Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Robert McCulloch Memo in Support of Motion To Dismiss

Uploaded by

Jason Sickles, Yahoo NewsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Robert McCulloch Memo in Support of Motion To Dismiss

Uploaded by

Jason Sickles, Yahoo NewsCopyright:

Available Formats

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc.

#: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 1 of 17 PageID #: 1055

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MISSOURI

EASTERN DIVISION

GRAND JUROR DOE,

Plaintiff,

v.

ROBERT P. MCCULLOCH, in his

official capacity as Prosecuting Attorney

for St. Louis County, Missouri,

Defendant.

)

)

)

)

) Case 4:15-cv-6-RWS

)

)

)

)

)

)

REPLY MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANT

ROBERT P. MCCULLOCHS MOTION TO DISMISS

INTRODUCTION

Plaintiff was a member of the state grand jury that declined to indict former

Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson in the August 2014 shooting death of

Michael Brown. Plaintiff began his grand jury service on May 7, 2014, when he was

sworn and received his charge from the Honorable Carolyn C. Whittington of the St.

Louis County Circuit Court. See Exhibit A, attached hereto.

Not long after Wilson shot Brown on August 9, 2014, Defendant publicly

declared his intention to submit the matter to a grand jury for consideration, and on

August 20, 2014, Defendant appeared before the grand jury to introduce himself

and his staff, explain the situation, and to take questions. See Transcript of Grand

Jury, Vol. I, at 5:1-24:8, filed by Plaintiff as part of Exhibit C to his complaint; see

also Doc. 1 17 (quoting from Defendants August 20, 2014, remarks to the grand

jury).

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 2 of 17 PageID #: 1056

Plaintiffs grand jury service was formally extended on September 10, 2014,

when he and his fellow grand jurors were recharged by Judge Whittington for the

express purpose of investigating the circumstances of Browns death. See Exhibit B,

attached hereto.

On November 24, 2014, the grand jury returned a no true bill on all the

charges against Officer Wilson, and Plaintiff was discharged from his grand jury

service.

Despite having been duly sworn and twice charged to keep secret the counsel

of the state, his fellows, and his own, Plaintiff now claims it is intolerable that he

should be held to his oath or made to abide by his charge. Plaintiff acknowledges

that the conduct in which he wishes to engage would violate his charge and place

him in contempt of the St. Louis County Circuit Court, and indeed, on

November 17, 2014, Judge Whittington rejected a request by the grand jury to issue

a statement when it completed its work. See Exhibit C, attached hereto.1

However, rather than seeking declaratory or other relief from the St. Louis

County Circuit Court where he received his charge, Plaintiff filed suit against

Defendant in federal court requesting this Courts permission to ignore Judge

Exhibits A, B, and C are offered to establish that Plaintiff lacks standing, and thus, may be

considered by the Court in connection with Defendants motion to dismiss. See, e.g., Taylor v. Lew,

No. 4:13-CV-2481-SNLJ, 2014 WL 4724689, at *3 (E.D. Mo. Sept. 23, 2014) (Motions to dismiss

based on Rule 12(b)(1) may either facially attack plaintiff's allegations or present evidence to

challenge the factual basis on which subject matter jurisdiction rests. (citing Jessie v. Potter, 516

F.3d 709, 71213 (8th Cir. 2008)). However, given that said exhibits are being offered by Defendant

for the first time in his reply brief, Defendant would not object if Plaintiff were to request leave to

file a surresponse in order to counter Defendants exhibits.

1

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 3 of 17 PageID #: 1057

Whittingtons orders and eschew the responsibilities he assumed as a Missouri

grand juror.

As argued below, Plaintiff has no right under the First Amendment to violate

his oath or disregard Missouri law, and the Court should dismiss Plaintiffs claims

for failure to state a claim. However, even if Plaintiffs claims were otherwise

colorable, this Court should not permit Plaintiff to sidestep the court to whom

Plaintiff swore his oath and by which he was twice charged to obey the law.

ARGUMENT

I.

Court lacks subject matter jurisdiction over Plaintiffs claims.

A. Standing.

In order to establish standing for the purposes of Article III of the

Constitution, a plaintiff must show, among other things, that his injuries would be

redressed by a favorable decision. Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 56061 (1992). An injury is redressable if it fairly can be traced to the challenged action

of the defendant, and not injury that results from the independent action of some

third party not before the court. Simon v. E. Ky. Welfare Rights Org., 426 U.S. 26,

41-42 (1976).

In this case, Plaintiff claims to fear prosecution by Defendant under various

statutes, including sections 540.320, 540.310, 540.080, and 540.120. Mo. Rev. Stat.

