Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dishonest Acquisition

Uploaded by

maustroOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dishonest Acquisition

Uploaded by

maustroCopyright:

Available Formats

Dishonest Acquisition

Contents

1

2

Summary vs. indictable...........................................................................................1

Larceny....................................................................................................................1

1 Summary vs. indictable

Criminal Procedure Act 1986 (NSW)

Indictable offences have the maximum penalty prescribed in the offences.

Summary offences have maximum penalties under the Criminal Procedure Act.

Table 1 offences have a maximum penalty of 2 years, or $1100 (s 267).

Table 2 offences have a maximum penalty of 12 months, or $5500 (s 268).

Property offences

Most property offences are dealt with summarily.

Robbery, and burglary of at least $60 000, are indictable.

If the stolen property at least $5000, Table 1 applies.

If the stolen property is less than $5000, Table 2 applies.

If the stolen property is less than $2200, the maximum fine is $2200.

Car joyriding (s 154A) has a maximum penalty of 2 years, regardless of the cars value

(Criminal Procedure Act s 268).

2 Larceny

Larceny is a common law offence.

The Crimes Act s 117 provides a maximum penalty of 5 years.

The Confiscation of Proceeds of Crime Act 1989 (NSW) allows forfeiture and pecuniary

penalty orders.

Crimes Act s 117

Whosoever commits larceny, or any felony by this Act made punishable like larceny, shall,

except in the cases hereinafter otherwise provided for, be liable to penal servitude for five

years.

Sexual Assault

2 Larceny

2.1 Actus reus

Requirement 1: Property capable of being stolen

Property generally must be tangible (Croton).1

The following can be stolen:

Metal, glass and wood fixed to houses or land (Crimes Act s 139)

Trees (Crimes Act s 140)

Domesticated farm animals (Crimes Act ss 4, 126-131) (14 years)

Domesticated dogs, animals or birds, and fish in private waters (ss 132-133, 502-512)

Cash (Croton)2

Securities (Crimes Act s 134)

Gas (White).3

The following cannot be stolen:

Land, because it cannot be taken and carried away.

Fixtures, because they are part of the land.

Wild animals (Case of Swans;4 Blade v Higgs)5

Bank deposits, because they are intangible (Croton)6

Electricity, because it is intangible

Data, because they are intangible (Oxford v Moss).7

The following are dealt with elsewhere:

Abstracting electricity is prohibited under the Electricity Supply Act 1995 (NSW) s 64.

Misusing data is prohibited under the Crimes Act pt 6.

Infringing intellectual property is dealt with under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).

1 Croton (1967) 117 CLR 326, 330 (cash can be stolen, but bank deposits cannot).

2 Croton (1967) 117 CLR 326, 330

3 White (1853) Dears 203.

4 Case of Swans (1591) 7 Co Rep 15b.

5 Blade v Higgs (1865) 11 HLC 621.

6 Croton (1967) 117 CLR 326, 330

7 Oxford v Moss (1978) 68 Cr App R 183.

Sexual Assault

2 Larceny

Requirement 2: Property in possession of another

Possession requires (1) physical control, and (2) intention to maintain physical control.

The property does not need to be possessed legally (Anic, Stalianou and Suleyman).8

Employers and masters have constructive possession of property held by employees and

servants (Williams v Phillips).9

Larceny by clerks or servants is prohibited separately (Crimes Act s 156) (10 years).

The last person to possess goods may have constructive possession.

People may have constructive possession of goods on their land, even if unaware of them

(Hibbert v McKiernan).10

Requirement 3: Property taken and carried away (Asportation)

Any movement is sufficient (Wallis v Lane).11

At common law, keeping goods obtained by mistake is insufficient (Potisk).12

At statute law, it is an offence to dishonestly keep property innocently obtained

(Crimes Act s 124).

