Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Clinical Psychology Graduate Students Perceptions of Their Scientific and Practical Training A Canadian Perspective

Uploaded by

Pablo HerrazOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Psychology Graduate Students Perceptions of Their Scientific and Practical Training A Canadian Perspective

Uploaded by

Pablo HerrazCopyright:

Available Formats

Canadian Psychology

2010, Vol. 51, No. 2, 133139

2010 Canadian Psychological Association

0708-5591/10/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0018236

Clinical Psychology Graduate Students Perceptions of Their Scientific

and Practical Training: A Canadian Perspective

Daniel L. Peluso, R. Nicholas Carleton, and Gordon J. G. Asmundson

University of Regina

The scientist-practitioner model is the most commonly used training modality in Canadian clinical

psychology graduate programmes. Despite pervasive endorsement throughout Canadian psychology

programmes, there is a paucity of data available on Canadian student opinions of the models implementation. The current study assessed 134 students from 9 provinces with a 38-item questionnaire

developed by the Council of University Directors of Clinical Psychology for assessing students

perceptions about the quantity, quality, and breadth of science training in their clinical psychology

doctoral programmes. Most students described their programs as providing a mix of research and clinical

focus, with slightly more weight given to research. Science training was reported as very important to

students, with indications they receive a good amount of high-quality training in science. Moreover, there

was a high level of agreement between desired levels of science training and the science training

received. Implications for future research and training are discussed.

Keywords: clinical psychology, clinical psychology graduate training, clinical psychology graduate

students, scientist-practitioner model

documentation regarding the early history of applied psychology is

scant; however, it is widely held that training in professional and

clinical psychology was prompted by the ending of the Second

World War (C. R. Myers, 1970). At that time, the utility of applied

psychology had been demonstrated through successful selection, training, and rehabilitation of military personnel (Vipond &

Richert, 1977; Wright, 1974). Consequently, there was increasing

demand for applied psychology in education, government, and

health sectors. Clinical training in Canada was not geared toward

professional specialisation; that is, training was encompassing

and broad, offering students training in educational, industrial, and

counselling sectors (Conway, 1984).

The status of applied psychology amongst other academic disciplines was considered suspect, largely because the psychologists

of the day paid little attention to scientific research (Wright, 1969).

In an attempt to secure status and legitimize itself as a profession

in universities, psychology programmes began adopting stronger

scientific foci. The shift was so profound that professional and

applied areas were eventually relegated to an inferior status in

favour of rigorous science and research (Conway, 1984).

Growing concern over professionalization and the development

of professional training in psychology prompted the CPA to stage

the Opinicon conference in 1960. Despite efforts to the contrary,

the conference failed to address issues of professionalism and

training, focusing instead on developing the academic side of

psychology (Gibson, 1974). It was during the Opinicon conference

that psychology was defined primarily as a science and secondarily

as a profession. This stringent operational definition served to

widen the increasing gulf between scientists and professionals

(Conway, 1984).

In May 1965, the CPA sponsored the Couchiching Conference

on Professional Psychology. The primary purpose of this gathering

was to reformulate an operational definition of professional psy-

The primary goal of clinical psychology graduate programmes

in Canada, as expressed in many departmental mission statements,

is to train students according to the scientist-practitioner or Boulder model of training (Raimy, 1950). This model is geared toward

training students to adequately develop both scientific research and

clinical practise skills (D. Myers, 2007). Most programmes acclaim the model; however, each programme differs in the extent to

which the scientific or practical aspects of training are emphasised.

Moreover, incorporating a balance between research and clinical

training is indicated throughout the current Canadian Psychology

Association (CPA) guidelines for accreditation and ethical conduct

(CPA, 2002). The question of what proportion of focus should be

given to each aspect of training has been a subject of debate for

over 50 years (Aspenson et al., 1993; D. Myers, 2007). Some

Canadian researchers have argued that the scientist-practitioner

model is illusory and that each programme ultimately focuses on

whichever sidescience or practisethe programme sees fit to

emphasise (Conway, 1984).

To understand the status of the scientist-practitioner model in a

Canadian context, it is necessary to understand the developmental

history of clinical psychology training in Canada. The existing

Daniel L. Peluso, R. Nicholas Carleton, and Gordon J. G. Asmundson,

Anxiety and Illness Behaviours Laboratory, University of Regina.

Gordon J. G. Asmundson is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health

Research (CIHR) Investigator Award; R. Nicholas Carleton is supported by

a CIHR Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Research Award; and

Daniel L. Peluso is supported by a SSHRC Canada Graduate Scholarship

Masters Award.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Gordon

J. G. Asmundson, Anxiety and Illness Behaviours Laboratory, University

of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan, S4S 0A2. E-mail: gordon

.asmundson@uregina.ca

133

134

PELUSO, CARLETON, AND ASMUNDSON

chology. The vast majority of psychologists at this conference

advocated for a more balanced approach to training that would

emphasise both academic and applied facets of training. Despite

substantial agreement, many vocal professionals remained polarized on these issues. For example, some clinicians argued for a

professional training model resembling the PsyD programmes

found in the United States (Ewing, 1963; Sutherland, 1964), given

the low research productivity amongst professional psychology

graduates (Kelly & Fiske, 1950; Levy, 1962). By contrast, there

were ardent academics who argued that professional psychologists

were merely technicians, and advocated for a focus on rigorous

science (Conway, 1984). Despite such disagreements a consensus

was reached and the scientist-practitioner model leading to the

PhD was ultimately adopted (Webster, 1967). The clinician was

reconceptualized as a scientist-professional who should have the

ability to produce useful research. Training in clinical skills was

seen as important, but secondary to training in the theory underlying those skills. This second hierarchical consensus was likely

the result of therapeutic techniques regularly being invalidated

(Conway, 1984).

