Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 6: Difficulties On Theory Summary and

Uploaded by

qazisafa0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

159 views3 pagesDarwin addresses some of the flaws in his theory of natural selection. He argues that natural selection requires that intermediate varieties become extinct. Darwin addresses the question of whether an intermediate species would exist in an intermediate geological area.

Original Description:

Original Title

Chapter 6: Difficulties on Theory Summary And

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentDarwin addresses some of the flaws in his theory of natural selection. He argues that natural selection requires that intermediate varieties become extinct. Darwin addresses the question of whether an intermediate species would exist in an intermediate geological area.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

159 views3 pagesChapter 6: Difficulties On Theory Summary and

Uploaded by

qazisafaDarwin addresses some of the flaws in his theory of natural selection. He argues that natural selection requires that intermediate varieties become extinct. Darwin addresses the question of whether an intermediate species would exist in an intermediate geological area.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

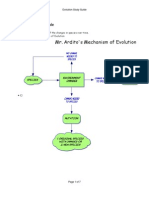

Chapter 6: Difficulties on Theory Summary and Analysis

Four objections may be raised to the theory of natural selection. The first is that, if

the species have descended from others by small, gradual changes, there should exist a large

number of intermediate, transitional organisms that link the various species together. However,

these do not exist. Second, there are many organs and traits of organisms that

seem far too complex for natural selection to produce, such as the eye, which is an

incredibly complex and fine-tuned organ. Third, how can natural selection account for the

complex instincts of animals that are often capable of producing behavior that even humans

cannot understand? Finally, according to the theory of natural selection, species

are only separated from varieties by degree of difference. However, when varieties are interbred,

the offspring is.....

Difficulties of the theory of descent with modification — Absence or rarity of transitional

varieties — Transitions in habits of life — Diversified habits in the same species — Species with

habits widely different from those of their allies — Organs of extreme perfection — Modes of

transition — Cases of difficulty — Natura non facit saltum — Organs of small importance —

Organs not in all cases absolutely perfect — The law of Unity of Type and of the Conditions of

Existence embraced by the theory of Natural Selection.

Chapter VI

Summary

Darwin addresses some of the flaws in his theory of natural selection. He tackles two major

questions: First, if species have gradually descended from other species, why do clearly defined,

separate species exist, instead of numerous intermediate forms of species? Second, can natural

selection really produce highly complex organs, such as the eye, from species lacking anything

remotely similar to such complex organs?

To answer the first question, Darwin argues that natural selection requires that intermediate

varieties become extinct. Since natural selection urges species to become perfectly adapted to

their environments, certain environments favor some characteristics and other environments

favor others, allowing species to diverge based on their separate environments. The favored

characteristics in these respective environments would become more advantageous than any

intermediate characteristics, causing the intermediate species to become extinct. Darwin

addresses the question of whether an intermediate species would exist in an intermediate

geological area between the two different environments. He argues that intermediate

environments are so geographically small that intermediate species in those areas would not be

able to reproduce sufficiently to perpetuate themselves and survive and would eventually become

extinct. Therefore, we only see small numbers of intermediate species in these intermediate

geographical zones.

Darwin is not as confident about the answer to his second question as he is about the answer to

his first. He admits that it is difficult to explain how new structures, such as the wings of a bat,

are created when a species descends from one that lacks such structures. He does give examples

from other species, in which modifications develop from existing structures instead of sprouting

anew, such as the species of flying squirrels with broad tails that allow them to parachute

through the air, a tail modified from existing tails in other squirrel species. He also explains that

scientists are unable to see a clear line of organ modification because of gaps in the development

of these structures (for example, squirrel tails that are not yet fully adapted for flying). These

gaps come about when the intermediate species have become extinct. Examples of explainable

models, such as the flying squirrel’s tail, can help an observer imagine the development of more

complex organs, such as the wings of the bat or the eye. Over time, gradual developments of

structures and nerves become more complex with modifications, until finally the most perfect

eye organ develops. Darwin compares the eye to a telescope: Over time and through its

development, the telescope has become more and more advanced, replacing older versions.

