. In

1894 and 1895, at the height of cultural discussions of the New Woman, Punch

released a series of illustrations depicting New Women with diminutive and powerless New Men, thus showcasing this figure as a type to avoid.

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 14

16/01/2015 15:07:42

Introduction

15

Punchs New Man is an effeminate character that allowed misogynistic writers and illustrators to criticize both New Women and effeminate men in one

strike. That is, this figure which might also be understood as an antiNew

Man indeed draws attention to the masculine nature of the New Woman, but

he also emphasizes her male companion as small, weak and dandyish. Indeed,

the dandy and the New Woman were often linked in the periodical presses of the

fin de sicle as figures that provoked fears over the malleability or disappearance

of gender distinctions. This is in contrast to late century feminist responses to

masculinity, which offset the dandy against the ideal of the New Man, as I outline in my later chapters. Many of the illustrations in Punch show how cultural

anxieties about gender distinctions provoked defensive backlashes. For example, a drawing that appeared on 24 February 1894, with the foreboding title,

What It Will Soon Come To, shows a large woman attempting to carry the

bag of the small gentleman walking beside her.69 Similarly, in a drawing from 6

October 1894 (Weve Not Come to That Yet), a New Woman asks a gentleman

what he has changed his name to after marriage.70 The ominous titles suggest

that conservative commentators, despite their humour, were anxious about the

future of gender relations. Furthermore, these drawings imply that men should

be careful as to what kind of women they choose for their romantic partners.

This is indicated in another illustration, What the New Woman Will Make of

the New Man! (27 July 1895), which shows three New Women insisting that

their New Men wait patiently for them under the door of the dancehall.71 While

this last drawing is the only one that makes explicit reference to the capitalized

term New Man, the earlier images similarly imply that men who associate with

New Women risk ridicule.

In May 1894, Punch published A Ballade of New Manhood, a response to

Grands The Man of the Moment. For Grand, the man of the moment is so

called because he cannot continue unchanged on into the brighter and the better day which we are approaching.72 Her complaints are lengthy: the man of the

moment is immoral, weak willed and, worst of all, he is not sufficiently aware

of his own imperfections to do much for himself .73 Women, she claims, must

come to the rescue. If they cannot save the current generation, then they must

look to the next generation, which is to have proper principles spanked into it in

the nursery.74 In turn, Punchs Ballade warned its male readers that It appears

theyll be taken in hand / By the New Womanhood, that pursues / The programme of grim Madame Grand!75 The writer explains:

Copyright

Poor youths! At an imminent date

All the foibles of man theyre to lose;

If one ventures to lie in bed late,

Or latchkeys and language to use,

Or play penny nap, or amuse

794 New Man.indd 15

16/01/2015 15:07:42

16

The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in the Victorian Novel

His weak wits with aught else that is banned,

Hell be spanked till for pardon he sues

Tis the fiat of firm Madame Grand!76

But, Punchs readers could take some consolation in the fact that To reform

each grown-up reprobate / Is too hard and so we men will go on as we choose.77

The poem ends by asking Mr. Punch to spread through the length of the land /

Your decided dissent from the views, / And the plans of severe Sarah Grand!78

Mr. Punch, then, must act as a dissenting force against Grands project to promote and encourage the birth of the New Man. This passage makes explicit

Punchs resistance to the New Womans project and her hope to reform male

immorality. However playful, it is nonetheless a call to arms for its male readers,

aiming as it does to mobilize an anti-feminist (or least anti-Grand) response.

