Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Arbitration A Guide To International Arbitration 26050

Uploaded by

aleksandraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Arbitration A Guide To International Arbitration 26050

Uploaded by

aleksandraCopyright:

Available Formats

Financial institutions

Energy

Infrastructure, mining and commodities

Transport

Technology and innovation

Life sciences and healthcare

A basic guide to

international arbitration

Norton Rose Fulbright

Norton Rose Fulbright is a global legal practice. We provide the worlds preeminent

corporations and financial institutions with a full business law service. We have more than

3800 lawyers and other legal staff based in more than 50 cities across Europe, the United

States, Canada, Latin America, Asia, Australia, Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia.

Recognized for our industry focus, we are strong across all the key industry sectors: financial

institutions; energy; infrastructure, mining and commodities; transport; technology and

innovation; and life sciences and healthcare.

Wherever we are, we operate in accordance with our global business principles of quality,

unity and integrity. We aim to provide the highest possible standard of legal service in each of

our offices and to maintain that level of quality at every point of contact.

Norton Rose Fulbright US LLP, Norton Rose Fulbright LLP, Norton Rose Fulbright Australia,

Norton Rose Fulbright Canada LLP and Norton Rose Fulbright South Africa Inc are separate

legal entities and all of them are members of Norton Rose Fulbright Verein, a Swiss verein.

Norton Rose Fulbright Verein helps coordinate the activities of the members but does not

itself provide legal services to clients.

References to Norton Rose Fulbright, the law firm, and legal practice are to one or more of the Norton Rose Fulbright members or to one of their

respective affiliates (together Norton Rose Fulbright entity/entities). No individual who is a member, partner, shareholder, director, employee or

consultant of, in or to any Norton Rose Fulbright entity (whether or not such individual is described as a partner) accepts or assumes responsibility,

or has any liability, to any person in respect of this communication. Any reference to a partner or director is to a member, employee or consultant with

equivalent standing and qualifications of the relevant Norton Rose Fulbright entity. The purpose of this communication is to provide information

as to developments in the law. It does not contain a full analysis of the law nor does it constitute an opinion of any Norton Rose Fulbright entity on

the points of law discussed. You must take specific legal advice on any particular matter which concerns you. If you require any advice or further

information, please speak to your usual contact at Norton Rose Fulbright.

Norton Rose Fulbright LLP NRF20889 02/15 (UK) Extracts may be copied provided their source is acknowledged.

A basic guide to international arbitration

The preferred option

Arbitration is a consensual, binding method of dispute resolution. It is an increasingly

popular means of resolving disputes, particularly in relation to international contracts.

There are many reasons for choosing arbitration but the key ones are given below.

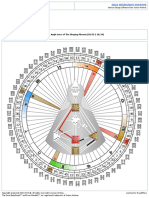

Signatories to the New York Convention on the

Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards 1958

Greenland

Turkmenistan

Iraq

Western Sahara

North Korea

Libya

Tajikistan

Yemen

Eritrea

Ethiopia

South Sudan

Angola

Malawi

Namibia

Papua New

Guinea

Somalia

Togo

French Guiana

Equatorial Guinea

Suriname

Congo

Taiwan

Sierra Leone

Guinea-Bissau

Belize

Sudan

Chad

Gambia

Swaziland

Country status

Member

Non-member

Data source: UNCITRAL

1,250 2,500

5,000

km

NRF20634

Enforcement

Arbitration awards can be easier to enforce internationally

than the judgments of national courts. The United Nations

Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign

Arbitral Awards 1958 known as the New York Convention

has been ratified by 154 countries. This means that, in

principle, an arbitration award can be enforced in any of

those countries. By contrast, court judgments are generally

only enforceable in countries where there are reciprocal

enforcement arrangements in place.

So, for example, whilst an English court judgment can

be enforced easily in any EU state through the Brussels

Regulation on the Recognition and Enforcement of

Judgments, it can be difficult to enforce an English court

judgment in many other countries. By contrast, an English

arbitration award can be enforced in 154 countries.

Where the assets of the potential defendant are in a country

where a national court judgment cannot be enforced,

arbitration is the obvious choice.

See page 09 on enforcement.

See www.uncitral.org for the text of the New York Convention

and a list of signatories.

Norton Rose Fulbright February 2015 03

A basic guide to international arbitration

Neutrality and confidentiality

Parties to international contracts often want to avoid using

the home courts of one of the parties in order to ensure

neutrality. In addition, arbitration avoids problems with

unfamiliar or unpredictable local court procedures.

