Professional Documents

Culture Documents

RR Everett Reinhardt

Uploaded by

Chunka OmarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

RR Everett Reinhardt

Uploaded by

Chunka OmarCopyright:

Available Formats

Resource Reprints from the

International Trumpet Guild

to promote communications among trumpet players around the world and to improve the artistic level

of performance, teaching, and literature associated with the trumpet

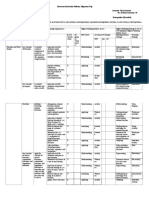

Thomas G. Everett An Interview with Dr. Donald S. Reinhardt.

Originally published in The Brass World (1974. Vol. 2, No. 4.

pp. 93-97)

The International Trumpet Guild (ITG) is the copyright owner of all data contained in

this file. ITG gives the individual end-user the right to:

Download and retain an electronic copy of this file on a single workstation that you

own

Transmit an unaltered copy of this file to any single individual end-user, so long as

no fee, whether direct or indirect is charged

Print a single copy of pages of this file

Quote fair use passages of this file in not-for-profit research papers as long is the

ITGJ, date, and page number are cited as the source.

The International Trumpet Guild, prohibits the following without prior written

permission:

Duplication or distribution of this file, the data contained herein, or printed copies

made from this file for profit or for a charge, whether direct or indirect

Transmission of this file or the data contained herein to more than one individual

end-user

Distribution of this file or the data contained herein in any form to more than one

end user (as in the form of a chain letter)

Printing or distribution of more than a single copy of pages of this file

Alteration of this file or the data contained herein

Placement of this file on any web site, server, or any other database or device that

allows for the accessing or copying of this file or the data contained herein by any

third party, including such a device intended to be used wholely within an institution.

For membership or other information, please contact:

David Jones, Treasurer

International Trumpet Guild

241 East Main Street #247

Westfield, MA 01086-1633 USA

Fax: 413-568-1913

Treasurer@trumpetguild.org

www.trumpetguild.org

Please retain this cover sheet with printed document.

Updated and reprinted by the International Trumpet Guild from an article in The Brass World, November 2, 1974, pp. 93-97.

An Interview with Dr. Donald S. Reinhardt

BY THOMAS EVERETT

When I received a review copy of the new augThe following interview consists of frequently asked

mented version of Encyclopedia of the Pivot System

questions about Reinhardts teachings. The interview

by Dr. Donald Reinhardt, I immediately thought of

took place April 4, 1972, at Reinhardts studio at

the confusion and misconceptions associated with this

1720 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

man and his teaching concepts. I, too, had much

misinformation and was skeptical about his so-called

T.E.: Why did you write the Encyclopedia of the

pivot system until 1972, when I decided to take a

Pivot System?

lesson with him to learn more about his teaching

D.R.: In June of 1939, after ten years of playing at

concepts. I dont believe the new text is as valuable as

the Fox Theatre, the musicians were released due to

personal contact with Reinhardt,

a change in policy. As they paid us

but it does present his teaching beoff in a lump sum, my wife and I

liefs, and discusses the function of

decided to take a vacation to the

the body in brass playing.

West Coast. (Gas was 13 a gallon

The first lesson is called an Orithen and we could get a good

entation and Analysis session and

chicken dinner for 35.)

lasts between three and four hours.

While stopping for lunch one day

It consists of discussions with

in Kansas, I heard some trombone

Reinhardt, listening and taking

sounds coming from the apartment

notes from prepared tapes, and a

above the road restaurant where

personalized session consisting of

we were dining. It turned out to be

analysis of playing faults and the

a poor thirteen-year-old boy, playproper methods for correcting these

ing a $39.95 Sears and Roebuck

faults. A discussion of the

Marceau trombone. He sounded

individuals jaw type pivot is interrible and was doing everything

cluded, along with exercise matewrong. In a few minutes, I showed

rial adapted for the individuals

him how to hold the horn, buzz his

particular needs. The tongue,

lips, and read from the left side of

breathing, and coordination are left

stand, and how to slur B-flat to D

Donald S. Reinhardt

for later lessons. Reinhardt is no

(which he couldnt do). He was

miracle worker, but he did make me aware of several

amazed at the progress he made in the short 20-25

faults I had, and he showed me ways of making

minute period. He asked how he could learn more of

better use of my natural facilities and physical atthese things, as he couldnt afford lessons, so I wrote

tributes. Not only did my sound open up and my

out some instructions for him.

playing improve, but also I became a bit more openI still remember the last question the boy asked as

minded and a better brass teacher.

he enthusiastically thanked me: Isnt there a book I

Donald S. Reinhardt, an alumnus of the Curtis

can buy somewhere with information in it that would

Institute of Music and holder of a Doctorate from

allow a fellow like me to teach myself to some extent?

