Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Binge Drinking

Uploaded by

Fati NovOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Binge Drinking

Uploaded by

Fati NovCopyright:

Available Formats

0145-6008/05/2903-0317$03.

00/0

ALCOHOLISM: CLINICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH

Vol. 29, No. 3

March 2005

Binge Drinking, Cognitive Performance and Mood in a

Population of Young Social Drinkers

Julia M. Townshend and Theodora Duka

Background: Binge drinking may lead to brain damage and have implications for the development of

alcohol dependence. The aims of the present study were to determine individual characteristics as well as

to compare mood states and cognitive function between binge and nonbinge drinkers and thus further

validate the new tool used to identify these populations among social drinkers.

Methods: The lowest and the highest 33.3% from a database of 245 social drinkers binge scores derived

from the Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ) were used as cutoff points to identify nonbinge drinkers and

binge drinkers in a further population of 100 young healthy volunteers. Personality characteristics, expectations of the effects of alcohol and current mood were evaluated. Cognitive performance was tested with

a Matching to Sample Visual Search task (MTS) and a Spatial Working Memory task (SWM) both from the

CANTAB battery, and a Vigilance task from the Gordon Diagnostic System.

Results: The binge drinkers had less positive mood than the nonbinge drinkers. In the MTS choice time on

an 8-pattern condition and movement time on an 8- and 4-pattern condition was found to be faster in the binge

drinkers compared to nonbinge drinkers. A gender by binge drinking interaction in the SWM and the Gordon

Diagnostic System task revealed that female binge drinkers were worse on both these tasks than the female

nonbinge drinkers.

Conclusions: These results confirm previous findings in binge drinkers and suggest that in a nondependent alcohol-drinking group, differences can be seen in mood and cognitive performance between those

that binge drink and those that do not.

Key Words: Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ), Impulsivity, Repeated Withdrawal, Gender, Frontal

Lobe.

INGE DRINKING IN young people is on the increase

in Britain (Morgan et al., 1999), the United States

(Naimi et al., 2003) and increasingly in developing countries throughout the world (Parry et al., 2002). In a student

population, binge drinking has been shown to predict the

frequency with which alcohol related problems are experienced (Wechsler et al., 1994) and Hunt (1993) has suggested that binge drinkers may be more at risk of developing brain damage. Binge ethanol exposure in adult rats has

been shown to cause necrotic neurodegeneration after as

little as 2 days of exposure (Obernier et al., 2002a). In

addition Crews and colleagues (Crews et al., 2000) have

found that young adolescent rats show differential patterns

of brain damage after binge ethanol treatment compared to

adult rats. The associated frontal cortical olfactory regions

were damaged only in the adolescent rats. Further animal

studies have provided evidence of increased brain damage

From Laboratory of Experimental Psychology, University of Sussex,

Falmer, Brighton.

Received for publication March 15, 2004; accepted December 13, 2004.

This work was supported by MRC Grant No. G9806260.

Reprint requests: Dr. Theodora Duka, Psychology, University of Sussex,

Falmer, Brighton BN1 9QG; Fax: 44 1273 678058; E-mail: t.duka@

sussex.ac.uk

Copyright 2005 by the Research Society on Alcoholism.

DOI: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000156453.05028.F5

Alcohol Clin Exp Res, Vol 29, No 3, 2005: pp 317325

after multiple withdrawals from alcohol or when repeatedly

high amounts of alcohol in the brain are followed by periods of abstinence (i.e., binge drinking; Crews et al., 2001;

Veatch and Gonzalez, 1999). Imaging studies on adolescents with alcohol use disorders have also provided evidence for brain abnormalities associated with the age at

onset of the alcohol use disorder (De Bellis et al., 2000).

It has been proposed that number of drinks in a row

differentiates binge drinkers from nonbinge drinkers

(Wechsler and Austin, 1998), and while this may be the

case it also means that binge drinkers and nonbinge drinkers will almost certainly consume different quantities of

alcohol. We have used a score (binge drinking score)

derived from items from an Alcohol Use Questionnaire

(Mehrabian and Russell, 1978) referring to drinking behavior and not to consumption and have compared it with the

measurement drinks in a row as described by Wechsler

and Austin (Wechsler and Austin, 1998). We have shown

that, unlike the measurement drinks in a row, the binge

drinking score was unrelated to weekly alcohol consumption (Townshend and Duka, 2002). Based on the proposal

that repeated withdrawal from alcohol may contribute to

the development of addiction (withdrawal sensitization

theory of addiction, Stephens, 1995) a binge score

founded on patterns of drinking rather than quantities of

317

318

alcohol consumed may be a better predictor of future

alcohol dependency problems.

A characteristic marker of binge drinking behavior is the

consumption of large amounts of alcohol within a limited

time period followed by a period of abstinence, as opposed

to regular drinking in which a person might consume similar weekly amounts of alcohol but without the extremes of

alcohol intoxication. Thus binge drinking can be considered

analogous to repeated withdrawal from alcohol, a behavior

that has been shown to affect both cognitive and emotional

responding in alcoholic inpatients (Duka et al., 2004; Duka

et al., 2002, 2003; Townshend and Duka, 2003). Such an

idea is based on extrapolation from animal studies that

have shown clearly binges of alcohol, like multiple withdrawals from alcohol, produce brain damage and cognitive

impairments (Duka et al., 2004; Obernier et al., 2002b;

Ripley et al., 2003; Stephens et al., 2001).

In alcoholics several morphological abnormalities in the

frontal lobe system have been reported (for a review, see

Moselhy et al., 2001), and we have recently found that

alcoholic patients with two or more previous experiences of

medically supervised detoxifications from alcohol were

more impaired than patients with a single, or no previous

experience of detoxification in tasks measuring frontal lobe

function. Given these results it is possible that binge drinking behavior in young healthy adults might also affect

performance on such tasks. We have therefore included a

task that measures the ability to disinhibit a prepotent

response (the Vigilance task in the Gordon Diagnostic

System). In a previous study that looked at the effects of

alcohol on frontal lobe tasks we have found in a posthoc

analysis that binge drinkers made more between search

errors and had a worse strategy in a task that measures

spatial working memory compared to nonbinge drinkers.

To replicate these findings in a prospective study we have

also added the Spatial Working Memory task from the

CANTAB battery in the present study. In addition we have

included a measure of visual search speed that can reveal

impulsivity, a behavioral trait often cited as an important

behavioral predictor of excessive alcohol consumption.

