Professional Documents

Culture Documents

15 PDF

Uploaded by

Jhan JhanelleOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

15 PDF

Uploaded by

Jhan JhanelleCopyright:

Available Formats

:L\cpul.

Jlic of t{Jc

~npreme

i~hilippnu:l)

([oHrt

;t:bnila

.JUANITA ERMITANO, represented

by her Attorney-in-Fact) TSA BELO

ERMITANO,

Petitioner,

-versus -

hiEf',JDOZA, and

l"EONE1'J_ Jt.

Promulgated:

DECISION

PERALTA,J.:

Before the Court is a: petition for rcvi~:.:v,r on cc:nior{lr/ lllh hc:r l~ 11 k: -I~;

1

of the Rules of Comi seeking to reverse and ser aside the lkcisi(!tl dl~<l

Resolution 2 dated September 8, :?.004 and August 16, .2006, respecti,/cly, r;t'

the Court of APt-eals (CA) in CA-G.R. SP No. 77617.

On November 5, 1999, herein respondent and petitioner, 1hrough IH.::r

representative,, lsabelo R. Ermitano, executed a Contract of I c<~St:: wher,~in

petitioner leased in favor of respondent a 336 square meter residential lui

and a house standing thereon located at No. :?.0 Columbia St , Phase l, I )oi'1a

Vicenta Village, Davao City. The contract period is one ( I ) year, \\ llich

commenced on November 4, 1999, \Vith a nwnlhly rental nllc off! 13,Son no.

Pursuant to the contract, respondent paid petitioner P~7,000 00 as sct:uriry

deposit to answer for unpaid rentals and damage that nta~/ be cause.! It) the

leased unit.

Penned by Associate Justice A11uro G. Tayag, \\'itb Associate Justices Estt:la [\ 1 Pcrl<lo-l:kmaLc

(now a member of this Court) and Edgardo A. Camello concunint2,; Annex "A" to Petition, w/f,,. pp )(}-)()

2

Penned by Associate Justice Edgardo A. Camello, with .\ssuciatt Justices Ricardu R. lio,<lrlu diHI

Mario V. Lopez concurring; Annex "B" to Petition, rollo, pp. 60-61.

Decision

-2-

G.R. No. 174436

Subsequent to the execution of the lease contract, respondent received

information that sometime in March 1999, petitioner mortgaged the subject

property in favor of a certain Charlie Yap (Yap) and that the same was

already foreclosed with Yap as the purchaser of the disputed lot in an extrajudicial foreclosure sale which was registered on February 22, 2000. Yap's

brother later offered to sell the subject property to respondent. Respondent

entertained the said offer and negotiations ensued. On June 1, 2000,

respondent bought the subject property from Yap for P950,000.00. A Deed of

Sale of Real Property was executed by the parties as evidence of the

contract. However, it was made clear in the said Deed that the property was

still subject to petitioner's right of redemption.

Prior to respondent's purchase of the subject property, petitioner filed

a suit for the declaration of nullity of the mortgage in favor of Yap as well as

the sheriff's provisional certificate of sale which was issued after the

disputed house and lot were sold on foreclosure.

Meanwhile, on May 25, 2000, petitioner sent a letter demanding

respondent to pay the rentals which are due and to vacate the leased

premises. A second demand letter was sent on March 25, 2001. Respondent

ignored both letters.

On August 13, 2001, petitioner filed with the Municipal Trial Court in

Cities (MTCC), Davao City, a case of unlawful detainer against respondent.

In its Decision dated November 26, 2001, the MTCC, Branch 6,

Davao City dismissed the case filed by petitioner and awarded respondent

the amounts of P25,000.00 as attorney's fees and P2,000.00 as appearance

fee.

Petitioner filed an appeal with the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of

Davao City.