Requirement 4: Without the owners consent

It does not need to be against the owners consent (Middleton).13

Exploiting an electronic error does not constitute consent (Kennison v Daire).14

Breaching a licence will be without consent (Kolosque v Miyazaki).15

8 Anic, Stalianou and Suleyman (1993) 61 SASR 223, 29-33 (Bollen J; King CJ agreeing; Mohr

J semble) (SASC in Banco).

9 Williams v Phillips (1957) 41 Cr App 5.

10 Hibbert v McKiernan [1948] 2 KB 142.

11 Wallis v Lane [1964] VR 293, 295 (Herring CJ).

12 Potisk (1973) 6 SASR 389, 398 (Bray CJ).

13 Middleton (1873) LR 2 CCR 38, 54-55 (Bramwell B).

14 Kennison v Daire (1986) 60 ALJR 249 (Gibbs CJ, Mason, Wilson, Deane and Dawson JJ)

(HCA).

Sexual Assault

2 Larceny

2.2 Mens rea

Requirement 1: Intention to permanently deprive

Intention to return is not a defence (Crimes Act s 118).

Intention to exercise ownership is sufficient (Foster).16

Intention to return fungibles (e.g. money) is not a defence (Williams;17 Feely).18

Conditional return (e.g. return fraud) is not a defence (Lowe;19 Sharp).20

It is not a defence if the propertys value would be exhausted (e.g. travel tickets).21

It is not a defence if the propertys nature would be changed (Weatherstone;22 Smails).23

Requirement 2: Fraudulently or dishonestly

Fraudulently and dishonestly are interchangeable (Glenister;24 Macleod).25

15 Kolosque v Miyazaki (unreported, NSWSC, 17 February 1995) (a licence to take goods to

sales registers does not include placing food where they would spoil, or concealing goods

with intention to steal).

16 Foster (1967) 118 CLR 117, 121 (Barwick CJ) (HCA).

17 Williams [1953] 1 QB 660.

18 Feely [1973] 1 QB 530.

19 Lowe v Hooker [1987] Tas R 153, 157-158 (Cosgrove J) (it was not a defence to return

stolen goods a store for refunds).

20 Sharp v McCormick [1986] VR 869 (taking a motor part from work to see if it fit, with

intention to return if it did not fit, was not a defence).

21 Beecham (1851) 5 Cox CC 181.

22 Weatherstone (1987) 8 Petty Sessions Review 3729 (Street CJ) (welding metal rods

prevented the owner from using them again as rods).

23 R v Smails (1957) WN (NSW) 150 (cutting up railway sleepers prevented the owner from

using them as railway sleepers).

24 Glenister [1980] 2 NSWLR 597.

Sexual Assault

2 Larceny

Dishonesty is based on current standards of ordinary decent people (Feely).26

Dishonesty is based on morals (Weatherstone).27

Ghosh28 (rejected in Peters)29 held that dishonesty was determined objectively.

Peters30 held that dishonesty was determined subjectively (knowledge, belief, intent).

Weatherstone31 cited Baartman,32 which held that there must be fraudulent intent.

Requirement 3: No claim of right

The claim must be a genuine belief of legal (not moral) entitlement to property (not the

means to recover it), regardless of whether there is an actual legal entitlement. (Fuge).33

The belief need not be reasonable, but must be more than a colourable pretence (Fuge).

There may be a claim to property of equal value (e.g. money) (Fuge).

Property cannot be taken beyond the claim (Fuge).

For an accessory, the principal must have a genuine claim (Fuge).

The defence has an evidentiary burden, and the prosecution has a legal burden (Fuge).

25 Macleod (2003) 214 CLR 230.

26 Feely [1973] 1 QB 530, 538-539, 541 (Lawton LJ), approved in Peters (1998) 192 CLR

493 (HCA).