Combs College of Music, has made a teaching career

As we continued traveling west, I thought of the

of brass specialization through his rare gift of pedaboy, and kept writing down material for him in a

gogy, analytic talent, and ability of expression through

three-ring notebook I kept on the drivers seat. When

the written and spoken word. He has several study

I returned home, I retyped it and elaborated on the

books published including the Concone Studies and

points I had made while writing in the car.

Pivot System Manual and is one of the most sought

I had been frustrated with eighteen teachers who

after and respected brass authorities in the country.

did not know how to teach. Not a single one of them

Reprinted by permission of Robert D. Weast, owner of The Brass World and Thomas G. Everett. New material 2000 International Trumpet Guild.

All photos courtesy of Streitwieser Foundation, Instrumentenmuseum, Schlo Kremsegg in Kremsmnster, Upper Austria

1974 Robert D. Weast. Revised version 2000 International Trumpet Guild.

Everett Reinhardt Interview 1

ever explained how to approach playing problems in

a physical sense. When I asked questions regarding

my many problems, one so-called authority said,

speak when spoken to! The experiences I had with

previous teachers, and that boy in Kansas, were my

reasons for putting years of dealing with brass problems and players on paper.

T.E.: Why do you call your Augmented Encyclopedia of the Pivot System a scientific text?

D.R.: Because the word scientific means to be

systematic and exact. My Pivot System is a scientific,

practical, proven method of producing the utmost in

range, power, endurance, and flexibility on the trumpet, trombone, and all other cupped-mouthpiece brass

instruments. I originated, organized, and perfected it

in over fifty years of research and experimentation

with many thousands of professional performers, supervisors, teachers, and students from all parts of

the world.

The Pivot System, working on tried and tested

principles, first analyzes and diagnoses the physical

equipment of the performer. It then presents a specific, concrete set of rules and procedures which enable the individual to utilize, with the greatest possible efficiency, the lips, teeth, jaw, and general

anatomy with which he is naturally endowed.

The Pivot System, in its entirety, shows the player

how effectively to transfer the purely mechanical command of his instrument into musical expression based

upon the most exacting modern conception and standards. It represents a thoroughly organized plan for

the development of the brass performer as a complete

musician. It coordinates tone production and technique with music theory, reading, phrasing, transposition, etc., in order to achieve as quickly as possible

for each individual his desired goal, whether it is in

the classical or jazz idioms. My division of physical

types into nine separate categories, and having them

visually proven with a transparent, plastic mouthpiece into downstream and upstream classifications;

my explanation and proof of the airstream spiral as it

passes through the cup, shoulder, throat, and backbore

of the mouthpiece and into the leadpipe of the instrument; my detailed categorization of eight different

physical tongue types and the proper way of manipulating each type; my lengthy and detailed discussion

of correct and incorrect breathing methods, etc., are

all positively scientific because the Augmented Encyclopedia of the Pivot System is a systematic and

exact presentation.

T.E.: How did your teaching philosophies become

associated with the Pivot System?

D.R.: When I was in my early teens, I wanted to

become a professional golfer. I was a caddy and had

won many caddy tournaments. I often played in the

Reinhardt with his trombone at age 18

low seventies, however, I soon learned that this was

to become my avocation, rather than my vocation. I

respected golf because, whenever a correct, scientific

approach was used, I could relate it in the same way

to my brass instrument studies and experiments.

