Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Geriatric Considerations For Exercise Prescription

Uploaded by

shivnairOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Geriatric Considerations For Exercise Prescription

Uploaded by

shivnairCopyright:

Available Formats

9/10/2013

Effect of Exercise on Health

Geriatric Considerations for

Exercise Prescription

Pennsylvania State Meeting

October 26-27, 2013

Bill Staples PT, DHS, DPT, GCS, CEEAA

President, Section on Geriatrics

Posing the question does exercise

prevent or treat disease in older

persons? is analogous to asking

does medication prevent or treat

disease in older persons?

Fiatarone & Singh, Journal of Gerontology, 2002, Vol. 57A

No. 5

Objectives

Objectives

Identify the factors that affect

exercise in the elderly

Identify difficulties inherent in

describing patients by their

chronological age

Compare and contrast normal aging

Describe potential impact of exercise

on the aging process

Describe age-related changes that

affect exercise

Describe special considerations for

senior clients

Describe exercise training guidelines

and additional precautions when

managing the care of older adults

Baby Boomer Exercise

Introduction

When youre young, you challenge

your body. When youre old your

body challenges you!

Unknown

http://tinyurl.com/2u3pbz

Rehab of older adults has evolved

into an area of specialty practice

Based on evidence that aging causes

the body to respond differently to:

Injury

Disease

Exercise

9/10/2013

Chronological Age

Descriptions

Introduction

Considerable growth, now and in the

future, of the older population

Tremendous increase in individuals

reaching old age

The definition of old age is

changing due to:

Life expectancy

Medical care

Social practices

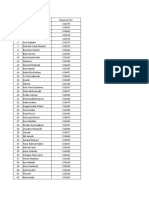

Middle age

Young old

Older

Old-old

Oldest-old

45-64 years

65-74 years

75-84 years

85-99 years

100+ years

Aging: Impact of Rehabilitation

Aging: Impact of Rehabilitation

No perfect definition of the aging

process

Aging refers to a process occurring

in living organisms

With aging comes an increased

probability of:

Elderly often contend with multiple

conditions (co-morbidities)

Physical injury and impairments are

among the most prevalent health

problems of aging

mobility independence

disability

Illness and disease

Chronic debilitating condition

Loss of function

Aging: Impact of Rehabilitation

Aging: Impact of Rehabilitation

Disability leads to increased* :

Rehab programs should be designed

to:

Mortality

Hospitalizations

SNF placement

Use of informal and formal home health

care

Cost

Restore function and mobility

Decrease pain (acute and chronic)

Decrease disability

Prolong independence

Improve quality of life

* Gill et al, 2003

9/10/2013

Aging

Is NOT homogeneous

Theories of aging differ

Genetic

Damage

Imbalance

Is aging an illness?

Death in America

50% of all deaths in U.S. due to

some sort of heart disease

70% deaths from heart disease

result from a stroke or heart attack

Much of heart disease is preventable

with healthy lifestyle including

exercise

Aging

Process differs among individuals

Variability and health status much

greater in older populations

Many adults are capable of high

degrees of activity and functional

abilities

Others display physiologic age well

beyond chronological age due to

chronic disease process

Biological Aging Changes

Normal aging changes: 0 functional

impairments or dysfunction in absence of

pathology

Maximal work capacity- gradual decline,

not noticed until critical capacity lost

Women especially susceptible due to smaller

initial muscle mass

Impacts functional status 10 years before men

Aging

Should NOT use chronological age to

determine potential for recovery or

appropriateness for rehabilitation!

Comprehensive evaluation is basis

for treatment

Clinician must recognize potential on

the individuals ability to participate

in rehab

Physiologic Reserve

Over time

Loss of adaptability

Development of impairment

Functional limitations

Disability

Loss of reserve function and

defined as frailty

Frailty Failure

Regular exercise proven to

prevent/reduce functional declines

linked to aging

9/10/2013

Exercise CapacityVicious Cycle

Usual aging- decreased

exercise capacity

Exacerbation of agerelated/disuse

declines

Increased perception

of effort/injury

Avoidance of activity

Normal vs. Pathological Aging

Pathological

Osteoarthritis

Osteoporosis

CAD

Sarcopenia

Many conditions can be prevented or

lessened with:

Normal vs. Pathological Aging

Normal aging changes occur as a

result of passage of time and are free

of pathological conditions i.e.

Presbyopia (farsightedness)

Presbycusis (hard of hearing)

Menopause

Physical Activity

However:

66% of people over 75 do nothing in

terms of physical activity*

50% of people 65-74 do nothing

42% of people 45-64 do nothing

Early and effective intervention

Appropriate patient education

Follow through

*Defined as 20 min. of exercise 3x/week

*Mokdad et al, 2001

Good Health Habits Start in

Middle Age

Consequences of Inactivity*

Hypokinetics

Middle aged adults (45-64) that began

Eating 5 servings fruit/veg per day

Exercised 2 hours per week

Kept weight down

Did not smoke

Decreased risk of heart disease by 35%

and death by 45%

Of 16,000 individuals, only 8.5% were

following these 4 guidelines at start of 6year study. By the end, another 8.4% had

joined. (still only 17%!)

King, D Amer J Med. 2007

Deconditioning

Accelerated

Loss of muscle mass & strength

Bone demineralization

Loss of neuromuscular control

Functional decline

Disuse accelerates the aging process

Heightened risk for falls

Hospitalization/SNF

*Gill et al 2004

9/10/2013

Required Tasks of Community

Dwelling Older Adults*

Cost of Sedentary Lifestyle

Estimated that U.S. could save $50

Billion per year in SNF care alone if

seniors increased activity level*

Walk a minimum of 1000 ft per errand

Often make 2-3 trips per day

Carry packages avg. 6.7 lbs while walking

Frequently encounter stairs, curbs, slopes

Engage in frequent postural transitions

Change direction, look up, reach up, move

backwards, sharp turn

Multi-tasking

So make rehab functional

*Janssen,

2004

* Shumway-Cook et al 2002

Myths about aging and

physical activity

Exercise and Health

Answer makes sense only when

exercise is described in terms of:

Modality

Dose (frequency, intensity)

Duration of exposure

Compliance with prescription

In relation to disease, syndrome,

biological aging

High intensity is not for older

persons

Resistive exercise will injure older

persons

Older persons do not have the same

functional demands as younger

persons

Older persons will accommodate

rather than challenge

Exercise??

If exercise were

a pill would

everyone take

it?

Exercise and Health

Answer makes sense only when

exercise is described in terms of:

Modality

Dose (frequency, intensity)

Duration of exposure

Compliance with prescription

In relation to disease, syndrome,

biological aging

9/10/2013

Exercise screening

Pre-screened by MD to r/o CVD, ASHD

ACSM: Stress test men >45, women >55

or known CAD, or 2 risk factors

HTN, smoking, obesity, HDL, sedentary

lifestyle, family hx of CAD, DM, known

pulmonary disease

Endurance Training

PT

Physical limitations (osteoporosis)

Goals (fitness vs. senior Olympics)

Areas of interest (gardening, walking etc.)