On February 14, 2003, the RTC rendered its Decision, the dispositive

portion of which reads as follows:

WHEREFORE, PREMISES CONSIDERED, the assailed Decision

is AFFIRMED with MODIFICATION. AFFIRMED insofar as it dismissed

the case for unlawful detainer but modified in that the award of attorney's

fees in defendant's [herein respondent's] favor is deleted and that the

defendant [respondent] is ordered to pay plaintiff [herein petitioner] the

equivalent of ten months unpaid rentals on the property or the total sum of

P135,000.00.

SO ORDERED.3

3

Rollo, p. 66.

Decision

-3-

G.R. No. 174436

The RTC held that herein respondent possesses the right to redeem the

subject property and that, pending expiration of the redemption period, she is

entitled to receive the rents, earnings and income derived from the property.

Aggrieved by the Decision of the RTC, petitioner filed a petition for

review with the CA.

On September 8, 2004, the CA rendered its assailed Decision

disposing, thus:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the assailed Decision of the

Regional Trial Court, Branch 16, 11th Judicial Region, Davao City is

AFFIRMED with the MODIFICATIONS as follows:

(a) Private respondent's obligation to pay the

petitioner the amount of ONE HUNDRED THIRTY-FIVE

THOUSAND PESOS (P135,000.00) equivalent of ten (10)

months is hereby DELETED;

(b) Attorney's fees and litigation expenses were

correctly awarded by the trial court having compelled the

private respondent to litigate and incur expenses to protect

her interests by reason of the unjustified act of petitioner

(Producers Bank of the Philippines vs. Court of Appeals,

365 SCRA 326), Thus: litigation expenses of only TEN

THOUSAND PESOS (P10,000.00) not TWENTY-FIVE

THOUSAND PESOS (P25,000.00); and

(c) Attorney's fees REINSTATED in the amount of

TEN THOUSAND PESOS (P10,000.00) instead of only

TWO THOUSAND PESOS (P2,000.00).

SO ORDERED.4

Quoting extensively from the decision of the MTCC as well as on

respondent's comment on the petition for review, the CA ruled that

respondent did not act in bad faith when she bought the property in question

because she had every right to rely on the validity of the documents

evidencing the mortgage and the foreclosure proceedings.

Petitioner filed a Motion for Reconsideration, but the CA denied it in

its Resolution dated August 16, 2006.

Hence, the instant petition for review on certiorari raising the

following assignment of errors:

Id. at 57-58. (Emphasis in the original)

Decision

-4-

G.R. No. 174436

A.WHETHER OR NOT THE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN

DISMISSING THE UNLAWFUL DETAINER CASE BY RULING THAT

A SHERIFF'S FINAL CERTIFICATE OF SALE WAS ALREADY

ISSUED WHICH DECISION IS NOT BASED ON THE EVIDENCE

AND IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE APPLICABLE LAWS AND

JURISPRUDENCE.

B. WHETHER OR NOT THE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED

WHEN IT RULED THAT PRIVATE RESPONDENT WAS A BUYER IN

GOOD FAITH EVEN IF SHE WAS INFORMED BY PETITIONER

THROUGH A LETTER ADVISING HER THAT THE REAL ESTATE

MORTGAGE CONTRACT WAS SHAM, FICTITIOUS AS IT WAS A

PRODUCT OF FORGERY BECAUSE PETITIONER'S PURPORTED

SIGNATURE APPEARING THEREIN WAS SIGNED AND FALSIFIED

BY A CERTAIN ANGELA CELOSIA.