Court proceedings are usually public, whereas the parties

can agree to keep arbitration proceedings confidential. In

this way, the parties can protect commercial practices, trade

secrets, industrial processes and knowledge of the dispute

itself. In some countries, however, confidentiality may be

lost if arbitration proceedings end up in court for example,

if the arbitration award is appealed.

If confidentiality is important then it is sensible to include

a confidentiality provision in the arbitration agreement.

See page 06 on drafting confidentiality clauses.

Finality

The parties can, subject to the applicable procedural law,

agree that an arbitration award is final and binding, and

cannot be appealed to a court. In many jurisdictions, awards

(particularly those in domestic arbitration) will not be set

aside on the ground of errors of fact or will only be set aside

in very exceptional circumstances. Whilst most jurisdictions

permit the parties to agree not to appeal to the courts on a

point of law, in many jurisdictions the right to appeal on

grounds of serious procedural irregularity is mandatory and

cannot be excluded, even by agreement. The ability to restrict

appeals on points of law means that arbitration proceedings

can be concluded more quickly than court proceedings.

Choice

In arbitration, the parties have considerable choice over the

way in which their dispute is conducted. They can choose in

which country, city and, even, in which building they wish

to hold their arbitration (although, unlike court proceedings,

they will have to pay for the venue).

The parties are also free to select the arbitrators themselves.

This can be helpful where the dispute is of a technical

nature, since they can ensure that the arbitrators have

particular technical skills or expertise. (Bear in mind,

however, that, unlike judges, arbitrators must be paid by the

parties.) It is important to agree to the appointment of an odd

number of arbitrators (either a sole arbitrator or a panel of

three): if two, or four, arbitrators are selected, the panel may

be unable to reach a decision due to deadlock.

04 Norton Rose Fulbright February 2015

The language(s) in which the arbitration is conducted can

also be specified by the parties.

The legal framework

International arbitration is subject to a number of layers of

regulation and in this respect is more complex in structure

than national court litigation. What follows is a summary of

the different laws and rules that make up this framework.

The law governing the contract

The substantive law of the contract between the parties

is the law governing the contract. Regardless of where

the arbitration takes place, the arbitrators will apply the

substantive law of the contract when deciding the issues

in dispute under the contract.

The law governing the arbitration agreement

It must be remembered that the arbitration clause within the

main contract is a contract in its own right, collateral to the

main contract. It is, in effect, a contract within a contract and

is severable from the main contract.

If the arbitration agreement is contained within the main

contract, the law of the main contract will usually govern

the arbitration agreement (if no other law is chosen by the

parties to govern the arbitration agreement and generally

none is). However, if an arbitration agreement is entered

into after the main contractual dispute has arisen (because

the main contract contains no arbitration clause), it will

not necessarily follow that the arbitration agreement will

be governed by the same law as the main agreement (if no

separate choice of law is made in the arbitration agreement).

Although it is by far the most usual case that the arbitration

agreement is governed by the same law as the main contract,

it is possible to provide for the law of the arbitration

agreement to be a different governing law from that of the

main contract. Institutional rules such as the ICC Rules

do not deal with the governing law of the arbitration

agreement. Their standard clauses do not include a choice

of law clause for the arbitration agreement itself but they

do stress the desirability of stipulating the governing law of

the main contract.

A basic guide to international arbitration

The law governing the arbitration agreement covers

substantive matters relating to the agreement to arbitrate, as,

for example, the interpretation and validity of the agreement

to arbitrate. The issue of whether a particular dispute falls

within the terms of an arbitration clause will be governed by

the law governing the arbitration agreement.

It will also be relevant to issues relating to the recognition

and enforcement of the award. For example, under article 5

of the New York Convention, recognition and enforcement of

an award may be refused if the arbitration agreement is not

valid under the law to which the parties have subjected it.

The procedural law

The law of the place of recognition and

enforcement of the award

The law of the place of recognition and enforcement of any

potential award should also be considered. Is the country a

signatory to the New York Convention? What is that countrys

national courts reputation in relation to ease of enforcement

of arbitration awards? There can be substantial differences in

the approach of local courts to the enforcement of a foreign

arbitration award. It is important to obtain local advice at the

outset (preferably when drafting the dispute resolution clause)

on the prospects of enforcing an award in a particular jurisdiction.

See page 03 on enforcement and the New York Convention.