Role of aerobic exercise

Builds endurance

Necessary for function, ADLs

Lowers serum triglycerides

Raises HDLs

Lowers systolic and diastolic BP

Lowers blood glucose levels

Cardiovascular Exercise Slows

Biological Changes of Aging

Decrease CAD and stroke

Increases VO2 max

Lower fasting glucose and insulin levels

Lowers blood pressure

Adaptation to chronic activity can markedly

attenuate decrements in exercise capacity

due to aging

Exception: maximal heart rate

Cardiovascular Exercise Slows

Biological Changes of Aging

Improves HDL levels, lowers

triglycerides and total cholesterol

Improves body composition with 1-4%

reduction in body fat

Lowers risk for falls

Increases strength,

reduces depression

Reduces risk for diabetes

Contraindications

Recent ECG change or MI

Unstable angina

Third degree heart block

Acute CHF

Uncontrolled HTN

Uncontrolled metabolic disease (DM)

9/10/2013

Relative contraindication

Cardiomyopathy

Valvular heart disease

Complex ventricular ectopy

Cardiac rhythm originating elsewhere

than the SA node

Exercise prescription

Example

70 y.o.

Goal 60-85% PMHR for training (THR)

PMHR = 220 -70 =150 bpm

150 x 85% = 128 bpm

150 x 60% = 90 bpm

Training range 90-128 bpm

Exercise prescription

Tanaka et al 2001, hypothesized this may

underestimate HR max in older adults

Alternative 208 0.7 x age = HR max

208 0.7 x 70 (age) = ?

208 49 = 159

159 x .85 = 135

159 x .60 = 95

Target range 95-135 or slightly higher than

ACSM 2006. ACSM 2010 uses this.

Exercise prescription

ACSM (2006)

Intensity: Max HR assessed directly

thru age predicted (PMHR)

PMHR = 220-age

Training range between 60-85% max

HR

May not be accurate in the elderly

Karvonen Method

Factors in resting heart rate (HRrest) to

calculate target heart rate (THR), using a range

of 5085% intensity:

THR = ((HRmax HRrest) % intensity) + HRrest

Example for someone age 70 with a HRmax of

150 and a HRrest of 70:

50% Intensity:((150 70) 0.50) + 70 =110

bpm

85% Intensity: ((150 70) 0.85) + 70 = 138

bpm

Monitoring Endurance

Heart rate can give you a good

measure BUT because older adults

may have multiple disease processes

ongoing, in addition to medications,

that it is best to use the RPE!

ACSM 2010 has different HR

recommendations for different

diseases

9/10/2013

Anaerobic & Aerobic Exercise:

Body Composition

Reduces adipose tissue, visceral fat

Prevention & Rx of insulin resistance

syndrome, CVD, gall bladder

dysfunction, Type 2 diabetes, types of

cancer, hypertension, stoke, OA

Duration

Ranges 20-60 min (most 20-30 min)

Does not include warm up or cool

down

Typically inversely related to

intensity

May increase secondary to training

effect

Examples of moderate

intensity exercise

Fishing stand, cast

and walk along bank

Canoeing leisurely (24 mph)

Mowing the lawn with

walk behind power

mower

Home repair, painting

Frequency?

Range from 3-6 days /week to

2x/week

Dependant on intensity and duration

Dependant on functional capacity

Intensity

Cardiovascular

Moderate activity, total 30 min. per

day (sessions as short as 10 min.),

minimum 3 days/week

Requires 3-6 METS or 4-7 kcals/min

Examples of moderate

intensity exercise (cont.)

Walking briskly (3-4 mph)

Cycling leisurely (<10

mph)

Swimming with mod.

Effort

Doubles tennis

Golf, using a pull-cart

9/10/2013

Strengthening of the Older

Adult

Principles of Intervention

Overload

Task specificity

Adapt vs. challenge

Benefits

Prevent/slow strength decline

associated with aging

Decrease resting BP

Systolic 5mmHg,

Diastolic 3mmHg

Improved blood lipid profile

Weight loss

Improved wound healing

Increased bone density

Strengthening exercise

Why

Strengthening may be the most critical

parameter of exercise and may be

safer for people with

COPD (Simpson, 1992)

CHF (Pu et al, 2001; Levinger, 2005;)

Arthritis (Fransen et al 2002)

Than aerobic exercise. Especially in

the elderly.

Because aerobic exercise is typically

a whole body (running, swimming) or

minimally a half-body (cycling) which

requires a great deal of effort and

energy for an inactive person.

Strengthening is performed one

muscle group at a time for short

duration.

Loss of strength leads to:

Functional needs

Functional limitations

Gait speed LE power relationship

Bassey et al Clinical Science 1992

Sit to stand hip and leg strength

Gross et al Gait and Posture 1998

Falls risk of falls

Whipple et al JAGS 1987

Percentage strength requirements (leg

extension) in elderly

- 80% sit to stand

- 78% ascending stairs

- 88% descending stairs

- Frail 97% for sit to stand

Hortobagyi et al, J Gerentol Med Sci 2003

ADLs indices

Hyatt et al Age and Aging 1990

9/10/2013

Improved Psychological

Well-being

Participation in physical activity:

More positive psychological attributes

Decreased incidence and prevalence of

depression

Effects most noticeable in elderly with

co-morbidities

Muscle Mass and Aging

Overloading muscle can largely avert

losses of muscle mass and strength

Older men who lifted weight for 12-17

years > men 40-50 years younger

(strength)

PRE of 3-6 months can increase muscle

strength 40-150%, depending on subject

characteristics

Increase LBM (lean body mass) and

muscle fiber by 10-30%

Overload

Overload

Must be individualized and applies to:

Muscle strength is best developed by

using weights at levels that evoke

nearly maximal muscle tension with

relatively few repetitions

Any overload will result in strength

development, but higher intensity

effort at or near maximal effort will

produce a significantly greater effect

Intensity

Duration

Frequency

Speed

Intensity

Older adults gain strength similarly to the

young

2-3x in strength in 3-4 months, 11.4% in

muscle area (Frontera 1990, Fiatarone 1994)

Strength with 60-100% 1RM training

(McDonagh & Davis 1984)

Overwhelming evidence that low intensity

produces only modest gains in strength

With 80% 1RM significant gains even in the

very old (Fiatarone 1990, Evans 1999)

High intensity is safe even in the frail elderly

Relationship between strength

& Function

Leg power is powerful predictor of

functional decline (Mazzeo et al 1990)

Walking speed and LE strength

strong predictor for SNF placement

(Guralink et al, 1994)

Loss of LE strength strongest single

predictor for institutionalization

(Judge et al 1996)

10

9/10/2013

Functional strength vs.

Absolute strength

Power & Function

Often a deficit between the two

Functional strength is

usable/integrated strength and

incorporates velocity (force x velocity

= power)

Increasing functional strength

increases absolute strength

Training functionally meets the criteria

of specificity

Power was a better predictor of

physical function than isometric or

isotonic strength (Bean et al 2003)

Leg power and self-report of physical

activity had strongest correlation

with function (Foldvari 2000)

Frequency

Frequency/Duration/Intensity

ASCM: 2-3x/week

48 hour rest

Task Specificity

Low resistance, high reps lead to

endurance improvement (increase in

mitochondria), but little change in strength

(Moffroid & Whipple)

Important for function

2x/week gives 80-90% all strength

gains in untrained individuals

(compared to up to 6x/week)

1 set as effective as 2 or 3 (with proper

intensity)

75-85% of 1 repetition max

8-12 reps (set must go to muscular

failure)

1 set saves time/better compliance

Specificity

The more frail the more important

May be an alternative to intense

resistance (Page, 2003)

Multiplanar

Balance dominated

Asymmetrical

Velocity specific

Progressive

Eccentric (stairs, transfers)

Open or closed kinetic chain

11

9/10/2013

Function

Specificity includes functional task

training

Patient-centered (driven)

Meaningful

Progression

Try to keep load at 80% 1RM, 8-12

reps

Typically reps then load

McCartney 1996 suggests q 2week

eval

Early strength gains 10-15%/week

first 8 weeks may be due more to

neural factors

(Evans 1999, Bemben & Murphy 2001,

Phillips 2000)

Flexibility

ACSM recommends flexibility

training in older adults esp. shoulder,

neck, upper & lower trunk, and hip

regions.

