Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ravel's Boléro: Themes and Structure

Uploaded by

Fred FredericksOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ravel's Boléro: Themes and Structure

Uploaded by

Fred FredericksCopyright:

Available Formats

Bolro

Just before departing on his American Tour in 1928, Ravel received a commission from

Ida Rubinstein for a ballet, to be called Fandango. His intention was to orchestrate some

pieces from Iberia by Albniz, but as he was beginning work on it in July, he discovered

that the rights to the music were already assigned to the Spanish composer Enrique

Arbs. Ravel was initially dismayed and at a loss how to fulfil his commission. However

while continuing his holiday in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, he developed a Spanish-sounding

theme which had about it "quelque chose d'insistant".

"L'homme de la rue se

donne la satisfaction de

siffler les premires

mesures du Bolro, mais

bien peu de musiciens

professionnels sont

capables de reproduire

de mmoire, sans une

faute de solfge, la

phrase entire qui obit

de sournoises et

savantes coquetteries."

( mile Vuillermoz,

[1938], p.88-89).

Bolro, as the work was renamed, lasts approximately

15 minutes, and repeats each of the theme's two parts

9 times in the same key, using different orchestrations

to vary the texture and to create a gradual crescendo.

(The pattern is AA BB repeated 4 times, and then a

single repeat of AB, leading to the modulation which

gives the piece its cataclysmic ending.)

Ravel was insistent that the work should be played at

a steady and unvarying tempo (as his own recording

demonstrates). "C'est une danse d'un mouvement trs

modr et constamment uniforme, tant par la mlodie

que par l'harmonie et le rythme, ce dernier marqu

sans cesse par le tambour. Le seul lment de

diversit y est apport par le crescendo orchestral."

(Ravel, [1938]). After a performance in 1930, he

reprimanded Toscanini for taking the work too fast and

for speeding up at the climax. (Coppola, [1944],

p.105)

At the first performance of her ballet production,

at the Opra in November 1928, Ida Rubinstein

danced the role of a flamenco dancer who is

trying out steps on a table in a bar, surrounded

by men whose admiration turns to lustful

obsession. Ravel did not entirely approve; his

own conception was an outdoor scene in front of

a factory whose machinery provides the

In concert performances,

Bolro became Ravel's most

popular work, and it is reputed

to be the world's most

frequently played piece of

classical music. The royalties

earned by the work up to 2001

inflexible rhythm; the factory workers would

emerge to dance together, while a story of a

bullfighter killed by a jealous rival was played

out. ( Chalupt, [1956], p.237). It was performed

in this way, with designs by Lon Leyritz, at the

Opra on one occasion after Ravel's death.

have been estimated at 40

million: an article outlining the

strange history of this money

appeared in The Guardian on

25 April 2001.

Much has been written about Bolro. One detailed analysis of its structure appears in

Deborah Mawer's chapter, "Ballet and the apotheosis of the dance", in The Cambridge

Companion to Ravel, [2000], pp. 155-161. The impact of its repetitive technique (e.g.

4037 drum beats) is considered by Serge Gut in "Le phnomne rptitif chez Maurice

Ravel: de l'obsession l'annihilation incantatoire", in International Review of the

Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, vol.21(1) [June 1990], pp.29-46. [For those with

access to JSTOR, an online version of this article is available.]

Claude Lvi-Strauss considers the semiotics of the work in "Bolro de Maurice Ravel", in

L'Homme, vol.11(2), [1971], pp. 5-14.

And from a performer's perspective, Jean Douay has written about the role of the

trombone - and how to play it - in "Thoughts to Ponder: What Would Ravel Think?--More

Thoughts on Ravel's 'Bolero'", in ITA Journal, vol.26(2), [Spring 1998], p. 23.

www.maurice-ravel.net

You might also like

- J S Bach 413 Chorales AnalyzedDocument2 pagesJ S Bach 413 Chorales Analyzeddesmond ngNo ratings yet

- Defining American Music-NICHOLLSDocument12 pagesDefining American Music-NICHOLLSChristophe BairrasNo ratings yet

- Genre Analysis PaperDocument4 pagesGenre Analysis PaperHPrinceed90No ratings yet