From 1965 to 1980, psychology programmes in Canada experienced an unprecedented growth. In a veritable explosion of

enrolment, psychology departments were rapidly becoming the

largest departments in many universities. Indeed, the number of

departments offering graduate programmes in psychology doubled

(Adair, 1981). Clinical psychology, as we know it today, experienced a rebirth of sorts as a result of psychologys rapidly bourgeoning popularity. In 1969, of the 29 professional graduate psychology programmes, 17 were in clinical psychology (Arthur,

1971), though these programmes were not accredited by the CPA,

and were substantially smaller in size than those that exist today;

currently, there are 23 CPA-accredited clinical programmes in

Canada.

The rapid expansion of clinical psychology resulted in regional

diversity regarding the adoption of the scientist-practitioner model.

For instance, French-speaking programmes in Quebec had larger

enrolments and were generally more practise-oriented than other

Canadian programmes (Conway, 1984). Furthermore, doctoral

programmes differed in the length of required internships, with

some institutions exclusively offering doctoral degrees (Conway,

1984). Reflecting this diversity in training, the relevance of the

scientist-practitioner model continued to be contested amongst

professionals and was not supported amongst nonacademic clinical

psychologists. The Boulder model was considered by some to be

culturally irrelevant to the Canadian context (Gibson, 1974), given

that the model was conceived in the United States, and would

therefore not reflect Canadian needs and culture (e.g., greater

contact between psychology and the community). As such, there

was a demand by some for a professional model that was tailored

to Canadian values and institutions. Davidson (1971) proposed the

researcher-consultant model that was designed to be more germane to Canadian psychology. This model advocated for a community psychology focus in which the psychologist would assess

the communitys needs, and subsequently develop and evaluate

programmes that were identified by the community (Davidson,

1981). Despite these efforts, a definition of a Canadian training

model was never fully developed; consequently, the scientistpractitioner model became the dominant training modality. Cana-

dian regions each met their own individual needs by altering the

model to fit their requirements.

The debate regarding Canadian training models continues today.

Despite the disagreements, empirical research on the scientistpractitioner model in Canada is scant. Indeed, implementation of

science training in clinical psychology programmes has not been

systematically studied (Merlo, Collins, & Bernstein, 2008). The

paucity of empirical research is made worse because student

opinions on the matter have largely been unsolicited. Preliminary

evidence suggests that American student opinions regarding the

scientist-practitioner model vary widely, with some being staunch

advocates and others describing it as a training anachronism

(Aspenson et al., 1993). More recently, the Council of University

Directors of Clinical Psychology (CUDCP)a nonprofit organisation whose purpose is to further graduate education in clinical

psychology programmes espousing the scientist-practitioner

modelinvited American and Canadian doctoral students to participate in a survey on their experiences. The researchers administered a rigorously developed CUDCP questionnaire to 611 clinical psychology students, assessing their scientific and practical

training experiences in doctoral programmes; however, the authors

provided no indication of the percentage of Canadian respondents,

if any. Results of that study suggest that students report a fairly

balanced emphasis on science and clinical work in their programmes (Merlo et al., 2008). These two studies represent the

extent of available data on scientist-practitioner models from a

student perspective; consequently, current understanding of student perceptions of their graduate programmes in clinical psychology remains limited.

Given the paucity of empirically driven research in this domain,

the purpose of the current study was to administer the CUDCP

questionnaire to a large sample of Canadian students and therein

assess their experiences with the scientist-practitioner model. The

current study will address three specific purposes. First, the results

will broaden our understanding of Canadian clinical psychology

students training experiences. This is crucial given that the data

available in this domain from the United States is difficult to

generalise to a Canadian sample because of differences which exist

amongst clinical and counselling programmes (and the unspecified

number of Canadian participants in the Merlo et al., 2008 study).

For instance, PsyD and counselling programmes do not figure

prominently in Canada, as there is only one PsyD programme

accredited by the CPA, and only four counselling programmes

are accredited by the CPA. Second, the information will provide

students with a summation of first hand experiences with scientistpractitioner models. Currently, students may unknowingly choose

programmes that are incongruent with their goals, thereby restricting their career paths because the relative emphasis on scientific or

practical aspects in graduate programmes is not explicitly stated

prior to enrolment (D. Myers, 2007). Third, the results will inform

existing Canadian clinical psychology programmes in Canada

about their own student perceptions.

Method

Procedure

Participants (N 136) were recruited from the CPA student

listserve via email. The distribution of sex was highly skewed,

TRAINING OF CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY STUDENTS

with 120 (88%) participants reporting being women (Mage 26.9;

SD 4.0) and only 16 (12%) reporting being men (Mage 30.4;

SD 6.3). This disproportion in gender is reflective of the overall

composition of graduate students, according to Canadian programme statistics as posted on programme websites. Students

interested in participating were directed to an online survey. Participation was restricted to clinical psychology students who were

currently enrolled in a clinical psychology programme in Canada.