Freland 2002 suggests hold for 60

sec in older adults

Injury

NO evidence to support higher rate

of injury in elders with intensity

(Rooks 1997, DiFabio 2001, Barnard 1999,

Coleman 1996)

No adverse cardiac events with high

resistance or Valsalva maneuver

(Gordon 1995, McCartney 1996, Barnard

1999, Vermill 1999, Kaelin 1999)

How many exercises

Henry et al, 1998 looked at elder

compliance

Study looked at 2, 5, 8 exercises

2 ex group had best compliance

ACSM recommendations

5-10 minute warm-up includes

stretching

30 min/day 3x/week

Walking bicycling, swimming, running

Resistance training: use proper body

mechanics (quality not quantity)

Include large muscle groups

Cool-down with stretching

12

9/10/2013

Summary of strengthening for

the elderly

< 5 exercises

1-3x/week

1 set, 80% 1rep max

8-12 reps

Considerations for power, eccentric

loading, closed/open chain, and

functional/task training

Summary

Several major research studies have considered

the numerous factors that seem to predict the

need for eventual institutionalization, and LACK of

leg strength was found to be the single most

important predictor. Not blood pressure, or heart

disease, or diabetes, or arthritis but rather leg

strength. The lesson is clear. If you want to avoid

the nursing home, youd better take good care of

your legs.

Walter M Bortz II MD, Professor Stanford University

Fun facts for home ex

Chronic Diseases Amenable to

Exercise

Soup can = lb

Can of tomatoes = 1lb

Jar peanut butter = 2 lbs

Bag of sugar = 5 lbs

Gallon of milk = 8 lbs

Lack of exercise contributes to chronic

disease:

Chronic Diseases Amenable to

Exercise

Prevention of Chronic Disease and

Increased Longevity

Exception: Progressive Diseases of

the CNS

However:

Lack of physical activity exacerbates

symptoms and hastens loss of

functional mobility

CVD

Stroke

Type 2 Diabetes

Obesity

Hypertension

OA

Depression

Osteoporosis

Evidence that both healthy and

chronically ill are candidates for

preventive exercise

Preventive ex appropriate for:

Community-dwelling

Institutionalized

13

9/10/2013

Adverse Effects of Exercise:

Adverse Effects of Exercise:

Community, Institutional Settings

Experienced Senior Athletes

Rare

Associated with

increase in activity

that is too sudden

and not gradual

Hamstrings, feetmost common

areas

Improper footwear

Walking programs

Jogging programs

Weight lifting (very

rare)

Adapt vs. Challenge

First responsibility is to make pt.

safe

After that need to increase challenge

Remember what is needed for

community living

Challenge with

Changing surfaces, uneven

Obstacles

Impose activities with gait

Increase speed

Complex gait activities

Heel/toe walking

Side-stepping, cross-overs, braiding

Tandem, backwards

Strains most

common

Hamstrings, calf,

adductors,

quads

Rotator cuff

muscles and

tendons

Sprains

Ankle

Knee

Fractures

Rare,

associated

with cycling

Strength changes

Early effects of ex:

Deconditioned-Neural Adaptation

(therapy)

Long-term effects of ex:

Stronger-Hypertrophy (fitness)

Age-related Musculoskeletal

Changes that affect exercise

Muscle mass and strength

Decreases 30% between ages 60-90

Muscle fiber

Type II decreases 50% between 60-90,

decreases 1% per year after age 30 with no

exercise

Motor unit

Decrease recruitment

Speed of movement

Decreases

14

9/10/2013

Age Related Changes

Bone

Tensile strength decreases, by age 70 a

decrease of 10-15% peak bone mass

Joint flexibility

Reduced by 25-30% over the age 70

Tendons

Cells

Rate of cellular division decreases

and becomes irregular

The functional effectiveness of

enzymes within the cells does not

diminish with age

Become less elastic and easier to tear

Cartilage

Collagen fibers increase cross-linkage

increasing the density of tissues reducing

movement

ELASTIN FIBERS

GLYCOPROTEIN

Dehydrate and increase cross

linkage with age

With the decreased elasticity, the

fibers become rigid and frayed

Elastin fibers are ultimately replaced

with collagen fibers which decreases

mobility leading to shortening and

distortion of the tissue

Production and release of

glycoprotein results in dehydration

of tissues

Results in water content decrease in

muscles and tendons causing

stiffness and rupture at less stress

than in younger ages

HYALURONIC ACID

Regulates the viscosity of tissues to

decrease friction between tissue

layers with movement

As this secretion decreases, greater

friction occurs resulting in the wear

and tear between tissues

MUSCLE MASS Age Changes-

Sarcopenia

Between age 20 and 80:

20-30% muscle mass loss occurs

Greatest loss is between 50 -80 years of age

Muscle strength decreases 15% per decade

between 50-70

Muscle strength decreases 30% between 70-80

Muscle mass is replaced by fat and collagen

deposits resulting in no change in overall girth

or volume measurements

15

9/10/2013

Muscle Fibers

Muscle Mass changes

As muscle fibers are lost, remaining

have to work harder to produce the

same force

Energy demands are raised resulting

in fatigue and decreased endurance

Muscle fiber hypertrophy can occur

in remaining fibers to increase

strength and function in even the

very old

Begins at age ~40: muscle mass will

decrease .5-1%/year over youth size

By age 75: there is ~30-40% decrease

in muscle mass

As one ages there is an increase in

fat and a decrease in Muscle mass

Muscle vs. Fat

CARTILAGE

As muscle fibers are lost, fat is

deposited

Fat is not as metabolically active as

muscle

Older people gain weight easier than

young

The collagen in cartilage holds less

water with age

The rate of collagen and elastin

synthesis decreases resulting in

dehydration and stiffness

fraying of cartilage.

CARTILAGE

With loss of movement, nutrition to

cartilage is reduces resulting in

thinning of cartilage and less ability

to dissipate forces across joints:

Results in damage and friction

leading to tearing and fraying of

cartilage.

Age Changes

COLLAGEN CHANGES

Main supportive protein in skin,

tendons, bone, cartilage, and

connective tissue

As we age, collagen becomes:

Irregular in shape

Less uniformed, less parallel in nature

Less mobile and slower to respond

cross linkages

nutrient movement thru tissues

16

9/10/2013

Review

MUSCLE STRENGTH DECREASE

100

Normal change

90

80

70

60

50

40

Inactive

30

Slow Twitch Type I muscles are

highly oxygenated and used in ADLs

Fast Twitch Type II muscles are used

in more intense activity/resistance

training

20

10

0

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Motor Unit Level:

Decrease number of motor neurons

Decrease number of muscle fibers

Type II decreases more rapidly than Type I

By age 75, there is more Type I fibers

than Type II, EVEN in Senior athletes

Typical Changes with Aging

Reduced flexibility in the lower

extremity joints

Decreased strength of the ankles,

knees and hips

Less control of momentum

Decreased coordination and

Typical Changes with Aging

Decreased reflexes and increased

reaction time

Vision and sensory changes

Gait: slower speed, shorter step,

narrow stride width

Balance

Static:

Decreased as a result of decreased

ankle strength

Dynamic:

Decreased hip, ankle and stepping

strategies

Increase use of sway

Sway accounts for dynamic balance

in 80 y.o 50 % more than in 40 y.o.