540.320, 540.310, 540.080, & 540.120. However, of the four statutes cited by

Plaintiff, only section 540.320 carries a criminal penalty enforceable against grand

jurors. Mo. Rev. Stat. 540.320. Accordingly, unless Plaintiff plans to violate

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 4 of 17 PageID #: 1058

section 540.320, he cannot show that an injunction entered against Defendant

would do anything to redress his purported injuries or allay his fears. Simon, 426

U.S. at 41-42; see also Wieland v. U.S. Dept of Health & Hum. Serv., 978 F. Supp.

2d 1008, 1014-15 (E.D. Mo. 2013).

Plaintiff did not allege in his complaint that he wanted to disclose any

evidence or witnesses that have not already been made public. However, in his

opposition to Defendants motion to dismiss, Plaintiff took the remarkable position

that he should be allowed to disclose whatever information he wants, whenever he

wants, regardless of the settled expectations of witnesses and other participants in

the grand jury proceedings, the effect such disclosure may have on future grand

juries, or the danger such disclosure might pose to the witnesses or other persons

whose identities thus far have remained a secret.

Given that Plaintiff has not alleged in his complaint that he intends to

disclose evidence or witnesses that have not already been made public, Defendant is

skeptical that Plaintiff is truly at risk of being prosecuted for making such

disclosures. Cf. Zanders v. Swanson, 573 F.3d 591, 593-94 (8th Cir. 2009) (a plaintiff

must face a credible threat of present or future prosecution under the statute for a

claimed chilling effect to confer standing to challenge the constitutionality of a

statute that both provides for criminal penalties and abridges First Amendment

rights). However, assuming for the sake of argument that Plaintiff wishes to

proceed as recklessly as he suggests, the First Amendment would not shield

Plaintiff from criminal prosecution under section 540.320. Indeed, as argued by

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 5 of 17 PageID #: 1059

Defendant in his initial memorandum and in Part II below, grand jury secrecy is

intended to encourage freedom of disclosure by witnesses and others, and an order

permitting Plaintiff to disregard the restrictions placed on him by section 540.320

would undermine the integrity of Missouris grand jury system and place witnesses

and others in jeopardy.

Although Plaintiff requests the Court to enjoin Defendant from prosecuting

Plaintiff under section 540.320, most of the information Plaintiff wishes to divulge

is protected from disclosure by sections 540.080 (Oath of grand jurors) and

540.310 (Cannot be compelled to disclose vote). Mo. Rev. Stat. 540.320, 540.310,

& 540.080. However, given that neither section 540.080 nor section 540.310 carries

a criminal penalty provision, Plaintiff cannot show an injunction entered against

Defendant would redress Plaintiffs purported injuries. Simon, 426 U.S. at 41-42;

Mo. Rev. Stat. 540.080 & 540.310.

In his opposition to Defendants motion to dismiss, Plaintiff concedes that

sections 540.080 and 540.310 do not carry criminal penalties. Nevertheless, Plaintiff

argues that [r]ules governing grand jury proceedings have long been enforced

through criminal contempt actions, and that [Defendant], as the prosecuting

attorney for St. Louis County, is responsible for commencing and prosecuting any

contempt proceeding. Doc. 33 at 5-6.

Although Defendant has broad authority as the elected prosecutor for St.

Louis County to initiate criminal proceedings on behalf of the County or the State,

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 6 of 17 PageID #: 1060

see Mo. Rev. Stat. 56.060, Plaintiff has cited no authority to support his

contention that Defendant could unilaterally prosecute Plaintiff for contempt.

Criminal contempt is a power given to the courts, not prosecutors, and is

not, strictly speaking, a criminal proceeding. Ramsey v. Grayland, 567 S.W.2d 682,

686 (Mo. App. 1978); State ex rel. Chassaing v. Mummert, 887 S.W.2d 573, 579 (Mo.

banc 1994) (same); see also Smith v. Pace, 313 S.W.3d 124, 129-30 (Mo. banc 2010)

(Missouri courts have both an inherent power under the constitution to punish for

contempt as well as authority to try contempt-of-court cases under the statutory

crime of contempt); Osborne v. Purdome, 244 S.W.2d 1005, 1012 (Mo. banc 1951)

(courts have inherent power to hold persons in contempt); Mo. Rev. Stat. 476.110

(granting [e]very court of record the power to punish criminal contempt). Indeed,

and as the cases relied on by Plaintiff demonstrate, persons challenging a judgment

must seek a writ against the issuing judge rather than against the prosecutor.

Smith, 313 S.W.3d at 136 (reversing finding of contempt against attorney by

complainant judge); Ramsey, 567 S.W.2d at 691 (sufficient evidence to support

trial judges finding of contempt); Ex parte Creasy, 148 S.W. 914, 921 (Mo. banc

1912) (reversing trial judges finding of contempt against grand jury witness); Ex

parte Shull, 121 S.W. 10, 12 (Mo. 1909) (reversing trial judges finding of contempt

against witness alleged to have been disrespectful).

