Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Botswana Media Studies Papers Vol 1

Uploaded by

RichardRooneyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Botswana Media Studies Papers Vol 1

Uploaded by

RichardRooneyCopyright:

Available Formats

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

THE BOTSWANA MEDIA

STUDIES PAPERS

A Collection Presented by the Media Studies

Department, University of Botswana

Volume One

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

The Media Studies Papers

A Collection of Papers Compiled by the

Media Studies Department, University of

Botswana

Edited by Richard Rooney

Published by The Media Studies

Department, Faculty of Humanities,

University of Botswana, Private Bag 703,

Gaborone, Botswana

www.ub.bw

2014. Copyright remains with individual

contributors

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

Contents

Introduction

By Richard Rooney .

The Local Print Magazine Industry in Botswana

By Martha Mosha ..

Corporate Social Responsibility and Community Development in Botswana: An

Analysis of the Perspectives of the Beneficiaries

By Divya Nair ..

16

The Juxtaposition Between Media Literacy and Democracy

By Penelope Kakhobwe

24

Capturing the Elusive Art: The Making of a Dance Film

Case Study: The Wandering Souls of Mendi

By Tiny Constance Thagame .

41

The Dilemma of Local Content: the Case of Botswana Television (Btv)

By Bokang Greatness Ditlhokwa .

53

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

Introduction

By Richard Rooney

This is a collection of papers originally

presented at a series of research seminars

hosted by the Department of Media

Studies in the Faculty of Humanities at the

University of Botswana during September

to November 2013.

The work presented recognises the wide

spectrum of teaching and research that

takes place within the department; ranging,

in this collection, across print media,

independent television production, the

representation of dance on film, corporate

social responsibility and development and

media literacy.

The Media Studies Department is the

major centre in Botswana for the teaching

of vocational and theoretical media. It runs

two undergraduate programmes in Media

Studies and intends to launch a Masters

programme in the not-too-distant future.

highlights the various challenges posed by

the inadequate capacity of the grant

managing institutions and the poor

networking

among

the

various

nongovernmental organizations.

Penelope Kakhobwe explores the

correlation which exists when it comes to

media

literacy

democracy

and

development. She makes a case for media

literacy for all and not just high school

children but all sectors of society through

cooperation

with

various

nongovernmental organisations in the field.

She examines this in a case study of

Malawi and concludes that it is the norm

in African countries for media personnel to

suffer persecution for their views.

Tiny Constance Thagame, using a

documentary film The Wandering Souls of

Mendi, she herself directed, investigates

the differences and similarities between

dance and film. She explores some of the

technical and philosophical aspects of

documenting dance. The study explores

the relationship between the choreographer

and the filmmaker, and how they can work

together to produce a successful dance

film.

Martha Mosha investigates the key

elements in the Botswana print magazine

production industry. Her broad research is

aimed at exploring elements such as

market, failures and successes of

magazines, advertising in the magazines,

printing, circulation, and publishers, using

secondary sources as the methodology.

Divya Nair investigates the relationship

between corporate social responsibility

(CSR) and community development in

Botswana. Her study, based on field work

in Botswana, analyses the role played by

grant managing institutions in delivering

CSR and the perspectives of the

beneficiaries in this respect. The study

Bokang Greatness Ditlhokwa reports that

contrary to the notion that Botswanas

independent television producers lack the

professional skills to generate local

television content, lack of finance is

arguably the main challenge that continues

to bedevil the producers. His research

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

reveals that the local state broadcaster

Botswana Television (Btv) continues to

make

attempts

to

empower

the

independent producers through licensing

of existing intellectual properties, but that

it lacks the necessary and transparent

guidelines to acquire television content.

We hope this will be the first of a series of

publications documenting the research

work of the Media Studies Department,

and we hope to present a further selection

of papers later in 2014.

Richard Rooney, February 2014

About the author

Richard Rooney is head of the Department of Media Studies at the University of Botswana.

He has taught in universities in Europe, Africa and the Pacific. His research, which

specialises in media and their contribution to democracy and good governance, has been

published in books and academic journals across the world.

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

The Local Print Magazine Industry in

Botswana

Martha Mosha

Abstract

Magazines as a means of communication like any other form of media perform two basic

functions; to inform and entertain by mixing news, stories and features. This is to ensure an

in-depth coverage and follow up stories. The purpose of this study is therefore to investigate

the key elements in the Botswana print magazine production industry. This broad research is

aimed at briefly looking into elements such as market, failures and successes of magazines,

advertising in the magazines, printing, circulation, and publishers, using secondary sources as

the methodology.

Keywords: magazine, media, print industry, Botswana

Magazines are a bit more narrow in

focus compared to the other available

media.

Kobak (2002) notes that magazine

production involves three functions;

Editorial - developing an editorial

product that would appeal to a target

readership.

Circulation - marketing the developed

product to the public.

Advertising - marketing the product

through highly sophisticated selling

methods to a small number of advertisers

who want to reach the public that reads the

produced magazine.

As such, the search is to focus on the

magazine production industry in Botswana

with the three functions as a guide. Other

peripheral issues will be looked into such

as a brief history of magazine production

in Botswana, the failure of magazines in

Botswana, and the dynamic magazine

Introduction

This research is a comprehensive look into

the magazine industry in Botswana, from

the first produced magazine to the present

day. Magazines are a periodical

publication containing articles and

illustrations, typically covering a particular

subject or area of interest (Angus

Stevenson, 2005).

Magazines

are

a

means

of

communication like all other media meant

to fulfil two basic human needs; to inform

and to entertain. According to Katz (2003),

magazines are commonly used to find

out more about our favourite hobbies and

interest. They offer a mixture of news,

stories and features thus they can be used

for in-depth coverage and subsequent

follow-up stories. A magazine is, usually,

less ephemeral than a newspaper, less

permanent than a book. (McKay, 2006)

According to Duffy and Turow (2009),

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

market in Botswana, so as to paint a

holistic picture of the industry. What shall

be discussed is biased to traditional printed

magazines, as this is the dominating

magazine form available at the time of this

research.

Lobatse. This was at the time one of the

very few printed materials written with

content aimed at Batswana. Prior to this

was a quarterly journal which was

produced during the 1930s (Government

of Botswana, 1999) named Lobone lwa

Betswana. Years would follow before the

establishment of another magazine within

the country.

There have been a limited number of

largely unsuccessful attempts to start

magazines. A few general interest

magazines were started in the past five

years, including Dumela (Hello) and Flair,

but all folded after a year or two. Most of

the surviving magazines are specialist ones

covering business and finance, the

environment, agriculture and mining.

(Sechele, 2006)

Statement of Problem

Magazine production in Botswana is an

industry that keeps growing, more and

more magazines are set-up every year, but

little is documented about such a key

industry in Botswanas media landscape.

Objectives

The purpose of this study is to investigate

key elements in the local print magazine

production industry.