17

9/10/2013

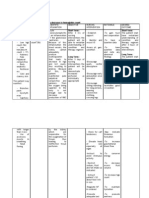

Changes

All the changes combine to cause

impairments, functional limitations

and disability

Disease/Impairment

Functional

limits/disability

1.Decrease muscle strength

Deconditioning/falls

2.Decrease aerobic capacity

Deconditioning/falls

3.Vasomotor instability

Baroreceptor insensitivity

Syncope/dizziness

4.Decrease total body H2O

Dehydration

5. Decreased bone density

Fracture risk

6. Fragile skin

Wounds

7. Altered thirst, taste, smell

Dehydration/malnutrition

Evidence

Do strength/ROM relate to function?

YES!!!!!

Musculoskeletal impairments (LE

strength and ROM), have a strong

relationship to function, especially in

older adults.

Beissner KL, et al., Muscle Force and Range of

Motions as Predictors of Function in Older Adults.

Phys Ther 2000. Jun;80(6):556-63.

Functional

Changes

Posture:

Tight knee flexors

Tight hip flexors

Increased lumbar

lordosis

Tight Pectoral

muscles

Evidence supports the idea that

exercise can overcome some of

these impairments and limitations!

Evidence

High intensity training.not just for

the young!

Average of 174% strength gains after

8 weeks of high intensity training.

This correlated improved mobility to

residents up to 96 years old!

High-Intensity Training in Nonagenarians. Effects on

Skeletal Muscle. Fiatarone M, et al., JAMA June

1990. 263(22):3029-34.

18

9/10/2013

Dynamic Exercise

Light work:

Works only Type I muscle fibers

Good for cardiac patients to start

Heavy work:

Works Type II muscle fibers

First 2 weeks it is the neural component

that is stimulated

Work at 80% of 1 rep max

Exercise and pathology

Skeletal Changes affecting

Exercise

The breakdown and eventual loss of

the cartilage of one or more joints

Osteoarthritis occurs when the

cartilage begins to fray, wear and

decay. In some cases, all the

cartilage wears away leaving the

bones of the joint to rub against each

other.

1 in 4 will develop symptomatic hip

OA by age 85; women> men

Falls

Depression

Cardiovascular

& pulmonary

CVA

Parkinsons

OA: S&S

OA

Osteoarthritis

TKA, THP

Hip fracture

Osteoporosis

Frailty

Stiffness

Joint pain

Crepitis

Inability to perform tasks

These can range from mild to severe.

Pain with weight bearing

Palpable warmth

Bony enlargement

Osteoarthritis

Muscle weakness contributes to

symptoms (esp quads) 2o joint reaction

forces

Adults > 65 with chronic knee pain

experience significant declines in

balance and LE strength over 30 month

period (Messier 2002)

19

9/10/2013

OA

Osteoarthritis

OA afflicts 20 million

Obesity risk by almost 2x

THR, TKR on the rise

2004: 431,485 TKR; 225,900 THR

2015: 1.4M TKR; 600,000 THR

Medicare wont be able to pay for all

these!

New guidelines! Require exercise

Osteoarthritis

Strongest quads show less knee

cartilage loss (Amin 2006)

Patellar/shoulder taping: reduces pain

and allows increase in function

(Quilty 2003, Hinman 2003)

Proper alignment is vital to PRE

Walking, jogging, recreational ex.

Does not risk of OA (Felson 2007)

Obesity increases risk, but no extra

increase with exercise

Differentiating age-related changes

from osteoarthritic changes

Age Related Changes

OA

Cartilage

Decreased

hydration

Increased

hydration/swelli

ng

Subchondral

Bone

Thinning

Thickening

Synovium

No Change

Swelling

proprioception contributes to

development of OA

Programs that incorporate

proprioceptive training with

strengthening decrease symptoms

better

OA

PACE: People with Arthritis Can Exercise

Program

8 weeks: decreased pain & fatigue, increase

in function (chair stand, 10# lift), increased

self-efficacy.

program that focuses on stretching,

flexibility, balance, low impact aerobics, and

strength training exercises

CDC funded

http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/funded_science/projects/

pace-people-with-arthritis-can-exercise.htm

OA

The majority of persons over the age

of 65 and 80% over the age of 75

have radiographic evidence of OA in

at least one joint.

Can affect any joint; most commonly

seen in the hands and weight bearing

joints primarily the hips and knees.

20

9/10/2013

OA

Exercise and OA

The proper exercise program for the

elderly individual needs to consider

any underlying pathology and

modified for successful results

Strengthening ex pain, function

Exercise in water has been shown to

reduce pain.

Proper footwear pain

Musculoskeletal aging

Changes in cell and

tissue function

Sarcopenia

Joint laxity

Musculoskeletal underuse/misuse

Lack of exercise

Abnormal joint loading

TJR

Joint replacement is a last step when:

Musculoskeletal dysfunction

Risk Factors

Obesity

Joint instability

Joint injury

Genetics

Anatomy

The risk of immobility is greater than

the risk of exercise and can lead to

further aging changes.

Stronger muscles generally reduce

stress on the joint surfaces by

correcting abnormal biomechanics

Exercise can initially increase the

symptoms but not cause an increase

in the damage to the joints

OSTEOARTHRITIS

Total Knee Arthroplasty

Quad strength 62% from pre-op. at

1 month post-op

4%/day with immobilization

With high intensity ex can return to

pre-op in 2 months (Mizner 2005)

Walking and stair climbing is difficult

Pain at rest and at night is not controlled

6-week presurgical ex program can

improve post-op status (TKA & THR);

and reduce odds of requiring inpatient

rehab stay

Rooks et al. Arthrits Rheum.

2006.15;55(5):700-8.

Evidence

Strengthen quads, including leg

press if FWB

If significant quad insufficiency

present, add e-stim for 1st 6 weeks

21

9/10/2013

Gender Bias

Study from Canadian Med Assoc J.

March 2008

Orthopedic surgeons were 2x more

likely (33% to 67%) to recommend TKR

to men over women with same

symptoms

Hip Fracture

Total Hip Arthroplasty

At one year 10-18% strength deficit

around hip (Trudelle-Jackson 2004)

Hip abductor strength directly related

to return to home, risk for falls,

function, gait status

Hip Fracture

75% fail to return to previous level (Weinrich

2004)

At 2 months post: (Magaziner 2000)

98% had some dependency walking 10 feet

At 6 months post: (Magaziner 2003)

Only 8% climbed a flight of stairs

15% could walk across a room independently

6% could walk half a mile

At 24 months:

50% still had difficulty walking 10 feet independently

Hip Fracture

Post: 53.3% fell, 62,5% of these fell >2x, 18%

sustained injuries requiring re-hospitalization

Predictors for fall 6 months post (ShumwayCook 2005)

Previous use of assistive device 3.15x

Hx one fall prior to fx 8.77x

At 2 years post (Norton 2000)

4x more likely to be homebound

3x more likely dependent for ADLs

The more PT in hospital the better mobility 2

months later. (Penrod 2004)

Hip Fracture

At 8-12 weeks moderate stability

from bone callus is achieved

Time to begin aggressive strengthening

and wean from assistive device

(Weinrich 2004)

High intensity exercise for 3mo & 6

mo have been shown to gait speed,

distance, balance and function

(Binder 2004, Mangione 2005)

22

9/10/2013

Issues for acute hip injury

SLR

Greater stress on hip joint with SLR than

normal unsupported gait (Strickland

1992)

SLR = 3x body weight

Maximal isometric abduction greater

peak pressures than SLR or unsupported

gait. (Krebs 1991)

Issues for acute hip injury

Forces of hip abductors during gait =

2.5x body weight

Forces on hip joint during stair

climbing = 7x body weight

Forces on hip during

running/jumping = 10x body weight

Davy et al 1988

Spinal Stenosis

Spinal Stenosis

Degeneration of the intervertebral disc

which results in collapsing of the disc.