C. WHETHER OR NOT THE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED

WHEN IT AWARDED ATTORNEY'S FEES WHICH WAS DELETED

BY RTC-BRANCH 16 OF DAVAO CITY DESPITE THE ABSENCE OF

ANY EXPLANATION AND/OR JUSTIFICATION IN THE BODY OF

THE DECISION.5

At the outset, it bears to reiterate the settled rule that the only question

that the courts resolve in ejectment proceedings is: who is entitled to the

physical possession of the premises, that is, to the possession de facto and

not to the possession de jure.6 It does not even matter if a party's title to the

property is questionable.7 In an unlawful detainer case, the sole issue for

resolution is the physical or material possession of the property involved,

independent of any claim of ownership by any of the party litigants.8 Where

the issue of ownership is raised by any of the parties, the courts may pass

upon the same in order to determine who has the right to possess the

property.9 The adjudication is, however, merely provisional and would not

bar or prejudice an action between the same parties involving title to the

property.10

In the instant case, pending final resolution of the suit filed by

petitioner for the declaration of nullity of the real estate mortgage in favor of

Yap, the MTCC, the RTC and the CA were unanimous in sustaining the

presumption of validity of the real estate mortgage over the subject property

in favor of Yap as well as the presumption of regularity in the performance

of the duties of the public officers who subsequently conducted its

foreclosure sale and issued a provisional certificate of sale. Based on the

presumed validity of the mortgage and the subsequent foreclosure sale, the

MTCC, the RTC and the CA also sustained the validity of respondent's

purchase of the disputed property from Yap. The Court finds no cogent

5

6

7

8

9

10

Id. at 21.

Barrientos v. Rapal, G.R. No. 169594, July 20, 2011, 654 SCRA 165, 170.

Id. at 170-171.

Id. at 171.

Id.

Id.

Decision

-5-

G.R. No. 174436

reason to depart from these rulings of the MTCC, RTC and CA. Thus, for

purposes of resolving the issue as to who between petitioner and respondent

is entitled to possess the subject property, this presumption stands.

Going to the main issue in the instant petition, it is settled that in

unlawful detainer, one unlawfully withholds possession thereof after the

expiration or termination of his right to hold possession under any contract,

express or implied.11 In such case, the possession was originally lawful but

became unlawful by the expiration or termination of the right to possess;

hence, the issue of rightful possession is decisive for, in such action, the

defendant is in actual possession and the plaintiffs cause of action is the

termination of the defendants right to continue in possession.12

In the instant petition, petitioner's basic postulate in her first and

second assigned errors is that she remains the owner of the subject property.

Based on her contract of lease with respondent, petitioner insists that

respondent is not permitted to deny her title over the said property in

accordance with the provisions of Section 2 (b), Rule 131 of the Rules of

Court.

The Court does not agree.

The conclusive presumption found in Section 2 (b), Rule 131 of the

Rules of Court, known as estoppel against tenants, provides as follows:

Sec. 2. Conclusive presumptions. The following are instances of

conclusive presumptions:

xxxx

(b) The tenant is not permitted to deny the title of his landlord at

the time of the commencement of the relation of landlord and tenant

between them. (Emphasis supplied).

It is clear from the abovequoted provision that what a tenant is

estopped from denying is the title of his landlord at the time of the

commencement of the landlord-tenant relation.13 If the title asserted is one

that is alleged to have been acquired subsequent to the commencement of

that relation, the presumption will not apply.14 Hence, the tenant may show

that the landlord's title has expired or been conveyed to another or himself;

and he is not estopped to deny a claim for rent, if he has been ousted or

evicted by title paramount.15 In the present case, what respondent is claiming

11

12

13

14

15

Union Bank of the Philippines v. Maunlad Homes, Inc., G.R. No. 190071, August 15, 2012.

Malabanan v. Rural Bank of Cabuyao, Inc., G.R. No. 163495, May 8, 2009, 587 SCRA 442, 448.

Santos v. National Statistics Office, G.R. No. 171129, April 6, 2011, 647 SCRA 345, 357.

Id.

Id.

Decision

-6-

G.R. No. 174436

is her supposed title to the subject property which she acquired subsequent

to the commencement of the landlord-tenant relation between her and

petitioner. Hence, the presumption under Section 2 (b), Rule 131 of the

Rules of Court does not apply.

The foregoing notwithstanding, even if respondent is not estopped

from denying petitioner's claim for rent, her basis for such denial, which is

her subsequent acquisition of ownership of the disputed property, is

nonetheless, an insufficient excuse from refusing to pay the rentals due to

petitioner.