Research Questions

The research questions, which govern this

study, are;

What is the current scene in terms of

the local magazine production market in

Botswana?

What are the issues faced by the local

magazine production companies?

Magazines in General

How the magazine industry works is

written in the simplest form by O'Connor

(2013) as;

A clever editor wishes to communicate

an insight. They put words and pictures on

pieces of paper, and find people to read

this content. Once you get enough readers,

then hopefully advertisers wish to engage

with this content.

To do all the above, a team is put

together under one company and thus

know as a magazine production company.

There are many ways to classify what is

known and referred to as a magazine.

Categorisation of magazines differs from

country to country. (De Beer, 1998)

Added to this different researchers

distinguish them with different terms, most

of which are highly dependent on the

different magazines available within a

given market. In the case of Botswana,

there are three main types of magazines

namely;

Literature Review

Botswana Magazine Research

Conducting research on media in

Botswana is very difficult let alone a

research in one such microscopic area as

magazine production. This is so the case as

Botswana has no independent media

research institution. (Sechele, 2006)

Added to this, most other research done on

media in Botswana looks primarily at

radio, television and newspaper. Often, the

term newspaper is used to represent all

other print media including magazines,

newsletters and advertisers.

Magazine production in Botswana

began in 1962 with the production of the

first copy for the then Bechuanaland

Government information branch in

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

Consumer - these have content aimed at

leisure information and hence offer

entertainment to the reader. This is used to

convey

information,

advice

and

entertainment.

more for a fully operational and wellestablished magazine.

Circulation

Circulation in this case refers to the

distribution methods of magazines once

produced. Thus circulation in terms of

ways in which the magazine gets to its

desired audience. Equally important is the

number of copies sold of a given

magazine, which shares the same name but

is not the one in reference.

There are a number of different ways

that magazine circulation types are

categorised internationally. The types of

circulation available in the magazine

industry in Botswana are;

Business-to-business also referred to

as trade or business and professional.

These magazines have content in

connection to the working industry. Its

content is geared at providing information

for a great mass in a targeted audience.

Consumer specialist the content in

such magazines is aimed at a specific field

of interest.

Consumer magazines make up the

largest sector of the industry in most

countries and this fact is not any different

in Botswana.

Paid circulation these include sales

from newsstands (at supermarkets,

bookstores, quick shops), single copy

sales, single paid subscription and multiple

sales (airlines, hotels, clubs).

Editorial

There is a lot of teamwork that goes

into the production of a magazine. This

includes the work of writers, editors,

graphics

designers,

photographers,

printers, and distributers, to name but a

few.

Some magazines opt to outsource some

of the services needed to produce a

magazine while others carry out

everything in-house. Some authors such as

Evans (2004), suppose that due to the

technological

advances,

magazine

production can be a one-person business.

This is mainly due to the fact that most of

what is needed is based around desktop

publishing. This is a great method to

starting up a business without having to

search for finances for starting up the

business. Thus, one can have as minimum

a staff complement until the magazine

takes off then thus employ a full team once

the magazine is fully functional.

However, Evans (2004) goes into

listing a staff compliment of about 35 or

Society/Association circulation this

can be done in certain circumstances such

as being a member of a given

society/association and belonging to given

institution. In some cases, these are for

given for free to members of a

society/association while at times free

means it is added to the membership fee.

Controlled circulation - this refers to

magazines that are circulated to a limited

mailing list. These include the specialised

magazines, which aim at a particular

industry. In large organisations, these

magazines could be produced internally

and meant for internal use- to

communicate to the staff information

about the organisation.

Advertisements

In order to solicit advertisers, magazine

production companies are meant to

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

conduct periodic research on their

audience. Armed with information from

the research, the magazine companies are

meant to convince potential advertisers

with statistics that enable them to make an

informed decision. In the case of

Botswana, very few magazines companies

have conducted such research. Most rely

on guesswork to understand who their

audience is. This constitutes to difficulty in

convincing other companies to advertise

with the magazine.

It is however a fact that, media

coverage and recommendations are

relevant for the commercial success of

products and services (Rinallo and

Basuroy, 2009) and with this in mind,

most companies in Botswana do agree to

buy advertisement space in selected

magazines hoping to gain success in sales

on their products and services in return.

Magazine advertisements in this

research looks at a broader picture, thus

including commercials and advertorials.

Magazines have succeeded amid strong

competition from other media vying for

advertising revenue, largely because of the

ability of magazines to reach specialised

audiences and to retain their interest. (De

Beer, 1998)

The average editorial-to-advertising

ratio of U.S. magazines is 56/44(McKay,

2006). This is a significant number- almost

50 percent of the content. Some authors

argue that advertisements are as much a

relevant part of the magazine as is the

editorial content (Rosengren and Dahln,

2013). In the case of some magazine in

Botswana, this figure may be above 44

especially if one removes the negative

space, used to fill up a story as some

magazine have adapted the use of negative

space to make a story with little written

content, fill up a page.

To a great extent advertisers have

had, and continue to have, greater

influence on what gets featured in

magazines than they do in newspapers.

(Clark 1988:345 in McKay (2006)). This

has led to a new way of thinking.

It is predicted that in future, advertising

content would be dependent on the

editorial content (Rosengren and Dahln,

2013). This would be so the case, as there

seems to be a high influence of advertising

content on the perception of a magazine.

Rosengren and Dahln (2013) elaborates

further and state that, perceptions of

the same advertisement can change due to

the editorial content surrounding it.

The following was found out to be true

in terms of advertisement in magazines

according to Rinallo and Basuroy (2009);

(1) Publishers that depend more on

a specific industry for their advertising

revenues are prone to a higher degree of

influence

from

their

corporate

advertisers than others; (2) peer

pressures from competing publishers

affect coverage decisions; (3) larger and

more innovative companies have an

advantage in obtaining coverage for

their products

This situation exists in the case of

Botswana and is made worse by the fact

that the potential advertisers in a given

industry such as cellular phone providers

or discount stores, are limited in number

and due to the lack of competition at any

given industry, which could advertise

within a given magazine.

Many magazines provide a wealth of

information through their adverts

(McKay, 2006). This is not an exception in

terms of the magazines produced in

Botswana. Most are packed with

information that fully elaborates on a

product or service.

However, Hurman (2013), argues that

advertising in magazines does not work

anymore - it is not effective. He says,

There's a discipline required to create

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

The editorial content ceases to

interest the market;

Circulation

being

pushed

beyond its natural levels.

The magazine has lost its

direction and hence is now not

serving the initial target market;.

Failure to compete with other

magazines in the industry;

Weakness in circulation efforts;

Weakness in advertising efforts;

Lack of control in managing

profits;

The reader is given too little or

too much content;

Pricing is too aggressive or not

aggressive enough;

Poor to none planning and

research.