27 Weatherstone (1987) 8 Petty Sessions Review 3729 (Street CJ).

28 Ghosh [1982] 1 QB 1053 (English).

29 Peters (1998) 192 CLR 493 (HCA).

30 Ibid, but has not been applied in NSW.

31 Weatherstone (1987) 8 Petty Sessions Review 3729 (Street CJ).

32 Baartman [1998] NSWSC 653.

33 Fuge (2001) 123 A Crim R 310, 314-315 (Wood CJ at CL).

Sexual Assault

2 Larceny

A claim of right negatives the fraudulence or dishonesty in larceny (Langham;34 Walden)35

and dishonest obtaining of property (Love),36 or intend to defraud in fraud offences

(Kastratovic).37

The believed entitlement must be under Australian law, not Indigenous law (Re DPP).38

2.3 Larceny by bailee

A bailee may commit larceny (Crimes Act s 125), even in respect of a substitute for the bailed

property (e.g. money from selling the property, in breach of the bailment) (Slattery;39 Wall).40

Crimes Act s 125

Whosoever, being a bailee of any property, fraudulently takes, or converts, the same, or any

part thereof, or any property into or for which it has been converted, or exchanged, to his

or her own use, or the use of any person other than the owner thereof, although he or she

does not break bulk, or otherwise determine the bailment, shall be deemed to be guilty of

larceny and liable to be indicted for that offence.

The accused shall be taken to be a bailee within the meaning of this section,

although he or she may not have contracted to restore, or deliver, the specific property

received by him or her, or may only have contracted to restore, or deliver, the property

specifically.

2.4 Larceny by servant or employee

Masters and employers have constructive possession of property held by servants and

employees. Thus, servants and employees may commit larceny (Crimes Act s 156) (10 years).

34 Langham (1984) 36 SASR 48, 53 (King CJ).

35 Walden v Hensler (1987) 163 CLR 561, 571 (Brennan J).

36 Love (1980) 17 NSWLR 608.

37 Kastratovic (1985) 42 SASR 59.

38 Re DPP Ref No 1 of 1999 (2000) 10 NTLR 1.

39 Slattery (1905) 2 CLR 546.

40 Wall (1932) 32 SR (NSW) 171.

Sexual Assault

2 Larceny

Crimes Act s 156

Whosoever, being a clerk, or servant, steals any property belonging to, or in the possession,

or power of, his or her master, or employer, or any property into or for which it has been

converted, or exchanged, shall be liable to imprisonment for ten years.

2.5 Embezzlement

At common law, servants who received property for masters had possession and could not

commit larceny (e.g. bank tellers pocketing deposits). This is now prohibited by statute.

Employers and masters must not have constructive possession. If they do, the offence is

larceny by a clerk or servant (Crimes Act s 156; Hayward;41 Wright).42 Constructive

possession is created by the employees or servants actions (e.g. putting money in a till,

or placing property in the employers car).

Employees and servants must be bound to give the property to employers and masters

(e.g.

41 Hayward (1844) 1 C&K 518; 174 ER 919.

42 Wright (1858) 7 Cox CC 413.

You might also like

- Dishonest AcquisitionDocument27 pagesDishonest AcquisitionmaustroNo ratings yet

- Life InterestDocument285 pagesLife InterestabcdcattigerNo ratings yet

- Deng V Australian Capital TerritoryDocument79 pagesDeng V Australian Capital TerritoryToby VueNo ratings yet

- DeedsDocument141 pagesDeedsabcdcattiger100% (1)

- Study Guide 3 - Strict LiabilityDocument4 pagesStudy Guide 3 - Strict LiabilitykenricdassNo ratings yet

- Law On Trespass OverviewDocument3 pagesLaw On Trespass OverviewSabaTariq000No ratings yet

- Conflicts of LawDocument7 pagesConflicts of LawRicca ResulaNo ratings yet

- Wurridjal V Commonwealth: The Acquisition of Indigenous Property On Just TermsDocument18 pagesWurridjal V Commonwealth: The Acquisition of Indigenous Property On Just TermsAmad SetiawanNo ratings yet

- 04.20.23 Re Loeb & Loeb Tribunal NotificationsDocument80 pages04.20.23 Re Loeb & Loeb Tribunal NotificationsThomas WareNo ratings yet