Such a measure will provide information about a cognitive

impairment that might have preceded the binge drinking

behavior. However, we are aware that unless a prospective

study is carried out with adolescents before and after they

have indulged into binge drinking behavior, a clear distinction of what cognitive impairment preceded and what followed as a result of binge drinking is not possible.

Traditionally more of a male activity, binge drinking is

now increasing in females. In a recent study, reported cases

of blackouts were as high in females as in males leading to

increasingly risky behavior in terms of personal safety

(White et al., 2002). However whether the consequences of

binge drinking behavior are different between males and

females is not yet known. Consequently, in this study, we

will be looking at gender differences in performance on

impulsivity and frontal lobe tasks.

TOWNSHEND AND DUKA

The grouping of binge drinkers in this study was based on

a database of 245 Alcohol Use Questionnaires (AUQ;

Mehrabian and Russell, 1978) completed by volunteers. A

binge drinking score was calculated for each individual

using the three questions from the AUQ evaluating drinking patterns (drinks per hour; times drunk within the last 6

months; % of being drunk when drinking) and excluding

weekly alcohol consumption. The lowest and the highest

33.3% were grouped as nonbinge drinkers and binge drinkers respectively. The maximum score of the nonbinge

drinking group and the minimum score of the bingedrinking group from the 245 social drinkers were used as

cutoff points to identify binge drinkers and nonbinge drinkers in this current study population. As the binge drinking

score is based on patterns of drinking rather than quantity

consumed, we did not find differences between the binge

drinking scores of males and females in our sample of social

drinkers. Consequently, the same cutoff points were used

for male and female volunteers.

There is evidence that greater positive alcohol expectancies are associated with binge drinking episodes (Blume et

al., 2003). Also peer influence can have a strong impact on

drinking behavior. It has previously been shown that sibling

smoking was one of the strongest predictors of smoking

behavior in adolescents (Wilkinson and Abraham, 2004).

Personality (temperament) traits like high Harm Avoidance, as measured by the Temperament and Character

Inventory (TCI; Cloninger et al., 1994) have been associated with binge drinking (Gilligan et al., 1987). On the

other hand aspects of impulsivity and an early age of starting drinking have been associated with high Novelty Seeking also measured by the TCI. We have therefore included

an Alcohol Outcome Expectancy Questionnaire and the

TCI in the present study. These latter measures therefore

will provide information about trait characteristics which

may predispose to binge drinking. In a previous study we

have also found that alcoholic patients who have experienced two or more detoxifications presented with high

ratings of feelings of anger compared with their counterparts with no previous detoxifications (Duka et al., 2002).

Thus the present study was designed to look at the relationship between patterns of drinking behavior, cognitive

performance, mood, expectancies from alcohol, and personality characteristics. The role of gender was also

examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

One hundred young, healthy volunteers (50 male and 50 female)

moderate to heavy social drinkers between the ages of 18 and 30 (mean

20.9, SD 2.6) answered an advertisement for social drinkers to take part in

a study looking at the relationship between performance on cognitive tasks

and drinking patterns. Volunteers with current symptoms or a history of

mental illness, neurological diseases, drug or alcohol dependence were not

included in the study. Participants had been instructed to abstain from the

use of illicit recreational drugs for at least 1 week prior to the experiment,

BINGE DRINKING, MOOD AND COGNITION

from the use of sleeping tablets or hay fever medication for at least 48 hr,

and from the use of alcohol for at least 12 hr prior to the experiment. It

was discovered at the data input stage that one female had participated

twice in the study so her second data set was discarded leaving 99 participants. Those who drank 6 units or less per week [3 glasses of wine or 2.5

pints lager (3 drinks)] were excluded, as by any definition they could not

have been binge drinkers (i.e., even if they had the drinks in a row there

would have been less than 4 drinks in a row). Two females were lost by this

exclusion leaving 50 male participants and 47 female participants in total.

All except 4 spoke English as their first language. The National Adult

Reading Test (NART) scores from these 4, and 1 dyslexic volunteer were

discarded. The study was approved by the University of Sussex Ethical

Committee and all volunteers gave their informed consent and were paid

for their time at a rate of approximately 5 per hour.

Demographics

Population characteristics were based on information obtained from

the participants and included smoking information and the quantity and

time of their most recent alcoholic drink and caffeinated product.

Questionnaires

I. Alcohol and Drug Use

Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ). A quantity-frequency, beveragespecific index of alcohol consumption for the previous 6 months was

obtained using a revised version of the Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ;

Mehrabian and Russell, 1978). The revised questions, by determining

brands of liquor, allow for actual alcoholic content (percentage volume) of

drinks to be assessed. Participants were asked to estimate the number of

drinking days, the usual quantity consumed and the pattern of drinking.

We have previously demonstrated that the AUQ is a reliable measure of

drinking quantity and drinking pattern (Townshend and Duka, 2000).

Binge drinking score. A binge drinking score was calculated for all

participants on the basis of the information given in items 10, 11, and 12 of the

AUQ [Speed of drinking (average drinks per hour); number of times being

drunk in the previous 6 months; percentage of times getting drunk when

drinking (average)]. The binge score is calculated in the same way as the

AUQ score is derived but without the items 1 9 that refer to quantity and

type of alcohol intake: [4 (Item 10) Item 11 0.2 (Item 12);

Mehrabian and Russell, 1978]. This score gives a picture of the drinking

patterns of the participants rather than just a measure of alcohol intake.

Participants who have a high binge score and drink frequently but irregularly may have a similar intake of alcohol to those with a lower binge score

who drink on a regular basis. The cutoff points of the binge score for

separating binge drinkers from nonbinge drinkers was binge score 16 for

non binge drinkers and binge score 24 for binge drinkers. Subjects with

scores in between were considered not classifiable.

Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire (AEQ). Based on the Comprehensive

Effects of Alcohol Questionnaire (CEOA; Fromme et al., 1993), the AEQ

is a 38-item questionnaire, which assesses positive and negative expected

effects of alcohol consumption. There are seven expectancy factors, four

positive (sociability, tension reduction, liquid courage and sexuality), and

three negative (cognitive and behavioral impairments, risk and aggression,

and negative self perception).