According to Katz (2003), magazine

success is assessed in terms of their

circulation. However, McKay (2006)

states that, Circulation differs from

readership because a copy of a magazine

will almost certainly have more than one

reader. Thus, circulation is an average

indication of how many people actually

read a given magazine and hence its

success. This being the case, there are a

number of ways in which magazines can

be circulated.

For a magazine to be successful, there

is a need to have the right idea at the right

time, offering information or editorial

service that appeals to a sufficient number

of potential readers who in turn appeal to a

sufficient market of advertisers (Click

and Baird, 1983). Only by striking the

right balance would the industry in

Botswana stabilise and hence reduce the

failure rate that currently exists.

In the end De Beer (1998) explained

this balance in another way by stating that,

The ability to use the most modern

technology, research and knowledge

available has played a vital role in

world-class magazine advertising that just

doesn't exist in other mediums. As such,

his argument is that the creativity is

declining over the years. It goes without

saying that the decline in creativity results

in the audiences perception of an advert

becoming annoying. This would in turn

create a negative attitude by the readers

towards advertisements.

Failure in Magazines

There are more than 250 registered

magazine companies in Botswana.

According to the office responsible for

issuing out International Standard Serial

Number (ISSN), a unique number used to

identify publications, there are about 10 or

so magazines that apply for the number per

year. Application involves producing at

least one issue of the magazine as a

sample. Only about 20 percent of those

that apply end up in producing beyond the

submitted issue with more than 50 percent

of the applicants not returning to collect

the issued code at all. This shows that

there is a failure in the local magazine

production industry, which translates, to

the need to look into this area during the

research so as to figure out if this

phenomenon can be explained.

Williams (2004) attributes the secret of

success in print to be; intensive sales, in a

limited geographic area and to a welldefined (targeted) clientele or targeted,

specialised,

and

easily

identified

readership. This may seem simple enough

but in the case of Botswana, with a total

population of almost two million, the

market in question is very small in

number.

There are a number of reasons for

magazine failure. According to Kobak

(2002), the reasons include but not

limiting;

The decline in the target market,

reduced readership;

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

ensuring the future of magazines. There is

not much done in terms of research in the

area of magazines in Botswana hence this

is a huge obstacle for most production

companies. The issue on using modern

technology is mostly utilised as best but

not in terms of digital publishing. This is

yet to be a standard for most magazine

production companies. The only weapon

that the magazine production companies

have in Botswana is the knowledge of the

magazine industry in the country. Most

magazine editors would agree that this is a

very different unique, industry compared

to other magazine production industries

from other nations.

Since not much is written in terms of

the magazine production industry in

Botswana, there was a need to read

literature from other countries and gauge if

this is the case in terms of the industry in

Botswana.

Empirical Study

A number of empirical methods were

used to get the information needed. Due to

the fact that most organisation where the

needed information was to be found did

not have such information on record,

interviews where used to pull out as much

from the members involved where

possible. Some structured interviews were

conducted with the interviewee being

given the interview questions well in time

so as to source out the answers ahead of

the actual interview. The interviewees

included representatives from Botswana

Post (in terms of magazine licencing),

representative from Botswana National

Library (in terms of ISSN application), a

representative from the Department of

Information Services (for the historic

background), a representative from a local

publishing company, magazine editors,

magazine layout designers, and writers. In

some organisations, a mixture of semistructured and unstructured interviews was

conducted. This was due to the fact that

some information was kept in more than

one office due to unclear roles given out

and hence one person fails to answer the

questions and would therefore suggest

another person to be interviewed. This did

happen often due to the fact that most

ministries where re-structured over time

and are still doing so as issues arise.

There was a convenient focus group of

different individuals who were working to

put together a magazine (The Other

Kgotla) and they were very useful towards

the research. This group included fortyplus individuals who are connected or

Methodology of the Study

There are a number of research methods

used to tackle this broad topic.

Approach

The first approach was to use

descriptive research used to identify and

classify the elements and characteristic of

magazine production in Botswana. Mainly

quantitative techniques are used to collect,

analyse and summarise data. Qualitative

techniques were used to verify the data in

the form of interviews. Data triangulation the use of a variety of data sources to get

the same information was used to verify

collected information.

Secondary Data Collection

Most secondary data was sourced

through

background

reading

and

information gathering from books; articles

(academic journals, newspapers and

magazines); and pamphlets from different

organisations (government ministries,

Botswana Post, Information Services).

There was also an overall general search

over the Internet for available secondary

information.

10

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

interested in magazine production in

Botswana

thus;

magazine

editors,

designers,

writers,

photographers,

developers, event organisers, marketers,

promoters, to name but a few. Out of this

pool, most of the findings were verified to

see if they believe it is the case. This group

of individuals was also very helpful

whenever the research reached a dead end,

as they would suggest other avenues to get

the needed information.

In the end, all the information was

verified by following up with what is

happening at the actual magazine selling

outlets. An observation was made of as

many outlets as possible within Gaborone

(where most magazine in Botswana are

distributed) over a year and half. This

allowed a collection of most magazines

currently available in Botswana.

difference between a newspaper and a

magazine is. Therefore, one fills in the

given form to the best of their abilities of

which at times could be confusing even to

the administration personnel handling their

file. An observation was made to the fact

that even though these magazines where

wrongly classified, this was not the case

when it comes to the newsstands and

neither was it the case when it came to

which section they fall under at the

libraries- the said magazines would fall

under the magazine sections with a

disregard to the classification. Therefore,

such instances are corrected within this

research after undergoing a fact-finding

mission for each magazine which is

believed to be wrongfully classified.

From the many available types of

magazine circulation it was concluded that

in the case of Botswana, the types of

circulation include; paid circulation,

society/association

circulation

and

controlled circulation. As such in

Botswana, magazines are distributed

through supermarkets, filling stations,

newsstands (setup at mall corridors,

outside major stores, at the bus station), at

given events (the stadium or at malls),

other stores (e.g.: Pharmacies).

There are a number of challenges that

face the local magazine production

industry in Botswana, most of which is

common to the local print industry. Most

of the challenges are mainly to do with the

competitiveness of the industry and could

be overcome with good strategies. The

challenges, which were also discussed in

an article in The Patriot (Amogelang,

2013) include;

Findings

According to the Botswana Registry of

Companies Registrar of Companies and

Intellectual Property - Name Search

online database (Industry, 2012), there are

257 registered magazines in Botswana. It

is the authors observation that it is not

possible to find more than 10 locally

produced magazines on any given

newsstand at a given time within the

country.

Due to the lax methods of record

keeping and standards that govern

magazine registration and licencing in

Botswana, it is difficult to have the actual

statics about the current situation in

Botswanas magazine print industry. This

also goes for the growth of the industry.

It must be noted that due to

irregularities in classification, some

magazines in Botswana are classified as

newspapers. This happens at the point of

registration or at the licencing due to the

fact that the forms filled in do not indicate

clearly what the options are and what the

The lack of a readership

Most local magazine production

companies do not take time to understand

and build an audience for their produced

magazines. Instead, the lack of an audience

11

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

is blamed on the small population that

makes up the country. Most magazine

production companies however do not

conduct research on their audience leading

to them not knowing who their audience is

and therefore not meeting up to any

expectations.

years due to exposure to good quality

printing from competing magazines on the

newsstands.