In this case, Plaintiff makes much of the fact that Defendant handed the

grand jurors copies of Missouris secrecy laws before they were discharged, and

thus, argues Defendants action shows he embraced rather than rejected the

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 7 of 17 PageID #: 1061

statutes. Doc. 33 at 4; Doc. 1 28. However, whether Defendant has embraced or

rejected the laws governing grand jury secrecy is not relevant to whether an

injunction against Defendant would redress Plaintiffs purported injuries. Indeed,

Judge Whittington has a clear prerogative to enforce her own orders regardless of

Defendants participation or consent, and Defendant has no independent authority

under the law to prosecute Plaintiff for contempt absent the approval and active

participation of the court. Accordingly, Plaintiff cannot establish that his purported

injuries can fairly be traced to Defendant or that an injunction against Defendant

would redress said injuries. Simon, 426 U.S. at 41-42.

B. Eleventh Amendment immunity.

Defendant is entitled to Eleventh Amendment immunity on Plaintiffs claims

in this case because, as argued above, Defendant has no independent authority to

prosecute Plaintiff for contempt absent the approval and active participation of the

St. Louis County Circuit Court where Plaintiff was charged. See, e.g., Ex Parte

Young, 209 U.S. 123, 157 (1908) (defendant official must have some connection

with the enforcement of the act to be enjoined); see also 281 Care Comm. v.

Arneson, 766 F.3d 774, 797 (8th Cir. 2014).

In his opposition to Defendants motion to dismiss, Plaintiff argues that

Defendant is not entitled to immunity under the Eleventh Amendment because he

is neither a state nor a state official. Doc. 33 at 11. However, Plaintiffs arguments

lack merit.

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 8 of 17 PageID #: 1062

In deciding whether a particular instrumentality of the state may invoke

immunity under the Eleventh Amendment, the court must inquire[] into the

relationship between the State and the entity in question. Regents of the Univ. of

Calif. v. Doe, 519 U.S. 425, 429 (1997). In making this inquiry, the courts may

examine the essential nature of the proceeding at issue or the nature of the entity

created by state law. Id. at 429-30.

In this case, Plaintiff is requesting the Court to enjoin Defendant from acting

in his official capacity as the elected prosecutor for St. Louis County to prosecute

Plaintiff under Missouri law. Doc. 1 8. Defendant has broad powers to prosecute

persons in St. Louis County under state law, see Mo. Rev. Stat. 56.060, and the

prosecution Plaintiff seeks to enjoin would implicate Defendants powers and duties

as a quasi-judicial officer representing the people of Missouri. State ex rel Jackson

County Prosecuting Attorney v. Prokes, 363 S.W.3d 71, 85 (Mo. App. W.D. 2011) (a

prosecuting attorney in a criminal case acts as a quasi-judicial officer representing

the people of the State.); see also State v. Todd, 433 S.W.2d 550, 554 (Mo. 1968)

(authority of county prosecutors in Missouri is carved out of Missouri Attorney

Generals overriding authority as states chief legal officer). Accordingly, Defendant

may invoke immunity under the Eleventh Amendment. Regents of the Univ. of

Calif., 519 U.S. at 429; see also McMillan v. Monroe County, 520 U.S. 781, 786-87

(1997); Bibbs v. Newman, 997 F. Supp. 1174, 1177-81 (S.D. Ind. 1998) (state

prosecutor was state official for Eleventh Amendment purposes).

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 9 of 17 PageID #: 1063

C. Plaintiffs claims are not ripe.

To the extent Plaintiff has standing to assert claims against Defendant under

section 540.320, such claims are not ripe. Mo. Rev. Stat. 540.320. Indeed, given

that it is unclear from Plaintiffs complaint whether he truly intends to divulge

witnesses and evidence that has been redacted or otherwise withheld by Defendant,

it would be premature for the Court to enjoin a prosecution that may never occur.

See, e.g., Missouri Roundtable for Life v. Carnahan, 676 F.3d 665, 674 (8th Cir.

2012) (ripeness depends on whether the case involves contingent future events that

may not occur as anticipated, or indeed may not occur at all). However, assuming

for the sake of argument that Plaintiff plans to disclose witnesses and evidence that

have not been made public, the Court should nevertheless abstain from deciding

Plaintiffs claims, as the applicability of the Missouri Sunshine Law to such

information presents an uncertain issue of state law that should be settled by a

Missouri court. See Harman v. Forssenius, 380 U.S. 528, 534 (1965) (citing R.R.

Commn v. Pullman Co., 312 U.S. 496 (1941)).

II.

Plaintiff has not stated a claim upon which relief may be granted.