Participants were informed that the study received ethical approval

from the University of Regina Research Ethics Board. Furthermore, participants were assured that all responses would be kept

confidential, and no identifying information was obtained from the

students. Education levels ranged from students in their first year

of graduate school through students in their eighth year or higher.

Program year distribution was as follows: 5% first year students,

25% second year, 17% third year, 15% fourth year, 18% fifth year,

10% sixth year, 7% seventh year, and 2% eighth year or above.

Approximately 9% of students did not disclose their year of study.

In terms of provincial representation, 52 (38%) of respondents

were enrolled in Ontario, 29 (29%) in Quebec, 17 (13%) in

Saskatchewan, 8 (6%) in Nova Scotia, 7 (5%) in British Columbia

and Manitoba, respectively, and 2 (1.5%) in each of Alberta,

Newfoundland, and New Brunswick. The sample was primarily

White (90%), with a smaller proportion of Asian (4%), South

Asian (1%), and Hispanic (2%) participants. Two (2%) participants endorsed the other category, and 13 (9%) chose not to

respond to the question.

Measures

Science training questionnaire. The current study employed

a 38-item questionnaire developed by the CUDCP Board of Directors to assess current students perceptions about the quantity,

quality, and breadth of science training in their clinical psychology

doctoral programmes (Merlo et al., 2008). The authors of this

questionnaire all serve as training directors of primarily scientistpractitioner programmes. The authors developed a detailed explanation of science training to be utilised in completing the questionnaire. Given that several competing perspectives on what

consists of science trainingas defined by each individual programme exist in the literature, the authors decided to employ a

more conventional definition of science. (Merlo et al., 2008).

Prior to questionnaire development, science was defined as:

All research-related instruction and activities. Some examples are: (1)

courses in research design, methodology and statistics, and philosophy of science, (2) required participation in research projects (e.g., a

formal, empirical Masters Thesis or other research projects), (3) a

focus on using empirically supported treatments/assessment techniques in clinical work, (4) participation in research projects being

conducted by faculty members, (5) opportunities to become involved

in conference presentations and manuscript preparation, (6) grantwriting or other related experience, and (7) a focus on critical analysis

and review of the literature.

These seven skills were seen to comprise well-rounded science

training in clinical psychology.

Participants responded to the questionnaire using a 5-point

Likert-type scale with three different response anchors ranging

from 1 (none, not at all, or very poor) to 5 (a great amount,

135

extremely, or excellent), depending on the particular question. To

tailor the questionnaire to Canadian students, the term qualifying

exams was changed to comprehensive exams, given that the latter

term is more frequently used in Canadian programmes. Sample items

corresponding to each response choice include, How much is science

emphasised/integrated in your programme as a whole?; How effective is the science training you receive for your comprehensive exams?; and Overall, how would you rate the quality of the science

training you receive in your graduate programme?

Results

Emphasis on Science Training: Overall Programme

and Specific Skills

The majority of students described their programs as providing

a mix of research and clinical focus. Scores ranged from 1 ( primarily clinical focus) to 5 ( primarily research focus). Approximately 47% of students reported that their programs training

emphasised clinical and research training equally, with a mean

score of 3.2. No students reported that their program had a strictly

clinical focus, whereas 5% reported an entirely research focus.

Students also described how much emphasis was placed on

seven different skill areas of traditional science training in their

programs. Results are shown in Table 1. Students typically reported that they received a good amount of training in these

specific science skills; however, more than a third (37%) of students indicated that they received a minimal amount of training in

grant writing, and almost a third (29%) reported a minimal amount

of training in research projects being conducted by faculty members. There were also statistically significant differences between

the years of education and the perceived focus on grant writing by

the programme, F(7, 119) 3.58, p .01, 2 .17. Based on

Tukeys post hoc comparisons, the first year students report receiving significantly more emphasis on grant writing than the

fourth, t(119) 3.75, p .01, r2 .11, fifth, t(119) 4.22, p

.01, r2 .13, and sixth, t(119) 3.48, p .05, r2 .09, year

students. There were no other statistically significant differences

between the groups and there were no other differences were found

based on students year of study in their program (all ps .05).

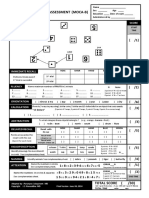

Areas of Traditional Science Training

Students were also asked to report how much science is emphasised in six areas of their clinical psychology training, and how

much they would like science to be integrated into these areas.

These results are provided in Table 2. The emphasis on scientific

training that students reported receiving differed significantly from

their desired emphasis in two areas, including clinical placement

and practicum, wherein students wanted more emphasis, t(125)

4.94, p .001, r2 .16, and research, wherein students wanted

less emphasis, t(125) 2.58, p .011, r2 .05.