- Missa Solemnis (Beethoven)Document3 pagesMissa Solemnis (Beethoven)j.miguel593515No ratings yet

- C.P.E. Bach's Instruction of Blind Flautist Friedrich Dülon in Late 18th-Century GermanyDocument16 pagesC.P.E. Bach's Instruction of Blind Flautist Friedrich Dülon in Late 18th-Century Germanyeducateencasa alicanteNo ratings yet

- Study of Madrigal CyclesDocument429 pagesStudy of Madrigal CyclesI.M.C.100% (1)

- Ian Shanahan - Full CV 2017Document28 pagesIan Shanahan - Full CV 2017Ian ShanahanNo ratings yet

- Ligeti Etude 18: Canon Slurs Version: Prima Volta: Vivace Poco Rubato Seconda Volta: PrestissimoDocument3 pagesLigeti Etude 18: Canon Slurs Version: Prima Volta: Vivace Poco Rubato Seconda Volta: PrestissimoImri Talgam100% (1)

- Onute Narbutaite: Just Strings and A Light Wind Above Them (2018)Document51 pagesOnute Narbutaite: Just Strings and A Light Wind Above Them (2018)AzuralianNo ratings yet

- Ics Featured Article - 12 Hommages À Paul SacherDocument13 pagesIcs Featured Article - 12 Hommages À Paul SacherEurico Ferreira MathiasNo ratings yet

- Historical Etudes For OboeDocument11 pagesHistorical Etudes For OboeLaerte TavaresNo ratings yet

- RAVEL, MauriceDocument15 pagesRAVEL, MauriceDiego Segade BlancoNo ratings yet

- GrechaninovDocument5 pagesGrechaninovTiziano de FeliceNo ratings yet

- The Devil, The Violin, and Paganini - The Myth of The Violin As Satan's InstrumentDocument24 pagesThe Devil, The Violin, and Paganini - The Myth of The Violin As Satan's InstrumentGabbyNo ratings yet

- Viola SoloDocument3 pagesViola SoloOsnat YoussinNo ratings yet

- 622864Document14 pages622864Kike Alonso CordovillaNo ratings yet

- 4822797-Rujero y Paradetas From The Spanish Suite For Viola GuitarDocument19 pages4822797-Rujero y Paradetas From The Spanish Suite For Viola GuitarFhomensNo ratings yet

- Moondog Essay CompleteDocument9 pagesMoondog Essay CompleteChloe KielyNo ratings yet

- Progressive Growth: Interview with Composer Henri DutilleuxDocument5 pagesProgressive Growth: Interview with Composer Henri DutilleuxewwillatgmaildotcomNo ratings yet

- Guillaume DufayDocument20 pagesGuillaume DufayTam TamNo ratings yet

- Mozart's Oboe Concerto in C Stage 2Document4 pagesMozart's Oboe Concerto in C Stage 2renz_adameNo ratings yet

- Adagio in E Major K. 261 - Solo Part PDFDocument2 pagesAdagio in E Major K. 261 - Solo Part PDFDaniel TianNo ratings yet

- Wren - The Compositional Eclecticism of Bohuslav Martinů. Chamber Works Featuring Oboe, Part II PDFDocument19 pagesWren - The Compositional Eclecticism of Bohuslav Martinů. Chamber Works Featuring Oboe, Part II PDFMelisa CanteroNo ratings yet

- Simeone Note On Janacek DiaryDocument31 pagesSimeone Note On Janacek DiaryNigelSimeoneNo ratings yet

- Brazilian Composer Mozart Camargo Guarnieri BiographyDocument3 pagesBrazilian Composer Mozart Camargo Guarnieri Biographycarlos guastavino100% (1)

- 21st Century Oboe PDFDocument5 pages21st Century Oboe PDFFernandoNo ratings yet

- Viola String Colour Chart ComparisonDocument5 pagesViola String Colour Chart ComparisonJNo ratings yet

- String Diplomas Repertoire ListDocument20 pagesString Diplomas Repertoire ListsamNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Hungarian Rock Written by Gyorgy LigetiDocument12 pagesAn Analysis of Hungarian Rock Written by Gyorgy LigetiSara Ramos ContiosoNo ratings yet

