Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Influence of Socio-Cultural Aspects of Ethnobotany On Tree Species Propagation in Home Gardens: A Case Study in Miwani Division, Kisumu County, Western Kenya

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Influence of Socio-Cultural Aspects of Ethnobotany On Tree Species Propagation in Home Gardens: A Case Study in Miwani Division, Kisumu County, Western Kenya

Copyright:

Available Formats

IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science (IOSR-JAVS)

e-ISSN: 2319-2380, p-ISSN: 2319-2372. Volume 8, Issue 3 Ver. II (Mar. 2015), PP 18-25

www.iosrjournals.org

The Influence of Socio-Cultural Aspects of Ethnobotany on Tree

Species Propagation in Home Gardens:

A Case Study in Miwani Division, Kisumu County, Western

Kenya

Andrew Owino Omam 1 and Musa Gweya Apudo 2

1

Kenya Forest Service, OlBolossat Forest Station, P.O. Box 289, OlKalou, Kenya.

School of Natural Resource and Environmental Management, University of Kabianga, P.O. Box 2030

20200, Kericho, Kenya

Abstract: This study was done to establish if the peoples choice of tree species propagated in their home

gardens is influenced by Ethnobotanical knowledge. It was carried out in Miwani Division in Kisumu County,

Western Kenya between January 2014 and April 2014. Structured questionnaires/schedules, key informant and

focused group interviews and secondary sources of data were used to collect the relevant data. The collected

data were analyzed using the SPSS version 17. The study provided data on different tree species propagated in

home gardens, their locations and also established values attached to them.Traditional knowledge systems

count when it comes to deciding on what species to plant and where to plant them. This especially applies to

indigenous species. It is apparent that planted species or species natured and the specific sites where they are

found in the farm are determined by the knowledge and experience with them - the knowledge that is derived

from ethnobotany of the local area. The sitting of planting of any species is also closely related to the purpose

for planting. Ethnobotanical knowledge can thus be used to predict the choice of tree species to be propagated

in home gardens in this community.We recommend that in agroforestry, species choice and planting site

consider both biophysical and appreciate socio-cultural values attached to the species, the latter being the

consideration of the influences that culture has on society and, which can, in part, determine the social

acceptability of agroforestry at the farmers level. There is need to further research and establish the basis for

the superstitious views on tree species not just in this community but also in other communities in Kenya.

Keywords: Ethnobotany; Home gardens; Community; Socio-culture; Luo.

I.

Introduction

Ethnobotany is the study of the relationship between plants and people. It is derived from two words,

Ethno, meaning the study of people and Botany, meaning the study of plants. Ethnobotany studies the

complex relationship between (uses of) plants and human cultures. The focus is on how plants have been or are

used, managed and perceived in human societies (Staff, 2007). The history of Ethnobotany goes back to the

beginning of civilization when people relied on plants for survival. It explores how plants are used for food,

shelter, medicine, clothing, hunting, magico-religious concepts, conservation techniques and general economic

and sociological importance of plants in different societies. It begun when man first out of necessity, classified

plants; those of little or no utility, those which were useful in many practical ways, those alleviating illness and

those that made him ill and killed him. To others were attached spiritual powers from supernatural sources

(Evans, 1994).

In Kenya the indigenous people have used traditional medicine which they got from trees and shrubs

growing around them. Besides, curing of sickness and disease was associated with supernatural powers which

were believed to be living among the people. Some of these powers were associated with trees, and the presence

of a tree in a particular site signified the presence of a spirit of some kind, or, it was believed the tree housed the

spirit (Odak, 1990). Different ethnic communities in Kenya have had their own ways of forest and tree

conservation. In some communities the groves and valleys are homes to the spirits, medicinal herbs and sacred

plants and also serve as water catchment sites. No one is allowed to cut down sacred trees, medicinal plants and

trees near homesteads, springs and along rivers (Chepkwony, 2014). Reports from some regions have indicated

destruction of some tree species because of peoples perception about them. A case in Casamance Senegal

where the forestry service encouraged planting of cashew nut, rural people burned the trees to evict the evil

spirits which these trees were believed to shelter (FAO, 1986).

Among the shona tribe of Zambia religious traditions prohibit them from cutting certain tree species

which are associated with guardian spirits of the land. While still in Zambia it is perceived that only God can

plant forest trees and thus planting of indigenous tree species is culturally discouraged. In Zambia planting trees

DOI: 10.9790/2380-08321825

www.iosrjournals.org

18 | Page

The Influence Of Socio-Cultural Aspects Of Ethnobotany On Tree Species Propagation

implies ownership of a resource e.g. the land on which it is planted and the women in the area are usually

recognized as users not owners of the resource (Warner, 1993).

In many rural areas, the local populations still depend on traditional ways of life and rely on wood

products for survival purposes. They know the usefulness of trees from previous generations.