Structured Interview Questionnaire revised (SIQ-R). The Structured

Interview Questionnaire has previously been used to evaluate the drinking

habits of an alcoholic population (Duka et al., 2002). A revised version was

constructed for the healthy volunteers in the current study that asked

about age of starting drinking, family history of alcoholism and sibling

alcohol / drug use. A family history score was derived by giving a score of

2 points for each first degree relative and 1 point for each second degree

relative. Participants were asked to estimate as best they could their

siblings weekly alcohol and/or drug use. For the analysis the amount of

alcohol or drug use was taken for the sibling (same or opposite sex) of

nearest age to the participant provided they were more than 16 years old.

Drug Use Questionnaire. This questionnaire asks for duration of use,

time since last use, how often used and dose per session for all the main

319

drug categories. For the purposes of this study as a rough guide to drug

use, participants were given a score in which 0 no drug use; 1

occasional use of cannabis/hash or marijuana; 2 regular use of cannabis/

hash or marijuana (at least once a week); 3 use of ecstasy and/or other

drugs.

II. Trait Measurements

The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) (Cloninger et al.,

1994) is a 240-item personality questionnaire designed to assess individual

differences on 4 measures of temperament and 3 measures of character.

The temperament measures, which represent hereditary traits, are novelty

seeking, harm avoidance, reward dependence, and persistence. The character measures, which represent acquired traits, are self-directedness,

cooperativeness, and self-transcendence. The TCI was always given at the

end of the testing session.

III. Current Mood Measures

Profile of Mood States (POMS; McNair et al., 1971). The POMS consists

of 72 mood related adjectives which participants are instructed to rate on

a 5-point scale ranging from not at all (0) to extremely (4). Through

the process of factor analysis 8-factors have been established: Anxiety,

Fatigue, Depression, Anger, Vigor, Confusion, Friendliness, and Elation.

In addition, two further composite factors can be derived as follows:

Arousal (Anxiety Vigor) (Fatigue Confusion), and Positive

Mood Elation Depression (de Wit and Doty, 1994). All 10 factors

were evaluated for this study.

The questionnaires and the Vigilance task for adults from the Gordon

Diagnostic System (see below) were given in random order before the

other cognitive measures.

Cognitive Measures

National Adult Reading Test (NART: Nelson, 1991). The participants

were given the NART to provide an estimate of the participants verbal IQ

performance.

Matching to Sample Visual Search task. CANTAB (Cambridge Cognition

Ltd). This sub test of the CANTAB is a speed/accuracy trade off task that

tests the subjects ability to match visual samples and measures their choice

and movement time. The sample stimulus appears in the center of the screen

and is an abstract pattern composed of 4 colored elements. After a brief delay

1, 2, 4, or 8 similar patterns appear around the edge of the screen. The

incorrect patterns are composed of juggled elements of the sample pattern

and only one of them matches the one in the center of the screen. The subject

must hold down a press pad to obtain the sample pattern and the matching

stimuli. When a choice has been made the subject releases the pad and

identifies the matching pattern by touching it. The matching to sample visual

search task resembles the Matching Familiar Figures test first developed by

Kagan (1965) who used it to measure reflection the amount of time spent

thinking about a response before making a decision, later developed further

by Cairns and Cammock (1978); it has been used to measure impulsivity

taking into account both time of response and number of errors made

(Messer and Brodzinsky, 1981). The Matching to Sample Visual Search task

gives two reaction time measures, choice time on the basis of the release of

the press pad, and movement time from the release of the pad to the touch

of the screen. Errors are also recorded. Results are given only for the 4 and

8-pattern condition (conditions 1 and 2 are very easy and performance runs

at ceiling with young adults).

Spatial Working Memory. CANTAB (Cambridge Cognition Ltd). This

subtest of CANTAB is a self ordered search task that requires participants

to search through a spatial array of boxes to collect tokens hidden inside.

At any one time there will be one single token hidden. The key instruction

is that once a blue token has been found inside a box, then that box will

never be used again to hide a token. There are trials of 3, 4, 6, and 8 boxes.

There are two types of errors in this task, within- and between-search

errors. A between-search error occurs when a participant returns to a

box in which a token has previously been found and a within search

error occurs when a participant returns to a box within the same search.

Results refer to between-search errors and are given only for the 6 and

8 boxes condition as in the 3 and 4 box conditions error rates are very low.

A further variable was the strategy score, which indicates the particular

sequence that participants follow in each session. A high score indicates

320

TOWNSHEND AND DUKA

poor strategy. The two CANTAB tasks were presented in counter balanced order.

The Vigilance Task for Adults from the Gordon Diagnostic System (Gordon et al., 1986). In this task participants are required to press a button on

a purpose-built electronic machine, which briefly displays 3 digits in fast,

random succession on a 3 column, LED display. Participants are required

to concentrate only on the digit in the middle column of the display, and

are instructed to press the blue button every time a 1 is followed by 9

(1 being the alerting stimulus and 9 being the target stimulus). The task

measures the subjects ability to inhibit responding under conditions that

make demands for sustained attention and impulse control. The main

variable in this task is errors of commission. Errors of commission are

targetrelated errors recorded when a response is made to the target

stimulus 9 or to the alerting stimulus 1 when they are not in the

sequence 1 / 9/.

Target Variables

For the purpose of this paper, the target variables are the reaction time,

movement time and number of errors made in the Matching to Sample

Visual Search task; the between search errors and strategy score in the

Spatial Working Memory task; errors of commission in the Vigilance task

for adults from the Gordon Diagnostic System; self-reported current

mood, alcohol expectancies and personality. All other measures represent

correlates.

Statistical Methods

For the cognitive tasks and the POMS composite factors arousal and

positive mood, initial analyses were performed using Univariate analysis

or mixed ANOVAs (task condition was the within factor) with group (2

levels: binge drinkers and nonbinge drinkers) and gender (2 levels) as the

between subject factors. For the Alcohol Expectancy and the TCI questionnaire ratings Multivariate analyses were performed with the factors

from the questionnaires as the dependent variables and with group (2

levels: binge drinkers and nonbinge drinkers) and gender (2 levels) as

fixed factors. Where an interaction was found between binge drinking

group and gender, further analysis was performed on males and females

separately. Where there was no interaction gender was not explored

further, as binge drinking was the behavior of interest in this study.

Independent t-tests were performed to analyze differences in demographic characteristics between nonbinge and binge drinkers and between

males and females within binge or nonbinge drinkers group. Between

group differences (units per week, age of starting to drink and drug use

score) were entered as covariates where binge drinkers performed differ-

ently on cognitive tasks. All procedures were carried out using SPSS

software version 11.5.