Before the New Man has even been fixed in the cultural imaginary, the author,

called only an unregenerate male, already encourages his male readers to resist

the temptations of New Manhood.79

In fact, a number of publications surfaced at this time in response to Grands

vitriolic language in The Man of the Moment. In an article called Madame

Sarah Grand and the New Man in the New Zealand newspaper Star, the writer

suggests that Grand has now turned her attention to the New Man, which

may either mean the new view taken of men by advanced women or actually

a new sort of grown-up male baby.80 And H.D. Traill in the Graphic explains

that Grand, in The Man of the Moment, gives readers a sketch of the wretched

makeshift and apology for male humanity whom the N.M., when he comes, will

supersede.81 While these authors are largely critical of Grands hyperbolic claims

about modern masculinity, their explicit engagement with the New Man, and

clear use of that term, might have in fact furthered the feminist aims of imagining this figure and presenting him as a real possibility.

Anti-feminist writers were not simply content to respond to Grand and

other feminist commentators: they also wrote mockNew Man stories. In October 1894, Punch published a story entitled The New Man (A Fragment from

the Romance of the Near Future). This melodramatic story describes a lonely

husband waiting at home with dinner while his wife enjoys herself at the club.

He puts a cloth over her dinner, knowing, however, that the meat would be

disregarded, and only the brandy and soda-water touched by the expected one.82

As with Punchs satirical cartoons, the author plays with gender reversals. Tears

come to the New Mans eyes as he remembers their wedding and honeymoon,

and he sadly recalls the anxiety of Alice to get back to town, to be off in the

City.83 In order to pass the time before her arrival, he picks up a New Man

novel. Substituting the New Woman for the New Man, it relates the adventures

of a wild, thoughtless man who was setting the laws of society at open defiance;

his response is, How can men write of men like this?84 The vignette ends with

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 16

16/01/2015 15:07:42

Introduction

17

the husband bursting into tears as his wife returns home in the early morning,

disregarding her attentive husband.85 The gender reversals here are clearly meant

to appear ridiculous and like the Punch illustrations, it gestures to an apparently

frightening future in which men, if not careful, could lose their identities as men.

The Speaker published a similar story that same year, also a gender-bending

vision of the future called simply The New Man. It features an effeminate New

Man who stays home to write about fashion, while his New Woman partner

is employed as a politician. The story opens in an overwrought satirical tone,

parodying Wildes depiction of Lord Henry Wotton in the opening paragraphs

of The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890):

In an exquisitely appointed boudoir a young man of pallid aspect was stretched on

luxurious cushions of a delicate mauve tint, with one emaciated hand limply holding a

blue pencil while the other was stretched over and anon in quest of a gold vinaigrette,

which he applied to his diaphanous nostrils.86

The New Woman enters the scene wearing a bicycle costume, which set off

admirably the muscular suppleness of her figure, and she wore, moreover, an air

of decision as of one who bears the heritage of a ruling sex.87 In both of these

tales of the future, the New Man is worthy of ridicule via his placement in the

domestic realm and his emotionality. Further, the Speakers fashion reporter

could also be a veiled reference to Wilde himself, who was editor of the Womans World magazine from 18879, a periodical that concentrated on fashion

and trends amongst Londons high society. The story again implies that, in this

alarming vision of the future, the only man who is an appropriate match for

the New Woman is the dandy. Or, as anti-feminist writer Eliza Lynn Linton

wrote in 1892, The truth is simply this the unsexed woman pleases the unsexed

man.88 Again, though, I want to suggest that these campaigns in the periodical

press against the New Man actually helped bring this concept into the cultural

imaginary of the late nineteenth century. Though the version of the New Man

that they promoted was ridiculous, foppish and weak, it nonetheless contributed to late century debates about feminism and how men would respond to the

changes that had so profoundly affected womens lives.