The term Pivot System came from the golf links,

rather than from any of my brass inclinations. Initially, I was going to use my own name for my professional playing, teaching and writing, and use the

term Pivot System on the mouthpieces and accessories for brass instruments which I had intended to

manufacture. At that time all of this seemed very

logical; however, I soon found that my name and the

term Pivot System had become strongly entwined, at

least as far as the public was concerned. In short, I

went right along with the idea, not realizing how

many colleges and conservatories object to the word

system. In my Pivot System, every person is analyzed and treated as a separate mental and physical

entity; therefore, under my Pivot System banner there

are as many systems as there are people. In short,

1974 Robert D. Weast. Revised version 2000 International Trumpet Guild.

Everett Reinhardt Interview 2

the size-ten foot is not given a size-nine or -eleven

shoe. Oddly enough, these edifices of higher learning

do not object to the term Boehm system in relation to

flute and clarinet terminology, or military or conservatory systems for oboe, etc. Now, even if I did so

desire, it is a little too late in life to segregate my

name from the well-known colloquialism, Pivot System. I wish I could make colleges, conservatories,

and the brass profession comprehend this fact.

My Pivot System is based upon logic and common

sense, not a bunch of illogical tradition. Particularly

in the early days, this logical approach to playing a

cupped-mouthpiece brass instrument brought storms

of protest from many, simply because I refused to join

hands with illogical, traditional teaching approaches.

The informed consider talent the one attribute which

covers all. They fail to realize that progress is the

beginning of finding answers. Eventually, they must

forsake their crusade against logic and accept my

Pivot System. In the meantime, we must forgive

them for they know not what they do. They must

realize that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.

It must be remembered that I do not possess the

luxury of picking my own students: they must pick

me. I might add that the older I get, the more I see I

do not know too bad they have not arrived at this

realization.

T.E.: Do you feel that the Pivot System trains and

prepares a student for a particular style of music,

maybe more for the dance band than the symphonic

idiom?

D.R.: In addition to the theoretical musical work I

did during my eight years of conservatory and college

training, I studied harmony, counterpoint, composition, and arranging with six other teaching names

in the theoretical category. Then I became exposed to

the logic of the mathematical approach to writing.

My friends all warned me that this form of study

would stifle and stereotype any writing accomplishments I had made up to that point. Believe me, I

received no encouragement from anyone. However,

this study did not dwarf talent, but rather served as

an intelligent and logical augmentation to what I had

already accomplished. In fact, it served to expand my

thinking so that I could accept this new, fresh and

never-ending source of musical ideas and concepts.

Why will some in our musical field nearly always

condemn what they themselves are unable to comprehend?

The man teaching this mathematical approach to

writing was nothing short of a genius, both as a

mental giant and as a superb instructor, and I was

fortunate enough to study with him for several years

before his death. Certainly, what I learned from him

could be directed toward the symphonic or dance

Donald S. Reinhardt, Atlantic City, New Jersey, 1933

fields of writing, for it was applicable to any style or

musical situation. I am positive that his teachings

were not intended to lean one way or the other. Many

of todays fine Hollywood studio writers were students of this master teacher.

This may serve as an analogy for my Pivot System

approach, for it is intended to free the student of both

mental and physical playing obstacles that preclude

success. After the student has mastered my Pivot

System, it may be applied to the field of music of his

choice. It, too, does not lean one way or the other. I

have, and have had, students from all parts of the

world studying my Pivot System. Some are in the

commercial performance field, others are symphonic

players, and still others use it in their own teaching.

T.E.: Do you feel that your teaching techniques in

the Pivot System are in conflict with, or support

other generally accepted brass authorities?

D.R.: Regardless of whose names are mentioned

as accepted brass authorities, if the following logical and proven brass facts, which I have demonstrated to the brass community for over fifty years,

are not accepted or utilized simply because the

instructors sense of logic has been impaired or completely stymied by nonsensical, illogical, traditional

approaches and techniques for overall brass instruction, then my Pivot System definitely collides with

1974 Robert D. Weast. Revised version 2000 International Trumpet Guild.

Everett Reinhardt Interview 3

Doc Reinhardt enjoying a cigar amid the controlled clutter of his Chestnut Street studio

their mode of thinking in this regard. My Pivot System is based upon logic and common sense, and it

never bows to tradition when tradition becomes illogical. A few of the basic facts expressed by my Pivot

System are as follows:

1. We are all different both mentally and physically;

therefore, every brass student must be treated and

taught as a separate entity.