There is no dispute that at the time that respondent purchased Yap's

rights over the subject property, petitioner's right of redemption as a

mortgagor has not yet expired. It is settled that during the period of

redemption, it cannot be said that the mortgagor is no longer the owner of

the foreclosed property, since the rule up to now is that the right of a

purchaser at a foreclosure sale is merely inchoate until after the period of

redemption has expired without the right being exercised.16 The title to land

sold under mortgage foreclosure remains in the mortgagor or his grantee

until the expiration of the redemption period and conveyance by the master's

deed.17 Indeed, the rule has always been that it is only upon the expiration of

the redemption period, without the judgment debtor having made use of his

right of redemption, that the ownership of the land sold becomes

consolidated in the purchaser.18

Stated differently, under Act. No. 3135, the purchaser in a foreclosure

sale has, during the redemption period, only an inchoate right and not the

absolute right to the property with all the accompanying incidents.19 He only

becomes an absolute owner of the property if it is not redeemed during the

redemption period.20

Pending expiration of the period of redemption, Section 7 of Act No.

3135, as amended, provides:

21

Sec. 7. In any sale made under the provisions of this Act, the

purchaser may petition the Court of First Instance of the province or place

where the property or any part thereof is situated, to give him possession

thereof during the redemption period, furnishing bond in an amount

16

Serrano v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 133883, December 10, 2003, 417 SCRA 415, 428; 463 Phil.

77, 91 (2003); Medida v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 98334, May 8, 1992, 208 SCRA 887, 897.

17

Medida v. Court of Appeals, supra.

18

St. James College of Paraaque v. Equitable PCI Bank, G.R. No. 179441, August 9, 2010, 627

SCRA 328, 348-349.

19

Sta. Ignacia Rural Bank, Inc. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 97872, March 1, 1994, 230 SCRA 513,

524.

20

Id.

21

An Act to Regulate the Sale of Property Under Special Powers Inserted In or Annexed to Real

Estate Mortgages.

Decision

-7-

G.R. No. 174436

equivalent to the use of the property for a period of twelve months, to

indemnify the debtor in case it be shown that the sale was made without

violating the mortgage or without complying with the requirements of this

Act. Such petition shall be made under oath and filed in [the] form of an ex

parte motion in the registration or cadastral proceedings if the property is

registered, or in special proceedings in the case of property registered

under the Mortgage Law or under section one hundred and ninety-four of

the Administrative Code, or of any other real property encumbered with a

mortgage duly registered in the office of any register of deeds in

accordance with any existing law, and in each case the clerk of the court

shall, upon the filing of such petition, collect the fees specified in

paragraph eleven of section one hundred and fourteen of Act Numbered

Four hundred and ninety-six, as amended by Act Numbered Twenty-eight

hundred and sixty-six, and the court shall, upon approval of the bond,

order that a writ of possession issue, addressed to the sheriff of the

province in which the property is situated, who shall execute said order

immediately.