Furthermore, such writing also prompted questions about how the New Man

would materialize in late century fiction. At the end of his article, H.D. Traill,

for instance, asks whether Grand will now wave her wand in a three-volume

novel and let the New Man that Fairy Prince of our social future appear?89

And in fact, she does so with the depiction of Arthur Brock in her 1897 novel

The Beth Book. Novels were of course an important ideological testing ground

for the emergent figures of the New Woman and New Man, as Traill and others

recognized. In The Man of the Moment, Grand notes that as a candidate for

marriage he [the New Man] is the more interesting of the two perhaps, because

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 17

16/01/2015 15:07:42

18

The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in the Victorian Novel

he is not so well known. Woman is always being exhibited as maid, wife, widow,

and mother-in-law; but man for the most part is taken for granted.90 Many late

century novelists used the marriage plot novel to tease out what a new marriage

or sexual relationship might look like. This is not to suggest that other literary

forms especially the short story were not adopted and transformed by New

Women writers in important ways.91 But in their use of the novel, late century

writers self-consciously rewrote the marriage plots that had dictated the form

for much of the nineteenth century and attempted though admittedly with

varying degrees of success to make room for the New Man.

The late century novels that I discuss Ella Hepworth Dixons The Story

of a Modern Woman, Sarah Grands The Beth Book, George Gissings The Odd

Women (1893), Grant Allens The Type-Writer Girl, Olive Schreiners The Story

of an African Farm and Trooper Peter Halket of Mashonaland (1897) and, briefly

in the conclusion, Victoria Crosss Anna Lombard (1901) and Schreiners From

Man to Man (1926) all offer explicit engagements with the New Man, as well

as those less desirable masculine models that writers like Grand described in their

polemical articles. They can all be classified as New Woman novels, though they

offer varying degrees of sincerity and political engagement, and they all stage a

conflict between the New Womans quest narrative and her romance plot. The

New Man is often set up in opposition with the New Womans need for professional fulfilment, but his own journey to happiness is equally vexed. These works

similarly relate how the New Man must forge his own path and his own model

of masculinity ; although he is in the company of the New Woman, he is most

often depicted as lacking a community of like-minded, pro-feminist men with

whom to engage. And while the New Woman must often decide whether to

follow a romantic or professional path, the New Mans conflict is typically what

kind of woman to choose for a partner and whether he will thus remain a New

Man or retreat to more conventional, well-worn models of masculine behaviour.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of authors who crafted fictional New Men.

A longer list might include novels by Emma Frances Brooke, Mona Caird, Mary

Cholmondeley, Mnie Muriel Dowie, George Egerton, Thomas Hardy, George

Moore, George Meredith and others. I hope that this book will encourage

examinations of the New Man in works by lesser-known New Women writers in

particular, many of which remain understudied.

Copyright

Gentle Men and Masculinity Studies

In addition to arguing for continuities between conceptions of femininity and

masculinity, I want to emphasize the importance of devoting more critical and

theoretical space to exploring models of gentle, healing and compassionate masculinity. This book is an attempt to do so. The steadily growing field of Victorian

794 New Man.indd 18

16/01/2015 15:07:42

Introduction

19

masculinities has largely examined models of deviance and desire. This book

shares with such studies the theoretical assumption that masculinity is a complex

construct and not an unchanging or essential notion, but it avoids the claim that

masculinity is always in crisis. Instead, it shows that while Victorian novelists

reflect and even enact certain social anxieties in their fiction, they also attempt

to work through and reconcile these concerns; this suggests less an environment

of crisis than one of negotiation. In her introduction to Masculinity Studies and

Feminist Theory, Judith Kegan Gardiner expresses resistance to the talk of crisis, with its deliberate exaggerations and fomenting of anxieties, [which] echoes

the rhetoric of advertising and extends into academic feminism and masculinity

studies.92 Indeed, as she claims, it seems implausible that men, everywhere visibly in power, are in crisis.93