The collapsed disc and subsequent facet

arthrosis narrows the neuroforamen and

compresses the nerve root.

The ligamentous laxity causes vertebral

subluxation and osteophyte formation

resulting in spinal stenosis

The neuroforamen is narrower with

lumbar extension than with flexion.

The patient with spinal stenosis will

prefer to sit and flex versus standing

with extension.

The obstruction can also impair

cerebrospinal fluid circulation and

produce the neuroischemia.

Spinal Stenosis

S&S

Spinal stenosis primarily reflects disc

and facet degeneration but as time

progresses,

Spondylolisthesis can occur.

Costs $1 billion annually

Slow progression of disease

Numbness, weakness, cramping,

pain in Les, feet, buttocks

Compresses spinal nerves

Similar to disc

Stiffness in LEs

LBP

Decreased LE sensation

Loss of bladder and bowel function

in severe cases

23

9/10/2013

S&S

Often have absent lordosis

Stooped posture when standing or

walking

Prefer to use walker, grocery cart,

w/c to enable forward lean

This can increase risk for falls

Intervention

Aerobic conditioning utilizing a

stationary bike/treadmill

Aquatic exercise to reduce the stress

on the spinal joints.

Manual stretching, muscle

strengthening

Flexion decreases symptoms,

extension aggravates

The goal of should be 30 minutes of

exercise 3x/week.

Intervention

Pharmacological Interventions:

NSAIDS ; Lodine; ibuprofen

Analgesics:Hydrocodone,

acetaminophen

Education on proper body

mechanics

Restriction of aggravating activities

Spinal stabilization

Later Interventions

Epidural Steroid Injections

short term relief only

success rates are only 85%

The best results seem to occur with patients

who have had decompression surgery at one

or two levels and no spondylolisthesis

Surgical Decompression

laminectomy

X-STOP IPD procedure: less invasive, metal

implant that limits spinal extension

Complications

Osteoporosis

Patients with osteoporosis and

spinal stenosis will often develop a

compression fracture proximal to the

fusion.

Pelvic fractures are often seen after a

lumbosacrel fusion due to the

increased stress on the pubic rami

during rotation

A disease characterized by low bone

mass and structural deterioration of

bone tissue, leading to bone fragility

and increased susceptibility to

fracture.

24

9/10/2013

Bone Basics

Bone Basics

Bone grows in length up to age 25

Osteoblasts can continue to lay down

new bone until age 30

10-15% of skeleton is demineralized and

can be renewed each year

Osteoclasts take calcium out of blood to

put in blood stream

Osteoclasts take out in one month what

osteoblasts takes 3 months to replenish

Bone mass accounts for 75-85% of

bone strength

25 year olds absorb 75 % of available

calcium, 60 year olds 30-40 %

Physical inactivity can lose 1 % of

bone mass/week

Trabecular bone loss begins age 30-40

Cortical bone loss begins age 40-50

Bone Remodeling Cycle

Type I (post menopausal)

Osteoclast activity: bone

breakdown

Osteoblast activity: bone

formation

Normal balance =

turnover of 10% cortical

and 30-40% trabecular

bone remodeled per year

Trabecular Bone

Trabecular bone loss is 3x the

normal loss

Bone loss is greater in first 5 yrs

after menopause

10-15 yrs after menopause the loss

rate decreases

Most associated with vertebrate and

wrist fractures

Type II (age related)

Loss beginning at age 30

At age 40:

less bone is formed than is reabsorbed

loss is .3-.5 %/yr.

Decrease ability to absorb calcium

Associated with hip fracture

25

9/10/2013

Height

Disc height maintains or slight

increases with age

Does decrease during day, but

replenishes at night

Osteoporosis - Diagnosis

Through Bone Scan

Visualization

Arm measurement

Loss of height is a decrease in

vertebral height (body of

vertebrate)as a result of decrease

bone mass not disc

Men DO get osteoporosis

A major public health threat:

1-2 million in U.S.

8-13 Million have osteopenia

500,00 hospital admissions (fx)

Men sustain 25-30% of hip fractures

Associated with low testosterone

Healthy People 2010 identifies this as the

second focus area to address to improve

the quality of life in the USA

44 million Americans have the disease or

have low bone mass (osteopenia)

Occurs in both men and women

Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:47-54

Mortality rate is 2x

Article on Blackboard

A major public health threat:

Affects the physical independence in

daily activities

Responsible for 1.5 million fractures

annually

Direct expenditures as a result of the

fractures at $13.8 billion/year and rising

4x more likely in women. 1 in 12 men (low

estrogen)

Affects all age groups and ethnic groups

Pharmacological Interventions: To

slow bone loss

Fosamax/Boniva: in both men and

women

Actonel: in women and men

Raloxifene: in women, selective

estrogen receptor modulator

Calcitonin: in postmenopausal

women greater than 5 years and

relatively healthy

26

9/10/2013

Some problems

Use of bisphosphates (Actonel,

Fosamax) is linked to bone necrosis,

esp. jaw.

Journal of Rheumatology .Feb 2008

Fosamax may also cause chronically

irregular heartbeat (atrial firillation)

by 86%

Fractures

Fractures are more highly related to

decrease bone mass than any other

age related factor

Most common fractures (in order):

vertebral, hip, wrist

Arch Int Med. Feb 2008.

Fractures

Femoral neck

ORIF: poorer outcomes than

hemiarthroplasty

Hip fractures: DM = higher risk

despite higher BMD (bone mineral

density) (higher body weight?)

Visual impairment?, sensation?,

CVD?

Diabetes Care 2007;30:835-41.

Surgeries

THR, ORIF

Vertebroplasty: for comp. fxs

Lab

Flexicurve video

Injection of cement

+/- risk for adjacent fx

27

9/10/2013

Research shows:

Exercise can gain bone mass

dynamic bone loading exercises of

walking, jogging and stair climbing

Strength training stimulates bone at the

muscular skeletal junctions

Rest periods to prevent desensitization

may double anabolic responses to

mechanical loading

Evidence

Significant relationships were recorded

between dynamic leg strength and BMD of

the femoral neck and lumbar spine

Effects of one-year of resistance training on the

relation between muscular strength and bone

density in elderly women. Rhodes. Br J Spts Med.

2000

Contraindicated exercises include

vertebral flexion exercises

Osteoporosis

Resistive exercises appear to

increase bone mass density

Increase back muscle extensors

Women with weak back extensors are

2.7% more likely to suffer a

compression fracture

Exercise

May work best to build bone during

bone growth, with some lasting

benefits, but may erode away when

exercise stops

In adulthood, small increments

No evidence that ex fractures

Issues for osteoporosis

Avoid trunk flexion, especially with

resistance

Careful with dynamic body weight ex.

