Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Factors Which Contributed To The Reduction of Torture in The Thai Criminal Justice System 1983-2007

Uploaded by

ICGPOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Factors Which Contributed To The Reduction of Torture in The Thai Criminal Justice System 1983-2007

Uploaded by

ICGPCopyright:

Available Formats

1st International Conference on Government and Politics

March 20, 2015, Rangsit University, Thailand

Factors which Contributed to the Reduction of Torture

in the Thai Criminal Justice System 1983-2007

Richard F. Lancaster*

Abstract

The reduction of the use of torture in a criminal justice system must be a priority for creating justice,

with developing nations particularly struggling with the use of interrogational torture. This research addressed

what social, economic, political and legal factors have affected the reduction of torture in democratic Thailand

with a view to informing policy and legislation to maintain the standards of the United Nations Convention

Against Torture. It was found, through comparing existing literature in the field of torture to sources on modern

Thai political, legal, social and economic events and changes, that many social and economic factors have

contributed to the reduction in the prevalence of torture. However some important governmental policies and

police reforms must still be made. Further improvements at this stage are largely hindered by low financial

resources to the police and other relevant bodies and high levels of corruption within the criminal justice

system resulting in low rates of prosecution for torture. Whilst democracy has often been interrupted and

flawed, there is high social participation and there have been improvements in the human rights focus of

constitutions.

Keyword: Torture, Thai Royal Police, Police, Thailand, Criminal Justice

Introduction

Torture is widely recognised as one of the most personally and socially damaging actions of

government, in the words of Danner (2012), Torture is the ultimate destruction, by the state, of human

autonomy. Whilst international law and conventions, including the Convention against Torture and Other

Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) (UN General Assembly, 1984), expressly

prohibit torture, it remains a prominent technique in the Criminal Justice Systems of developing nations. It is

obvious that international law alone cannot significantly reduce the use of torture. Therefore, we must consider

what has been effective in the past, in order to design a torture-free future. This paper will consider a case

study of the Thai criminal justice system between 1983 and 2007 and discuss what social, economic,

political and legal events and changes have contributed to the reduction of the use of torture by the Royal Thai

Police force. Whilst there is much existing literature which states possible methods for reducing torture within

*

Graduate School of Peace and Diplomacy, Siam University; Email: r.f.lancaster88@gmail.com

1st International Conference on Government and Politics

March 20, 2015, Rangsit University, Thailand

a criminal justice system, many of these methods involve intensive reforms of police procedure, monitoring

and investigation methods, which require high levels of state investment in the criminal justice system, or

suggests a zero tolerance policy on the prosecution of officials who have been accused of torture, which could

be considered overly idealistic in criminal justice systems with high levels of corruption. Whilst these existing

theoretical models may be somewhat out of reach of developing nations, the existing research does raise the

question of how can theory pertaining to the reduction of torture be viewed through the needs and abilities of

the developing world. This research hypothesises that: Certain sub-factors within social, economic, political

and legal development will be of great significance in the natural reduction of torture in a criminal justice

system.

This research will consider the case of the Kingdom of Thailand. Many sources have discussed that

the use of torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment has been steadily reducing within the Thai

criminal justice system since the 1970s (U.S. Department of State, 1989). This research will cover the

timescale of 1983-2007, falling between the end of long term military rule in Thailand and the Thai

government ratifying the Convention against Torture. The kingdom of Thailand is a useful case to research for

many reasons, including its current attempts to create legislation which will make torture a criminal offence.

Torture comes in many forms. For the purpose of this research the term torture will be defined as in

Article 1 of the CAT (UN General Assembly, 1984). The CAT defines torture through intent rather than specific

actions and confines this definition to torture committed by, or at the request of state officials. The question

of this research extends only to the criminal justice system, therefore, for this research will only consider

torture committed by police officers and correctional officers within the penal system.