In his opposition to Defendants motion to dismiss, Plaintiff argues that

Missouri has no remaining interest in maintaining secrecy to weigh against

[Plaintiffs] First Amendment rights in this case, and he complains that the

information released by Defendant thus far provides only an appearance of

transparency but does not fully portray the proceedings before the grand jury.

Doc. 33 at 6, 16; see also Doc. 1 33, 58. Plaintiff further complains that

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 10 of 17 PageID #: 1064

Defendants public statements have mischaracterized Plaintiffs views, and he seeks

an injunction giving him full freedom to discuss his experience and opinions as a

grand juror, including his impression that the presentation of evidence was handled

differently by the state in the Wilson investigation than in the hundreds of other

matters considered by Plaintiffs grand jury. Doc. 1 19-20.

Plaintiffs arguments lack merit, and the Court should dismiss Plaintiffs

complaint for failure to state a claim. The Supreme Court has consistently

recognized that the proper functioning of the grand jury system depends upon the

secrecy of grand jury proceedings. Douglas Oil Co. of California v. Petrol Stops

Northwest, 441 U.S. 211, 218-19 (1979) (citing U.S. v. Proctor & Gamble Co., 356

U.S. 677 (1958)). The grand jury system is deeply rooted in the federal and state

courts in the United States, see Brandzburg v. Hayes, 408 U.S. 665, 686-87 (1972),

and [i]n the absence of a clear indication in a statute or Rule, [a court] must always

be reluctant to conclude that a breach of [grand jury] secrecy has been authorized.

U.S. v. Sells Eng'g, Inc., 463 U.S. 418, 425 (1983) (citing Illinois v. Abbott & Assoc.,

Inc., 460 U.S. 557, 572 (1983)); see also Mannon v. Frick, 295 S.W.2d 158, 162 (Mo.

1956); State ex rel Clagett v. James, 327 S.W.2d 278, 284 (Mo. banc 1959);

Palmentere v. Campbell, 205 F. Supp. 261, 264 (W.D. Mo. 1962). Although the

governments interest in secrecy is said to diminish once a grand jury has completed

its work, in considering the effects of disclosure on grand jury proceedings, the

courts must consider not only the immediate effects upon a particular grand jury,

10

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 11 of 17 PageID #: 1065

but also the possible effect upon the functioning of future grand juries. Douglas Oil,

441 U.S. at 222.

Plaintiffs term as a grand juror began in May 2014, and ended in

November 2014. During that time, Plaintiff and his fellow grand jurors considered

hundreds of cases presented by Defendants office. Although Defendant has publicly

released redacted copies of all the testimony and nearly all the evidence presented

to the grand jury in connection with the Wilson investigation, see Exhibit C to

Plaintiffs complaint, he has not released any information from any of the hundreds

of other cases considered by Plaintiffs grand jury.

Plaintiff has provided no support for his contention that he should be

permitted to disclose information relating to any of the hundreds of cases the grand

jury considered prior to the Wilson investigation. Nor has Plaintiff provided a valid

basis for disclosing witnesses or evidence that Defendant has withheld from the

Wilson investigation. Defendant withheld the names of witnesses and others in

order to protect them from harm. See Doc. 1-4; see also Mo. Rev. Stat. 610.100.3.

However, such redactions are also justified by the need to protect the settled

expectations of witnesses and others that appeared before Plaintiffs grand jury, and

to encourage the participation of witnesses in future grand juries. Douglas Oil, 441

U.S. at 222; see also Rehberg v. Paulk, 132 S.Ct. 1497, 1509 (2012) (disclosure of

preindictment grand jury proceedings would chill participation by witnesses);

Brandzburg, 408 U.S. at 700 (characteristic secrecy of grand jury proceedings

protects interests of those compelled to participate in grand jury process); CBS Inc.

11

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 12 of 17 PageID #: 1066

v. Campbell, 645 S.W.2d 30, 33 (Mo. App. E.D. 1983) (The secrecy of the grand jury

proceeding . . . ameliorates the harmful effects of disclosure that would result in an

ordinary civil or criminal trial.).2

Plaintiff complains that Defendant has mischaracterized Plaintiffs view of

the evidence, but such claims are baseless. Defendant does not know Plaintiffs

identity or how he voted, and Defendant has never purported to speak for any grand

juror individually. Although Plaintiff may now regret having sworn his oath and

accepted his charge, Plaintiff has no right to publicly report his impressions, and it

has long been established that a prosecutor, unlike a grand juror, is competent to

discuss the evidence presented to a grand jury. See, e.g., State v. Grady, 84 Mo. 220,

224 (1884); see also In the Matter of Interim Report of the Grand Jury, 553 S.W.2d

479, 482 (Mo. banc 1977); In the Matter of the Report of the Grand Jury, 612

S.W.2d 864, 865-66 (Mo. App. E.D. 1981); In the Matter of Regular Report of Grand

Jury, 585 S.W.2d 76, 77 (Mo. App. E.D. 1979).