28

9/10/2013

PT Intervention

BEST exercise program

AGING JOINTS

Designed at Johns Hopkins

http://www.citracal.com/best/

Exercise videos

Foot/Ankle

Knee

80% of people 65 and older have foot

dysfunction

Loss of flexibility of the ligamentous

structure between the 26 bones of

the foot

Decrease range of motion and shape,

therefore the reason to measure your

foot when buying new shoes

Decreased ankle strength affects

balance and mobility

Degenerative changes in weight

bearing joints increases and the knee

changes are 2x as common as the

ankle or hip

Women have a 50% greater strength

loss and greater magnitude of varusvalgus deformity than men possibly

due to the decrease in estrogen after

menopause

Hip

Hip

The weight bearing surface of the hip

is covered with cartilage which crack

and shred over time resulting in

fissures

Degenerative joint disease and hip

bursitis are the common complaints

The synovial membrane thickens and

are less mobile unable to protect the

joint

Common findings include: hip

flexion contractures, weakness,

iliotibial band contractures, and

disuse atrophy from habitual sitting

60% of gait cycle is in stance and

35% in one legged stance, therefore

hip instability and weakness will

affect gait

29

9/10/2013

Spine

Cervical Spine

The spine tries to stabilize itself with

bone remodeling resulting in bone

spurs or widening of the vertebral

body

Postural changes as result of

tightening of the pectoral muscles

and habitual sitting

The disc changes by a decrease in

size and number of the collagen

resulting in less elasticity, and

posterior migration which begins the

forward head posture

Long anterior neck muscles shorten

and the suboccipital muscles tight to

keep head in vertical alignment

Cervical Spine

Shoulder

Decrease cervical range of motion

can begin as early as age 30

Bifocals/trifocals, pillows for

sleeping, computer usage can all

contribute to neck changes

Shoulder pain is more frequent in

women than men

Deltoid muscles are the most

overworked and rotator cuff the least

worked of all shoulder muscles

Shoulder

Hand

Decrease supraspinatus strength

results in superior migration of the

humerus and ultimately impingement

in the subacromial region

Increased thoracic kyphosis as a

result of back changes increases

shoulder problems.

Multitude of small joints, cartilage,

and muscles predisposes the hand

to aging effects

Routine daily stresses on the joints

of the hands add up over time

Joint protection techniques, utilizing

larger joints, energy conservation

and pacing all help to reduce hand

dysfunctions

30

9/10/2013

Frailty

Definition: 3 or more

Unintentional wt loss of > 10 lbs in last year

Self-reported exhaustion

Weakness (lowest 20% grip strength for

age

Slow walking speed (lowest 20%)

Low physical activity

1-2 of these factors signal intermediate

frailty with risk to become frail in 3-4

years (Fried 2001)

Frailty and Resistance

Exercise

Resistive ex in hospital improved

strength, sit to stand. Gait speed and

4 of 6 non-ambulatory pts. Became

ambulatory (Sullivan 2001)

Falls

Decreased incidence of falls for

those placed on exercise programs

Resistive ex.

Balance ex.

Tai Chi

Xi Gong

Yoga

Frailty and Resistance

Exercise

Appears to be a major weapon to

combat frailty

80% 1rm:

174% in 90+ older adults 3x/week for 8

weeks; 3 sets of 8 (1st week 50%)

227% gain knee flexor, 107% gain knee

extensors

Evans 1999

Falls

Resistive exercise increases balance,

gait velocity, climbing power and sit

to stand

Depression

Mod high intensity exercise improves

self scores

Depression doesnt limit gains from

physical activity

Singh 2002

More about this in lecture 5

31

9/10/2013

Cardiovascular Disease

Resistance exercise may be more

tolerable that aerobic exercise if

ischemic threshold is low due to

heart rate response to training

COPD

Exercise improves muscle strength

and endurance, dyspnea, QOL

CHF

No longer contraindicated, but must

monitor vitals signs

Diabetes

Resistance exercise is as, if not more

effective than aerobic ex. in

improving glucose intolerance and

risk reduction

COPD

Fewer repetitions are tolerated

better, single set, 2-3x/week.

Progress from 50% to 80% 1RM

Time exercise sessions after

bronchodilator med peak

Use oxygen as needed

Monitor vitals, RPE (Borg)

CVA

Overload principle (Weiss 2001)

One-year s/p

12 weeks, 2x/week, 70% 1RM

68% increase in strength, 12% balance,

sit to stand improved

Treadmill supported gait

32

9/10/2013

Parkinsons

Parkinsons

Rigidity leads to flexor

muscle and soft tissue

shortening, extensor

muscle and soft tissue

lengthening

Exaggerated exercises

Forced exercise

Boxing training

http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/suppl/2

010/12/29/91.1.132.DC1/Combs.mov

Relaxation exercises

Strengthening increases

stride length, LE strength,

gait velocity, head angle

8 weeks, 60% 1RM (Goede

2001)

Causes of Inactivity in

Seniors

Causes of Inactivity

Lack of motivation or apprehension

Lack of resources, or knowledge of

them

Social/cultural issues

Environmental barriers - e.g.,

equipment, room to exercise, place to

walk, transportation

Inability to assume positions/postures

Exercise and Older Adults

Inactivity Increases with Age

Percent

50

70-79

80+

40

Benefits of ex., proper methods for performing

ex.

Today, about 28% to 34% of adults 65

to 74 and 35% of adults 75 years and

older are INACTIVE.

By 2030, demographers expect the

number of older people to double,

from 35 million to 70 million.

70-79

60-69

10

0

Muscle soreness, shortness of breath

Lack of knowledge

60-69

30

20

Falling, getting injured, not doing it right

Acute illness

Co-existing diseases/disabilities

(incontinence)

Unpleasant sensations associated with

exercise

Inactivity

80+

60

Fear

Men

Women

33

9/10/2013

Factors that Improve Exercise

Adherence in Seniors

Motivation is the best discriminator for

older adults who enroll and adhere to

and/or drop out

Strategies to improve motivation:

Effective exercise leader

Continuity

Type of program variety, cross-training

Have FUN!!

Self-efficacy

Expected outcomes

Exercise Leader

KEY TO SUCCESS IS MOTIVATION!!!

Encourage participation, assess,

instruct

Demonstrate caring

Aware of participants differences

Well-organized

Able to establish rapport with group

Begin slow and advance slowly (to

avoid pain, SOB)

Individualized Programs

Individualized, even within groups

Some seniors prefer to exercise

alone

Find out who these individuals are

One-on-one interview

Customized program

Consulting/counseling

Assess: type/freq/intensity/duration

Advise: importance of ex

Agree: shared decision making

Assist: printed

materials/calendar/resources

Arrange: Follow-up/referral to specialist

Type of Exercise or Activity Programs

Group Programs

Strength Training

Walking

Yoga

Tai Chi

Feldenkrais

http://rehabyoga.com

Dancing

Qi gong

Chair w/c ex.

Floor ex.

Mechanical

Bicycles

Treadmills

Ellipticals

Stair steppers

Exercise and Aging

Regular exercise has been shown to

decrease morbidity in older adults

Despite this fact, less than 25% of the

older population exercises at

recommended level!

Only 37% of PT pts cont. HEP 6months

after D/C*

Why?

*Forkan Phys Ther 2006;86:401-410

34

9/10/2013

Barriers

Disability specialized

program/exercises from PT

Fear of injury/Falling initial

supervision 1 on 1

Habit need to incorporate into daily

routine

Lack of education

Income level

Barriers (cont.)

Environmental weather

Cognitive decline keep it simple

Lack of nutrition meals on wheels,

education

Ability to Manage

Perceived Barriers!

Self-Efficacy

Factors that affect self-efficacy:

Age

Gender

Previous experience

Take Care of the

Barriers to Exercise

Deal with Barriers

Fear!