A key limitation of this study is the sensitive nature of its topic. Torture is a highly sensitive issue and

with its criminal implications and power over public opinion with regards to political regimes, discussion and

information regarding practices of torture in Thailand will not be as available as would be liked, this lack of

availability will be increased due to heavy censorship of the media and internet within Thailand.

Methods

The central discussion of this paper will be secondary research. A review and discussion of existing

literature and theory on the subject of torture will be analysed and compared against sources discussing

events and changes in Thai history from 1983 to 2007 to find what existing literature and theory suggests

are the most significant events and changes in the case of Thailand.

Findings

This section will outline the main theory in existing literature on torture in the four main factors as

they will be discussed: Social factors, Economic factors, Political factors and Legal factors.

Bennett et al (2006) state that to combat torture an open national debate must be created fostering

opposing points of view. Becker (2004) suggests that authoritarian governments may try to restrict or

dissuade criticism of state actions.

[12]

1st International Conference on Government and Politics

March 20, 2015, Rangsit University, Thailand

Wu and Vander Beken (2010) discuss that traditional Asian cultures place a priority on collective

good, which can be at odds which can conflict with protection of human rights.

Lianos (2013) suggests that in certain circumstances public opinion may sway politicians to

diminish personal rights.

Wu and Vander Beken (2010) state that certain socio-economic groups, particularly poor, transient

urban workers and migrant workers are at increased risk of torture.

Barrett & Rudgard (2014) discuss that when regional police departments are better funded they will

be more capable of implementing reforms and increasing staff numbers which will help to prevent torture.

Miller (2011) states that with economic growth comes a philosophy of post-materialism and greater

social focus on human rights. Miller (2011) continues by discussing that higher levels of economic

globalisation lead to a greater respect for international human rights norms due to greater interdependence of

governments.

Becker (2010) states that hierarchical governments have a greater capacity for internal scrutiny and

accountability.

Wu and Vander Beken (2010) suggest that if police institutions are not independent of government

they can be subject to pressures to reduce crime rates and solve crimes which can increase the possibility of

torture. They continue by discussing that a greater focus on physical evidence methods of investigation can

reduce the need for a confession and thus reduce the possibility of torture.

Miller (2011) states that democracy is a key factor in reducing torture as it makes governments

publically accountable, however, Fein (1995) suggested that there are often greater levels of personal rights

violations in transitional democracies than in authoritarian states.

Rafiqul and Solaiman (2003) state that constitutions are the means by which a state insures the

rights of its citizens and that once the state has made these declarations the state can be held accountable

for infringements of these rights.

Mayerfeld (2007) discussed that Reservations, Understandings and Declarations, tools used by

governments to limit the extent to which they must abide by international treaties and conventions, are highly

detrimental to the protection of human rights.

Rafiqul and Solaiman (2003) state that governmental transparency is of great importance in allowing

public scrutiny.

Schabas (2007) discusses that there are numerous benefits of diplomatic relationships with other

nations such as support and collaborative programs to combat torture and reform criminal justice systems.

Costanzo and Gerrity (2009) state that when governments are caught violating human rights they

may use techniques such as demonising victims to prevent criticism and maintain public support.

Becker (2010) discusses the importance of selecting judges who are above corruption and have no

connection with the case so as to prevent bias.

Mujuzi (2013) states that it is of great importance to ensure that no evidence obtained as a result

of torture may be allowed in court, to the extent that the burden of proof is on the state to prove that torture

was not performed.

[13]

1st International Conference on Government and Politics

March 20, 2015, Rangsit University, Thailand

Discussion

The discussion of the theory in existing literature will be followed in the same sequence of the four

main factors: Social factors, Economic factors, Political factors, Legal factors.

Thailand has a long history of media censorship, whilst both the 1997 and 2007 constitutions

protect freedom of speech and a free press (Constitution Drafting Commission, 2007), however, these

protections are conditional and the conditions have been used by successive governments to control, censor

and intimidate media organisations.