The questions that are pertinent here include: What species of trees are planted and/or natured? What

particular human needs do they serve? Where are the trees planted? Or why are they planted in particular sites

and not in some other sites? Also relevant are questions such as: are the trees planted in fields or around

homesteads? Are they planted in blocks or are they dispersed? The enquirer may also want to know if people

prefer to plant certain tree species and are unwilling to plant others, or who cares for the trees after they have

been planted (FAO, 1986).

Agroforestry has to consider both biophysical and socio-cultural aspects of the practice, the latter being

the consideration of the influences that agroforestry has on society and culture, which can, in part, be

determined by its social acceptability at the farmers level, as farmers are considered to be the primary

beneficiaries of agroforestry practices. The social acceptability of agroforestry is influenced by heterogeneity in

village structure, land and tree tenure arrangements, division of gender roles, and local perceptions and attitudes

towards trees. Important socio-cultural factors to be considered in agroforestry include land tenure, labor

requirement, and marketing of products, local knowledge, local organization, cultural and eating habits, gender,

and well-being and age of landowners (Atangana et al. 2014).

Miwani division lies at the foot-hills of Nandi escarpment and is prone to flooding during the long rains

with a lot of alluvial soil being brought from the Nandi escarpments.

The Luos who are the dominant ethnic community living in the area harbour both Christian and

traditional beliefs. The community is known for its bold approach to tradition and customary beliefs. The

community attaches socio-cultural values and symbolisms to trees and such values influence the acceptability of

the trees. Propagation of certain tree species, for example, Terminalia mantaly (Figure 4) has faced serious

challenges in some parts of luo land where it has been held with suspicion. There are reasons for planting, not

planting and for planting specific tree species in specific sites on farms and in homesteads.

The context in which the term home garden is used here is as explained in Nair, 1993; Tropical

homegardens consist of an assemblage of plants, which may include trees, shrubs, vines, and herbaceous plants,

growing in or adjacent to a homestead or home compound. These gardens are planted and-maintained by

members of the household and their products are intended primarily for household consumption; the gardens

also have considerable ornamental value, and they provide shade to people and animals. It involves intimate

association of multipurpose trees and shrubs with annual and perennial crops and, invariably livestock within

and adjacent to the compounds of individual houses, with the whole crop-tree-animal unit being managed by

family labor. It was thus necessary to investigate if the peoples choice of tree species propagated or natured in

their home gardens is influenced by their experience with and knowledge about the plants. The study provides

data on different tree species propagated in home gardens, their locations, and establish values attached to them.

The findings could open debate on different approaches to improve tree cover in the county (Kisumu), given

that the county was recently ranked second last in tree cover in the country with 0.04% tree cover (Kenya Water

Towers Task Force, 2013). It is the objectives of this paper to:

1. Establish a list of tree species growing in home gardens for various purposes.

2. Establish the specific locations where the tree species are grown in the farms/homesteads.

3. Determine the socio economic and cultural values attached to the woody plants in home gardens.

4. Determine if ethno botanical knowledge can be used to predict the choice of tree species to be propagated in

home gardens.

II.

Materials And Method

The study area

The study was carried out in Miwani division of Muhoroni sub county, Kisumu county. It lies within

latitudes 0 00 and 0 21 south and between longitudes 34 45 and 32 21 East, and covers a total area of 225.7

km2, with a population of 69,683 persons (Nyando District Development Plan, 2009). The division is divided

into three administrative locations, and fourteen sub locations.

The population distribution by sub location is as shown in table 1.

Table 1: Population distribution in Miwani division.

Locations

N.E. Kano

DOI: 10.9790/2380-08321825

Sub locations

Kabar cental

Kabar east

Kabar west

Sidho east

Kamswar north

Wangaya II

www.iosrjournals.org

Population

3050

6217

4029

2864

2851

5490

19 | Page

The Influence Of Socio-Cultural Aspects Of Ethnobotany On Tree Species Propagation

Ombeyi

Ramula

Kango

Kore

Obumba

Irrigation scheme

Wangaya I

Kamswar south

Sidho east II

Nyangoma

6058

4583

6551

4691

4424

6174

6251

6450.

Source: Nyando District Development Plan (2009).

Study design and method.

The study adopted a survey exercise involving interviews and direct observations.

Field techniques

Simplified multistage cluster random sampling technique was adopted using proportional allocation of

samples. The target population involved adults both male and female heads of households from sub locations in

the locations and were chosen using stratified random sampling, with sub locations constituting sampling strata.

The survey was spread across the whole division cutting across the locations. From each of the sub

locations, ten households (irrespective of socio economic conditions) were selected at random for the

comprehensive study. Thus a total of 140 households were sampled. Before the household survey,

reconnaissance field visits were arranged within the sub locations with village elders, Assistant chiefs, Chiefs

and religious leaders, to get their opinion about the status of tree species propagation in the area, during which

time different tree species growing in the area was recorded.

Data collection methods

The following data collection methods were used:

Interviews

Informal meetings were held in the interviewees homes, conducting interviews in the local language.