- Multiphonics and The OboeDocument19 pagesMultiphonics and The OboeDimitry StavrianidiNo ratings yet

- Book 3Document22 pagesBook 3jimmmusicNo ratings yet

- 2018 Summer BlossomingDocument13 pages2018 Summer Blossomingnelly.couderq.harpistNo ratings yet

- Denisov - Sonata For 2 ViolinsDocument24 pagesDenisov - Sonata For 2 ViolinsRichard BakerNo ratings yet

- Baroque Era - Interactive QuizDocument14 pagesBaroque Era - Interactive QuizClarence TanNo ratings yet

- Rehearsal LetterDocument4 pagesRehearsal LetterM. KorhonenNo ratings yet

- British Forum For EthnomusicologyDocument5 pagesBritish Forum For EthnomusicologyerbariumNo ratings yet

- Frank de Bruine, OboeDocument13 pagesFrank de Bruine, OboeHåkon HallenbergNo ratings yet

- Derus. .Sorabji Studies (2003)Document3 pagesDerus. .Sorabji Studies (2003)AlexNo ratings yet

- Chamber Music in Historic Sites 2010-11 Season BrochureDocument17 pagesChamber Music in Historic Sites 2010-11 Season BrochureDaCameraSocietyNo ratings yet

- Consecutio Temporum (For Violoncello Solo)Document20 pagesConsecutio Temporum (For Violoncello Solo)Tolga YayalarNo ratings yet

- Torroba Piece PresentationDocument2 pagesTorroba Piece PresentationNick FallerNo ratings yet

- Ralph Vaughan WilliamsDocument3 pagesRalph Vaughan WilliamsDavid RubioNo ratings yet

- PMLP59201-Vivaldi Concerto 2 Oboes RV 535Document7 pagesPMLP59201-Vivaldi Concerto 2 Oboes RV 535dngrxNo ratings yet

- LOCKSPEISER - The Berlioz-Strauss Treatise On InstrumentationDocument9 pagesLOCKSPEISER - The Berlioz-Strauss Treatise On InstrumentationtbiancolinoNo ratings yet

- Baroquesuite 1Document4 pagesBaroquesuite 1sidneyvasiliNo ratings yet

- Dmitri Shostakovich - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument19 pagesDmitri Shostakovich - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaTarlan FisherNo ratings yet

- Bach Goldberg Variations AriaDocument1 pageBach Goldberg Variations AriaNacho TauletNo ratings yet

- History of Collection and Recording of Samples of Uzbek Music FolkloreDocument4 pagesHistory of Collection and Recording of Samples of Uzbek Music FolkloreEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Opera in Portugal in The Eighteenth CenturyDocument23 pagesOpera in Portugal in The Eighteenth CenturyetazevedoNo ratings yet

- Theory Historical PerformanceDocument27 pagesTheory Historical PerformanceMariachi VeracruzNo ratings yet

- Sergei Prokofiev's Violin Concerto No. 1 in D MajorDocument3 pagesSergei Prokofiev's Violin Concerto No. 1 in D MajorethanNo ratings yet

- Soal For Music Analysis: A Study Case With: Berio'S Sequenza IvDocument5 pagesSoal For Music Analysis: A Study Case With: Berio'S Sequenza IvOliver SchenkNo ratings yet

- Willem Pijper's Legacy as a Dutch Composer and PedagogueDocument21 pagesWillem Pijper's Legacy as a Dutch Composer and Pedagoguegroovy13No ratings yet

- Lengnick Catalogue PDFDocument31 pagesLengnick Catalogue PDFGinger BowlesNo ratings yet

- Landscapes: Scarlatti Schubert Albéniz Mompou Andrew TysonDocument16 pagesLandscapes: Scarlatti Schubert Albéniz Mompou Andrew TysonPaul DeleuzeNo ratings yet

- Duda, Cynthia M. - Influences On The Performance of Vivaldi's Bassoon Concertos at The Ospedale Della PietàDocument79 pagesDuda, Cynthia M. - Influences On The Performance of Vivaldi's Bassoon Concertos at The Ospedale Della PietàmassiminoNo ratings yet