2. Smiling to ascend (pulling the mouth corners in

a backward manner so that the lips are stretched

across the teeth) was wrong, is wrong, and always

will be wrong. This old-time brass playing fallacy

is the most destructive of all teaching and playing concepts.

3. Spitting seeds, threads or confetti from the tip

of the tongue so that the tip of the tongue may

penetrate between the teeth and lips in order to

produce a clean, crisp attack is another destructive playing mannerism. Both the smiling to ascend and the spitting of seeds, threads, or con-

4.

5.

6.

7.

9.

1974 Robert D. Weast. Revised version 2000 International Trumpet Guild.

fetti to attack concepts have produced more brass

playing failures than all other incorrect teaching

points combined. They should have died at

Custers Last Stand.

Delaying the attack by bottling up the air column, rather than snapping the mouth corners forward toward the rim of the mouthpiece (not into

the cup of the mouthpiece), is one of the chief

causes of the unwanted neck puff (the pregnant

neck).

Over-breathing for the upper register causes dizziness, lightheadedness, spots before the eyes, pain

in the back of the head and neck, etc.

It is impossible to develop and maintain correct

breathing if the playing posture is faulty.

Excessive dropping of the jaw to produce a fine,

responsive lower register only adds to upper register difficulties and creates many unwanted endurance and flexibility problems.

A chin or lip vibrato can often become an unwanted

Everett Reinhardt Interview 4

playing fixture, so much,

that the performer can no

longer produce a so-called

straight tone. These two

methods of producing vibrato have often caused

facial nerve damage; I have

seen and heard hundreds

of such cases.

10. When a performers oral

cavity is extremely small

and the roof of the mouth

very low, very often an air

pocket will form in one

cheek or the other, or both,

or under the upper lip. This

type of player should avoid

any air pocket under the

lower lip, particularly if he

uses a high mouthpiece

placement (two-thirds upReinhardt with a transparent trombone mouthpiece of his own design

per lip, one-third lower).

The air pocket will become particularly prolip than upper is projected into the cup of the mouthnounced when playing loudly in the upper regispiece during the blowing. The higher the note being

ter. If this mannerism is not corrected, when the

played, the closer the upstream will strike toward

physical structure is as described, then the unthe rim of the mouthpiece; the lower the note, the

wanted neck puff will take over. I consider an air

closer it will strike toward the throat of the mouthpocket in the cheek or cheeks, or under the upper

piece, but not directly into the throat of the mouthlip (never under the lower lip) to be the lesser of

piece. Both downstream and upstream performers

two evils, if you choose to consider an air pocket

can be observed visually in a transparent plastic

an evil under the physical conditions already menmouthpiece. Metal rims without cups do not present

tioned.

a true picture of the performers lips while playing,

11. While using a plastic, transparent mouthpiece, I

because the actual blowing resistance which is crehave demonstrated and proven that those whose

ated by the use of both the mouthpiece and instrumouthpiece placement utilizes more upper lip than

ment positively cannot be duplicated with a metal

lower direct their airstream in a downward direcrim alone. Early in 1932, I lathed-out a transparent

tion into the cup of the mouthpiece, where (north

plastic mouthpiece and proved this point conclusively.

of the equator) it spirals its way in a counterclockSince that time, I have used this plastic visual source

wise manner through the cup, shoulder, throat,

as a basis for all my embouchure analyses and checkand backbore of the mouthpiece, and into the

ups.

leadpipe of the instrument. The downstream is

Limited time and space prevent me from discusscreated because more upper lip than lower is proing over a hundred basic playing points. However, I

jected into the cup of the mouthpiece during the

trust that the eleven points just discussed will problowing. The higher the note being played, the

vide you with some of the logic used in my Pivot

closer the downstream will strike toward the rim

System instruction.

of the mouthpiece; the lower the note, the closer

T.E.: What percentage of your students return for

to the throat of the mouthpiece, but not directly

regular lessons after your initial three-hour Orientainto the throat of the mouthpiece.

tion and Analysis period?