RESULTS

Group Demographics

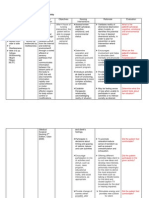

Table 1 shows the demographic data for the drinking

pattern groups and for males and females within the

groups. There are an unequal number of males and females

in the binge drinking and nonbinge drinking groups, which

may reflect real world population ratios. Alcohol units and

age of starting drinking were different between the groups

with the binge drinkers drinking more alcohol units per

week [t(70) 3.5; p 0.01) and starting earlier regular

drinking [t(70) 2.84; p 0.05]. There was also a difference between bingers and nonbingers with respect to drug

use score with binge drinkers having higher drug use score

than nonbinge drinkers [t(70) 2.358; p 0.021). There

were no differences between males and females for any of

the demographic characteristics in the nonbinge drinker

group [ts(32) 1.8]. Only a marginal difference between

males and females in the binge group was found with males

consuming more units per week [t(36) 2.01; p 0.052].

SIQ

There were 22 nonbinge drinkers and 24 binge drinkers

who had siblings over the age of 16 years. There were

differences between groups [t(44) 2.1; p 0.05) in the

amount of reported alcohol use by their nearest aged siblings [(mean SD), nonbinge drinkers: 11.7 10.0; binge

drinkers: 19.5 13.9] but not in drug use or in family

history of alcoholism (data not shown). A Pearson correlation using the population with siblings (n 60) from the

total pool (n 97) found that the amount of sibling alcohol

Table 1. Demographic Data for Non-Binge and Binge Drinkers and for Males and Females

Non-binge drinkers

Group characteristics

Number

Age

Alcohol units per weeka

Binge drinking score

Estimated IQ (NART)

Age of starting drinking

Drug use score

Cigarette smokers (n)

Occasional use of cannabis (n)

Regular use of cannabis (n)

XTC and/or other drug use (n)

Data are presented as mean (SD).

a

One unit is 8 g of alcohol.

b

p 0.005 compared to binge drinkers.

c

p 0.05.

Binge drinkers

Total

Males

Females

Total

Males

Females

34

20.9

(2.5)

20.5

(11.9)b

10.6

(3.4)b

107.9

(7.9)

15.3

(1.6)c

0.94

(1.04)c

10

13

2

5

13

20.4

(1.9)

22.2

(11.7)

11.2

(2.8)

108.5

(7.2)

16.0

(1.9)

0.62

(0.87)

4

5

0

1

21

21.2

(2.8)

18.7

(12.1)

10.3

(3.8)

107.6

(8.4)

14.9

(1.3)

1.14

(1.1)

6

8

2

4

38

20.9

(2.6)

33.3

(19.0)

40.4

(16.1)

107.6

(5.7)

14.4

(1.3)

1.53

(1.06)

11

13

9

9

23

20.9

(2.9)

38.2

(21.3)

37.1

(13.8)

108.6

(5.1)

14.8

(1.3)

1.48

(1.17)

5

6

5

6

15

21.1

(2.1)

26.0

(11.9)

45.5

(18.4)

106.1

(6.4)

14.0

(1.4)

1.60

(0.91)

6

7

4

3

321

BINGE DRINKING, MOOD AND COGNITION

Table 3. Profile of Mood States, Arousal and Positive Mood Composite Score

in the Non-Binge and Binge Drinkers

POMS factors

Non-binge drinkers (n 34)

Arousal

0.05 (1.53); range 2.402.69

Positive Mooda

1.00 (0.81); range 0.632.33

Binge drinkers (n 38)

0.55 (1.53); range 3.012.34

0.54 (1.17); range 2.472.33

Mean (SEM).

a

p 0.045 (univariate analysis of variance, group effect).

were found. There was no relationship between current

positive mood and time of last drink indicating that their

low current mood was not due to withdrawal from alcohol

in the binge drinkers.

Fig. 1. The relationship between binge drinking score of all participants with

nearest age siblings (over 16 years old) and estimated quantity of sibling alcohol

consumption.

Table 2. Scores on the Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire and the TCI for

Non-Binge Drinkers and Binge Drinkers, Mean (SEM)

Non-binge drinkers

(n 34)

Alcohol expectancy factors

Sociability

Tension reduction

Liquid courage

Sexuality

Cognitive and behavioral

impairment

Risk and aggression

Negative self perception

TCI factors

Novelty seeking

Harm avoidance

Reward dependence

Persistence

Self directedness

Co-cooperativeness

Self-transcendence

26.1

7.4

12.5

9.7

23.7

(.52); range 2031

(.25); range 410

(.38); range 917

(.34); range 514

(.87); range 1436

Binge drinkers

(n 38)

26.6 (.56); range 1832

7.5 (.28); range 411

13.1 (.38); range 818

9.9 (.39); range 514

24.7 (.56); range 1731

12.0 (.50); range 719

7.2 (.43); range 415

12.8 (.43); range 618

7.9 (.40); range 415

21.5 (1.03); range 834

15.7 (1.23); range 530

16.6 (.67); range 924

5.26 (.35); range 18

26.6 (1.36); range 740

33.0 (1.16); range 941

15.5 (1.22); range 030

24.0 (1.07); range 935

14.3 (1.44); range 130

15.6 (.66); range 822

4.5 (.38); range 18

24.2 (1.47); range 540

31.0 (1.18); range 1341

13.6 (1.06); range 529

use was most closely related to the participants binge

drinking score (Fig. 1; Pearson R 0.358, p 0.01). A

Pearson correlation using only the population with siblings

among the binge drinkers and nonbinge drinkers group (n

46) found also that the amount of sibling alcohol use was

most closely related to the participants binge drinking

score (Pearson R 0.422; p 0.01).

Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire and TCI

The 7 factor ratings from the Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire and from the TCI are presented in table 2. Multivariate analysis on the 7 factors of each questionnaire

separately and with the fixed factors group and gender

found no significant interactions or main effects (F7,62

2.0).

Profile of Mood States

Table 3 shows means and SEM of arousal and positive mood scores in binge and nonbinge drinkers. Univariate analysis for positive mood found a significant group

effect (F1,71 4.2; p 0.045) with binge drinkers being

lower on positive mood. No other effects or interactions

Cognitive Measures

CANTAB; Matching to Sample Visual Search. Due to

technical reasons values from 3 participants in the nonbinge drinkers and 4 participants in the binge drinkers

group were missing. A mixed ANOVA on choice time (4

and 8 pattern choice) in the MTS task found no effect of

gender but a group (2 levels; binge drinkers and nonbinge

drinkers) pattern (2 levels: 4 and 8 pattern condition)

interaction (F1, 61 4.4, p 0.05). Further investigation

showed that the binge drinkers were faster in their choice

time in the 8 pattern, but not in the 4-pattern condition

(Fig. 2a). Mixed ANOVA on movement time (4 and 8

pattern condition) revealed a main effect of group (F1,61

5.3; p 0.05) with binge drinkers being overall faster in

movement time than nonbinge drinkers (Fig. 2b). There

were no differences in the number of errors made. None of

the covariates entered (units per week, age of starting to

drink and drug use score) affected the group results.