Thus, it is clear from the abovequoted provision of law that, as a

consequence of the inchoate character of the purchaser's right during the

redemption period, Act. No. 3135, as amended, allows the purchaser at the

foreclosure sale to take possession of the property only upon the filing of a

bond, in an amount equivalent to the use of the property for a period of

twelve (12) months, to indemnify the mortgagor in case it be shown that the

sale was made in violation of the mortgage or without complying with the

requirements of the law. In Cua Lai Chu v. Laqui,22 this Court reiterated the

rule earlier pronounced in Navarra v. Court of Appeals23 that the purchaser

at an extrajudicial foreclosure sale has a right to the possession of the

property even during the one-year redemption period provided the

purchaser files an indemnity bond. That bond, nonetheless, is not required

after the purchaser has consolidated his title to the property following the

mortgagor's failure to exercise his right of redemption for in such a case, the

former has become the absolute owner thereof.24

It, thus, clearly follows from the foregoing that, during the period of

redemption, the mortgagor, being still the owner of the foreclosed property,

remains entitled to the physical possession thereof subject to the purchaser's

right to petition the court to give him possession and to file a bond pursuant

to the provisions of Section 7 of Act No. 3135, as amended. The mere

purchase and certificate of sale alone do not confer any right to the

possession or beneficial use of the premises.25

In the instant case, there is neither evidence nor allegation that

respondent, as purchaser of the disputed property, filed a petition and bond

22

G.R. No. 169190, February 11, 2010, 612 SCRA 227, 233.

G.R. No. 86237, December 17, 1991, 204 SCRA 850, 856.

24

Sta. Ignacia Rural Bank, Inc. v. Court of Appeals, supra note 19, at 525.

25

Gonzales v. Calimbas, G.R. No. L-27878, December 31, 1927, 51 SCRA 355, 358; 51 Phil. 355,

358 (1927).

23

Decision

-8-

G.R. No. 174436

in accordance with the provisions of Section 7 of Act No. 3135. In addition,

respondent defaulted in the payment of her rents. Thus, absent respondent's

filing of such petition and bond prior to the expiration of the period of

redemption, coupled with her failure to pay her rent, she did not have the

right to possess the subject property.

On the other hand, petitioner, as mortgagor and owner, was entitled

not only to the possession of the disputed house and lot but also to the rents,

earnings and income derived therefrom. In this regard, the RTC correctly

cited Section 32, Rule 39 of the Rules of Court which provides as follows:

Sec. 32. Rents, earnings and income of property pending

redemption. The purchaser or a redemptioner shall not be entitled to

receive the rents, earnings and income of the property sold on execution,

or the value of the use and occupation thereof when such property is in the

possession of a tenant. All rents, earnings and income derived from the

property pending redemption shall belong to the judgment obligor

until the expiration of his period of redemption. (Emphasis supplied)

While the above rule refers to execution sales, the Court finds no

cogent reason not to apply the same principle to a foreclosure sale, as in this

case.

The situation became different, however, after the expiration of the

redemption period on February 23, 2001. Since there is no allegation, much

less evidence, that petitioner redeemed the subject property within one year

from the date of registration of the certificate of sale, respondent became the

owner thereof. Consolidation of title becomes a right upon the expiration of

the redemption period.26 Having become the owner of the disputed property,

respondent is then entitled to its possession.

As a consequence, petitioner's ejectment suit filed against respondent

was rendered moot when the period of redemption expired on February 23,

2001 without petitioner having redeemed the subject property, for upon

expiration of such period petitioner lost his possessory right over the same.

Hence, the only remaining right that petitioner can enforce is his right to the

rentals during the time that he was still entitled to physical possession of the

subject property that is from May 2000 until February 23, 2001.

In this regard, this Court agrees with the findings of the MTCC that,

based on the evidence and the pleadings filed by petitioner, respondent is

liable for payment of rentals beginning May 2000 until February 2001, or for

a period of ten (10) months. However, it is not disputed that respondent

26

GC Dalton Industries, Inc. v. Equitable PCI Bank, G.R. No. 171169, August 24, 2009, 596 SCRA

723, 730.

Decision

already gave to petitioner the sum ofld27,000.00, v\'hicil i;:; '-o:quivcdenl hi t\\O

(2) months~ rental, as deposit to cover f()r <-irlY unpuid rcrtUd:;. It is 111dy

proper to deduct this amount from the rentals due Io pelilicJnu, tl!it~ leL~vittg

P 108,000.00 unpaid rentals.

As to attorney's fees and lirigauon expc:nsc:s, !he l'omt a~!"cts with tl1t:

RTC that since petitioner is, in fact, entilled to Wipai(lh:nttd~:>, l1u ,_,mq:lainl

which, among others, prays for rhe payment ol unpaid tY.::ntals, is p1:)Iilic:~,1

Thus, the award of attomey's and litigation expens,;s 1o re::>p(Hkklll :c.!tt~tdd h--

deleted.