Student Opinions of Traditional Science Training

Overall, the majority of students indicated that science training

was either fairly (44%) or very (19%) important to them. Only one

respondent reported that science training was not at all important,

whereas a substantial minority (19%) answered extremely impor-

PELUSO, CARLETON, AND ASMUNDSON

136

Table 1

Students Perceptions of the Amount of Training in Seven Science Skills

Skill

Required participation in

research projects

Involvement in conference

presentations and/or

manuscripts

Focus on critical

analysis/review of the

literature

Coursework in research

methodology, philosophy of

science, statistics, and so

forth

Focus on using empirically

supported treatments in

clinical work

Participation in faculty research

Grant writing or other related

experience

M (SD)

Minimum

maximum

scores

Mode

2(df)

1 (none)

%

2 (minimal

amount) %

3 (fair

amount) %

4 (good

amount) %

5 (great

amount) %

4.35 (0.84)

25

(3) 76.31

12

30

54

3.67 (0.92)

25

(3) 24.21

12

28

41

19

3.84 (0.87)

25

(3) 32.34

28

42

24

3.65 (0.86)

25

(3) 38.76

1%

29

46

15

3.96 (0.96)

3.09 (1.20)

15

15

4

2

(4) 64.69

(4) 17.92

1

8

7

28

21

25

37

24

34

15

2.91 (1.10)

15

(4) 45.56

39

21

26

Note. N 134. These results reflect responses to the Science Training Questionnaire (Merlo, Collins, & Bernstein, 2008).

p .01.

tant. In addition, most students indicated that they identify themselves as scientists fairly strongly (35%), very strongly (30%), or

extremely strongly (14%).

Effectiveness of Traditional Science Training

Most students reported that their science training is very

effective as indicated by chi-square analysis (see Table 3).

Specifically, areas of science training that were rated as being

the most effective were, in order, research, followed by program as a whole, coursework, and comprehensive exams; there-

after, elective coursework and clinical work were both rated as

equally effective. Regarding the quality of science training that

they receive, the mean score was 3.9; scores ranged from 2

( poor) to 5 (excellent). Ratings for quantity of science training

were also assessed, with a mean score of 3.9; scores ranged

from 2 ( poor) to 5 (excellent). Finally, students rated the

breadth of science training that they receive, with a mean score

of 3.6, and a range of 2 ( poor) to 5 (excellent).

There was no significant correlation between ratings of the

quality of science training and number of years of study (r .10,

Table 2

Discrepancies Between Received Versus Desired Emphasis on Science in Various Areas of Training

Area

M (SD)

Minimum

maximum

scores

t(df)

1 (none)

%

2 (minimal

3 (fair

4 (good

5 (great

amount) % amount) % amount) % amount) %

Received programme as a whole 4.12 (0.79)

Desired programme as a whole

4.00 (0.75)

25

25

t(126) 1.75, r2 .02

0

0

4

3

14

18

48

54

34

24

Received required coursework

Desired required coursework

3.95 (0.76)

3.95 (0.69)

25

25

t(126) 0.01, r2 .01

0

0

5

2

17

19

56

60

22

19

Received elective coursework

Desired elective coursework

3.57 (0.93)

3.73 (0.84)

15

15

t(123) 1.95, r2 .03

2

1

11

8

30

23

43

54

15

14

Received clinical work

Desired clinical work

3.38 (0.85)

3.76 (0.78)

15

25

t(125) 4.94, r2 .16

1

0

12

6

45

26

33

52

10

16

Received research

Desired research

4.51 (0.71)

4.33 (0.72)

25

25

t(125) 2.58, r2 .05

0

0

2

2

8

9

29

43

62

46

Received comprehensive exams

Desired comprehensive exams

3.79 (1.08)

3.73 (0.90)

15

15

t(118) 0.87, r2 .01

5

4

7

2

20

24

40

54

28

16

Note. N 134. These results reflect responses to the Science Training Questionnaire (Merlo, Collins, & Bernstein, 2008).

Significantly different after Bonferroni adjustment (Westfall & Wolfinger, 1997).

TRAINING OF CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY STUDENTS

137

Table 3

Perceived Effectiveness of Traditional Science Training

Area

SD

Minimum

maximum

scores

Programme as a whole

Required coursework

Elective coursework

Clinical work

Research

Comprehensive exams

3.59

3.49

3.28

3.28

3.98

3.37

.78

.77

.83

.90

.76

.93

15

15

15

15

25

15

Mode

4

4

3

3

4

4

2(df)

(4)

(4)

(4)

(4)

(3)

(4)

107.45

109.10

94.87

70.03

51.71

74.63

1 (none)

%

2 (minimal

amount) %

3 (fair

amount) %

4 (good

amount) %

5 (great

amount) %

1

1

2

2

0

5

6

7

13

16

2

9

35

42

48

41

25

38

48

43

31

34

47

41

9

7

6

7

26

8

Note. N 134. These results reflect responses to the Science Training Questionnaire (Merlo, Collins, & Bernstein, 2008).

p .01.

p .05). This suggests student perception of the quality of their

education remains fairly constant throughout their training. As

might be expected, there was a small but statistically significant

negative correlation between the quantity or amount of science

training and years of study (r .18, p .05). In contrast, there

was no significant correlation between ratings of the breadth of

science training and years of study (r .10, p .05). The

previous two results are somewhat counterintuitive, suggesting the

possibility that students may not perceive additional time spent

with scientific training as providing additional breadth; nevertheless, the quality, quantity, and breadth of training are all positively

correlated (all rs .60, all ps .01), suggesting that despite

student perceptions across time, students recognise the confluent,

supporting relationship of the three variables quality, quantity,

and breadth of science training.