Moreover, and notwithstanding Plaintiffs cavils that the information

released by Defendant has not fully portrayed the grand jury proceedings,

Plaintiff has provided no support for his suggestion that the release of some grand

jury information necessarily requires the release of everything. Indeed, complete

transparency is anathema to the very nature of a grand jury, which depends upon

On March 4, 2015, the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) issued an 86-page report

summarizing the evidence against Wilson. The DOJ report, a copy of which is available online at

http://www.justice.gov/usao/pam/Documents/DOJ%20Report%20on%20Shooting%20of%20Michael%

20Brown.pdf, found that Wilsons use of deadly force was not objectively unreasonable, and

concluded it was not appropriate to present the matter to a federal grand jury for indictment. Id. at

5. With the exception of Darren Wilson and Michael Brown, the DOJ redacted the names of all

individuals to safeguard against an invasion of their personal privacy. Id. at 6 n.2

2

12

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 13 of 17 PageID #: 1067

secrecy and anonymity for its proper functioning. See Douglas Oil, 441 U.S. at 222;

Rehberg, 132 S.Ct. at 1509; Sells Eng'g, Inc., 463 U.S. at 425; Mannon, 295 S.W.2d

at 162; Palmentere, 205 F. Supp. at 264; see also Seattle Times Co. v. Rhinehart,

467 U.S. 20, 35 (1984) (state court protective orders permit civil litigants to receive

information that not only is irrelevant but if publicly disclosed could be damaging

to reputation and privacy).

Nor does Plaintiff offer any support for his position that he should be allowed

to disclose the counsel of the state, his fellows, or his own, the identities of his fellow

grand jurors, or the content and nature of the grand jurys votes and deliberations.

Mo. Rev. Stat. 540.080 & 540.310. Such information is absolutely prohibited from

disclosure in Missouri, Mannon, 295 S.W.2d at 162, and the Butterworth decision

relied on by Plaintiff provides no authority to suggest that a grand juror has a right

to share his experiences or opinions as such. Butterworth v. Smith, 494 U.S. 624,

629 n.2, 631-32 (1990) (witness may divulge information of which he was in

possession before he testified before the grand jury, and not information which he

may have obtained as a result of his participation in the proceedings of the grand

jury); see also Rhinehart, 467 U.S. at 32 (A litigant has no First Amendment right

of access to information made available only for the purposes of trying his suit.

(citing Zemel v. Rusk, 381 U.S. 1, 16-17 (1965)). Indeed, it is well established that a

private citizen lacks a judicially cognizable interest in the prosecution or

nonprosecution of another, Linda R.S. v. Richard D., 410 U.S. 614, 619 (1973), and

although the law disfavors the ad hoc creation of new categories of prohibited

13

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 14 of 17 PageID #: 1068

speech, the Supreme Court has recognized that speech may be proscribed in order to

protect the integrity of important governmental processes. See U.S. v. Alvarez, 132

S.Ct. 2537, 2546 (2012).

Given the long line of federal and Missouri cases recognizing the central

importance of secrecy to the proper functioning of grand juries, there is no question

that Missouris interest in secrecy outweighs whatever personal interest Plaintiff

may have in sharing his experience and opinions. See, e.g., Douglas Oil, 441 U.S. at

222; Rehberg, 132 S.Ct. at 1509; Sells Eng'g, Inc., 463 U.S. at 425; Mannon, 295

S.W.2d at 162; State ex rel Clagett, 327 S.W.2d at 284; Palmentere, 205 F. Supp. at

264; see also Butterworth, 494 U.S. at 636-37 (loosening grand jury secrecy risks

subject[ing] grand jurors to a degree of press attention and public prominence that

might in the long run deter citizens from fearless performance of their grand jury

service (Scalia, J., concurring)). Accordingly, the Court should dismiss Plaintiffs

complaint for failure to state a claim.

III.

The Court should abstain from exercising jurisdiction.

The issues raised by Plaintiff in this case involve important questions of state

law in which Missouri has a strong interest. Accordingly, in the event this Court

finds that Plaintiffs claims are otherwise colorable and ripe for adjudication, it

should abstain from exercising its jurisdiction. Beavers v. Arkansas State Bd. of

Dental Examiners, 151 F.3d 838, 840 (8th Cir. 1990) (abstention is appropriate in

order to preserve traditional principles of equity, comity, and federalism

(quotations omitted)). Indeed, abstention is particularly appropriate in this case,

14

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 15 of 17 PageID #: 1069

where Plaintiff seeks to engage in conduct that would place him in direct violation

of Missouri law and in contempt of a state courts orders. See Chem. Fireproofing

Corp. v. Bronksa, 553 S.W.2d 710, 718 (Mo. App. 1977) (Contempt proceedings are

sui generis and are triable only by the court against whose authority the contempts

are charged. (punctuation and citations removed)); see also Douglas Oil, 441 U.S.

at 226 (in general, requests for disclosure of grand jury transcripts should be

directed to the court that supervised the grand jurys activities).