Lack of appeal to advertisers

The targeted advertisers believe that

most magazines produced in Botswana are

of low quality as compared to their

counterpart from outside the country. That

being put aside, the fact that almost all

other media approach the same companies

for advertising opportunities; it is difficult

to settle with an advertisement space in a

magazine as compared to other, more

popular, media within the country such as

radio and television. If however a

company had an advertising budget for

print media, the company would rather

spend it on newspapers as this is more

popular than most magazines.

Lack of a market

This is the case as the population of the

country is small compared to most other

nations and added to this problem is the

fact that local magazines have to compete

with foreign produced magazines which

are also available on the newsstands. Most

of the foreign produced magazines that are

available in Botswana newsstands are from

South Africa. The opposite of having

Botswana produced magazines being

exported for sale in other countries such as

South Africa has been very difficult due to

the lack of appeal.

Lack of support at the distribution

points

In most scenarios, magazines are

distributed at supermarkets and/or petrol

filling stations. These avenues at times are

a franchise with the parent company being

based in South Africa. Thus these

distribution points inherit contracts from

the parent companies which allow them to

distribute most magazines which are

distributed at the parent company. Thus,

they reserve space for foreign produced

magazines on their newsstands that also

appeal to the local audience. This act at

times leaves little or no space for

Botswana produced magazines.

High local printing and publishing

costs

There are a few printing and publishing

houses in Botswana and thus the prices are

high due to a monopoly of the market. The

fact that the numbers being printed is also

not of a great volume adds to the fact that

the printing costs will remain considerably

high. To overcome this situation, some

magazine production companies have

resorted to print in South Africa- where it

is cheaper, and distribute in Botswanawhere the content is relevant.

Lack of good quality content

Some of the magazines suffer from a

lack of quality content in terms of well

researched and written articles, good

illustrations and graphics, and good

magazine layout and design. The

presentation of the content, starting with

the cover page, is an area that is lacking as

the readers have become spoilt over the

Lack of local celebrities

The last but not least challenge is the

fact that there are no local celebrities in

Botswana. The lack of such leads to a

failure to draw the attention of people

passing nearby and staring at a newsstand.

This is crucial as most times the audience

is bombarded with a lot of choices in terms

12

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

of magazines- both locally produced and

foreign magazines. Being able to identify

something or someone familiar could be

the difference between picking and not

picking a magazine from a newsstand. But

it is said that the media has the power to

make a celebrity, thus they could create

some local celebrity so as to overcome this

issue.

Another way to overcome this issue and

others at the same time would be by the

use of media conglomerates to assist in a

production of a magazine and other

associated services. By forming media

conglomerates, magazines would benefit

from corporate strengthening and

sharing of overheads (Click and Baird,

1983).

Advertising in the local magazine still

remains the best way to recover the

production costs. It is however very

difficult for magazines to secure

advertisement for their publications as they

are competing with other media such as

radio, television and worse of all

newspaper. This is the case for the

magazine industry throughout the world

however, it makes it more challenging in

the case of Botswana produced magazine

as the producers are unable to back up

their marketing with statistics from

independently conducted research.

There is a need for the nation to

conduct periodic and independent research

on the media such as the ones performed

by the Audit Bureau of Circulation in other

countries. The research findings are of

benefits to the local print magazine, its

investors and to the audience at large.

According to Sechele (2006), There is a

need to step up audience and readership

research capacity in Botswana.

Discussion

Lack of easy access to information from

key offices has led to a lot of difficulty in

getting information, which thus led to

more time in completing the research. The

researched information is of benefit to all

and hence should be included in local

reports on media. In most cases, statistics

in terms of magazine production is covered

under one umbrella as print media or as

newspapers. This then leads to a lack of

statistics in terms of the magazine

industry.

In terms of the editorial, most consumer

magazines in Botswana suffer from a lack

of well researched and well written content

for the target audience. This is caused by a

lack of planning when putting together an

editorial team at the beginning or the

choice of wrong team members. This

shows a lack of a magazine strategy. With

the strategy document at hand, a lot of the

failure points discussed on this paper

would be avoided.

The circulation of magazines in

Botswana is usually done by the same

company, which produced the magazine.

This is an extra cost that is usually not

factored into the calculations when setting

up a magazine. The lack of a door-to-door

delivery service by the Botswana Post

could have aided the industry as this could

have assisted in distribution through

subscription. Other third party distribution

methods remain available but are still too

expensive to be a viable option for now.

Conclusion

There are no measures to audit the

magazines produced in Botswana. Such

offices as the Audit Bureau of Circulation

do not exist in the country and such a role

is meant for the Botswana Post to cover.

Thus, there are no statistical figures (such

as the ABC figures) about any of the

magazines produced within the country. At

times the Audit Bureau of Circulation

South Africa does capture some

information on Botswanas circulation but

13

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

this is on average and does not reflect the

magazine industry in Botswana. Research

such as the National Readership Surveys

and the Quality of Reading Survey should

be conducted within Botswana.

The future of the magazine industry in

Botswana seems bleak. However, Click

and Baird (1983) says, Mans need for

knowledge, entertainment and ideas assure

the magazine industry of survival,

probably in a greater variety of formats

and forms than now exist. If this is

anything to go by, there is still hope for the

industry within the country.

The research was biased to traditional

printed magazines, as this is the

dominating type available at the time of

research. However, areas for future

research include a look into digital

magazines, as this is slowly becoming a

common trend. Added to this, other areas

of future research would be to narrow in

on different key areas such as; advertising,

advertorial, and circulation, so as to have a

deeper understanding of the industry.

communication in contexts. New York :

Routledge.

Evans, M. R. (2004) The layers of

magazine editing. New York: Columbia

University Press.

Hurman, J. (2013) Magazines may be

working. But magazine advertising isn't.

New Zealand: Tangible Media Ltd.

Industry, M. O. T. A. (2012) Registrar

of Companies and Intelectual Property Name Search [Online]. Gaborone: ROCIP.

Available:

http://www.mtinamesearch.gov.bw/search/

[Accessed 20/09/2013 2013].

Katz, H. E. (2003) The media

handbook: a complete guide to advertising

media selection, planning, research, and

buying. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum,

2nd ed.

Kobak, J. B. (2002) How to start a

magazine. New York : M. Evans and Co.,

2002.

McKay, J. (2006) The magazines

handbook. London: Routledge, 2006. 2nd

ed.

O'Connor, K. (2013) Media: As

magazines evolve, so should the metrics

used

to

gauge

their

success.

http://ehis.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid

=2&sid=78ded944-a5c1-4fe9-8e5183b0a76fe527%40sessionmgr114&hid=10

2&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%

3d%3d#db=bth&AN=89891899

[Accessed 12/11/2013].