- Schuyler County's Brief On Appeal: Schuyler County and Chemung County V William HetrickDocument57 pagesSchuyler County's Brief On Appeal: Schuyler County and Chemung County V William HetrickSteven GetmanNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument23 pagesAssignmentAbigail LimNo ratings yet

- Study Guide 4 - Strict LiabilityDocument3 pagesStudy Guide 4 - Strict LiabilitynolissaNo ratings yet

- Outline in Persons and Family Relations A.Y. 2021-2022Document26 pagesOutline in Persons and Family Relations A.Y. 2021-2022Khristin AllisonNo ratings yet

- In The Supreme Court of The United StatesDocument23 pagesIn The Supreme Court of The United StatesaptureincNo ratings yet

- Columbus Files Motion To Dismiss Bankruptcy Claim by Latitude Five25 OwnersDocument38 pagesColumbus Files Motion To Dismiss Bankruptcy Claim by Latitude Five25 OwnersWSYX/WTTENo ratings yet

- Erezo Vs JepteDocument4 pagesErezo Vs JepteJuris PasionNo ratings yet

- Estate of Nancy E. Rosenblatt, Deceased, Joseph Rosenblatt, Trustee v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 633 F.2d 176, 10th Cir. (1980)Document8 pagesEstate of Nancy E. Rosenblatt, Deceased, Joseph Rosenblatt, Trustee v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 633 F.2d 176, 10th Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Trusts Reading Guide 2016 Sem2Document16 pagesTrusts Reading Guide 2016 Sem2willNo ratings yet

- Obligations and Contracts: Agabin, P.A., Mestizo: The Story of The Philippine Legal System (2011), Chapter 7, Pp. 169-216Document36 pagesObligations and Contracts: Agabin, P.A., Mestizo: The Story of The Philippine Legal System (2011), Chapter 7, Pp. 169-216Adriana Del rosarioNo ratings yet

- CITY of WICHITA Plaintiff-Appellee V Brad HERSHBERGER Defendant-AppellantDocument39 pagesCITY of WICHITA Plaintiff-Appellee V Brad HERSHBERGER Defendant-AppellantbrancronNo ratings yet

- R V Hansen - (2007) 3 NZLR 1Document82 pagesR V Hansen - (2007) 3 NZLR 1Tali Vermont HarlimNo ratings yet

- The Period of The RuleDocument24 pagesThe Period of The RuleKoustubh MohantyNo ratings yet

- Treatise - False Arrest & Imprisonment Cases MarkupDocument19 pagesTreatise - False Arrest & Imprisonment Cases MarkupChemtrails Equals Treason100% (12)

- Property Rights OwnershipDocument10 pagesProperty Rights Ownershipnoname6No ratings yet

- Amicus Curiae Brief of Pacific Legal Foundation and Center For Constitutional Jurisprudence in Support of Petitioners, Marvin M. Brandt Revocable Trust v. United States, No. 12-1173 (Nov. 22, 2013)Document36 pagesAmicus Curiae Brief of Pacific Legal Foundation and Center For Constitutional Jurisprudence in Support of Petitioners, Marvin M. Brandt Revocable Trust v. United States, No. 12-1173 (Nov. 22, 2013)RHTNo ratings yet

- The Diary (Constitutional Law and Ghana Legal System Methods)Document274 pagesThe Diary (Constitutional Law and Ghana Legal System Methods)Abdul-Baki100% (1)

- Complicity HandoutDocument5 pagesComplicity HandoutAnonymous yr4a85No ratings yet

- 123213123Document58 pages123213123Boon LeeNo ratings yet

- Halsbury's Personal PropertyDocument61 pagesHalsbury's Personal PropertyMinisterNo ratings yet

- Curiel Motion For Return of PropertyDocument19 pagesCuriel Motion For Return of PropertyRICHARD HURLEYNo ratings yet