Although Plaintiff suggests that Missouris courts will not afford him a

sufficient opportunity to assert his claimed rights under the First Amendment, the

Eighth Circuit has cautioned federal courts against engag[ing] any presumption

that the state courts will not safeguard federal constitutional rights. Norwood v.

Dickey, 409 F.3d 901, 904 (8th Cir. 2005) (quoting Neal v. Wilson, 112 F.3d 351, 357

(8th Cir.1997)). Accordingly, should the Court find that it has jurisdiction and that

Plaintiffs claims are otherwise colorable, the Court should abstain from exercising

its jurisdiction in the interest of equity, comity, and federalism.

CONCLUSION

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, Defendant McCulloch respectfully

requests the Court grant his Motion to Dismiss, and any other relief the Court

deems fair and appropriate.

15

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 16 of 17 PageID #: 1070

Respectfully submitted,

CHRIS KOSTER,

Attorney General

/s/ David Hansen

DAVID HANSEN

Assistant Attorney General

Missouri Bar No. 40990

Post Office Box 899

Jefferson City, MO 65102

Phone: (573) 751-9635

Fax: (573) 751-2096

David.Hansen@ago.mo.gov

PETER J. KRANE

St. Louis County Counselors Office

Missouri Bar No. 32546

41 South Central Avenue

Clayton, MO 63015

Phone: (314) 615-7042

PKrane@stlouisco.com

H. ANTHONY RELYS

Assistant Attorney General

Missouri Bar No. 63190

Assistant Attorney General

Post Office Box 861

St. Louis, MO 63188

Phone: (314) 340-7861

Fax: (314) 340-7029

Tony.Relys@ago.mo.gov

ATTORNEYS FOR DEFENDANT

ROBERT P. MCCULLOCH

16

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 38 Filed: 03/27/15 Page: 17 of 17 PageID #: 1071

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on March 27, 2015, the foregoing Reply Memorandum in

Support of Defendant Robert P. McCullochs Motion to Dismiss was filed and served

via the Courts electronic filing system upon all counsel of record.

/s/ David Hansen

David Hansen

Assistant Attorney General

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Carlson ComplaintDocument8 pagesCarlson ComplaintMediaite100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Unredacted Transcript of Call Between Omar Mateen and Orlando 911Document1 pageUnredacted Transcript of Call Between Omar Mateen and Orlando 911Jason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Omar Mateen Criminal ChargeDocument1 pageOmar Mateen Criminal ChargeJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Orlando Nightclub Shooting TranscriptDocument3 pagesOrlando Nightclub Shooting TranscriptJason Sickles, Yahoo News100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Omar Mateen Letter of RecommendationDocument1 pageOmar Mateen Letter of RecommendationJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Read Remarks of FBI Director James ComeyDocument7 pagesRead Remarks of FBI Director James Comeykballuck1100% (2)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Orlando Shooter Omar Mateen's AutopsyDocument17 pagesOrlando Shooter Omar Mateen's AutopsyJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Omar Mateen Florida Security Guard RecordsDocument63 pagesOmar Mateen Florida Security Guard RecordsJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

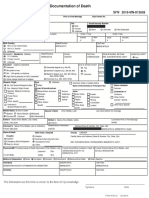

- Prince Documentation of DeathDocument1 pagePrince Documentation of DeathJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Prince Invoice From City of Moline, Illinois For Emergency ResponseDocument1 pagePrince Invoice From City of Moline, Illinois For Emergency ResponseJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Prince Autopsy ReportDocument1 pagePrince Autopsy ReportJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Order Appointing Special Administrator in Prince Rogers Nelson EstateDocument2 pagesOrder Appointing Special Administrator in Prince Rogers Nelson EstateMinnesota Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Prince Search Warrant SealedDocument5 pagesPrince Search Warrant SealedJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Meechaiel Criner Arrest Warrant in UT Student HomicideDocument5 pagesMeechaiel Criner Arrest Warrant in UT Student HomicideJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Suspected Kalamazoo Shooter Jason Dalton Criminal ComplaintDocument3 pagesSuspected Kalamazoo Shooter Jason Dalton Criminal ComplaintJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Moline, Illinois Fire Department Records On Prince Emergency LandingDocument8 pagesMoline, Illinois Fire Department Records On Prince Emergency LandingJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- TSA Terms and Conditions For Trained CaninesDocument30 pagesTSA Terms and Conditions For Trained CaninesJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Jason Dalton Police Search Warrant ReturnsDocument4 pagesJason Dalton Police Search Warrant ReturnsJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Dylann Roof Arrest Police Incident ReportDocument4 pagesDylann Roof Arrest Police Incident ReportJason Sickles, Yahoo News100% (1)