CANTAB; Spatial Working Memory. Due to technical

reasons values from 2 participants in the nonbinge drinkers

group were missing. A mixed ANOVA on between trial

errors (6 and 8 boxes condition) found a gender by binge

drinking group interaction (F1,66 10.26; p 0.005).

Consequently the population was split by gender and males

and females examined separately. A further mixed

ANOVA on errors for males and females separately, found

a group effect (F1,32 6.3; p 0.05) only in females

indicating that female binge drinkers (n 15) made more

errors than female nonbinge drinkers (n 19; Fig. 3). A

Univariate analysis on strategy scores showed no interactions or main effects. None of the covariates entered (units

per week, age of starting to drink and drug use score)

affected the group results.

Gordon Diagnostic System; Vigilance task for adults. Due

to technical reasons values from 2 participants in the nonbinge drinkers and 1 subject in the binge drinkers group

were missing. A Univariate Analysis with errors of commission as the dependent variable found a group by gender

interaction (F1, 68 5.3; p 0.05) so the population was

split by gender for further analysis. A further Univariate

Analysis on errors of commission for males and females

separately, found a group effect (F 1,33 4.6; p 0.05)

only in females indicating that female binge drinkers (n

322

TOWNSHEND AND DUKA

Fig. 2. Choice time (a) and movement time (b) for the 4- and 8-pattern condition (ms; mean SEM) in the CANTAB Matching to Sample Visual Search task for binge

and nonbinge drinkers. *p 0.05 compared to nonbinge drinkers.

15) made more errors than female nonbinge drinkers (n

19; Fig. 4). When age of starting drinking was entered as a

covariate the group difference became marginal (F 1,33

4.0; p 0.06). No effect of the other covariates (units per

week and drug use score) was found.

DISCUSSION

The present study set out to examine the validity of a new

method of identifying binge drinking in young, healthy

social drinkers, and to look at differences in cognitive

performance and mood between groups with different

drinking patterns. Using a questionnaire method that asks

about drinking behavior rather then quantity of alcohol

consumed, we have been able to show differences in cog-

nitive performance between groups of young healthy adults

who are similar in aspects other than their drinking behavior. However it should be noted that there is an important

limitation to the study as the differentiation of binge drinkers and nonbinge drinkers was based on information provided by the participants themselves rather than objective

measures, although we have previously found that information about drinking behavior collected from the AUQ and

drinking behavior recorded daily in a diary were very

closely related (Townshend and Duka, 2002).

The groups were well matched for age and IQ but the

binge drinkers started drinking earlier than the nonbinge

drinkers. They also consumed more alcohol and used more

drugs than the nonbinge drinkers, and drug use and binge

drinking scores were positively related in the whole popu-

Fig. 3. Between search errors (total errors 6 and 8 boxes, mean SEM)

in the CANTAB Spatial Working Memory task, for male and female binge

and nonbinge drinkers. *p 0.05 compared to female nonbinge drinkers

and male binge drinkers.

BINGE DRINKING, MOOD AND COGNITION

323

Fig. 4. Errors of commission in the Gordon Diagnostic System Vigilance

task for male and female binge and nonbinge drinkers; *p 0.05 compared

to female nonbinge drinkers and male binge drinkers.

lation (data not shown). The concurrent use of alcohol and

drugs has been previously reported in several studies [e.g.,

(Sutherland and Willner, 1998)] and has been suggested to

be due to one of two hypotheses, either to alcohol acting as

a gateway to illicit drugs (Kandel et al., 1992), or as part of

a general behavior pattern in which alcohol use has a lower

threshold to other drugs and is easier to obtain (Jessor,

1987). The results from this current study do not distinguish

between these two hypotheses but provide further evidence

of a relationship between increased frequency of drug use

and increased frequency of drunkenness.

Although neither the units of alcohol drunk per week nor

the higher incidence of drug use found in binge drinkers

compared to nonbinge drinkers was found to relate to the

impairments seen in performance on cognitive tasks among

binge drinkers, a contribution of these factors cannot be

excluded from the present data.

Participants were asked to estimate the alcohol and drug

use of their siblings. The alcohol use of the nearest aged

sibling was strongly related to the participants binge drinking score. Peer influence would appear to have a strong

impact on drinking behavior and a similar result has previously been shown in a smoking study in which sibling

smoking was the one of the strongest predictors of smoking

behavior (Wilkinson and Abraham, 2004). However it cannot be ruled out that similarities between sibling drinking in

this current study may simply be due to biased reporting by

the participants [see Weitzman et al. (2003) for similar data

on peers] Conversely, family history of alcohol use was not

related to binge drinking behavior or to sibling alcohol use,

although only about 40% of participants had any family

members with alcohol dependency problems, the majority

of whom were second degree relatives. Although these data

suggest that binge drinking in the population of social

drinkers in the present study was less the result of a genetic

predisposition and more of a cultural influence or peer

pressure, future studies are needed to examine a possible

genetic predisposition of binge drinking by using more

robust measures of family history of alcoholism than self

reports as we used in the present study.

Current mood states in the binge drinkers group were less

positive than their nonbinge drinking counterparts and this

was not related to alcohol withdrawal as measured by time of

last drink. Increased anxiety and negative emotional sensitivity

has been reported previously in alcohol dependent participants with multiple alcohol withdrawals (Adinoff et al., 1994;

Duka et al., 2002). Although alcohol abuse is often comorbid

with low mood states, whether it is a cause or effect relationship is not clear. Increased anxiety could advance the progression to alcohol dependence particularly when coupled to a

binge drinking induced loss of executive protective inhibitory

functions.

The finding of faster reaction times on the Matching to

Sample Visual Search task in the binge drinkers group is of

interest. Such a finding suggests that binge drinkers require

less time to reflect and make their choice, although choice

time was found to be faster only in the 8, whereas movement time both in the 6 and 8 pattern condition. Such an

increase in the speed of response may suggest that binge

drinkers are more efficient in response execution with regard to a visuospatial task. As the task was quite easy and

there were very few errors made overall, we cannot suggest

that binge drinkers, as predicted, might be more impulsive;

further studies are required to address this question.