Location

Transportation

Personally

appealing

Client-centered

goals

Opportunities for

success

Address

discomforts

Safety, falling

Address embarrassments

Encourage questions

Acknowledge each success

Buddy or partner system

35

9/10/2013

Deal with Barriers

Environment

Safe, pleasant, health-enhancing

Convenient

Societal/cultural issues

Customize Program

Outcome Expectations

Stronger outcome expectations

associated with starting exercise and

maintaining it

Clear and accurate

Realistic?

Favorite activities, specific goals

If co-existing disease/disability

Special for Seniors

Rely heavily on

instructor

Enjoy interaction

with a group, may

be more effective

(own age)

Contributes to

self-esteem

Physical Activity:

A Key to Wellness and

Successful Aging

Wellness

A lifelong interactive process of

becoming aware of and practicing

healthy choices to create a more

successful and balanced lifestyle.

How do I teach my seniors?

How do I stress the importance of

exercise?

How does a PT tell their

patients about the

importance of exercise?

36

9/10/2013

Physical Activity Improves

Intellectual Function by:

Helping maintain cognitive function

(e.g. memory and concentration)

Decreasing stress and anxiety

Improving mood

Reducing depression

How Do I Get Started?

Check with your doctor

Visit a physical therapist

Start slowly

Integrate different physical activity

components into your life

Choose activities you enjoy

Get a buddy

How Do I Choose an Activity?

Consider including multiple

components

Enjoyable

Accessible

Convenient

Variety

Physical Activity Improves

Social Function by:

Increasing independence

Creating a stimulating,

and often supportive,

environment

Improving family time

Increasing social

networks and

involvement

Getting Started

The National Institute on Aging has

published the 2009 version of

Exercise and Physical Activity: Your

Everyday Guide from the National

Institute on Aging. Best of all it is

free!

http://www.nia.nih.gov/HealthInforma

tion/Publications/ExerciseGuide/

Meeting Their Needs

Considerations for

group programs:

Class size

Instructor experience

Amount of assistance

they need

Intensity and variety of

program

37

9/10/2013

Physical Activity May Include:

Walking

Swimming or

participating in a

water exercise

class

Playing a sport you

enjoy

What If I Have Physical

Limitations?

Choose an activity that

accommodates your

abilities

Physical Activity May Include

Lifting weights or

exercising with

elastic bands

Taking a tai chi or

senior yoga class

Dancing

Joining a local

senior exercise

class

How Do I Begin a Physical

Activity Session?

Warm up for 10 minutes

Use something sturdy for

support

Use a cane or walker during

activities

Exercise sitting

Consult a physical

therapist to help you

choose an activity

How Much Time Do I Need to

be Active For?

How Much Time Do I Need to

Be Active For?

Warm-up should be followed by at

least 30 minutes of effortful physical

activity.

30 - 60 minutes a day of endurance,

strengthening, balance and flexibility

activities

38

9/10/2013

How Much Effort is Needed?

Begin slowly and

pace yourself.

How Do I Finish a Physical

Activity?

Finish your session with a 10

minute cool down and a tall

glass of water.

You should be able

to carry on a

conversation during

the activity.

How Many Days A Week

Should I Be Active?

How might I expect to feel?

Try to do 3x per week, more can be better

7

5

When you first begin a physical

activity program or advance your

current activities it is normal to feel:

Mild muscle stiffness, burning, or

fatigue that decreases in 24 hours

Mild increase in heart rate with

continued activity, but that returns to

normal in 5 minutes

3

1

Stop to Rest if You Experience

Shortness of breath

(cant complete sentence)

Dizziness

Heart rate that exceeds prescribed

target rate

Onset or worsening of pain

Chest pain

What Does Progress Look

Like?

Minor improvement

in 2-3 weeks

Significant improvement in 2-3

months

Can lead to improved

Lifestyle and function!

39

9/10/2013

Lifetime Goals:

Maintaining Fitness Level

Getting Back on Track

10% per week

Illness

Vacation

Injury

Lose gains

missed

Effort

Resume

when you

can

Speed

Be realistic

Be consistent

Find a buddy

Journal / chart progress

Distance

Pearls of Wisdom

Will you be

running a mini

when you are

82?

Summary

Aerobic/cardiovascular endurance

Substantial improvements in almost all

aspects of CV function

Muscular strength

Individuals of all ages and disease states

can benefit from PRE

Can help maintain independence

Balance and coordination

Prevents falls, improves gait

Other

Muscle training can hypertrophy

remaining Muscle fibers thereby

decreasing the Fat to Muscle ratio

Lower extremity muscle strength is

affected greater than upper strength

Remaining muscle still have endurance

unless co-morbidity is present

Strength training will improve balance

and decrease fall risk

Summary

Improved max aerobic capacity

Increased max voluntary ventilation

Greater A-VO2 difference and stroke

volume

Lowered vascular resistance

Increased muscle strength (slow and

reverse decline)

Reduced involutional bone loss

Increased bone mineral content

improves mental function, bone health

40

9/10/2013

Summary

Decreased body fat/increased lean

body mass

Improved glucose tolerance

Lower lipid concentrations &

elevated HDL

Improved flexibility

Improved balance

Decreased risk for falls

Improved functional performance

41

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Wearable Motion Sensors To Continuously Measure Realworld ActivitiesDocument12 pagesWearable Motion Sensors To Continuously Measure Realworld ActivitiesshivnairNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Wearable Sensors For Reliable Fall DetectionDocument4 pagesWearable Sensors For Reliable Fall DetectionshivnairNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Human Activity Monitoring With Wearable SensorsDocument9 pagesHuman Activity Monitoring With Wearable SensorsshivnairNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Low Cost Accelerometer SensorsDocument11 pagesLow Cost Accelerometer SensorsshivnairNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Wearable Sensors For Remote Healthcare Monitoring SystemDocument6 pagesWearable Sensors For Remote Healthcare Monitoring SystemshivnairNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Electronics Artists Photo Theremin AmplifierDocument5 pagesElectronics Artists Photo Theremin AmplifiershivnairNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Detecting Vital Signs With Wearable Wireless SensorsDocument27 pagesDetecting Vital Signs With Wearable Wireless SensorsshivnairNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Wearable Biosensors Presentation SummaryDocument9 pagesWearable Biosensors Presentation SummaryshivnairNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- An Amulet For Trustworthy Wearable MHealthDocument6 pagesAn Amulet For Trustworthy Wearable MHealthshivnairNo ratings yet

- Smart Wearable Body Sensors For Patient Self-Assessment and MonitoringDocument9 pagesSmart Wearable Body Sensors For Patient Self-Assessment and MonitoringshivnairNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Current Progress On Pathological Tremor Modeling and ActiveDocument6 pagesCurrent Progress On Pathological Tremor Modeling and ActiveshivnairNo ratings yet

- WOW - The World of WearablesDocument1 pageWOW - The World of WearablesshivnairNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Wearable Sensor Systems and Their Impact On Biomedical Engineering - Paolo BonatoDocument3 pagesWearable Sensor Systems and Their Impact On Biomedical Engineering - Paolo BonatoshivnairNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Occupational Therapy and Dementia-Specific ToolsDocument14 pagesOccupational Therapy and Dementia-Specific ToolsshivnairNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Life and Work in Shakespeare's PoemsDocument36 pagesLife and Work in Shakespeare's PoemsshivnairNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Rotary MotionDocument17 pagesRotary MotionshivnairNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Textile-Based Wearable Sensors For Assisting Sports PerformanceDocument5 pagesTextile-Based Wearable Sensors For Assisting Sports PerformanceshivnairNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- Lessons in ElocutionDocument418 pagesLessons in ElocutionaquabuckNo ratings yet