Discussion

Science has formed the foundation of training and has retained

a position of paramount importance since the early years of clinical

psychology; it continues to be inextricably linked to the training

provided in doctoral clinical psychology programmes. The vast

majority of clinical psychology programmes in Canada espouse

the scientist-practitioner model. Even amongst programmes that do

not explicitly endorse such a model, science training is deemed to

be an essential part of graduate training. Despite pervasive endorsement of the scientist-practitioner model in Canada, there are

little data available on Canadian student opinions of the implementation of the scientist-practitioner model. The results of the

present study suggest that, in general, clinical psychology students

enrolled in Canadian programmes report feeling satisfied with the

level of science training they receive.

Consistent with previous research using a U.S. student sample

(Merlo et al., 2008), Canadian students reported that their training

was slightly more weighted toward research than clinical practise.

The overwhelming majority of Canadian students indicated that

they preferred a good amount of science training in their programmes, suggesting that most perceive science training to be an

integral aspect of their overall academic training. In addition,

Canadian students reported, with some exceptions, that both the

quality and quantity of the science training received was highly

congruous with their desired levels; thusly, it appears that training

programmes have been successful at integrating science into training to a degree that is consistent with student expectations. Al-

though students indicated that a fair amount of science training

was emphasised in clinical work (i.e., clinical placements and

practicum), they reported that this training was not very effective;

indeed, as 52% of students indicated that they would like a good

amount of science emphasis placed on their clinical work it appears that this is a training area in need of some modification.

Clinical work, according to this study, was defined as clinical

placements or practicum. It is difficult to determine why students

perceive their science training to be less effective in clinical

work. It may be that practicum sites are not adequately integrating science into the training programmes, according to students.

Given that practising clinicians rarely conduct research (Haynes,

Lemsky, & Sexton-Radek, 1987), it may be the case that science

is not seen as a priority. Conversely, it is possible that science is

not being effectively integrated into clinical work at the university

level, because some programmes offer practicum at their institution. In any case, clinical programmes may find it particularly

worthwhile to review these issues internally, including their own

graduate students and their experiences.

Regarding the breadth of science training, students were generally satisfied with the emphasis received in their programmes.

There was, however, an exception; nearly half of the students

reported receiving no training or minimal training in grant writing

or other related experience. It is reasonable to speculate that

student responses to this question included all funding applications

(e.g., grants, scholarships, bursaries); however, that speculation

necessarily overlooks the distinction between grant applications

which are typically more complex and scholarship applications

which are often relatively less complex. This finding was surprising, given the implicit importance of writing funding applications

in academia for the future success of both students and professionals. For example, students with funding place less strain on the

supervisors budget, leaving those resources to be allocated to

other areas such as research, conferences, and attracting future

students. Grants also provide funding for research, thereby increasing the likelihood of sustained funding, and ultimately, increasing

the probability of promotion in the academic field (Merlo et al.,

2008). Thusly, grant writing, and by extension funding, is important in generating and perpetuating research.

The difference may be the result of faculty assuming senior

students possess the analytical and writing skills necessary to

formulate a successful grant proposal and thusly are given less

instruction than more junior students, although this point is purely

138

PELUSO, CARLETON, AND ASMUNDSON

speculative. Conversely, it may be the case that junior students are

more likely to apply for scholarships because they have not yet

received them; in contrast, over time an increasing number of

students will have funding and not be continuing to apply. Lastly,

it may be that junior students are more likely than senior students

to seek out and attend to grant-writing instruction because of their

relatively lower levels of experience.

Limitations

There are limitations within the current study that are worth

noting. First, the study may have suffered from a sample bias,

given that the majority of provinces provided responses from only

two to eight students. For instance, in the case of British Columbia,

only seven respondents participated, a figure which is not representative of the number of students actually enrolled in clinical

programmes in that province. Consequently, results are difficult to

generalise for the entire province. Second, although only Canadian

student participants were solicited, no methods were employed to

confirm a participants nationality or student status; accordingly, it

is possible, though unlikely, that some of the respondents were not

students in Canadian clinical programs.

Limitations also exist with regard to the CUDCP questionnaire

itself. First, although rigorously developed, the questionnaire was

designed for American programmes espousing the scientistpractitioner model. Although Canadian programmes adhere to the

same model, it is possible that the questions may have been more

appropriate for American programmes. Moreover, the operational

definition of science that was adopted for the current study was

appropriated from the CUDCP. Thusly, it is possible that there is

divergence between American and Canadian programmes regarding what elements should be subsumed under science. Second, the

results of this study were not compared to the results of Merlo et

al. (2008). The Merlo et al. study did not exclude Canadian

participants; however, the percentage of Canadian respondents is

unknown. As a result, we feel that a direct comparison of the

countries would be inappropriate, and would not result in meaningful information. Fourth, the psychometric properties of the

CUDCP questionnaire have not been extensively assessed. Consequently, the results may not be robust. Fifth, the current data

does not provide details allowing discrimination between the additive and integrative effects of training. Future research should

attempt to explore whether these two dimensions of training can be

usefully delineated. Finally, it is possible that the current results

reflect a tautological relationship between student expectations and

Canadian psychology programs that acclaim the scientistpractitioner model. For example, students support of the Boulder

model might be a reflection of the fact that they have been

socialized into valuing research-based clinical training. Despite

these limitations, the results of this study warrant attention as they

currently represent the only explicitly Canadian data available on

this issue.