Rinallo, D. and Basuroy, S. (2009)

Does Advertising Spending Influence

Media Coverage of the Advertiser?.

Journal of Marketing, 73: 33-46.

Rosengren, S. and Dahln, M. (2013)

Judging a Magazine by Its Advertising:

Exploring the Effects of Advertising

Content on Perceptions of a Media

Vehicle. Journal of Advertising Research,

53: 61-70.

References

Amogelang, E. (2013) Botswana

Magazine Publishers Struggling to Make

Headway. The Patriot.

Angus Stevenson, C. A. L. (2005) New

Oxford American Dictionary. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Botswana, Government of (1999)

Botswana

Handbook.

Government

Printers.

Click, J. W. & Baird, R. N. (1983)

Magazine editing and production.

Dubuque, Iowa: W. C. Brown, 1983. 3rd

ed.

De Beer, A. S. (1998) Mass media,

towards the millennium : the South African

Handbook of mass communication,

Pretoria: J.L. van Schaik, 1998. 2nd ed.

Duffy, B. E. and Turow, J. (2009) Key

readings in media today : mass

14

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

Sechele, S. T. (2006) Botswana:

Research Findings and Conclusions.

London: BBC World Service Trust.

Williams, T. A. (2004). Publish Your

Own Magazine, Guidebook, or Weekly

Newspaper: How to start, manage, and

profit from your own homebased

publishing company, USA, Sentient

Publications.

About the Author

Martha Mosha is a lecturer at the Media Studies Department, Faculty of Humanities,

University of Botswana. She holds a Masters degree in Design Science (Digital Media) from

the University of Sydney (Australia). Digital media includes area such as video production,

compositing, graphics design, animation and sound design for visual media. A first degree

from the University of Botswana- Bachelor of Design (D&T Education) enables her to be a

teaching instructor. Her experience is in the following areas; graphics design, digital video

production, project management and training within the area of media production. Her

interests are mainly in digital postproduction. Email: martha.mosha@mopipi.ub.bw

Suggested citation

Mosha, M. (2014) The Local Print Magazine Industry in Botswana. In Rooney, R. ed. The

Botswana Media Studies Papers. Gaborone, Department of Media Studies, University of

Botswana.

15

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

Corporate Social Responsibility and

Community Development in Botswana:

An Analysis of the Perspectives of the

Beneficiaries

Divya Nair

Abstract

The paper aims at understanding the relationship between corporate social responsibility

(CSR) and community development in Botswana. In the extant literature there is very little

discussion on the impact of CSR on stakeholders, particularly in the context of Botswana.

The literature shows that there is a need to develop a proper conceptual framework that

would make the risks and benefits tangible and visible to the various stakeholders. The

concept of CSR has developed enormously since its inception half a century ago and

encompasses philanthropy, community development and legal and ethical issues besides

economic responsibilities. But economic responsibilities of businesses are considered to be

dominant in the African context. This study based on fieldwork in Botswana analyses the role

played by grant managing institutions in delivering CSR and the perspectives of the

beneficiaries in this respect. The study highlights the various challenges posed by the

inadequate capacity of the grant managing institutions and the poor networking among the

various nongovernmental organizations. Hence it leaves a negative impression about CSR on

beneficiaries. A majority of the respondents believes that businesses engage in CSR for

reputation management and that they are the least concerned to facilitate local economic

development. Three quarters of the beneficiaries strongly feel that CSR should aim at funding

towards sustainable income generating programmes besides other areas. The Botswana case

necessitates the development of strong networks between the fund granting institutions, fund

managing institutions and the beneficiaries.

Key words: beneficiaries, Botswana, corporate social responsibility, perspectives,

stakeholders

The extant literature is focused largely on

the supply side. The origin of the concept

of social responsibility, the different

objectives adopted by firms in discharging

social responsibility and the types and

Introduction

Corporate Social Responsibility is a much

debated concept which evolved through

half a decade acquiring different

connotations at different points in time.

16

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

structure of delivery have also attracted

considerable scholarly attention. Similarly

much of the discussion has been centered

on North America and Western Europe.

But a perusal of the literature clearly

shows two things. First, there is very little

discussion of the impact of social

responsibility on stakeholders, particularly

in the context of community development.

Secondly and more importantly, African

economies rarely figure in these

discussions. The objective of this paper is

to focus on the perspectives of the

stakeholders who benefit from the socially

responsible project of firms and enterprises

in Botswana, a middle income land locked

Southern African nation.

The reminder of the paper is organized

as follows: We start with a brief literature

review of the participation of businesses in

community development projects with

varying objectives. It is followed by a brief

discussion of the economy of Botswana

and the nature of socially responsible

spending of businesses. In the next section,

we briefly outline the methodology of our

study which is followed by a discussion of

the perspectives of beneficiaries of CSR in

local

community

development

in

Botswana. In the concluding section the

major findings are reported.

corporate philanthropy and organizational

citizenship (de Bakker et al., 2005). A

third view concerns modeling and

measurement of social responsibility in

terms of performance (Matten, et al.,

2003).

The first

view regarding the

expectations of the stakeholders from

businesses is intimately related to

community

development

and

the

perspectives of the beneficiaries regarding

the delivery of the CSR related to it. The

literature in this field describes several

major

goals

of

business

social

responsibility (Boehm, 2005). Among

these, a major stream of thought deals with

attempts of businesses to address social

problems and promote the welfare of the

community. Thus businesses sponsor

social welfare projects, make donations of

equipment, seek civic partnership I

projects and donate funds without being

tied to any specific projects (Boehm,

2005).

Sometimes

employees

of

businesses provide training and education

to the elderly and the youths (Googins,

2002). In recent years, there has been a

greater deepening of partnership between

business and community (Zadek, 2002).

Such participation sometimes involves the

risk of pursuing narrow interests by the

businesses leading to a negative

stakeholder perspective (Hamman, et al.,

2003). This necessitates the development

of a proper conceptual framework based

on transparency so that the benefits and

risks become tangible and visible to the

various stakeholders (Boehm, 2005).

These stakeholders often emerge around a

shared interest to cope with common

problems together and solve them (Hess et.

al., 2002). Of late, one finds an increasing

role of the civil society in local

development issues on the support of

businesses (Baker, 2002). Authors like

Porter go even to the extent of arguing that

Overview of Literature

Academic discussion on the social

responsibilities of business firms started at

least half a century ago. It encompasses the

economic, legal and ethical expectations of

society from businesses (Carroll, 1979). A

very detailed and critical review of the

evolution of the concept with its varied

dimensions is available in de Bakker et al.