The Vigilance task from the Gordon Diagnostic System

is similar to a go / no go paradigm, in which participants

have to inhibit their responding following the alerting stimulus, until the target stimulus appears. The task measures

both sustained attention and impulse control and the female binge drinkers were particularly impaired in this task

being unable to inhibit their response to the alerting stimulus suggesting a lack of inhibitory control from the frontal

lobes. Interestingly when age of starting drinking was entered as a covariate the significant impairment found in the

females became marginal indicating the importance of

starting drinking early as a contributing factor to these

effects of binge drinking. Previous studies have also shown

impairments in cognitive function associated with heavy

drinking during early adolescence (Brown et al., 2000). We

found also group differences in females in the Spatial

Working Memory task in which the binge-drinking females

made more errors than their nonbinge-drinking counterparts. No other factor was found to contribute to this effect.

We have also previously shown that binge drinkers made

more between search errors in the Spatial Working Memory task compared to nonbinge drinkers (Weissenborn and

Duka, 2003), however, there was not gender difference

found. One reason for this discrepancy could be that the

324

TOWNSHEND AND DUKA

female binge drinkers in the current study had a higher

binge score (45.5 4.7) than the female binge drinkers in

the previous study (28.0 2.6). Additionally in the previous

study participants were tested under alcohol or placebo and

the grouping of binge and nonbinge drinkers was based on

a posthoc median split. Further research on the relationship between gender and binge drinking is needed to clarify

the discrepancy between the two studies. Interestingly male

binge drinkers drank more alcohol than female binge

drinkers although their binge scores were lower. This finding might indicate that female drinkers, although they consume less, may become drunk more often when drinking,

giving them a higher binge score for the amount of alcohol

drunk compared to males. Thus it is perhaps not surprising

that female binge drinkers were more impaired than male

binge drinkers.

Previous studies examining drinking habits (Deckel et al.,

1995) or the adverse consequences of drinking (Giancola et

al., 1996) in young adult social drinkers, have shown a

relationship between impaired executive function and both

the frequency of drinking to get high and get drunk

(Deckel et al., 1995) or the severity of drinking consequences (Giancola et al., 1996). Although impairment in

certain cognitive tasks, also shown in the present study,

might be the cause of extreme drinking patterns (including

binge drinking) as the above studies indicate, data from

animals suggest that binge drinking can induce cortical

damage and lead to cognitive deficits like perseverative

responding in a spatial learning task (Obernier et al.,

2002b). It is acknowledged however that only a prospective

study looking at cognitive performance in adolescents before and after starting binge drinking would clarify these

questions.

In summary, these results suggest that a binge drinking

score can be used to show differences in cognition and

mood in nondependent healthy social drinkers. Patterns of

drinking may reveal differences that quantity of alcohol

consumed does not, and may be more analogous to the

effects of repeated detoxification seen in alcoholic patients.

In particular the results have revealed that binge drinking is

associated with impaired performance in cognitive tasks in

females more than males. The importance of the age of

starting drinking as a contributing factor to the findings

presented here has also been highlighted. These findings

furthermore indicate the possibility that low mood states

and loss of executive function due to binge drinking may

combine to contribute to the progression of dangerous

drinking levels and alcohol dependence.

REFERENCES

Adinoff B, ONeill K, Ballenger JC (1994) Alcohol withdrawal and limbic

kindling. Am J Addict 4:517.

Blume AW, Schmaling KB, Marlatt AG (2003) Predictors of change in

binge drinking over a 3-month period. Addict Behav 28:10071012.

Brown SA, Tapert SF, Granholm E, Delis DC (2000) Neurocognitive

functioning of adolescents: effects of protracted alcohol use. Alcohol

Clin Exp Res 24:164 171.

Cairns E, Cammock T (1978) Development of a more reliable version of

the Matching Familiar Figures Test. Dev Psychol 13:555560.

Cloninger CR, Przybeck TR, Svrakic DM, Wetzel RD (1994) The temperament and character inventory (TCI): a guide to its development

and use. Center for Psychobiology of Personality., Center for Psychobiology of Personality.

Crews FT, Braun CJ, Ali R, Knapp DJ (2001) Interaction of nutrition and

binge ethanol treatment on brain damage and withdrawal. J Biomed Sci

8:134 142.

Crews FT, Braun CJ, Hoplight B, Switzer RC, 3rd, Knapp DJ (2000)

Binge ethanol consumption causes differential brain damage in young

adolescent rats compared with adult rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24:

17121723.

De Bellis MD, Clark DB, Beers SR, Soloff PH, Boring AM, Hall J, Kersh

A, Keshavan MS (2000) Hippocampal volume in adolescent-onset alcohol use disorders. Am J Psychiatry 157:737744.

de Wit H, Doty P (1994) Preference for ethanol and diazepam in light and

moderate social drinkers: a within-subjects study. Psychopharmacology

(Berl) 115:529 538.

Deckel AW, Bauer L, Hesselbrock V (1995) Anterior brain dysfunctioning

as a risk factor in alcoholic behaviors. Addiction 90:13231334.

Duka T, Gentry J, Malcolm R, Ripley TL, Borlikova G, Stephens DN,

Veatch LM, Becker HC, Crews FT (2004) Consequences of multiple

withdrawals from alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28:233246.

Duka T, Townshend JM, Collier K, Stephens DN (2002) Kindling of

withdrawal: a study of craving and anxiety after multiple detoxifications

in alcoholic inpatients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 26:785795.

Duka T, Townshend JM, Collier K, Stephens DN (2003) Impairment in

cognitive functions after multiple detoxifications in alcoholic inpatients.

Alcohol Clin Exp Res 27:15631572.

Fromme K, Stroot, E., Kaplan, D. (1993) Comprehensive effects of Alcohol: development and psychometric assessment of a new expectancy

questionnaire. Psychological assessment 5:19 26.

Giancola PR, Zeichner A, Yarnell JE, Dickson KE (1996) Relation

between executive cognitive functioning and the adverse consequences

of alcohol use in social drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 20:1094 1098.

Gilligan SB, Reich T, Cloninger CR (1987) Etiologic heterogeneity in

alcoholism. Genet Epidemiol 4:395 414.