The nature and scope of the law of the seat of the arbitration

determines the procedure for the arbitration. Clients will

often require that the place at which any arbitration is to

take place is a place that is neutral to all parties. It is vitally

important to ensure that, when selecting a seat for the

arbitration, the requirements and scope of the laws of that

place of arbitration are understood. Different countries

can import different requirements into their own law and,

to be effective, an award will have to comply with all the

mandatory requirements imposed by the law of the seat of

the arbitration.

The procedural rules of the arbitration

The procedural law acts in concert with the institutional

or ad hoc rules (if any) under which the arbitration is to

be conducted. The procedural law and the rules govern

the conduct of the arbitration; by adopting certain rules,

the parties may find that they have contracted into or opted

out of various of the default non-mandatory provisions of the

procederal law.

An arbitration is ad hoc when it is not administered by an

arbitration institution. In theory, it is possible for the parties

to write their own rules but this is rarely, if ever, done in

practice. Instead, the parties use the procedural rules that

either they have chosen or on which the arbitrator(s) has

decided. Alternatively, the arbitration may be governed solely

by the procedural law of the arbitration.

Typically, the procedural law covers questions relating,

for example, to the arbitral tribunal itself, such as its

appointment and any revocation of its authority, its powers

and duties and remedies for any breach of duty. It also

determines the availability of interim and procedural

remedies. The form and validity of the award and grounds

for challenges to the award where challenge is made at the

place of arbitration will also be determined by the procedural

law. In some instances, the law of the seat of the arbitration

can also stipulate that a particular type of dispute cannot

be settled by arbitration under local law. In some states, if

the proper law of the contract has not been chosen by the

parties, it is normally determined by the conflict of law rules

of the procedural law: this enables the tribunal to work out

which national law to apply to interpret the procedural laws

applying to the contract usually the law of the place where

the arbitration is taking place.

See pages 08 for a discussion of the relative merits of

institutional and ad hoc arbitrations.

The parties can (within the constraints of the procedural

law) choose their own rules to govern the procedure. There

are essentially two options here: institutional rules or ad hoc

procedures.

Institutional rules are chosen when the arbitration is

administered by an arbitration institution. The rules of the

major institutions are well known and their application is

reasonably predictable.

The powers of the tribunal

The authority of the tribunal (or panel of arbitrators) comes

from the contractual arbitration agreement between the

parties. The powers of the tribunal are set out in the relevant

procedural law and procedural rules. The limits of the

arbitrators powers will therefore differ, depending on the

procedural law and rules chosen.

The powers of the court

The powers of the court to hear applications relating

to an arbitration will be determined by the procedural

Norton Rose Fulbright February 2015 05

A basic guide to international arbitration

law of the arbitration, the procedural rules chosen (if

any) and the arbitration agreement. All three of these will

affect whether a particular court can hear an appeal of an

arbitration award, consider the jurisdiction of the arbitral

tribunal or provide interim relief (such as freezing orders)

in support of the arbitration.

Drafting arbitration clauses

No one arbitration clause will be suitable for all agreements.

The benefit of arbitration is that it can be tailored to meet the

needs of the parties.

That said, the key to drafting a successful arbitration clause

is simplicity. This principle applies in the most complex

of situations, including multiparty disputes and resolving

disputes arising out of a group of related but separate contracts.

A skilfully engineered, straightforward clause will enable the

parties to avoid further conflict once a dispute has arisen.

Before agreeing on an arbitration clause, it is important to

consider the issues set out below.

Location of assets

Identify where the other partys assets are located now

and where they are likely to be located after any award

is obtained. If they are located in the country where the

award will be obtained, can the local courts be relied upon

to enforce the award? If the assets are located outside the

jurisdiction in which the award will be obtained, seek

advice on the recognition and enforcement of arbitration

awards against assets in that country, both in theory and in

practice. An arbitration award is of no value unless it can be

effectively enforced.

Type of arbitration

Decide whether the arbitration should be institutional and

administered according to the rules of the institution (and if

so which institution) or ad hoc with no formal administration

agency, where the parties create their own rules and procedures.

Choice of seat

Before choosing a particular seat, consider the extent

to which the local courts will support the arbitration

proceedings (by, for example, providing interim relief

such as injunctions or conservatory measures).

Model clauses

Most arbitration institutions provide recommended model

arbitration clauses. These make a good starting point when

drafting arbitration clauses. Variations to a model clause

can lead to undesirable results if not carefully drafted. The

meaning of a poorly drafted arbitration clause can be the

subject of separate proceedings, leading to increased costs

and delay. In the worst case, the clause may be found to be

ineffective. It is also important to consider how an arbitration

clause will be viewed by the state in which the award will be

enforced. A poorly drafted clause can lead to problems with

enforcement.