Implications for Future Research

Pervasive endorsement of the scientist-practitioner model in

Canadian clinical psychology programmes is limited by the current

lack of knowledge about its status or implementation. The results

of this study provide some insights on the Canadian implementa-

tion of the Boulder model via the perceptions of students. Students

were generally satisfied with the level of science trainingwith

grant writing and clinical integration being the two notable exceptions. Whether scholarship or grant-writing education is the responsibility of the department or incumbent on individual supervisors remains to be decided. Accordingly, future research should

explore this issue with students, supervisors, and departments. If

departments place responsibility for scholarship or grant-writing

training on faculty members, it may be beneficial for departments

to regulate this process through expert tutorials. Such tutorials may

foster a culture in which applying for funding is an expected part

of professional psychology. The finding that students are not

satisfied with the integration of science into their clinical work

presents some concerns given that science training is a requirement for CPA accreditation in clinical psychology programmes

and the Canadian Code of Ethics (CPA, 2002) stipulates that

practising psychologists must stay abreast with research. Moreover, this suggests that the scientist-practitioner model is not being

implemented as effectively as may be hoped, given that clinical

practise should be informed with relevant and up-to-date scientific

research. Future research should examine which aspects of integration are lacking. For example, students may feel that there is

insufficient emphasis on reading literature or attending scholarly

conferences to supplement clinical training. Given the myriad of

ways in which science could be integrated into clinical work,

greater specificity regarding which aspect of science integration is

ineffective appears warranted.

Finally, the vast majority of students indicated that emphasis on

science in their graduate training was very important; however,

students may not always readily perceive the cumulative value of

their training over time. The present study did not assess whether

students intend on continuing to integrate science into their clinical

practise after graduation. Future studies should determine how

important it is for students to incorporate science in their professional careers and, perhaps more important, how they intend on

doing so.

Conclusions

This study represents an important first step in determining the

status of the scientist-practitioner model in Canadian clinical psychology programmes. The research was exploratory and the results

preliminary. More information about the implementation of the

scientist-practitioner model is needed, from representative samples

of students as well as from faculty and directors of clinical training. Ultimately, it is our hope that these insights, once generated,

will be used to improve the quality of training in Canadian clinical

psychology programmes.

Resume

Le mode`le de formation scientifique-praticien est le plus courant

pour les programmes detudes superieures en psychologie clinique

au Canada. En depit dun puissant appui de par le pays au sein des

programmes de psychologie, il existe peu de donnees sur les

opinions des etudiants sur lapplication de ce mode`le. Dans la

presente etude, on a demande a` 134 etudiants de 9 provinces de

repondre a` un questionnaire de 38 items, elabore par le Council of

University Directors of Clinical Psychology, en vue devaluer

TRAINING OF CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY STUDENTS

lopinion des etudiants sur la quantite, la qualite et la portee de la

formation en science dans le cadre de leur programme de troisie`me

cycle en psychologie clinique. Selon la plupart des repondants,

leur programme est axe tant sur la recherche que sur le travail

clinique, la recherche beneficiant dun peu plus dimportance. Les

etudiants ont rapporte que la formation en science leur etait tre`s

importante et ont indique quils obtenaient une bonne dose de

formation de grande qualite dans ce domaine. En outre, le niveau

desire de formation en science equivalait, en grande partie, au

niveau recu. Sont examinees les reprecussions des resultats sur les

etudes ulterieures ainsi que sur la formation.

Mots-cles : psychologie clinique, formation des diplomes en psychologie clinique, etudiants diplomes en psychologie clinique,

mode`le scientifique-praticien

References

Adair, J. G. (1981). Canadian psychology as a profession and discipline.

Canadian Psychology, 22, 163122.

Arthur, A. Z. (1971). Applied training programmes of psychology in

Canada: A survey. Canadian Psychologist, 12, 46 65.

Aspenson, D. O., Gersh, T. L., Perot, A. R., Galassi, J. P., Schroeder, R.,

Kerick, S., . . . Brooks, L. (1993). Graduate psychology students perceptions of the scientist-practitioner model of training. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 6, 201215.

Canadian Psychological Association. (2002). Accreditation standards and

procedures for doctoral programmes and internships in professional psychology (4th Rev.). Retrieved from, http://www.cpa.ca/cpasite/userfiles/

Documents/Accreditation/Accreditation%20Manual%20Jan08.pdf

Conway, J. B. (1984). Clinical psychology training in Canada: Its development, current status, and the prospects for accreditation. Canadian

Psychology, 25, 177191.

Davidson, P. O. (1971). Graduate training and research funding in clinical

psychology in Canada (Special Report to the Science Council of Canada,

1970). Reprinted in Canadian Psychologist, 12, 141175.

Davidson, P. O. (1981). Some cultural, political and professional antecedents of

community psychology in Canada. Canadian Psychology, 22, 315320.

139

Ewing, R. M. (1963). Some thoughts on the education and training of

clinical psychologists. Canadian Psychologist, 4a, 5559.

Gibson, D. (1974). Enculturation stress in Canadian psychology. Canadian

Psychologist, 15, 145151.