While the mechanism of change for the telescope is technological advancement, for the eye it is

natural selection.

Darwin also discusses the existence of undeveloped and useless organs. In contrast to highly

complex organs that are clearly products of natural selection, undeveloped and useless organs

indicate that some traits might have been advantageous at one point and eventually waned in

importance over time. Primarily, Darwin argues that science cannot always assume the

importance or unimportance of a particular variation. Some organs, transmitted to a species but

useless to it, may have been useful to a distant ancestor. Moreover, some modifications that seem

important to us may not be important at all. For example, if only green woodpeckers existed,

scientists would assume that the color green was important to the woodpecker’s survival.

However, many different colors of woodpeckers exist, so color must be a result of sexual

selection, which is relatively unimportant for species’ survival. The perpetuation of useless or

random variations illustrates one of the principles of natural selection: that selection of

advantageous characteristics makes a species better than those before it but does not create

immediate perfection in a species. Leftover characteristics may remain, as long as they cause no

harm to the species. Ultimately, these leftover characteristics serve as reminders of the very

slightness of change that occurred by natural selection over time. The goal of natural selection is

to make each species better, not to produce perfection right away. Only over time do species

become perfectly adapted to their environments.

Analysis

In attempting to address some of the gaps in his theory of natural selection, Darwin once again

shows the power of inductive reasoning. He acknowledges the unknowns inherent in his own

theory and accepts that he simply cannot answer certain questions, such as how a bat develops its

wings or how the eye develops its immensely complex structure. However, by using examples

that demonstrate how modification might occur in some species, Darwin creates principles of

modification that can be applied to the development of other species, even if he can’t explicitly

prove that the principles hold true for these particular species. This is precisely how scientific

theories develop—through the creation of models that can be applied to similar situations. In

Chapter VI, Darwin highlights the uncertainty inherent in scientific theorizing and the inductive

reasoning and modeling that allow theories to survive despite these uncertainties.

By defending his theory with inductive reasoning, Darwin once again implicitly attacks natural

theologians who believe that the complex structure of each species proves that God created them

independently. Darwin’s comparison of the eye to a telescope singles out natural theologian

William Paley, who used the telescope analogy to suggest that God reveals his plan in the

complexity and purpose of the organs he designs. Darwin turns the telescope example on its

head. He asks, If millions of years of modification have shaped the eye to its perfected state,

could the eye be even more perfect than the telescope? And doesn’t the perfection of the eye

show the power of natural selection, regardless of whether God or nature controls the process?

Darwin challenges natural theology on its own terms. He argues that natural selection provides

the requisite explanations for the development of species. He also acknowledges the brilliance of

creation, leaving room for God in the theory of natural selection.

Darwin’s discussion of the imperfections of natural selection provides insight into the

relationship between natural selection and progress. Although natural selection does not

automatically create perfectly adapted species, it never chooses characteristics that injure the

species and leave it with less of a chance for survival. Therefore, natural selection ensures that

each species improves, rather than worsens, in comparison to its ancestors. Progress always

creates a better natural society for all species, even though they develop individually. Social

theorists later utilized Darwin’s theory of natural selection to account for social progress. They

asked whether society always progresses in an upward trend, getting better and more advanced,

or if it was it possible for society to degenerate. Although Darwin argues that progress is always

positive as a result of natural selection, some social theorists argued that society could

degenerate with the rise of poverty and crime.

You might also like

- The Edge of Evolution: The Search for the Limits of DarwinismFrom EverandThe Edge of Evolution: The Search for the Limits of DarwinismRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (8)

- Earth and Life Science Q2 Module 8 EvolutionDocument19 pagesEarth and Life Science Q2 Module 8 EvolutionMarc Joseph NillasNo ratings yet

- TOEFL ReadingDocument7 pagesTOEFL ReadingMaria OrlovaNo ratings yet

- Artigo 3 - MestradoDocument10 pagesArtigo 3 - MestradoThiago RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Reading Practice Test 1Document11 pagesReading Practice Test 1claraNo ratings yet