Despite this history of censorship there have been improvements in the freedom of Thai media

outfits. The periods of strict censorship, although some occurring very recently are largely associated with

individual governments, particularly military governments, for example the military regime in 2007

implemented the Computer-Related Crimes Act, strictly restricting web usage. In the last decade there has

been an increase in the prevalence of unlicensed local community radio stations (Siriyuvasak, 2002), these

stations are rarely censored and attempts to censor in the past have resulted in a public backlash and

accusations of state authoritarianism (Rojanaphruk, 2005). Article 47 of the 2007 constitution (Constitution

Drafting Commission, 2007) protects a communitys right to this independent radio broadcasting.

In communitarian societies, such as Thailand, there is a personal responsibility to confess

wrongdoings; this may undermine the right to silence in criminal proceedings by allowing interrogators to

coerce confessions if they feel suspects are withholding information (Wu & Vander Beken, 2010).

Komin (1990) discusses the relative social values in Thai culture. It was found that Thai culture

displays a variety of values pertaining to social interdependence. It was also found that Ego orientation whilst

the number one value across Thailand (reflecting non-communal values) it is much less prominent among

farmers and rural communities thus showing a development from a traditional communal society to a more

globalised individualist society, and with these communities already being at greater risk of torture this low

valuing of ego and individuality increases that risk.

Internet access and usage in Thailand has increased considerably since adoption in 1996. This can

be considered in part due to improvements in service quality and decrease in price, but it also shows a great

deal of modernisation within Thailand.

Thailand has a good example of public opinion regarding crime and draconian crime prevention in

recent history. In 2003 Thaksins Drug War resulted in the deaths of an estimated 2,275 people

(Dabhoiwala, n.d.). Drug use in Thailand, especially the use of yaabaa, is considered one of the most severe

social issues in modern times. Making attempts to combat this problem is a key part of any Thai

governments legitimacy. In 2005 a study by ABAC University found that 74% of 5,168 respondents

supported former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatras war on drugs ("Public Senses", 2005) despite

condemnation from the UN and many NGOs for its high death toll and authoritarian police powers. This shows

that in Thailand there may be high public support for extreme measures to combat crime. It is important to

note however, that media and official government reports stated that very few of the deaths were caused by

police directly; this may have influenced public opinion.

Gross domestic product (GDP) allows an overview of a countrys economy. We can see from

Thailands GPD over time that there has been an economic boom over the timescale of this research.

[14]

1st International Conference on Government and Politics

March 20, 2015, Rangsit University, Thailand

Thailands GDP quadrupled between 1980 and 1997 before suffering a severe recession in the late 1990s

and early 2000s and returning to slightly above pre-recession levels in 2007. This economic development

reflects development in a range of fields, as shown through the strong correlation between GPD and the

Human Development Index (HDI) and can be seen as contributing to the reduction of torture through

increased state budgets to improve police resources and other public services discussed in this research.

Migrant workers around the world are particularly vulnerable to exploitation due to their fragile social

status, with many cases in Thailand linked to human trafficking of, mostly Myanmar, migrants. The total

numbers of migrant workers in Thailand has been rising steadily for several decades, from 700,000 in 1995

to 1,773,349 in 2005 (Pholphirul & Rukumnuyakit, n.d.). These migrant workers do not receive the same

entitlement to minimum wage as Thai workers and often are poorly educated. This combined with a lack of

social security make migrant workers vulnerable to many forms of abuse, including torture.

The development of a post-materialist culture in modern Thailand is apparent. Whilst much research

discusses strong materialist values in modern Thai society, this is not related to concrete needs such as food

and shelter, but rather status symbols such as designer clothing and luxury goods. However it can be seen

that modern Thai society places a high importance on abstract needs such as freedom, equality and human

dignity, this is evident through the high level of political activism in Thailand throughout the 21st century, with

several extended mass rallies focused on poor government responses to social issues or allegations of

corruption.