(2005). Whetten et al. (2002) view CSR as

expectations of the stakeholders from

businesses. Another view considers CSR

as an empirical concept that relates to

business ethics, sustainable development,

17

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

firms should establish clear linkages with

the community in which they operate to

gain competitive advantages as well

(Porter,1995). But he is quick to point out

that such goals can lead the community to

not only prosperity, but also to failure

(Porter and Kramer, 2002). It is in this

context that the perspectives of the

beneficiaries assume importance. The

success or failure of community

development programmes initiated by

business enterprises depends not only on

the self assessment of the enterprises

themselves, but also more crucially on the

opinions and attitudes of the beneficiaries.

Studies relating to this aspect of CSR are

generally rare. The modest objective of

the present paper is to fill this gap to a

limited extend using a case study of

beneficiary perspectives in Botswana.

CSR as a concept and practice was born

in the industrialized West and nurtured

also there. Some of the emerging

developing countries are fast catching up

with CSR. But, one finds only a few

efforts in African continent in this

direction. The available few studies are in

the context of South Africa. The available

limited literature indicates that the

economic responsibilities are found to be a

more serious concern of businesses than

philanthropy or legal or environmental or

ethical considerations (Eweje, 2006;

Phillips, 2006; Amaeshi et al., 2006; and

Hamann, 2004). The only study that was

found focusing on Botswana was

Lindgreen, et al. (2009). This study

highlights that the corporate decision

makers in Botswana are reluctant to

engage with wider CSR activities such as

philanthropy and positive environmental

practices as they are not convinced of clear

positive benefits from those. A study of

the perspectives of the stakeholders will

nevertheless be of greater interest

particularly in the context of the non-

altruistic and to some extent pessimistic

views of the businesses in Botswana.

Economy of Botswana

Botswana, a land locked country in

Southern Africa, is one of the most well

governed countries in Africa with a stable

democracy and prudent fiscal management

(Acemoglu et al., 2003; Curry, Jr., 1987).

It has recorded a sustained long term

growth rate of nearly 7 percent per annum

over a fairly long period of time. In recent

years, the annual compound growth rate

has decelerated to less than 5 percent. The

structure of the economy is dominated by

incomes from minerals and related

activities accounting for about 32 percent

of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The

next largest contributor to GDP is the

Government with a share of 18 percent

followed by financial and business

services (13 percent) and trade and

commerce (11 percent). The tiny

manufacturing sector contributes only 4

percent to GDP. The population of the

country is a little above 2 million. Except

the state dominated mining and meat

producing industries, most of the

enterprises are small in size without

showing any significant signs of economic

diversification. Though Botswana is a

middle income developing country, the

poverty rate and unemployment rate in the

country are 23 percent and 24 percent

respectively. The corporate culture is

relatively new in the country and hence

CSR is still in its inception.

The business enterprises in Botswana

seek to align its CSR practices with the

Millennium Development Goals and

Vision 2016 of the country. The key areas

that CSR endeavours to reach out are

poverty, education, gender equality, child

and

maternal

health,

HIV/AIDS,

environmental sustainability and global

partnerships. Partnering with local

18

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

communities with respect to the above has

been the goal of some of the enterprises.

institution to institution which depend on a

number of factors such as the reputation of

the institutions, their size, coverage of area

of operations, capacity to handle specific

amounts of funding, project management

capacity and more importantly fund raising

capacity.

The funds received were for the

following purposes: buying uniforms,

books, writing materials, mid-day meals

etc. for children in primary and secondary

schools, educational scholarships for

students at tertiary educational institutions,

infrastructural development, counseling

HIV/AIDs patients, creating jobs for the

poor, providing support to destitute

children and the aged.

These institutions, however, do not

have any scientific method to identify the

potential beneficiaries, as the use of such

methods is far too expensive. Hence they

rely mostly on media, opinion makers in

the community, civil society organizations

and faith based institutions such as

churches and other religious organizations.

The major challenges faced by these

institutions whose activities play a key role

in opinion making among the beneficiaries

have been identified are as follows:

Inadequate capacity of the institutions.

Most organizations have problems in

managing the resources and also for

accounting for the used funds due to lack

of skilled personnel and also due to lack of

adequate commitment. This often gives

room to the beneficiaries for construing the

intentions of the institutions as malafide.

Furthermore, some of the institutions do

not submit an evaluation report to the

funding organizations and hence there is

no way to gauge precisely the impact of

funding on the targeted community.

Another challenge is lack of networking

among the various non-governmental

organizations who are involved in using

the funds provided by businesses towards

Methodology

The study is based on primary data

collected using structured questionnaires

and focus group interviews / discussions

carried out in 2009. Data collection was

confined to Gaborone, the capital city of

Botswana and Mochudi, one of the largest

villages on the outskirts of Gaborone. A

two stage sampling procedure was adopted

to collect the necessary data concerning

the perspectives of the beneficiaries and

stakeholders. The first stage is constituted

by

the

major

grant

managing

institutions/voluntary organizations in the

country such as Stepping Stones,

University of Botswana, SOS Childrens

Village, F.G. Mogae Scholarship Fund,

Somarelang Tikologo, The Backyard

Garden Initiative, and Charity Begins at

Work.

The next stage consists of

individual beneficiaries. A list of

beneficiaries was collected from the above

mentioned grand managing institutions

and 25 percent of the beneficiaries that

work out to 94 were selected at random for

data collection. The beneficiaries consisted

mainly of orphans and other vulnerable

students, University graduates, University

students, primary and secondary school

students, and HIV patients. The 94

respondents were selected on the basis of

their proportion in the population of the

study. Separate questionnaires were

administered

for

grant

managing

institutions and beneficiaries as the role of

these actors are different in the execution

of CSR.

Discussion

All the grant managing

regularly receive funds from

and corporate institutions,

quantum of funds received

institutions

commercial

though the

vary from

19

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

fulfilling their CSR. As the funds provided

for community development activities are

often inadequate and available in small

amounts, the lack of coordination and

networking among the institutions end up

in making sharing of best corporate social

responsibility practices difficult. Similarly,

each organization uses parts of the funds

that are directed towards the same kind of

community development tasks, for

financing their own infrastructural

developments and recurring expenditure.

This results in a thin spread of the scarce

resources across various organizations for

more or less similar tasks which could

have been avoided, had there been proper

networking and coordination among the

NGOs. Consequently the resources that

really reach the beneficiaries get

considerably reduced leaving the task at

hand unfinished and leaving a negative

impression on the beneficiaries.

Thus not only the CSR practices of the

businesses, but also the nature of

functioning of the grant-using institutions

play a role in shaping the perspectives of

the beneficiaries. At the end of the day, the

ultimate effectiveness of CSR is

determined by the perspectives of the

beneficiaries.

Of the 94 respondents, 77 percent were

of the opinion that they are not satisfied

with the quantity and quality of the

community

development

activities

undertaken by the businesses. The

question on why the businesses engage in

CSR has elicited the following responses

from the beneficiaries on a five point scale.