- Understanding Firearms Assaults Against Police in The USDocument60 pagesUnderstanding Firearms Assaults Against Police in The USJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Jason Dalton's Interview With Kalamazoo PoliceDocument10 pagesJason Dalton's Interview With Kalamazoo PoliceJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Jared Fogle Guilty Plea AgreementDocument27 pagesJared Fogle Guilty Plea AgreementJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Ferguson Chief of Police Final Four CandidatesDocument2 pagesFerguson Chief of Police Final Four CandidatesJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Waco, Texas Twin Peaks Arrest ReportDocument1 pageWaco, Texas Twin Peaks Arrest ReportJason Sickles, Yahoo News100% (1)

- Michael Brown Family Wrongful Death SuitDocument44 pagesMichael Brown Family Wrongful Death SuitJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Waco Police Response To Yahoo NewsDocument4 pagesWaco Police Response To Yahoo NewsJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Judge's Evidence Ruling in Eric Casebolt Arrest of Albert BrownDocument4 pagesJudge's Evidence Ruling in Eric Casebolt Arrest of Albert BrownJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- James Holmes NotebookDocument35 pagesJames Holmes NotebookJason Sickles, Yahoo News75% (4)

- State of Colorado v. James Holmes Jury QuestionnareDocument18 pagesState of Colorado v. James Holmes Jury QuestionnareJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 The President's Domestic PowersDocument27 pagesLesson 3 The President's Domestic PowersEsther EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Comment Opposition Waiver To File FOEDocument5 pagesComment Opposition Waiver To File FOERab AlvaeraNo ratings yet

- Jacob Ajomale v. Eric Holder, JR., 4th Cir. (2011)Document4 pagesJacob Ajomale v. Eric Holder, JR., 4th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Provisional Remedies Midterm PDFDocument46 pagesProvisional Remedies Midterm PDFPhil JaramilloNo ratings yet

- Evidence 2 (Object Vs Documentary Evidence)Document6 pagesEvidence 2 (Object Vs Documentary Evidence)westernwound82No ratings yet

- United States v. Vincent Gugliaro, 501 F.2d 68, 2d Cir. (1974)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Vincent Gugliaro, 501 F.2d 68, 2d Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Deangelo Whiteside v. United States, 4th Cir. (2014)Document69 pagesDeangelo Whiteside v. United States, 4th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument10 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- RTI - Authorization LetterDocument1 pageRTI - Authorization LetterSurendera M. BhanotNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Legal Successors of Deceased Employee Insured Under ESI Act, 1948 Not Entitled For Compensation Under Workmen Compensation Act, 1923Document8 pagesLegal Successors of Deceased Employee Insured Under ESI Act, 1948 Not Entitled For Compensation Under Workmen Compensation Act, 1923Live LawNo ratings yet

- Administrative Tribunal ProjectDocument17 pagesAdministrative Tribunal ProjectAnsh Patel100% (1)

- 210 Interpretation of StatutesDocument119 pages210 Interpretation of Statutesbhatt.net.in100% (3)

- Boracay Foundation, Inc. v. Province of AklanDocument3 pagesBoracay Foundation, Inc. v. Province of Aklankjhenyo21850263% (8)

- Villa Rey v. CaDocument6 pagesVilla Rey v. CabrendamanganaanNo ratings yet

- Common Carrier of Goods Fulltext Part 1Document98 pagesCommon Carrier of Goods Fulltext Part 1Jo-Al GealonNo ratings yet

- Petitioners vs. VS.: en BancDocument6 pagesPetitioners vs. VS.: en BancJian CerreroNo ratings yet

- Proposed OrderDocument9 pagesProposed OrderABC Action NewsNo ratings yet

- GR No. 172852 (2013) - City of Cebu v. Dedamo, JRDocument3 pagesGR No. 172852 (2013) - City of Cebu v. Dedamo, JRNikki Estores GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Cleaves v. American Management Services Central, L. L. C. Et Al - Document No. 13Document2 pagesCleaves v. American Management Services Central, L. L. C. Et Al - Document No. 13Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Florida Second District Court of Appeals Respondent's Response To MandamusDocument13 pagesFlorida Second District Court of Appeals Respondent's Response To MandamusLarry BradshawNo ratings yet

- AM 11-9-4-SC Efficient Paper RuleDocument2 pagesAM 11-9-4-SC Efficient Paper Ruleglaisa23No ratings yet