- PM Morrison Wins NSW Preselection Supreme Court CaseDocument35 pagesPM Morrison Wins NSW Preselection Supreme Court CaseMichael SmithNo ratings yet

- Course Syllabus in Persons and Family RelationsDocument34 pagesCourse Syllabus in Persons and Family RelationsMonaliza Lizts75% (4)

- TPA Notes Part 1Document75 pagesTPA Notes Part 1johnnycenanig123No ratings yet

- Ratten v. Queen, (1971) 3 WLR 930. - Section 6Document12 pagesRatten v. Queen, (1971) 3 WLR 930. - Section 6Sahil DhingraNo ratings yet

- Elias TOPA ProjectDocument19 pagesElias TOPA ProjectAnonymous QGqunvdLTaNo ratings yet

- Ucl Faculty of Laws LAW OF CONTRACT 2017-2018 DR Prince SapraiDocument4 pagesUcl Faculty of Laws LAW OF CONTRACT 2017-2018 DR Prince SapraiAnonymous yr4a85No ratings yet

- For Sunday Oct 25Document11 pagesFor Sunday Oct 25Ronnie RimandoNo ratings yet

- Persons Uribe OutlineDocument29 pagesPersons Uribe OutlineGemma RetubaNo ratings yet

- Civil Law - For PrintDocument34 pagesCivil Law - For PrintJayson CabelloNo ratings yet

- 18-07-19 Consumers' Reply in Support of PI MotionDocument664 pages18-07-19 Consumers' Reply in Support of PI MotionFlorian MuellerNo ratings yet

- YOHANA V ABBOUD The Ghana Law 1974 (Youhana V. Abboud) Pg. 201 - 226Document26 pagesYOHANA V ABBOUD The Ghana Law 1974 (Youhana V. Abboud) Pg. 201 - 226Priscilla AdzokoNo ratings yet

- Syllabus 1Document9 pagesSyllabus 1Anne Vernadice Areña-VelascoNo ratings yet

- Scottish Law Commission 1969Document71 pagesScottish Law Commission 1969HarryNo ratings yet

- Course Outline CLR1Document34 pagesCourse Outline CLR1Pam NolascoNo ratings yet

- Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Opposition To Defendants' Motion For Summary Judgment Date: April 26, 2010 Time: 2:00 P.M. Place: Courtroom of Judge PhillipsDocument30 pagesMemorandum of Points and Authorities in Opposition To Defendants' Motion For Summary Judgment Date: April 26, 2010 Time: 2:00 P.M. Place: Courtroom of Judge PhillipsEquality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- Regina V G and Another: (2003) UKHL 50Document31 pagesRegina V G and Another: (2003) UKHL 50fefeNo ratings yet

- Derry V PeekDocument25 pagesDerry V PeekAfia FrimpomaaNo ratings yet

- Civil LawDocument8 pagesCivil LawJoe SolimanNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Certiorari PetitionDocument76 pagesSupreme Court Certiorari Petitionsjlawrence95No ratings yet

- STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION. Outline of Topics With Cases. 2021 2022Document6 pagesSTATUTORY CONSTRUCTION. Outline of Topics With Cases. 2021 2022ben carlo ramos srNo ratings yet

- Gene Pool v. Coastal Harvest - Brief ISO MTDDocument19 pagesGene Pool v. Coastal Harvest - Brief ISO MTDSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Doc. 36 - First Amended ComplaintDocument222 pagesDoc. 36 - First Amended ComplaintR. Lance FloresNo ratings yet

- 1 contentLawTorts PDFDocument10 pages1 contentLawTorts PDFPulkitNo ratings yet

- Krell V Henry: Court of Appeal Vaughan Williams, Romer and Stirling LJJDocument8 pagesKrell V Henry: Court of Appeal Vaughan Williams, Romer and Stirling LJJTimishaNo ratings yet

- Failure To Lodge A Caveat Under Torrens System PDFDocument34 pagesFailure To Lodge A Caveat Under Torrens System PDFTjia TjieNo ratings yet