Gordon M, McClure F, Post E (1986) Interpretive guide to the Gordon

Diagnostic System. (DeWitt: Gordon Systems, Inc).

Hunt WA (1993) Are binge drinkers more at risk of developing brain

damage? Alcohol 10:559 561.

Jessor R (1987) Problem-behavior theory, psychosocial development, and

adolescent problem drinking. Br J Addict 82:331342.

Kagan J (1965) The Matching Familiar Figures Test. Harvard University

Press, Cambridge MA.

Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K, Chen K (1992) Stages of progression in drug

involvement from adolescence to adulthood: further evidence for the

gateway theory. J Stud Alcohol 53:447 457.

McNair Dm, Lorr M, Doppleman LF (1971) Profile of Mood States

(Manual). Education and Industrial Testing Service, Education and

Industrial Testing Service.

Mehrabian A, Russell JA (1978) A questionnaire measure of habitual

alcohol use. Psychol Rep 43:803 806.

Messer SB, Brodzinsky DM (1981) Three year stability of reflectionimpulsivity in young adolescents. Dev Psychol 17:848 850.

Moselhy HF, Georgiou G, Kahn A (2001) Frontal lobe changes in alcoholism: a review of the literature. Alcohol Alcohol 36:357368.

Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad A, Denny C, Serdula MK, Marks JS

(2003) Binge drinking among US adults. Jama 289:70 75.

Nelson HE, OConnell A (1978) Dementia: the estimation of premorbid

intelligence levels using the New Adult Reading Test. Cortex 14:234

244.

BINGE DRINKING, MOOD AND COGNITION

Obernier JA, Bouldin TW, Crews FT (2002a) Binge ethanol exposure in

adult rats causes necrotic cell death. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 26:547557.

Obernier JA, White AM, Swartzwelder HS, Crews FT (2002b) Cognitive

deficits and CNS damage after a 4-day binge ethanol exposure in rats.

Pharmacol Biochem Behav 72:521532.

Ripley TL, OShea M, Stephens DN (2003) Repeated withdrawal from

ethanol impairs acquisition but not expression of conditioned fear. Eur

J Neurosci 18:441 448.

Stephens DN (1995) A glutamatergic hypothesis of drug dependence: extrapolations from benzodiazepine receptor ligands. Behav Pharmacol 6:425446.

Stephens DN, Brown G, Duka T, Ripley TL (2001) Impaired fear conditioning but enhanced seizure sensitivity in rats given repeated experience of withdrawal from alcohol. Eur J Neurosci 14:20232031.

Sutherland I, Willner P (1998) Patterns of alcohol, cigarette and illicit

drug use in English adolescents. Addiction 93:1199 1208.

Townshend JM, Duka T (2002) Patterns of alcohol drinking in a population of young social drinkers: a comparison of questionnaire and diary

measures. Alcohol Alcohol 37:187192.

Townshend JM, Duka T (2003) Mixed emotions: alcoholics impairments

in the recognition of specific emotional facial expressions. Neuropsychologia 41:773782.

325

Veatch LM, Gonzalez LP (1999) Repeated ethanol withdrawal delays

development of focal seizures in hippocampal kindling. Alcohol Clin

Exp Res 23:11451150.

Wechsler H, Austin SB (1998) Binge drinking: the five/four measure.

J Stud Alcohol 59:122124.

Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Castillo S (1994)

Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college. A

national survey of students at 140 campuses. Jama 272:16721677.

Weissenborn R, Duka T (2003) Acute alcohol effects on cognitive function in social drinkers: their relationship to drinking habits. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 165:306 312.

Weitzman ER, Nelson TF, Wechsler H (2003) Taking up binge drinking

in college: the influences of person, social group, and environment.

J Adolesc Health 32:26 35.

White AM, Jamieson-Drake DW, Swartzwelder HS (2002) Prevalence

and correlates of alcohol-induced blackouts among college students:

results of an e-mail survey. J Am Coll Health 51: 117- 9:122131.

Wilkinson D, Abraham C (2004) Constructing an integrated model of the

antecedents of adolescent smoking. B J Health Psychol 9:315333.

You might also like

- Immature Frontal Lobe Contributions To Cognitive Control in Children - Evidence From FMRIDocument11 pagesImmature Frontal Lobe Contributions To Cognitive Control in Children - Evidence From FMRIFati NovNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Impulsivity Phenotypes Characterized by Distinct Brain NetworksDocument8 pagesAdolescent Impulsivity Phenotypes Characterized by Distinct Brain NetworksFati NovNo ratings yet

- Altered Impulse Control in Alcohol Dependence - Neural Measures of Stop Signal Performance.Document11 pagesAltered Impulse Control in Alcohol Dependence - Neural Measures of Stop Signal Performance.Fati NovNo ratings yet

- Maturation of Brain Function Associated With Response InhibitionDocument8 pagesMaturation of Brain Function Associated With Response InhibitionhandpamNo ratings yet

- Immature Frontal Lobe Contributions To Cognitive Control in Children - Evidence From FMRIDocument11 pagesImmature Frontal Lobe Contributions To Cognitive Control in Children - Evidence From FMRIFati NovNo ratings yet

- Stop-Signal Reaction-Time Task Performance - Role of Prefrontal Cortex and Subthalamic NucleusDocument11 pagesStop-Signal Reaction-Time Task Performance - Role of Prefrontal Cortex and Subthalamic NucleusFati NovNo ratings yet

- Cortical Gray Matter in Attention-Deficit-hyperactivity Disorder - A Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging StudyDocument12 pagesCortical Gray Matter in Attention-Deficit-hyperactivity Disorder - A Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging StudyFati NovNo ratings yet

- El Lenguaje y Los Trastornos Del NeurodesarrolloDocument7 pagesEl Lenguaje y Los Trastornos Del NeurodesarrolloDany MenaresNo ratings yet

- Alcoholismo y P3aDocument16 pagesAlcoholismo y P3aFati NovNo ratings yet

- An FMRI Study of Response Inhibition in Youths With A Family History of AlcoholismDocument4 pagesAn FMRI Study of Response Inhibition in Youths With A Family History of AlcoholismFati NovNo ratings yet

- BlazquezDocument10 pagesBlazquezFati NovNo ratings yet

- J Epidemiol Community HealthDocument10 pagesJ Epidemiol Community HealthFati NovNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0028393209001596 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S0028393209001596 MainFati NovNo ratings yet

- Alcohol Cues Increase Cognitive Impulsivity in Individuals With AlcoholismDocument8 pagesAlcohol Cues Increase Cognitive Impulsivity in Individuals With AlcoholismFati NovNo ratings yet