Pathmanand (2001), discussed the recent history of economic globalisation and its effects on Thai

society in detail. It was found that in the early to mid-1990s economic liberation allowed high levels of

foreign investment and loss of economic sovereignty to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) before the

impacts of the Asian financial crisis in 1997-98. It was also discussed that this global integration brought

with it stronger principles of human rights and greater demand for democracy.

We can see from this governmental structure in executive, legislative and judicial arms there is a

highly evolved hierarchical structure in which bodies and individuals oversee the actions of one another to

provide the checks and balances necessary for reducing torture. Also with the hierarchical structure of the

courts, accusations of torture can be followed through the appeals court and Supreme Court independent of

those involved with the original trials and if necessary encountering reputable judges who have sufficient

career development and power to not only be sufficiently ethically guided, but also distanced from corruption

to seek justice if lesser courts have failed. Indeed the Supreme Court scheduled to hear an appeal on the

Takbai inquest.

The police in Thailand are not politically independent. Since 1998 they have been under the direct

control of the Prime Minister, and previously under the control of the Ministry of the Interior. There have been

many allegations of the Thai police force acting as political enforcers, with the Prime Minister having the

power to choose a police general and Justice and Interior ministers sitting on the Board of the Royal Thai

Police and the eagerness to meet politically motivated quotas, notably in Thaksins drug war in which an

estimated 2,275 civilians were killed. Dabhoiwala (n.d.) suggested that these deaths were largely due to the

high quotas implemented on police. There is no external monitoring of police activities. This allows police to

act as they wish and allows corruption to influence internal investigations.

[15]

1st International Conference on Government and Politics

March 20, 2015, Rangsit University, Thailand

Winijkulchai and McQuay (2013) note that the use of forensic science by the Thai Royal Police has been

constrained by a lack of qualified professionals and a lack of resources due to low police budgets. There are

also problems with contradictions and gaps in the legal and regulatory regime governing the application of

forensic science and the limited communication and coordination among forensic specialists.

It is widely acknowledged that low level corruption is rife within the Thai Royal Police force. This

shows a failure on the part of the Thai government to implement policy which effectively curbs corruption and

criminal misconduct within the Thai Royal Police force.

The history of Thai democracy is spotted with coup dtats, military rule, unelected civilian rulers,

protests and allegations of corruption. The prevalence of coup dtats in Thai history is of particular

importance as these re-start attempts at democracy, essentially perpetuating the transition into democracy.

There have been 21 attempted or successful coups since 1900.

Many INGOs work observing, researching and assisting with operations to promote respect for human

rights within Thailand, including, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and the Asia Foundation.

Alongside these organisations there are independent government agencies such as the National AntiCorruption Commission and the Ombudsmen which have powers to investigate and press charges for

corruption and the Human Rights Commission of Thailand which oversees and reports on human rights

violations in Thailand and the regional ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights. All of these

independent, non-governmental or regional organisations working in tandem provides adequate separation of

powers to create the foundation for improving human rights in Thailand.

Section 32 of the 2007 constitution of Thailand (Constitution Drafting Commission, 2007) states

that A person shall enjoy the right and liberty in his or her life and person. A torture, brutal act, or

punishment by a cruel or inhumane means shall not be permitted. Section 257 of the 2007 constitution of

Thailand lays out the powers and duties of the National Human Rights Commission (Constitution Drafting

Commission, 2007), including to examine and report human rights abuses or actions which break

international treaties, propose solutions to appropriate bodies when these abuses occur and refer to the

National Assembly if action is not taken, to refer cases to the Constitutional Court when necessary or file

lawsuits to the Court of Justice on behalf of individuals.

Thailand has used RUDs to limit its commitment to some treaties, including the International

Covenant for Civil and Political Rights and the CAT, including exemption from article 30 which allows states to

submit to arbitration in an international disagreement of the interpretation or application of the convention.