Haynes, S. N., Lemsky, C., & Sexton-Radek, K. (1987). Why clinicians

infrequently do research. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 18, 515519.

Kelly, E. L., & Fiske, D. W. (1950). The prediction of success in the VA training

program in clinical psychology. American Psychologist, 5, 395406.

Levy, L. H. (1962). The skew in clinical psychology. American Psychologist, 17, 244 249.

Merlo, L. J., Collins, A., & Bernstein, J. (2008). CUDCP-affiliated clinical

psychology student views of their science training. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 2, 58 65.

Myers, C. R. (1970). Whatever happened to Canadian psychology? Canadian Psychologist, 11, 128 132.

Myers, D. (2007). Implication of the scientist-practitioner model in counselling psychology training and practice. American Behavioral Scientist,

50, 789 796.

Raimy, V. C. (1950). Training in clinical psychology. Englewood Cliffs,

NJ: Prentice Hall.

Sutherland, J. S. (1964). The case history of a profession. Canadian

Psychologist, 5a, 209 224.

Vipond, D., & Richert, R. A. (1977). Contributions of Canadian psychologists to the war effort, 1939 1945. Canadian Psychological Review,

18, 169 174.

Webster, E. C. (1967). The Couchiching conference on professional psychology. Montreal, Quebec: Canadian Psychological Association.

Westfall, P. H., & Wolfinger, R. D. (1997). Multiple tests with discrete

distributions. The American Statistician, 51, 3 8.

Wright, M. J. (1969). Canadian psychology comes of age. Canadian

Psychologist, 10, 229 253.

Wright, M. J. (1974). CPA: The first ten years. Canadian Psychologist, 15,

112131.

Received March 10, 2009

Revision received July 13, 2009

Accepted July 14, 2009

You might also like

- Public Psychology A Competency Model For Professional Psychologists in Community Mental HealtDocument11 pagesPublic Psychology A Competency Model For Professional Psychologists in Community Mental HealtPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Retratos Do Programa Saude Da Familia em Construcoes Discursivas de UsuariosDocument14 pagesRetratos Do Programa Saude Da Familia em Construcoes Discursivas de UsuariosPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Alarcon y Nauhuelcheo - Creencias Sobre El Embarazo, Parto y Puerperio en La Mujer MapucheDocument15 pagesAlarcon y Nauhuelcheo - Creencias Sobre El Embarazo, Parto y Puerperio en La Mujer MapuchePablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Public Engagement, Knowledge Transfer, and Impact Validity PDFDocument20 pagesPublic Engagement, Knowledge Transfer, and Impact Validity PDFPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Clinical Psychology Graduate Students Perceptions of Their Scientific and Practical Training A Canadian PerspectiveDocument7 pagesClinical Psychology Graduate Students Perceptions of Their Scientific and Practical Training A Canadian PerspectivePablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Clinical Psychology Graduate Students Perceptions of Their Scientific and Practical Training A Canadian PerspectiveDocument7 pagesClinical Psychology Graduate Students Perceptions of Their Scientific and Practical Training A Canadian PerspectivePablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Assessing Client Satisfaction in A Psychology Training Clinic PDFDocument10 pagesAssessing Client Satisfaction in A Psychology Training Clinic PDFPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Community Psychologists' Role in Shaping Transformative Public PolicyDocument13 pagesCommunity Psychologists' Role in Shaping Transformative Public PolicyPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- What Predicts Performance During ClinicalDocument19 pagesWhat Predicts Performance During ClinicalPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Public Engagement, Knowledge Transfer, and Impact ValidityDocument20 pagesPublic Engagement, Knowledge Transfer, and Impact ValidityPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Clinical Psychology Graduate Students Perceptions of Their Scientific and Practical Training A Canadian PerspectiveDocument30 pagesClinical Psychology Graduate Students Perceptions of Their Scientific and Practical Training A Canadian PerspectivePablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Community Psychology Training in Canada in The New Millennium PDFDocument7 pagesCommunity Psychology Training in Canada in The New Millennium PDFPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- LeVine-2010 - The Six Cultures Study. Prologue To A History of A Landmark ProjectDocument10 pagesLeVine-2010 - The Six Cultures Study. Prologue To A History of A Landmark ProjectPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Meijl - 2008 - Culture and Identity in AnthropologyDocument19 pagesMeijl - 2008 - Culture and Identity in AnthropologyPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Culture and Identitity in AnthropologyDocument26 pagesCulture and Identitity in AnthropologyClaudia Palma CamposNo ratings yet

- Dolphijn 2013 Meatify-the-Weak PDFDocument10 pagesDolphijn 2013 Meatify-the-Weak PDFPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Public Psychology A Competency Model For Professional Psychologists in Community Mental HealtDocument11 pagesPublic Psychology A Competency Model For Professional Psychologists in Community Mental HealtPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- O Di Giminiani - The Contested Rewe PDFDocument18 pagesO Di Giminiani - The Contested Rewe PDFJean-Baptiste BlinNo ratings yet

- Oakdale Course 2014 Fluent SelvesDocument166 pagesOakdale Course 2014 Fluent SelvesPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- LeVine-2010 - The Six Cultures Study. Prologue To A History of A Landmark ProjectDocument10 pagesLeVine-2010 - The Six Cultures Study. Prologue To A History of A Landmark ProjectPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Keller - Ecocultural Effects On Early Infant CareDocument30 pagesKeller - Ecocultural Effects On Early Infant CarePablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Sarah PinkDocument238 pagesSarah Pinkmajorbonobo88% (8)