Mandatory

There are seven basic elements that must be included in

your clause.

Protection

Referral of the existing or future dispute to arbitration

Draft the clause in broad terms to ensure that all disputes,

tortious or contractual, are referred to arbitration.

Wording such as all disputes and claims arising out of

or in connection with this Agreement will be referred to

arbitration is recommended. When drafting a clause for a

group of contracts, include a reference to the arbitration

clause in the main contract.

If one of the parties to the agreement is a State, consider

whether the ICSID Convention can apply and whether there

is scope for investment treaty protection (through bilateral or

multilateral investment treaties).

Incorporation of rules governing the arbitration

The parties may select rules in order to regulate the conduct

of the arbitration. They may be the rules of an institution,

such as the ICC, or ad hoc rules, such as the UNCITRAL rules.

See page 09 on investment treaties.

See page 08 for more information on UNCITRAL.

06 Norton Rose Fulbright February 2015

A basic guide to international arbitration

Reference to the place of arbitration

The place of arbitration, which is often referred to as the

seat of arbitration, is important for three reasons: firstly, it

determines the place where the award is made or published

(and hence whether the award will be treated as an award of

a party state for the purposes of the New York Convention);

secondly, the arbitration will be subject to the procedural

law, including the arbitration laws, of the jurisdiction

in which the place is located; thirdly, the courts of that

jurisdiction will have a supervisory or supportive function

in connection with the arbitration itself (and the parties can

ascertain in advance to what extent the courts will issue

interim relief or entertain appeals).

Reference to the place of hearing

The parties may wish to agree that hearings be held at a

place other than the place or seat of arbitration. However,

they should first check to ensure that this is permissible

under the law of the place of arbitration.

The choice of language

The parties should agree on the language of the arbitration,

as this will be the language of the pleadings and the hearings.

The preferred number of arbitrators

Three arbitrators should generally be appointed in anything

but a simple, low value case. Qualifications, such as industry

experience, may be stipulated.

right to appeal in any circumstances (including procedural

irregularity), but this is not recommended as it leaves the

parties with no redress in the event of an abuse of process.

Service of process provision

Although the strict rules on court service do not apply,

the inclusion of a service provision (specifying on whom

and where documents should be served) makes service of

proceedings straightforward.

Waiver of sovereign immunity

If contracting with a state or stateowned body, it is important

to include a waiver of sovereign immunity clause to enable

any award to be enforced.

Stepped clauses

Stepped clauses allow for different methods of dispute

resolution at different stages of the dispute. These clauses

can be helpful in some situations, as they require the parties

to attempt to resolve their differences at an early stage before

formal proceedings have begun. In other situations, they can

simply lead to delay. Care should be taken to ensure that they

are enforceable within the particular jurisdiction.

Reference to the substantive law of the agreement

or contract

This is the law that will govern the merits of the dispute.

Interim measures

The ability to apply to the arbitral tribunal or national courts

for interim relief depends on the chosen procedural law

and the powers given to the arbitrators under any agreed

rules governing the arbitration and the arbitration clause

itself. It is important to consider this issue when drafting the

arbitration clause and, if necessary, to extend the powers of

the arbitrators.

Optional

Drafting confidentiality clauses

It can at times be useful even essential to include some

or all the following elements.

Multiple related contracts

Where there are interrelated contracts, it would be sensible

for the parties to consider whether disputes arising under the

different contracts should be consolidated into one hearing,

heard concurrently or resolved by the same tribunal. This is

not a straightforward matter, and it is wise to seek detailed

advice on a case by case basis.

Third parties cannot be joined to arbitration proceedings

without their consent. If this is likely to be an important

issue, then litigation should be considered instead.

Excluding rights to appeal

Parties can exclude (as far as is permissible by the laws of the

relevant state) the right to appeal on a point of law, in order

to ensure any award is final and binding at the end of the

arbitration. In some jurisdictions it is possible to exclude the

In some jurisdictions confidentiality of the proceedings and

the award is implied during the arbitration and protected in

any related court proceedings. However, in many jurisdictions

this is not the case. If confidentiality is important to the

parties then a confidentiality provision, such as the clause

below, should be added to the arbitration agreement.

General confidentiality clause

The Arbitral Tribunal shall maintain the confidentiality of

the arbitration and conduct the arbitration in an impartial,

practical and expeditious manner, giving each party

sufficient opportunity to present its case.