The Official Information Act of 1997 ("Official Information", 1997) gives public access to almost all

government data, and if access is refused by the state, the case can be appealed to the Official Information

Commission (OIC). Whilst this Act has been popular with the Thai public there have been problems with

implementation, largely surrounding a lack of understanding on the part of both the public and state officials

as to the procedures for requesting or publishing information respectively.

Repeated coups and periods of military rule have also bought criticism from western nations,

including the suspension of a US funded military training program pending a return to civilian rule in the most

recent 2014 coup dtat. This prevents a consistent building of diplomatic relations with other nations.

Another side of diplomatic relations and human rights is Thaksin Shinawatra and successive military regimes

support of the Junta in Myanmar despite a widely criticised human rights record. Whilst ASEAN has a human

[16]

1st International Conference on Government and Politics

March 20, 2015, Rangsit University, Thailand

rights declaration it has been criticised as it is not legally binding and is unenforceable due to a lack of a

regional court to try cases.

Whilst Thaksins drug war mainly resulted in a high death toll as with the Takbai incident, the

extended military action in the southern provinces routinely uses torture which must be justified to the public

and the international community. In all of these cases officials including the Prime Minister attempted to

demonise their opponents. Referring to the drug dealers being killed in the drug war Prime Minister Thaksin

said [Murder] is not an unusual fate for wicked people (Dabhoiwala, n.d.).

Farrell (2007) discusses the views of the Thai judiciary regarding allegations of torture. Suggesting

that judges are legally protected from criticism and that an ends justify the means approach allows torture to

go on unopposed, particularly in high profile cases. Warsta (2004) discusses corruption in Thailand and

states that whilst judges are generally considered honest, 30% of defendants are asked for bribes, this

shows a clear pervasiveness of corruption and bias within the Thai judiciary, who also discusses that these

bribes are often taken through an intermediary rather than by the judge themselves, this utilises a loophole in

current legislation preventing prosecution.

Evidence, including a confession, can be dismissed from court if it was obtained in a way which is

thought to have violated the defendants rights under the constitution (including torture). Section 57 of the

CPC states that an individual may only be arrested, detained or imprisoned when a warrant is produced.

Section 78 provides strict guidelines for arrest without a warrant, which can only be practiced in 4 clearly

defined situations. The CPC also provides adequate guidelines for access to and provision of legal counsel.

Other important points of the CPC and other legislation relevant to torture within the criminal justice system

have been discussed at other points within this research.

Section 35 of the 2007 Constitution of Thailand (Constitution Drafting Commission, 2007) is concerned

with the protection of privacy, extends this constitutional protection against the circulation of information which

violates or affects a persons family rights, dignity, reputation or the right of privacy. This constitutional

protection has been used to prosecute victims of torture for their accusations of officials.

Conclusion

It is apparent from this research that there is a high level of interdependence between the factors

and subfactors discussed with the cumulative effects of all reducing the use of torture in the Thai criminal

justice system.

It has been discussed in much existing research that there are 3 central means: Training of officers,

the allowance of visitation of places of detention and investigation and prosecution of torturers. Whilst

progress has been made in these areas, improvements can still be made, particularly in the area of ensuring

thorough and independent investigations of all allegations of torture.

This research has identified the areas in which Thailand has, either directly or indirectly, reduced the

use of torture within its criminal justice system and identified areas which still cause problems and must be

improved. The further reduction and eventual elimination of torture within the Thai criminal justice system are

of the greatest importance, to abide by international law and the CAT and to ensure the protection of the

[17]

1st International Conference on Government and Politics

March 20, 2015, Rangsit University, Thailand

safety, security and liberty of all Thai citizens. This research may be used to inform the discussion of domestic

policy and of the pending legislation to criminalise torture in Thailand.

References

Barrett, D., Rudgard, O. 2014. Taxpayer Picks Up Bill for Hundreds of Police Officers Signed Off With Stress.