- Incentive AwardsDocument18 pagesIncentive AwardsRich LardnerNo ratings yet

- Carl Anthony Gray v. David K. Mapp, Sheriff of the Norfolk City Jail Dr. Clardy, Physician, Norfolk City Jail Y.F. David, Rn, Medical Administrator, Norfolk City Jail M.C. Reynolds, Nurse, Norfolk City Jail Board of Corrections of the State of Virginia Virginia State Board of Housing Edward Murray, Director Ray Kessler, Health Administrator Balvir Kapil, Chief Physician John Doe, Chief Nurse Michael Pfeiffer, Vice President James E. Johnson, Regional Corrections Inspector, Carl Anthony Gray v. Edward G. Murray P.A. Terrangi, Warden H.D. Underwood, Rn Michael Pfeiffer, Vice President, Cms Roscoe Ramsey J. Webster Doctor Ong Doctor Mason K. Hamlin, R.N. Pierre D. Lord, Carl Anthony Gray v. Thomas Lanyi, Dr., Urologist Dr. Welch, Medical Administrator, Department of Corrections Dr. Barnes, Chief Physician, Department of Corrections D.L. Brendlinger, Dr., Radiologist, Department of Corrections L.T. Lester, Warden, Department of Corrections Edward Murray, Director, Department of CorrectionsDocument2 pagesCarl Anthony Gray v. David K. Mapp, Sheriff of the Norfolk City Jail Dr. Clardy, Physician, Norfolk City Jail Y.F. David, Rn, Medical Administrator, Norfolk City Jail M.C. Reynolds, Nurse, Norfolk City Jail Board of Corrections of the State of Virginia Virginia State Board of Housing Edward Murray, Director Ray Kessler, Health Administrator Balvir Kapil, Chief Physician John Doe, Chief Nurse Michael Pfeiffer, Vice President James E. Johnson, Regional Corrections Inspector, Carl Anthony Gray v. Edward G. Murray P.A. Terrangi, Warden H.D. Underwood, Rn Michael Pfeiffer, Vice President, Cms Roscoe Ramsey J. Webster Doctor Ong Doctor Mason K. Hamlin, R.N. Pierre D. Lord, Carl Anthony Gray v. Thomas Lanyi, Dr., Urologist Dr. Welch, Medical Administrator, Department of Corrections Dr. Barnes, Chief Physician, Department of Corrections D.L. Brendlinger, Dr., Radiologist, Department of Corrections L.T. Lester, Warden, Department of Corrections Edward Murray, Director, Department of CorrectionsScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Rem Law Review (Gesmundo) 2nd Sem 2010-2011Document62 pagesCivil Procedure Rem Law Review (Gesmundo) 2nd Sem 2010-2011julia_britanicoNo ratings yet

- Ivoclar Vivadent v. 3M CompanyDocument6 pagesIvoclar Vivadent v. 3M CompanyPriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Keith Caroselli Lee Caroselli Frank Caroselli v. First Interstate Bank of Denver, 15 F.3d 1083, 1st Cir. (1993)Document4 pagesKeith Caroselli Lee Caroselli Frank Caroselli v. First Interstate Bank of Denver, 15 F.3d 1083, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument3 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 2018 10 8 33660 Judgement 23-Feb-2022Document8 pages2018 10 8 33660 Judgement 23-Feb-2022Rutej PimpalkhuteNo ratings yet

- Office of The Court Administrator vs. Hon. Lagura-YapDocument1 pageOffice of The Court Administrator vs. Hon. Lagura-YapAlljun SerenadoNo ratings yet

- Boim V AMPDocument51 pagesBoim V AMPSamantha MandelesNo ratings yet

- Courage to Stand: Mastering Trial Strategies and Techniques in the CourtroomFrom EverandCourage to Stand: Mastering Trial Strategies and Techniques in the CourtroomNo ratings yet

- Evil Angels: The Case of Lindy ChamberlainFrom EverandEvil Angels: The Case of Lindy ChamberlainRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- Greed on Trial: Doctors and Patients Unite to Fight Big InsuranceFrom EverandGreed on Trial: Doctors and Patients Unite to Fight Big InsuranceNo ratings yet

- Litigation Story: How to Survive and Thrive Through the Litigation ProcessFrom EverandLitigation Story: How to Survive and Thrive Through the Litigation ProcessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Art of Fact Investigation: Creative Thinking in the Age of Information OverloadFrom EverandThe Art of Fact Investigation: Creative Thinking in the Age of Information OverloadRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Busted!: Drug War Survival Skills and True Dope DFrom EverandBusted!: Drug War Survival Skills and True Dope DRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- 2017 Commercial & Industrial Common Interest Development ActFrom Everand2017 Commercial & Industrial Common Interest Development ActNo ratings yet