Unless the parties expressly agree in writing to the contrary,

the parties undertake to keep confidential all awards and

orders in their arbitration as well as all materials in the

arbitral proceedings created for the purpose of the arbitration

and all other documents produced by another party in the

arbitral proceedings not otherwise in the public domain,

save to the extent that disclosure is required of a party by a

Norton Rose Fulbright February 2015 07

A basic guide to international arbitration

legal duty, to protect or pursue a legal right or to enforce or

challenge an award in legal proceedings before a state court

or other judicial authority.

Ad hoc arbitration

Adapted from the rules of the Arbitration Institute of the

Stockholm Chamber of Commerce and of the London Court

of International Arbitration.

Ad hoc, or unadministered, arbitration can be flexible,

relatively cheap and fast if the parties cooperate. It works

best when conducted in a jurisdiction with a recognised

arbitration law.

Institutional arbitration

When parties are not able to cooperate, the assistance of

an institution to move the arbitration forward can be very

helpful. However, since ad hoc arbitration is cheaper (there

are no institutional fees to pay), it can be a popular choice.

There are a number of benefits to conducting arbitration

under the auspices of one of the major institutions.

Firstly, the arbitration institution will supervise the

conduct of the arbitration. It will assist in the appointment

of arbitrators and will give practical guidance on how to

interpret its procedural rules. Some institutions (notably the

ICC) will review the arbitration award and recommend any

changes to the tribunal. This adds another layer of protection

against errors in the arbitration award of particular

importance when the ability to appeal an award has been

curtailed through the arbitration clause, the procedural rules

or procedural law.

Secondly, the institution can act as an appointing authority.

Arbitration clauses can provide that the institution is

responsible for appointing the chair arbitrator after the

parties have each nominated one arbitrator on a three person

panel or that the institution appoint the entire panel of one

or three arbitrators. The institution can also appoint an

arbitrator if one party fails to nominate an arbitrator. In this

respect, arbitration institutions can act as a form of quality

control, appointing arbitrators with appropriate experience

and a proven track record.

A third benefit in using institutional arbitration is that it

can make the recognition of an award more straightforward,

since the procedures adopted by the institution will be well

known and less open to challenge.

Arbitration institutions charge a fee for the administration

of the arbitration and this can make administered

arbitrations more expensive. However, the predictability

of institutional rules and the assistance of the institution in

administering the arbitration can lead to fewer procedural

difficulties, which may reduce time and costs. It is important

to consider the way in which the institutions fees are

structured, as the proportion of fees required at an early

stage in the arbitration varies.

08 Norton Rose Fulbright February 2015

It is possible to have an ad hoc arbitration with an institution

designated as the appointing authority. This can solve one of

the difficulties associated with ad hoc arbitration namely,

constituting the tribunal itself. In such circumstances, parties

can also choose, once the tribunal has been constituted, to

have the arbitration administered by the institution as well.

UNCITRAL

UNCITRAL is the United Nations Commission on International

Trade Law. It exists to make the rules of international

business simpler, clearer and more contemporary; it was

established in 1966. The UN General Assembly elects 60

member states to form the Commission for a term of six

years apiece. Their goal is commercial law reform, allowing

international trade to flow smoothly and disputes to be

settled in good order.

UNCITRAL rules

UNCITRAL does not act as an arbitration institution or

administer arbitrations, but it has created a set of procedural

rules: the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules. These rules are

widely used in ad hoc (or unadministered) arbitrations.

UNCITRAL model law

The UNCITRAL rules should be distinguished from the

UNCITRAL model law. This is a recommended pattern or

template for lawmakers in national governments to consider

adopting as part of their domestic legislation on arbitration.

Many national arbitration laws are based on the UNCITRAL

model law.

IBA

The International Bar Association (IBA) provides rules on

taking evidence in international commercial arbitrations

that are commonly used. The IBA also provides guidelines

on conflicts of interest in international arbitration which

are used to deal with conflict issues relating to arbitral

appointments. The IBA also produced guidelines governing

party representation in international arbitration. These rules

are widely available on the Internet.

A basic guide to international arbitration

Enforcement

One advantage of arbitration over other forms of dispute

resolution is the ease with which awards can be enforced in

other states. The New York Convention is the primary tool for

enforcement and has been ratified by (to date) 154 countries.

The wide acceptance of the New York Convention across the

worlds industrialised countries is recognised as one of the

greatest achievements of public international law.

The New York Convention

The New York Convention is the United Nations Convention

on Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards,

New York, 1958.

See www.uncitral.org for the full text.

The New York Convention deals with the recognition and

enforcement of foreign arbitration awards. (Foreign for

these purposes means an award made in a state other than

that where the recognition and enforcement is sought.) It

has been signed and ratified by most industrial states and

provides the mechanism by which international arbitration

awards are enforced around the world.