- Five Questions EvDocument7 pagesFive Questions EvIgor de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- 0 Chapter 22 Darwin Reading Guide AnswerDocument6 pages0 Chapter 22 Darwin Reading Guide AnswerKatherine ChristinaNo ratings yet

- FinalExam - Biology2Document2 pagesFinalExam - Biology2Ken AmorinNo ratings yet

- Ch22 Decent With Modification A Darwinian View of LifeDocument4 pagesCh22 Decent With Modification A Darwinian View of LifeAdamSalazarNo ratings yet

- Evolution Station Cards BIOLOGY COMPLETE WORSHEET ASSIGNMENT ANSWERSDocument7 pagesEvolution Station Cards BIOLOGY COMPLETE WORSHEET ASSIGNMENT ANSWERShenry bhoneNo ratings yet

- EvolutionDocument5 pagesEvolutionAshwarya ChandNo ratings yet

- 1614067948TOEFL Reading Practice Set 5Document5 pages1614067948TOEFL Reading Practice Set 5Ojaswa PathakNo ratings yet

- Chapter 22 HomeworkDocument2 pagesChapter 22 Homeworkasdfasdaa100% (1)

- Bio ProjectDocument12 pagesBio ProjectCadine DavisNo ratings yet

- Reading Practice 2Document2 pagesReading Practice 2Fadhila SyarifatunNo ratings yet

- G-12 Biology, 4.2 Theories of EvolutionDocument4 pagesG-12 Biology, 4.2 Theories of EvolutionYohannes NigussieNo ratings yet

- Reading Passage 1 - DarwinDocument5 pagesReading Passage 1 - DarwinAya HelmyNo ratings yet

- Las 8 Bio2 PDFDocument12 pagesLas 8 Bio2 PDFPeanut BlobNo ratings yet

- Cassification of Living ThingsDocument11 pagesCassification of Living ThingsFidia Diah AyuniNo ratings yet

- EvolutionDocument41 pagesEvolutionSophia NevalgaNo ratings yet

- Proof of Life - How Would We Recognize An Alien If We Saw One - Reader ViewDocument3 pagesProof of Life - How Would We Recognize An Alien If We Saw One - Reader ViewBlazing BooksNo ratings yet

- SPECIALIZED 12 GenBio2 Semester-II CLAS4 Evidence-of-Evolution v4 FOR-QA-carissa-calalinDocument15 pagesSPECIALIZED 12 GenBio2 Semester-II CLAS4 Evidence-of-Evolution v4 FOR-QA-carissa-calalinZyrichNo ratings yet

- Chapter-3: Evolution and Origin of LifeDocument23 pagesChapter-3: Evolution and Origin of Lifesanjit0907_982377739No ratings yet

- Evo Bio Midterm NotesDocument21 pagesEvo Bio Midterm NotesShareeze GomezNo ratings yet

- Evolution Close ReadingDocument2 pagesEvolution Close Readingapi-377700100100% (1)

- Darwin's TheoryDocument7 pagesDarwin's TheoryAbdelrahman MohamedNo ratings yet

- Debunking Misconceptions Regarding The Theory of EvolutionDocument5 pagesDebunking Misconceptions Regarding The Theory of Evolutionapi-350925704No ratings yet

- S10 Q3 Enhanced Hybrid Module 6 Week 6 FinalDocument15 pagesS10 Q3 Enhanced Hybrid Module 6 Week 6 Finalace fuentesNo ratings yet

- Biology Review NotesDocument11 pagesBiology Review NotesRoyals Radio100% (1)

- Presentation About EvolutionDocument20 pagesPresentation About EvolutionHizzei CaballeroNo ratings yet

- CompApps For Word Tut 2Document7 pagesCompApps For Word Tut 2ca8paul14No ratings yet

- Iodiversity and VolutionDocument36 pagesIodiversity and VolutionMayden Grace Tumagan GayatgayNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Guided NotesDocument5 pagesUnit 1 Guided Notesapi-280725048No ratings yet