Retrieved September 2 2014 from www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/law-and-order/10625003

/Taxpayer-picks-up-bill-for-hundreds-of-police-officers-signed-off-with-stress.html.

Becker, S. W. 2010. When Judges Judge Themselves: The Chicago Police Torture Scandal and the

Continuing Quest for Justice in the Case of People v Keith Walker. DePaul Journal for Social Justice

3 (2): 115-137.

Constitution Drafting Commission 2007. Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand B.E. 2550. Retrieved from:

english.constitutionalcourt.or.th/index.php?option=com_docman&Itemid=4&lang=en.

Costanzo, M. A., Gerrity, E. 2009. The Effects and Effectiveness of Using Torture as an Interrogation Device:

Using Research to Inform the Policy Debate. Social Issues and Policy Review 3 (1): 179-210.

Dabhoiwala, M. n.d.. A Chronology of Thailand's "War on Drugs". Retrieved September 4 2014 from: www.

humanrights.asia/resources/journals-magazines/article2/0203/a-chronology-of-thailands-waron-drugs.

Farrell, J. A. 2007. Something Rotten: Tortured Confessions. Retrieved September 6 2014 from: www.chiang

mainews.com/indepth/details.php?id=2019

Fein, H. 1995. More Murder in the Middle: Life-Integrity Violations and Democracy in the World 1987.

Human Rights Quarterly 17 (1): 170-191.

Komin, S. 1990. Culture and Work Related Values in Thai Organisations. International Journal of Psychology

25: 681-708.

Lianos, M. 2013. Dangerous Others, Insecure Societies: Fear and Social Division. Retrieved September 22

2014 from: www.ashgate.com/isbn/9781409443995

Mayerfeld, J. 2007. Playing by Our Own Rules: How U.S. Marginalization of Human Rights Law Led to

Torture. Harvard Human Rights Journal 20: 89-140.

Miller: 2011. Torture Approval in Comparative Perspective. Human Rights Review 12: 441-463.

Mujuzi, J. D. 2013. The African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights and the admissibility of evidence

obtained as a result of torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment: Egyptian Initiative for

Personal Rights and Interights v Arab Republic of Egypt. The International Journal of Evidence & Proof

17: 284-294.

"Official Information". 1997. Official Information Act B.E. 2540. Retrieved September 1 2014 from: www.oic.

go.th/content/act/act2540eng.pdf

Pathmanand, U. 2001. Globalisation and Democratic Development in Thailand: The New Path of the Military,

Private Sector, and Civil Society. Retrieved September 15 2014 from: www.gsdrc.org/go/display&

type=Document&id=5044

[18]

1st International Conference on Government and Politics

March 20, 2015, Rangsit University, Thailand

Pholphirul, P., Rukumnuyakit: n.d.. Economic Contribution of Migrant Workers to Thailand. Retrieved April 10

2014 from: news.nida.ac.th/th/images/PDF/article2551/%E0%B8%AD.%E0%B8%9E%E0%B8%B

4%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%B4%E0%B8%A2%E0%B8%B0.pdf.

Public Senses. 2005. Public Senses War on Drugs Futile. Bangkok Post. Retrieved February 26 2014

from: www.mapinc.org/newscsdp/v05/n471/a09.html

Rafiqul, M., Solaiman, S. M. 2003. Torture under Police Remand in Bangladesh: A Culture of Impunity for

Gross Violations of Human Rights. Asia-Pacific Journal on Human Rights and the Law 2: 1-27.

Rojanaphruk: 2005. Community-Radio Crackdown Planned. The Nation Retrieved May 8 2014 from: www.

nationmultimedia.com/2005/06/01/national/data/national_17552513.html

Schabas, W. A. 2007. House of Lords Prohibits Use of Torture Evidence, but Fails to Condemn Its Use by

the Police. International Criminal Law Review 7: 133-142.