See www.uncitral.org for a list of signatories.

Thanks to the New York Convention, arbitration awards can

be enforced where it would be impossible to enforce a similar

judgment from a national court.

By signing up to the New York Convention, a contracting

state agrees that it will recognise an agreement in writing

between parties who have undertaken to submit to

arbitration all or any differences which have arisen in respect

of a defined legal relationship, whether contractual or not.

A contracting state also affirms that it will recognise

arbitration awards as binding, and that it will enforce them

in accordance with the procedural rules of the territory

where the award is to be enforced. It also agrees that it will

not impose substantially more onerous conditions or higher

fees or charges on the recognition and enforcement of foreign

awards than are imposed on the recognition or enforcement

of domestic awards.

Refusal to enforce

There are a limited number of circumstances in which a court

in the relevant state may refuse to enforce an arbitration award.

The agreement is not valid under the law to which the

parties have subjected it, or the law of the country where

the award was made.

The party against whom the award was made was not

given proper notice of the proceedings.

The award deals with a difference which does not fall

within the terms of the submission to arbitration.

The arbitration procedure was not in accordance with the

agreement, or was not in accordance with the laws

of the country in which the arbitration took place.

The award has not yet become binding on the parties, or it

has been set aside or suspended by a competent authority

of the country in which the award was made.

In addition, recognition and enforcement may be refused

if the competent authority in the country of enforcement

finds that the subject matter of the dispute is not capable

of settlement under the arbitration laws of that country;

or finds that the recognition or enforcement of the award

is contrary to the public policy of that country.

Public policy is one of the most common grounds for

enforcement of an arbitral award to be refused. Although

most industrialised countries are signatories to the New York

Convention, the way that it is applied varies from jurisdiction

to jurisdiction.

Investment treaties

Bilateral

Bilateral investment treaties (BITs) are reciprocal agreements

made between two nation states which give certain

protections and benefits to investments made by citizens and

companies of the other country. The rights and obligations

arising under a BIT may be invoked by a qualifying investor

from one of the two countries to which the BIT relates

directly against the other nation state. Many BITs provide

that the rights they give can be enforced under ICSID the

governments thereby provide advance consent to submit

investment disputes to ICSID. This is not the case for all BITs;

some go to ICC or other arbitration institutions.

Since the late 1980s BITs have come to be universally

accepted instruments for the promotion and legal protection

of foreign investments; this is reflected in the rapid growth in

their number. There are now more than 3000 BITs.

Rights

The rights a BIT will provide to an investor will vary

depending on the terms of the relevant BIT. There is no

standard form of BIT; the terms of each BIT are a matter of

negotiation and agreement between the contracting States.

Norton Rose Fulbright February 2015 09

A basic guide to international arbitration

Typically, however, a BIT might confer upon investors the

rights outlined below.

Dispute resolution

This is perhaps the most useful element of any BIT for

investors. The provisions typically provide that any breach

of the BIT will entitle the investor to commence arbitration

proceedings against the relevant State. Investors are

therefore able to enforce their claims directly against the host

State in a neutral forum, thus avoiding the need for their

own government to take action and avoiding having to claim

against the host State in the courts of the host State.

Protection from expropriation/nationalisation

Each State agrees that it will not expropriate or nationalise

(or take any step having an equivalent effect) any asset or

investment belonging to nationals from the other State.

The common exception to this prohibition is where the

expropriation or nationalisation takes place for a public

purpose, is nondiscriminatory and is subject to prompt and

adequate compensation.

Most Favoured Nation and national treatment

Each State agrees that it will treat investments made by

investors from the other State in a manner that is at least as

favourable as the manner in which it treats investments made

either by investors from other States or by its own citizens.

Repatriation of investment and earnings

Each State permits the unrestricted transfer of investments

and returns made by nationals of the other State. These

transfers are to be effected without delay and in the currency

in which the investment was originally made (or in any other

convertible currency agreed by the investor).

Observe contractual obligations

Each State agrees that it will observe any obligation that it

has entered into with investors from the other State. This

type of provision will therefore give treaty protection to any

obligations undertaken in a contract between the investor

and the State, such as a concession contract or licence for

a project.

Definition of investor

Who amounts to an investor and what amounts to an

investment will vary from BIT to BIT. This is because there

is no universally accepted notion of an investment to which

BITs apply. A BIT will normally define what amounts to an

investment.