The household heads were the key respondents, with the help of other family members when necessary. In

addition fourteen focus group discussions (FGD), one in each sub location, were arranged at the Assistant

chiefs office at every sub location. Information on the kind of trees which are planted and natured in the

homesteads, those tree species which are not recommended to grow in the homesteads, uses of trees and tree

products and reasons for planting trees and other cultural issues associated with tree planting were discussed.

The respondents were interviewed using semi structured questionnaires and focalized interviews to ascertain the

tree species growing or grown on the family land, specific sites where they are grown and the socio economic

and cultural values attached to them.

Data analysis and presentation

The data was analyzed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS). Presentation is in the

form of tables, graphs and charts as appropriate.

III.

Results

Table 2: The sex of household heads interviewed

Location

North East Kano

Ombeyi

Nyangoma

Total

DOI: 10.9790/2380-08321825

Sub location

Kabar central

Kabar East

Kabar West

Sidho East

Kamswar North

Wangaya II

Ramula

Kango

Kore

Obumba

irrigation scheme

Wangaya I

Kamswar south

Sidho east II

Female

2

4

3

2

5

3

2

3

3

4

3

3

4

3

44

31.4%

www.iosrjournals.org

Male

8

6

7

8

5

7

8

7

7

6

7

7

6

7

96

68.6%

Total

10

10

10

10

10

10

10

10

10

10

10

10

10

10

140

100%

20 | Page

The Influence Of Socio-Cultural Aspects Of Ethnobotany On Tree Species Propagation

Table 3: Tree species growing in home gardens and their reported use

S/NO

Botanical name

Common

name

Grevillea,

(Silky oak)

Local name

Method of

propagation

Artificial

Indigenous or

exotic

Exotic

(Naturalised)

Grevillea robusta

Markhamia lutea

Markhamia

Siala

Natural &

artificial

Indigenous

3

4

Terminalia mantaly

Mangifera indica

Terminalia

Mango

Umbrella tree

Maembe

Thevetia peruviana

Thevetia

Chamama

Exotic

Exotic

(Naturalised)

Exotic

Croton

megalocarpus

Croton

Tindri

Artificial

Artificial &

natural

Natural &

artificial

Natural and

artificial

Cassia

Obino

East African

Green heart

Grewia

Abaki

Natural &

artificial

Artificial

Exotic

(Naturalized)

Indigenous

Senna siamea

(Cassia siamea)

Warburgia

ugadensis

Grewia bicolor

Powo

Natural

Indigenous

10

Balanites aegyptiaca

Desert date

Othoo

Natural

Indigenous

11

Sesbania sesban

Asao (Osao)

Natural

Indigenous

12

Euphorbia tirucali

Ojuok

Artificial

Indigenous

13

Madat

Natural

Indigenous

Giant

diospyros

Albizia

Ochol

Natural

Indigenous

15

Teclea nobilis

(Vebris nobilis)

Diospyros

abyssinica

Albizia coriaria

Sesbania

(River bean)

Finger

euphorbia,

milk bush.

Teclea

Ober

Natural

Indigenous

15

Ficus capense

Ficus

Ngou

Natural

Indigenous

16

Tamarindus indica

Tamarind

Ochwa(chwaa)

Natural

Indigenous

17

Terminalia brownie

Manera

Natural

Indigenous

18

Terminalia catapa

Artificial

Exotic

19

Eucalyptus

citriodora

Eucalyptus

camaldulensis

Eucalyptus saligna

Red pod

terminalia

Indian almond,

Bastard

almond

Lemon-scented

gum

Blue gum

Ndege

Artificial

Exotic

Mti mbao (bao)

Artificial

Exotic

Nyar maragoli

Artificial

Exotic

Liyo

Artificial

Exotic

Dwele

Artificial

Indigenous

14

20

21

Rais

Indigenous

22

Casuarina

equisetifolia

23

Melia azadaracht

Sydney blue

gum

Whistling pine,

Swamp she

oak

Persian lilac

24

Azadirachta indica

Neem

Muarobaine

Artificial

Exotic

25

Euphorbia

candelabrum

Bondo

Natural

Indigenous

26

Kigelia Africana

Tree

euphorbia,

Candelabra

euphorbia

Sausage tree

Yago

Natural

Indigenous

27

28

Ficus capense

Erythrina tomentosa

Fig tree

Flame tree,

Ngou

Orembe

Natural

Natural

Indigenous

Indigenous

29

Acacia gerrardii

Gerrard's

acacia

Sae

Natural

Indigenous

30

Acacia polyacantha

Falcon's claw

acacia

Ogongo

Natural

Indigenous

DOI: 10.9790/2380-08321825

www.iosrjournals.org

Reported use.

Agroforestry, timber

&

Boundary mark.

Agroforestry,

timber, poles &

shade.

Shade, ornamental.

Fruit, charcoal &

shade

Live fence,

ornamental.

Shade, charcoal,

windbreak, fuel

wood, tool handles.

Poles, fuel wood,

windbreak, shade.