- Bonelli - 2015 - To See That Which Cannot Be SeenDocument20 pagesBonelli - 2015 - To See That Which Cannot Be SeenPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Bowlby Attachment TheoryDocument44 pagesBowlby Attachment TheoryYeukTze90% (10)

- O Di Giminiani - The Contested Rewe PDFDocument18 pagesO Di Giminiani - The Contested Rewe PDFJean-Baptiste BlinNo ratings yet

- Polona - Maternal Studies. Beyond The Mother and The ChildDocument5 pagesPolona - Maternal Studies. Beyond The Mother and The ChildPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Burkhart - Hrdy - Schaik - Cooperative Breeding and Human Cognitive EvolutionDocument12 pagesBurkhart - Hrdy - Schaik - Cooperative Breeding and Human Cognitive EvolutionPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Bonelli - 2015 - To See That Which Cannot Be SeenDocument20 pagesBonelli - 2015 - To See That Which Cannot Be SeenPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Carsten - 1995 - The Substance of Kinship and The Heat of The HearthDocument20 pagesCarsten - 1995 - The Substance of Kinship and The Heat of The HearthPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Bowlby Attachment TheoryDocument44 pagesBowlby Attachment TheoryYeukTze90% (10)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Self-Awareness: Importance, Benefits, Tips and ExamplesDocument15 pagesSelf-Awareness: Importance, Benefits, Tips and ExamplesMaricar TorcendeNo ratings yet

- AutismDocument5 pagesAutismNader Smadi83% (6)

- TATA MOTORS Annual Report 2016 17Document7 pagesTATA MOTORS Annual Report 2016 17RAHUL GUPTANo ratings yet

- DSM-5 Anxiety InventoryDocument3 pagesDSM-5 Anxiety Inventorykim reyesNo ratings yet

- PWP Guide Highlights Role in Improving Mental WellbeingDocument16 pagesPWP Guide Highlights Role in Improving Mental WellbeingovaNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Psychology: Historical and Theoretical Background ofDocument22 pagesAbnormal Psychology: Historical and Theoretical Background ofHeinz Lopez Alvarez Jr100% (1)

- Beyond The Hedonic TreadmillDocument15 pagesBeyond The Hedonic TreadmillLeroy RiceNo ratings yet

- MMDST Power PointDocument24 pagesMMDST Power Pointloumelyn88% (8)

- Movie Analysis For 28 DayscheDocument4 pagesMovie Analysis For 28 DayscheChester Nicole70% (10)

- 7th Seme Class 2Document41 pages7th Seme Class 2Pranshu Prajyot 67No ratings yet

- Psychiatric Interview & Mental Status ExamDocument36 pagesPsychiatric Interview & Mental Status Examsarguss1493% (15)

- Happe 1994Document26 pagesHappe 1994alfigeba100% (1)

- SandasjkbdjabkdabkajsbdDocument3 pagesSandasjkbdjabkdabkajsbdM Rafif Rasyid FNo ratings yet

- HT Impact On Children 41081Document6 pagesHT Impact On Children 41081Relax NationNo ratings yet

- Confession of Shopaholic 2009Document2 pagesConfession of Shopaholic 2009JERUEL FRANZ TUDAYAN100% (1)

- NotesDocument5 pagesNotesMamta KalambeNo ratings yet

- Checklist ADocument1 pageChecklist ABarry BurijonNo ratings yet

- Depression - ArticleDocument3 pagesDepression - ArticleAmanina RohizadNo ratings yet

- Motivation Drives: and Human NeedsDocument11 pagesMotivation Drives: and Human NeedsPrincess Mae AlmariegoNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Working Memory Disorder InterventionsDocument14 pagesRunning Head: Working Memory Disorder Interventionsapi-160674927No ratings yet

- Beck's Depression ScaleDocument5 pagesBeck's Depression ScaleVitalia Putri PradanaNo ratings yet

- Referat EnglezăDocument3 pagesReferat EnglezămirabelaumbrelaNo ratings yet

- Armatas (2011) Techniques in CoachingDocument11 pagesArmatas (2011) Techniques in CoachingCallum Bromley100% (1)

- Jean Piaget's Influence on Education PsychologyDocument7 pagesJean Piaget's Influence on Education PsychologyJay Paul Casinillo100% (1)

- Protocolo Moca B InglesDocument2 pagesProtocolo Moca B InglesFrancisca Carreño GuzmánNo ratings yet

- Brown-2005-Sudarshan Kriya YogiDocument9 pagesBrown-2005-Sudarshan Kriya YogiPriscilla Barewey0% (1)

- What Is Behavioural Communication FinalDocument8 pagesWhat Is Behavioural Communication FinalVivek Khepar100% (3)

- Psychodynamics Explanation of OCDDocument10 pagesPsychodynamics Explanation of OCDRaya Tatum50% (2)

- Community Therapy OptionsDocument37 pagesCommunity Therapy Optionsapi-518552134No ratings yet

- Janie Jacobs Resume March 2019Document2 pagesJanie Jacobs Resume March 2019api-404179099No ratings yet