WHEREFOHE, the Decision and Resc;luticn uf ll1c: Cuun .~t ~ppc;.ds

in CA-G.R. SP No. 77617, dated s~pternber d . .20(Fl cmd !\Uglt:.ll l h, ~()Ut;

respectively, are AFFlRIVIED IYilh the followi11g l\lOIHFIC.\TION~;: i l)

respondent is ORDERED to pay petitioner J11 118,noo (h) Lb and hH unpaid

rentals; (2) the av.rard of attorney's f~cs and litigation exp~:n~es tn te::,pnndclll

is DELETED.

SO ORDERED.

WE CONCUR:

/

A_ _

.'

'"'--.

'

PRESBITEH9 J. VELASCO, .H<.

Assocjate Justice

Chairperson

lJUM<~/

ROBERTO A. ABAD

Associate Justice

-)~

. .~~

.~/2/.

. /./"~

. -I;~~~~,/. ..l

~"""'l.J/"-...~

MARVIC J\1ARIO VICTOR F. LEONE~

Associate Justice

"

Decision

- 10 -

(iR. t"lu l 71cl )()

ATTI~ST~TION

I attest that the conclusions in the above Decision had been n.:a~:hed in

consultation before the case \~'as assigned to the \vriter of the opinion uf lh~:

Court's Division.

/

PHF.SBITEHq:J. VELASCO, JH.

Associate Justil~e

f

Clmirper~on, Third l)ivisi<m

CnTIFICATlOr~

Pursuant to Section 13, Anicle Vlll of the Cfll1stitutinn and !111:~

Division Chairperson's Attestation, [ cenii)' that the conclusions in the ah<we

Decision had been reached in consultation before the case was assigned to

the \vriter of the opinion of the Court's Di,.rision.

lVIAHlA LOURDES P. A.

Chief Justice

SEIU~NO

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Neil Garfield - Expert or Bozo?Document44 pagesNeil Garfield - Expert or Bozo?Bob Hurt50% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- PACER Terry Woods Vs Hudson Holdings, Avi Greenbaum & Steven MichaelDocument73 pagesPACER Terry Woods Vs Hudson Holdings, Avi Greenbaum & Steven Michaeljpeppard100% (1)

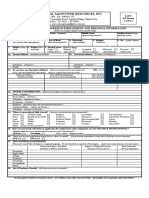

- Olive International Manpower Resources, Inc.: Application For Overseas Employment and Personal InformationDocument3 pagesOlive International Manpower Resources, Inc.: Application For Overseas Employment and Personal InformationJhan JhanelleNo ratings yet

- Forward Never Backward NeverDocument1 pageForward Never Backward NeverJhan JhanelleNo ratings yet

- Carrascoso JR V Court of Appeals and Lauro LevisteDocument4 pagesCarrascoso JR V Court of Appeals and Lauro LevisteJhan JhanelleNo ratings yet

- As They Say, EducationDocument1 pageAs They Say, EducationJhan JhanelleNo ratings yet

- 15 PDFDocument10 pages15 PDFJhan JhanelleNo ratings yet

- Land Patents and Foreclosures The TruthDocument2 pagesLand Patents and Foreclosures The TruthWilliam B.90% (10)

- ERIKA Case Digest Part II To Be Submitted On FEB 24Document5 pagesERIKA Case Digest Part II To Be Submitted On FEB 24Red HaleNo ratings yet

- Revised UCC Article 9 SummaryDocument11 pagesRevised UCC Article 9 SummaryJason Henry100% (2)

- Restore America Plan Declaration PagesDocument30 pagesRestore America Plan Declaration PagesLogisticsMonster100% (9)

- BPI Family Savings Bank Inc. v. Vda.Document19 pagesBPI Family Savings Bank Inc. v. Vda.paulineNo ratings yet