- Columbus Symphony Viola AuditionDocument21 pagesColumbus Symphony Viola Auditionvqv90416No ratings yet

- Variations on the Theme Galina Ustvolskaya: The Last Composer of the Passing EraFrom EverandVariations on the Theme Galina Ustvolskaya: The Last Composer of the Passing EraNo ratings yet

- DalcrozeidentityDocument36 pagesDalcrozeidentityFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Toucher Mix 2 Berlin Kammermusik.m4a: Download PDFDocument2 pagesToucher Mix 2 Berlin Kammermusik.m4a: Download PDFFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Mark Alan Schulz Film ScoresDocument4 pagesMark Alan Schulz Film ScoresFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Boulez AnalysisDocument30 pagesBoulez AnalysisFred Fredericks100% (2)

- Elementary Orchestration: Course Syllabus - Spring 2010Document2 pagesElementary Orchestration: Course Syllabus - Spring 2010Fred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Dalcroze School of The RockiesDocument2 pagesDalcroze School of The RockiesFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Ks 3 Progression and Programme of Study at A GlanceDocument3 pagesKs 3 Progression and Programme of Study at A GlanceFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Paradox in Indian Classical MusicDocument7 pagesParadox in Indian Classical MusicFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Seitz - Dalcroze, The Body, Movement and MusicalityDocument18 pagesSeitz - Dalcroze, The Body, Movement and MusicalityFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 343 8142 PDFDocument173 pages10 1 1 343 8142 PDFFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Dalcroze Eurhythmics Music Education ApproachDocument1 pageDalcroze Eurhythmics Music Education ApproachFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- L'I D T D I: Dentité Alcrozienne HE Alcroze DentityDocument36 pagesL'I D T D I: Dentité Alcrozienne HE Alcroze DentityFred Fredericks100% (1)

- How To Borrow From Folk SongsDocument6 pagesHow To Borrow From Folk SongsFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Visualizing Musical DynamicsDocument134 pagesVisualizing Musical DynamicsFred Fredericks100% (1)

- Nerd vs. Geek: The Development of A ThemeDocument9 pagesNerd vs. Geek: The Development of A ThemeFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Pastiche and PostmodernismDocument22 pagesPastiche and PostmodernismFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Dalcroze Eurhythmics in The Context of Copland's Appalachian SpringDocument16 pagesDalcroze Eurhythmics in The Context of Copland's Appalachian SpringFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Mahler's BeethovenDocument13 pagesMahler's BeethovenFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Musical Composition: Using 12-Tone Chords With Minimum TensionDocument7 pagesMusical Composition: Using 12-Tone Chords With Minimum TensionFábio LopesNo ratings yet

- Towards Modeling Texture in Symbolic DataDocument6 pagesTowards Modeling Texture in Symbolic DataFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- The Complete Guide For EWQLSODocument109 pagesThe Complete Guide For EWQLSOSkribahNo ratings yet

- Melodic Grouping in Music Information Retrieval: New Methods and ApplicationsDocument26 pagesMelodic Grouping in Music Information Retrieval: New Methods and ApplicationsFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Tempo in Mahler As Recollected by Natalie Bauer-LechnerDocument4 pagesTempo in Mahler As Recollected by Natalie Bauer-LechnerFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Portrait GlobokarDocument1 pagePortrait GlobokarFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Degazio Schillinger ArticleDocument9 pagesDegazio Schillinger ArticleBruno DegazioNo ratings yet

- Music Theory - AdvancedDocument33 pagesMusic Theory - Advancedkiafarhadi100% (19)

- Mahler ResearchDocument6 pagesMahler ResearchFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Creating The Step Editor's Missing Expression Lane in Logic Pro XDocument5 pagesCreating The Step Editor's Missing Expression Lane in Logic Pro XFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Dissertation 2Document45 pagesDissertation 2Adham FahmyNo ratings yet

- Cerulean: (Through The Sky)Document1 pageCerulean: (Through The Sky)Meyshon José De León bellorinNo ratings yet