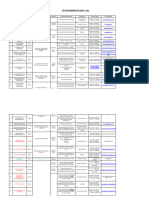

Table 1: Beneficiary Response to CSR Motivations

Reason

Plough-back to

communities

For

Competitive

advantage in

the market

For Social

Change

Reputation

Damage

Control

Local

Economic

Development

1

38

(40.4)

34

(36.2)

2

55

(58.5)

43

(45.7)

42

(44.7)

73

(77.7)

33

(35.1)

5

1

(1.1)

9

(9.6)

Total

94

8

(8.5)

41

(43.6)

19

(20.2)

11

(11.7)

-

94

2

(2.1)

94

25

(26.6)

15

(16.0)

15

(16.0)

6

(6.4)

94

94

Note: Figures in brackets indicate percentages.

Column headings in the table from 1 to

5 indicate various levels of agreement with

1 has the highest value and 5 the lowest

value. From the table it appears that the

impression of the beneficiaries is that the

businesses resort to CSR largely for the

damage control of their reputation in the

community. 78 percent of the beneficiaries

strongly agree to this. Next to this is the

impression that businesses spend money

for social change in the community. This

opinion is given strong support by 45

percent of the respondents. This is closely

followed by the perspective (40.4) that

businesses care to plough back some

amount of the money that they earn from

the society through CSR. More than a third

of the respondents have the impression that

20

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

CSR is practiced mainly for the

competitive advantage of the enterprises.

Roughly one third of the opinion is that

local economic development is a strong

motive behind CSR. A concise measure of

the perspectives of the beneficiaries can be

obtained, if a principal component analysis

is carried out. This will help us to

determine the extent to which the different

variables that are related can be grouped

together so that they can be treated as one

combined variable or factor rather than a

series of separate variables. The next step

in this study will be the estimation of the

varimax

factors

that

substantially

determine the total variance.

The beneficiaries also suggested ways

in which the real delivery of CSR could be

effective. Table 2 gives the opinions of the

beneficiaries on a five point scale as in the

case of Table 1.

Table 2: Areas for Improvement According to Beneficiaries

Areas for

Improvement

Coordinated

CSR activities

Consultative

need

Assessment

with

Implementers

More Support

Towards Long

Term

Programmes

Mainstreaming

of CSR in

Sponsors

Corporate

Strategy

Forging

International

Linkage

Funding

Towards

Sustainable

Income

Generating

Programmes

No Opinion

12

(12.8)

10

(10.6)

25

(26.6)

15

(16)

57

(60.6)

69

(73.4)

43

(45.7)

25

(26.6)

5

(5.3)

21

(22.3)

8

(8.5)

14

(14.9)

72

(76.6)

15

(16)

79

(84)

78

(83)

16

(17)

Note: Figures in the brackets indicate percentage to total

The chief need of the beneficiaries as it

appears from table 2 is CSR directed

towards income generating activities. The

beneficiaries also want these activities to

be on a long term basis implying that short

term support will not have a sustained

impact on the beneficiaries. The other

areas of improvement shown in the table

seem to be beyond the comprehension of a

majority of beneficiaries. These results

corroborate the finding of the Lindgreen et

al. (2009) study which states that rather

than philanthropy, the major theme of the

responses from Botswana managers was

21

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

the importance of the economic role of

business. A principal component analysis

is likely to come up with a clearer

understanding

of

suggestions

by

beneficiaries of the areas of improvement.

Amaeshi, K.B., C., Ogbechie, A. C.,

and Amao, O. (2006) Corporate Social

Responsibility in Nigeria: Western

Mimicry or Indigenous Influences,

Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 24:8399.

Baker, G. (2002) Civil Society and

Democratic Theory: Alternative Voices,

New York: Routledge.

Boehm, A. (2005) The Participation of

Business

in

Community

Decision

Making, Business & Society, 44:144-177.

Carroll, A. B. (1979) A Three

Dimensional Conceptual Model of

Corporate Social Performance, Academy

of Management Review, 4:497-505.

Curry, Jr. R. L. (1987) Botswanas

Macroeconomic Management of Its

Mineral-Based Growth, American Journal

of Economics and Sociology, 46:473-488.

De Bakker, F., Groenewegen, P., and

Hond, F. (2005) A Bibliometric Analysis

of 30 years of Research and Theory on

Corporate Social Responsibility and

Corporate Social Performance, Business

& Society, 44:283-317.

Eweje, G. (2006) The Role of MNEs in

Community Development Initiatives in

Developing Countries: Corporate Social

Responsibility at work in Nigeria and

South Africa, Business and Society,

45:93-129.

Googins, B. (2002) The Journey

Towards Corporate Citizenship in the

United States, Journal of Corporate

Citizenship, 5:85-101.

Hamann, R. (2004) Corporate Social

Responsibility,

Partnerships,

and

Institutional change: The Case of Mining

Companies in South Africa, Natural

Resources Forum, 28:278-290.

Hamman, R., Acutt, N. and Kapeluse,

P.

(2003)

Responsibility

versus

Accountability? Integrating the World

Summit on Sustainable Development for a

Synthesis

Model

of

Corporate

Conclusion

The present study made an attempt to

analyse the role grant managing

institutions play in delivering CSR and to

measure the perspectives of the

beneficiaries with respect to CSR. It has

been pointed out that Botswana is a

country characterised by low levels of

industrialization and hence low intensity of

CSR practices by firms. The NGOs that

act as the intermediaries between the

actual beneficiaries and the businesses are

often inexperienced and do not possess

adequate skills or capacity to deliver the

goods. The beneficiaries though have a

perspective that is positive on the CSR of

firms, still nurture a predominantly

negative impression about the motive of

CSR. A clear reading of these indicates

that there is a lack of coordination and

networking between the fund granting

businesses, fund managing institutions and

the beneficiaries. A fuller appreciation of

CSR in the Botswana context is made

possible only by developing strong

networks between these three actors. The

literature in the area of CSR is not very

eloquent on this aspect. Hence the major,

though modest contribution of this study

is the realization that further studies on

these lines are required to have a fuller

understanding of the impact of CSR.

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S. and

Robinson, J. (2003) An African Success

Story: Botswana. In Rodrik, D. Ed. In

Search of Prosperity: Analytic Narratives

in Economic Growth, Princeton: Princeton

University Press.

22

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

Citizenship, Journal of Corporate

Citizenship, 9:32-48.

Hess, D., Rogovsky, N. and Dunfee, T.

W. (2002) The Next Wave of Corporate

Community

Involvement:

Corporate

Social Initiatives, California Management

Review, 44:110-125.

Lindgreen, A., Swaen, V. and

Campbell, T.T. (2009) Corporate Social

Responsibility Practices in Developing and

Transitional Countries: Botswana and

Malawi, Journal of Business Ethics,

90:429-440.

Matten , D., Crane A. and Chapple, W.

(2003) Behind the Mask: Revealing the

True Face of Corporate Citizenship,

Journal of Business Ethics, 45 (1-2):109120.