- Analytics Reading ListDocument2 pagesAnalytics Reading ListshivnairNo ratings yet

- Cleaning & Disinfection Decontamination GuideDocument1 pageCleaning & Disinfection Decontamination GuideshivnairNo ratings yet

- Lectures On Political EconomyDocument69 pagesLectures On Political EconomyshivnairNo ratings yet

- Analytical Survey of Wearable SensorsDocument6 pagesAnalytical Survey of Wearable SensorsshivnairNo ratings yet

- The Auschwitz ProtocolDocument28 pagesThe Auschwitz ProtocolshivnairNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Predicting Cognitive Impairment in PDDocument292 pagesPredicting Cognitive Impairment in PDshivnairNo ratings yet

- Caudill 2008 Review of Sports HerniasDocument44 pagesCaudill 2008 Review of Sports HerniasshivnairNo ratings yet

- Fitness CountsDocument50 pagesFitness CountsLogan RunNo ratings yet

- What Cognitive Abilities Are Involved in Trail-Making PerformanceDocument27 pagesWhat Cognitive Abilities Are Involved in Trail-Making PerformanceshivnairNo ratings yet

- PDHBRev 09 Repr 10Document44 pagesPDHBRev 09 Repr 10dragonwNo ratings yet

- Scoliosis - Searching For The SpineDocument10 pagesScoliosis - Searching For The SpineshivnairNo ratings yet

- Cervical Cancer Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesCervical Cancer Literature Reviewaflskeqjr100% (1)

- Jadwal OktoberDocument48 pagesJadwal OktoberFerbian FakhmiNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Low Cost Portable Ventilator DesignDocument8 pagesLow Cost Portable Ventilator DesignRashmi SinghNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Homoeopathic Therapeutics in The Management of Childhood Autism DisorderDocument13 pagesEffectiveness of Homoeopathic Therapeutics in The Management of Childhood Autism DisorderShubhanshi BhasinNo ratings yet

- CHC VisitDocument48 pagesCHC VisitRamyasree BadeNo ratings yet

- Types and Causes of Phobias ExplainedDocument24 pagesTypes and Causes of Phobias ExplainedDebjyoti BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Pathfit-1 2Document34 pagesPathfit-1 2Lathea Daiser TheaNise TesalunaNo ratings yet

- Esophageal CancerDocument3 pagesEsophageal CancerChanthorn SokNo ratings yet

- Prenatal CareDocument16 pagesPrenatal CareMark MaNo ratings yet

- Etiology of Eating DisorderDocument5 pagesEtiology of Eating DisorderCecillia Primawaty100% (1)

- The Complete Enema Guide: by Helena BinghamDocument10 pagesThe Complete Enema Guide: by Helena BinghamJ.J.No ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- CNS Drug StudyDocument4 pagesCNS Drug StudyMAHUSAY JOYCE CARINANo ratings yet

- PYQDocument2 pagesPYQAisyah OthmanNo ratings yet

- Case Study CKD DM Type 2Document7 pagesCase Study CKD DM Type 2Brian Cornel0% (3)

- Internal Medicine Mar 2022Document8 pagesInternal Medicine Mar 2022Sanielle Karla Garcia LorenzoNo ratings yet

- APA Eating Disorders Practice Guideline Under CopyeditingDocument139 pagesAPA Eating Disorders Practice Guideline Under CopyeditingIbrahim NasserNo ratings yet

- C105a Pre-Sea and Periodic Medical Fitness Examinations For SeafarersDocument4 pagesC105a Pre-Sea and Periodic Medical Fitness Examinations For SeafarersAbu ShabeelNo ratings yet

- Physical Education: Quarter 2 - Module 1: Strengths and Weaknesses in Skill-Related Fitness ActivitiesDocument19 pagesPhysical Education: Quarter 2 - Module 1: Strengths and Weaknesses in Skill-Related Fitness ActivitiesJoshua DoradoNo ratings yet

- AHA-ASA Guideline For Adult Stroke Rehab and RecoveryDocument73 pagesAHA-ASA Guideline For Adult Stroke Rehab and RecoveryAfifaFahriyaniNo ratings yet

- Acute Stroke TreatmentDocument77 pagesAcute Stroke TreatmentRohitUpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Phylum Class Order Genera: Apicomplexa Haematozoa Haemosporida Plasmodium Piroplasmida Coccidia EimeriidaDocument39 pagesPhylum Class Order Genera: Apicomplexa Haematozoa Haemosporida Plasmodium Piroplasmida Coccidia EimeriidaMegbaruNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Surgical Treatment of Esophageal Achalasia PDFDocument24 pagesGuidelines For The Surgical Treatment of Esophageal Achalasia PDFInomy ClaudiaNo ratings yet

- 1 - Spirometry Simplified With CRF's PEFR PDFDocument80 pages1 - Spirometry Simplified With CRF's PEFR PDFyayatiNo ratings yet

- Division of Tropical Medicine and Infectious Diseases at Gatot Soebroto Central Army HospitalDocument63 pagesDivision of Tropical Medicine and Infectious Diseases at Gatot Soebroto Central Army HospitalAggiFitiyaningsihNo ratings yet

- Brain: What Is A Subarachnoid Hemorrhage?Document4 pagesBrain: What Is A Subarachnoid Hemorrhage?Rashellya RasyidaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Management A. Nursing Care PlanDocument12 pagesNursing Management A. Nursing Care Planmabzbutterfly69% (13)

- HomeopathyDocument33 pagesHomeopathyPriya Illakkiya100% (2)

- Nursing Care Plan For "Herniated Nucleus Pulposus Ruptured Inter Vertebral Disc"Document9 pagesNursing Care Plan For "Herniated Nucleus Pulposus Ruptured Inter Vertebral Disc"jhonroks100% (7)

- Cardiovascular Physiology Applied To Critical Care and AnesthesiDocument12 pagesCardiovascular Physiology Applied To Critical Care and AnesthesiLuis CortezNo ratings yet

- Discharge PlanDocument2 pagesDischarge Plankim arrojado100% (1)

- The Yogi Code: Seven Universal Laws of Infinite SuccessFrom EverandThe Yogi Code: Seven Universal Laws of Infinite SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (104)

- Chakras and Yoga: Finding Inner Harmony Through Practice, Awaken the Energy Centers for Optimal Physical and Spiritual Health.From EverandChakras and Yoga: Finding Inner Harmony Through Practice, Awaken the Energy Centers for Optimal Physical and Spiritual Health.Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Boundless: Upgrade Your Brain, Optimize Your Body & Defy AgingFrom EverandBoundless: Upgrade Your Brain, Optimize Your Body & Defy AgingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (66)

- Yamas & Niyamas: Exploring Yoga's Ethical PracticeFrom EverandYamas & Niyamas: Exploring Yoga's Ethical PracticeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- Wall Pilates: Quick-and-Simple to Lose Weight and Stay Healthy. A 30-Day Journey with + 100 ExercisesFrom EverandWall Pilates: Quick-and-Simple to Lose Weight and Stay Healthy. A 30-Day Journey with + 100 ExercisesNo ratings yet

- Functional Training and Beyond: Building the Ultimate Superfunctional Body and MindFrom EverandFunctional Training and Beyond: Building the Ultimate Superfunctional Body and MindRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1)

- Strong Is the New Beautiful: Embrace Your Natural Beauty, Eat Clean, and Harness Your PowerFrom EverandStrong Is the New Beautiful: Embrace Your Natural Beauty, Eat Clean, and Harness Your PowerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)