Most BITs are quite broad in this respect, and so it is possible

that various types of activity could amount to investments for

BIT purposes, depending on the facts in each case and the

wording of the BIT. This could well extend beyond perhaps

the most obvious types of activity, such as the acquisition of

10 Norton Rose Fulbright February 2015

all or some of the shares in a company in the host State, the

setting up of a new local subsidiary in the host State, or the

construction or financing of a project in the host State which

benefits the host State.

The question of who amounts to a protected investor

is usually more difficult, especially in the context of a

multinational organisation. This is because, in the context

of a group of companies based in multiple jurisdictions, the

immediate or ultimate investor may be the parent company

or some other group entity. This has to be considered on a

case by case basis.

Central register

There is no central register indicating which States have

entered into BITs with which others, or, of the BITs entered

into, which are in force. Neither is there any obligation

on States to notify any international body, for instance

the United Nations, of its BITs. Ultimately, it is a matter of

checking with both States whether they regard a BIT as

having been entered into; and whether it has been brought

into force by any necessary ratifying legislation.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

(UNCTAD) contains a search engine on its website which

is stated to set out the current status of BITs between all

countries. Although its accuracy cannot be confirmed, it

represents a starting point for any enquiry.

Multilateral

Similar protection is available under a growing number of

multilateral investment treaties (MITs); more and more MITs

which focus primarily on trade now contain provisions on

investment.

Energy Charter Treaty

One of the most effective MITs is the Energy Charter Treaty,

which came into force in April 1998. Developed on the basis

of the European Energy Charter principles, it establishes a

legal framework in order to promote long-term cooperation

in the energy eld. To date, 46 countries have ratied the

ECT and a further four countries are signatories to it. The

ECT imposes a common set of obligations on contracting

states, seeking to reduce the risks of investment and trade

in the energy sector, so encouraging investment and

stabilising energy supplies. The ECT can be invoked against

the contracting States by individuals or companies of other

contracting States and the resulting disputes are settled

through one of the mechanisms provided for in the treaty, the

choice of mechanism (generally) remaining with the investor.

For more information about the Energy Charter Treaty,

including a copy of the treaty text and a list of Members and

Observers, see www.encharter.org.

A basic guide to international arbitration

Contact

If you would like further information please contact:

Brett C. Govett

Partner, Dallas

Norton Rose Fulbright US LLP

Tel +1 214 855 8118

brett.govett@nortonrosefulbright.com

James Rogers

Partner, Hong Kong

Norton Rose Fulbright Hong Kong

Tel +852 3405 2323

james.rogers@nortonrosefulbright.com

Shea R. Haass

Senior Associate, Dallas

Norton Rose Fulbright US LLP

Tel +1 214 855 8114

shea.haass@nortonrosefulbright.com

Norton Rose Fulbright February 2015 11

Law around the world

nortonrosefulbright.com

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Foreclosure Bench Book2013Document98 pagesForeclosure Bench Book2013wiquida3213No ratings yet

- Sample Chart MMI Human DesignDocument1 pageSample Chart MMI Human DesignThe TreQQerNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Guide To International Arbitration 2014Document56 pagesGuide To International Arbitration 2014Eduardo Leardini Petter80% (5)

- Comparative International Commercial ArbitrationDocument871 pagesComparative International Commercial ArbitrationRonald Brian Martin Alarcón100% (18)

- Copyright For Tex Lee Mason Copyright NoticeDocument2 pagesCopyright For Tex Lee Mason Copyright NoticeHAN SOLONo ratings yet

- Genus Attribute Reference ManualDocument2,228 pagesGenus Attribute Reference ManualAmit HashilkarNo ratings yet

- Pilar C. de Lim Vs Sun Life AssuranceDocument2 pagesPilar C. de Lim Vs Sun Life AssurancemaggiNo ratings yet

- Internship Report On Popular Life Insurance CompanyDocument58 pagesInternship Report On Popular Life Insurance Companysrb199175% (16)

- Yu Tek Vs Gonzales (Final)Document2 pagesYu Tek Vs Gonzales (Final)dollyccruzNo ratings yet

- Navarro Vs PinedaDocument2 pagesNavarro Vs PinedaAngelNo ratings yet

- Build Loops and Discover The Deep StructureDocument1 pageBuild Loops and Discover The Deep StructurealeksandraNo ratings yet

- Arbitration A Guide To International Arbitration 26050Document12 pagesArbitration A Guide To International Arbitration 26050aleksandraNo ratings yet

- Leaves Room For Discretion For Nota Bene! It Looks Like TheDocument1 pageLeaves Room For Discretion For Nota Bene! It Looks Like ThealeksandraNo ratings yet