While it is useful to understand perceived crises in masculinity as moments

in which the contradiction between lived experience and ideals are exposed in

popular culture, I resist discussing the rise of the New Man, and the critical backlash that ensued, as a moment of crisis. This terminology, as Gardiner and others

have suggested, implies that there was once a period in history in which stable or

uncomplicated masculinity existed.94 This nostalgic mode of thinking is, at best,

inaccurate and, at worst, misogynistic and harmful. Further, the very term crisis

is so often linked in contemporary culture to political, economic and military

catastrophes that it seems an inaccurate term to apply to cultural shifts or periods of transition in the representation of gender models. Robert Griswold, in an

essay on divorce and Victorian manhood, suggests that a war of sorts was waged

over male identity in the nineteenth century, a war that focused on temperance,

sexual purity, and religious campaigns.95 While such campaigns certainly took

place, scholars within masculinity studies might do well to resist the language

of war, conflict and combat, and instead (or in addition) show how changes in

masculinity were marked by consolidation and compromise. Abraham Fuks has

noted that todays media is similarly filled with discussions about the crisis in

medicine and that medical language is infused with the language of war, as we

fight outbreaks, speak of the war on cancer and take doctors orders.96 One of

the dangers of this, he suggests, is that the disease supplants the patient, who

becomes the metaphorical battlefield.97 Within talk of a crisis of masculinity,

the battleground set up is that between men versus women, and old versus new

masculine models. The nuances between such groups are obscured in declarations of war and, of course, the very language of war prescribes a specific model

of disciplined, martial masculinity.

Admittedly, however, notions of compromise are often less theoretically

compelling than conflict. Indeed, deviant male characters have traditionally

been more interesting to scholars than those figures that embody gentler models

of masculinity. Yet by attending to both harmful and constructive models, and

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 19

16/01/2015 15:07:42

20

The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in the Victorian Novel

by reorienting our critical understandings away from crisis and towards negotiation, we can obtain a much more comprehensive understanding of masculinity,

both in the Victorian period and beyond. I do examine models of deviant masculinity in this book, but by also foregrounding the figure of the New Man, I

emphasize the way in which Victorian writers imagined progressive masculine

models, alongside those more dangerous or aggressive men.

Throughout the book, I continue to return to the point that the New Man

was a challenging character for novelists to incorporate into their fiction and for

the late Victorians to fully imagine. He remained, even by the 1890s, a figure of

the future, a kind of utopian model that was difficult to achieve. Gardiner has

argued that:

Masculinity is a nostalgic formation, always missing, lost, or about to be lost, its ideal

form located in a past that advances with each generation in order to recede just

beyond its grasp. Its myth is that effacing new forms can restore a natural, original

male grounding. Feminism, in contrast, is a utopian discourse of an ideal future, never

yet attained.98

The New Man both confirms and throws into question such assumptions. He

is pointedly not a model of nostalgic masculinity, incorporating instead part of

feminisms utopian discourse of an ideal future. Yet the difficulty of achieving

New Manhood within a patriarchal society meant that this figure also served to

emphasize the temptations of nostalgic, supposedly natural masculinity. Again,

this means that in fiction, New Men were often presented as failures or were

minor characters. Yet their peripheral status points to other stories worth exploring, supporting Alex Wolochs claim that novelists often think alternative, or

future, stories through a secondary character.99 The New Man, like the New

Woman, gestures to these alternative futures.

Chapter one examines Dickenss range of moral gentlemen in David Copperfield and Great Expectations. In David Copperfield, James Steerforth, Uriah

Heep and Tom Traddles are presented as possible models of masculinity for

David; these characters allow him to evaluate the rewards and pitfalls of differing masculine ideals. Davids emphasis on Heeps difference, represented by his

grotesque physique and sexuality, serves not only to other this strange man,

but also to racialize him. Towards this end, I argue that Heep can be aligned

with Victorian anti-Semitic representations of the Jew and that he becomes the

novels ultimate scapegoat figure. Steerforth too links economic and social deviance with sexual deviance, exemplified most strikingly in his careless treatment

of Little Emily.