Medicinal &

ornamental

Medicinal, fodder &

shade

Shade, medicinal &

charcoal

Agroforestry &

fodder

Fencing & fuel

wood

Shade, walking

sticks, tool handles

Shade, medicine,

tool handles

Shade, timber,

charcoal (woodfuel)

Conservation of

water catchment,

oxen yoke

Fruits, fire wood &

charcoal & shade

Poles, shade, wind

break

Ornamental, fruit

Timber, posts, poles,

medicine

Timber, poles, posts,

charcoal

Timber, poles, posts,

charcoal

Ornamental, poles,

fuel wood, boundary

mark,

Medicinal,

ornamental

Medicinal, shade,

ornamental

Used to perform

cultural rituals

Used in performing

cultural rituals

Making oxen yoke

Used in performing

cultural rituals

Shade, charcoal

Timber, shade &

wind break

21 | Page

The Influence Of Socio-Cultural Aspects Of Ethnobotany On Tree Species Propagation

31

32

33

34

35

Calliandra

calothyrsus

Leucaena

leucocephala

Lannea

schweinfurthii

Moringa oleifera

Ficus benjamina

Caliandra

Caliandra

Artificial

Exotic

Leucaena

Leucaena

Artificial

Exotic

Lannea

Kwogo

Natural

Indigenous

Drumstick tree

Ficus

Moringa

Ficus

Artificial

Artificial

Indigenous

Exotic

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Fodder, agroforestry

& fire wood

Fodder & fire wood

Fuel wood,

medicinal

Food & medicine

Shade & ornamental

Natural

regeneration

Artificial

propagation

Artificial & natural

regeneration

N.E Kano

Ombeyi

Nyangoma

Total

Figure 1: Propagation methods by sub locations

Figure 2: Category of nursery depended upon (Sources of Seedlings for propagation)

Figure 3: Purpose of planting within homestead

DOI: 10.9790/2380-08321825

Purpose for tree propagation outside the homesteads

www.iosrjournals.org

22 | Page

The Influence Of Socio-Cultural Aspects Of Ethnobotany On Tree Species Propagation

Figure 4: Some tree species which the community has strong reservations against

Table 7: Specific tree species and preferred planting sites

Preferred site

Anywhere in

the home

garden

140

Those who do

not know the

tree

0

Purpose for

propagation

94

26

46

18

26

87

65

70

10

-

18

48

7

27

28

65

87

-

Yago

121

19

Erythrina tomentosa

Orembe

127

13

Ficus capensis

Croton megalocarpus

Ngowo/Ngou

Tindri

0

16

123

102

17

22

0

0

Melia azadaracht

Euphorbia

candelabrum

Tamarindus indica

Teclea nobilis

Euphorbia tirucali

Grewia bicolor

Dwele

Bondo

41

0

46

131

53

9

0

0

Ornamental & shade

Fodder, shade, & poles

Shade, charcoal

Shade, charcoal,

fencing

Beauty, shade

Shade, beauty, timber,

charcoal

Traditional medicine,

cultural rituals

Traditional medicine,

oath taking. Treatment

of mumps culturally.

Shade, charcoal,

aesthetics

Herbal medicine

-

Ochwa (chwaa)

Madat

Ojwok

Powo

17

84

95

43

61

45

0

8

62

11

55

89

0

0

0

-

Warburgia ugandensis

Thevetia peruviana

Casuarina equisetifolia

Abaki

Chamama

Liyo

34

103

21

9

1

5

97

26

114

0

0

Moringa oleifera

Moringa

126

Species botanical

name

Local name

Within

homestead

Markhamia lutea

Siala

Terminalia mentalis

Terminalia brownie

Balanites aegyptiaca

Acacia gerrardii

Umbrella tree

Manera

Othoo

Sae

10

27

29

52

Terminalia catapa

Albizia coriaria

Ober

Kigelia Africana

Outside the

homestead

IV.

Timber, building

materials

Fruits, shade

Walking sticks

Fencing

Basket weaving

materials Fodder

Medicine, ornamental

Fencing

Beauty, shade, wind

break

Food, herbal medicine

Discussion

About 69% of respondents were male while about 31% were female (Table 2). This is important

because this is one of the communities in which tree planting and ownership is mainly a males affair.

Culturally, the only activities women are allowed to do in tree growing without asking for consent from men are

watering and weeding. All other activities required in tree growing are a preserve of men (Oloo, 2013). Where

DOI: 10.9790/2380-08321825

www.iosrjournals.org

23 | Page

The Influence Of Socio-Cultural Aspects Of Ethnobotany On Tree Species Propagation

female respondents were used as household heads the female was either widowed or the male household head

was away. This has more to do with cultural dimensions on land and tree tenure. Planting trees would amount to

assertion of ownership of the land on which the tree is grown, yet women, in this community, do not own land.