Conversely, the performers whose mouthpiece

D.R.: Approximately 95 to 96 percent of my stuplacement utilizes more lower lip than upper direct

dents return for regular lessons after my initial threetheir air streams in an upward direction into the cup

hour Orientation and Analysis period. Lessons are

of the mouthpiece, where it commences its spiral

never rostered until the performer has had a two to

through the cup, shoulder, throat, and backbore of

four-week incubation period following my initial

the mouthpiece, and into the leadpipe of the instruthree-hour presentation. This provides time for the

ment. The upstream is created because more lower

performer to settle down, study his entire personal 1974 Robert D. Weast. Revised version 2000 International Trumpet Guild.

Everett Reinhardt Interview 5

A Reinhardt trumpet student with an early transparent mouthpiece model used for analyses

ized presentation, study the Augmented Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, and make notes on the many

and varied questions which beset him during this

time. Only under the most unusual circumstances

with the students coming from foreign countries do I

ever make exceptions to these rules. The four or five

percent of the students who do not return for lessons

on a regular basis may be attributed to the following

reasons:

1. Most of my students are in the profession and they

are on the road with groups, bands, orchestras,

etc., and it is impossible for them to take lessons

on a regular basis. I have one student who has

been with me since 1954, and throughout his professional career we have kept in contact through

checkups, four to eight times a year. I have a

large group of students who fall into this category;

I call them the check-up group. The reasons for

them not taking regular lessons following my orientation and analysis period should be quite obvious.

2. My students come from all over the world, and

they manage to fit in a rather crammed course of

instruction during their once-a-year vacations

with me. During the interim, the telephone does

suffice. About 35 of my students fall into this category.

3. If a performer has a serious playing problem, but

must support his family and himself with his instrumental talents, and the adjustment cannot be

made under such circumstances, I tell him that I

will work with him during the first free time that

occurs in his professional work. In some cases, this

is both necessary and proper.

4. Some students have been sold some preconceived

idea that I would change their embouchures, and

they come in with a combination of fear and general mistrust. Some out-dated instructors who

know nothing about the Pivot System, but come

on as world authorities often spread these rumors. I wish to state in this regard that I have

changed only one embouchure since 1960, and this

was for Mr. Lyle Van Wie. This can be proven. He

insisted upon the change.

5. With some, my Orientation and Analysis period

alone is expected to cure their incorrect playing,

which they have been years in acquiring. I am

supposed to wave a magic wand and immedi-

1974 Robert D. Weast. Revised version 2000 International Trumpet Guild.

Everett Reinhardt Interview 6

ately erase their many brass playing sins. The

Orientation and Analysis period is exactly what

the title suggests. Oddly enough, this type of frustrated individual would not expect to have his

hernia removed and move around a Steinway piano the next day. This type does not return for

lessons on any basis, regular or irregular.

6. Some are so conceited regarding their super talents that they could learn nothing from anyone.

These are the self-made boys. This is another

type who, if they returned for lessons, would have

their ego seriously deflated. So, you never see or

hear from them again as a student or in the profession.

7. Some are just curiosity seekers and do not intend to ever become serious about study in the

first place.

8. I always tell the truth and some resent the truth.

I am honored when the public pays one of my students a compliment, however, I admit that I seldom do. It is my job to find the leak in the dike

and repair it, not to use the old trick of flattering

the student. Unfortunately, some instructors pull

this Superman build-up on their students. Fortunately, some play well in spite of their instructors.

See Also

Ralph Dudgeon. Credit Where Credit is Due: The Life

and Brass Teaching of Donald S. Reinhardt. International Trumpet Guild Journal, June 2000.

pp. 26-39.

About the Author: Serving as Director of Bands and

Director of the Jazz Program

at Harvard University for

almost thirty years, Tom

Everett has made many contributions to the instrumental music world. Founder

and first President of the

International Trombone Association, former Trombone

Editor of The Brass World,

he has contributed numerous articles on bass trombone repertoire and his Annotated Guide to Bass Trombone Literature (now in

its third edition) is the standard reference in the

field. As a performer, he has appeared at Carnegie

Recital Hall and was one of the first bass trombone

recitalists/specialists. He has commissioned and premiered over thirty original compositions by such composers as Gordon Jacobs, Walter Hartley, Samuel

Adler, Warren Benson, T.J. Anderson, and Frigyes

Hidas. Founder of the Harvard University Jazz Program, he is an authority on the evolution and personalities of the jazz trombone.