- Evolution: Evolution (Also Known As Biological, Genetic or Organic Evolution) Is The Change inDocument3 pagesEvolution: Evolution (Also Known As Biological, Genetic or Organic Evolution) Is The Change inJa VizcarraNo ratings yet

- Natural SelectionDocument81 pagesNatural Selectionpatricia piliNo ratings yet

- S Announcement 28055Document115 pagesS Announcement 28055patricia piliNo ratings yet

- Kebutuhan Hara Bagi TumbuhanDocument2 pagesKebutuhan Hara Bagi TumbuhanHamdan FatahNo ratings yet

- Evolutionary Theory Project EssayDocument5 pagesEvolutionary Theory Project Essayapi-317556860No ratings yet

- Biology M15 EvolutionDocument25 pagesBiology M15 EvolutionDiana Dealino-Sabandal0% (2)

- Thomas Winterbottom: Darwins Theory of Evolution: A New CritiqueDocument23 pagesThomas Winterbottom: Darwins Theory of Evolution: A New CritiqueThomas F. WinterbottomNo ratings yet

- Deepak Chopra - Intelligent DesignDocument3 pagesDeepak Chopra - Intelligent Designralucutza7100% (1)

- 16.3 Darwin Presents His CaseDocument25 pages16.3 Darwin Presents His CaseAlex BeilmanNo ratings yet

- Natural Selection SlidesDocument34 pagesNatural Selection Slidesapi-283801432No ratings yet

- B C Goodwin InterviewDocument6 pagesB C Goodwin InterviewAgustina Verde MusgoNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument6 pagesUntitledNicole PauigNo ratings yet

- Evolution Study GuideDocument7 pagesEvolution Study Guidegmanb5100% (3)

- Why Life Does Not Really ExistDocument5 pagesWhy Life Does Not Really Existrbenit688062No ratings yet

- Evolution Test Review KeyDocument5 pagesEvolution Test Review Keyapi-242868690No ratings yet

- Does Refuting The Darwinian Theory of Evolution Imply Refuting Animal and Plant Evolution?Document5 pagesDoes Refuting The Darwinian Theory of Evolution Imply Refuting Animal and Plant Evolution?Khan SabNo ratings yet

- Dissection LabDocument13 pagesDissection LabKaliyah LynchNo ratings yet

- Reading Guide For Charles Darwin, On The Origin of Species, 1st EditionDocument6 pagesReading Guide For Charles Darwin, On The Origin of Species, 1st Editionb8245747No ratings yet

- Essay Evolution 20230317Document4 pagesEssay Evolution 20230317ianNo ratings yet

- Darwin and Lamarck Readings PDFDocument2 pagesDarwin and Lamarck Readings PDFZhiyong HuangNo ratings yet

- Bio120 NotesDocument3 pagesBio120 Notesyusrawasim147No ratings yet

- The Theory of EvolutionDocument9 pagesThe Theory of EvolutionElana SokalNo ratings yet

- Natural Selection Research Paper TopicsDocument4 pagesNatural Selection Research Paper Topicsgz7veyrh100% (3)

- 4-5-2021 DarwinDocument4 pages4-5-2021 DarwinHaris KhanNo ratings yet

- Pagel 2009 - Natural Selection 150 Years OnDocument4 pagesPagel 2009 - Natural Selection 150 Years OnCamilo GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Nama: Citra Ariza 1911060269 Dwi Rahma Pelita 1911060286 Kelas: Biologi 4DDocument7 pagesNama: Citra Ariza 1911060269 Dwi Rahma Pelita 1911060286 Kelas: Biologi 4Ddwi rahmaNo ratings yet

- Phonetics and Phonology: Maam Mehak Munawer HOD Language and Literature Hajvery University (HU)Document26 pagesPhonetics and Phonology: Maam Mehak Munawer HOD Language and Literature Hajvery University (HU)Zainab Ajmal ZiaNo ratings yet

- Of The Sublime Presence in QuestionDocument263 pagesOf The Sublime Presence in QuestionMax GreenNo ratings yet