It is appreciated, however, that tree uses are well known by both males and females alike. Elderly people, male

or female, are much informed about medicinal and other special values and uses of the various plants. Therefore

the purposes for tree planting and decisions on planting sites are likely to be known both to males and females

alike. What is likely to differ is prioritization of what specific species to plant. These findings concur with those

of Oloo (2013) in the neighbouring Siaya County in which according to the Luo Council of Elders it is a taboo

in the society for women to grow Euphorbia triculli, Agave sisalana, Albizia coriaria, and Tamarindus indica.

Euphorbia triculli and Agave sisalana are used as land boundary markers and it would only be land owners,

which in this community are men, who can plant them.

Tree species growing in home gardens for various purposes

Thirty five (35) species of trees were recorded to be growing on the farmlands. Twenty one (21) were

indigenous and fourteen (14) exotic (Table 3). Most (> 70%) of the indigenous species regenerated naturally and

only six (< 30%) were artificially propagated. Those that were artificially propagated included the very highly

valued medicinal species such as Warburgia ugandensis, Melia azadaracht and Moringa oleifera and valuable

and respected fencing species such as Euphorbia tirucali. It is a curse in this community to uproot, in a bid to

interfere with the boundary, Euphorbia tirucali that mark property boundary between neighbours. This sociocultural value, meant to enhance respect and harmonious coexistence between neighbours, gives this species a

special and definite physical niche within the farming landscape. Markhamia lutea is among the indigenous

species that will be artificially propagated because of its value in traditional house construction, furniture

materials and its relative fast growth. Over 71% of indigenous species were recorded to be regenerating

naturally in the study area. There could be a number of reasons for this. Many indigenous trees are associated

with the presence of spirits, some of which are not friendly. Trees that attain very large mature sizes are feared

for this apart from the fact that they are also associated with attracting feared birds such as owls. Owls, in this

community are associated with bad spirits and trees that would encourage their presence or visits are not liked.

Relative slow growth is characteristic of many indigenous species and not many farmers are encouraged by this.

However, naturally regenerated seedlings of these species will be protected as long as they are in the right

site. Alternatively they would just be left to grow on their own, untended, especially if they grow outside the

homestead. In Zambia it is perceived that only God can plant forest trees and thus planting of indigenous tree

species is culturally discouraged (Warner, 1993). This is a similar attitude as in the study area.

A high proportion of farmers (40%) depend on government tree nurseries for seedlings to plant (Figure

2). Reasons for this high dependency on government nurseries may include price of seedlings in other nurseries,

labour and other resource shortages as also found out by Sikuku et al (2014) among farmers in Lugari, Western

Kenya. All the recorded fourteen (14) exotic species are propagated artificially. Their relative fast growth and

almost immediate economic returns are a major incentive to their propagation. Sikuku et.al (2014) has

demonstrated that famers recognize the commercial value of trees and as such target specific species

(Eucalyptus spp., Cupressus spp and Grevillea robusta) to be raised for cash. The same situation applies in this

study area.

Locations where the tree species are grown in the home garden

The sitting of planting of any species is closely related to the purpose for planting (Figure 3). Within

the homestead 34% (highest) of the farmers planted for shade and ornamental purposes compared to only 7%

who planted for the same purpose outside the homestead. Trees for domestic use would find almost equal

consideration for space within and outside the homestead (29% and 31% of farmers respectively). In this case

space for planting would likely determine whether it is planted within or outside the homestead. Medicinal

plants would be planted almost equally as much within and outside the homestead (16% and 15% of farmers

respectively). Trees purposed for sale would find their place mainly outside the homestead. The consideration

for this would most likely be space availability for raising commercial scale plantations compare 4% for

within homestead and 21% of farmers for outside the homestead (Figure 3). Accessibility to products and

services provided by the planted species, apart from other socio-cultural considerations, seem to play important

roles in determining planting sites of the species (Figure 3 and Table 7). Figure 4 shows some species which the

community has serious reservations on planting because of superstitious views. The species are therefore either

not to be planted within homesteads or not recommended for planting at all. Erythrina abyssinica is not

preferred for planting within the homestead and it will hardly be regenerated artificially because it is a species

with many myths and superstitions around it. Oaths are taken using it, thus is not favoured for planting.

Velonica flumbago (Rachier) is associated with witchcraft and a home in which it grows, whether planted or

DOI: 10.9790/2380-08321825

www.iosrjournals.org

24 | Page

The Influence Of Socio-Cultural Aspects Of Ethnobotany On Tree Species Propagation

naturally regenerated, is associated with witchcraft because the tree is used for witchcraft (Nawi in the local

dialect). Terminalia mentaly, though a beautiful ornamental and shade tree is not a favourite in most homes and

very few homes would have it planted in the homestead (Table 7). It is associated with death, such that as it

grows up and puts up its layered branching characteristic, members of the home would be dying, one after

another. The values and symbolisms attached to the various species by the farmers are a result of either

experience with the species or information passed on from older generations. Socio-economic values are

experienced while the spiritual and cultural values are mainly information passed on from older generations and

believed as such. Ethnobotanical knowledge encompasses both wild and domesticated species, and is rooted in

observation, relationship, needs, and traditional ways of knowing. Such knowledge evolves over time, and is

therefore

always

changing

and

adding

new

discoveries,

ingenuity

and

methods

(www.botanicaldimensions.org/).