Special thanks to Robert D. Weast and Thomas G.

Everett for permissions; Ralph Dudgeon for photographs; the Streitwieser Foundation, Instrumentenmuseum, Schlo Kremsegg in Kremsmnster,

Upper Austria for photographs and permissions;

ITG Publications Editor Michael Caldwell and ITG

Journal Staff Editor Kim Stephans for editing; and

Stephen L. Glover for layout and production.

1974 Robert D. Weast. Revised version 2000 International Trumpet Guild.

Everett Reinhardt Interview 7

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- T104 - TM Style Guide - Version 2.0 Reva PDFDocument39 pagesT104 - TM Style Guide - Version 2.0 Reva PDFAntoniaNo ratings yet

- Solomon PDFDocument15 pagesSolomon PDFChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- How To Achieve Your Musical GoalsDocument6 pagesHow To Achieve Your Musical GoalsChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Week 6Document1 pageWeek 6Chunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Ethical Treatment of EmployeesDocument14 pagesEthical Treatment of EmployeesChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Solomon PDFDocument15 pagesSolomon PDFChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Part II of Your Final Project On Your NeighborhoodDocument1 pageGuidelines For Part II of Your Final Project On Your NeighborhoodChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Maqam: Middle Eastern Modal MelodyDocument2 pagesMaqam: Middle Eastern Modal MelodyChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Joseph N. Straus Introduction To Post-Tonal Theory Pages 36, 37Document2 pagesJoseph N. Straus Introduction To Post-Tonal Theory Pages 36, 37Chunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Studio BlueprintDocument1 pageStudio BlueprintChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Nectar 2 Help DocumentationDocument148 pagesNectar 2 Help DocumentationSigit Purwana YudhaNo ratings yet

- Weeks 5 6 Review Summer 2016Document4 pagesWeeks 5 6 Review Summer 2016Chunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Night and D Lead SheetDocument2 pagesNight and D Lead SheetChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Acoustics Final 3D Model Emanuel BurksDocument1 pageAcoustics Final 3D Model Emanuel BurksChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Week 4Document24 pagesWeek 4Chunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Mandingo Drum GroovesDocument2 pagesMandingo Drum GroovesChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Grading WMMC ProjectsDocument1 pageGrading WMMC ProjectsChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Standard Textbook by AminDocument196 pagesStandard Textbook by Amingermanikus1990No ratings yet

- Breathing Presentation Handout 7.15.11Document3 pagesBreathing Presentation Handout 7.15.11Chunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Big Band Orchestration JazzEd MagazineDocument6 pagesBig Band Orchestration JazzEd MagazineChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Lexus and The Olive Tree Summary PDFDocument6 pagesLexus and The Olive Tree Summary PDFChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics Review Summer 2016Document3 pagesMacroeconomics Review Summer 2016Chunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Economics Week 10 ReviewDocument1 pageEconomics Week 10 ReviewChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Saved? From What? Jul 8 2018Document3 pagesSaved? From What? Jul 8 2018Chunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Making Jazz Transcription Easier - A Step-By-Step ApproachDocument6 pagesMaking Jazz Transcription Easier - A Step-By-Step ApproachChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- The Penguin Book of Chess Positions PDFDocument86 pagesThe Penguin Book of Chess Positions PDFChunka Omar100% (1)

- Week 7 ReviewDocument2 pagesWeek 7 ReviewChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- LessonsDocument2 pagesLessonsChunka OmarNo ratings yet

- Hybrid - Polychord Chart (Answer KEY)Document3 pagesHybrid - Polychord Chart (Answer KEY)Chunka Omar100% (3)

- Hybrids1 (DK)Document2 pagesHybrids1 (DK)Chunka OmarNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sacred Book of The Hindus VolIIDocument422 pagesThe Sacred Book of The Hindus VolIIbhakta_paulo100% (2)

- The Toulmin Model of ArgumentationDocument2 pagesThe Toulmin Model of Argumentationandreaivydy1993No ratings yet