They are presented in contrast to Traddless sexual constancy and compassion, which qualities render him a positive model of middle-class masculinity

for David. These qualities, Dickens shows, are indebted to feminine virtues;

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 20

16/01/2015 15:07:42

Introduction

21

just as Traddles adopts a female-influenced model of sexual virtue, David must

live up to the imagined moral precepts of his shadow sister, Betsey Trotwood

Copperfield, a character whom his aunt invents but whose effects reverberate

throughout the novel. The chapter ends by suggesting that Herbert Pocket in

Great Expectations troubles the relationship between the Dickensian gentleman

and his middle-class professional status. Though his gentleness makes him an

ideal husband, it is at odds with a demanding market economy; Dickens thus

implies that the route to gentlemanliness and protoNew Manhood is not

always clearly mapped or easily achievable for the mid-Victorian man.

From Dickens, I move to a consideration of male healing in Bronts The

Tenant of Wildfell Hall and Eliots Adam Bede. Various critics have noted that

these novels are unsatisfying as narratives of female vocation: Helen gives up

painting, while Dinah abandons her preaching and both ultimately enter familiar-looking marriages. Yet if we regard these novels as narratives of reparative

masculinity, we can draw more hopeful conclusions. I show how Bront and

Eliot value a masculinity associated with healing and that these qualities, even

if not fully attained by the male characters at the novels conclusions, project an

early vision of the New Man. The characters Adam Bede and Gilbert Markham

emerge as imperfect but nonetheless heroic gentlemen, who must learn to subdue their aggression in favour of tenderness. They are contrasted with Arthur

Donnithorne and Arthur Huntington, both of whom are marked as dangerous

masculine models due to their cruel treatment of women. Finally, I suggest that

the sidelined siblings, Frederick Lawrence and Seth Bede, may be considered

positive, alternative models in the novels as they temper the main figures tendencies towards possessiveness and aggression. In particular, I emphasize the way

in which Seths benevolent, nearly masochistic, masculinity challenges the very

boundaries of conventional masculine identity and the marriage plot.

The next chapter reads two New Women novels in the context of late century

experiments with the marriage plot. A literary project that involved many New

Women writers was the attempt to update the realism of the earlier Victorian

novel by rewriting the male hero and the marriage plot. Analysing Dixons The

Story of a Modern Woman and Grands The Beth Book, this chapter demonstrates

how the modern villains in these novels occupy culturally charged professions

of the fin de sicle. In their insistence that the public lives of men in particular

those of doctors, politicians and the press influence the private lives of women,

Grand and Dixon imply that the New Man cannot simply be the romantic partner to the New Woman but must be her political ally in the public sphere as

well. The novels critique the power afforded to these figures, and the physician in

particular is read as a dangerous enemy of the New Woman: reworking the focus

on masculine healing that I earlier discuss, Dixon and Grand in turn emphasize how the doctor could be linked ironically to social disease and patriarchal

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 21

16/01/2015 15:07:42

22

The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in the Victorian Novel

control. Their desire to update the Victorian novel also involves imagining the

New Man: while Dixon evades the courtship plot as her heroine Mary chooses

female solidarity over romance, Grand presents, in the character of the American

artist Arthur Brock, a unique solution to New Manhood and the marital ending.

The fourth chapter locates a narrative pattern present in Gissings The Odd

Women and Allens The Type-Writer Girl: in each, a potential New Man flirts

with or marries a New Woman but is not equal to the challenge that the New

Man plot would demand and so retreats to quiet domesticity. They present striking psychological depictions of nostalgic men at the late century, torn between

desires for traditional marriage and masculinity on the one hand and progressive

models of equal, dynamic partnerships on the other. Though they are radically

different characters, Edmund Widdowson, Everard Barfoot and Mr Blank all

contemplate a life with a New Woman but are ultimately drawn to conventional

gender identities and marriages. These novels thus portray New Manhood as a

failed experiment. Yet in depicting such unsatisfying endings, Gissing and Allen

suggest a need for the emergence of the New Man, as well as for the novel to

adapt to the wider social changes that were already altering romantic relationships in late Victorian society.