V.

Conclusions

Traditional knowledge systems seem to count when it comes to deciding on what species to plant and

where to plant them. This especially applies to indigenous species. Exotic species rarely have any spiritual

attachments but mainly socio-economic. Species would thus be planted or not planted, nurtured or not

depending on the values and symbolisms attached to them. The planting site apart from being related to the use

and even space availability will be influenced by the cultural values attached to the species. It is apparent that

planted species or species natured and the specific sites where they are found in the farm are determined by the

knowledge and experience with them - the knowledge is derived from ethnobotany of the local area.

Ethnobotanical knowledge can therefore be used to predict the choice of tree species to be propagated in home

gardens in this community.

VI.

Recommendations

Species choice and planting site has to consider both biophysical and appreciate socio-cultural values

attached to the species, the latter being the consideration of the influences that culture has on society and, which

can, in part, determine the social acceptability of agroforestry at the farmers level, as farmers are considered to

be the primary beneficiaries of agroforestry and social forestry practices.

There is real need to deeply research and establish the basis for the superstitious views on tree species

not just in this community but also in other communities in Kenya.

References

[1].

[2].

[3].

[4].

[5].

[6].

[7].

[8].

[9].

[10].

[11].

[12].

[13].

[14].

[15].

[16].

Atangana Alain, Khasa Damase , Chang Scott, and Degrande Ann (2014). Socio-Cultural Aspects of Agroforestry and Adoption.

Tropical Agroforestry 2014, pp 323-332.

Chepkwony Adam K. arap (2014). Return and Pick it. An Introduction to African Counseling and Therapy. Kacece Publications,

Kericho, Kenya. Pp. 174. ISBN 978-996-0-9.

Evans Richard (1994). The American journal of economic and sociology.

FAO (1986). Tree Growing by Rural People. FAO Forestry Paper 64, FAO, Rome.

FAO, (1983). Forest Extension Organization, FAO, Rome.

Foley G. and Benard G. (1983). Farm and community, Tech: Rep. No. 3 IIED, London pp 236.

Global Journal of Environmental Science and Technology Vol. 1(1) pp 01-06, November, 2013.

Internet: Copyright@ethnobotanybd.com2010.

Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (1994). Kenya Forestry Master Plan. NAIROBI.

Nair, P. K. R. (1993).An introduction to agroforestry. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. ISBN 0-79232134-0

Nyando District Development Plan, (2009).

Ocitti J. P. (1979). African indigenous education as practiced by Acholi of Uganda. Pp. 116.

Odak A.B. (1990). Some aspects of the Luo traditional education transmitted through the oral narratives. University of Nairobi

Press, Nairobi, Kenya.

Oloo, John Odiaga (2013). Influence of traditions/customs and beliefs/norms on women in tree growing in Siaya County, Kenya.

Otsieno Fredrick Sikuku , Musa Gweya Apudo and Gilbert O. Ototo (2014). Factors Influencing Development of Farm Forestry in

Lugari District, Kakamega County, Western Kenya. IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science (IOSR-JAVS) e-ISSN:

2319-2380, p-ISSN: 2319-2372. Volume 7, Issue 7 Ver. II (July. 2014), PP 06-13.

Warner K. (1993). Patterns of farmer tree growing in Eastern Africa: A Socio Economic Analysis. Pp. 270.

DOI: 10.9790/2380-08321825

www.iosrjournals.org

25 | Page

You might also like

- Project Based Learning Tools Development On Salt Hydrolysis Materials Through Scientific ApproachDocument5 pagesProject Based Learning Tools Development On Salt Hydrolysis Materials Through Scientific ApproachInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Effects of Formative Assessment On Mathematics Test Anxiety and Performance of Senior Secondary School Students in Jos, NigeriaDocument10 pagesEffects of Formative Assessment On Mathematics Test Anxiety and Performance of Senior Secondary School Students in Jos, NigeriaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)100% (1)

- Philosophical Analysis of The Theories of Punishment in The Context of Nigerian Educational SystemDocument6 pagesPhilosophical Analysis of The Theories of Punishment in The Context of Nigerian Educational SystemInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- The Effect of Instructional Methods and Locus of Control On Students' Speaking Ability (An Experimental Study in State Senior High School 01, Cibinong Bogor, West Java)Document11 pagesThe Effect of Instructional Methods and Locus of Control On Students' Speaking Ability (An Experimental Study in State Senior High School 01, Cibinong Bogor, West Java)International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Necessary Evils of Private Tuition: A Case StudyDocument6 pagesNecessary Evils of Private Tuition: A Case StudyInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Study The Changes in Al-Ahwaz Marshal Using Principal Component Analysis and Classification TechniqueDocument9 pagesStudy The Changes in Al-Ahwaz Marshal Using Principal Component Analysis and Classification TechniqueInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Geohydrological Study of Weathered Basement Aquifers in Oban Massif and Environs Southeastern Nigeria: Using Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System TechniquesDocument14 pagesGeohydrological Study of Weathered Basement Aquifers in Oban Massif and Environs Southeastern Nigeria: Using Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System TechniquesInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Youth Entrepreneurship: Opportunities and Challenges in IndiaDocument5 pagesYouth Entrepreneurship: Opportunities and Challenges in IndiaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)100% (1)