- 2001 - Tsoukas - Hatch - Complex ThinkingDocument35 pages2001 - Tsoukas - Hatch - Complex ThinkingFarkas ZsófiaNo ratings yet

- Module 13 Ethics Truth and Reason Jonathan PascualDocument5 pagesModule 13 Ethics Truth and Reason Jonathan PascualKent brian JalalonNo ratings yet

- CIDAM-gen MathDocument7 pagesCIDAM-gen MathJewel Shyne Estrada-LidayNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person: Common Biases and FallaciesDocument24 pagesIntroduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person: Common Biases and Fallacieslawrence calesterioNo ratings yet

- RM IprDocument98 pagesRM IprnikhilghnikiNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan in English For Academic and Professional PurposesDocument9 pagesLesson Plan in English For Academic and Professional PurposesShine CajeloNo ratings yet

- Bandwagon Fallacy: ExamplesDocument8 pagesBandwagon Fallacy: ExamplesEliasNo ratings yet

- Unit 4: Inference and Its Classification 4.1. On InferenceDocument10 pagesUnit 4: Inference and Its Classification 4.1. On Inferenceclydell joyce masiarNo ratings yet

- Section 1.4Document6 pagesSection 1.4Shirlyn Mae D. TimmangoNo ratings yet

- Rhinoceros AnalysisDocument4 pagesRhinoceros Analysisrupal aroraNo ratings yet

- Test 1: Non Verbal ReasoningDocument17 pagesTest 1: Non Verbal ReasoningVioleta Jovanovic0% (1)

- The Barber Paradox SolvedDocument5 pagesThe Barber Paradox SolvedIan Thorpe0% (1)

- Semantics Unit 11 - Part 1 0Document39 pagesSemantics Unit 11 - Part 1 0Jarallah Ali JarallahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 - Propositional LogicDocument66 pagesChapter 10 - Propositional LogicĐiền Mẫn NghiNo ratings yet

- MathematicsDocument16 pagesMathematicsrisliNo ratings yet

- Unit2-Notes Ai UpdatedDocument36 pagesUnit2-Notes Ai UpdatedDhivakar SenthilNo ratings yet

- ParadoxesDocument486 pagesParadoxesmcdropkicker100% (1)

- (R18A0506) Discrete MathematicsDocument62 pages(R18A0506) Discrete MathematicsSneha VermaNo ratings yet

- Lloyd, Geoffrey Ernest Richard - Polarity and Analogy - Two Types of Argumentation in Early Greek Thought.-University Press (1966)Document505 pagesLloyd, Geoffrey Ernest Richard - Polarity and Analogy - Two Types of Argumentation in Early Greek Thought.-University Press (1966)Bruna MeirelesNo ratings yet

- Probability Questions and Answers - TestDocument108 pagesProbability Questions and Answers - TestRavindra Babu0% (2)

- Faulty Logic / Reasoning: or What Is Wrong With This Statement?Document17 pagesFaulty Logic / Reasoning: or What Is Wrong With This Statement?Lyndel Queency LuzonNo ratings yet

- 00 Bit 11003Document9 pages00 Bit 11003dexjhNo ratings yet

- Political Thinkers of EnglandDocument75 pagesPolitical Thinkers of EnglandMitu BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - DSDDocument95 pagesUnit 1 - DSDSaravanan MurugaiyanNo ratings yet

- QUARTER 4 Week 1 Judge The Relevance and Worth of Ideasj Soundness of Authors Reasoning and The Effectiveness of The PresentationDocument39 pagesQUARTER 4 Week 1 Judge The Relevance and Worth of Ideasj Soundness of Authors Reasoning and The Effectiveness of The PresentationDennis Angelo ZabalaNo ratings yet

- CAT 2021 Slot 2Document53 pagesCAT 2021 Slot 2Harry EdwardNo ratings yet

- CC442 NAQAA Form 11Document3 pagesCC442 NAQAA Form 11MuhamdA.BadawyNo ratings yet

- Diagramming Arguments Asecond Technique For The Analysis of Arguments Is DiagrammingDocument5 pagesDiagramming Arguments Asecond Technique For The Analysis of Arguments Is DiagrammingputriarumNo ratings yet