- Unit5 EmployementDocument13 pagesUnit5 EmployementRabah É Echraf IsmaenNo ratings yet

- Image Segmentation: FemurDocument18 pagesImage Segmentation: FemurBoobalan RNo ratings yet

- Course Outline Accounting ResearchDocument12 pagesCourse Outline Accounting Researchapi-226306965No ratings yet

- A Comparative GrammarDocument503 pagesA Comparative GrammarXweuis Hekuos KweNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion Reflection - AdvocacyDocument2 pagesHealth Promotion Reflection - Advocacyapi-242256654No ratings yet

- Learners With Difficulty in Basic Learning and Applying Knowledge Grade 6 and SHSDocument74 pagesLearners With Difficulty in Basic Learning and Applying Knowledge Grade 6 and SHSChristian AguirreNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka: Bilingualism. Carlton: Blackwell Publishing LTDDocument6 pagesDaftar Pustaka: Bilingualism. Carlton: Blackwell Publishing LTDAnna Tsuraya PratiwiNo ratings yet

- English Lesson Plan in 4 Types of Sentences by JauganDocument5 pagesEnglish Lesson Plan in 4 Types of Sentences by JauganMarlon JauganNo ratings yet

- Lev Vygotsky's Social Development TheoryDocument24 pagesLev Vygotsky's Social Development TheoryNazlınur GöktürkNo ratings yet

- Writing Conventions - PretestDocument3 pagesWriting Conventions - PretestDarkeryNo ratings yet

- Module 3 CT AssignmentDocument3 pagesModule 3 CT Assignmentapi-446537912No ratings yet

- Because or Due ToDocument9 pagesBecause or Due ToJiab PaodermNo ratings yet

- Navigate Pre-Intermediate Wordlist Unit 3Document2 pagesNavigate Pre-Intermediate Wordlist Unit 3DescargadorxdNo ratings yet

- Normalization Questions With AnswersDocument6 pagesNormalization Questions With Answerspoker83% (29)

- Grammar QuizDocument27 pagesGrammar QuizFJ Marzado Sta MariaNo ratings yet

- Accommodation Patterns in Interactions Between Native and Non-Native Speakers - PortfolioDocument20 pagesAccommodation Patterns in Interactions Between Native and Non-Native Speakers - Portfolioapi-201107267No ratings yet

- Evans v. Dooley J. New Round Up 5 Students Book 2011 p208Document1 pageEvans v. Dooley J. New Round Up 5 Students Book 2011 p208Alex RoznoNo ratings yet

- HCD-Research in AI 1.33Document20 pagesHCD-Research in AI 1.33Tequila ChanNo ratings yet

- Social Media FinalDocument5 pagesSocial Media Finalapi-303081310No ratings yet

- Rynna's Week 13 TSL1044 Online Learning 2 Part 1Document2 pagesRynna's Week 13 TSL1044 Online Learning 2 Part 1Rynna NaaNo ratings yet

- G5. Improvisation in Various Art FormsDocument21 pagesG5. Improvisation in Various Art FormsEa YangNo ratings yet

- Unit 11, Unit 12, Unit 13, and Unit 14Document4 pagesUnit 11, Unit 12, Unit 13, and Unit 14ronnie jackNo ratings yet

- Looking at Aspects of A NovelDocument17 pagesLooking at Aspects of A NovelGus LionsNo ratings yet

- Debate THBT Technology Decreases Creativity Online 2020Document5 pagesDebate THBT Technology Decreases Creativity Online 2020kbr8246No ratings yet

- Language and Political EconomyDocument24 pagesLanguage and Political EconomygrishasNo ratings yet

- Higher Care - Unit 2 - Sociology For CareDocument165 pagesHigher Care - Unit 2 - Sociology For CareJen88% (8)

- Sse Gaeilge Improvement Plan SummaryDocument3 pagesSse Gaeilge Improvement Plan Summaryapi-243058817No ratings yet

- Dimension of Literary TextDocument11 pagesDimension of Literary TextMarian FiguracionNo ratings yet