- Students' Perceptions of Grammar Teaching and Learning in English Language Classrooms in LibyaDocument6 pagesStudents' Perceptions of Grammar Teaching and Learning in English Language Classrooms in LibyaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Development of Dacum As Identification Technique On Job Competence Based-Curriculum in High Vocational EducationDocument5 pagesDevelopment of Dacum As Identification Technique On Job Competence Based-Curriculum in High Vocational EducationInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Child Mortality Among Teenage Mothers in OJU MetropolisDocument6 pagesChild Mortality Among Teenage Mothers in OJU MetropolisInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Success of Construction ProjectDocument10 pagesFactors Affecting Success of Construction ProjectInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Enhancing Pupils' Knowledge of Mathematical Concepts Through Game and PoemDocument7 pagesEnhancing Pupils' Knowledge of Mathematical Concepts Through Game and PoemInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Need of Non - Technical Content in Engineering EducationDocument3 pagesNeed of Non - Technical Content in Engineering EducationInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Lipoproteins and Lipid Peroxidation in Thyroid DisordersDocument6 pagesLipoproteins and Lipid Peroxidation in Thyroid DisordersInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Comparison of Psychological Variables Within Different Positions of Players of The State Junior Boys Ball Badminton Players of ManipurDocument4 pagesComparison of Psychological Variables Within Different Positions of Players of The State Junior Boys Ball Badminton Players of ManipurInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Comparison of Selected Anthropometric and Physical Fitness Variables Between Offencive and Defencive Players of Kho-KhoDocument2 pagesComparison of Selected Anthropometric and Physical Fitness Variables Between Offencive and Defencive Players of Kho-KhoInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Advancing Statistical Education Using Technology and Mobile DevicesDocument9 pagesAdvancing Statistical Education Using Technology and Mobile DevicesInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Study of Effect of Rotor Speed, Combing-Roll Speed and Type of Recycled Waste On Rotor Yarn Quality Using Response Surface MethodologyDocument9 pagesStudy of Effect of Rotor Speed, Combing-Roll Speed and Type of Recycled Waste On Rotor Yarn Quality Using Response Surface MethodologyInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Microencapsulation For Textile FinishingDocument4 pagesMicroencapsulation For Textile FinishingInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Comparative Effect of Daily Administration of Allium Sativum and Allium Cepa Extracts On Alloxan Induced Diabetic RatsDocument6 pagesComparative Effect of Daily Administration of Allium Sativum and Allium Cepa Extracts On Alloxan Induced Diabetic RatsInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Auxin Induced Germination and Plantlet Regeneration Via Rhizome Section Culture in Spiranthes Sinensis (Pers.) Ames: A Vulnerable Medicinal Orchid of Kashmir HimalayaDocument4 pagesAuxin Induced Germination and Plantlet Regeneration Via Rhizome Section Culture in Spiranthes Sinensis (Pers.) Ames: A Vulnerable Medicinal Orchid of Kashmir HimalayaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Core Components of The Metabolic Syndrome in Nonalcohlic Fatty Liver DiseaseDocument5 pagesCore Components of The Metabolic Syndrome in Nonalcohlic Fatty Liver DiseaseInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Comparison of Explosive Strength Between Football and Volley Ball Players of Jamboni BlockDocument2 pagesComparison of Explosive Strength Between Football and Volley Ball Players of Jamboni BlockInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Application of Xylanase Produced by Bacillus Megaterium in Saccharification, Juice Clarification and Oil Extraction From Jatropha Seed KernelDocument8 pagesApplication of Xylanase Produced by Bacillus Megaterium in Saccharification, Juice Clarification and Oil Extraction From Jatropha Seed KernelInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- A Review On Refrigerants, and Effects On Global Warming For Making Green EnvironmentDocument4 pagesA Review On Refrigerants, and Effects On Global Warming For Making Green EnvironmentInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Investigation of Wear Loss in Aluminium Silicon Carbide Mica Hybrid Metal Matrix CompositeDocument5 pagesInvestigation of Wear Loss in Aluminium Silicon Carbide Mica Hybrid Metal Matrix CompositeInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Parametric Optimization of Single Cylinder Diesel Engine For Specific Fuel Consumption Using Palm Seed Oil As A BlendDocument6 pagesParametric Optimization of Single Cylinder Diesel Engine For Specific Fuel Consumption Using Palm Seed Oil As A BlendInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Research Analysis On Sustainability Opportunities and Challenges of Bio-Fuels Industry in IndiaDocument7 pagesResearch Analysis On Sustainability Opportunities and Challenges of Bio-Fuels Industry in IndiaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Bonsai by Brent WaltsonDocument5 pagesBonsai by Brent WaltsonartlinefoxNo ratings yet