Previous chapters focus on the narrative problems posed by the New Man

and how difficult it was to make space for him in either the conventional marriage plot or New Woman novel. The final chapter further asks what kind of

environments could imaginatively support such unions. Many Victorian novelists imagined their characters leaving England in order to escape restrictive

Victorian gender models. Yet the colonial New Man encountered his own set of

limitations, as the fiction of Olive Schreiner demonstrates. While various critics have emphasized the lure of self-sacrifice for the New Woman a character

trait unsettlingly connected to notions of traditional Victorian womanhood

Schreiners New Men in The Story of an African Farm and Trooper Peter Halket

are similarly defined by self-sacrifice and even self-destruction as they attempt

to adopt qualities of gentleness and healing within a context of violence and

aggression. I argue that in order to reject conventional colonial manhood, the

New Men must adopt alternative subject positions: Waldo aligns himself with

childhood, Gregory with womanhood and Peter with the position of the disenfranchised native African population. That they each, to some degree, fail in

their efforts Waldo and Peter die and Gregory reverts back to his masculine

position and enters a passionless marriage only further underscores Schreiners

incisive critique of the colonial project and patriarchal society more generally.

My conclusion briefly explores another depiction of colonial masculinity in

Victoria Crosss sensational Anna Lombard (1901), one of the few New Woman

novels narrated by a New Man. Crosss Gerald Ethridge takes the New Mans

association with empathy and healing to radical extremes: he not only waits

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 22

16/01/2015 15:07:42

Introduction

23

passively for Anna while she is married to another man, but he also nurses her

and her lover. Yet I question the political efficacy of Geralds suffering, as Anna

must kill her own child to allow for his happiness. The novel is finally ambivalent

about the social and political potential of sacrifice and the role of the New Man.

The conclusion also returns to Schreiner in a discussion of her unfinished novel

From Man to Man, written throughout the late Victorian period but published

posthumously in 1926. Though radically different from Crosss sensational novel,

Schreiners narrative too questions whether the New Man and New Womans

ethics of sacrifice might impede artistic or personal pleasure. It ends with the

meeting of the New Woman and New Man, but Schreiner did not write beyond

this initial meeting; it thus poignantly demonstrates the challenge of bringing

these experimental characters into fiction. Indeed, debates over the New Man

continued, but were by no means solved, in literary modernism and the advent of

a new century. While this book focuses on the Victorian New Man, the turbulent

emergence of New Manhood in the late nineteenth century had repercussions far

into the twentieth century, and indeed up to the present moment.

Copyright

794 New Man.indd 23

16/01/2015 15:07:42

You might also like

- An Ideal Husband ContextDocument9 pagesAn Ideal Husband ContextJosh PowellNo ratings yet

- NAPOLEON: The Legacy and the Real Extraordinary Man Behind ItFrom EverandNAPOLEON: The Legacy and the Real Extraordinary Man Behind ItNo ratings yet

- The Victorian EraDocument6 pagesThe Victorian EraFrederika MichalkováNo ratings yet

- Heathcliff As FemaleDocument1 pageHeathcliff As FemaleSteely92No ratings yet

- An Experiment in Female Government - The Habsburg Netherlands, 1507-1567Document12 pagesAn Experiment in Female Government - The Habsburg Netherlands, 1507-1567Historydavid100% (1)

- Should Auld Acquaintance: Discovering the Woman Behind Robert BurnsFrom EverandShould Auld Acquaintance: Discovering the Woman Behind Robert BurnsNo ratings yet

- Victorian Age and MoralityDocument2 pagesVictorian Age and MoralityTanishka DesaiNo ratings yet

- Theodore von Neuhoff, King of Corsica: The Man Behind the LegendFrom EverandTheodore von Neuhoff, King of Corsica: The Man Behind the LegendNo ratings yet

- Ten Years' Exile Memoirs of That Interesting Period of the Life of the Baroness De Stael-Holstein, Written by Herself, during the Years 1810, 1811, 1812, and 1813, and Now First Published from the Original Manuscript, by Her Son.From EverandTen Years' Exile Memoirs of That Interesting Period of the Life of the Baroness De Stael-Holstein, Written by Herself, during the Years 1810, 1811, 1812, and 1813, and Now First Published from the Original Manuscript, by Her Son.No ratings yet