- United States v. Richard Joseph Todaro, 550 F.2d 1300, 2d Cir. (1977)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Richard Joseph Todaro, 550 F.2d 1300, 2d Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Property Outline 4-7Document8 pagesProperty Outline 4-7Jackie Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- PRIL Up Syllabus 011916Document10 pagesPRIL Up Syllabus 011916Kevin HernandezNo ratings yet

- Petition for Certiorari Denied Without Opinion: Patent Case 98-1151From EverandPetition for Certiorari Denied Without Opinion: Patent Case 98-1151No ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Be Your Own Boss PDFDocument233 pagesCareer FAQs - Be Your Own Boss PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs InformationTechnologyDocument178 pagesCareer FAQs InformationTechnologyxx1yyy1No ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Property PDFDocument169 pagesCareer FAQs - Property PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Accounting PDFDocument150 pagesCareer FAQs - Accounting PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Legal PDFDocument197 pagesCareer FAQs - Legal PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Save The World PDFDocument193 pagesCareer FAQs - Save The World PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs Banking CareersDocument181 pagesCareer FAQs Banking CareersTimothy NguyenNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Work From Home PDFDocument202 pagesCareer FAQs - Work From Home PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Sample Cover Letter PDFDocument2 pagesCareer FAQs - Sample Cover Letter PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Investment Banking PDFDocument170 pagesCareer FAQs - Investment Banking PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Financial Planning PDFDocument206 pagesCareer FAQs - Financial Planning PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Law (NSW and ACT) PDFDocument148 pagesCareer FAQs - Law (NSW and ACT) PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Sample CV PDFDocument4 pagesCareer FAQs - Sample CV PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Save The World PDFDocument193 pagesCareer FAQs - Save The World PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Investment Banking PDFDocument170 pagesCareer FAQs - Investment Banking PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Entertainment PDFDocument190 pagesCareer FAQs - Entertainment PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Sample CV PDFDocument4 pagesCareer FAQs - Sample CV PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Sample Cover Letter PDFDocument2 pagesCareer FAQs - Sample Cover Letter PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Christmas - Classical - Bach and Rachmaninoff MedleyDocument8 pagesChristmas - Classical - Bach and Rachmaninoff Medleymaustro100% (1)

- Career FAQs - Law (NSW and ACT) PDFDocument148 pagesCareer FAQs - Law (NSW and ACT) PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs Banking CareersDocument181 pagesCareer FAQs Banking CareersTimothy NguyenNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Entertainment PDFDocument190 pagesCareer FAQs - Entertainment PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Financial Planning PDFDocument206 pagesCareer FAQs - Financial Planning PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- Career FAQs - Accounting PDFDocument150 pagesCareer FAQs - Accounting PDFmaustroNo ratings yet

- The Sims - Build 3, 'Since We Met'Document9 pagesThe Sims - Build 3, 'Since We Met'maustroNo ratings yet

- Laputa - Main Theme (A Minor)Document10 pagesLaputa - Main Theme (A Minor)maustroNo ratings yet

- The Sims - Build 5Document12 pagesThe Sims - Build 5maustroNo ratings yet

- Commentary On Cases of BreachDocument46 pagesCommentary On Cases of BreachmaustroNo ratings yet

- The Sims - Build 5Document12 pagesThe Sims - Build 5maustroNo ratings yet

- Studio Ghibli - Ghibli MedleyDocument6 pagesStudio Ghibli - Ghibli MedleyNurul Ain Razali100% (14)

- Animal Abuse Reflection FeedbackDocument3 pagesAnimal Abuse Reflection FeedbackHailey5667No ratings yet

- Anti Death Penalty EssayDocument2 pagesAnti Death Penalty EssayLauren NovakNo ratings yet

- Soriano Vs DizonDocument2 pagesSoriano Vs DizonCarlos JamesNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Essentials of Criminal Justice 10th EditionDocument9 pagesTest Bank For Essentials of Criminal Justice 10th Editiondermotkeelin7pkyNo ratings yet