- The Weekender 05-30-2012Document72 pagesThe Weekender 05-30-2012The Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- Differentiated Instruction For Advanced Students With AnswerDocument64 pagesDifferentiated Instruction For Advanced Students With AnswermishhuanaNo ratings yet

- MWR Narrative RevisedDocument5 pagesMWR Narrative RevisedpeterhjeonNo ratings yet

- The Good Shepherd Ministry Noraville Subd., Tugatog, Orani, BataanDocument2 pagesThe Good Shepherd Ministry Noraville Subd., Tugatog, Orani, BataanRonnel Dela Rosa LacsonNo ratings yet

- Richard Wagner Musical GeniusDocument104 pagesRichard Wagner Musical Geniuslucijaluja100% (1)

- Essay On Lohri: Why Is Lohri Celebrated?Document3 pagesEssay On Lohri: Why Is Lohri Celebrated?Rits MonteNo ratings yet

- Aristo Tile As A PoetDocument264 pagesAristo Tile As A Poetd.dr8408No ratings yet

- Control LISTA Remember21!04!10Document60 pagesControl LISTA Remember21!04!10Anna KochNo ratings yet

- Michael Brecker Archive MaterialsDocument6 pagesMichael Brecker Archive Materialsvvvvv12345No ratings yet

- Reimagining the synthesizer for an acoustic settingDocument102 pagesReimagining the synthesizer for an acoustic settingDenny George100% (1)

- Production Staff Positions in TheaterDocument19 pagesProduction Staff Positions in TheaterNor Azman MohammedNo ratings yet

- Lagu Lain2Document2 pagesLagu Lain2nurulhilwadianaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan: Teacher(s) : Mr. Alex Meek Grade Level: College Date Taught: 2/15/18 Lesson Title: Lesson 8 Subject: U BandDocument2 pagesLesson Plan: Teacher(s) : Mr. Alex Meek Grade Level: College Date Taught: 2/15/18 Lesson Title: Lesson 8 Subject: U Bandapi-438868797No ratings yet

- Eyes Open 3 Test 1 Music FestivalDocument7 pagesEyes Open 3 Test 1 Music FestivalAbdelghani QouhafaNo ratings yet

- Facets of Indian Culture OptDocument281 pagesFacets of Indian Culture OptHeather CarterNo ratings yet

- Grammar GuideDocument66 pagesGrammar GuidebeticabestNo ratings yet

- Ôn Tập Unit 4 A. Phonetics and Speaking: Chọn từ có phần gạch chân được phát âm khácDocument8 pagesÔn Tập Unit 4 A. Phonetics and Speaking: Chọn từ có phần gạch chân được phát âm khácPhương Anh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Week 7 MusicDocument97 pagesWeek 7 MusicShena RodajeNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes On DramaDocument2 pagesLecture Notes On DramaAnthony Miguel Rafanan100% (1)

- All Young The DudesDocument2 pagesAll Young The DudesRafael PereiraNo ratings yet

- Expo - Oral Presentation - With Excerpts - Isabella SpinelliDocument9 pagesExpo - Oral Presentation - With Excerpts - Isabella SpinellinurjNo ratings yet

- Bach 6 Cello Suites Without Slurs Yokoyama 2013 NotesDocument15 pagesBach 6 Cello Suites Without Slurs Yokoyama 2013 NotesJorge Díaz Violista100% (3)

- Interval Cycle - WikipediaDocument3 pagesInterval Cycle - WikipediaAla2 PugaciovaNo ratings yet

- Neon Genesis Evangelion - Fly Me To The MoonDocument7 pagesNeon Genesis Evangelion - Fly Me To The MoonPrimo100% (1)

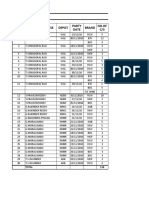

- N Tel Nov'10 Party Order DetailsDocument5 pagesN Tel Nov'10 Party Order DetailsMohammad AleemNo ratings yet

- Sligo Jazz Summer School and Festival 2022Document24 pagesSligo Jazz Summer School and Festival 2022The Journal of MusicNo ratings yet

- CONGADocument1 pageCONGAMauricio FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Welcome To Creepy CastleDocument4 pagesWelcome To Creepy CastleTim ReichertNo ratings yet