- Manual Pian 2Document16 pagesManual Pian 2aleksandraNo ratings yet

- Notes On A Method For Legal Reasoning Applied To Essay WritingDocument17 pagesNotes On A Method For Legal Reasoning Applied To Essay WritingaleksandraNo ratings yet

- Musat - Romanian Litigation-and-Arbitration PDFDocument24 pagesMusat - Romanian Litigation-and-Arbitration PDFaleksandraNo ratings yet

- Antrenament - Caiet de Lucru Al AntrenoruluiDocument134 pagesAntrenament - Caiet de Lucru Al AntrenoruluialeksandraNo ratings yet

- International Arbitral Institutions and Their Developments in Mauritius Judith LevineDocument20 pagesInternational Arbitral Institutions and Their Developments in Mauritius Judith LevinealeksandraNo ratings yet

- International Commerce ArbitrationDocument52 pagesInternational Commerce ArbitrationAangelisteNo ratings yet

- Canadian Business English Canadian 7th Edition Guffey Test Bank 1Document20 pagesCanadian Business English Canadian 7th Edition Guffey Test Bank 1tedNo ratings yet

- CONTRACT OF LEASE MangaserDocument2 pagesCONTRACT OF LEASE Mangasermary ann carreonNo ratings yet

- Divi Thilina: (Terms & Conditions Applied)Document1 pageDivi Thilina: (Terms & Conditions Applied)KetharanathanSaravananNo ratings yet

- Corporate Veil in Common LawDocument28 pagesCorporate Veil in Common LawFaisal AshfaqNo ratings yet

- Nego 11.25.23Document3 pagesNego 11.25.23Rebecca TatadNo ratings yet

- Memorandom of AssociationDocument28 pagesMemorandom of AssociationBhavani Singh RathoreNo ratings yet

- Employment ContractDocument17 pagesEmployment Contractsnelu1178No ratings yet

- 3 JRU LAW C201 - Lecture Slides With Audio - Week 03 - 2022-2023Document81 pages3 JRU LAW C201 - Lecture Slides With Audio - Week 03 - 2022-2023Jessica TalionNo ratings yet

- Transes RFBTDocument4 pagesTranses RFBTdave excelleNo ratings yet

- What Is Insurance LawDocument55 pagesWhat Is Insurance LawPulkit Mago 1703887No ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document12 pagesAssignment 1Red LionNo ratings yet

- The Oriental Insurance Company Limited: UIN: IRDAN556RP0002V01201920Document3 pagesThe Oriental Insurance Company Limited: UIN: IRDAN556RP0002V01201920Kinjal RanaNo ratings yet

- Ìnpç F,!3 "Æqè9Yî: Agent Name:-Mrs. Rekha Rani, Agent Code - 70019050, Agent Contact Number - 9829666010Document2 pagesÌnpç F,!3 "Æqè9Yî: Agent Name:-Mrs. Rekha Rani, Agent Code - 70019050, Agent Contact Number - 9829666010Mukul BajjarNo ratings yet

- TeleDirctory2004 (Big) 16 19Document47 pagesTeleDirctory2004 (Big) 16 19Sneha Roy NandiNo ratings yet

- Legal 750697 v1 IVCA Specimen ClausesDocument40 pagesLegal 750697 v1 IVCA Specimen ClausesAlexandru DumitruNo ratings yet

- QS - HM - Freight Liner Indonesia - SwakaryaDocument4 pagesQS - HM - Freight Liner Indonesia - SwakaryaAKHMAD SHOQI ALBINo ratings yet

- Projet de Contrat GeDocument13 pagesProjet de Contrat GeaboudevenomNo ratings yet

- Hanil Vs BNIDocument2 pagesHanil Vs BNIashrizas100% (1)

- Singleendment - 7-11-2023 9.12.43Document5 pagesSingleendment - 7-11-2023 9.12.43samsunggranddousromNo ratings yet

- 2004 Novatoin Definitions (Users Guide)Document32 pages2004 Novatoin Definitions (Users Guide)Michael John MarshallNo ratings yet

- Asset Transfer AgreementDocument13 pagesAsset Transfer AgreementmarindiNo ratings yet

- NORDBY CONSTRUCTION, INC. v. AMERICAN SAFETY INDEMNITY COMPANY Et Al ComplaintDocument27 pagesNORDBY CONSTRUCTION, INC. v. AMERICAN SAFETY INDEMNITY COMPANY Et Al ComplaintACELitigationWatchNo ratings yet