- RPC - Book II. by TitleDocument4 pagesRPC - Book II. by TitleErmawooNo ratings yet

- Juvenile Delinquency Midterm EssaysDocument8 pagesJuvenile Delinquency Midterm EssaysJake100% (4)

- People v. TiongsonDocument13 pagesPeople v. TiongsonMIKKONo ratings yet

- Contemporary Womens Health Issues For Today and The Future 5th Edition Kolander Test BankDocument11 pagesContemporary Womens Health Issues For Today and The Future 5th Edition Kolander Test Bankalanholt09011983rta100% (36)

- Sociological Research Paper OutlineDocument5 pagesSociological Research Paper Outlinefvja66n5100% (1)

- Changing Dimensions and Scope of Criminal Law-Judicial PerspectiveDocument17 pagesChanging Dimensions and Scope of Criminal Law-Judicial PerspectiveParth TiwariNo ratings yet

- Deterrence Theory PDFDocument5 pagesDeterrence Theory PDFsrk1606No ratings yet

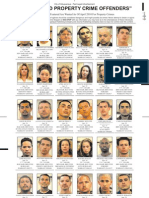

- Prop Crime 042010Document1 pageProp Crime 042010Albuquerque JournalNo ratings yet

- RPC CodalDocument14 pagesRPC CodalVitorrio Un100% (2)

- USPCDocument304 pagesUSPCZyza Gracebeth Elizalde - RolunaNo ratings yet

- Tanega V MasakayanDocument1 pageTanega V MasakayanNElle SAn Full100% (1)

- Information For Murder Check Downloaded SampleDocument2 pagesInformation For Murder Check Downloaded SampleJan Paul CrudaNo ratings yet

- Arrest Affidavit For Joseph TejedaDocument2 pagesArrest Affidavit For Joseph TejedacallertimesNo ratings yet

- Anti-Vawc RA 9262: Prepared byDocument15 pagesAnti-Vawc RA 9262: Prepared byBong ClaudioNo ratings yet

- Maine Inmate Search Department of Corrections LookupDocument3 pagesMaine Inmate Search Department of Corrections LookupinmatesearchinfoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To DevianceDocument7 pagesIntroduction To DevianceAtreides90No ratings yet

- Peoria County Booking Sheet 08/22/13Document8 pagesPeoria County Booking Sheet 08/22/13Journal Star police documentsNo ratings yet

- Crim 2 Cases 1st BatchDocument49 pagesCrim 2 Cases 1st BatchjumpincatfishNo ratings yet

- 10 BJP Rapist LeadersDocument7 pages10 BJP Rapist LeadersTushar SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Psychology Comer 8th Edition Test BankDocument51 pagesAbnormal Psychology Comer 8th Edition Test Bankgloriya100% (1)

- Coradmin 2013 ADocument11 pagesCoradmin 2013 AMa. Tiffany T. CabigonNo ratings yet

- On or About 12 Midnight of June 16, 2021 at Kagandahan Dormitory Legarda St. Barangay 410, Sampaloc, Manila Wherein VDocument4 pagesOn or About 12 Midnight of June 16, 2021 at Kagandahan Dormitory Legarda St. Barangay 410, Sampaloc, Manila Wherein VPCpl J.B. Mark Sanchez90% (10)

- Articles On TortureDocument5 pagesArticles On TorturesamNo ratings yet

- 20 Sagar Sudhakar Shendge V Naina Sagar Shendge Husband Can Be Arrested For Nonpayment of MaintenanceDocument4 pages20 Sagar Sudhakar Shendge V Naina Sagar Shendge Husband Can Be Arrested For Nonpayment of MaintenanceParivar ManchNo ratings yet

- (U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictDocument5 pages(U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictFauquier NowNo ratings yet

- SS11Document16 pagesSS11Kzandra KatigbakNo ratings yet