- Derek Phillips Well-Being in Amsterdams Golden AgeDocument266 pagesDerek Phillips Well-Being in Amsterdams Golden AgeSilvia AlexNo ratings yet

- Subversion of The Cultural Revolution and Sent-Down Youth "Spirit" in Wang Xiaobo's 'The Golden Age'Document10 pagesSubversion of The Cultural Revolution and Sent-Down Youth "Spirit" in Wang Xiaobo's 'The Golden Age'mghent1No ratings yet

- Conquering Discourses of "Sexual ConquestDocument28 pagesConquering Discourses of "Sexual ConquestSantiago RobledoNo ratings yet

- Bloomsbury's Outsider: A Life of David GarnettFrom EverandBloomsbury's Outsider: A Life of David GarnettRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Joyce E. Chaplin Natural Philosophy and An Early Racial Idiom in North America Comparing English and Indian Bodies LEIDODocument25 pagesJoyce E. Chaplin Natural Philosophy and An Early Racial Idiom in North America Comparing English and Indian Bodies LEIDOVanessa MontenegroNo ratings yet

- Lili: A Portrait of the First Sex ChangeFrom EverandLili: A Portrait of the First Sex ChangeNiels HoyerRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- New Orientalism’s ‘barbarians’ and ‘outlawsDocument2 pagesNew Orientalism’s ‘barbarians’ and ‘outlawspeoplesgeography8562No ratings yet

- Doppelgangers in Dracula and The HoundDocument9 pagesDoppelgangers in Dracula and The Houndapi-280869491100% (1)

- Clifford James - Notes On Travel and TheoryDocument9 pagesClifford James - Notes On Travel and TheoryManuela Cayetana100% (1)

- Syria - The Desert and The Sown [Illustrated Edition]From EverandSyria - The Desert and The Sown [Illustrated Edition]No ratings yet

- The Greengrocer and His TV: The Culture of Communism after the 1968 Prague SpringFrom EverandThe Greengrocer and His TV: The Culture of Communism after the 1968 Prague SpringNo ratings yet

- L. DeBard and AlietteDocument2 pagesL. DeBard and AliettebiancanelaNo ratings yet

- The Red Earl: The Extraordinary Life of the 16th Earl of HuntingdonFrom EverandThe Red Earl: The Extraordinary Life of the 16th Earl of HuntingdonNo ratings yet

- The Anatomy of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. HydeDocument18 pagesThe Anatomy of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hydemerve sultan vural100% (1)

- Spain in 1830 (Vol. 1&2): Travel Narrative of an Adventurous JourneyFrom EverandSpain in 1830 (Vol. 1&2): Travel Narrative of an Adventurous JourneyNo ratings yet

- Afro-American Writing: Establishing Black IdentityDocument32 pagesAfro-American Writing: Establishing Black IdentityHEMANTH KUMAR KNo ratings yet

- Brief Autobiography of an Inconsequential Scribbler by H.P. LovecraftDocument2 pagesBrief Autobiography of an Inconsequential Scribbler by H.P. LovecraftARCHON SCARNo ratings yet

- Morien: A Metrical Romance Rendered into English Prose from the Mediæval DutchFrom EverandMorien: A Metrical Romance Rendered into English Prose from the Mediæval DutchNo ratings yet

- The Cathedral: "In all science, error precedes the truth, and it is better it should go first than last."From EverandThe Cathedral: "In all science, error precedes the truth, and it is better it should go first than last."Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Introduction To Warfare and Tracking in Africa, 1952-1990Document9 pagesIntroduction To Warfare and Tracking in Africa, 1952-1990Pickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- Index To Warfare and Tracking in Africa, 1952-1990Document8 pagesIndex To Warfare and Tracking in Africa, 1952-1990Pickering and ChattoNo ratings yet