- GB50660-2011 - en Code For Design of Large and Medium-Sized Thermal Power PlantsDocument173 pagesGB50660-2011 - en Code For Design of Large and Medium-Sized Thermal Power PlantsCourage MurevesiNo ratings yet

- SOAL USBN Bahasa Inggris 2019-2020Document5 pagesSOAL USBN Bahasa Inggris 2019-2020mazidah xiuNo ratings yet

- Jurnal KesehatanDocument8 pagesJurnal KesehatanrilleyNo ratings yet

- Performance of Varieties and Effect of Date of Sowing On Growth and Yield of WheatDocument4 pagesPerformance of Varieties and Effect of Date of Sowing On Growth and Yield of WheatEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Modern Rice Milling: Presentation Title Goes HereDocument16 pagesModern Rice Milling: Presentation Title Goes HereTowfiqul Islam KhanNo ratings yet

- B 4 Ev 6 y 22 WR Getting 20 To 20 Know 20 Plants 20 PPTDocument46 pagesB 4 Ev 6 y 22 WR Getting 20 To 20 Know 20 Plants 20 PPTatharNo ratings yet

- Create Beautiful Glowing FlowersDocument10 pagesCreate Beautiful Glowing FlowersshilpashreeNo ratings yet

- 0 Clasa A Va Etapa Pe ScoalaDocument4 pages0 Clasa A Va Etapa Pe ScoalaMihaela Monica MotorcaNo ratings yet

- Science Notes Jagran JoshDocument191 pagesScience Notes Jagran Joshनितीन लाठकरNo ratings yet

- Melbourne Water Wetland Design GuideDocument32 pagesMelbourne Water Wetland Design GuideBere QuintosNo ratings yet

- Demonstrative Speech About GardeningDocument1 pageDemonstrative Speech About GardeningMayurikaa SivakumarNo ratings yet

- CBR Laboratorium PB - 0113 - 76 AASHTO T - 193 - 74Document2 pagesCBR Laboratorium PB - 0113 - 76 AASHTO T - 193 - 74Gung SuryaNo ratings yet

- Life Cycle of CycasDocument12 pagesLife Cycle of CycasRahul DeyNo ratings yet

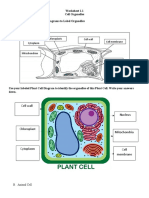

- Worksheet 1.1 Cell OrganelleDocument2 pagesWorksheet 1.1 Cell OrganelleCyndel TindoyNo ratings yet

- Aconitum HeterophyllumDocument6 pagesAconitum HeterophyllumAnonymous NEJodF0HXqNo ratings yet

- First Quarter Assessment in AgricultureDocument7 pagesFirst Quarter Assessment in Agriculturearlene dioknoNo ratings yet

- Valves in High Temperature Services: Technical SpecificationDocument7 pagesValves in High Temperature Services: Technical SpecificationvajithaNo ratings yet

- Iss 1 AT647 Multilingual PDFDocument93 pagesIss 1 AT647 Multilingual PDFAnonymous iDNa91FVNo ratings yet

- Flower StructureDocument16 pagesFlower Structurevaishnavi100% (1)

- Los Dynastinae de El Salvador, Honduras y NicaraguaDocument12 pagesLos Dynastinae de El Salvador, Honduras y NicaraguaRuben Sorto100% (1)

- What Are Essential OilsDocument4 pagesWhat Are Essential OilsstanNo ratings yet

- Roi2 M 304 Fourth Class End of Year Maths Assessment Sheet - Ver - 3.pdf - 2 - PDFDocument11 pagesRoi2 M 304 Fourth Class End of Year Maths Assessment Sheet - Ver - 3.pdf - 2 - PDFEmma TurquoiseNo ratings yet

- Fertilizer Trials On Performance of Aloe-Vera: ArticleDocument5 pagesFertilizer Trials On Performance of Aloe-Vera: ArticleRómulo Del ValleNo ratings yet

- Breeding and Seed Production of Organic Vegs - Beta - PCRD-H003439Document48 pagesBreeding and Seed Production of Organic Vegs - Beta - PCRD-H003439Ervin Brian Tapales SumalinogNo ratings yet

- Alternative Drainage Erosion ControlDocument46 pagesAlternative Drainage Erosion ControlLbalinNo ratings yet

- TranspirationDocument22 pagesTranspirationyr44grf94kNo ratings yet

- HCG Tracking FormsDocument6 pagesHCG Tracking Formswoowoo3No ratings yet

- Lee Labrada Lean Body NutritionDocument7 pagesLee Labrada Lean Body NutritionShakil AhmedNo ratings yet

- Planificare - Fairyland CLS 2Document3 pagesPlanificare - Fairyland CLS 2dianaNo ratings yet