Siriyuvasak, U. 2002. Community Radio Movement: Towards Reforming the Broadcast Media in Thailand.

Retrieved June 18 2014 from: www.freedom.commarts.chula.ac.th/articles/MRSU02-Community_

radio.pdf.

Thailand Internet. 2014. Thailand Internet User. Retrieved September 2 2014 from: internet.nectec.or.th/web

stats/internetuser.iir?Sec=internetuser.

UN General Assembly. 1984. Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or

Punishment.

U.S. Department of State. 1989. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 1988. Retrieved September

21 2013 from archive.org/stream/countryreportson1988unit#page/n1/mode/2up.

Warsta, M. 2004. Corruption in Thailand. Retrieved September 1 2014 from: aceproject.org/eroen/regions/asia/TH/Corruption_in_Thailand.pdf.

Winijkulchai, A., McQuay, K. 2013. Forensic Science Enhances Access to Justice and Human Rights Protection

in Thailand. Retrieved September 2 2014 from asiafoundation.org/in-asia/2013/02/27/forensicscience-enhances-access-to-justice-and-human-rights-protection-in-thailand.

Wu, W., Vander Beken, T. 2010. Police Torture in China and its Causes: A Review of Literature. The

Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 43 (3): 557-579.

[19]

You might also like

- The Study of Public Participation in Crime Prevention and Suppression at Samrae Police Station, BangkokDocument12 pagesThe Study of Public Participation in Crime Prevention and Suppression at Samrae Police Station, BangkokICGPNo ratings yet

- A Pilot Study of The Acceptance of 1 Malaysia Concept From The Malaysians in Kuala Perlis, Perlis StateDocument8 pagesA Pilot Study of The Acceptance of 1 Malaysia Concept From The Malaysians in Kuala Perlis, Perlis StateICGPNo ratings yet

- Arab Spring and The Rise of Political Islam in EgyptDocument7 pagesArab Spring and The Rise of Political Islam in EgyptICGPNo ratings yet

- The Impact of ASEAN Transition To ASEAN Economic Community On Myanmar EconomyDocument8 pagesThe Impact of ASEAN Transition To ASEAN Economic Community On Myanmar EconomyICGP100% (2)

- A Feasibility Study To Inaugurate The Rangsit Crime SurveyDocument12 pagesA Feasibility Study To Inaugurate The Rangsit Crime SurveyICGPNo ratings yet

- The Relationship between Parents’ Self-Perceived Family Communication Patterns, Self-Reported Conflict Management Styles, and Self-Reported Relationship Satisfaction with Their Children in Thimphu City, BhutanDocument10 pagesThe Relationship between Parents’ Self-Perceived Family Communication Patterns, Self-Reported Conflict Management Styles, and Self-Reported Relationship Satisfaction with Their Children in Thimphu City, BhutanICGPNo ratings yet

- Policy Change and Conflict Resolution in Nigeria: A Case Study of The Niger Delta RegionDocument7 pagesPolicy Change and Conflict Resolution in Nigeria: A Case Study of The Niger Delta RegionICGPNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Smith Bell Dodwell Shipping Agency Corporation vs. BorjaDocument7 pagesSmith Bell Dodwell Shipping Agency Corporation vs. BorjaElephantNo ratings yet

- Adjeibi Kojo II. V Opanin Kwadwo Bonsie and Another (1957) - 1-W.L.R.-1223Document6 pagesAdjeibi Kojo II. V Opanin Kwadwo Bonsie and Another (1957) - 1-W.L.R.-1223Tan KSNo ratings yet

- PP v. Palanas - Case DigestDocument2 pagesPP v. Palanas - Case DigestshezeharadeyahoocomNo ratings yet

- Consti SamplexDocument2 pagesConsti SamplexphoebelazNo ratings yet

- (U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictDocument5 pages(U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictFauquier NowNo ratings yet