- J Epidemiol Community HealthDocument10 pagesJ Epidemiol Community HealthFati NovNo ratings yet

- 188Document10 pages188Fati NovNo ratings yet

- Lopez HernandezDocument6 pagesLopez HernandezFati NovNo ratings yet

- 5Document11 pages5Fati NovNo ratings yet

- Binge DinkingDocument36 pagesBinge DinkingFati NovNo ratings yet

- TDAH, Trastorno Por Déficit de Atención Con Hiperactividad en Adultos: Caracterización Clínica y TerapéuticaDocument7 pagesTDAH, Trastorno Por Déficit de Atención Con Hiperactividad en Adultos: Caracterización Clínica y Terapéuticainfo-TEA50% (2)

- Binge DinkingDocument36 pagesBinge DinkingFati NovNo ratings yet

- A Do Les C Deficit AtencDocument11 pagesA Do Les C Deficit AtencRaul Hernandez HernandezNo ratings yet

- Tops and Boksem, 2011Document14 pagesTops and Boksem, 2011Fati NovNo ratings yet

- Missoner, Et Al 2006Document10 pagesMissoner, Et Al 2006Fati NovNo ratings yet

- Ffee en TB Pediátrico y Comorbilidad Con TdahDocument18 pagesFfee en TB Pediátrico y Comorbilidad Con TdahFati NovNo ratings yet

- Emocion Negativa Deteriora MT en Pacientes Pedáitrcos Con TB Tipo 1Document17 pagesEmocion Negativa Deteriora MT en Pacientes Pedáitrcos Con TB Tipo 1Fati NovNo ratings yet

- Funcionamiento Neuropsicológico en Jóvenes Con TBDocument7 pagesFuncionamiento Neuropsicológico en Jóvenes Con TBFati NovNo ratings yet

- Levy and Wagner, 2011Document23 pagesLevy and Wagner, 2011Fati NovNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow: Mark KellandDocument37 pagesCarl Rogers and Abraham Maslow: Mark KellandJohn paulNo ratings yet

- Thesis Proposal AssumptionsDocument6 pagesThesis Proposal Assumptionsafbtbegxe100% (1)

- Depression Worksheet - 02 - Behavioural Activation PDFDocument1 pageDepression Worksheet - 02 - Behavioural Activation PDFsolNo ratings yet

- Amelia Djajadi 717191033Document12 pagesAmelia Djajadi 717191033Amelia DjajadiNo ratings yet

- Classwork 5 Properties of Human LanguageDocument3 pagesClasswork 5 Properties of Human LanguageViviana Zambrano100% (1)

- EFT Premarital Curriculum - JordanDocument33 pagesEFT Premarital Curriculum - JordanojmalleryNo ratings yet

- Dementia Toolkit PDFDocument92 pagesDementia Toolkit PDFDana Socolov100% (1)

- Reflection of Psychology 1010Document2 pagesReflection of Psychology 1010api-270635734No ratings yet

- Deficient Diversional ActivityDocument2 pagesDeficient Diversional ActivityKimsha Concepcion100% (2)

- Inquiry 1 - How Do We LearnDocument19 pagesInquiry 1 - How Do We Learnapi-504254249No ratings yet

- O Level Biology NotesDocument9 pagesO Level Biology NotesIra100% (1)

- Practice Test - Error IdentificationDocument5 pagesPractice Test - Error IdentificationTùng Lâm TrầnNo ratings yet

- Agapay: Wellness and Productivity For The Elderly Against DespairDocument9 pagesAgapay: Wellness and Productivity For The Elderly Against DespairJoy ZamudioNo ratings yet

- Pepsi Screening Case StudyDocument11 pagesPepsi Screening Case Studyapi-459442670No ratings yet

- Environmental Enrichment and Neuronal Plasticity - Oxford HandbooksDocument42 pagesEnvironmental Enrichment and Neuronal Plasticity - Oxford HandbooksAdela Fontana Di TreviNo ratings yet

- TuriyaDocument10 pagesTuriyaMircea CrivoiNo ratings yet

- Guided Meditation - Tara Brach - AttachmentDocument1 pageGuided Meditation - Tara Brach - AttachmentSantiago Carey100% (1)

- Sensory PhysiologyDocument7 pagesSensory PhysiologyStd DlshsiNo ratings yet

- Animal PerceptionDocument11 pagesAnimal PerceptionDanaGrujićNo ratings yet

- Promoting Work Life Balance Among Higher Learning Institution Employees: Does Emotional Intelligence Matter?Document8 pagesPromoting Work Life Balance Among Higher Learning Institution Employees: Does Emotional Intelligence Matter?Global Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Alcohol Use DisorderDocument28 pagesAlcohol Use DisorderAkhilesh Parab0% (2)

- Facilitating Meaningful Learning ExperiencesDocument3 pagesFacilitating Meaningful Learning ExperiencesNur SholihahNo ratings yet

- REading and Writing Whole Numbers Up To 10, 000Document2 pagesREading and Writing Whole Numbers Up To 10, 000danica ragutanaNo ratings yet

- Motor Unit Number Index (Munix) - Principle, Method, and Findings in Healthy Subjects and in Patients With Motor Neuron Disease PDFDocument10 pagesMotor Unit Number Index (Munix) - Principle, Method, and Findings in Healthy Subjects and in Patients With Motor Neuron Disease PDFMauricio ZambrottaNo ratings yet

- KMY4013 LU4 Sensory PerceptionDocument31 pagesKMY4013 LU4 Sensory PerceptionimanNo ratings yet

- Aptitude in SLA PDFDocument5 pagesAptitude in SLA PDFVitaManieztNo ratings yet

- APA - DSM5 - Severity of Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms Adult PDFDocument3 pagesAPA - DSM5 - Severity of Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms Adult PDFStephanny Per EspitiaNo ratings yet

- Observable Behaviour in Making Sound DecisionsDocument22 pagesObservable Behaviour in Making Sound DecisionsRafi Muhammad RaoNo ratings yet

- Blume Et Al., 2019 - Effects of Light On Human Circadian Rhythms, Sleep and MoodDocument10 pagesBlume Et Al., 2019 - Effects of Light On Human Circadian Rhythms, Sleep and MoodSAMARAH SANTOSNo ratings yet

- The Pomodoro TechniqueDocument14 pagesThe Pomodoro TechniquesmartguidesNo ratings yet