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondents: Second DivisionDocument6 pagesPetitioners vs. vs. Respondents: Second DivisionVener MargalloNo ratings yet

- DBP V CA 2Document6 pagesDBP V CA 2Jigs Iniego Sanchez SevilleNo ratings yet

- Bicol Savings and Loan Association vs. Hon. Court of AppealsDocument4 pagesBicol Savings and Loan Association vs. Hon. Court of AppealsPat RañolaNo ratings yet

- Filed Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of LawDocument44 pagesFiled Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Lawmichael-d-donovan-1299No ratings yet

- Commercial Law (Atty. M. Gapuz) PDFDocument8 pagesCommercial Law (Atty. M. Gapuz) PDFRhald KhoNo ratings yet

- Wayne County, Michigan Mortgage Foreclosure Sherrif Sales Order and Opinion 2:09-cv-14328-2Document16 pagesWayne County, Michigan Mortgage Foreclosure Sherrif Sales Order and Opinion 2:09-cv-14328-2Beverly TranNo ratings yet

- Medida Vs Court of Appeals (208 SCRA 887)Document2 pagesMedida Vs Court of Appeals (208 SCRA 887)Judy Miraflores Dumduma100% (3)

- Tongoy V CA (Digest)Document4 pagesTongoy V CA (Digest)André Jan Lee Cardeño0% (1)

- Ruby Shelter V Formaran Yap V PDCP Lapanday V Estita Piltelcom V TecsonDocument3 pagesRuby Shelter V Formaran Yap V PDCP Lapanday V Estita Piltelcom V TecsonEmi SicatNo ratings yet

- Real & Other Properties Acquired (Ropa) : Audit ObjectivesDocument1 pageReal & Other Properties Acquired (Ropa) : Audit ObjectivesIvoryBrigino100% (1)

- Alarilla V OcampoDocument3 pagesAlarilla V OcampoAllan ChuaNo ratings yet

- Pioneer Insurance & Surety Corporation vs. Court of Appeals: 668 Supreme Court Reports AnnotatedDocument12 pagesPioneer Insurance & Surety Corporation vs. Court of Appeals: 668 Supreme Court Reports AnnotatedAlexiss Mace JuradoNo ratings yet

- Pledge Annotation and CasesDocument15 pagesPledge Annotation and CasesAster Beane AranetaNo ratings yet

- FBI 18 USC 371 Fraud or Impairment of A Legitimate Government Activity RMS - MRLPDocument48 pagesFBI 18 USC 371 Fraud or Impairment of A Legitimate Government Activity RMS - MRLPNeil GillespieNo ratings yet

- AM No 00-8-10-SC - Rehab RulesDocument20 pagesAM No 00-8-10-SC - Rehab RulesJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- 149 China Banking V LozadaDocument4 pages149 China Banking V Lozadaangelo prietoNo ratings yet

- BankUnited Fraud - Albertelli Law S Wrongful Foreclosure ActionDocument22 pagesBankUnited Fraud - Albertelli Law S Wrongful Foreclosure ActionAlbertelli_LawNo ratings yet

- Lanuza Vs de LeonDocument4 pagesLanuza Vs de Leonlalisa lalisaNo ratings yet

- 13 United Overseas v. RosemooreDocument22 pages13 United Overseas v. RosemooreEdryd RodriguezNo ratings yet

- 06 Cavite Development Bank Vs SPS Lim, GR No. 131679, February 1, 2000Document11 pages06 Cavite Development Bank Vs SPS Lim, GR No. 131679, February 1, 2000Sarah Jean SiloterioNo ratings yet

- 5 and 10Document4 pages5 and 10ambahomoNo ratings yet

- Chieng V SP Santos - GR 169647Document17 pagesChieng V SP Santos - GR 169647Jeremiah ReynaldoNo ratings yet

- Digests 7Document10 pagesDigests 7KristineSherikaChyNo ratings yet