- Ownership Theory PDFDocument6 pagesOwnership Theory PDFHärîsh KûmärNo ratings yet

- Philippine legal heirs affidavit formDocument3 pagesPhilippine legal heirs affidavit formArt Bastida63% (8)

- Hennepin County R Kelly ComplaintDocument6 pagesHennepin County R Kelly ComplaintStephen LoiaconiNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 202661Document1 pageG.R. No. 202661alyNo ratings yet

- Fernando Gallardo V. Juan Borromeo: DecisionDocument2 pagesFernando Gallardo V. Juan Borromeo: DecisionKRISTINE MAE A. RIVERANo ratings yet

- Hazel v. United States, 4th Cir. (2008)Document3 pagesHazel v. United States, 4th Cir. (2008)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wills Handout PDFDocument52 pagesWills Handout PDFMichael CarrNo ratings yet

- EriazariDiisi MbararaTradingStoresDocument8 pagesEriazariDiisi MbararaTradingStoresReal TrekstarNo ratings yet

- SIson v. PeopleDocument4 pagesSIson v. PeopleJustin Moreto50% (2)

- Law - Midterm ExamDocument2 pagesLaw - Midterm ExamJulian Mernando vlogsNo ratings yet

- SC Judgment On Anti-Arbitration InjunctionDocument9 pagesSC Judgment On Anti-Arbitration InjunctionLatest Laws TeamNo ratings yet

- Graft and CorruptionDocument9 pagesGraft and CorruptionMel Jazer CAPENo ratings yet

- 19) Marbury Vs Madison Case DigestDocument2 pages19) Marbury Vs Madison Case DigestJovelan V. Escaño100% (1)

- 0 - Arrest Without WarrantDocument43 pages0 - Arrest Without WarrantShadNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 126376 CASE TITLE: Sps Bernardo Buenaventura and Consolacion Joaquin vs. Ca November 20, 2003 FactsDocument1 pageG.R. No. 126376 CASE TITLE: Sps Bernardo Buenaventura and Consolacion Joaquin vs. Ca November 20, 2003 FactsadorableperezNo ratings yet

- Public NuisanceDocument13 pagesPublic Nuisancevaishali guptaNo ratings yet

- JA BaltazarDocument5 pagesJA BaltazarmarlonNo ratings yet

- Solo Parent Form 1Document1 pageSolo Parent Form 1Johven Centeno Ramirez100% (1)

- Belleville Police Dispatch Logs: Sept. 5-12Document7 pagesBelleville Police Dispatch Logs: Sept. 5-12Austen SmithNo ratings yet

- LRTA v. Venus: Issue: W/N LRTA Is Subject To The Provisions of Labor Code Thereby Allowing TheDocument2 pagesLRTA v. Venus: Issue: W/N LRTA Is Subject To The Provisions of Labor Code Thereby Allowing TheMa. Ruth CustodioNo ratings yet

- Designation Order Johnbergin 2018Document8 pagesDesignation Order Johnbergin 2018JOHNBERGIN E. MACARAEGNo ratings yet

- Miguel Katipunan Et Al Vs Braulio Katipunan JRDocument9 pagesMiguel Katipunan Et Al Vs Braulio Katipunan JRCatherine MerillenoNo ratings yet

- Pelaez V Auditor General - LasamDocument2 pagesPelaez V Auditor General - LasamPilyang SweetNo ratings yet

- Democracy: Culture Mandala, Bulletin of The Centre For East-West Cultural and Economic Studies.: "Although Han FeiDocument6 pagesDemocracy: Culture Mandala, Bulletin of The Centre For East-West Cultural and Economic Studies.: "Although Han FeiMark LeiserNo ratings yet

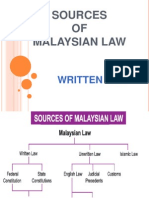

- Written LawDocument54 pagesWritten LawIrsyad Khir100% (1)