Phillips, F. (2006) Corporate Social

Responsibility in African Context,

Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 24:2327.

Porter, M. E. (1995) The Competitive

advantage of the Inner City, Harvard

Business Review, 73:55-71.

Porter, M. E. and Kramer, M. R. (2002)

The Competitive Advantage of Corporate

Philanthropy, Harvard Business Review,

80: 56-68.

Whetten, D. A., Rands, G. and

Godfrey, P. (2002) What are the

Responsibilities of Business to Society?

Iin Pettigrew, A., Thomas, H., and R.

Whittington, R, eds. Handbook of Strategy

and Management, London: Sage.

Zadek, S. (2002) Partnership Alchemy:

Engagement, Innovation and Governance.

In Andriof, J. And McIntosh, M. Eds.

Perspectives of Corporate Citizenship,

London: Greenleaf.

About the author

Divya Nair holds a Masters degree in Communications from the Bangalore University, India.

She has worked with the Limkokwing University of Creative Technology, Gaborone, and

currently the University of Botswana in Gaborone as a lecturer in the Department of Media

Studies. Her major area of research interest is the role of public relations in Corporate Social

Responsibility and economic development. E-mail: sdivyanair@gmail.com

Suggested citation

Nair, D. (2014) Corporate Social Responsibility and Community Development in Botswana:

An Analysis of the Perspectives of the Beneficiaries. In Rooney, R. ed. The Botswana Media

Studies Papers. Gaborone, Department of Media Studies, University of Botswana.

23

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

The juxtaposition between media

literacy and democracy

Penelope Kakhobwe

Abstract

This paper proposes that there is a correlation which exists when it comes to media literacy

democracy and development. The paper makes a case for media literacy for all and not just

high school children but all sectors of society through cooperation with various nongovernmental organisations in the field.

The paper starts off by tracing the history of Malawi under the rule of the dictatorship of

president, Hastings Kamuzu Banda and the various legal constraints that still exist in Malawi

despite being a democratic state and shows that it is the norm in African countries for media

personnel to suffer persecution for their views.

Key words: Malawi, media literacy, Habermas, public sphere

with democracy and the creation of a

public sphere.

When African countries democratized

they were more focused on educating

people on what democracy was but how

can you have democracy with an ignorant

public? We had gender activist taking their

agenda to the masses and advocating for

the rights of women of course in some

instance where this was not communicated

adequately most women thought that it

meant that they could talk back to their

husbands and refuse them sex and house

chores. This was what I would call

miscommunication on the part of gender

activists and some today are trying to right

this wrong.

We go to Malawi my country where it

was totally no press freedom. What is

press freedom? It means journalists must

Introduction

When African countries underwent the

second wave of democracy in the late

1990s, one area was ignored: that of

media literacy. The second wave of

democracy consisted of getting rid of

dictators such as Hastings Kamuzu Banda

in Malawi. The new political parties

decided to ignore public media literacy and

perpetuated the system of keeping the

masses ignorant of their performance. We

cannot blame them as they inherited the

British system of government where the

native was not part of the target audience

for media but was kept out of it due to

issues of literacy and ability to speak the

Queens language, English. But this is

2013, the dawn of a new era and we cannot

ignore the juxtaposition of media literacy

24

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

have the ability to report news that they

feel is newsworthy to his audience.

Since the late 1990s, many African

governments have adopted democracy as a

form of government. Democracy is a

system for arriving at collective decisions

through the participation of interested

parties (Keane, 1991:168). For democracy

to prevail in a country there is need for is a

place where people discuss matters of

public interest which Habermas has called

a public sphere (Eley, 1996:298; Curran,

2002:3). It provides an ordered structure

which allows for democratic discourse and

is there to provide a forum for information,

critical debate and scrutiny (Merrill et al,

2001: xxii). The public sphere works as a

model in setting up of an arena that is

inclusive of diverse critical views from a

wide range of people.

Press freedom is a prerequisite for the

media to perform the above functions.

Freedom of the press is an indispensable

element in democracy and the attainment

of truth (Lichtenberg, 1990:102). Press

freedom is simply the absence of any form

of pre-publication censorship or any

requirement for a license or permission to

publish (McQuail, 1992:36). It is the

freedom to cover and report whatever the

majority of people want to know (Weaver

in Ogbondah, 1994:12).

However, many African governments

despite having democratic systems of

government have not embraced the press

freedom concept. As such there is freedom

in principle through new laws but no

practice or respect for it (Nyamnjoh,

2005:70; Ogbondah, 2002:63). Most

African governments have failed to

liberalize press laws (Berger, 1999:16;

Ogbondah, 2002:55). This state of affairs

holds true for Malawi.

Media environment in Malawi

When Malawi adapted a democratic

system of government, in 1993 it was

assumed that press freedom would flourish

as one of the tenets of democracy is press

freedom (Norris and Inglehart, 2008:4).

The lack of respect for press freedom and

disdain for journalism can be traced back

to the rule of the first President, Ngwazi

Kamuzu Banda. Malawi was declared a

republic in 1966 after attaining self-rule

from British colonial rule in 1964 (Crosby,

1993:xxxiv). It became a one-party state in

1966 with multi-party politics banned for

more than thirty years. The government set

up the Censorship Board in 1968

(Chimombo and Chimombo, 1996:1;

Mapulanga, 2008:1). The Board monitored

all literary material including newspapers.

President Banda viewed all non-fiction

writing suspiciously, believing it to be a

disguise

for

free-lance

journalism

(Chimombo and Chimombo, 1996:182).

There was only one daily newspaper; The

Daily Times and its sister weekend

newspaper Malawi News. Both were

owned by Banda through his company

Blantyre Print and Packaging Company.

These newspapers carried very little by

way of reference to current events in

Malawi (Chimombo and Chimombo,

1996:25). Journalists under this regime

experienced harassment and detention;

methods which according to Ogbondah

(1994); Tettey (2001) and Nyamnjoh

(2005) are prevalent in Africa.

The new constitution in Malawi came

into effect after the first democratic

elections in 1992. Section 35 of the

Malawi constitution states that: every

person shall have the right to freedom of

expression while Section 36 recognizes

press freedom and states the press has the

right to report and publish freely, within

Malawi and abroad (Constitution of the

Republic of Malawi, 1994). However,

25

The Botswana Media Studies Papers

restrictive media laws still remain on the

books. Legislation such as the Official

Secrets and Emblems Act, 1913, the

Printed Publications Act, 1947 and the

Censorship and Control of Entertainments

Act, 1968 which restrict press freedom is

still part of media regulation in Malawi

(KAS, 2003:14). Norris and Inglehart

(2008:2) are of the view that such

restrictive media environments manipulate

public opinion. Democracy was adapted as

a concept without the mechanisms for fair

participation (Eribo and Jong-Ebot,

1997:xiii).

Censorship policies that impact

traditional media have not been formulated

in some countries for the Internet.

Traditional media especially radio and